Abstract

Background

Antidepressant drugs have shown antitumor activity in preclinical glioblastoma studies. Antidepressant drug use, as well as its association with survival, in glioblastoma patients has not been well characterized on a population level.

Methods

Patient characteristics, including the frequency of antidepressant drug use, were assessed in a glioblastoma cohort diagnosed in a 10-year time frame between 2005 and 2014 in the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland. Cox proportional hazards regression models were applied for multivariate analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to estimate overall survival (OS) data and the log-rank test was performed for comparisons.

Results

A total of 404 patients with isocitrate dehydrogenase wild-type glioblastoma were included in this study. Sixty-five patients (16.1%) took antidepressant drugs at some point during the disease course. Patients were most commonly prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors at any time (N = 46, 70.8%). Nineteen patients (29.2%) were on antidepressant drugs at the time of their tumor diagnosis. No differences were observed in OS between those patients who had taken antidepressants at some point in their disease course and those who had not (P = .356). These data were confirmed in a multivariate analysis including age, Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS), sex, extent of resection, O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation status, and first-line treatment as cofounders (P = .315). Also, there was no association of use of drugs modulating voltage-dependent potassium channels (citalopram; escitalopram) with survival (P = .639).

Conclusions

This signal-seeking study does not support the hypothesis that antidepressants have antitumor efficacy in glioblastoma on a population level.

Keywords: antidepressants, depression, epidemiology, glioblastoma, survival

Glioblastoma is the most common malignant primary brain tumor in adults.1 Despite multimodal care regimens, including maximum safe tumor resection, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy,2,3 prognosis remains poor with a median survival of 11 to 14 months4,5 and a 5-year survival rate of 5.6% on a population-based level.1 Glioblastoma causes cognitive deficits and psychiatric comorbidity, such as depression, anxiety, or fatigue.6–8 The prevalence of depression among brain tumor patients has been reported in a wide range of less than 1%9 to up to 90%10 of patients and is likely highly dependent on the methodology used to assess depressive symptoms. Patient-rated analyses showed higher prevalence of depression (27%) than clinician-rated measures (15%), as discussed in a systematic review of observational studies on depression in glioma.11 This study found a prevalence of depression in about 15% of glioma patients. The presence of depressive symptoms may be independently associated with shorter overall survival (OS) in glioblastoma patients.12 In preclinical models, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) such as imipramine or amitriptyline acting as mixed norepinephrine and serotonin uptake inhibitors can impair the malignant phenotype of glioma cells by inhibiting cellular respiration, an indicator of apoptosis.13,14 Moreover, imipramine and amitriptyline inhibit the expression of p65 nuclear factor-κB, frequently overexpressed in glioblastoma cells, which results in reduced tumor cell proliferation, motility, and survival.15,16 In vitro data suggest a role for voltage-dependent potassium channels as therapeutic targets in gliomas, which can be modulated by different classes of antidepressants.17,18 The Kv10.1 subtype of potassium channels is highly expressed in gliomas.19 Imipramine, a TCA, binds to these Kv10.1 channels and decreases the proliferation rate of cancer cells.20 Glioma cells exhibit a high mitochondrial membrane potential and low expression of Kv1.5 channels. Citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), acts on the Kv1.5 subtype as an open-channel blocker and increases the intracellular potassium concentration, leading to decreased resistance to apoptosis.21,22 Escitalopram, a stereoisomer of citalopram, also inhibits voltage-dependent potassium channels, but data regarding its activity against glioma cells are lacking.23 Imipramine also inhibits the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and induces autophagic cell death in U-87MG glioma cells.24 Finally, there is evidence from a mouse model suggesting that fluoxetine, an SSRI, can suppress the growth of experimental gliomas by directly binding to the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR).25

On a population-based level, the prevalence of antidepressant drug use among glioblastoma patients as a surrogate marker for depression or depressive symptoms, as well as the association of use of such agents with survival, remains unclear.

Methods

Patient Identification

All patients age 18 years or older who were inhabitants of the Canton of Zürich, Switzerland, and diagnosed with glioblastoma between 2005 and 2014 were included in a glioblastoma cancer registry in the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland. Patient identification data were provided by the Cancer Registry of the Cantons Zurich and Zug. Epidemiological data on this patient cohort have been published previously.4,5 For the present analysis, we excluded all patients who lacked molecular data on isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)-mutation status based on the present World Health Organization (WHO) classification,26 or who had insufficient patient documentation on antidepressant drug use (see Supplementary Figure 1).

Disease Characteristics

All tumors in the glioblastoma cancer registry had been classified according to the WHO 2007 criteria27 in the local pathology departments, and in a second step were classified by IDH-mutation status in accordance with the WHO 2016 classification.26 O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation status was determined by methylation-specific PCR. IDH-mutation status was obtained by immunohistochemistry for IDH1 R132H, mainly based on the suggestion that sequencing may not be needed in patients older than 55 years.26 Extent of resection was determined by early postoperative MRI or, if no MRI was available, by cranial CT. Macroscopic (gross) total resection was defined by the absence of contrast enhancement.28 Data on use of antidepressant drugs were extracted from clinical records. For most patients we had access to all appropriate medical records provided by the caregivers of the patients who we contacted directly. For patients seen at the University Hospital in Zurich the drug use in general was documented almost every time the patient had an appointment. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude that there are patients who received antidepressants that we were not aware of.

Statistical Analyses

Demographical, clinical, molecular marker, and use of antidepressant drug data were obtained to apply descriptive statistics. The chi-square test was performed for analysis of nominal variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for the comparison of quantitative variables between the 2 patient cohorts of antidepressant drug users and nonusers. OS was calculated from primary surgery to death or last follow-up. Patients were censored at last follow-up. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate OS in the antidepressant drug users and nonusers, and differences were analyzed using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used for multivariate analysis to test the association of clinical and molecular factors, as well as use of antidepressant drugs with outcome. The multivariate model was applied to all patients who had complete information on all tested covariables. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, version 24 (IBM Corporation) statistical software, and a P value of .05 was set as statistically significant.

Ethics

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Canton of Zurich (KEK-ZH-Nr. 2009-0135/1; KEK-ZH-Nr. 2015-0437).

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 404 patients with IDH wild-type glioblastoma were included in this retrospective study; 65 of these 404 patients (16.1%) took antidepressant drugs at some point during their disease course. Patient characteristics of the 2 subpopulations, the nonantidepressant cohort (N = 339) and antidepressant cohort (N = 65), are summarized in Table 1. Age, sex, Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS), extent of resection, and first-line treatment after initial surgery were balanced between both patient cohorts. Patients who received antidepressants more frequently had a methylated MGMT promoter methylation status than patients who did not (P = .014). The distribution of the KPS differed between both patient groups (P = .033). Comparing the use of antidepressant drugs over the analyzed 10-year time frame, the frequency of use of antidepressant drugs among glioblastoma patients decreased over the years from 23.7% (N = 40 patients out of N = 169 patients) in the years 2005 through 2009 to 10.6% (N = 25 patients out of N = 235 patients) in the years 2010 through 2014 (P = .001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics, Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Wild-Type Cohort

| Nonantidepressant drug cohort N = 339 | Antidepressant drug cohort N = 65 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| Median | 62.8 | 61.3 | .878 |

| Range | 18-90 | 31-86 | |

| Sex, N, % | |||

| Male | 216 (63.7) | 40 (61.5) | .738 |

| Female | 123 (36.2) | 25 (38.5) | |

| KPSa, N, % | |||

| 90-100 | 54 (16.1) | 5 (7.7) | .033 |

| 70-80 | 191 (56.8) | 48 (73.8) | |

| < 70 | 91 (27.1) | 12 (18.5) | |

| No data | 3 | – | |

| Extent of surgical resectiona, N, % | |||

| Gross total resection | 56 (16.6) | 6 (9.2) | .395 |

| Incomplete resection | 202 (59.8) | 45 (69.2) | |

| Biopsy | 79 (23.4) | 14 (21.5) | |

| Autopsy | 1 (0.3) | – | |

| No data | 1 | – | |

| First-line therapy, N, % | |||

| RT plus TMZ | 170 (50.1) | 33 (50.8) | .538 |

| RT alone | 65 (19.2) | 11 (16.9) | |

| Chemotherapy alone | 25 (7.4) | 2 (3.1) | |

| Othersb | 23 (6.8) | 4 (6.2) | |

| No therapy | 51 (15.0) | 14 (21.5) | |

| No data | 5 | 1 | |

| MGMT promoter methylation status, N, % per number of patients with assessed data | |||

| Methylated | 97 (40.9) | 30 (60.0) | .014 |

| Unmethylated | 140 (59.1) | 20 (40.0) | |

| No data | 102 | 15 | |

| Analyzed time frame | |||

| 2005-2009 | 129 (38.1) | 40 (61.5) | < .001 |

| 2010-2014 | 210 (61.9) | 25 (38.4) |

Abbreviations: KPS, Karnofsky Performance Scale; N, number of patients; MGMT, O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase; RT, radiotherapy; TMZ, temozolomide.

Chemotherapy consisted mostly of alkylating chemotherapy.

aAt time of diagnosis.

bMainly experimental drugs in clinical trials, or bevacizumab.

Patterns of Antidepressant Drug Use

Patients who had taken antidepressant drugs at the time of their glioblastoma diagnosis most often received SSRI (68.4%), followed by tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs) (36.8%), and selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRIs) (5.3%). After 3 and 6 months since beginning to take antidepressants, about half the patients continued treatment (57.9% and 47.4%, respectively). When focusing on antidepressants at any time during the course of the disease, SSRIs were still the most frequently used drugs (70.8%), especially citalopram (33.8%); 15.4% of all patients received more than one antidepressant agent (Table 2). Additionally, of the 65 antidepressant drug-taking patients, 41 (63.1%) were on comedication with benzodiazepines at some point during their disease trajectory (see Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2.

Antidepressant Drug Use in Glioblastoma Patients, Stratified by Mode of Action and Time Point

| Antidepressant drug cohort | |

|---|---|

| Antidepressants at time of diagnosis, N | 19 |

| Type of antidepressant drug, N, % of those with antidepressant drug use at diagnosisa | |

| TeCA (mirtazapine) | 7 (36.8) |

| SSRI | 13 (68.4) |

| Citalopram | 6 (31.6) |

| Escitalopram | 5 (26.3) |

| Fluoxetine | 1 (5.3) |

| Sertraline | 1 (5.3) |

| SSNRI (venlafaxine) | 1 (5.3) |

| Antidepressants 3 mo after diagnosis, N, % of those with antidepressant drug use at diagnosis | |

| Ongoing | 11 (57.9) |

| Not ongoing | 2 (10.5) |

| Switched antidepressants | 3 (15.8) |

| No data | 3 (15.8) |

| Antidepressants 6 mo after diagnosis, N, % of those with antidepressant drug use at diagnosis | |

| Ongoing | 9 (47.4) |

| Not ongoing | 1 (5.3) |

| Switched antidepressants | 3 (15.8) |

| No data | 6 (31.6) |

| Antidepressants at any time, N | 65 |

| Type of antidepressant drug, N, % of those with any antidepressant drug usea | |

| TCA (amitriptyline) | 1 (1.5) |

| TeCA (mirtazapine) | 23 (35.4) |

| SSRI | 46 (70.8) |

| Citalopram | 22 (33.8) |

| Escitalopram | 16 (24.6) |

| Fluoxetine | 1 (1.5) |

| Sertraline | 7 (10.8) |

| SSNRI (venlafaxine) | 5 (7.7) |

| Multiple antidepressantsb | 10 (15.4) |

| SSRI and TeCA | 7 (10.8) |

| SSRI and SSNRI | 1 (1.5) |

| Multiple SSRIs | 1 (1.5) |

| TeCA and SSNRI | 1 (1.5) |

Abbreviations: N, number of patients; SSNRI, selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; TeCA, tetracyclic antidepressant.

aPatients could have taken more than one antidepressant drug at the same time.

bEach antidepressant in this category has been counted in its individual group as well.

Outcome Data

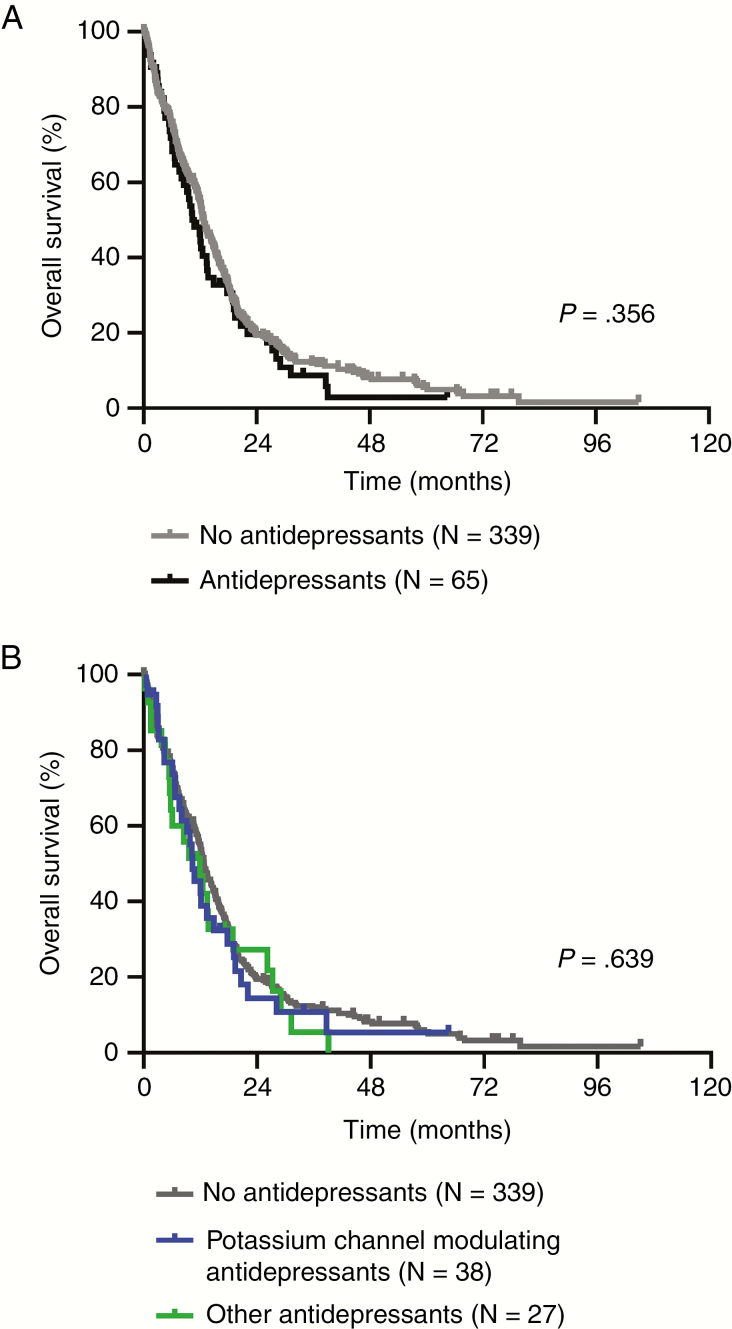

Median OS was 12.8 months (95% CI, 11.4-14.1 months) for patients without antidepressant drug use and 10.8 months (95% CI, 7.9-13.6 months) for patients who had taken antidepressants at any time during the course of the disease (Table 3). None of the patients included in this study were reported to have committed suicide. OS data, estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves, for the antidepressant drug-taking and nonusing subgroups are displayed in Figure 1A. Although there was a trend toward worse survival in patients with antidepressant drug use when compared to nonusers, no statistically significant differences were observed (P = .356) (see Table 3 and Figure 1A).

Table 3.

Overall Survival Data, Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Wild-Type Cohort

| N (events) | Median OS, mo (95% CI) | OS 12 mo, % (SE; remaining cases) | OS 24 mo, % (SE; remaining cases) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | |||||

| No antidepressants | 339 (281) | 12.8 (11.4-14.1) | 54.4 (2.8; 160) | 19.0 (2.3; 52) | .356 |

| Antidepressants | 65 (51) | 10.8 (7.9-13.6) | 44.3 (6.7; 23) | 17.5 (5.4; 8) | |

| All patients | |||||

| Methylated MGMT promoter | 127 (101) | 14.2 (9.3-19.0) | 61.5 (4.5; 68) | 31.3 (4.5; 32) | .004 |

| Unmethylated MGMT promoter | 160 (136) | 12.2 (10.8-13.6) | 51.7 (4.2; 71) | 14.0 (3.0; 18) | |

| Patients with a methylated MGMT promoter | |||||

| No antidepressants | 97 (78) | 14.4 (8.7-20.0) | 61.2 (5.1; 53) | 33.2 (5.1; 26) | .423 |

| Antidepressants | 30 (23) | 13.4 (11.4-15.3) | 62.4 (9.4; 16) | 25.0 (8.7; 6) | |

| Patients with an unmethylated MGMT promoter | |||||

| No antidepressants | 140 (121) | 12.3 (10.7-13.8) | 52.4 (4.4; 64) | 12.8 (3.1; 15) | .787 |

| Antidepressants | 20 (15) | 11.9 (6.7-17.1) | 45.2 (12.5; 7) | 23.2 (11.2; 3) |

Abbreviations: MGMT, O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase; N, number of patients; OS, overall survival.

Figure 1.

Antidepressant Drugs and Survival A, Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival are shown for patients who took antidepressant drugs (black) or who had not taken antidepressant drugs (gray) at any time during the course of the disease. B, The same Kaplan-Meier survival curves are shown stratified for patients who took drugs modulating voltage-dependent potassium channels (blue; citalopram, escitalopram) and those who had not taken any other antidepressant drugs (green). The log-rank test was used for comparison.

The 2 patient cohorts, antidepressant and nonantidepressant drug users, were not balanced regarding the MGMT promoter methylation status (Table 1). Therefore, survival curves were analyzed separately for patients with tumors with a methylated or unmethylated MGMT promoter. A trend toward inferior survival was noticed for antidepressant drug users in both patient cohorts, especially in the patients with a methylated MGMT promoter methylation status, but for both patient subgroups this did not reach statistical significance (methylated MGMT promoter status P = .423, unmethylated MGMT promoter status P = .787) (see Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 2).

When analyzing the two 5-year time frames separately, no association with OS was seen (Supplementary Table 2). In a subgroup analysis focused on those patients who had taken antidepressant drugs previously reported to modulate voltage-dependent potassium channels in glioma cells,17 such as citalopram (N = 22) or escitalopram (N = 16) (median OS 10.4 months, 95% CI, 7.4-13.4 months), no association with OS was seen compared to patients with any other antidepressant drug use (median OS 11.9 months, 95% CI, 6.0-17.9 months; P = .920) or no antidepressant medication (median OS 12.8 months, 95% CI, 11.4-14.1 months; P = .551) (Figure 1B).

Multivariate Analysis With Regards to Death

Multivariate analysis was performed to assess the association of clinical and molecular parameters with OS. The analysis confirmed known prognostic or predictive markers in glioblastoma, including age, KPS, extent of resection, MGMT promoter methylation status, or first-line treatment. Antidepressant drug use at any time during the course of the disease was not associated with survival (hazard ratio 0.83, 95% CI, 0.58-1.19) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis With Regards to Death (Cox Regression)

| N | HR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| > 65 | 120 | 1 | (Reference) |

| ≤ 65 | 162 | 0.70 (0.51-0.97) | .030 |

| KPSa, % | |||

| < 70 | 67 | 2.22 (1.58-3.11) | < .001 |

| 70-80 | 171 | 1 | (Reference) |

| 90-100 | 44 | 0.68 (0.46-1.01) | .054 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 185 | 1 | (Reference) |

| Female | 97 | 1.16 (0.88-1.54) | .302 |

| Extent of resection | |||

| Biopsy | 50 | 1 | (Reference) |

| Incomplete | 194 | 0.38 (0.26-0.56) | < .001 |

| Gross total (≥ 99%) | 38 | 0.22 (0.13-0.36) | < .001 |

| MGMT promoter methylation status | |||

| Unmethylated | 159 | 1 | (Reference) |

| Methylated | 123 | 0.31 (0.17-0.55) | < .001 |

| Postsurgical therapy | |||

| No therapy | 34 | 2.67 (1.6-4.48) | < .001 |

| RT alone | 51 | 1 | (Reference) |

| Chemotherapy alone | 23 | 0.95 (0.54-1.67) | .848 |

| RT plus TMZ | 156 | 0.44 (0.29-0.67) | < .001 |

| Othersb | 18 | 0.40 (0.21-0.77) | .006 |

| Antidepressant drug | |||

| No | 233 | 0.83 (0.58-1.19) | .315 |

| Yes | 49 | 1 | (Reference) |

Abbreviations: CT, chemotherapy; HR, hazard ratio; MGMT, O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase; RT, radiotherapy; TMZ, temozolomide.

aAt time of diagnosis.

bMainly experimental drugs in clinical trials, or bevacizumab.

Conclusions

Antidepressant drugs may be given to glioblastoma patients for different reasons, including depression, fatigue, anxiety, or inappetence. These symptoms may be caused by the tumor itself, tumor-specific treatments, side effects of medications, or a psychiatric disorder in the medical history.8,11,29 In our cohort study in the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland, 65 patients (16.1%) diagnosed with IDH wild-type glioblastoma were taking antidepressant drugs at some time during the course of disease (see Table 1). Assuming that most patients received these drugs because of psychiatric morbidities, mainly depressive symptoms and that therefore antidepressant drug use can be used as a surrogate marker for depression, the frequency of depression in this cohort is in line with data of observational studies published in 2010,11 although higher prevalence rates have also been reported.10 This may underline differences in the awareness of psychiatric disorders in glioblastoma patients, which can be influenced by social, cultural, and other regional factors. Interestingly, use of antidepressant drugs among glioblastoma patients decreased over the years in Zurich, Switzerland (see Supplementary Table 2). Not all glioblastoma patients diagnosed with psychiatric symptoms receive drugs, and nonmedication approaches to psychiatric comorbidity may be more compatible with social life. Importantly, there may be an increased awareness for such nonpharmaceutical approaches to treating psychiatric symptoms and comorbidities in the general population. This is also shown by increased use of complementary and alternative medicine in glioma patients.30,31

Putative molecular mechanisms of anticancer activity of antidepressant drugs include modulations of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway,24 AMPAR-mediated calcium-dependent apoptosis,25 influencing the mitochondrial machinery,14,21 or targeting voltage-dependent potassium channels.17,18 In our population-based study, no association was found between the use of antidepressant drugs and survival (see Figure 1A and Table 3). Moreover, although not statistically significant, median OS was numerically inferior in the antidepressant cohort compared to patients who had not taken antidepressant drugs, independent of MGMT promoter methylation status (see Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 2). The same was true when we analyzed the subgroup of patients who had taken antidepressant drugs that interfered with voltage-dependent potassium channels, including citalopram and escitalopram (both SSRIs) (see Figure 1B). In line with our data, in a retrospective study performed at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, US, no association of SSRI use with survival in glioblastoma patients was found.32 In contrast to our data in glioblastoma patients, the opposite was seen in non-CNS cancers, such as breast cancer.33,34

Limitations of our study include its retrospective nature, as well as the lack of data on the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders, and intensity of treatment with antidepressants. However, medications, including antidepressant drugs, were documented routinely in most patients. Based on the retrospective nature of data collection, the prevalence of drug prescription may be underestimated.

The administration of antidepressant drugs at the time of diagnosis or during the course of the disease was not associated with survival in our glioblastoma cohort. This study does not support the hypothesis that antidepressant drugs may have antitumor efficacy on a population-based level, not excluding the possibility of a subpopulation effect not addressed by our study design. However, further investigation, mainly in prospective studies and with a standardized psychiatric assessment, may be necessary to dissect any associations of psychiatric comorbidity and the associated therapeutic interventions with outcome.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Krebsliga Zurich and by a grant from the Betty and David Koetser Foundation for Brain Research of the University of Zurich, Switzerland (no grant number is applicable), and a personal grant (“Filling the gap”) of the University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland (FTG-1415-002 to D.G.), and a personal grant (ThinkSwiss scholarship program; Office of Science, Technology and Higher Education at the Embassy of Switzerland in the United States of America, Washington, DC, to J.L.R.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and their families for making this study possible and acknowledge the contributions of the multidisciplinary teams taking care of glioblastoma patients in the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland.

Conflict of interest statement.

M.W. has received research grants from Abbvie, Adastra, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Dracen, Merck, Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Merck (EMD), Novocure, Piqur, and Roche; and honoraria for lectures or advisory board participation or consulting from Abbvie, Basilea, BMS, Celgene, MSD, EMD, Novocure, Orbus, Roche, and Tocagen. P.R. has received research grants from MSD and Novocure and honoraria for advisory board participation or lectures from BMS, Covagen, Debiopharm, Medac, MSD, Novartis, Novocure, QED, Roche, and Virometix. E.L.R. has received research grants from Mundipharma and Amgen; and personal fees from Abbvie, Daiichi Sankyo, Mundipharma, Novartis. All remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Gittleman H, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2012-2016. Neuro Oncol. 2019; 21(suppl 5):v1–v100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weller M, Le Rhun E, Preusser M, Tonn JC. Roth P.. How we treat glioblastoma. ESMO Open. 2019;4(suppl 2):e000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weller M, van den Bent M, Tonn JC, et al. ; European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) Task Force on Gliomas European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of adult astrocytic and oligodendroglial gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(6):e315–e329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gramatzki D, Dehler S, Rushing EJ, et al. Glioblastoma in the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland revisited: 2005 to 2009. Cancer. 2016;122(14):2206–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gramatzki D, Roth P, Rushing EJ, et al. Bevacizumab may improve quality of life, but not overall survival in glioblastoma: an epidemiological study. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(6):1431–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hewins W, Zienius K, Rogers JL, Kerrigan S, Bernstein M, Grant R.. The effects of brain tumours upon medical decision-making capacity. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21(6):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Steinbach JP, Blaicher HP, Herrlinger U, et al. Surviving glioblastoma for more than 5 years: the patient’s perspective. Neurology. 2006;66(2):239–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coomans MB, Dirven L, Aaronson NK, et al. Symptom clusters in newly diagnosed glioma patients: which symptom clusters are independently associated with functioning and global health status? Neuro Oncol. 2019;21(11):1447–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anderson SI, Taylor R, Whittle IR. Mood disorders in patients after treatment for primary intracranial tumours. Br J Neurosurg. 1999;13(5):480–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Litofsky NS, Farace E, Anderson F Jr, Meyers CA, Huang W, Laws ER Jr; Glioma Outcomes Project Investigators Depression in patients with high-grade glioma: results of the Glioma Outcomes Project. Neurosurgery. 2004;54(2):358–3 66; discussion 366-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rooney AG, Carson A, Grant R. Depression in cerebral glioma patients: a systematic review of observational studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(1):61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Noll KR, Sullaway CM, Wefel JS. Depressive symptoms and executive function in relation to survival in patients with glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2019;142(1):183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Higgins SC, Pilkington GJ. The in vitro effects of tricyclic drugs and dexamethasone on cellular respiration of malignant glioma. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(2):391–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bielecka-Wajdman AM, Ludyga T, Machnik G, Gołyszny M, Obuchowicz E.. Tricyclic antidepressants modulate stressed mitochondria in glioblastoma multiforme cells. Cancer Control. 2018;25(1):1073274818798594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Soubannier V, Stifani S. NF-κB signalling in glioblastoma. Biomedicines. 2017;5(2):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shchors K, Massaras A, Hanahan D. Dual targeting of the autophagic regulatory circuitry in gliomas with repurposed drugs elicits cell-lethal autophagy and therapeutic benefit. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(4):456–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lefranc F, Pouleau HB, Rynkowski M, De Witte O.. Voltage-dependent K+ channels as oncotargets in malignant gliomas. Oncotarget. 2012;3(5):516–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lefranc F, Le Rhun E, Kiss R, Weller M.. Glioblastoma quo vadis: will migration and invasiveness reemerge as therapeutic targets? Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;68:145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martínez R, Stühmer W, Martin S, et al. Analysis of the expression of Kv10.1 potassium channel in patients with brain metastases and glioblastoma multiforme: impact on survival. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pardo LA, Gómez-Varela D, Major F, et al. Approaches targeting K(V)10.1 open a novel window for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19(5):675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bonnet S, Archer SL, Allalunis-Turner J, et al. A mitochondria-K+ channel axis is suppressed in cancer and its normalization promotes apoptosis and inhibits cancer growth. Cancer Cell. 2007;11(1):37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Checchetto V, Azzolini M, Peruzzo R, Capitanio P, Leanza L.. Mitochondrial potassium channels in cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;500(1):51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim HS, Li H, Kim HW, et al. Escitalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, inhibits voltage-dependent K(+) channels in coronary arterial smooth muscle cells. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2017;21(4):415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jeon SH, Kim SH, Kim Y, et al. The tricyclic antidepressant imipramine induces autophagic cell death in U-87MG glioma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;413(2):311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu K-H, Yang ST, Lin Y-K, et al. Fluoxetine, an antidepressant, suppresses glioblastoma by evoking AMPAR-mediated calcium-dependent apoptosis. Oncotarget. 2015;6(7):5088–5101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(6):803–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(2):97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stummer W, Reulen HJ, Meinel T, et al. ; ALA–Glioma Study Group Extent of resection and survival in glioblastoma multiforme: identification of and adjustment for bias. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(3): 564–5 76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pangilinan PH, Kelly BM, Pangilinan JM. Depression in the patient with brain cancer. Community Oncol. 2007;9(4):533–537. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Le Rhun E, Devos P, Bourg V, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in glioma patients in France. J Neurooncol. 2019;145(3):487–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eisele G, Roelcke U, Conen K, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use by glioma patients in Switzerland. Neurooncol Pract. 2019;6(3):237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Caudill JS, Brown PD, Cerhan JH, Rummans TA.. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, glioblastoma multiforme, and impact on toxicities and overall survival: the Mayo Clinic experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2011;34(4):385–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boursi B, Lurie I, Haynes K, Mamtani R, Yang YX. Chronic therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and survival in newly diagnosed cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(1):e12666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pezzella G, Moslinger-Gehmayr R, Contu A. Treatment of depression in patients with breast cancer: a comparison between paroxetine and amitriptyline. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;70(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.