PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

For patients with unexplained altered consciousness, the presence of the typical skin lesions may indicate Kambó poisoning.

We report on the potential for severe neurologic effects from the use of Kambó (also known as Sapo). Kambó is the term for the secretions obtained from the frog genus Phyllomedusa bicolor, which is found in the Amazon basin and other surrounding areas.1 The secretions, which are a protective mechanism to deter predators, are increasingly being used in alternative medicine rituals in both rural and urban locations in South American countries such as Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, and Chile, and additionally in Europe.1–3 The ritual consists of making various types of skin lesions with a burning stick and applying the secretions from P bicolor to the fresh wounds (figure). Typically, for women, these are located on the legs, whereas for men, they are on the arm or chest.

Figure. The sites where Kambó was inoculated on the patient's left leg.

A 41-year-old woman sought treatment for depression with Kambó from a shaman in the north of Chile. She did not have any other relevant medical history and was not taking any medications (and specifically no monoamine oxidase [MAO] inhibitors). The shaman made wounds on her left leg with burning sticks (figure) to which the Kambó was applied. A few minutes after this application, she became unresponsive, with extreme hypotonia of the limbs and hypoventilation. Emergency medical services intubated her at home, and she was hospitalized, requiring mechanical ventilation for 3 days. No further sedatives or other medications were administered initially. After she recovered consciousness, she developed visual (animals and people) and auditory hallucinations and occasional generalized seizures. She was given valproic acid 500 mg twice a day as an anticonvulsant but no antipsychotics or sedatives. Brain imaging with CT and MRI were normal, as was EEG. On day 2, she developed rhabdomyolysis and renal failure, which resolved with hydration over the next few days. By 7 days after presentation, she had fully recovered and was discharged.

On outpatient evaluation 15 days later, she was fully alert, with mild deficits in attention, but was otherwise neurologically intact. Follow-up brain MRI and EEG were normal. Valproic acid was gradually tapered off without further seizures.

Discussion

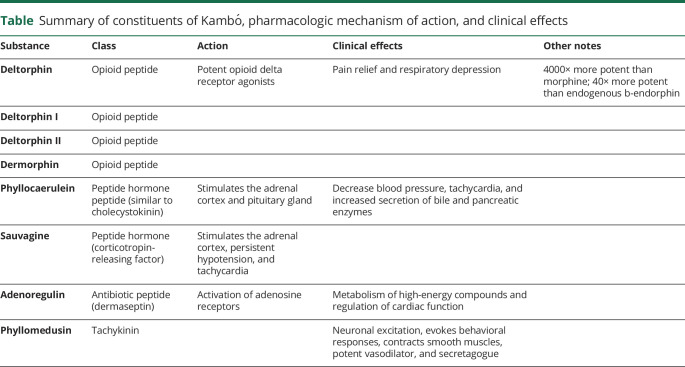

The skin of the neotropical and South American frogs contains large amounts of a wide range of biologically active peptides that are either identical or highly homologous to hormones, neurotransmitters, and other bioactive peptides of higher vertebrates4 (table). More than a hundred active peptides have been isolated from the skins of these frogs to date.2–4 The mechanisms of action of the P bicolor secretions are not completely understood; a number of cytotoxic effects on different cell types have been identified.5,6 In addition, some of the toxins dilate blood vessels and increase the permeability of the blood-brain barrier.5

Table.

Summary of constituents of Kambó, pharmacologic mechanism of action, and clinical effects

The use of the Kambó secretions has become increasingly popular in cleansing rituals during which intense vomiting is induced. Claims of medicinal effects have not been supported by medical evidence.3 Other alternative medicines that are becoming more widely used for this purpose include Ayahuasca and Jurema-Preta from Central/South America and Iboga from Western Central Africa. Experienced shamans typically (and traditionally) oversee the rituals; however, this is no longer always the case. These medicines are contraindicated specifically if the patient is on MAO inhibitors because of the increased risk of side effects.

The shamanic ritual was initially used to improve luck in hunting by the Matses Indians of the Northern Peru, but has subsequently become used as a purification rite.5,6 The drug causes the prompt appearance of violent peripheral gastrointestinal (nausea and vomiting) and cardiovascular effects, followed by marked central effects (sensation of increased physical strength, heightening of senses, resistance to hunger and thirst, and increased capacity to face stressful situations).5,6 The period of intense illness (typically <1 hour) is followed by a state of listlessness and sleep lasting from 1 to several days. Carneiro1 reported that vivid hallucinations occur, although this is not supported by other observations.1 The intensity of human reactions to the frog secretion is doubtless dose dependent.1

There are few published reports of Kambó toxicity2,3,7; 1 woman is reported to have died in a major hospital in Chile following Kambó use. Clinicians must be aware of the increasing use of this hazardous substance and its clinical manifestations, especially in light of the fact that Kambó secretions can now be readily obtained over the internet. In the unconscious patient, recognition of these typical lesions (on the legs for women and the left arm or chest for men) indicates the diagnosis of Kambó poisoning.

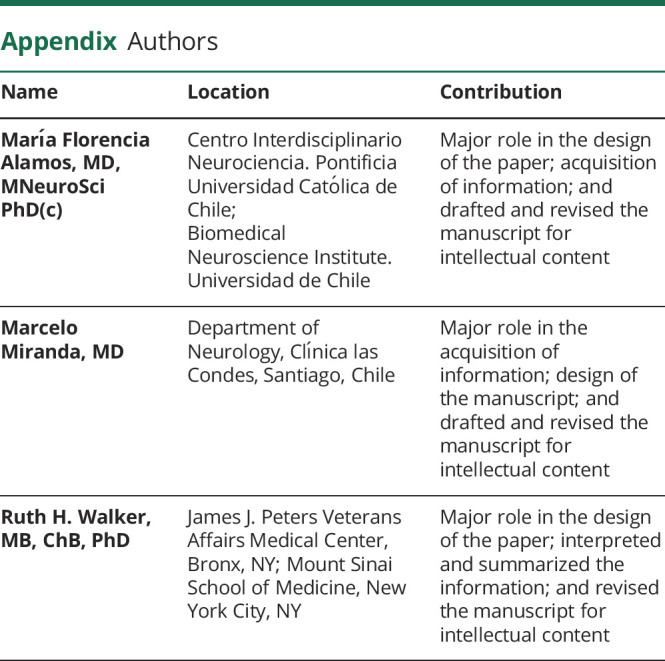

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

M.F. Alamos reports no disclosures. R.H. Walker has received honoraria from Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc. and the International Parkinson Disease and Movement Disorder Society and consulting fees from Advance Medical Opinion and Teladoc. M. Miranda reports no disclosures. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Daly JW, Caceres J, Moni RW, et al. . Frog secretions and hunting magic in the upper Amazon: identification of a peptide that interacts with an adenosine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992;89:10960–10963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Den Brave PS, Bruins E, Bronkhorst MW. Phyllomedusa bicolor skin secretion and the Kambô ritual. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 2014;20:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pogorzelska J, Lapinski W. Toxic hepatitis caused by the excretions of the Phyllomedusa bicolor frog – a case report. Clin Exp Hepatol 2017;3:33–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lacombe C, Cifuentes-Diaz C, Dunia I, Auber-Thomay M, Nicolas P, Amiche M. Peptide secretion in the cutaneous glands of South American tree frog Phyllomedusa bicolor: an ultrastructural study. Eur J Cell Biol 2000;79:631–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erspamer V, Melchiorri P, Falconieri-Erspamer G, Negri L, Deltorphins. A family of naturally occurring peptides with high affinity and selectivity for delta opioid binding site. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1989;86:5188–5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erspamer V, Erspamer GF, Severini C, et al. . Pharmacological studies of ‘sapo’ from the frog Phyllomedusa bicolor skin: a drug used by the Peruvian Matses indians in shamanic hunting practices. Toxicon 1993;31:1099–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li K, Horng H, Lynch K, Smollin CG. Prolonged toxicity from Kambo cleansing ritual. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2018,56:1165–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]