Abstract

Objectives:

The current novel coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic presents a time-sensitive opportunity to rapidly enhance our knowledge about the impacts of public health crises on youth mental health, substance use, and well-being. This study examines youth mental health and substance use during the pandemic period.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was conducted with 622 youth participants across existing clinical and community cohorts. Using the National Institute of Mental Health-developed CRISIS tool and other measures, participants reported on the impacts of COVID-19 on their mental health, substance use, and other constructs.

Results:

Reports of prepandemic mental health compared to intrapandemic mental health show a statistically significant deterioration of mental health across clinical and community samples (P < 0.001), with greater deterioration in the community sample. A total of 68.4% of youth in the clinical sample and 39.9% in the community sample met screening criteria for an internalizing disorder. Substance use declined in both clinical and community samples (P < 0.001), although 23.2% of youth in the clinical sample and 3.0% in the community sample met screening criteria for a substance use disorder. Participants across samples report substantial mental health service disruptions (48.7% and 10.8%) and unmet support needs (44.1% and 16.2%). Participants report some positive impacts, are using a variety of coping strategies to manage their wellness, and shared a variety of ideas of strategies to support youth during the pandemic.

Conclusions:

Among youth with histories of mental health concerns, the pandemic context poses a significant risk for exacerbation of need. In addition, youth may experience the onset of new difficulties. We call on service planners to attend to youth mental health during COVID-19 by bolstering the accessibility of services. Moreover, there is an urgent need to engage young people as coresearchers to understand and address the impacts of the pandemic and the short, medium, and long terms.

Keywords: mental health, substance use, youth, adolescent, young adult, COVID-19, pandemics

Abstract

Objectifs :

La pandémie actuelle de du nouveau coronavirus de 2019 (COVID-19) offre une occasion critique d’améliorer rapidement nos connaissances au sujet des répercussions des crises de santé publique sur la santé mentale, l’utilisation de substances et le bien-être des adolescents. La présente étude examine la santé mentale et l’utilisation de substances durant la période de la pandémie.

Méthodes :

Un sondage transversal a été mené auprès de 622 adolescents participants issus de cohortes cliniques et communautaires existantes. À l’aide de l’instrument CRISIS mis au point par le NIMH et d’autres, mesures les participants ont fait état des répercussions de la COVID-19 sur leur santé mentale, leur utilisation de substances et d’autres concepts.

Résultats :

Les rapports sur la santé mentale pré-pandémique comparés à la santé mentale intra-pandémique révèlent une détérioration statistiquement significative de la santé mentale dans les échantillons cliniques et communautaires (p < ,001), la détérioration étant plus marquée dans l’échantillon communautaire. Un total de 68,4 % d’adolescents de l’échantillon clinique et 39,9 % de l’échantillon communautaire satisfaisaient aux critères de dépistage d’un trouble d’internalisation. L’utilisation de substances a diminué dans les deux échantillons, cliniques et communautaires (p < ,001), bien que 23,2 % des adolescents de l’échantillon clinique et 3,0 % de l’échantillon communautaire aient satisfait aux critères de dépistage d’un trouble d’utilisation de substances. Les participants des deux échantillons déclarent une interruption substantielle des services de santé mentale (48,7 % et 10,8 %) et des besoins de soutien non comblés (44,1 % et 16,2 %). Les participants mentionnent certains effets positifs, ils utilisent diverses stratégies d’adaptation pour gérer leur bien-être, et ils ont partagé diverses idées et stratégies pour soutenir les adolescents durant la pandémie.

Conclusions :

Chez les adolescents ayant des antécédents de problèmes de santé mentale, le contexte de la pandémie pose un risque significatif à l’exacerbation des besoins. En les adolescents peuvent voir survenir de nouvelles difficultés. Nous demandons aux planificateurs des services de prendre soin de la santé mentale des adolescents durant la COVID-19 en renforçant l’accessibilité des services. De plus, il y a un besoin urgent de recruter des jeunes gens comme co-chercheurs, pour comprendre et gérer les répercussions de la pandémie à court, à moyen et à long terme.

The COVID-19 crisis, declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, is affecting all segments of the population, around the world. Editorials and commentaries about mental health and COVID-19 have been rapidly emerging, raising concerns about psychological and mental health impacts and proposing interventions and strategies to address mental health during the pandemic.1–4

A rapid review of psychological impacts of previous quarantines5 highlights a number of mental health and well-being concerns. One study found high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in children affected by a previous pandemic,6 associated with isolation and quarantine. Another study found that hospital inpatients experienced high levels of concern about infection, changes in existing treatments, the lack of socialization, and reduced access to everyday resources.7 Research has related social support to better immune response8; this is concerning in a time of social distancing and infection. However, positive mental health impacts have also been found in a previous pandemic, such as increased sensitivity to friends’ and families’ needs and greater support.9

Research on the COVID-19 pandemic emerging from China suggests very high mental health impacts in a general population compared to nonpandemic times.10 Another Chinese study suggests that younger adults (<35 years) experience more severe mental health impacts than older adults.11 Building on these findings, rapid evidence is required to ensure that responses reflect the realities of the COVID-19 pandemic and the needs of diverse populations.

There is minimal research on mental health and substance use (MHSU) among youth during pandemics and during COVID-19 in particular, limiting our ability to meet the needs of youth. MHSU disorders affect about 1 in 5 youth in Canada.12 Adolescence and early adulthood are a peak age of onset for substance use, which can lead to substance use disorders.13,14 During public health crises, youth in general—and youth with pre-existing MHSU concerns in particular—are a vulnerable group.4,15 Youth are in the midst of achieving developmental milestones,16 which are adversely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, school completion, workforce engagement, and autonomous decision making.

This study aims to (1) rapidly enhance knowledge about the impacts of a public health crisis on youth MHSU and well-being; (2) provide information required to make real-time gains in reducing negative impacts and amplifying youth coping strategies for the current crisis; and (3) improve the readiness of decision makers for future pandemics.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among existing participant cohorts to rapidly understand how the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting youth MHSU, well-being, coping, and unmet needs. Participant cohorts were youth, defined as adolescents and young adults up to age 29.17

Participants

A total of 622 participants aged 14 to 28 (M = 20.6, standard deviation [SD] = 2.4) were recruited across 4 existing participant cohorts based at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto, Ontario: (1) The YouthCan IMPACT study,18 a clinical sample from an ongoing randomized controlled trial examining youth MHSU treatment pathways; (2) youth participating in research at the Youth Addiction and Concurrent Disorders Service,19 an outpatient clinical service; (3) a clinical sample of youth recruited across CAMH specialty clinics, participating in a longitudinal study evaluating mental health symptoms, cognition, and functioning; and (4) participants of the Research and Action for Teens longitudinal cohort study,20 a community sample of youth across the province of Ontario, Canada. A total of 2,025 youth across the 4 cohorts were invited to participate in the survey (804 clinical, 1221 community), yielding a response rate of 30.7% in a 3-week recruitment period.

Procedure

Potential participants were emailed a unique web link to an online survey in REDCap software.21 Consenters completed a 20-min self-report survey. Invitations were sent between April 8 and 29, 2020, beginning about 3 weeks after provincial declaration of a state of emergency due to COVID-19 and about 2 weeks after closure of nonessential services. Reminder emails were sent every 2 days. Participants received a CAD$15 honorarium. CAMH Research Ethics Board approved the study.

Measures

Demographic information included questions about participant’s age, gender, ethnic background, country of origin, and education and employment status.

CoRonavIruS Health Impact Survey

The Youth Self-Report Baseline version 0.1 of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-developed CoRonavIruS Health Impact Survey (CRISIS) tool was used to examine COVID-19 impacts on youth.22 The measure examines emotional and behavioral responses retrospectively at 3 months prior to the COVID-19 crisis and in the past 2 weeks, as well as service use, service disruption, and other constructs. For self-reported MHSU concerns, items about “worries” were combined into a mean mental health score, while items about substance use were combined into a substance use mean score. Given the recency of this measure, psychometrics are not available. However, our data show that the mental health score has a Cronbach α of .88 for 3-months prior to the COVID-19 crisis and .88 for current mental health. CRISIS scale mental health scores correlate with the number of items endorsed on the GAIN-Short Screener (GAIN-SS) internalizing disorder scale (described below) at r = .59, P < 0.0001, and with items endorsed on the GAIN-SS externalizing disorder scale at r = .40, P < 0.0001. CRISIS scale endorsements of substance use correlate with the GAIN-SS Substance Use scale at r = .51, P < 0.0001.

Brief COPE

Brief COPE (COPE-B) is a validated 28-item scale evaluating a range of coping strategies.23 Response options range from 0 (I haven’t been doing this at all) to 3 (I’ve been doing this a lot). Scores for the measure’s 14 scales were computed as the mean of the 2 items comprising each scale.

GAIN-SS

The GAIN-SS is a 20-item self-report screener examining internalizing, externalizing and substance use disorders, and crime/ violence issues.24 Items are scored from 0 to 3, with a score of 3 indicating that the symptom has been present in the past month. According to scale norms, 3 or more past-month endorsements suggest a high likelihood of meeting diagnostic criteria or requiring services in that domain.24,25 Past-month endorsements reflect symptoms during the early pandemic period. The GAIN-SS has 91% sensitivity and 90% specificity at the threshold of 3 or more items.

Custom-designed questions

Several custom questions were developed in consultation with our Youth Engagement Initiative.26 Our youth team raised concerns about living situation disruptions; school, work, and service disruptions; finances; family members or themselves becoming ill; limited access to substances and harm-reduction supplies; and the risk of relapse or loss of therapeutic gains. However, they also pointed to the resilience of youth. We therefore designed custom questions on youth strategies to keep well, as well as various open-ended questions. We also asked participants for their ideas for supporting youth during COVID-19.

Analyses

Data were analyzed descriptively using frequencies, with comparisons of clinical and community samples using chi-square and independent sample t-tests as appropriate, with Cohen d and phi effect sizes. Missing data at the variable level were minimal; mean scores were used when possible to reduce the impact of missing data. Percentage scores were computed based on the total N that completed that survey section. Retrospective reports of MHSU prior to COVID-19 were compared with scores for the past 2 weeks, using repeated measures mixed analysis of variances (ANOVAs). For the COPE-B, clinical and community samples were compared using independent sample t-tests (with Levine corrections where necessary). Open-ended responses were analyzed qualitatively by categorizing them into the prevailing response sets.

Results

The clinical sample consisted of 276 (44.4%) youth, and the community sample included 346 (55.6%) youth. The mean age of the clinical sample was 20.2 (SD = 3.2), while the mean age of the community sample was 21.0 (SD = 1.4). This was a statistically significant difference, t(355) = 3.437, P = 0.0007, d = .32 (Table 1). From a univariate perspective, the majority of participants in both samples identified as a girl/woman, were Caucasian, were Canada-born and English-speaking, and were students. The majority lived in family homes with other people. While the majority of participants in both samples were employed prior to the COVID-19 crisis, only a minority were employed at the time of the survey, which represents a significant decline (clinical: χ 2(1) = 37.737, P < 0.0001, ϕ = .37; community: χ 2(1) = 61.942, P < 0.0001, ϕ = .43).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants, for Clinical and Community Samples.

| Demographic characteristic | Clinical sample | Community sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Age | ||||

| <18 | 59 | 21.5 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 to 22 | 147 | 53.6 | 304 | 88.9 |

| 23 to 27 | 68 | 24.8 | 38 | 11.1 |

| Gender | ||||

| Man/boy | 75 | 27.2 | 129 | 37.3 |

| Woman/girl | 179 | 64.9 | 210 | 60.7 |

| Another gender | 22 | 8.0 | 7 | 2.0 |

| Ethnic origin/background | ||||

| Caucasian | 173 | 63.1 | 207 | 59.8 |

| Asian (East and Southeast) | 17 | 6.2 | 48 | 13.9 |

| South Asian | 12 | 4.4 | 35 | 10.1 |

| Black (African, Caribbean, North American) | 9 | 3.3 | 19 | 5.5 |

| Multiple | 35 | 12.8 | 13 | 3.8 |

| Indigenous | 2 | 0.7 | 5 | 1.4 |

| Another background | 26 | 9.5 | 19 | 5.5 |

| Born in Canada | 239 | 86.9 | 306 | 88.4 |

| First language English | 257 | 93.5 | 308 | 89.0 |

| Student | 172 | 62.5 | 223 | 64.5 |

| Highest level of education | ||||

| Less than high school | 94 | 34.3 | 13 | 3.8 |

| High school diploma | 61 | 22.3 | 79 | 22.9 |

| Some college, university, or technical school | 82 | 29.9 | 146 | 42.3 |

| Postsecondary diploma or certification | 37 | 13.5 | 107 | 31.0 |

| Employed before COVID-19 | 145 | 52.7 | 240 | 69.8 |

| Employed now | 56 | 20.5 | 123 | 35.8 |

| Housing | ||||

| Own home/apartment | 34 | 12.3 | 49 | 14.2 |

| With parents/family home, relatives | 188 | 68.3 | 260 | 75.1 |

| Share with friends/peers | 19 | 6.9 | 12 | 3.5 |

| With partner/spouse | 18 | 6.5 | 16 | 4.6 |

| Boarding house, shelter, supportive housing | 11 | 4.0 | 7 | 2.0 |

| Other | 5 | 1.8 | 2 | 0.6 |

| Number of other people in home | ||||

| Alone | 11 | 4.2 | 4 | 1.2 |

| 1 to 2 | 112 | 43.2 | 116 | 34.3 |

| 3 to 4 | 101 | 39.0 | 170 | 50.3 |

| 5 or more | 35 | 13.5 | 48 | 14.2 |

Mental Health

On a scale of 1 to 5, the clinical sample rated mental health symptoms at an average of 3.06 prior to COVID-19 (SD = .71) and 3.48 in the past 2 weeks (SD = .80). In the community sample, these scores were 2.49 (SD = .72) and 3.14 (SD = .77), respectively. A repeated-measures mixed ANOVA shows a significant main effect of time, showing that mental health has deteriorated, F(1, 617) = 271.280, P < 0.0001, partial η2 = .31. A significant group effect, F(1, 617) = 80.189, P < 0.0001, partial η2 = .12, shows that mental health concerns were higher in the clinical sample. A significant group × time interaction, F(1, 617) = 12.074, P = 0.0005, partial η2 = .02, shows that the deterioration effect associated with time was stronger in the community sample than in the clinical sample. When asked to specify their mental health symptom of greatest concern in an open-ended question, in the clinical sample, 71 (25.7%) youth specified depression or sadness, 47 (17.0%) anxiety, 16 (5.8%) suicide or self-harm, and 13 (4.7%) substance use. In the community sample, these specified concerns were 46 (13.3%) youth for depression, 37 (10.7%) for anxiety, 9 (2.6%) for suicidal thoughts or urges to self-harm, and 0 for substance use.

GAIN-SS responses demonstrate the past-month threshold for a high likelihood of a diagnosis in the internalizing disorder domain was met by 182 (68.4%) youth in the clinical sample and 135 (39.9%) youth in the community sample, χ2(1) = 48.415, P < 0.0001, ϕ = .28. For externalizing disorders, these rates were 107 (40.2%) and 57 (16.9%), respectively, χ2(1) = 41.072, P < 0.0001, ϕ = .26.

Substance Use

On a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (regularly), the clinical sample rated substance use at an average of 1.79 prior to COVID-19 (SD = .63) and 1.72 in the past 2 weeks (SD = .65). In the community sample, these rates were 1.39 (SD = .44) prior to COVID-19 and 1.32 (SD = .44) in the past 2 weeks. A repeated-measures mixed ANOVA reveals a significant time effect, F(1,616) = 27.484, P < 0.0001, partial η2 = .04, showing a decrease over time. The group effect was also statistically significant, F(1, 616) = 91.847, P < 0.0001, partial η2 = .13, showing that substance use was higher in the clinical sample. The interaction effect was not significant, F(1, 616) = 0.001, P = 992, partial η2 < 0.001, showing that the relationship between time and substance use was consistent across samples.

On the GAIN-SS, 62 (23.2%) youth in the clinical sample and 10 (3.0%) youth in the community sample met high likelihood criteria for a substance use disorder, χ2(1) = 58.412, P < 0.0001, ϕ = .31.

Service Disruption and Unmet Need

Participants reported service disruptions in terms of mental health services (clinical: 50.0%, community: 10.9%, χ2(1) = 114.482, P < 0.0001, ϕ = .43) and other health-related services (clinical: 16.2%, community: 8.5%, χ2(1) = 8.490, P = 0.0036, ϕ = .12). Other social and recreational services had also been disrupted (clinical: 46.3%, community: 52.8%, χ2(1) = 2.528, P = .112, ϕ = .06). Many youth reported needing MHSU services that they were not receiving at this time (clinical: 45.4%, community: 16.5%); χ2(1) = 59.916, P < 0.0001, ϕ = .32. When asked to specify the kinds of supports needed but unavailable, 72 participants in the clinical sample (26.1%) specified therapy/counseling; among them, 14 (19.4%) specified that this should be in person. In addition, 14 (5.1%) specified substance use services, and 14 (5.1%) specified psychiatric services. In the community sample, 35 (10.1%) specified therapy or counseling; of which 4 (11.4%) of them specified “in-person,” 7 (2.0%) psychiatry, and 0 specified substance use services. A few participants mentioned needing “someone to talk to.”

Areas of Concern During COVID-19

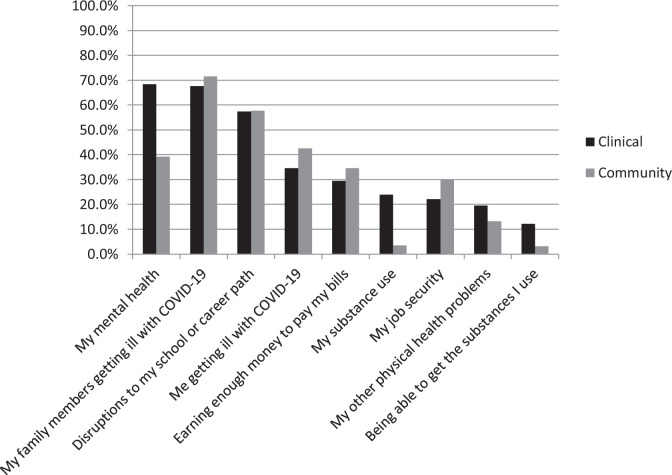

More than half of youth across samples were concerned about a family member falling ill and disruptions to their school or career path (Figure 1). Concerns about mental health were frequent in both samples, as were concerns about falling ill and financial or job concerns. Almost a quarter of youth in the clinical sample were concerned about their substance use, despite the overall reduction observed in substance use. Significant group differences emerged for mental health concerns, clinical: 68.4%, community: 39.3%, χ2(1) = 51.303, P < 0.0001, ϕ = .29; substance use concerns, clinical: 23.9%, community: 3.5%, χ2(1) = 57.207, P < 0.0001, ϕ = .31; being able to access substances, clinical: 12.1%, community: 3.2%, χ2(1) = 18.015, P = 0.0001, ϕ = .17; themselves falling ill with COVID-19, clinical: 34.6%, community: 42.5%, χ2(1) = 4.034, P = 0.0446, ϕ = .08; other physical health problems, clinical: 19.5%, community: 13.2%, χ2(1) = 4.455, P = 0.0348, ϕ = .09; and job security, clinical: 22.1%, community: 29.9%, χ2(1) = 4.799, P = 0.0285, ϕ = .09. Additional concerns specified consistently across samples in an open-ended field focused on education and employment, recreational activities, social activities, financial and economic impacts, and the pandemic’s duration.

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants reporting various areas of concern in relation to the COVID-19 crisis, among clinical and community samples.

Positive Impacts

Almost half of the clinical sample (47.3%) and 40.3% of the community sample reported that COVID-19 had had “a few” or “some” positive impacts on their lives, χ2(1) = 3.008, P = 0.083, ϕ = .07. In an open-ended question, many participants across samples reported that they were spending more time with family and were experiencing improved social relationships. More free time, time for hobbies and exercise, rest and relaxation, and sleep were also frequently reported. Some youth expressed benefits related finances, such as gaining more hours at work or receiving pay increases or saving more money. Some youth in both samples reported improved mental health as well as greater self-reflection and self-care. In the clinical sample, some reported reduced substance use and reduced school or work anxiety and stress.

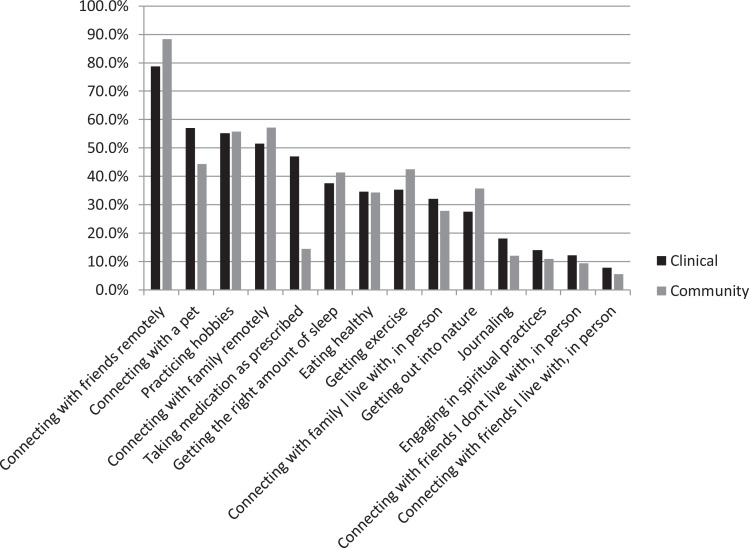

Methods of Keeping Well

When asked what they were doing to keep well (Figure 2), the most frequently reported strategy was connecting with friends remotely. Also highly endorsed were connecting with a pet, practicing hobbies, and connecting with family remotely. Few youth reported connecting in person with people they do not live with. Significantly higher rates were observed in the clinical population in terms of taking medication as prescribed, clinical: 47.1%, community: 14.4%, χ2(1) = 78.729, P < 0.0001, ϕ = .36; connecting with a pet, clinical: 57.0%, community: 44.3%, χ2(1) = 9.768, P = 0.0018, ϕ = .13; and journaling, clinical: 18.0%, community: 12.0%, χ2(1) = 4.336, P = 0.037, ϕ = .08. Community participants were significantly more likely to be connecting with friends remotely, clinical: 78.7%, community: 88.3%, χ2(1) = 10.368, P = 0.0013, ϕ = .13, and getting out into nature, clinical: 27.6%, community: 35.8%, χ2(1) = 4.669, P = 0.0307, ϕ = .09.

Figure 2.

Percentage of participants reporting various strategies engaged in to keep well during the COVID-19 crisis, for clinical and community samples.

Coping Styles

The most highly endorsed coping styles across samples were acceptance and self-distraction (Table 2). Many youth were also using positive reframing, active coping, and planning. Participants in the clinical sample were significantly more likely to use humor, venting, behavioral disengagement, self-blame, denial, and substance use.

Table 2.

Average Coping Styles for COPE-B Scales Endorsed by Clinical and Community Populations, with Independent Sample t-Tests and Effect Sizes.

| Coping style | Clinical sample | Community sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | P | d | |

| Active coping | 1.23 | 0.89 | 1.29 | 0.81 | 0.822 | 0.412 | −0.07 |

| Planning | 1.23 | 0.92 | 1.20 | 0.84 | 0.417 | 0.677 | 0.03 |

| Positive reframing | 1.33 | 0.89 | 1.28 | 0.88 | 0.756 | 0.450 | 0.06 |

| Acceptance | 1.95 | 0.79 | 1.89 | 0.82 | 1.029 | 0.304 | 0.08 |

| Humor | 1.42 | 0.92 | 1.15 | 0.92 | 3.538 | <0.001 | 0.31 |

| Religion | 0.57 | 0.88 | 0.58 | 0.86 | 0.134 | 0.893 | −0.01 |

| Instrumental support | 1.11 | 0.87 | 0.98 | 0.85 | 1.755 | 0.080 | 0.15 |

| Self-distraction | 1.92 | 0.75 | 1.77 | 0.81 | 2.256 | 0.024 | 0.19 |

| Denial | 0.54 | 0.81 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 2.431 | 0.015 | 0.20 |

| Venting | 1.25 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.74 | 5.441 | <0.001 | 0.45 |

| Substance use | 1.17 | 1.23 | 0.44 | 0.81 | 8.390 | <0.001 | 0.70 |

| Behavioral disengagement | 1.06 | 0.88 | 0.53 | 0.74 | 7.895 | <0.001 | 0.65 |

| Self-blame | 1.43 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 5.840 | <0.001 | 0.48 |

| Emotional support | 1.35 | 0.91 | 1.19 | 0.86 | 2.205 | 0.028 | 0.18 |

Primary Source of Information

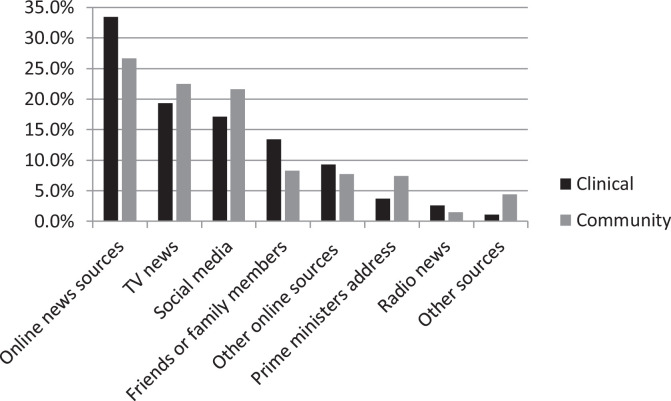

When asked to identify their primary source of information about COVID-19 (Figure 3), the majority in both clinical and community samples identified online sources: online news (33.5% and 26.6%, respectively), social media (17.1% and 21.6%), and other (9.3% and 7.7%). Many also identified TV news sources (clinical: 19.3%, community: 22.5%) and the Canada’s Prime Minister’s daily televised address: 3.7% and 7.4%.

Figure 3.

Primary source of information about COVID-19 among clinical and community samples.

Supporting Youth During the COVID-19 Crisis

Participants provided a variety of support recommendations. Participants emphasized the need for more MHSU support, through free remote counseling options and online support groups. Participants recommended attending to the unique financial situations of youth, that is, providing rent support, student loan and tuition relief, and government financial supports for students. They indicated that youth would benefit from ideas about activities to stay connected and entertained, emphasizing hobby development and meaningful activities. Participants were interested in being able to access high-quality information about COVID-19 and MHSU supports available to help them. They wanted more positive and encouraging media messaging. They also wanted opportunities to develop a sense of meaning during these times. A few pointed out that not all youth have internet access, which is a substantial barrier. These recommendations were consistent across samples.

Discussion

This study directly gathered information from youth about their MHSU and well-being needs and pandemic-related experiences during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. Results show that many youth are concerned about their mental health, perceive their mental health to have deteriorated since before the pandemic, and likely meet criteria for a mental health diagnosis. Notably, in the community sample, current symptom levels surpassed the retrospective prepandemic levels of the clinical sample, and more than a third of the sample were likely to meet criteria for a mental health diagnosis. While substance use appears to have declined as a whole, perhaps due to social changes associated with physical distancing, a subset of youth reported using substances to cope and likely meet criteria for a substance use disorder. Many youth are concerned about a loved one or themselves becoming ill with COVID-19, as well as impacts on their school and career trajectories. However, some youth identified improved mental health and self-care. Youth want access to reliable information about COVID-19 with positive, encouraging framing, primarily online. They also want more mental health supports, financial supports, and ideas of activities to keep well, engaged, and busy.

The mental health sector was not prepared for the current pandemic, and “disaster medicine” has rapidly moved from a niche field to a necessary core skill set. Despite an increase in mental health concerns, many youth reported service disruptions and unmet need. A recent study from China, in an adult clinical population, found that about one-fifth to one-quarter of patients receiving mental health services could not get needed psychiatric services, leading many to make medication adjustments without psychiatric support.27 It is critically important that attention is paid to mental health during public health crises to minimize immediate impacts and prevent long-term repercussions.5

For youth, service adaptations and pandemic response strategies must occur through a developmental lens. Many of the challenges and coping strategies identified through this study reflect developmental tasks and milestones for youth.16 These findings provide information that service planners can use to bolster youth services. For example, secure e-mental health solutions are required, providing easily accessible services28 for youth who are already connected with services, but also for those who have not previously been connected. An emphasis on creating robust developmentally appropriate engagement strategies will be required to engage first-time help-seekers through remote platforms. For a subset of youth, in-person services may continue to be necessary and should be considered “essential,” especially for young people experiencing suicide and self-harm related concerns.

From a brief solution-oriented approach,29,30 the coping mechanisms and positive impacts that may be helping other youth could be a starting point for discussions with youth seeking services due to pandemic-related concerns. To provide youth with information about COVID-19, mental health, and coping, it is important to create accessible, accurate, reliable online materials.

The United Kingdom has issued a call for action on COVID-19 mental health research.4 Longitudinal monitoring will support service planning, as youth MHSU service needs may evolve over the course of the pandemic and recovery period. This monitoring must be informed by developmental perspectives and by youth themselves. Rapid-response research can be challenging but is being substantially facilitated by a rapidly mobilizing international research community, including the NIMH developers of the CRISIS survey,22 the ability to leverage existing participant cohorts, and responsive Research Ethics Boards, all of which made this study possible on a short timeline.

Limitations

This is a cross-sectional survey; prepandemic MHSU was retrospectively reported and may have been affected by recall bias. Longitudinal research is required to understand how youth experiences evolve over time. The sample size was limited. The youth most negatively affected by COVID-19 may have been less likely—or more likely—to complete the survey. While participants may not be representative of Ontario youth, this represents a substantial sample for a rapid, time-sensitive survey. Future equity-focused research is needed with larger samples to understand differential population subgroup impacts from a diversity and equity perspective. The clinical sample consisted of youth seeking services at academic hospitals in an urban center; these results may not generalize to clinical samples seeking care in the community or rural areas.

Conclusions

Youth have many concerns during COVID-19, and they perceive substantial effects on their mental health; their mental health service needs are not currently being met. Despite this, youth have many positive coping strategies and valuable ideas for increasing supports. Service planners are encouraged to apply these findings to bolster supports for youth in creative ways during this critical time, by providing accessible MHSU services remotely; for some youth, these may need to be offered in person, respecting social/physical distancing requirements. Services should emphasize positive coping strategies in line with the issues raised by youth. Service providers should also work to ensure that accurate, reliable information is available to youth.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Margaret and Wallace McCain Centre for Child, Youth and Family Mental Health. Participants were drawn from cohorts funded by the Ontario SPOR Support Unit, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, University of Toronto Miner’s Lamp Innovation Fund in Prevention and Early Detection of Severe Mental Illness, Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health, and Innovative Medicines (formerly Rx and D Research Foundation). The funders had no role in the research.

ORCID iDs: Lisa D. Hawke, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1108-9453

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1108-9453

Kristin Cleverley, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2822-2129

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2822-2129

Darren Courtney, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1491-0972

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1491-0972

References

- 1. Duan L, Zhu G. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):300–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yao H, Chen JH, Xu YF. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ho CS, Chee CY, Ho RC. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19: beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2020;49(3):1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sprang G, Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7(1):105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003;168(10):1245–1251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006;29(4):377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lau JT, Yang X, Tsui HY, Pang E, Wing YK. Positive mental health-related impacts of the SARS epidemic on the general public in Hong Kong and their associations with other negative impacts. J Infect. 2006;53(2):114–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boyle MH, Georgiades K. Disorders of childhood and adolescence In: Cairney J, Streiner D, editors. Mental disorders in Canada: An epidemiological perspective. Toronto (ON): University of Toronto Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boak A, Elton-Marshall T, Mann RE, Hamilton HA. Drug use among Ontario students, 1977-2019: Detailed findings from the Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS). Toronto (ON): Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Young SE, Corley RP, Stallings MC, Rhee SH, Crowley TJ, Hewitt JK. Substance use, abuse and dependence in adolescence: prevalence, symptom profiles and correlates. Drug and Alcohol Depend. 2002;68(3):309–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perrin PC, McCabe OL, Everly GS, Jr, Links JM. Preparing for an influenza pandemic: mental health considerations. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24(3):223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Statistics Canada. A portrait of Canadian youth: March 2019 updates. 2019. [accessed 2020 May 15]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-631-x/11-631-x2019003-eng.htm

- 18. Henderson JL, Cheung A, Cleverley K, et al. Integrated collaborative care teams to enhance service delivery to youth with mental health and substance use challenges: protocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e014080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hawke LD, Koyama E, Henderson J. Cannabis use, other substance use, and co-occurring mental health concerns among youth presenting for substance use treatment services: sex and age differences. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;91:12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Henderson JL, Brownlie EB, McMain S, et al. Enhancing prevention and intervention for youth concurrent mental health and substance use disorders: the research and action for teens study. Early Inter Psychiatry. 2019;13(1):110–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Merikangas K, Milham M, Stringaris A, Bromet E, Colcombe S, Zipunnikov V. The corona virus Health Impact Survey (CRISIS). 2020. [accessed 2020 May 15]. https://github.com/nimh-mbdu/CRISIS

- 23. Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’ too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(1):92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dennis ML, Chan YF, Funk RR. Development and validation of the GAIN Short Screener (GSS) for internalizing, externalizing and substance use disorders and crime/violence problems among adolescents and adults. Am J Addict. 2006;15(Suppl 1):80–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dennis ML, Feeney T, Hanes Stevens LV, Bedoya L. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs–Short Screener (GAIN-SS): Administration and Scoring Manual Version 2.0.3. Bloomington (IL): Chestnut Health Systems; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Heffernan OS, Herzog TM, Schiralli JE, Hawke LD, Chaim G, Henderson JL. Implementation of a youth-adult partnership model in youth mental health systems research: challenges and successes. Health Expect. 2017;20(6):1183–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhou J, Liu L, Xue P, Yang X. Mental health response to COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am J Psych. 2020;177(7):574–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wind TR, Rijkeboer M, Andersson G, Riper H. The COVID-19 pandemic: the ‘black swan’ for mental health care and a turning point for e-health. Internet Inter. 2020;20:100317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lethem J. Brief solution focused therapy. Child Adolescent Mental Health. 2002;7(4):189–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gingerich WJ, Peterson LT. Effectiveness of solution-focused brief therapy. Res Soc Work Pract. 2013;23(3):266–283. [Google Scholar]