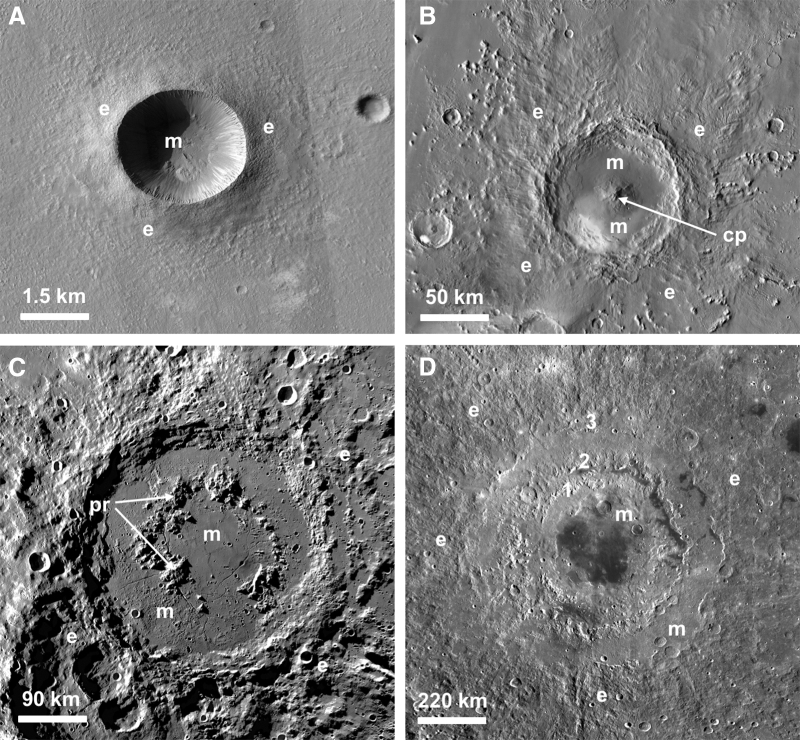

FIG. 1.

Images of impact craters showing the change in morphology with increasing size. (A) The 3 km diameter Zumba Crater on Mars, a prototypical simple crater. Note the impact ejecta deposits (“e”) and the impact melt deposits (“m”) on the crater floor. Portion of Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) image PSP_003608_1510. NASA/JPL/University of Arizona. (B) The 93 km diameter Pettit Crater on Mars, a well-preserved complex crater with a central peak (“cp”). THEMIS day-time mosaic. NASA/JPL/Arizona State University. (C) With increasing diameter, central peaks are replaced by peak-rings (“pr”) as in the case of the ∼320 km diameter Schrödinger Crater on the Moon. The crater has well-preserved ejecta deposits, and impact melt occurs both inside and outside the peak-ring. Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) Wide Angle Camera (WAC) mosaic. NASA/JPL/ASU. (D) The largest impact features in the Solar System are termed impact basins, such as the ∼900 km diameter Orientale Basin on the Moon shown here. It contains three ring features labeled 1–3. LRO WAC mosaic. NASA/JPL/ASU.