Abstract

Calcium (Ca2+) plays a central role in mediating both contractile function and hypertrophic signaling in ventricular cardiomyocytes. L-type Ca2+ channels trigger release of Ca2+ from ryanodine receptors for cellular contraction, whereas signaling downstream of G-protein-coupled receptors stimulates Ca2+ release via inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs), engaging hypertrophic signaling pathways. Modulation of the amplitude, duration, and duty cycle of the cytosolic Ca2+ contraction signal and spatial localization have all been proposed to encode this hypertrophic signal. Given current knowledge of IP3Rs, we develop a model describing the effect of functional interaction (cross talk) between ryanodine receptor and IP3R channels on the Ca2+ transient and examine the sensitivity of the Ca2+ transient shape to properties of IP3R activation. A key result of our study is that IP3R activation increases Ca2+ transient duration for a broad range of IP3R properties, but the effect of IP3R activation on Ca2+ transient amplitude is dependent on IP3 concentration. Furthermore we demonstrate that IP3-mediated Ca2+ release in the cytosol increases the duty cycle of the Ca2+ transient, the fraction of the cycle for which [Ca2+] is elevated, across a broad range of parameter values and IP3 concentrations. When coupled to a model of downstream transcription factor (NFAT) activation, we demonstrate that there is a high correspondence between the Ca2+ transient duty cycle and the proportion of activated NFAT in the nucleus. These findings suggest increased cytosolic Ca2+ duty cycle as a plausible mechanism for IP3-dependent hypertrophic signaling via Ca2+-sensitive transcription factors such as NFAT in ventricular cardiomyocytes.

Significance

Many studies have identified a role for inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R)-mediated Ca2+ signaling in cardiac hypertrophy; however, the signaling mechanism remains unclear. Here we present a mathematical model of functional interactions between ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and IP3Rs, and show that IP3-mediated Ca2+ release can increase the Ca2+ duty cycle, which has been shown experimentally to lead to NFAT activation and hypertrophic signaling. Through a parameter sensitivity analysis, we demonstrate that the duty cycle increases with IP3 over a broad parameter regime, indicating that this mechanism is robust, and furthermore we show that increasing Ca2+ duty cycle raises nuclear NFAT activation. These findings suggest a plausible mechanism for IP3R-dependent hypertrophic signaling in cardiomyocytes.

Introduction

Calcium is a universal second messenger that plays a role in controlling many cellular processes across a wide variety of cell types, ranging from fertilization, cell contraction, and cell growth to cell death (1,2). Precisely how Ca2+ fulfills each of these roles while also ensuring signal specificity remains unclear in many cases. Ca2+ can be used to transmit signals in a variety of ways. Signal localization and amplitude and frequency modulation have been widely explored (3, 4, 5); however, mechanisms for information encoding in the cumulative signal (i.e., area under the curve, proportional-integral-derivative controller, or duty cycle) have also been proposed (6, 7, 8). Determining which method of information encoding is relevant to a specific signaling pathway requires determining what type of signal encoding the system is capable of and whether the downstream effector of the signal is capable of temporal signal integration, high- or low-pass filtering, or threshold filtering.

In cardiac myocytes, discrete encoding of multiple Ca2+-mediated signals is particularly pertinent because of the essential and continuous role Ca2+ plays in excitation-contraction coupling (ECC). Of particular significance is the involvement of Ca2+ in hypertrophic growth signaling. How Ca2+ can communicate a signal in the hypertrophic signaling pathway concurrent with the cytosolic Ca2+ fluxes that drive cardiac muscle contraction is still largely unresolved (9,10). Understanding this mechanism is important because pathological hypertrophic remodeling is a precursor of heart failure and a common final pathway of cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension and coronary disease (11, 12, 13).

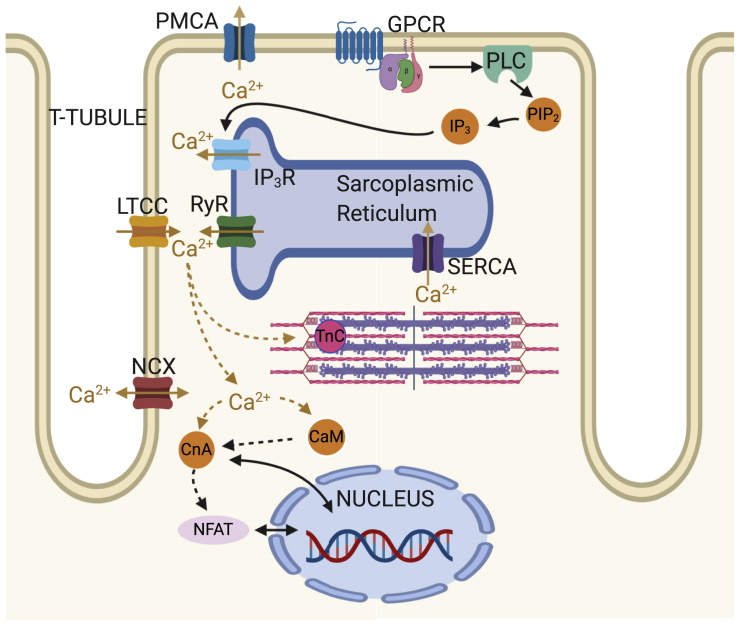

During each heartbeat, on depolarization of the membrane Ca2+ enters the cell via L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCCs), triggering larger Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) via ryanodine receptors (RyRs), which then induces contraction. The activation of Ca2+ release via RyRs by the Ca2+ arising via LTCCs is known as calcium-induced calcium release and results in a 10-fold increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (relative to resting Ca2+ concentration of ∼100 nM). Sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pumps (SERCA) and other Ca2+ sequestration mechanisms subsequently withdraw the released Ca2+ back into the SR and out of the cytosol (14,15), reverting the cell to its relaxed state. Ca2+ also plays a central role in hypertrophic signaling. Hypertrophic stimuli such as endothelin-1 (ET-1) bind to G-protein-coupled receptors at the cell membrane to stimulate generation of the intracellular signaling molecule inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3). After IP3 binds to and activates its cognate receptor, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs), on the SR and nuclear envelope, Ca2+ is released into the cytosol and nucleus, respectively (see Fig. 1; (16,17)). This Ca2+ signal arising from IP3Rs has been shown in multiple mammalian species to produce a distinct Ca2+ signal that through activation of pro-hypertrophic pathways, including those involving nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), induces hypertrophy within cardiomyocytes (16,18,19).

Figure 1.

Schematic showing key Ca2+signaling pathways in the cardiomyocyte. ECC processes include ryanodine receptors (RyRs), L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCCs), SERCA, sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX), sarcolemmal calcium pump (PMCA), and troponin C (TnC). Growth-related IP3-CnA/NFAT signaling processes include inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs), G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), phospholipase C (PLC), phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), calmodulin (CaM), calcineurin (CnA), and nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT). To see this figure in color, go online.

In healthy adult rat ventricular myocytes (ARVMs), various effects of IP3 on global Ca2+ transients associated with ECC have been described, summarized in Table 1. Although application of G-protein-coupled receptor agonists that stimulate IP3 generation produces robust effects on ECC-associated IP3 transients and contraction, the direct contribution of IP3 to these actions varies between studies (17,20, 21, 22, 23, 24). For example, in rabbits the effect of ET-1 on Ca2+ transient amplitude is sensitive to the IP3R inhibitor 2-APB (22), whereas in healthy rats, IP3R inhibition with 2-APB was without effect (25). In mice, 2-APB abrogated an increase in ECC-associated Ca2+ transients brought about by AngII (24). Responses have also been variable when IP3 was directly applied to cardiac myocytes. In healthy rats, IP3 produced no or a modest effect on Ca2+ transient amplitude (17,21), whereas in rabbits (22), a more substantial effect was observed. These differences in the effect of IP3 have been ascribed in part to the greater dependence of rat myocytes on SR Ca2+ release to the Ca2+ transient than rabbit myocytes (22). Notably, both ET-1 and IP3 elicit arrhythmogenic effects whereby they promote the generation of spontaneous calcium transients, manifest as a prolonged Ca2+ transient with additional peaks, and increase the frequency of Ca2+ sparks (17,18,21,22). A more profound role for IP3 signaling is observed in hypertrophic ventricular myocytes, with ECC-associated Ca2+ transients of greater amplitude reported. Underlying these effects, IP3R expression is elevated in hypertrophy (26). Hence, a question remains as to what independent effect IP3R activation has on the cytosolic Ca2+ transient in healthy ventricular cardiac myocytes.

Table 1.

Summary of Experimentally Observed Changes to the Ca2+ Transient in Normal Healthy Ventricular Myocytes in Rat and Other Species after Addition of IP3 and ET-1

| Cell State | IP3 | ET-1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | Amplitude: | r▲(21) r♦(17) | r▲(21) r♦(16) r▲(17) |

| Duration: | – | – | |

| Basal Ca2+: | r♦(17) | r♦(17) | |

| SCTs: | r▲(21) r▲(17) | r▲(21) r▲(17) | |

| Other species | Amplitude: | m▲(20) m♦(73) | h▲(20) m▲(20) |

| Duration: | – | – | |

| Basal Ca2+: | m▲(73) | m▲(20), b▲(22) | |

| SCTs: | – | h▲(20) m▲(20) |

SCT, spontaneous Ca2+ transient. ▲ indicates an increase, ▼ a decrease, and ♦ indicates no significant change reported; r indicates rat, b indicates rabbit, h indicates human, and m indicates mouse; dashes indicate no data found. The model developed in this work is primarily parameterized with rat data.

The individual behavior of IP3R channels and their dependence on Ca2+, IP3, and ATP in cardiac and other cell types has been explored in a number of studies (27, 28, 29, 30). These studies have formed the basis of several computational models of IP3R type I isoforms (29,31,32) fitted to stochastic single-channel data (33). However, properties of IP3R channel activity within the cardiomyocyte, such as gating state transition rates and their dependency on IP3 and Ca2+, have not been directly measured. In this study, we have taken the experimental studies on rat ventricular cardiomyocytes as a reference point for the observed effects of IP3R activation on cellular Ca2+ dynamics and extended a well-established model of beat-to-beat cytosolic Ca2+ transients in rat cardiac cells (14,34) to include a model of type II IP3R (32) channels. This deterministic, compartmental model of ECC enables us to investigate biophysically plausible mechanisms by which IP3R activation could affect Ca2+ dynamics at the whole-cell scale while avoiding the computational complexity associated with detailed stochastic and spatial modeling. Specifically, it enables us to explore the parameter ranges of IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release that modify the global cytosolic Ca2+ transient to encode information for hypertrophic signaling to the nucleus.

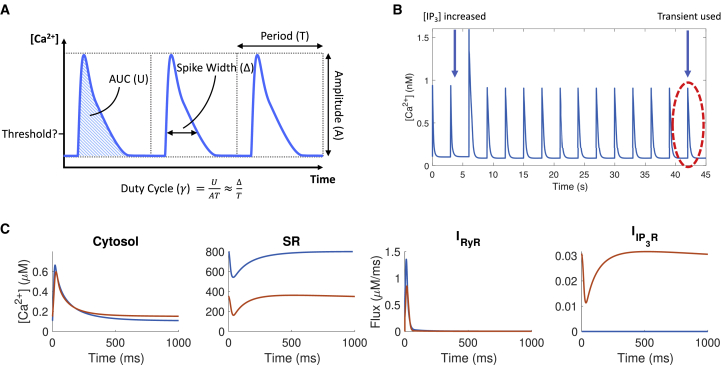

A number of transcription factors transduce changes in Ca2+ to activate hypertrophic gene transcription. Of particular note is NFAT. There are five known NFAT isoforms expressed in mammals; four of these are found in cardiac cells (19,35). To initiate hypertrophic remodeling, the hypertrophic Ca2+ signal, in conjunction with calmodulin (CaM) and calcineurin (CnA), leads to dephosphorylation of cytosolic NFAT. Upon dephosphorylation, NFAT translocates to the nucleus, where, in coordination with other proteins, it activates expression of genes responsible for hypertrophy (36). Several studies have focused on characterizing the Ca2+ dynamics necessary to activate NFAT and initiate hypertrophy (8,19,37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42) and have shown NFAT to be a Ca2+ signal integrator (37). Furthermore, a recent study by Hannanta-anan and Chow (8) used direct optogenetic control of cytosolic Ca2+ transients in HeLa cells to demonstrate that the transcriptional activity of NFAT4 (also known as NFATc3), a necessary NFAT isoform in the hypertrophic pathway (35), can be upregulated by increasing the residence time of Ca2+ in the cytosol within each oscillation. The increased residence time of Ca2+, referred to as the “duty cycle,” is the ratio between the area under the Ca2+ transient curve divided by the maximal possible area, as calculated by the product of transient amplitude and period (see Fig. 2 A). The Ca2+ duty cycle is therefore distinct from the average Ca2+ concentration. Hannanta-anan and Chow (8) showed that increasing the duty cycle had a proportionally greater effect on NFAT transcriptional activity than changing either the frequency or amplitude of the cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations. This suggests an increased Ca2+ duty cycle as a possible mechanism by which Ca2+ release through IP3R channels can affect hypertrophic signaling.

Figure 2.

(A) The duty cycle, a function of area under the curve, amplitude, and period, for the cytosolic Ca2+ transient. (B) An example of Ca2+ transients generated by the model is shown. (C) Ca2+ concentration in cytosol and SR, RyR flux, and IP3R flux in the model with elevated IP3 (red) and without IP3 (blue) are shown. Here, IP3R parameters used are taken from (32), with maximal IP3R flux kf = 0.003 μm3 ms−1. To see this figure in color, go online.

Here, using a mathematical model of beat-to-beat cytosolic Ca2+ transients in rat ventricular myocytes, coupled to IP3R channel Ca2+ release, we show that IP3R activation in the cytosol can increase the duty cycle of the cytosolic Ca2+ transient. We establish model feasibility through parameter sensitivity analysis, which shows that this behavior does not depend sensitively on model parameter values. Furthermore, we identify conditions necessary for IP3R channel activation to alter Ca2+ transient amplitude, width, basal Ca2+, and duty cycle, as identified in different experimental studies, and compare model simulations to published experimental data summarized in Table 1. Finally, we couple simulations of cytosolic Ca2+ dynamics to a model of downstream CaM/CnA/NFAT activation and show that the duty cycle of the Ca2+ transient highly correlates with the activated nuclear NFAT (the proportion of NFAT that is dephosphorylated and translocated to the nucleus). These findings suggest IP3R activity can increase the cytosolic Ca2+ duty cycle, thus providing a mechanism for IP3-dependent activation of NFAT for hypertrophic signaling in the cardiomyocyte.

Methods

We developed a computational model of RyR- and IP3R-mediated Ca2+ fluxes in the adult rat ventricular myocyte. Model simulations were performed using the ode15s ODE solver from MATLAB 2017b (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) with relative and absolute tolerances 1 × 10−3 and 1 × 10−6, respectively. The model equations were simulated at 1 Hz, the original pacing frequency of the Hinch et al. (14) model, and at 0.3 Hz because it is another common pacing frequency in experimental studies of IP3 and Ca2+ in cardiomyocytes (17,21). The model was paced until the normalized root mean-square deviation between each subsequent beat was below 1 × 10−3, and all but the last oscillation were discarded to eliminate transient behaviors (see Fig. 2 B). Initial conditions were set to the basal Ca2+ level of the model at dynamic equilibrium with inactive IP3R channels, determined after running the base model until the normalized root mean-square deviation was also below 1 × 10−3.

Model equations

The compartmental model of rat left ventricular cardiac myocyte Ca2+ dynamics is based on the Hinch et al. (14) model of ECC, with the addition of IP3R Ca2+ release modeled using the Siekmann-Cao-Sneyd model (32). The Hinch model is an established whole-cell model of rat cardiac Ca2+ dynamics that describes the flux through the major Ca2+ channels and pumps on the cell and SR membranes and the effects of applying a voltage across the cell membrane. The parameters for the Hinch component of our model were maintained from the original, except for those of the driving voltage. This was shortened to better approximate the rat action potential (43) (see Fig. S1). The Ca2+ in the cytosol is governed by the following ODE:

| (1) |

| (2) |

A small Ca2+ flux through the LTCCs, ICaL, activates RyR channels to release Ca2+ from the SR into the cytosol at a rate of IRyR. Ca2+ is resequestered into the SR by SERCA at a rate ISERCA. βfluo is the rapid buffer coefficient (44) for the fluorescent dye in the cytosol, and βCaM is the rapid buffer coefficient for calmodulin in the cytosol. Iother includes Ca2+ fluxes such as exchange with the extracellular environment through the sodium-calcium exchanger INCX, sarcolemmal Ca2+-ATPase IPMCA, and the background leak current ICaB, as well as the SR leak current ISRl and buffering on troponin C ITnC. These fluxes are defined in the Supporting Materials and Methods.

When the simulation is run with IP3 present, there is additionally a flux through the IP3Rs:

| (3) |

Here, Vmyo is the volume of the cell. kf is the maximal total flux through each IP3R channel; this was chosen to be 0.45 μm3 ms−1 unless otherwise stated to create a measurable effect on IP3R channel activation while maintaining plausible total flux. is the number of IP3R channels in the cell; this was set to 1/50th of the number of RyR channels (45). We studied the effect of varying kf on IP3-induced changes to the cytosolic Ca2+ transient in normal cardiomyocytes. Evidently, varying and varying kf have the same effect on simulated calcium dynamics. Although is known to increase significantly in disease conditions, we have not emphasized it in this study because of our focus on normal cardiomyocytes. [Ca2+]cyt and [Ca2+]SR are the Ca2+ concentrations in the cytosol and SR, respectively.

is the [Ca2+]- and [IP3]-dependent open probability of the IP3R channels and is determined using the Siekmann-Cao-Sneyd model (31,32,46), which has a built-in delay in response to changing Ca2+ concentration, along with several parameters governing channel activation and inactivation. This model describes as

| (4) |

where kβ is a transition term derived from single-channel Siekmann et al. (46) and β describes the rate of activation and α the rate of inactivation:

| (5) |

| (6) |

where h is time dependent and B, m, and h and h∞ describe the dependence on IP3, the dependence on Ca2+, and the Ca2+-dependent delay in IP3R gating, respectively. Expressions for these variables are as follows:

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

Here, Kc and Kh are parameters that determine the Ca2+-dependence of IP3R channel open probability, whereas Kt and tmax are parameters that affect the delay in IP3R response to cytosolic changes. Kt determines the influence of [Ca2+] on the delay, whereas tmax is a temporal scaling factor.

We note that the SR leak flux, ISRl, is unchanged from the Hinch model and would include the effects of diastolic IP3R Ca2+ release at normal IP3 levels because that model did not explicitly include IP3R. However, in the presence of IP3, IP3R Ca2+ flux during diastole is several orders of magnitude greater than ISRl, which is largely dependent on [Ca2+]SR, and hence, any discrepancy caused by this will have a negligible effect on overall Ca2+ dynamics within the cell (see also Fig. S4).

Several experimental studies have investigated IP3R activity across a range of Ca2+ concentrations with 1 μM IP3 (27,47). These studies suggest that IP3R channels would be open, with almost constant over the full range of cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations experienced during ECC in the cardiomyocyte. An IP3R-facilitated SR-Ca2+ leak has been reported to amplify systolic concentrations (48,49), as seen in most published experiments of IP3-enhanced Ca2+ transients tabulated in Table 1. Through parameter sensitivity analysis of this model, we show that to be consistent with these observations, must be significantly smaller at resting Ca2+ concentrations than at higher concentrations.

Coupling cytosolic Ca2+ and NFAT activation

We coupled the calcium model to the NFAT model developed by Cooling et al. (50), which determines the proportion of total cellular NFAT that is dephosphorylated and translocated to the nucleus for a given cytosolic Ca2+ signal. In this study, we have used the model parameters estimated from the data in Tomida et al. (37), who measured activation of NFAT4 in BHK cells. Full details of the Cooling et al. (50) model are given in the Supporting Materials and Methods.

Results

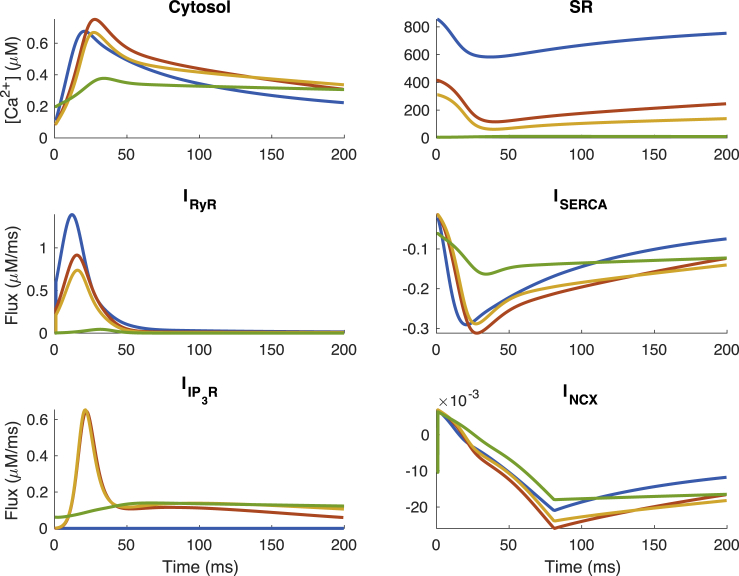

An example of the model output when run with the original IP3R channel parameter values determined by Sneyd et al. (32) for type I IP3R channels is shown in Fig. 2 C. Measurements of the properties of IP3R channel activity and their dependence on Ca2+ within cardiomyocytes are sparse in the literature. Therefore, we performed a parameter sensitivity analysis by running model simulations over a variety of parameter ranges to explore the dependence of features of the cytosolic calcium transient to IP3R channel parameters.

Parameter sensitivity analysis

We conducted a parameter sensitivity analysis to determine the critical parameters related to IP3R activation that affect the shape of beat-to-beat cytosolic Ca2+ transients. We used the Jansen method (51) as described in Saltelli et al. (52) (and summarized in the Supporting Materials and Methods) to calculate the “main effect” and “total effect” coefficients of each of the parameters associated with IP3R channel gating in relation to changes in transient amplitude, full duration at half maximum (FDHM), diastolic Ca2+, and duty cycle (see Table 2). Saltelli et al. (52) describe the main effect coefficient as “the expected reduction in variance that would be obtained if [the parameter] could be fixed” and the total effect coefficient as “the expected variance that would be left if all factors but [the parameter] could be fixed,” both normalized by the total variance. Both coefficients are included here to provide a complete picture of the impact of each parameter. Simulation parameter values were generated using the MATLAB (The MathWorks) sobolset function with leap 1 × 103 and skip 1 × 102.

Table 2.

Main and Total Effects of the IP3R Gating Parameters on Ca2+ Transient Amplitude, Duration, Diastolic Ca2+, and Duty Cycle

| Main Effect Coefficients | [IP3] | tmax | Kc | Kh | Kt | kf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude | 027a | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.19a | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Duration (FDHM) | 0.17a | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.12a | 0.00 | 0.50a |

| Diastolic Ca2+ | 0.44a | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Duty cycle | 0.23a | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.16a | 0.00 | 0.33a |

| Total Effect Coefficients | [IP3] | tmax | Kc | Kh | Kt | kf |

| Amplitude | 0.63a | 0.04 | 0.43a | 0.46a | 0.02 | 0.13a |

| Duration (FDHM) | 0.33a | 0.00 | 0.19a | 0.19a | 0.00 | 0.54a |

| Diastolic Ca2+ | 0.79a | 0.00 | 0.45a | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.18a |

| Duty cycle | 0.45a | 0.00 | 0.25a | 0.24a | 0.00 | 0.38a |

Duration measured in FDHM.

Significant values.

Variance-based parameter sensitivity analysis

Table 2 shows that the delay parameters tmax and Kt do not have a large effect on the cytosolic Ca2+ transient. Although they are necessary to describe the effect of IP3R-dominated Ca2 dynamics (32), they contribute only a small amount to the variance. Therefore, we decided to fix these parameters in our simulations.

As expected, the coefficients show that cardiac cell Ca2+ dynamics during ECC are most highly sensitive to IP3 concentration ([IP3]) and the maximal flux through each IP3R (kf). The maximal flux kf has little effect on transient amplitude but large influence on duration and duty cycle, whereas [IP3] has the greatest effect on the change in amplitude and diastolic Ca2+ concentration.

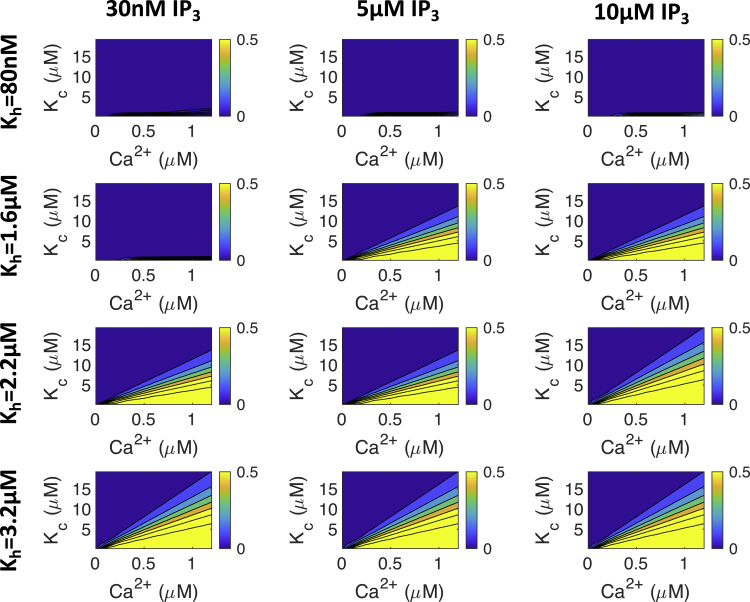

The gating parameters Kc and Kh also influence the cytosolic Ca2+ transient. Kh affects the [Ca2+] at which IP3R channels are inhibited, and Kc affects the [Ca2+] at which IP3R channels open. We illustrate how these two parameters affect IP3R open probability, , in Fig. 3. Fig. 3 also shows how [IP3] affects the relationship between Kc, Kh, [Ca2+], and . It can be seen that with Kh = 80 nM, will be close to zero regardless of the values of Ca2+ or [IP3] or Kc. At Kh = 1.6 μM and [IP3] ≥ 5 μM, dependence on Kc and Ca2+ becomes apparent. Finally, at Kh = 3.2 μM, is still dependent on Kc- and Ca2+-values, but [IP3] does not change significantly.

Figure 3.

The effect of [Ca2+], [IP3], Kc, and Kh on in the Siekmann-Cao-Sneyd IP3R model (31,32,46). The colored bars on the side of each plot show the proportion of IP3R channels that will open for each set of parameters at steady state. Note that IP3Rs do not open at physiological Ca2+ concentrations when Kh is low (i.e., 80 nM or less). In subsequent simulations, we used the value Kh = 2.2 μM unless otherwise stated. To see this figure in color, go online.

From this analysis, we determine that for IP3R channels to be active during ECC, Kh must be sufficiently high that IP3Rs are not inhibited at diastolic [Ca2+]. Conversely, Kc must be low enough that IP3R channels are active at Ca2+ concentrations below the systolic Ca2+ peak. Therefore, in the remainder of this study, we fix Kh at 2.2 μM: high enough to fulfill this condition but low enough that IP3R channels are still affected by [IP3]. We report simulation results only within the range of Kc that exhibits experimentally plausible Ca2+ transient properties.

With the plausible range of Kh and Kc established, we next show the effect of Kc, kf, and [IP3] on the ECC transient.

IP3 concentration and IP3R opening behavior have the greatest impact on the Ca2+ transient

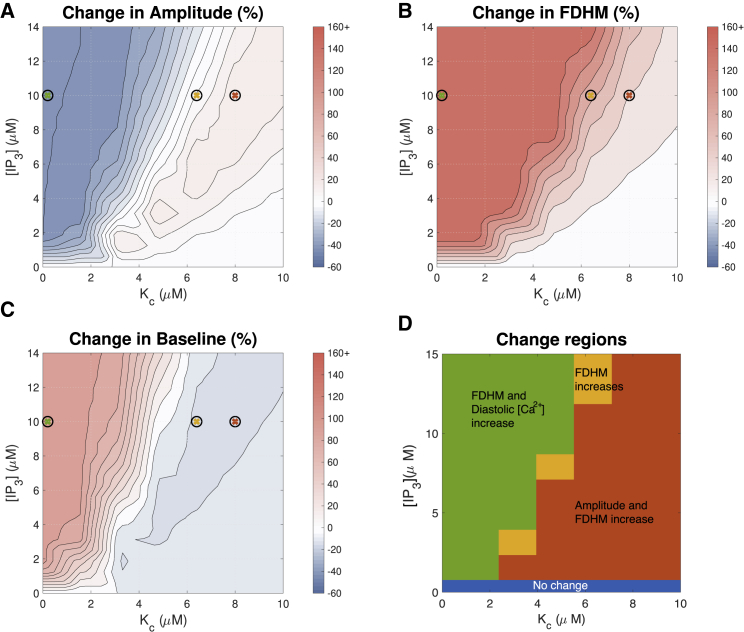

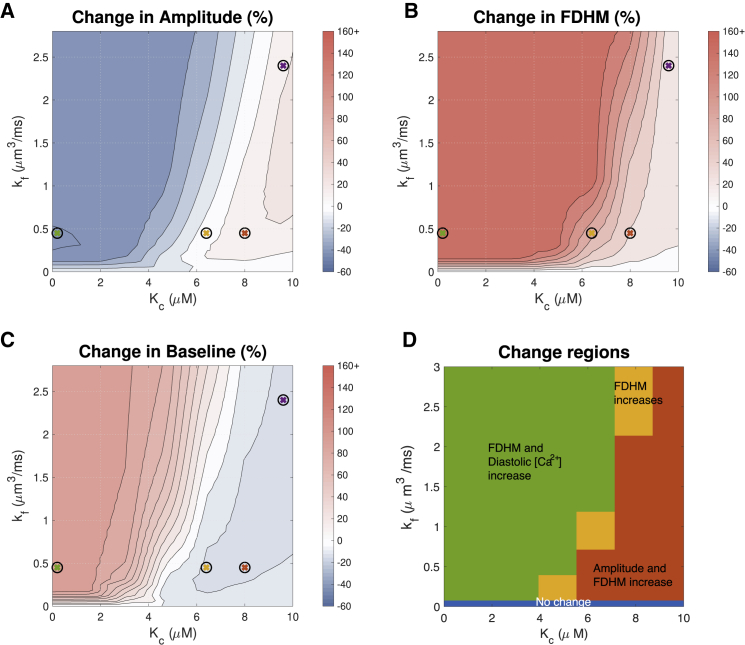

As summarized in Table 1, different experimental studies suggest different effects of IP3R activation on the ECC cytosolic Ca2+ transient. Fig. 4, A–C show quantitative predictions of how much Ca2+ transient properties could be affected by IP3R activation across a range of [IP3]- and Ca2+-dependent IP3R gating parameter Kc-values. kf was fixed at 0.45 μm3 ms−1, and Kh was fixed at 2.2 μM.

Figure 4.

Effect of IP3 concentration and the parameter Kc on the Ca2+ transient with pacing frequency 1 Hz. These two parameters, along with maximal IP3R flux kf, have the greatest impact when considering the effect of IP3R activation on the Ca2+ transient. To better resolve the range in which FDHM changes, all FDHM increases of 45% and over are shown in the same color. See Fig. 5 for simulated transients at parameters indicated by crosses. We note that for ease of comparison between figures, in this and in subsequent figures, the maximal increase from baseline is cropped at 160%. Changes greater than this threshold are shown in the same color. To see this figure in color, go online.

The red region in Fig. 4 A corresponds to IP3R activation parameters that produce the greatest increase in Ca2+ amplitude. Noteworthy is that the red region depicts moderate changes in amplitude of ∼15%. This region corresponds to Kc-values greater than 4 μM and [IP3] greater than 2 μM. With Kh set at 2.2 μM, this corresponds to the middle and far-right plots of in Fig. 3. The middle subfigure shows that with Kc greater than 4 μM, IP3R channels would open only at Ca2+ concentrations greater than the diastolic concentration of ∼0.1 μM. The plot also shows that IP3Rs would remain active at Ca2+ greater than the systolic peak concentration of ∼1 μM (53). Fig. 4 B further indicates that the increase in peak amplitude is accompanied by an increase in transient duration (FDHM). However, this change may be small, particularly at IP3 concentrations lower than 1 μM. In Fig. 4 C, it can be seen that the diastolic Ca2+ concentration decreases moderately (∼10%) in the parameter range in which the amplitude is maximized (Fig. 4 A).

Fig. 4 B shows that FDHM of the Ca2+ transient increases whenever IP3Rs are active. This increase is greater with greater concentrations of IP3 and with lower values of Kc. Fig. 4 C indicates that Kc and [IP3] have a similar effect on the diastolic Ca2+ concentration except that the location of the red and orange cross predicts a small (∼10%) drop in diastolic Ca2+. In Fig. 4, A–C, there is little change when [IP3] is low and Kc is high (bottom right corner of each image). This is a regime in which the IP3R channels barely open in response to ECC transients. For comparison, Fig. S2 shows the same simulations as Fig. 4 at a commonly used experimental pacing frequency of 0.3 Hz, showing similar trends.

To compare our simulation results with the experimental observations summarized in Table 1, we divided the parameter space shown in Fig. 4, A–C into four regions, shown in Fig. 4 D. In the red region, amplitude and FDHM increase. In the orange region, only FDHM increases. In the green region, FDHM and diastolic [Ca2+] increase, but amplitude decreases. Comparing to the experimental observation of amplitude increase summarized in Table 1, the red region appears to describe the most plausible parameter range. Fig. 4 D also shows that there is no parameter set in which both amplitude and diastolic Ca2+ concentration increase. Furthermore, there is no region in which transients with increased amplitude and decreased duration are observed, as has been reported in ET-1-treated rat ventricular myocyte experiments (54). Finally, with the exception of the blue region in which there is no change, we observe that the FDHM increases in all parameter regimes.

To examine these results further, we investigated model behavior in different regions of Fig. 4 D, shown in Fig. 5 and marked as green, red, and orange crosses in Fig. 4, A–C. Comparing the green cytosolic profiles (corresponding to the green region in Fig. 4 D) and blue cytosolic Ca2+ profiles (corresponding to no IP3R activation) in Fig. 5, we find that IP3R opening at diastolic Ca2+ levels and IP3R inhibition at Ca2+ levels below peak transient concentrations generates a flatter Ca2+ transient. This is the result of a gradual depletion of SR Ca2+ stores from IP3Rs opening. This subsequently leads to lower Ca2+ release through RyR and IP3R channels.

Figure 5.

Simulated ECC transient and fluxes in the absence (blue) and presence of IP3, corresponding to low (green), medium (orange), and high (red) values of Kc. With Kc = 8 μM (orange), IP3R channels open only at Ca2+ concentrations greater than 0.1 μM. This results in increased peak in cytosolic Ca2+ transients and depleted SR Ca2+ stores. Parameters here were selected to show absence of IP3R channels (blue), increased transient amplitude (orange, red), and IP3Rs parameterized as described in the original Siekmann-Cao-Sneyd model (green). IP3 concentration is 10 μM and pacing frequency 1 Hz in all simulations. The sign of INCX indicates whether Ca2+ is moving into (positive) or out of (negative) the cell. To see this figure in color, go online.

Interestingly, a delayed time to peak is observed with IP3R activation in all regimes selected. With the reduction in SR load due to IP3R activation, we find reduced Ca2+ flux through RyRs. To maintain or increase Ca2+ transient amplitude after activation, the IP3R channels must compensate for the drop in RyR flux. Because the spike in IP3R flux is in response to Ca2+ release from RyR channels and initial RyR-mediated Ca2+ release is slower with lower SR Ca2+ stores, it delays the time between cell stimulation and Ca2+ transient peak.

The increase in FDHM of the transient from IP3R activation apparent in Fig. 4 B can be explained by continued release of Ca2+ through IP3R channels after RyRs have closed in Fig. 5. The slower release through IP3R channels after RyRs close is a result of a smaller proportion of the channels opening and a decrease in SR Ca2+ store load.

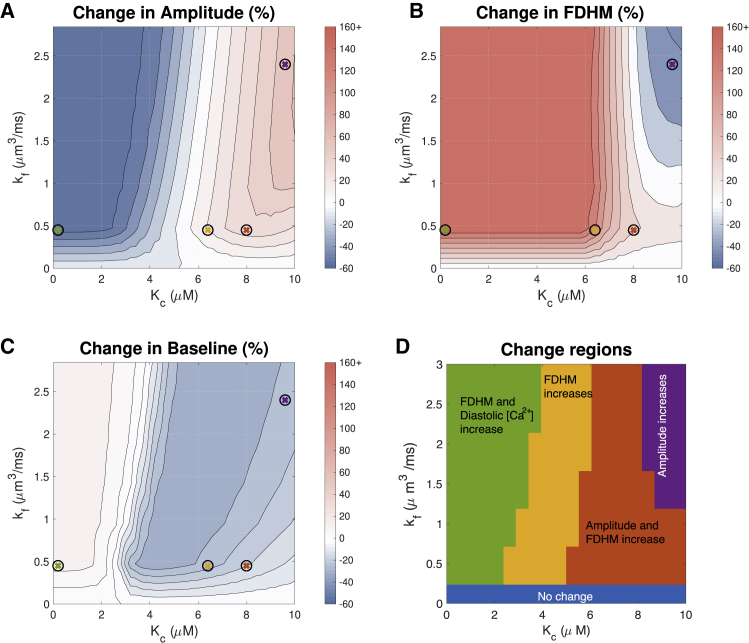

Maximal flux through IP3Rs can increase signal duration

The parameter sensitivity analysis in Table 2 indicates that maximal flux through IP3Rs (kf) has the greatest effect on Ca2+ transient duration. Therefore, we next examined how increased kf-values in our model affect the Ca2+ transient. Fig. 6, A–C show that for Kc < 2 μM, increasing kf above 0.45 μm3 ms−1 mostly increases transient duration but has only marginal effects on amplitude and baseline. However, for large Kc, the role of kf in modifying transient shape becomes more noticeable. There is a clear region in which amplitude increases (red region); however, this is more dependent on Kc than kf. At 1 Hz, there is no value of kf that reduces transient duration. With IP3R activation, the transient duration increases, and kf merely determines by how much. However it is of note that, as shown in Fig. 7, at a lower frequency of 0.3 Hz, when kf > 1.2 μm3 ms−1 and Kc > 8 μM, there is a decrease in duration of the transient.

Figure 6.

Effect of maximal IP3R flux kf and the Ca2+ sensitivity parameter Kc on the Ca2+ transient at 1 Hz. Maximal IP3R flux has the greatest impact on transient duration. In these simulations, [IP3] = 10 μM. See Fig. 5 for simulated transients at parameters indicated by crosses. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 7.

Effect of maximal IP3R flux kf and the Ca2+ sensitivity parameter Kc on the Ca2+ transient at 0.3 Hz. Maximal IP3R flux has the greatest impact on transient duration. In these simulations, [IP3] = 10 μM. See Fig. S3 for simulated transients at parameter values indicated by crosses. To see this figure in color, go online.

To compare simulation results to experimental observations in Table 1, we divided the parameter space shown in Fig. 6, A–C into three regions, shown in Fig. 6 D. The regions in this figure are consistent with the regions labeled in Fig. 4 D. Fig. 7 D shows similar regions corresponding to simulations at 0.3 Hz. It can be seen that at 0.3 Hz, Kc > 8 μM and kf > 1.2 μm3 ms−1 provide transients with increased amplitude and decreased duration, consistent with the rat ET-1 experiments summarized in Table 1. However, this value of kf results in an unrealistic flux through IP3R channels. Additionally, in vivo, the cell would be paced at a faster frequency, and this result is unlikely without the cell being able to return to resting Ca2+. We have not been able to identify a parameter set that would provide a simultaneous increase in both amplitude and diastolic Ca2+.

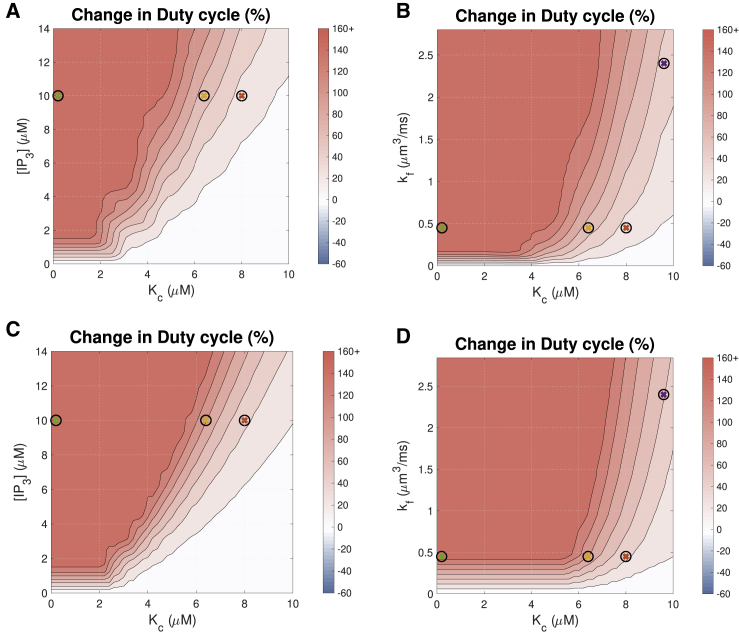

RyR and IP3R interaction increases the intracellular Ca2+ duty cycle

Having established reasonable parameter ranges for IP3R activation based on the influence on ECC Ca2+ transient properties (amplitude, FDHM, and diastolic Ca2+), we investigated the possibility that cytosolic Ca2+ plays a role in hypertrophic remodeling through changing the duty cycle. Given the timescale involved in hypertrophic remodeling and the signal integration properties of NFAT, the IP3R -modified cytosolic Ca2+ transient could cumulatively encode hypertrophic signaling. Using optogenetic encoding of cytosolic Ca2+ transients in HeLa cells, Hannanta-anan and Chow (8) demonstrated that the transcriptional activity of NFAT4 can be upregulated by increasing the cytosolic Ca2+ duty cycle. This is a plausible mechanism of signal encoding that is likely to be less susceptible to noise than either amplitude or frequency encoding. Therefore, we examined the cytosolic Ca2+ duty cycle as a hypertrophic signaling mechanism.

We calculated the duty cycle for the Ca2+ transients in the plausible parameter ranges for IP3R activation as the ratio between the area under the Ca2+ transient curve and the area of the bounded box defined by the amplitude and period of the Ca2+ transient (shown in Fig. 2). Fig. 8 shows the effects of [IP3], kf, and Kc on the duty cycle of the cytosolic Ca2+ transient. The figure shows that the Ca2+ duty cycle increases with IP3R activation across the broad parameter range shown.

Figure 8.

Effects on the Ca2+ transient duty cycle of (A) IP3 concentration and the Ca2+ sensitivity parameter Kc with pacing frequency 1 Hz, (B) maximal IP3R flux kf and Kc with pacing frequency 1 Hz, (C) IP3 concentration and Kc with pacing frequency 0.3 Hz, and (D) maximal IP3R flux kf and Kc at pacing frequency 0.3 Hz. The color bar indicates the percent change from a simulation run with identical parameters but no IP3R channels. The colored crosses indicate the parameters used for the corresponding plots in Fig. 5. Hannanta-anan and Chow (8) report a transcription rate increase of ∼30% with a duty cycle increase of 50% in Fig. 2 of their work. The duty cycle of the Ca2+ transient when IP3Rs are inactive is 0.127. To see this figure in color, go online.

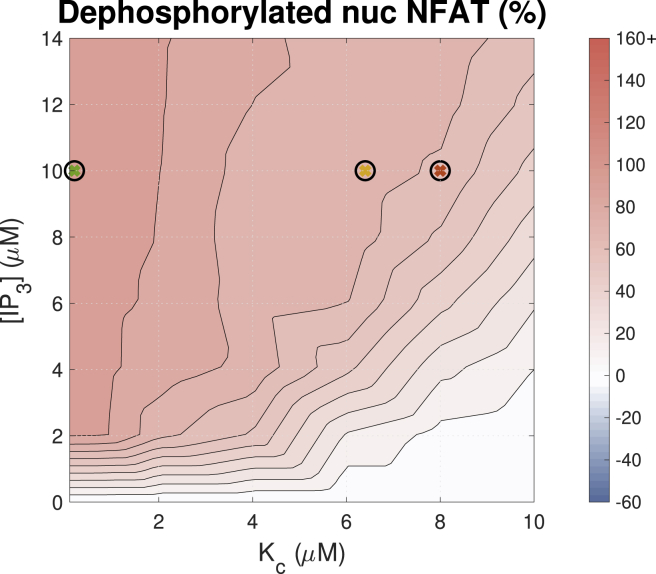

NFAT activation increases with an increase in calcium duty cycle

Having established that IP3R activation results in increased calcium transient duty cycle, we coupled the model of cytosolic ARVM calcium dynamics to the model of NFAT activation developed by Cooling et al. (50). We then tested the effect of varying IP3 concentration over a range of IP3R parameter values on the proportion of dephosphorylated nuclear NFAT compared with that in the phosphorylated inactive state in the cytosol (Fig. 9). These simulation data clearly show that increased IP3 and alteration in the Ca2+ transient duty cycle positively influence NFAT activation and thus provides a mechanism to couple IP3-induced Ca2+ release and activation of hypertrophic gene expression.

Figure 9.

Effect of [IP3] and Kc on the concentration of dephosphorylated nuclear NFAT (NFATn). Simulations were paced at 1 Hz. The color bar indicates the percent change from a simulation run with identical parameters but no IP3. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

Here, we have presented what is, to our knowledge, the first modeling study to investigate the effect of IP3R channel activity on the cardiac ECC Ca2+ transient and possible information encoding mechanisms. We extended a well-established model of the ECC Ca2+ transient by Hinch et al. (14) to include a model of IP3R activation and Ca2+ release. The model, upon IP3R activation, simulates the influence of IP3R activation on Ca2+ transients in nonhypertrophic adult rat left ventricular cardiac myocytes.

Parameter sensitivity analysis (Table 2) showed the maximal IP3-induced Ca2+ release through individual IP3R (kf) had the greatest influence on the Ca2+ transient duration and duty cycle. [IP3] had the biggest influence on the Ca2+ amplitude and diastolic Ca2+ concentration. We found that under fixed maximal IP3R flux, kf = 0.45 μm3 ms−1, IP3R activation increases the duration of the Ca2+ transient, but Ca2+ amplitude is IP3 dependent. The Ca2+ transient duration can be reduced only by increasing kf to physiologically unrealistic values.

The finding that the Ca2+ transient duty cycle increases with [IP3] (see Fig. 8) provides a plausible explanation for the mechanism by which IP3-dependent Ca2+ release from IP3Rs can enhance pro-hypertrophic NFAT activity.

Does IP3-induced Ca2+ release modify the ECC transient?

Figs. 4, 6 and 7 show that IP3Rs can influence the ECC Ca2+ transient and that the effect is dependent on the IP3R properties and IP3 concentration. Our model simulations predict that Ca2+ transient amplitude increases ∼15% when IP3R properties are such that IP3Rs remain inhibited from opening at diastolic Ca2+ but release Ca2+ once RyRs are activated and remain open when Ca2+ concentration is above 1 μM. The IP3R parameter combination marked by a red cross in the contour plots is a representative example of this type of effect of IP3Rs. There is also a narrow parameter range at [IP3] of 10 μM (Kh = 2.2 μM, Kc = 6 μM) in which the amplitude does not change more than 5% (see Fig. 4). The orange cross marks an example of IP3R effects in this parameter range. These simulation predictions are consistent with the experimental studies that either show increased amplitude or no change in amplitude (Table 1).

Model simulations predict that IP3R activation only increases diastolic [Ca2+] when IP3Rs are open at resting [Ca2+] of ∼0.1 μM (see Fig. 4 D). Harzheim et al. (17) reported no measurable differences in diastolic [Ca2+] between ARVMs stimulated with an agonist known to induce hypertrophy in healthy ARVMs and those treated with a saline buffer (although effects have been observe in disease ventricular cardiomyocytes and atrial cardiomyocytes). Examination of simulated Ca2+ transients within a regime that results in diastolic [Ca2+] increase (green traces in Fig. 5) shows that the transients do not resemble any of the observed experimental measurements in the literature. Therefore, the comparison of model simulations and experimental measurements of diastolic [Ca2+] and Ca2+ transient amplitude suggest that the most likely regime of IP3R activation lies between the orange and red regions in Fig. 4 D. Using these comparisons, we propose that IP3R activation makes modest changes to the ECC Ca2+ transient that are often hidden within the measurement variability in experiments.

The biological significance of the duty cycle

We showed that although amplitude, duration, and diastolic Ca2+ can increase or decrease depending on IP3R parameter values and pacing frequency, the duty cycle, as defined by Hannanta-anan and Chow (8), always increases with IP3, consistent with effects seen in (21). The implication of this observation is that IP3R activation is sufficient to provide a signal to drive NFAT nuclear translocation and hence hypertrophic gene expression in the manner described by Hannanta-anan and Chow (8).

Hannanta-anan and Chow (8) found that when comparing Ca2+ oscillations of the same amplitude, oscillations with greater duty cycle had a greater effect on NFAT dephosphorylation and translocation to the nucleus. In their study, duty cycle, γ, was calculated as the area under the curve, U, divided by the maximal area under the curve (for Ca2+ oscillations of the same amplitude, A, and period of oscillation, T), i.e., γ = U/AT (see Fig. 2 A). An alternative definition is γ = Δ/T, where Δ is the transient duration and T the period of oscillation. This alternate formulation is used by Tomida et al. (37) and Salazar et al. (55) but is less well defined for analog signals. The duty cycle in Fig. 8 was calculated using the former definition. This can be compared with the latter definition when remembering that duty cycle will now vary with FDHM (Figs. 4 C and 6 C).

The duty cycle in this system essentially reflects the fraction of each period of the Ca2+ cycle for which cytosolic Ca2+ is sufficiently elevated to affect the downstream proteins in the CnA/NFAT signaling pathway. The greater sensitivity of NFAT to Ca2+ oscillations with sustained elevation in intracellular Ca2+ is well established (19,38,56). Although it is difficult to determine where this threshold is, NFAT is a Ca2+ integrator, and a clear correlation has been found between Ca2+ duty cycle and NFAT activation (8). Increasing duty cycle increases the time NFAT spends in the dephosphorylated state, which is required to both enter and maintain it in the nucleus and hence affects transcription (57); NFAT responds to changes in duty cycle while being insensitive to both amplitude and frequency changes. We see in simulations too that the proportion of NFAT that is in the dephosphorylated nuclear state is highest when the duty cycle of the Ca2+ transient is high (Figs. 8 and 9).

In experiments, IP3 stimulation has been shown to lead to an increase in systolic Ca2+ in cardiac cells, but a significant change in duration has not been reported (although as in Harzheim et al. (17) and Proven et al. (21), increased spontaneous calcium transients are observed that could function to prolong the duration of the Ca2+ transient). Based on the definition of the duty cycle presented in Hannanta-anan and Chow (8), there is a negative effect on duty cycle, and hence NFAT activation, when Ca2+ transient amplitude is increased. However, within the physiologically plausible parameter range, we find that simulations with increased Ca2+ transient amplitude also have increased transient duration. We postulate that NFAT may be responsive to the Ca2+ transient through the latter definition of the duty cycle—i.e., the duration of time that Ca2+ is elevated over a threshold divided by the period. This is more consistent with both the biological mechanism and the potential increase in peak Ca2+ concentration in the hypertrophic pathway, which may be a side effect of a corresponding increase in duration over this threshold. Further research, both theoretical and experimental, is required to determine the validity of this assumption.

Fig. 9 shows a strong correlation between [Ca2+]-dependent NFAT activation and Ca2+ transient duty cycle in the Cooling et al. (50) model; the correspondence between Figs. 8 A and 9 is striking. A caveat, however, is that the original Cooling et al. (50) study showed that the NFAT model is also sensitive to any average increase in cytosolic calcium. Therefore, although increasing Ca2+ transient duty cycle is shown to be sufficient for NFAT activation in this model, further experimental validation is required to confirm this mechanism in cardiomyocytes.

Experimental evidence of an IP3-induced increase in calcium duty cycle?

An increase in duty cycle without an increase in frequency requires an increase in transient duration. Although this increase is observed in our simulations for a broad range of parameter values, it has not, however, been reported in experiments involving IP3 stimulation. The possible reasons for this are many and varied; however, as discussed earlier, using different IP3 concentrations to those that occur in vivo may result in different effects on the shape of the Ca2+ oscillations, leading to inconsistent observations. Furthermore, small variations in Ca2+ concentrations may not be experimentally discernible or may be hidden by the effect of Ca2+-sensitive dyes (58). A small but prolonged variation in transient duration can produce a comparatively large change in duty cycle. Hence, it remains to be confirmed experimentally whether IP3R-dependent Ca2+ flux does indeed lead to an increased Ca2+ duty cycle in cardiomyocytes.

Limitations of study

In this study, we have considered generation of voltage-driven cytosolic Ca2+ transients using deterministic models of each ion channel in a compartmental model. There are several physiological features of cardiomyocyte Ca2+ dynamics that are not represented and hence not considered in this approach. In particular, our model does not represent any of the stochastic events associated with IP3R channels. Further modeling of combined stochastic channel gating may be necessary to elucidate the entire impact of IP3R interaction with the cytosolic Ca2+ machinery. Although cell structure is known to play a role in cardiac Ca2+ dynamics (59, 60, 61), effects beyond the synchronizing function of the dyad are not considered in this compartmental study. Furthermore, we have not considered the spatial IP3R distribution. Our model is developed primarily using parameters fitted by (14) and (32) and makes no distinction between IP3R channels located within or outside the dyad (62,63). These and other structural features of the cell could alter the Ca2+ available to regulate IP3R channels and may be detected in the Ca2+ transient. Distinct effects of IP3 signaling in the cytosol and the nucleus are also not considered. Cytosolic Ca2+ is thought to promote translocation of NFAT into the nucleus, whereas nuclear Ca2+ maintains it there (16). We have only investigated the former role for Ca2+ signaling within the CnA/NFAT pathway.

We have explored model behavior at pacing frequencies of 1 and 0.3 Hz rather than higher, more physiological frequencies, primarily because the majority of parameters were derived from in vitro experiments conducted at room temperature. Extrapolation of parameters, and hence model behavior, to in vivo temperature and correspondingly higher pacing frequency remains challenging. Therefore, model predictions must be interpreted cautiously in relation to higher pacing frequencies.

Additionally, not all components of this signaling pathway have been considered in this study. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinases II and Class IIa histone deacetylases, for example, are both known Ca2+-mediated components of the hypertrophic pathway that are activated by IP3 signaling (64) but are not included. Here, we have focused only on the impact of IP3R activation on the cytosolic Ca2+ dynamics and how this relates to the mechanism of NFAT activation. To explore broader context for IP3-mediated hypertrophic signaling, it remains to couple this model to upstream events, including models of IP3 production through activation of cell membrane receptors (65,66). This would allow the profile and extent of the rise in IP3 concentration due to the activation of the hypertrophic pathway in cardiomyocytes to be determined. We have focused on the effect of an elevated IP3 concentration of 10 μM because many experimental studies on the effect of IP3 on Ca2+ dynamics use saturating [IP3]. However, Remus et al. (67) found stimulation of adult cat ventricular myocytes with 100 nM ET-1 induced a cell-averaged increase in IP3 concentration of only 10 nM, indicating a much lower concentration than used in experiments. This, together with known differences between species, suggests the IP3 concentration detected by IP3R receptors in ARVMs in vivo could be lower than the simulated 10 μM. However, we note qualitatively similar effects on the Ca2+ transient in parameter regimes with lower [IP3] in our model (Figs. 4 and S2), albeit with more modest effects on the transient shape. Additionally, ET-1 receptors are localized to t-tubule membranes (68), so IP3 may be generated very close to IP3R channels (63,69), increasing the concentration they detect.

Finally, IP3R-induced Ca2+ release is a part of a larger hypertrophic signaling network. It remains to couple this model to other signaling pathways involved in bringing about hypertrophic remodeling (70). How cytosolic Ca2+ interacts with nuclear Ca2+ in regulation of NFAT nuclear residence and activity also remains to be determined.

Conclusions

The sensitivity of NFAT translocation to the Ca2+ duty cycle demonstrated by Hannanta-anan and Chow (8) raises the question as to whether IP3R flux can increase the Ca2+ duty cycle in cardiomyocytes during hypertrophic signaling. Here, we have shown, using mathematical modeling, that an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ transient duration can occur after addition of IP3, and furthermore, that this increase is sufficient to increase NFAT activation. Together, these results suggest a plausible mechanism for hypertrophic signaling via IP3R activation in cardiomyocytes. Although it cannot be ruled out that a significant role is played by components of this pathway that are not considered here, the computational evidence provided in this study, along with the previous experimental findings, suggests encoding of the hypertrophic signal through alteration of the duration of cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations to be a feasible mechanism for IP3-dependent hypertrophic signaling.

Author Contributions

E.J.C., V.R., H.L.R., C.S., and G.B. conceived of the study. E.J.C. and V.R. supervised the project. H.H., A.T., V.R., and E.J.C. developed the modeling approach. H.H. implemented the simulations. H.L.R., C.S., and G.B. provided critical feedback. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council Discovery Projects funding scheme (project DP170101358). H.L.R. wishes to acknowledge financial support from the Research Foundation Flanders through project grant G08861N and Odysseus programme grant 90663.

Editor: Eric Sobie.

Footnotes

Vijay Rajagopal and Edmund J. Crampin contributed equally to the supervision of this work.

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.08.001.

Contributor Information

Vijay Rajagopal, Email: vijay.rajagopal@unimelb.edu.au.

Edmund J. Crampin, Email: edmund.crampin@unimelb.edu.au.

Supporting Citations

References (71,72) appear in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Berridge M.J., Bootman M.D., Roderick H.L. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clapham D.E. Calcium signaling. Cell. 2007;131:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berridge M.J. The AM and FM of calcium signalling. Nature. 1997;386:759–760. doi: 10.1038/386759a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berridge M.J. Calcium microdomains: organization and function. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bootman M.D., Fearnley C., Roderick H.L. An update on nuclear calcium signalling. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:2337–2350. doi: 10.1242/jcs.028100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purvis J.E., Lahav G. Encoding and decoding cellular information through signaling dynamics. Cell. 2013;152:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uzhachenko R., Shanker A., Dupont G. Computational properties of mitochondria in T cell activation and fate. Open Biol. 2016;6:160192. doi: 10.1098/rsob.160192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hannanta-Anan P., Chow B.Y. Optogenetic control of calcium oscillation waveform defines NFAT as an integrator of calcium load. Cell Syst. 2016;2:283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roderick H.L., Higazi D.R., Bootman M.D. Calcium in the heart: when it’s good, it’s very very good, but when it’s bad, it’s horrid. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007;35:957–961. doi: 10.1042/BST0350957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hohendanner F., Maxwell J.T., Blatter L.A. Cytosolic and nuclear calcium signaling in atrial myocytes: IP3-mediated calcium release and the role of mitochondria. Channels (Austin) 2015;9:129–138. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2015.1040966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zinn M., West S., Kuhn B. Mechanisms of cardiac hypertrophy. In: Jefferies J.L., Chang A.C., Rossano J.W., Shaddy R.E., Towbin J.A., editors. Heart Failure in the Child and Young Adult. Academic Press; 2018. pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tham Y.K., Bernardo B.C., McMullen J.R. Pathophysiology of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure: signaling pathways and novel therapeutic targets. Arch. Toxicol. 2015;89:1401–1438. doi: 10.1007/s00204-015-1477-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbert G., Demydenko K., Roderick H.L. Calcium signaling in cardiomyocyte function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2020;12:035428. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a035428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinch R., Greenstein J.L., Winslow R.L. A simplified local control model of calcium-induced calcium release in cardiac ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 2004;87:3723–3736. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vierheller J., Neubert W., Chamakuri N. A multiscale computational model of spatially resolved calcium cycling in cardiac myocytes: from detailed cleft dynamics to the whole cell concentration profiles. Front. Physiol. 2015;6:255. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higazi D.R., Fearnley C.J., Roderick H.L. Endothelin-1-stimulated InsP3-induced Ca2+ release is a nexus for hypertrophic signaling in cardiac myocytes. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harzheim D., Movassagh M., Roderick H.L. Increased InsP3Rs in the junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum augment Ca2+ transients and arrhythmias associated with cardiac hypertrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:11406–11411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905485106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakayama H., Bodi I., Molkentin J.D. The IP3 receptor regulates cardiac hypertrophy in response to select stimuli. Circ. Res. 2010;107:659–666. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.220038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rinne A., Kapur N., Blatter L.A. Isoform- and tissue-specific regulation of the Ca(2+)-sensitive transcription factor NFAT in cardiac myocytes and heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010;298:H2001–H2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01072.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Signore S., Sorrentino A., Rota M. Inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate receptors and human left ventricular myocytes. Circulation. 2013;128:1286–1297. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proven A., Roderick H.L., Bootman M.D. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate supports the arrhythmogenic action of endothelin-1 on ventricular cardiac myocytes. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:3363–3375. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domeier T.L., Zima A.V., Blatter L.A. IP3 receptor-dependent Ca2+ release modulates excitation-contraction coupling in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008;294:H596–H604. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01155.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ljubojevic S., Radulovic S., Pieske B. Early remodeling of perinuclear Ca2+ stores and nucleoplasmic Ca2+ signaling during the development of hypertrophy and heart failure. Circulation. 2014;130:244–255. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olivares-Florez S., Czolbe M., Ritter O. Nuclear calcineurin is a sensor for detecting Ca2+ release from the nuclear envelope via IP3R. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 2018;96:1239–1249. doi: 10.1007/s00109-018-1701-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smyrnias I., Goodwin N., Roderick H.L. Contractile responses to endothelin-1 are regulated by PKC phosphorylation of cardiac myosin binding protein-C in rat ventricular myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018;117:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harzheim D., Talasila A., Roderick H.L. Elevated InsP3R expression underlies enhanced calcium fluxes and spontaneous extra-systolic calcium release events in hypertrophic cardiac myocytes. Channels (Austin) 2010;4:67–71. doi: 10.4161/chan.4.1.10531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foskett J.K., White C., Mak D.-O.D. Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:593–658. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramos-Franco J., Bare D., Mignery G. Single-channel function of recombinant type 2 inositol 1,4, 5-trisphosphate receptor. Biophys. J. 2000;79:1388–1399. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76391-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siekmann I., Sneyd J., Crampin E.J. Statistical analysis of modal gating in ion channels. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2014;470:20140030. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siekmann I., Cao P., Crampin E.J. Data-driven modelling of the inositol trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) and its role in calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) In: De Pittà M., Berry H., editors. Computational Glioscience. Springer International Publishing; 2019. pp. 39–68. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao P., Tan X., Sneyd J. A deterministic model predicts the properties of stochastic calcium oscillations in airway smooth muscle cells. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sneyd J., Han J.M., Yule D.I. On the dynamical structure of calcium oscillations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:1456–1461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614613114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siekmann I., Sneyd J., Crampin E.J. MCMC can detect nonidentifiable models. Biophys. J. 2012;103:2275–2286. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terkildsen J.R., Niederer S., Smith N.P. Using Physiome standards to couple cellular functions for rat cardiac excitation-contraction. Exp. Physiol. 2008;93:919–929. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.041871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkins B.J., De Windt L.J., Molkentin J.D. Targeted disruption of NFATc3, but not NFATc4, reveals an intrinsic defect in calcineurin-mediated cardiac hypertrophic growth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:7603–7613. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7603-7613.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molkentin J.D., Lu J.R., Olson E.N. A calcineurin-dependent transcriptional pathway for cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 1998;93:215–228. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81573-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomida T., Hirose K., Iino M. NFAT functions as a working memory of Ca2+ signals in decoding Ca2+ oscillation. EMBO J. 2003;22:3825–3832. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colella M., Grisan F., Pozzan T. Ca2+ oscillation frequency decoding in cardiac cell hypertrophy: role of calcineurin/NFAT as Ca2+ signal integrators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:2859–2864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712316105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saucerman J.J., Bers D.M. Calmodulin mediates differential sensitivity of CaMKII and calcineurin to local Ca2+ in cardiac myocytes. Biophys. J. 2008;95:4597–4612. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.128728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ulrich J.D., Kim M.-S., Usachev Y.M. Distinct activation properties of the nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) isoforms NFATc3 and NFATc4 in neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:37594–37609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.365197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yissachar N., Sharar Fischler T., Friedman N. Dynamic response diversity of NFAT isoforms in individual living cells. Mol. Cell. 2013;49:322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kar P., Mirams G.R., Parekh A.B. Control of NFAT isoform activation and NFAT-dependent gene expression through two coincident and spatially segregated intracellular Ca2+ signals. Mol. Cell. 2016;64:746–759. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandit S.V., Giles W.R., Demir S.S. A mathematical model of the electrophysiological alterations in rat ventricular myocytes in type-I diabetes. Biophys. J. 2003;84:832–841. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74902-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wagner J., Keizer J. Effects of rapid buffers on Ca2+ diffusion and Ca2+ oscillations. Biophys. J. 1994;67:447–456. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80500-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moschella M.C., Marks A.R. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor expression in cardiac myocytes. J. Cell Biol. 1993;120:1137–1146. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.5.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siekmann I., Wagner L.E., II, Sneyd J. A kinetic model for type I and II IP3R accounting for mode changes. Biophys. J. 2012;103:658–668. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramos-Franco J., Fill M., Mignery G.A. Isoform-specific function of single inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor channels. Biophys. J. 1998;75:834–839. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77572-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zima A.V., Bovo E., Blatter L.A. Ca2+ spark-dependent and -independent sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in normal and failing rabbit ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. 2010;588:4743–4757. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.197913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blanch I Salvador J., Egger M. Obstruction of ventricular Ca2+ -dependent arrhythmogenicity by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-triggered sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release. J. Physiol. 2018;596:4323–4340. doi: 10.1113/JP276319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooling M.T., Hunter P., Crampin E.J. Sensitivity of NFAT cycling to cytosolic calcium concentration: implications for hypertrophic signals in cardiac myocytes. Biophys. J. 2009;96:2095–2104. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jansen M.J.W. Analysis of variance designs for model output. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1999;117:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saltelli A., Annoni P., Tarantola S. Variance based sensitivity analysis of model output. Design and estimator for the total sensitivity index. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2010;181:259–270. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greenstein J.L., Winslow R.L. An integrative model of the cardiac ventricular myocyte incorporating local control of Ca2+ release. Biophys. J. 2002;83:2918–2945. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75301-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moravec C.S., Reynolds E.E., Bond M. Endothelin is a positive inotropic agent in human and rat heart in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989;159:14–18. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salazar C., Politi A.Z., Höfer T. Decoding of calcium oscillations by phosphorylation cycles: analytic results. Biophys. J. 2008;94:1203–1215. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.113084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dolmetsch R.E., Lewis R.S., Healy J.I. Differential activation of transcription factors induced by Ca2+ response amplitude and duration. Nature. 1997;386:855–858. doi: 10.1038/386855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feske S., Draeger R., Rao A. The duration of nuclear residence of NFAT determines the pattern of cytokine expression in human SCID T cells. J. Immunol. 2000;165:297–305. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sparrow A.J., Sievert K., Daniels M.J. Measurement of myofilament-localized calcium dynamics in adult cardiomyocytes and the effect of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations. Circ. Res. 2019;124:1228–1239. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gaur N., Rudy Y. Multiscale modeling of calcium cycling in cardiac ventricular myocyte: macroscopic consequences of microscopic dyadic function. Biophys. J. 2011;100:2904–2912. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rajagopal V., Bass G., Soeller C. Examination of the effects of heterogeneous organization of RYR clusters, myofibrils and mitochondria on Ca2+ release patterns in cardiomyocytes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004417–e1004431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ladd D., Tilūnaitė A., Rajagopal V. Assessing cardiomyocyte excitation-contraction coupling site detection from live cell imaging using a structurally-realistic computational model of calcium release. Front. Physiol. 2019;10:1263. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mohler P.J., Schott J.-J., Bennett V. Ankyrin-B mutation causes type 4 long-QT cardiac arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. Nature. 2003;421:634–639. doi: 10.1038/nature01335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mohler P.J., Davis J.Q., Bennett V. Ankyrin-B coordinates the Na/K ATPase, Na/Ca exchanger, and InsP3 receptor in a cardiac T-tubule/SR microdomain. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu X., Zhang T., Bers D.M. Local InsP3-dependent perinuclear Ca2+ signaling in cardiac myocyte excitation-transcription coupling. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:675–682. doi: 10.1172/JCI27374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cooling M., Hunter P., Crampin E.J. Modeling hypertrophic IP3 transients in the cardiac myocyte. Biophys. J. 2007;93:3421–3433. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.110031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cooling M.T., Hunter P.J., Crampin E.J. Modelling biological modularity with CellML. IET Syst. Biol. 2008;2:73–79. doi: 10.1049/iet-syb:20070020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Remus T.P., Zima A.V., Mignery G.A. Biosensors to measure inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate concentration in living cells with spatiotemporal resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:608–616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509645200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boivin B., Chevalier D., Allen B.G. Functional endothelin receptors are present on nuclei in cardiac ventricular myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:29153–29163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Escobar M., Cardenas C., Franzini-Armstrong C. Structural evidence for perinuclear calcium microdomains in cardiac myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011;50:451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ryall K.A., Holland D.O., Saucerman J.J. Network reconstruction and systems analysis of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:42259–42268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.382937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu T., Lloyd C.M., Nielsen P.M.F. The physiome model repository 2. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:743–744. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomas D., Tovey S.C., Lipp P. A comparison of fluorescent Ca2+ indicator properties and their use in measuring elementary and global Ca2+ signals. Cell Calcium. 2000;28:213–223. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Escobar A.L., Perez C.G., Ramos-Franco J. Role of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate in the regulation of ventricular Ca(2+) signaling in intact mouse heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012;53:768–779. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.