Abstract

Emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN) is a necrotizing infection characterized by the production of gas in the renal parenchyma, collecting system or perirenal tissue. Meanwhile, emphysematous cystitis (EC) is a clinical entity characterized by the presence of gas inside and around the bladder wall. Interestingly, although both diseases are common in patients with diabetes mellitus, these are rarely combined. We report a rare case of a 56-year-old diabetic male suffering from fever, headache and vomiting and in which a diagnosis of septic shock was established due to coexistence of EC and bilateral EPN. The emphysematous diseases improved with a conservative treatment approach using antibiotic therapy and glycemic control, we highlight that the nephrectomy was not necessary in our patient despite the fact that he presented risk factors that predict the failure of conservative treatment.

Keywords: Emphysematous pyelonephritis, Emphysematous cystitis, Computed tomography, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Septic shock

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease whose treatment has traditionally focused on glycemic control, but accumulating evidence suggests that the clinical management of patients requires a more comprehensive approach to minimize associated morbidity and mortality [1]. In this way, patients with diabetes are more prone to get urinary tract infection (UTI), because high levels of urine sugar provide a pathogen-friendly growth environment, where emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN), emphysematous cystitis (EC), renal and perinephric abscesses, urosepsis, and bacteremia are some common complications, although these are rarely combined.

Emphysematous pyelonephritis has been defined as a necrotizing infection of the renal parenchyma and its surroundings that results in the presence of gas in the renal parenchyma, collecting system or perinephrotic tissues [2]. Meanwhile, emphysematous cystitis is a clinical entity, characterized by the presence of gas inside and around the bladder wall produced by bacterial or fungal fermentation [3].

Here, we present a rare case of EC and bilateral EPN coexistence in a 56-year-old male who was successfully managed with medical treatment.

Case report

A 56-year-old male patient presented to the department of nephrology after 6 days suffering weakness, fever, headache and vomiting. The patient, who weighed 58 kg and had a height of 1.63 m (body mass index of 21.8), was previously diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) 18 years ago, maintaining a treatment with insulin glargine 10 IU/day and with regular glucose control. He also had a history of smoking for 40 years with 6 cigarettes per day, currently suspended.

Upon admission, the patient had a fever of 38.9 °C, tachypnea, tachycardia of 116 beats/min and hypotension with a systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg, showing sepsis data that were confirmed with paraclinical studies. Arterial gasometry revealed metabolic acidosis, hypoalbuminemia, serum sodium of 122 mmol/L, serum chloride of 91 mmol/L and serum potassium of 5.6 mmol/L. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio at admission was 9.71 and lactic acid was not measured, other laboratory results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of laboratory tests

| Laboratory tests | Patient results upon admission | Patient results upon discharge |

|---|---|---|

| Total leukocytes (103/µL) | 24.08 | 8.8 |

| Total neutrophils (103/µL) | 20.8 | 4.58 |

| Total lymphocytes (103/µL) | 2.14 | 2.26 |

| Band cells (%) | 85 | 3 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.3 | 12 |

| Platelets (103/µL) | 378 | 375 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 534 | 150 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 76.77 | 49.9 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 4.8 | 2.6 |

| General urine test | pH 5, protein traces, glucose 3+, leukocytes 30–35/field | pH 6, glucose 1+, leukocytes 5–8/field |

The renal ultrasound showed evidence of air in the parenchyma, where the left kidney measured 148 × 79 × 66 mm and the right kidney 128 × 73 × 57 mm, suggestive of EPN.

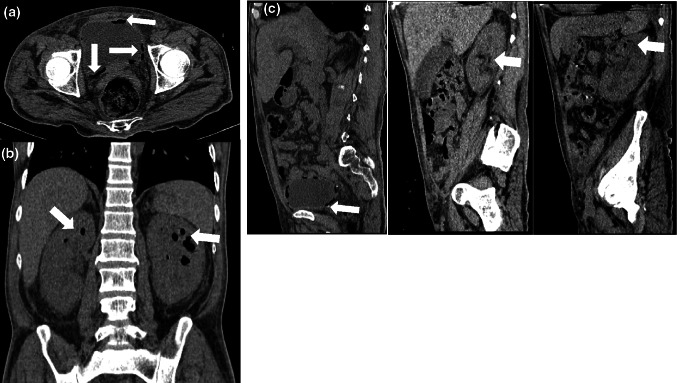

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showed bilateral EPN together with the presence of EC (Fig. 1). EPN was classified within the class 4 according to Huang et al. [2], which is considered the most serious.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal computed tomography without contrast. a The axial section showed air bladder and wall (arrow). b The coronal section showed enlarged bilateral kidney with parenchymal destruction and air densities (arrows) within the renal parenchyma. c The sagittal section showed air in the bladder, right and left kidney (arrows)

Patient blood and urine cultures showed growth of ESBL-positive Escherichia coli, with sensitivity to ertapenem, imipenem, meropenem, amikacin, tigecycline and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, but resistant to ampicillin, cefazolin, cefepime and ceftriaxone.

The patient received treatment by central venous catheter with intravenous fluids, intravenous antibiotics (initially empirical ceftriaxone and on the third day after admission it was changed to meropenem according to antibiotic sensitivity tests), insulin infusion and inotropic support with amines as well as bladder catheterization.

On the third day of hospitalization, our patient required renal replacement therapy due to acute renal injury with oliguria and refractory acidosis, so he received three sessions of hemodialysis (HD).

Urology service suggested conservative treatment, no percutaneous catheter drainage or nephrectomy. The patient's clinical conditions improved markedly on the fifth day of treatment, and 15 days after admission, the patient was afebrile, with total leukocytes of 8.8 × 103/μL, albumin 2.5 g/dL, serum creatinine 2.6 mg/dL, serum urea 164.8 mg/dL, serum sodium 134 mmol/L, serum chloride 100 mmol/L, serum potassium of 4.4 mmol/L and a neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio of 0.98. Other laboratory results are shown in Table 1.

The glomerular filtration rate was estimated one week after the last HD session with the modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) equation obtaining 26 mL/min/1.73m2.

The patient was discharged on day 17 after admission where the abdominal examination with control CT showed a complete resolution of renal and bladder emphysema, as well as an undeveloped control urine culture report.

Discussion

Solitary kidney with EPN and EC are, each separately, common in patients with DM2 or immunocompromised patients (patients with renal graft, who use steroids, with polycystic kidneys, neurogenic bladder, alcoholism, anatomical abnormalities, renal failure and immune suppression), with a female-to-male ratio of 4–6:1 [4, 5], and average age of 57 years [6]. However, bilateral EPN combined with EC in the same patient is a strange finding that has only been reported rarely.

Overall, EPN occurs in 90% of patients with poor diabetes mellitus control [2–4, 6, 7], whose most common pathogens involved are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, Clostridium septicum, Candida albicans, Pseudomonas, among others [2–4], and its clinical manifestation is similar to high urinary tract infection. Escherichia coli is the most common microorganism in EC and its clinical manifestation is mainly low irritative symptoms. CT scan is the best diagnostic method since it also allows to know the anatomical extension [3].

A meta-analysis reports that in 52% of cases of EPN the left kidney is affected, while 37.7% affects the right side [5], being bilateral only in 5–10.2% of cases [5, 7]. The diagnosis of EPN is classically made by demonstrating the presence of gas in the kidney or in the perirenal tissue by simple X-ray of the abdomen, renal ultrasound or CT scan [6, 7].

Based on the radiological results in the CT scan, Huang et al. [2] created a classification system that facilitates treatment:

Class 1: gas only in the collecting system (called emphysematous pyelitis).

Class 2: gas in the renal parenchyma without extension to the extrarenal space.

Class: 3A: extension of the gas or abscess to the perinephric space.

Class 3B: extension of the gas or abscess to the pararenal space.

Class 4: bilateral EPN or solitary kidney with EPN.

The differential diagnosis between emphysematous pyelitis (gas in the collecting system) and EPN (gas in the renal parenchyma) is very important, because EPN tends to be more severe, with a mortality of 18–33% in bilateral EPN [1, 2, 5].

High mortality has been reported in EPN patients who require emergency hemodialysis, present shock on initial presentation, altered mental status, severe hypoalbuminemia, inappropriate empirical antibiotic treatment and polymicrobial infection [8], as well as poor results were reported in the presence of thrombocytopenia [2]. However, Kolla et al. [9] reported improvement in eight patients only with conservative management without mortality.

The literature reports a mortality of 54% in patients with secondary shock to EPN [4]. Our patient was diagnosed with class 4 disease, had no thrombocytopenia, mental disorder or polymicrobial infection, but he had leukocytosis, hypoalbuminemia and manifest shock, inappropriate empirical antibiotic was used the first 3 days and required hemodialysis, which may be necessary in 62.5% of patients [9], therefore, he presented four risk factors of mortality, two of them also associated with the failure of conservative treatment. However, treatment according to international guidelines for the management of sepsis (intravenous fluids, antibiotic and supportive treatment) was successful, no requiring percutaneous catheter drainage or nephrectomy. In this regard, similar to that reported by other authors [10–15], our patient was recovered and hemodialysis was suspended. Nephrectomy is considered the last option.

In the cases presented in Table 2, the average age of the disease was 54.7 ± 11 years, most patients have diabetes and the predominant bacteria is Escherichia coli. Interestingly, six of the cases are in men, which contrasts with that reported for independent EPN where there is a higher prevalence in women. According to the literature, leukocytosis occurs in 70–80% of cases [5] and hypoalbuminemia (< 3 g/dL) was present in 50% [8]. In addition, two patients required percutaneous drainage, whereas only one patient needed bilateral nephrectomy, only one patient died, and the others recovered their health.

Table 2.

Previous reports of coexistence of EC and bilateral EPN in adults

| Author [References] | Age/gender | Diabetes mellitus/comorbidities | Bacteria | Treatment | Antibiotics used | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arun [10] | 64/M | Yes/ADPKD | E. coli/Staph. aureus | MM | Piperacillin-tazobactam/vancomycin | Recovered | |

| Behera [11] | 39/F | Yes | NM | MM + PCD | Meropenem/amikacin | Recovered | |

| Behera [11] | 69/M | Yes | NM | MM | Meropenem/teicoplanin | Death | |

| Lee [12] | 54/M | Yes | E. coli | MM + PCD + HD | Cefuroxime | Recovered | |

| Yeh [13] | 60/F | NM/HD/obesity/hypertension | E. coli/Enterococcus | MM + bilateral nephrectomy | Imipenem-cilastati/vancomycin | Recovered | |

| Wang [14] | 38/M | Yes/HD | E. coli | MM | Levofloxacin | Recovered | |

| Momin [15] | 58/M | Yes | E. cloacae | MM | Meropenem/ertapenem | Recovered | |

| Current | 56/M | Yes |

ESBL-positive E. coli |

MM + HD | Meropenem | Recovered | |

ADPKD autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease, F female, HD hemodialysis, M male, MM medical management, PCD percutaneous drainage, NM no mentioned

Patients with diabetes mellitus have several factors that can favor the development of bilateral EPN and EC in the same patient, such as hyperglycemic conditions that favor the growth of bacteria, a greater propensity to urinary tract necrosis due to stress or infection, and the low immunity of patients with chronic kidney disease, among others [14, 15].

Punatar et al. [16] described that there is 1.8 greater risk of an unfavorable outcome in those patients with a neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio greater than 5 at admission, which happened with our patient, who required three hemodialysis sessions and then recovered renal function.

Conclusion

Patient described here was a 56-year-old man with uncontrolled DM2 and Escherichia coli was the causative pathogen, where we highlight the coexistence of EC and bilateral EPN, which is rare to find. Furthermore, the medical treatment in our patient was successful and required only temporary renal replacement therapy. We emphasize that timely diagnosis and specific antibiotic treatment avoided the need for surgery and reduced the risk of mortality.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Standards of medical care in diabetes—2016: summary of revisions. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:S4–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Huang J-J, Tseng C-C. Emphysematous pyelonephritis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:797. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mnif MF, Kamoun M, Kacem FH, Bouaziz Z, Charfi N, Mnif F, et al. Complicated urinary tract infections associated with diabetes mellitus: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17(3):442–445. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.111637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ubee SS, McGlynn L, Fordham M. Emphysematous pyelonephritis. BJU Int. 2011;107:1474–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aboumarzouk OM, Hughes O, Narahari K, Coulthard R, Kynaston H, Chlosta P, et al. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: time for a management plan with an evidence-based approach. Arab J Urol. 2014;12:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morioka H, Yanagisawa N, Suganuma A, Imamura A, Ajisawa A. Bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis with a splenic abscess. Intern Med. 2013;52:147–150. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.8302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shigemura K, Yasufuku T, Yamashita M, Arakawa S, Fujisawa M. Bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis cured by antibiotics alone: a case and literature review. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2009;62:206–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu Y-C, Chiang B-J, Pong Y-H, Huang K-H, Hsueh P-R, Huang C-Y, et al. Predictors of failure of conservative treatment among patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:418. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolla PK, Madhav D, Reddy S, Pentyala S, Kumar P, Pathapati RM. Clinical profile and outcome of conservatively managed emphysematous pyelonephritis. ISRN Urol. 2012;2012:1–4. doi: 10.5402/2012/931982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arun N, Hussain A, Kapoor MM, Abul F. Bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis and emphysematous cystitis with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: is conservative management justified? Med Princ Pract. 2007;16:155–157. doi: 10.1159/000098371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behera V, Vasantha Kumar R, Mendonca S, Prabhat P, Naithani N, Nair V. Emphysematous infections of the kidney and urinary tract: a single-center experience. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant. 2014;25:823. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.135164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee I-K, Hsieh C-J, Liu J-W. Bilateral extensive emphysematous pyelonephritis. Med Princ Pract. 2009;18:149–151. doi: 10.1159/000189814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeh CL, Hsu KF. Bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis and cystitis in an ESRD patient presenting with septic shock. Acta Clin Belg. 2009;64(2):160–161. doi: 10.1179/acb.2009.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Q, Sun M, Ma C, Lv H, Lu P, Wang Q, et al. Emphysematous pyelonephritis and cystitis in a patient with uremia and anuria. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e11272. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Momin UZ, Ahmed Z, Nabir S, Ahmed MN, Al Hilli S, Khanna M. Emphysematous prostatitis associated with emphysematous pyelonephritis and cystitis: a case report. J Clin Urol. 2017;10:286–289. doi: 10.1177/2051415816661655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Punatar C, Jadhav K, Kumar V, Joshi V, Sagade S. Neutrophil: lymphocyte ratio as a predictive factor for success of nephron-sparing procedures in patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis. Perm J. 2019;23:18–044. doi: 10.7812/TPP/18-044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]