Highlights

-

•

Food waste (FW) generation and the need for policy in Vietnam are investigated.

-

•

Each residence produced 0.29 kg p−1 d−1, accounting for 31.7 % of total waste.

-

•

Approximately 38.8 % of families discharged FW as well as municipal waste.

-

•

Prioritization of strategy, strict rules, and recycling to animal feed is highlighted.

-

•

FW will be crucial for gaining a noticeable improvement in Vietnam’s waste management.

Keywords: Food waste, Animal feed, Fertilizer, Biorefinery, Waste management

Abstract

Food waste (FW) is more harmful than previously imagined. A large amount of Vietnam’s FW ends up in landfills, only 20 % of which are sanitary. This causes significant environmental problems such as greenhouse gas emissions, high carbon footprint, leachate, and landfill-related conflicts. The FW from Vietnam’s urban areas is 0.29 kg⸳p−1⸳d−1, accounting for 31.7 % of total waste. 38.81 % of families discharge FW which, along with municipal waste, corresponds to 4,429.21 ton⸳d−1 for the entire country. For FW collection, under transportation and treatment heads, 80,416.95 $⸳d−1 and 74,605.57 $⸳d−1 were spent, respectively. An analysis of Vietnam’s national strategy for the integrated management of solid waste indicates that the amount of attention and concern currently given to FW issues is not adequate to address them. To resolve FW issues, Vietnam needs to be more proactive regarding solutions and efforts, in addition to implementing strict regulations. These include the setting of national goals under the priority of national strategy, strict regulations, stakeholder engagement, FW recycling to animal feed, biorefinery, and awareness-raising campaigns.

1. Introduction

Solid waste is regarded as a resource and its recycling and reuse are priorities. In 2009 Vietnam issued a legal document called the National Strategy on Integrated Management of Solid Waste, and a revised version in 2018, which affirmed the view that waste must be considered as a resource and encouraged waste to be used for raw materials, fuels, and environment-friendly products. The environmental-friendly materials or products from waste include compost and animal feed from food waste, recyclable construction materials from fly ash, and biogas from domestic and animal waste. As the previous strategic goal of 90 % of municipal solid waste (MSW) being recovered for reuse, recycling or energy recovery by 2020 was not met, and the fact that Vietnam has seen an 8.4 % rise in MSW with only a rate of 14 % annual recycling [1], it is likely the current strategy of solid waste management in Vietnam is likely to fail. In addition, it also shows that sustainable waste management for recycling, reuse, and energy recovery is facing many challenges.

Nationally, more attention is usually given to plastic waste rather than organic waste, especially food waste (FW). However, a report by Zero Waste Scotland [2] revealed that FW contributes to global warming three times more than plastic waste. Furthermore, FW contributes half the weight of Vietnam’s landfills that are not appropriately operated [3]. In addition, landfills polluted with among other things, FW, are one of the main causes of increasing landfill-related conflicts. FW has not yet become the subject of municipal, provincial, or national policy discussions, and this lapse creates grave consequences for the environment and public health in Vietnam.

Several previous investigations have reported the status of and problems associated with FW in Vietnam. Thi et al. [4] reported that FW accounts for 60 % of MSW in Vietnam, and around 83%–88.9% of FW from Ho Chi Minh City was disposed of in landfills [5]. A study of FW in Hanoi by Cesaro et al. [6] concluded that informal forms of livestock recycling, such as food scraps collected by local farmers to feed pigs, chickens, and fish were under pressure due to metropolization. However, the policy, recycling strategy, technology, and generation rate (amount created per household) of Vietnam’s FW has not yet been fully explored. Policy and data gaps regarding FW need to be filled to promote and support improved waste management.

This study aims to clarify the need for handling FW and calls for a national plan and introduction of biotechnology solutions to improve the status of FW handling. National policy recommendations are made, supported by FW investigation data and a contextual analysis using data from other countries. Contextual analysis is a holistic point of a context and the whole circumstances in which objects occur and operate

2. Food waste status and related issues

2.1. Policies for solid and food waste

To support and fulfill the commitment to solid waste management, Vietnam launched the National Strategy on Integrated Management of Solid Waste in 2009 and a revised version in 2018. Regarding MSW, collection rate, landfill, plastic waste, waste classification at the source, recycling facilities, and dumping rate are highlighted in the strategy. The strategy established the following targets for 2025 regarding MSW:

-

•

90 % of the total MSW will be collected and treated to meet environmental protection requirements, including enhanced recycling, reuse, and energy recovery.

-

•

All commercial centers and supermarkets are to switch to providing eco-friendly plastic bags in place of conventional plastic bags.

-

•

More than 85 % of municipalities should have recycling facilities suitable for classified household waste.

-

•

MSW treated by the landfill method should account for less than 30 % of collected waste.

-

•

80 % of agricultural byproducts must be reused.

-

•

New waste treatment facilities must ensure that dumping rates do not exceed 20 %.

Other aspects such as raising public awareness, financial sources, and involvement and participation of stakeholders are not specified in the policy. Key political commitments help to guide policy and allocate resources for sound environmental and biotechnology policies at the national and local levels.

An increasingly popular and effective approach for waste management is zero waste, which focuses on maximizing recycling and reuse, minimizing waste created, and reducing consumption [7]. The Scottish Government has incorporated zero waste principles into their national policy. This program was developed with the aim of reducing waste to landfills and increasing the reduction, reuse, and recycling of waste. Through an organization (Zero Waste Scotland), several schemes have been successfully executed, such as transforming attitudes toward food waste, implementing a carrier bag charge, developing partnerships with the reuse sector, delivering the circular economy and supporting the low carbon infrastructure transition program, and developing the Scottish household recycling charter [2].

To achieve the goal of sustainable waste management, the involvement and participation of all stakeholders, such as waste generators and processors, nonprofit organizations, formal and informal agencies, government institutions, and financing institutions, are vital to the decision-making process for waste strategy and policies. Public participation plays an important role in waste management; for example, the proper storage of trash, separation at the source, and more reuse of waste materials [8]. However, the public is only engaged to a very limited degree in the process of preparing waste policies. Similar to other developing countries [9], Vietnam's policy-making process remains a top-down approach, in which the municipal authorities play the greatest role in the progression of waste management.

The typical forms of stakeholder participation in the waste policymaking process in Vietnam are consultation meetings or feedback documents. The Ministry and Department of Natural Resources and Environment are the leads of consultation meetings for national and local policies, respectively. Consultations are generally held several months to years before the planned start date of the policy, depending on the type of policy. For example, for the national policy of solid waste, consultation meetings were held approximately 12 months before the planned time the policy was to be enacted. If a consultation meeting is not organized, a draft of the waste policy is sent to local administrative agencies and they produce a feedback document.

In addition, the draft document is sent to local government agencies for feedback. Governmental organizations, local governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and social organizations are the main stakeholders who participate in preparing waste policy. The participation of residents and the private sector in this process is limited and the exact role of stakeholder participation in the waste policy preparation process is not fully clear due to a lack of information and clarity. Policies formulated by the government to advance waste recycling or recovery without public participation may be in vain [10]. Although stakeholder input is an important factor in increasing the effectiveness and sustainability of policy, there is no perfect, one-size-fits-all model for developing policies or guidelines, or defining stakeholder roles in any or all stages of the policymaking process [11]. In addition to a national strategy, Vietnam's provinces have their own policies regarding waste management. However, provincial waste policies focus mainly on fees for waste collection and treatment. Policies for waste and recycling is the same across provinces.

National policies to address FW issues normally focus on raising awareness, market-based instruments, technologies, trading schemes, and public-level communication. The United Nations (UN) has set a global goal of reducing FW at retail and consumer levels (per capita) by half by 2030 [12]. Strict policies, awareness-raising, and community participation have been applied in several European countries. These policies cover agriculture and fishery sectors, industrial and internal markets, taxation, economic and monetary policy, free movement of capital, environment, consumers, and health protection. Most communities in European Union (EU) countries must be responsible for surplus food, meal planning, and food storage to utilize wasted food to create new dishes [13,14]. In addition, initiatives to raise citizens’ awareness and reduce FW by training, campaigns such as the collaboration of stakeholders in developing new prevention methods, information supply such as informative leaflets and brochures, and improving logistics have been disseminated in EU countries. Furthermore, most of the FW programs in the EU were implemented by local municipalities or NGOs and are based on voluntary participation [15].

Several developed nations in Asia have implemented policies toward FW management and achieved good outcomes. South Korea currently boasts a recycling rate of 95 % of total FW, a big jump from recycled 2% in 1995 [16]. South Korea has made good advances in FW prevention, reduction, and recycling efforts. This result is supported by focused policies such as banning the dumping of FW and the compulsory use of biodegradable bags. In 2005, South Korea banned the direct disposal of food into landfills and approved recycled FW for use as fertilizer or animal feed [[17], [18], [19]]. Biodegradable waste bags for home use became mandatory for all South Korean citizens in 2013, and families incur the fees for each bag deposited. Bags are weighed when placed into smart bins and the depositor is charged through unique electronic ID tags. Approximately 60 % of daily municipal FW is treated for animal feed, 30 % for compost, and 10 % for anaerobic digestion. All treatment facilities in South Korea must recover and recycle at least 70 % of incoming dried FW [20]. To obtain the recycling rate, a source-separated collection system of home FW has been deployed nationwide in South Korea. In addition, a volume-based garbage disposal fee was introduced in 1995 [21] and a separate management system for FW established in 2005 [22], contributing to a reduction of general waste and FW in particular. Although the recycling processes can require large amounts of money and energy, South Korea’s waste reduction policies have been a success [21] and reductions in FW have come through the implementation of radio-frequency identification-based weighing machines, the Master Plan of Food Waste Reduction and Recycling (1998–2002) [22], awareness raising campaigns, and the waste charge system [21].

The Recycling Law of Japan was launched in 2001 to regulate and promote FW recycling from food-related industries and businesses. This law requires that industries and businesses which generate more than 100 tons of FW annually must annually submit data on the amount of FW produced and recycling rate [23,24]. The revised Food Recycling Law (2007) requires food industries to purchase farm products that are grown using FW-derived compost/animal feed [25]. In addition, the government of Japan has prepared national reports on FW generation along with food manufacturing companies, wholesalers, retailers, restaurants, and households [23] and proposed a certification system for businesses, called “recycling loops” [25].

In China, although no legislation deals with the implementation of FW directly, some FW-related policies have been implemented [17]. These are Food Security Law (2009), which regulates food waste treatment, the Grain Law, that promotes grain saving and combat food waste [26], and the Solid Waste Law (2016), which encourages the recycling and reuse of waste, including food. In general, FW policies have been ineffective in solving FW problems in China [17].

In Malaysia and Singapore, awareness programs, meal planning, penalties for illegal dumping of waste, and compulsory separation of solid waste at the source have been applied [4,14].

Policy on accepting recycled FW for animal feed varies by country. In the EU, the use of FW in animal feed is banned, whereas it is encouraged in several Asian countries such as Hong Kong, Japan, and South Korea [17,27]. In addition, Japan requires food industries to purchase farm products that are grown using FW-derived animal feed [4].

Some outstanding policies addressing FW issues that have been successfully implemented in Asian countries are penalties for illegal dumping, supported technology, meal planning, and awareness-raising, whereas in EU countries, strict regulations, initiatives, and community consensus are highlighted. Vietnam still lacks specific national policies to address the FW issue, and local initiatives to recycle or reuse FW are limited and often short-lived. These lessons and experiences from the EU or other Asian nations in dealing with FW may be useful for Vietnam.

2.2. Food waste status

As with MSW, Vietnam’s FW is not segregated into different types by the household or collection services. A small percentage of households use small buckets to contain FW, which is then collected by pig farmers; therefore, the data for FW collection and disposal at the household scale will support the development of suitable policies.

The generation rate of FW in Vietnam compared to other countries is presented in Table 1. Our 2019 study revealed that household FW in urban areas in Vietnam was 0.29 kg⸳p−1⸳d−1, accounting for 31.7 % of total waste. This is significantly higher than the rates in Lebanon with 0.20 kg⸳p−1⸳d-1 [28], Croatia with 0.21 kg⸳p⸳d−1 [29], Denmark with 0.23 kg⸳p−1⸳d−1 [30], and Norway with 0.25 kg⸳p−1⸳d-1 [31]. Notably, the Czech Republic produced a mean of 0.07 kg⸳p−1⸳d−1. However, other nations do generate a higher amount of FW, for example, the USA with 0.42 kg⸳p−1⸳d−1, Taiwan with 0.43 kg⸳p−1⸳d−1, and Luxembourg with 0.31 kg⸳p−1⸳d−1.

Table 1.

Waste generation rate in Vietnam compared with other countries.

| Region | FW generation rate (kg⸳p−1⸳d−1) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Vietnam | 0.29 | This study |

| Taiwan | 0.43 | Hanssen et al. [32] |

| USA | 0.42 | Chang et al. [33] |

| Thailand | 0.38–0.61 | Conrad et al. [34] |

| Luxembourg | 0.31 | Liu et al. [27] |

| Norway | 0.25 | Secondi et al. [16] |

| Denmark | 0.23 | Edjabou et al. [31] |

| Lebanon | 0.20 | Edjabou et al. [31] |

| Croatia | 0.21 | Chalak et al. [29] |

| Czech Republic | 0.07 | Ilakovac et al. [30] |

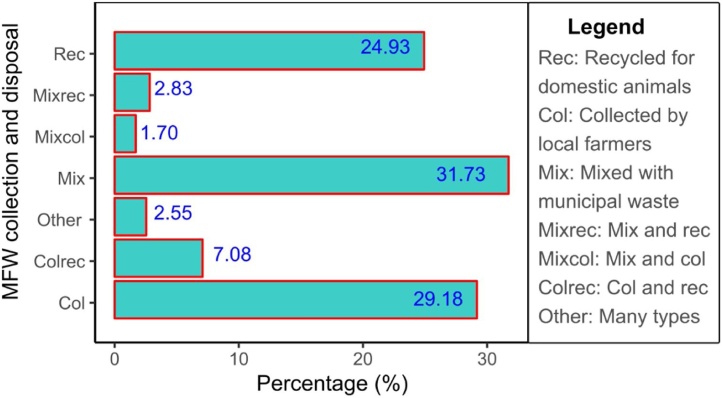

Fig. 1 shows the split of collection and disposal for FW in Vietnam. 29.18 % of FW is collected by local farmers for swine operations and 24.93 % is recycled directly for domestic animals such as chickens, ducks, and dogs. The rate of household FW disposal, from the combination of various forms, accounted for 14.16 %. FW disposed along with MSW accounts for 31.73 %. We considered 38.81 %, which includes FW discharged with MSW and disposal without collect-recycle forms, as a representative figure of overall FW which goes to landfills. This rate differs among countries. The USA estimated that 30.6 million tons of FW was landfilled, which corresponds to 22 % of all MSW going to landfills [16]. In developing countries, proportion of FW mixed into MSW that is landfilled is in the range is 20 %–80 % [35].

Fig. 1.

Percentage of food waste disposal forms from municipal households in Vietnam.

The volume of FW mixed with general solid waste generated in Vietnam is 4,429.21 ton⸳d−1. According to Thi et al. [4], the total capital cost for solid waste treatment in developing Asian countries, including costs associated with the construction, equipment, and land preparation, averaged 21.5 $⸳ton−1. The costs of waste collection transportation and treatment estimated for Vietnam’s municipalities were 20.02 $⸳ton−1 and 20.43 $⸳ton−1, respectively [36]. Therefore, Vietnam’s municipalities need to spend approximately 80,416.95 $⸳d−1 and 74,605.57 $⸳d−1 for transportation and treatment, respectively. These data imply that FW will be crucial in creating a significant change in solid waste management as well as for achieving the national goals for reusing and recycling. It is estimated that the segregation of waste sources and good FW management practices (Fig. 2) will reduce total waste by at least a third, and correspondingly, reduce the costs of collection, transportation, and management, thus easing the pressure on the environment.

Fig. 2.

FW status in Vietnam showing a) household FW put in plastic bags or small bins, b) food scraps (called “swill” by local people) collected by swine farmers, c) plastic bags containing both FW and other domestic waste, and d) unsanitary landfills and the waste-related conflicts.

The majority of FW in Vietnam is typically unavoidable at the household level and includes inedible matter such as peels, shells, bones. However food scraps (plate scraps or leftovers that went bad), and edible food components, which are usually disposed of due to local cultural characteristics, customs, or habits are also present in FW. According to a survey, the volume of this FW, a mix of leachate, semi-solids, and solids generated in Vietnam’s families is quite stable. Historically, in Vietnam, FW has been collected by local households or farmers for feeding pigs. However, over the past decade, this custom has steadily declined due to the rise in industrialization of urban areas. As a result, the rate of FW entering the MSW stream has been increasing, adding burden on local governments and pressure on the environment.

2.3. Food waste-related issue

Large volumes of food and organic waste end up in unsanitary landfills and open dumps, leading to significant environmental problems. FW contributes to global warming more than solid waste such as plastic waste through the greater release of greenhouse gases. The carbon footprint of FW is almost three times higher than that of plastic waste [37]. Moreover, FW is the biggest source of leachate (approximately 80 % moisture) in landfills. In Vietnam, FW is currently buried in landfills along with domestic waste [2] and it is of concern that FW comprises approximately half the weight of landfills in Vietnam that are not managed properly or optimally [4]. Only approximately 20 % of Vietnam’s 900 landfills are sanitary, with the remainder being unsanitary landfills or small open dumps. It is estimated that the total MSW per day buried in the unsanitary landfills is approximately 29,742 tons. Typical unsanitary landfills in Vietnam are operated in areas such as Khanh Son (Da Nang city), Tam Xuan (Quang Nam province), Duc Pho (Quang Ngai province), and Phuong Thanh (Ha Tinh province). Furthermore, overloaded landfills around residential areas have led to landfill-related conflicts. The unpleasant odors emanating from landfills, generated from decomposing organic waste, have been the primary reasons for resident protests.

Several examples of landfill-related protests in Vietnam are presented in Table 2. The three types of landfill-related conflicts and protests in Vietnam are due to odors, delayed resettlement of leachate, and proposed landfill disapproval. Protests commonly involve the blocking and preventing of garbage trucks from entering the landfills. Furthermore, several sanitary landfills, such as in the Ha Noi and Ha Tinh provinces, have seen conflicts related to delayed resettlement with regard to land supplement and financial support. In addition, the protesting of proposed landfills has increased recently in many areas of Vietnam, with locals gathering at the office of the local government to make requests.

Table 2.

Landfill-related conflicts and characteristics in Vietnam.

| Year | Provinces | Problems | Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019–2020 | Quang Nam | Odors | Blocking the roads and preventing dump trucks |

| 2007, 2015 –2019 | Da Nang | Odors, delayed resettlement, and landfill upgrades | Blocking the road and preventing dump trucks |

| 2014– 2015 | Can Tho | Odors and leachate | Preventing dump trucks |

| 2018 | Ha Tinh | Odors | Blocking the road and preventing dump trucks |

| 2019–2020 | Ha Tinh and Ha Noi |

Delayed resettlement | Blocking the road and preventing dump trucks |

| 2008–2010 | Dong Nai | Odors and leachate | Protesting landfill management agency and giving suggestions |

| 2018 | Quang Ngai | Odors | Preventing dump trucks |

| 2018–2019 | Lang Son, Hai Duong, and Thanh Hoa |

Proposed landfill | Gathering at the office of local government |

2.4. Recycling technologies

A summary of the typical recommended groups of recycling methods is presented in Table 3. Composting, biogas (anaerobic digestion), and thermal methods are frequently used recycling technologies [3,38]. In addition, incineration of FW and organic waste for energy recovery has been implemented [[39], [40], [41]]. Depending on market acceptance and the financial strength of nations, various recycling technologies for FW are applied. Japan has applied three FW recycling methods: wet feed production by sterilization with heat, dry feed production by dehydration, and incineration [23,42]. Anaerobic digestion, anaerobic co-digestion, and composting are frequently used methods for the recycling of FW in Singapore [43], whereas dry and wet feed manufacturing and compost facilities are preferred in Korea [44].

Table 3.

Typical recycled technologies for food waste.

| Technologies | Characteristics | Products |

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic digestion | Organic substrate decomposed in the absence of oxygen microbial activity and produces solid residues, liquid, and gas | Treated CH4 is useful biogas. |

| Composting | The organics converted aerobically into humus through the fermentation process. | Humus and fertilizer |

| Wet feed | FW heated to disinfect at 65–100 ℃ for a certain time | Animal feed products |

| Dry feed | Combing heating step (wet feed, 100–120 ℃) and dry-based process to produce products with a longer shelf life | Animal feed products |

| Co-processes | Incineration of FW and MSW with energy recovery or co-digestion of FW and sludge. Incineration performed at 850–1100 ℃ and co-digestion produced carbon source and biogas | Biogas, electricity and steam, humus, or reduce GHG emissions |

Anaerobic digestion has recently been preferred owing to its low cost (for small-scale), use as a renewable energy source, and co-production as nutrient-rich fertilizers [[44], [45], [46]]. The use of this method requires technically demanding construction and high financial investment (for large-scale) and failures of anaerobic digestion plants have been reported in India, Thailand, Vietnam, and Malaysia [42,47]. Similar to anaerobic digestion, composting is an appealing recycling method because of the low cost and lower requirement of chemicals, as well as because of the output of composting fertilizer [17]. This is despite the fact that many composting plants are reported to have failed or are operating inefficiently. Both composting and anaerobic digestion have stringent waste classification conditions, meaning they often have insufficient sources of food and other organic waste, and thus, their large-scale deployment is difficult. Other difficulties with composting are high running costs per unit of treatment, low-quality compost output, and difficulties in securing reliable markets for the sale of products [36]. Most large-scale composting plants using organic waste built in China, India, and Vietnam shut down or are discretely operated [48,49]. A well-segregated FW system, effective product marketing, and a decentralized scale are necessary elements to ensure a successful composting project.

Food waste to animal feed by thermal (wet-based and dry-based) and fermentation methods are considered to be low-cost, simply constructed operations, and feasible for developing countries [17,22]. Co-digestion has high potential for bio-methanation by combining FW with cattle manure, green waste, or water sludge, but longer duration can potentially cause inhibition due to improper nutrient balance [50]. The incineration of FW and MSW with energy recovery is not preferred because of their high moisture content, noncombustible components of FW [51], and byproducts of toxic air emissions and heavy metals (i.e., ash).

There is currently no proposed or implemented recycling project for FW in Vietnam. However, informal, small scale FW recycling has been operating for a long time [6,52], and cooking FW in pots under normal conditions for converting to animal feeds, particularly for pigs, is an established practice in Vietnam. Many pig farms have used FW as one of the main feed sources, although this is rapidly decreasing.

For both safety and community health, FW should be treated to make it disease-free before it is used as animal feed. Raw FW can contain bacteria and viruses and without proper treatment, can lead to diseases in animals. Despite this, there are no regulations regarding the management of FW for animal feeds in Vietnam. This situation differs globally. The EU banned FW for animal feed since 2012. According to the Swine Health Protection Act of the USA, FW must be heat treated at 100 °C for 30 min to ensure safety for swine feeding. Feeding ruminants with FW that contains mammalian proteins is also prohibited in the USA [5]. South Korea implemented strict regulations, linked with proper treatment technologies and control measures such as registration, certification, and stringent feed standards. Furthermore, the government of South Korea applied control programs that cook FW to prevent disease [50,53]. FW cooked for 30 min at 70 °C or 80 °C for 3 min, deactivates viruses such as foot-and-mouth and this is accepted as the feed safety standard in Japan and South Korea [50]. As such, FW recycling methods, such as the production of fertilizers, heat-sterilization, or controlled fermentation, rendering the products safe for feeding, are recommended in FW recycling projects [53]. These technologies are not complicated, and it is not expensive to convert FW into a safe and good quality product; therefore, they are perfectly suited to, and feasible for, Vietnamese conditions. Another option is to convert FW into fertilizers for agricultural activities, including urban farms. This practice is also well suited to the current needs of Vietnam.

2.5. Food waste biorefinery

To solve limited resource availability, and reduce pollution, the FW biorefinery concept has been developed [50]. Biomass is expected to play a vital role in fulfilling global climate targets and achieving resource-efficient biomass use by applying a circular bioeconomy [54]. Second-generation biomass composed of secondary feedstock, for example, food waste, instead of dedicated crops is attached to the concept of a sustainable circular economy.

Biorefinery is the process of converting biomass into marketable biobased products (i.e., food, feed, materials, chemicals) and energy/fuels (defined by IEA) [55]; the term can be used for a facility, a process, a plant, or even a cluster of facilities [56]. Biorefinery is one of the key strategies of the concept of a circular bioeconomy and is also the optimal approach for sustainable use of biomass waste. With the huge amount created in terms of avoidable and unavoidable types, FW can also be considered as a potential feedstock for bioeconomy or a key area in the circular economy in general [56,57]. In addition, FW biorefineries can complement fossil-based refineries to a certain extent and can enhance the major drivers of the bioeconomy.

Various bioprocesses can be implemented to convert FW to usable products such as fermentation, solventogenesis, acidogenesis, photosynthesis, methanogenesis, bioelectrogenesis, and oleaginous. These procedures generate beneficial biobased products, including chemicals, biofuels, bioelectricity, biofertilizer, animal feed, and biomass. [58]. Due to the various types of FW and biomass, a multi-feedstock biorefinery concept could be developed, in which the same value-added product was obtained from different FW [56]. However, the production of energy and biomaterials from FW is at an early stage of development [54]. Improvements and innovations in FW biorefineries need to be promoted to reduce uncertainty, increase efficiency, and encourage investment by enhancing transparency, as well as techno-economic and profitability analysis.

Vietnam’s largely agricultural economy creates a huge amount of agricultural residue. Agricultural residuals in Vietnam have been used for purposes such as biomass combustion or gasification; however, FW can also be a reliable source of biomass for general biorefinery. Although the concept of a circular bioeconomy is still quite new to Vietnam, the principle of ‘Reduce – Reuse – Recycle’ was mentioned in the National Action Plan on Green Growth and the National Strategy on Environment Protection to 2020, along with many actions that fit with the transition towards a more circular economy [57,59]. Recently, urban bioeconomy policy implemented in several smart cities in Vietnam took action with regard to FW, such as through minimization and prevention by logistics and the creation of buildings to enable recycling and re-use of nutrients [60].

FW constitutes 31.7 % of total municipal waste in Vietnam and, if segregated from the waste stream, can provide a large amount of reliable biomass for developing a circular bioeconomy. CREM [59] concluded that the total available energy equivalents produced each day to be 19, 20 GW h 2015, 2020, but can rise to 45 GW h by 2025 if all FW in Vietnam is segregated and processed by anaerobic digestion plants. This anaerobic digestion can also produce bioelectricity and could offer between 2.4%–4.1% of Vietnam's electricity demand. In a review of the potential of FW in Asia-Pacific countries, Nguyen et al. [61] reported that FW can produce valuable products (e.g., hydrogen, ethanol, enzymes, chemicals, methane) through different fermentation methods and can be more profitable than conversion to animal feed or transportation fuel. Given that the majority of Vietnam’s FW is currently landfilled, the valorization of FW is expected to bring economic and environmental benefits, especially when compared with the costs associated with greenhouse gas emissions and global warming [62]. However, the costs associated with FW valorization depend largely on the technique used; thus, the uncertainty should be carefully addressed to achieve the sustainability of biorefineries [63].

3. Policy recommendations

The results of this FW-related policy analysis infer that the attention and interest of Vietnam in terms of national plans and financial support for addressing FW are almost non-existent. The lessons and experiences from successful countries demonstrate that more effort and strict rules are necessary to solve the FW issue. Although source prevention is the ideal strategy to eliminate FW, a more feasible strategy proposed for Vietnam is to recycle FW into animal feed. Campaigns to raise awareness and promote the reduction and reuse of FW at the local scale can be implemented as part of national recycling policy. We urge the government of Vietnam to seriously consider the need for FW recycling, to enact related policies, and to support private and public sector participation in dealing with FW issues. A summary of the recommendations and steps is as follows:

First, FW reduction and recycling must be included as one of the primary national goals under the priority of national strategy on the integrated management of solid waste. All stakeholders should be involved in the decision-making process of FW strategy and policies as the experience from EU countries shows that community consensus through stakeholder participation in preparing policy is a vital factor that ensures that the initiatives and solutions are successful. Strict regulations, along with a national FW strategy, are essential.

Second, promote source segregation and deploy FW recycling projects, particularly for animal feed, fertilizers, and home composting. A combination of policy, technological support, and appropriate methods is necessary to create successful recycling projects. FW recycling methods, such as the production of fertilizers, heat-sterilization, or controlled fermentation, rendering the products safe for feeding, are recommended in FW recycling projects in Vietnam. These technologies are simple and inexpensive and are practical and feasible under Vietnamese conditions. Another option is to convert FW into fertilizers for soil amendment, which is well suited to the current needs of Vietnam. Furthermore, the support of the government for local swine farms in recycling FW to swine feed, especially for safety and community health, is critically important. This approach can immediately reduce the amount of FW collected with MSW as well as FW dumped into landfills.

Third, biorefinery needs to be considered as a sustainable and long-term solution to FW. A strategy and policy to encourage the use of FW as a reliable biomass input to the circular bioeconomy will in turn promote research and application of biotechnology to address the FW issue. Although the relationship between economic and environmental benefits and cost needs to be further investigated by large-scale projects, the potential of FW segregated for the biotechnology of anaerobic digestion is promising. This technology can produce a significant amount of bioenergy, covering between 2.4 and 4.1 % of Vietnam’s electricity demand. In addition, the residue of biogas processes can be used as fertilizer for soil amendment.

Finally, the awareness of residents and city administrations regarding their responsibilities related to FW recycling needs to be raised. Strict national regulations, along with local initiatives, will contribute to reducing FW and increasing the efficiency of waste classification. In addition, the participation of stakeholders, especially local residents (i.e., waste generators), nonprofit organizations, formal and informal sectors, government institutions, and financing institutions is essential for the local government policy-making process.

4. Conclusions

Large volumes of FW have ended up in unsanitary landfills, contributing to significant environmental problems such as global warming, high carbon footprint, leachate, and landfill-related conflicts. FW in urban areas in Vietnam is 0.29 kg⸳p−1⸳d−1, and accounts for 31.7 % of total waste, with 38.81 % of families discharging FW which, along with MSW, which corresponds to 4,429.21 ton⸳d−1 for the entire country. Approximately 80,416.95 $⸳d−1 and 74,605.57 $⸳d−1 were spent for FW collection under transportation and treatment heads, respectively. The policy attention and concern of Vietnam is not adequate for addressing the FW problem. Suggestions include setting national goals under the priority of national strategy, strict regulations, FW recycling to animal feeding, biorefinery, and raising awareness.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

X. Cuong Nguyen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft. Thi Phuong Quynh Tran: Formal analysis, Validation. T. Thanh Huyen Nguyen: Formal analysis, Validation. D. Duc La: Formal analysis, Validation. V. Khanh Nguyen: Methodology, Writing - original draft. T. Phuong Nguyen: Methodology, Writing - original draft. X.H. Nguyen: Validation, Writing - review & editing. S.W. Chang: Resources, Validation, Writing - review & editing. R. Balasubramani: Writing - review & editing. W. Jin Chung: Writing - review & editing. D. Duc Nguyen: Supervision, Project administration, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) under grant number 105.99-2019.25. The research collaboration among the groups, institutions, and universities of the authors are also grateful.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.btre.2020.e00529.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Van Den Berg K., Duong T.C. World Bank Group; Washington, D.C: 2018. Solid and Industrial Hazardous Waste Management Assessment: Options and Actions Areas. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scotland Z.W. Vol. 2020. Zero Waste Scotland; 2020. (Food Waste Worse than Plastic for Climate Change Says Zero Waste Scotland). [Google Scholar]

- 3.IFPRI . The International Food Policy Research Institute; Washington, DC: 2019. Determining Key Research Areas for Healthier Diets and Sustainable Food Systems in Viet Nam. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thi N.B.D., Kumar G., Lin C.-Y. An overview of food waste management in developing countries: current status and future perspective. J. Environ. Manage. 2015;157:220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thi D.N.B. Assessment of food waste management in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: current status and perspective. Int. J. Environ. Waste Manag. 2017;22 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cesaro J.-D., Cantard T., Leroy M.-L.N., Peyre M.-I., Huyen L.T.T., Duteurtre G. Food waste recycling with livestock farms in Hanoi: an informal service in transition. Flux. 2019;116–117(2):74–94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matete N., Trois C. Towards zero waste in emerging countries – a South African experience. Waste Manag. 2008;28(8):1480–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joseph K. Stakeholder participation for sustainable waste management. Habitat Int. 2006;30(4):863–871. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerrero L.A., Maas G., Hogland W. Solid waste management challenges for cities in developing countries. Waste Manag. 2013;33(1):220–232. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yau Y. Stakeholder engagement in waste recycling in a high‐rise setting. Sustain. Dev. 2012;20:115–127. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemke A.A., Harris-Wai J.N. Stakeholder engagement in policy development: challenges and opportunities for human genomics. Genet. Med. 2015;17(12):949–957. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corrado S., Sala S. Food waste accounting along global and European food supply chains: state of the art and outlook. Waste Manag. 2018;79:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2018.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fussions . 2015. Review of EU Legislation and Policies with Implications on Food Waste. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng B.J.H., Mao Y., Chen C.-L., Rajagopal R., Wang J.-Y. Municipal food waste management in Singapore: practices, challenges and recommendations. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2017;19(1):560–569. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia B., Ng B., Mao y., Chen C.-L., Rajagopal R., Wang J.-Y. Municipal food waste management in Singapore: practices, challenges and recommendations. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Secondi L., Principato L., Laureti T. Household food waste behaviour in EU-27 countries: a multilevel analysis. Food Policy. 2015;56:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joshi P., Visvanathan C. Sustainable management practices of food waste in Asia: technological and policy drivers. J. Environ. Manage. 2019;247:538–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen D.D., Chang S.W., Jeong S.Y., Jeung J., Kim S., Guo W., Ngo H.H. Dry thermophilic semi-continuous anaerobic digestion of food waste: performance evaluation, modified Gompertz model analysis, and energy balance. Energy Convers. Manage. 2016;128:203–210. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen D.D., Yeop J.S., Choi J., Kim S., Chang S.W., Jeon B.-H., Guo W., Ngo H.H. A new approach for concurrently improving performance of South Korean food waste valorization and renewable energy recovery via dry anaerobic digestion under mesophilic and thermophilic conditions. Waste Manag. 2017;66:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2017.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen D.D., Chang S.W., Cha J.H., Jeong S.Y., Yoon Y.S., Lee S.J., Tran M.C., Ngo H.H. Dry semi-continuous anaerobic digestion of food waste in the mesophilic and thermophilic modes: new aspects of sustainable management and energy recovery in South Korea. Energy Convers. Manage. 2017;135:445–452. [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNDP . UNDP Seoul Policy Centre; 2019. Sustainable Development. Goals Policy Brief Series No.6. Food Waste Management in Korea: Focusing on Seoul. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ju M., Bae S.-J., Kim J.Y., Lee D.-H. Solid recovery rate of food waste recycling in South Korea. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2016;18(3):419–426. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takata M., Fukushima K., Kino-Kimata N., Nagao N., Niwa C., Toda T. The effects of recycling loops in food waste management in Japan: based on the environmental and economic evaluation of food recycling. Sci. Total Environ. 2012;432:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.UNDP . UNDP Seoul Policy Centre; 2019. Sustainable Development Goals. Policy Brief Series No.3. Comprehensive Study of Waste Management Policies & Practices in Korea and Recommendations for LDCs and MICs. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu C., Hotta Y., Santo A., Hengesbaugh M., Watabe A., Totoki Y., Allen D., Bengtsson M. Food waste in Japan: trends, current practices and key challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2016;133 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xinjun 胡., Min 张., Junfeng 余., Guren 张. Food waste management in China: status, problems and solutions. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2012;32:4575–4584. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu C., Mao C., Bunditsakulchai P., Sasaki S., Hotta Y. Food waste in Bangkok: current situation, trends and key challenges. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020;157 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takata M., Fukushima K., Kino-Kimata N., Nagao N., Niwa C., Toda T. The effects of recycling loops in food waste management in Japan: based on the environmental and economic evaluation of food recycling. Sci. Total Environ. 2012;432:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chalak A., Abiad M.G., Diab M., Nasreddine L. The determinants of household food waste generation and its associated caloric and nutrient losses: the case of Lebanon. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0225789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ilakovac B., Voca N., Pezo L., Cerjak M. Quantification and determination of household food waste and its relation to sociodemographic characteristics in Croatia. Waste Manag. 2020;102:231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edjabou M.E., Petersen C., Scheutz C., Astrup T.F. Food waste from Danish households: generation and composition. Waste Manag. 2016;52:256–268. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2016.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanssen O.J., Syversen F., Stø E. Edible food waste from Norwegian households—detailed food waste composition analysis among households in two different regions in Norway. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016;109:146–154. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang Y.-C., Chu-Yen W., Chilumbu C., Wan-Ying H., Hou-Wang S. 2019. Does Culture Matter? Motivations and Barriers to Minimizing Household Food Waste. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conrad Z., Niles M.T., Neher D.A., Roy E.D., Tichenor N.E., Jahns L. Relationship between food waste, diet quality, and environmental sustainability. PLoS One. 2018;13(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.USEPA . U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Report an environmental violation; 2017. Food: Material-Specific Data. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aleluia J., Ferrão P. Assessing the costs of municipal solid waste treatment technologies in developing Asian countries. Waste Manag. 2017;69:592–608. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2017.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Committee H.C.Ps. In: Decree on Maximum Prices for Waste Collection, Transportation and Treatment Services Using the State Budget Capital Source. Committee H.C.Ps., editor. HCM City; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banu R., Kumar G., Gunasekaran M., Kavitha S. Academic Press; 2020. Food Waste to Valuable Resources: Applications and Management. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lam C.-M., Yu I.K.M., Hsu S.-C., Tsang D.C.W. Chapter 18 – life-cycle assessment of food waste recycling. In: Bhaskar T., Pandey A., Rene E.R., Tsang D.C.W., editors. Waste Biorefinery. Elsevier; 2020. pp. 481–513. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajesh Banu J., Merrylin J., Mohamed Usman T.M., Yukesh Kannah R., Gunasekaran M., Kim S.-H., Kumar G. Impact of pretreatment on food waste for biohydrogen production: a review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakai S.-i., Yoshida H., Hirai Y., Asari M., Takigami H., Takahashi S., Tomoda K., Peeler M.V., Wejchert J., Schmid-Unterseh T., Douvan A.R., Hathaway R., Hylander L.D., Fischer C., Oh G.J., Jinhui L., Chi N.K. International comparative study of 3R and waste management policy developments. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2011;13(2):86–102. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meena R.A.A., Rajesh Banu J., Yukesh Kannah R., Yogalakshmi K.N., Kumar G. Biohythane production from food processing wastes – challenges and perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2020;298 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogata Y., Ishigaki T., Nakagawa M., Yamada M. Effect of increasing salinity on biogas production in waste landfills with leachate recirculation: a lab-scale model study. Biotechnol. Rep. 2016;10:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khoo H.H., Lim T.Z., Tan R.B.H. Food waste conversion options in Singapore: environmental impacts based on an LCA perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2010;408(6):1367–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeong S.Y., Chang S.W., Ngo H.H., Guo W., Nghiem L.D., Banu J.R., Jeon B.-H., Nguyen D.D. Influence of thermal hydrolysis pretreatment on physicochemical properties and anaerobic biodegradability of waste activated sludge with different solids content. Waste Manag. 2019;85:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2018.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu F., Li Y., Ge X., Yang L., Li Y. Anaerobic digestion of food waste – challenges and opportunities. Bioresour. Technol. 2018;247:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saha B., Devi C., Khwairakpam M., Kalamdhad A.S. Vermicomposting and anaerobic digestion – viable alternative options for terrestrial weed management – a review. Biotechnol. Rep. 2018;17:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cerda A., Artola A., Font Segura X., Barrena R., Gea T., Sánchez A. Composting of food wastes: status and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2017;248 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.06.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dou X. Food waste generation and its recycling recovery: China’s governance mode and its assessment. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2015;24:1474–1482. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dou Z., Toth J.D., Westendorf M.L. Food waste for livestock feeding: feasibility, safety, and sustainability implications. Glob. Food Sec. 2018;17:154–161. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paritosh K., Kushwaha S.K., Yadav M., Pareek N., Chawade A., Vivekanand V. Food waste to energy: an overview of sustainable approaches for food waste management and nutrient recycling. Biomed Res. Int. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/2370927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pham T.P.T., Kaushik R., Parshetti G.K., Mahmood R., Balasubramanian R. Food waste-to-energy conversion technologies: current status and future directions. Waste Manag. 2015;38:399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferguson J.D. Food residue, loss and waste as animal feed. In: Hashmi S., Choudhury I.A., editors. Encyclopedia of Renewable and Sustainable Materials. Elsevier; Oxford: 2020. pp. 395–407. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caldeira C., Vlysidis A., Fiore G., De Laurentiis V., Vignali G., Sala S. Sustainability of food waste biorefinery: a review on valorisation pathways, techno-economic constraints, and environmental assessment. Bioresour. Technol. 2020;312 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stegmann P., Londo M., Junginger M. The circular bioeconomy: its elements and role in European bioeconomy clusters. Resour. Conserv. Recycl.: X. 2020;6 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dahiya S., Amradi N., Sravan J.S., Chatterjee S., Sarkar O., Venkata Mohan S. Food waste biorefinery: sustainable strategy for circular bioeconomy. Bioresour. Technol. 2017;248 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.07.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Imbert E. Food waste valorization options: opportunities from the bioeconomy. Open Agric. 2017;2 [Google Scholar]

- 58.EC . European Commission; 2017. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, on the Implementation of the Circular Economy Action Plan. [Google Scholar]

- 59.CREM . 2018. Scoping Study Circular Economy in Vietnam. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hai H., Nguyen D.-Q., Thang N., Hoang Nguyen N. 2020. Circular Economy in Vietnam; pp. 423–452. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nguyen H., Heaven S., Banks C. Energy potential from the anaerobic digestion of food waste in municipal solid waste stream of urban areas in Vietnam. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 2014;5:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uçkun Kiran E., Trzcinski A.P., Ng W.J., Liu Y. Enzyme production from food wastes using a biorefinery concept. Waste Biomass Valorization. 2014;5(6):903–917. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xiong X., Yu I.K.M., Tsang D.C.W., Bolan N.S., Sik Ok Y., Igalavithana A.D., Kirkham M.B., Kim K.-H., Vikrant K. Value-added chemicals from food supply chain wastes: state-of-the-art review and future prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;375 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.