Abstract

Current theories conceptualize return migration to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina as an individual-level assessment of costs and benefits. Since relocation is cost prohibitive, return migration is thought to be unlikely for vulnerable populations. However, recent analyses of longitudinal survey data suggest that these individuals are likely to return to New Orleans over time despite achieving socioeconomic gains in the post-disaster location. I extend the “context of reception” approach from the sociology of immigration and draw on longitudinal data from the Resilience in the Survivors of Katrina Project to demonstrate how institutional, labor market, and social contexts influence the decision to return. Specifically, I show how subjective comparisons of the three contexts between origin and destination, perceived experiences of discrimination within each context, and changing contexts over time explain my sample’s divergent migration and mobility outcomes. I conclude with implications for future research on, and policy responses to, natural disasters.

Keywords: Contexts of reception, Post-disaster migration, Socioeconomic mobility, Natural disasters, Hurricane Katrina, Vulnerable populations, Mixed methodology

Introduction

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina decimated the Gulf Coast, prompting the evacuation of 1.1 million people and the protracted displacement of 650,000 civilians to cities such as Baton Rouge, Dallas, and Houston (Knabb et al. 2005; Koerber 2006). Drawing on human-capital investment models of geographic mobility (Borjas 1989; Greenwood 1975, 1985), some have conceptualized the decision to return to New Orleans as an individual-level function of moving costs and rebuilding expenses, as well as other time, financial, and psychological investments associated with the relocation process (Groen and Polivka 2010; Landry et al. 2007). When the expected utility1 of living in the post-disaster location (“destination”) is greater than the expected utility of living in the pre-disaster location (“origin”), vulnerable populations’ return migration is thought to be unlikely (Groen and Polivka 2010).2 Accordingly, cross-sectional research conducted just after the hurricane indicated that New Orleans’ poorest permanently out-migrated (Elliott and Pais 2006; Frey and Singer 2006).

However, recent analyses of longitudinal survey data have found that these human-capital approaches to return migration may not hold: all else equal, vulnerable individuals—despite achieving socioeconomic gains in the post-disaster location (Graif 2012)—are likely to return to New Orleans over time (Fussell et al. 2010). Drawing on theories initially developed to explain international migration flows, this work suggests that migrant selectivity—that is, how individuals’ demographic and socioeconomic backgrounds influence return migration outcomes (Hunter 2005)—explains differences in rates of return to New Orleans between whites and blacks, though these racial disparities disappear after adjusting for Katrina-related housing damage. While a laudable theoretical first step to import theories from the sociology of immigration to the study of post-disaster return migration, the authors’ analysis does not directly assess how possible contextual and social network effects shape migration outcomes. We thus understand very little about how individuals’ subjective encounters with institutional, labor market, and social contexts manifest over time to influence the return migration decision (Tolnay 2003).

This article analyzes longitudinal quantitative and qualitative data from a sample of low-income, predominantly African-American mothers displaced by Hurricane Katrina to explain whether and how individuals make the decision to return to New Orleans, as well as the implications of this decision for neighborhood attainment. I extend the “context of reception” approach from the sociology of immigration (Portes and Rumbaut 2006) and systematize the disparate findings in the literature on how institutional, labor market, and social post-disaster contexts influence return migration decisions (see Weber and Peek 2012). In so doing, my goal is both to study the relationships between individual- and contextual-level features, and to uncover the processes underlying these relationships. How individuals encounter each dimension can affect the return migration decision (Landry et al. 2007) and, ultimately, socioeconomic mobility (Portes and Borocz 1989).

Table 1 summarizes the theoretical model of how vulnerable individuals’ interactions with institutional, labor market, and social contexts influence return migration decisions.3 When the contextual dimensions in origin are viewed as less facilitative of evacuees’ resettlement and recovery than in destination, return migration is unlikely.4 In contrast, when the contextual dimensions in destination are viewed as less facilitative of evacuees’ resettlement and recovery than in origin, return migration is likely. These ideas suggest various processes through which post-disaster institutional, labor market, and social contexts influence whether and how vulnerable individuals undertake the return migration decision.5 Specifically, I show how subjective comparisons of the three contexts between origin and destination, perceived experiences of discrimination within each context, and changing contexts over time explain my sample’s divergent migration and mobility outcomes. I conclude with implications for future research on, and policy responses to, natural disasters.

Table 1.

How post-disaster contexts influence return migration decisions

| Post-disaster context | Description | Examples of factors influencing migration decision | |

|---|---|---|---|

| More likely to return | Less likely to return | ||

| Institutional | The degree to which vulnerable individuals (a) can access local-level institutional support in origin or destination; (b) perceive these institutions as conducive to their resettlement and recovery in origin or destination; and (c) experience institutional discrimination in origin or destination | Rationalizes failed governmental response in origin in the face of unfriendly reception in destination | Perceptions of failed governmental response to disaster |

| Perceives discrimination with local institutional representatives (e.g., street-level bureaucrats) in destination due to survivor status | Experiences of racism and other forms of institutional discrimination during disaster in origin | ||

| Belief that post-disaster neighborhood is better managed than in origin (less crime and violence; better schooling) | |||

| Labor market | The extent to which members of a vulnerable population (a) can enter the labor market in origin or destination; (b) perceive themselves as employable in positions commensurate with their qualifications in origin or destination; and (c) experience discrimination in origin or destination | Expresses origin as only option for earning money | Perceives destination as facilitative of socioeconomic mobility (e.g., pay scale, lifestyle, and general well-being), relative to origin |

| Views having a job as secondary to desire to restore normalcy for children by returning home | Interprets disaster as a “fresh start” for children to achieve long-term gains in mobility | ||

| Perceives labor market discrimination associated with evacuee status | Resilient in the face of perceived labor market discrimination in long-term | ||

| Social | The extent to which vulnerable individuals (a) perceive locals in destination as ambivalent or amenable to their presence; (b) can freely compete with locals for economic attainment in destination; and (c) experience micro-level discrimination or stigmatization post-disaster that limit opportunities for mobility | Recalls interactions with neighbors in destination as unreceptive | Forms network of friends from origin in destination |

| Experiences stigmatization as “refugee” | Expresses discomfort with new social context but appreciates new environment for children’s development | ||

| Reports discomfort associated with instability due to moving over time | |||

Contexts of reception and post-disaster migration

A context of reception approach to the study of migration emphasizes how the institutional, labor market, and social features of a specific migrant-receiving environment shape newcomers’ settlement experiences and opportunities for mobility (Portes and Bach 1985; Portes and Borocz 1989; Portes and Rumbaut 2006). Similarly, how individuals encounter their new environments following a disaster-induced move influences whether they return to origin or remain in destination. In contrast to theories derived from neoclassical economics (see De Jong and Fawcett 1981; Speare 1974; Wolpert 1966), the context of reception approach comprehensively considers the post-disaster milieu within which individuals undertake the migration decision (see Phillips and Morrow 2007).6 As Gardner (1981: 88) summarizes: “The study of migration decisions, while necessarily proceeding on the micro-level, must nevertheless take into account at all steps the influence of macrofactors, the social and the institutional, the economic and the geographic context within which the individual exists” (see also Tolnay 2003). In this section, I systematize past work with respect to these three contextual dimensions to suggest the typology’s utility for understanding whether and how vulnerable individuals undertake the return migration decision, as well as the decision’s implications for mobility.

Institutional context

The post-disaster institutional context is the first dimension that influences vulnerable individuals’ migration choices. The institutional context encompasses the formally recognized sets of people, practices, and resources facilitating an individual’s post-disaster resettlement and recovery, such as schools, welfare agencies, and police departments (cf. Allard and Small 2013).7 Return migration is less likely when vulnerable individuals (a) can access local-level institutional support in destination; (b) perceive institutions in destination as conducive to their resettlement and recovery; and (c) experience institutional discrimination in origin. It is more likely otherwise.8 How amenable environmental migrants9 perceive the post-disaster institutional context to be also influences their chances for labor market and social incorporation (Portes and Borocz 1989; Portes and Rumbaut 2006).10

Vulnerable individuals are especially dependent on the post-disaster institutional context for resettlement and recovery. Low-income households are more likely to receive public assistance than wealthier ones after a natural disaster and, as such, are typically assumed to settle permanently in destination (Bates 2002). Cross-sectional quantitative analyses post-Hurricane Katrina confirm this observation, finding that those receiving public assistance are less likely to return to New Orleans since the move is cost prohibitive (Frey and Singer 2006; Landry et al. 2007). Returning to origin is thus not viewed as a migration choice available to vulnerable populations post-disaster because the financial investment required for relocation defies the logic of theories based in rational choice economics (Landry et al. 2007).

However, longitudinal surveys suggest a complex interaction between vulnerable individuals and their post-disaster institutional contexts that may expand return migration opportunities over time. In post-Katrina New Orleans, Fussell et al. (2010) show that lower return rates for poor African-Americans relative to comparable whites are driven by institutional factors, such as the former having lived in areas that experienced more severe housing damage (see also Paxson and Rouse 2008). Since the 1970s, the city’s predominantly black extreme-poverty neighborhoods have grown (Berube and Katz 2005), making African-Americans more likely to have lived in neighborhoods that experienced serious flooding relative to comparable whites (Brazile 2006). Cutter and Emrich (2006) attribute these differences to a long-term process of institutionally mediated race- and class- based residential segregation in pre- and post-Katrina New Orleans (see Massey and Denton 1993).

In spite of these institutional constraints, recent estimates reveal that 53 % of New Orleans’ pre-hurricane adult population—44 % of whom are black—has returned, with 33 % living in their pre-Katrina housing (Sastry and Gregory 2012). The most vulnerable returners are likely to settle in neighborhoods yet to rebuild from the hurricane (Seidman 2013, see also Wooten 2012), especially given a “politics of disposability” whereby government officials respond more favorably to the wealthy than to the city’s most vulnerable (Giroux 2006). Individual-level differences in family structure may compound this effect, with Murakami-Ramalho and Durodoye (2008) finding that female-led, single-parent households faced numerous challenges in accessing relief aid after Hurricane Katrina (see also Reid 2010). To my knowledge, however, no work has examined how vulnerable individuals’ interactions with the post-disaster institutional context influence their resettlement and recovery.

Labor market context

Integration in the post-disaster labor market context—the extent to which members of a vulnerable population (a) can enter the labor market in origin or destination; (b) perceive themselves as employable in positions commensurate with their qualifications in origin or destination; and (c) experience discrimination in origin or destination—is the second dimension influencing the post-disaster migration decision. Like the institutional dimension—in which perceptions of how conducive local institutions are to evacuees’ needs shape migration outcomes—actually holding a job or earning a higher income relative to origin are secondary considerations (Portes and Rumbaut 2006). Return migration is less likely if the displaced perceive labor market integration post-disaster to be possible, and more likely otherwise (Portes and Bach 1985).11

Labor market integration was difficult for vulnerable populations immediately after Hurricane Katrina, both in New Orleans and elsewhere. Elliott and Pais (2006) find that, all else equal, black workers were approximately four times more likely than white workers to report having lost their pre-Katrina jobs, a dynamic disproportionately impacting low-income blacks. Using the Current Population Survey from August 2004 through October 2006, Vigdor (2007) shows that evacuees who returned post-Katrina faced short-term negative effects on various labor market outcomes (e.g., hours worked, employment, and earnings) but fared better than non-returners (see also Zissimopoulos and Karoly 2010). In spite of these bleak labor market prospects, scholars find no association between these objective measures and individuals’ return migration (Fussell et al. 2010; Zottarelli 2008).

A growing body of work, however, suggests the importance of individual-level and subjective encounters with the labor market context in explaining how vulnerable populations make their post-disaster migration decisions. For example, the influx of low-income, predominantly African-American evacuees to the Baton Rouge, Houston, and Dallas metropolitan areas may have generated labor market competition between locals and newcomers (McIntosh 2008). Literature in urban sociology indicates that settlement in destination is unlikely if job competition impedes a disadvantaged group’s perceived ability to access the labor market, even if returning yields no increase in earnings or employment (Maxwell 1988; Smits 2001). Settlement is most likely in labor markets where skillset-appropriate, quality jobs are available (Bartlett 1997). How perceived and lived experiences of labor market discrimination may impact vulnerable populations’ post-disaster migration decisions remains to be examined.

Social context

The post-disaster social context is the final—and, over time, most important—dimension shaping migration decisions.12 Similar to the institutional and labor market contexts, return migration is unlikely when the displaced perceive the post-disaster environment as ambivalent to their presence and newcomers are able to freely compete with locals for social and economic attainment (Portes and Rumbaut 2006). In contrast, return migration is likely when the displaced are as economically disadvantaged as the locals of the same racial or ethnic background in destination. If newcomers cannot utilize their social networks to facilitate socioeconomic mobility, and if non-coethnic locals are perceived as holding stereotypes about the displaced that limit their opportunities for mobility, return migration is also likely (Portes and Borocz 1989).

Relying on kinship networks to facilitate their recovery (Hunter and David 2011; Hurlbert et al. 2000), and reflective of a growing body of work that examines the gendered dimensions of migration (Curran et al. 2005, 2006), vulnerable populations—especially low-income African-American mothers—are disproportionately affected by these social processes post-disaster (Enarson 1999). Paxson and Rouse (2008), drawing on the same dataset as this article, find that flood exposure influences return migration to New Orleans 1 year after Katrina but, among those who were not flooded, not owning a home in origin and regular church attendance in destination made return migration less likely. Returning to New Orleans is not an option immediately available to all evacuees, however. Neighborhood-level recovery occurs more quickly in communities high in material and social resources than in those lacking such assets (Aldrich 2012), especially given the former’s high levels of community engagement post-disaster (Kage 2011). Due to the stigmatization of temporary housing meant to accommodate New Orleans’ most vulnerable populations post-Katrina (Aldrich and Crook 2008), residents of more advantaged communities exhibit high levels of social cohesion and may mobilize to restrict the number of available housing options for vulnerable individuals (Davis and Bali 2008).

How individuals interact with the social context in destination is also likely to influence vulnerable individuals’ long-term migration outcomes. Hopkins (2012), examining reactions to displaced newcomers in Houston, finds that once-altruistic attitudes toward African-Americans and the poor post-Katrina hardened several years later (see also Aldrich and Crook 2008). He attributes these shifts to the interaction of frames about evacuee benefits, joblessness, and criminality with changes in local demographics (Hopkins 2012: 444). Reflective of larger regional and national trends (Waters et al. 2014), the sudden and sustained growth of multiracial (Kates et al. 2006) and multiethnic (Fussell 2009) communities post-Katrina may have attenuated social cohesion due to perceptions of economic and racial threat (Hopkins 2012). In such cases, Enarson (1999) argues that vulnerable individuals may experience feelings of social isolation or other constraints (e.g., insufficient childcare) that make return migration more likely. Initially, warm post-disaster social environments may thus become hostile over time.

Analytical strategy

Data

I use data from the Resilience in the Survivors of Katrina (RISK) Project, a mixed-method, longitudinal study collected over 6.5 years. Participants were initially part of a randomized-controlled evaluation of Opening Doors Louisiana, a scholarship and counseling program designed to increase the educational attainment of students at three Louisiana community colleges. Eligible respondents were between 18 and 34 years old; the parent of at least one dependent child; had family incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty line; earned no prior college-level credits; and were willing to attend college at least halftime.13 Given these requirements and the colleges’ catchment area, the majority of study participants are low-income, African-American mothers receiving public assistance. At baseline (November 2003–February 2005), the RISK Project surveyed 942 low-income mothers who intended to enroll in community college (see Richburg Hayes et al. 2009).

In late August 2005, Hurricane Katrina disrupted the community college intervention, shutting down the Opening Doors campuses; the project transformed into a longitudinal study of how vulnerable individuals and their families recover in the wake of a natural disaster. Two more survey rounds were conducted from March 2006 to March 2007 (Wave 2) and from March 2009 to April 2010 (Wave 3). Each survey included questions pertaining to health resources and outcomes; social resources and outcomes; and child well-being. Respondents’ residential locations before and after the hurricane were recorded and geocoded at each wave.14

I rely primarily on the qualitative component of the project, which was informed by previous analyses of survey data that revealed heterogeneity in survivors’ mental health outcomes and residential locations post-Katrina (see Lowe and Rhodes 2013).15 In late 2006 and early 2007, a diverse research team16 purposively selected 57 respondents who had completed Wave 2 of the survey for the first round of qualitative life history interviews. Round 2 of the life history interviews was conducted at the same time as Wave 3 of the survey with a subsample of 48 additional respondents. Finally, 20 respondents from the first round of qualitative data collection were re-interviewed between August 2011 and 2012.17 In all, the RISK Project includes 125 interviews with 105 women. I focus on a final sample of 120 interviews with 100 women for whom complete residential histories are available. The qualitative subsample is representative of the full survey (Table 2). The semi-structured interviews lasted 1–2 h and addressed topics similar to the full survey.

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic characteristics of full survey sample to qualitative subsample

| Baseline (N = 1,019) | Qualitative subsample (N = 105) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Female | 942 | 0.924 | 105 | 1.00* |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 103 | 0.105 | 5 | 0.048 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 838 | 0.851 | 89 | 0.848 |

| Hispanic | 26 | 0.026 | 6 | 0.057 |

| Other | 18 | 0.018 | 1 | 0.010 |

| Missing | 34 | 0.033 | 4 | 0.038 |

| Age | 1019 | 25.31 (0.14) | 105 | 24.74 (0.40) |

| Household characteristics | ||||

| Number of children | ||||

| 1 | 516 | 0.509 | 58 | 0.552 |

| 2 | 276 | 0.272 | 26 | 0.248 |

| 3 or more | 222 | 0.219 | 21 | 0.200 |

| Living with partner | 146 | 0.146 | 11 | 0.105 |

| Household size | 984 | 3.65 (0.04) | 100 | 3.54(0.13) |

| Baseline income/resources | ||||

| Most recent hourly wage | 960 | 7.08 (0.10) | 99 | 7.38 (0.62) |

| Public benefits | ||||

| Unemployment | 44 | 0.044 | 7 | 0.067 |

| Social security insurance | 131 | 0.132 | 16 | 0.152 |

| Cash assistance | 103 | 0.103 | 16 | 0.152 |

| Food stamps | 616 | 0.618 | 73 | 0.695 |

| Public housing/section 8 | 162 | 0.180 | 13 | 0.148 |

| No benefits | 243 | 0.276 | 19 | 0.218 |

| Currently employed | 523 | 0.514 | 50 | 0.481 |

Pearson’s chi-square test for distributions and t test for difference in means between responders and nonresponders were conducted and were not significant

Sums of means within categorical variables may be greater than 100 due to rounding

p < .05

Methodology

Wolpert (1966) and Speare (1974) consider stayer–mover models in which stayers remain in origin and movers outmigrate in response to environmental stress. Given respondents’ migration choice in this article—whether to return to New Orleans after initial displacement—I investigate a slightly different pattern and compare “movers” (displaced respondents who have not returned to, and currently reside outside of, New Orleans by the study’s final wave) and “returners” (displaced respondents who have returned to, and currently reside in, New Orleans by the study’s final wave).18 Difference-in-means tests reveal no significant differences between movers’ and returners’ observed demographic characteristics at baseline (Table 3).19

Table 3.

Comparison of demographic characteristics of returners and movers in qualitative subsample at baseline

| Returners (N = 56) | Movers (N = 44) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Female | 56 | 1.00 | 44 | 1.00 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 4 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 42 | 0.79 | 43 | 0.97 |

| Hispanic | 6 | 0.11 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Other | 1 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Missing | 3 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.03 |

| Age | 56 | 24.73 (4.09) | 44 | 24.70 (4.25) |

| Household characteristics | ||||

| Number of children | ||||

| 1 | 32 | 0.57 | 23 | 0.52 |

| 2 | 15 | 0.27 | 11 | 0.25 |

| 3 or more | 9 | 0.16 | 10 | 0.23 |

| Living with partner | 6 | 0.11 | 4 | 0.10 |

| Household size | 52 | 3.35 (1.23) | 43 | 3.67 (1.19) |

| Baseline income/resources | ||||

| Most recent hourly wage | 51 | 6.78 (2.57) | 43 | 8.11 (8.90) |

| Public benefits | ||||

| Unemployment | 4 | 0.07 | 3 | 0.68 |

| SSI | 7 | 0.13 | 8 | 0.18 |

| Cash assistance | 7 | 0.13 | 7 | 0.16 |

| Food stamps | 37 | 0.66 | 33 | 0.75 |

| Public housing/section 8 | 5 | 0.09 | 7 | 0.19 |

| No benefits | 39 | 0.70 | 37 | 0.85 |

| Currently employed | 22 | 0.39 | 25 | 0.56 |

Pearson’s chi-square test for distributions and t test for difference in means between responders and nonresponders were conducted and were not significant

Sums of means within categorical variables may be greater than 100 due to rounding

Total N excludes five respondents for whom final residential location is unknown

Although I wanted to understand why some respondents selected into returning to New Orleans (“returners”) while others remained in the post-disaster context (“movers”), I did not code the data with any preconceptions about what I might find. I instead adopted an inductive and iterative approach that allowed me to explore themes that emerged organically from my analysis of returners and movers (Glaser and Strauss 2009). Respondents were not always asked explicitly about their return migration decisions; as such, this analysis encompasses their responses to several questions regarding family structure, neighborhood quality, social networks, and health care, among other topics.20 I first read all the interviews in order to acquaint myself with the data and then followed Miles and Huberman (1994) to generate a list of themes related to respondents’ migration choices. I placed these codes into broader categories—institutional, labor market, and social contexts—because I found these dimensions to be the most analytically meaningful. I then reanalyzed the data with this framework in mind and noted how a respondent explained having made her return migration decision. Importantly, I discovered that a context’s objective causal efficacy—that is, whether it is good or bad according to objective measures such as having a high income and low levels of violence—was a secondary consideration for respondents (see Mills 1940). Rather, how individuals interacted with each context factored more heavily into whether and how she chose to return to New Orleans.

At the end of this process, a research assistant reviewed my coding in order to ensure results’ accuracy and consistency. We adjudicated disagreements together before finally calculating an inter-rater reliability score (i.e., the total number of agreements in coding divided by the total number of comparisons) to be approximately 95 % (Miles and Huberman 1994). This type of inductive coding is especially important for researchers interested in understanding how different contexts shape individuals’ behaviors (Maxwell 2012), allowing the discovery of causal processes leading to an outcome (in this study, return migration or not) (Maxwell 2004).

In the presentation of findings below, I first use a method of data reduction to take a birds-eye view of the qualitative data (Ragin 1989).21 Doing so reveals what contextual encounters shape returners’ and movers’ migration choices. I then present more in-depth analyses from the interviews to illuminate how individual-level interactions with institutional, labor market, and social dimensions factor into how respondents made the migration decision.

Findings

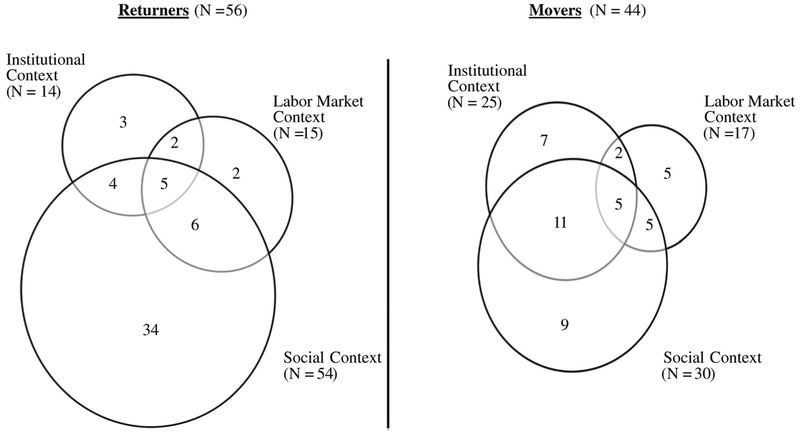

How vulnerable individuals encounter post-disaster institutional, labor market, and social contexts influence return migration decisions. My analyses of 120 interviews with 100 low-income, predominantly African-American mothers reveal that all respondents weighed at least one of these dimensions—which are comprehensive but not mutually exclusive—when making the post-disaster migration choice; movers and returners experienced these contexts differently, however (Fig. 1). While both returners (N = 56) and movers (N = 44) most often reported social factors as shaping their decision to return to New Orleans, movers’ motivations tended to exhibit greater overlap across two or more contextual dimensions than did the returners’. Within institutional, labor market, and social contexts, the results below suggest respondents’ comparisons between origin and destination, their experiences of discrimination post-disaster, and changing contexts over time help to explain divergent migration and mobility outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of institutional, labor market, and social dimensions underlying respondents’ post-disaster migration decisions in rounds 1 and 2 of interviews, by migration status (N = 100)

Institutional contexts and return migration

How individuals interact with post-disaster institutional contexts is the first dimension impacting migration outcomes. Return migration is less likely when vulnerable individuals can access local-level institutional support in destination, perceive these institutions as conducive to their resettlement and recovery, and experience institutional discrimination in origin; it is more likely otherwise. While 39 of 100 respondents explained the importance of the institutional context to the post-disaster migration decision, differences in how individuals experienced it distinguished the process by which someone became a mover or returner.

Movers and returners made explicit comparisons of institutional contexts in both origin and destination when explaining how they undertook the migration decision. For movers, resettling in less violent, wealthier neighborhoods represented an opportunity to escape from an increasingly racially and socioeconomically segregated New Orleans. Reflecting their status as mothers, respondents credited their better post-disaster neighborhoods for liberating them from the shootings that occurred “two to three times a week in New Orleans,” as well as shielding their children from other negative consequences associated with living in concentrated poverty (see Massey and Denton 1993). Penelope,22 a mother of two who settled in a suburb of Houston after Hurricane Katrina, expressed fond thoughts about how much “nicer” her new neighborhood was for her children in terms of schooling and neighborhood safety, even if she and her husband would have preferred to live in New Orleans:

[T]he first thing me and my husband decided [was that] we could have lost our kids. We all could have just died. To go back there [New Orleans] now would be for our own selfish reasons and we have kids to think about. The schools are not ready for kids. They get a better education here. The area that we are in [is] safer. To be honest with you, if I didn’t have kids, I’d probably be right back in New Orleans. But I have kids and I have to think about them first before me.

Another mover, a mother of 5 named Tania, similarly explained that Houston offered more opportunities than New Orleans for mobility, especially for her children:

[Interviewer: What do you think about Hurricane Katrina?] I think the hurricane was a bad thing, but at the same token, I feel like, would I have ever left? Or would I have just been stuck in this trap? To me, New Orleans is a trap, a bondage place, especially when you get out and you see it’s so much better [here]. I mean, my kids have brand new schools. The schools are huge. They’re like a college campus. They have a 20-to-1 teacher ratio. They’re excited about school. It’s not boring, It’s not ghetto and all the other stuff that New Orleans had. […] All of that plays a major factor in me staying here because I know they’re getting a good education. […] These are opportunities that I doubt my kids would ever have in New Orleans.

In contrast to movers, the sample’s 56 returners reported difficulty accessing institutional support in destination. For example, Piper, a mother of two who moved to Texas in June 2006 but ultimately returned to Louisiana, described how her decision to return to New Orleans was based on her negative interactions with government institutions in Houston. Finding these agencies to be “rude” and that “[t]hey didn’t want evacuees there,” she recalled the “nasty comments” she overheard when applying for welfare benefits:

I was in the family support center one day, the place where you get food stamps and Medicaid. They had this one lady, she was working behind the desk. She was talking to somebody else that was from Houston, not knowing who is from New Orleans and who is from Houston. She said, “I hope these damn evacuees go back where the hell they came from.” They say stuff like that. When I had the first opportunity to come back to Louisiana, I came back.

Respondents described similar sentiments with other local institutions in destination. Phoebe, who also left Houston for New Orleans, complained that the police were just as unreceptive to Katrina evacuees. When she discovered that her apartment had been burglarized and reported the crime, officers allegedly told her, “Well, maybe it was just one of your own people [who] did it.” Returning thus represented an opportunity for respondents such as Piper to feel “more comfortable” in interacting with the local institutional context since its representatives “endure[d] the same things that the [displaced] people were enduring.”

Whether and how movers and returners experienced institutionally mediated discrimination after the storm also determined how a respondent made the decision to return to New Orleans. Respondents were more likely to resettle outside of New Orleans if they felt that government institutions “didn’t care about us” as they sought to recover during and post-Katrina. The sample’s 44 movers described encounters with racism and other acts of discrimination before, during, and immediately after the storm. Prudence, a lifelong New Orleans resident who was unable to evacuate before Katrina and sought shelter with her three children in the Convention Center, criticized all levels of government—from then-President George W. Bush to then-Governor Kathleen Blanco to then-Mayor Ray Nagin—for mishandling the local response to Katrina. She moved to the Dallas Metropolitan Area, where she perceived local officials to be more accommodating of the displaced. In her own words, New Orleans officials needed to “be out there the next day…trying to rescue people.” Rebekah, a mother of 3, echoed this sentiment. She described Houston as a “good environment for my kids. The police be around [my neighborhood in New Orleans] all day now. It’s nowhere for a kid to play or grow up.” She blamed these unsatisfactory conditions on a lack of local-level support to recover from Hurricane Katrina: “[FEMA] is not helping the people. […] They not helping people who want to come home and who was here trying to get the properties there back up and running. They not doing enough for them. Like, other people coming from organizations and out-of-town just to help.”

Returners did not necessarily view New Orleans as more institutionally supportive than contexts such as Dallas or Houston. Rather, most returners emphasized their desire to “just get back to normal” after the hurricane. Clara, a mother of 1 who returned to New Orleans from Dallas, was initially motivated to return because her husband resumed work with his previous employer. She expressed relief at being back home after 2 years’ displacement but ultimately detailed her frustration about having returned because of what she perceived to be high levels of institutional corruption that impeded her access to recovery benefits:

[Interviewer: What do you think was the hardest thing for you about Katrina?] The hardest thing is not receiving any help, and you are very [looked down upon for] asking for it and applying for it. […] We’re putting dime-by-dime into fixing our home for us, so the hardest thing is not receiving any help. When you are applying for it, you get turned down. When you are asking for it, you get put on a four months waiting list. […] [This money] is for the people. It was entitled for the people. We are one of those people. When we apply and you turn us down, then who is the fund for? That’s one thing I really don’t like about right now: the corruption here in New Orleans.

Clara further explained this corruption as constraining her children’s mobility prospects: “We see scenes [of] people fighting. I know that’s present everywhere, but I worry about that. There’s a lot of corruption here. We’ll never get anywhere here. My children will not have a chance here unless we win the lottery; then we can [move up].”

Monica, a mother of 2 who moved back to New Orleans from Houston, also felt her migration choice constrained, and opportunities for mobility limited, given her difficulties in accessing institutional support in origin:

[Interviewer: How is it being back in New Orleans?] Stressed. Because nothing is open. We have nowhere to go to stop or to get food. Insurance companies aren’t helping us. It took us forever to get a [relief] check, so we had to pay for renovations out of our own pockets. I didn’t want to come back [from Houston], but I was obligated to because of this house. If I wouldn’t have had this house, I would have been better off. I wouldn’t have had to worry about anything. I could have just started over. But I was obligated to come back and start over here. And they weren’t helping to start over the process. Nobody was.

For respondents who felt their migration choices constrained—either because of employment in origin or home ownership (Fussell and Harris forthcoming; Merdjanoff 2013)—returning to origin was a necessary but not ideal reality.

Labor market contexts and return migration

How individuals interact with post-disaster labor market contexts is the second dimension shaping the return migration decision. A vulnerable population is less likely to return to origin if it can access the labor market in destination; perceives itself as employable in positions commensurate with its qualifications in destination; and experiences discrimination in origin. Return migration is more likely otherwise. For 32 of the low-income, predominantly African-American mothers in my sample, individual-level encounters with the labor market context influenced whether and how a respondent decided to return to New Orleans or settled elsewhere.

As with the institutional dimension, movers and returners compared the labor market context in destination to that in origin. Having been displaced to areas with more prosperous labor markets, movers saw little room for socioeconomic mobility in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Several respondents, who had wanted to move out of New Orleans before the storm hit, explained that the hurricane prompted them to do so earlier than anticipated. Grace, a mother of 5 whose employer helped to finance her move to Houston, mentioned that Katrina “just pushed the issue” of moving. Though “bored” at home and unemployed, Grace did not perceive the labor market in destination as unreceptive; rather, she described how it did not pay to work in Houston given its more expensive childcare rates relative to New Orleans:

The way with the day care programs out here for low-income families, it’s a little bit different than in New Orleans. In New Orleans, you can go to the Office of Family Support and apply for assistance and get it within 30 days. Down here, it’s like a five to six month waiting list, and the prices of the daycares out here are more expensive. In New Orleans, I was paying $60 to $85 a week. Down here, it’s like $140 or $150 a week. So, with the programs and the cost of living, it just pays to be home because, if not, you’ll be working to pay childcare, and that defeats the purpose of working. So, I’m home with the kids.

Patricia, a mother of 2, also compared origin to destination, recognizing that her displacement to Dallas offered greater opportunities for mobility than New Orleans. She explained that she “wasn’t happy with the pay scale [in New Orleans]. I was not happy with the school system, the crime…. I knew that, as my kids got older, it was going to get worse, and I wanted them to have a different life.” Nikita, a mother of 1 who settled in Houston, concurred. She viewed the storm as an opportunity only available in destination to achieve mobility:

Katrina was a good thing for some people and a bad thing for others. [I]t was a good thing for my family…[b]ecause, if it wasn’t for Katrina, we probably would still be in New Orleans, not knowing that there is something better. […] And for me, my job now, the benefits are much better, the pay is better. I mean, just overall, my whole lifestyle has changed for the better. I mean, and if it wasn’t for Katrina, I would still be actually in New Orleans doing what I was doing, making the same money and just content.

Concurring with Nikita, Chantelle, a mother of 1 who was a paraprofessional educator in New Orleans, juxtaposed the labor market opportunities available in New Orleans to those in Dallas:

[Interviewer: What type of jobs are available here that aren’t available in New Orleans?] I would say like with the call centers and stuff like that. Like, call services with Sprint. The banking. The big corporations that has their major centers here where you can go in and work. We don’t have that in New Orleans. It’s just like either you teach or you do something in the medical field. There’s not really a wide spread that you can choose from. You know? I mean, in Saint Charles Parish, we have a couple of chemical plants but other than that, I don’t see big major corporations there. Maybe I’m wrong, but I just don’t see it there.

In contrast, respondents were more likely to return to New Orleans if they felt the post-Katrina labor market to be unreceptive to their presence. Kimberly, a mother of 2, described being excluded from the job market in Houston because of her evacuee status:

That’s the perception I was starting to take on. As soon as they find out you’re from New Orleans—like anything, your credentials, your educational background, your experience—it had no bearing. Just as you came from New Orleans, they had pretty much pre-judged you. [Interviewer: How could you tell?] I went to an interview… and I mean, it was something like a customer service position. I had been doing customer service at Best Buy since 2001. So, I had that experience. I had references. I have some school background. We had a good interview. The lady was enthusiastic about hiring me. When they took me to my next interview, the gentleman and I began to talk; he found out I was from New Orleans and I never heard back.

Shaina, a mother of 4, returned from Houston for similar reasons: “Three weeks ago [I came back] because I couldn’t find a job out there. Nobody would hire me so I came home to find a job, which I did.” Tania, the mother of 5 from above, explained how returners attributed this inability to access the labor market to discrimination against New Orleans evacuees. She noted that, “once [employers] look on your résumé and see your jobs are from New Orleans, their whole attitude changed.” She continued:

And it really got to me because I felt that wasn’t fair. They would make statements like, “Well, we hired people from New Orleans, and they quit or ran back,” or something like that. And I’m like, “But everybody’s not that way. And I think that’s unfair for you to say, ‘Well, because I hired this person and he quit. And you’re from there, so you might do the same thing.”‘ I went through that a lot. […] I’ve never been arrested. I’ve never been fired. So there was no other reason for me not to get this job that you say I was definitely qualified for.

When respondents perceived opportunities for mobility to be blocked in destination, the benefit of returning to origin—where “the rent [has gone] up and the income not,” in Shaina’s words—represented the only viable alternative.

Social contexts and return migration

How individuals experience post-disaster social contexts is the final dimension influencing migration outcomes. Return migration is less likely when a vulnerable individual perceives locals in destination as ambivalent or amenable to their presence; can freely compete with locals for economic attainment in destination; and does not experience micro-level discrimination or stigmatization post-disaster. It is more likely otherwise. This feature was the most commonly mentioned context, with 84 respondents suggesting its role in the return migration decision.

Comparisons between social contexts in origin and destination emerged as respondents explained whether and how they chose to return to New Orleans. While movers preferred the social context in origin to that in destination, return migration was less likely for those who resettled in neighborhoods with other evacuees from New Orleans. Eva, whose church paid for a flight to Houston, explained unprompted how resettlement was complicated by an unreceptive social context replete with people who are “ruder” than those in New Orleans:

[Interviewer: Did you have trouble sleeping?] Definitely, sleep was a problem. […] But I would say it would probably be linked to that tearing away from family and what happened in the storm. And out here, people are…kind of rude. They’re not kind of rude; they are rude. Out here, people are rude. I mean, we’ve found friends and we’ve made a network. […] Actually, the people that we made friends with and networked with are all originally from New Orleans or Louisiana. And I guess you’re drawn to people who are more like you, because other than that, Houstonians are rude. So, I kind of went through a little transitioning problem and I never really transitioned.

Noel, a mother of 2, also expressed concerns about differences in social contexts between Houston and New Orleans. She recognized that a “different setting [brought on] different rules,” which complicated her resettlement:

Back in New Orleans, you can do whatever you want to do when you want to do it. Out here is so many rules and people tell you what to do, when to do it, and how to do it, even though you’re not even incarcerated. Going to the store, even if you are a person that drinks, you have to do it by a certain time. There’s a lot of things out here that you can’t do that you could do at home.

Although she might have compared her new Houston environment to being “incarcerated,” movers like Noel resolved to stay there because “it’s better for me and my kids.” Other movers also linked settlement in destination to their children’s opportunities for mobility. As Sara, a mother of 3, summarized when explaining how she decided to settle in Houston post-Katrina:

I’m just thinking about my children, the welfare of my kids, because basically, if I didn’t have them to think about, I could fend for myself. You hear me? But, I mean, it’s all about my kids and them growing up right and having healthy lives so they can be productive adults when they get up on their own. You know, so they don’t have to struggle like I had to struggle.

For respondents who perceived settlement in destination as conducive to their children’s mobility outcomes, then, return migration was unlikely, even if the post-disaster context was unreceptive.

Whether and how movers and returners experienced discrimination in the social context post-Katrina also influenced the return migration decision. Individuals were more likely to resettle outside of New Orleans if they lived initially among a network of like-minded survivors who “understood what we all went through.” Such was the case for Geneiece, a mother of 3 who moved to an apartment complex in Houston: “[We live in] a newer apartment complex actually. […] It has like three families staying there, but we’re like the fifth from New Orleans to move in. Everybody from New Orleans started moving in. [FEMA] helped people move in from shelters.” Living among other survivors reminded many respondents of “being back in New Orleans.” As Phoebe explained, “New Orleans is more of a party type atmosphere. [The evacuees] would bring this to Texas—like the hanging out all the time of night and listening to music.”

In contrast to movers, respondents were more likely to return to New Orleans if they felt the social context in destination to be entirely unreceptive to evacuees. Some described experiencing discrimination in their new neighborhoods. For example, Amy—who kept to herself in Baton Rouge post-Katrina—explained how she felt that her status as a Katrina survivor led one of her new neighbors to consistently harass her:

[This] one lady—and I guess it was because of all the things that she had heard on the news about New Orleans people—was saying about how they keep the area clean and they don’t like loud music. […] But it’s like she kept bothering me…. And, I’m like, I’m not like that, but she kept bugging me. And so, one day I just went off, and she said I hurt her feelings. I was staying to myself and staying inside…. I didn’t bother anybody, but it was just a constant thing of, “We don’t like loud music,” and I only had a little bitty radio, like an alarm clock. That’s it. It was just a constant thing.

Other returners also reported feeling stigmatized in destination because of their New Orleans roots and status as Katrina evacuees. In particular, respondents rejected their stigmatization as “refugees.”23 Natasha, a mother of 4 who returned to New Orleans from Dallas, viewed this label as relegating evacuees to “foreign” status:

We label everything in this country. The first thing they said was that—when people went [to Dallas]—the “refugees” are from New Orleans. Now, living in this country all these years, you assume refugee means a person from Haiti or a person from Cambodia, a person from Vietnam, a person from Africa that snuck in this country, you know, Cuba, anywhere but this country. You never thought for a minute you are going to be labeled as a refugee and you live in this country.

Feelings of stigmatization associated with the “refugee” label ostracized many respondents in destination. Marisa, another respondent who had originally evacuated to Dallas before returning to New Orleans, described how she grew “tired of feeling like I’m begging people for something. Like, they call us so-called refugees.” Leaving Dallas represented the most productive decision for Marisa: “I don’t have time to keep traveling different places and trying to find food and water…. I’m going back to work [at my previous job], and my husband and I will just buy what we need.” Returning to a more receptive social context may thus lower the social costs associated with resettlement for vulnerable individuals displaced by a natural disaster.24

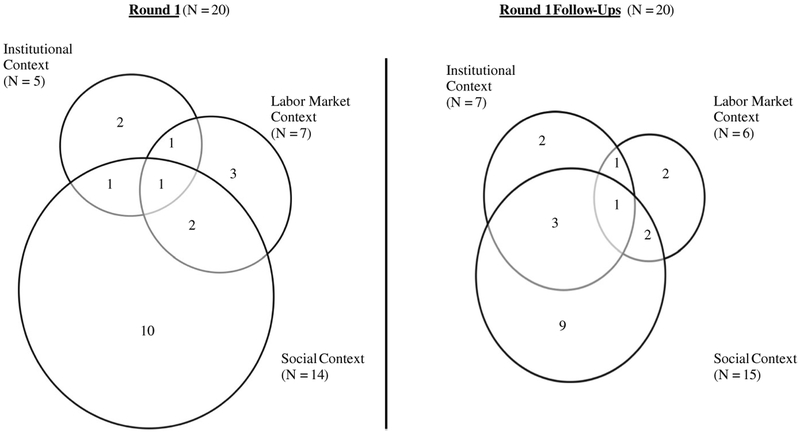

Changing contexts over time

While the cross-sectional interviews reveal how individual-level encounters with institutional, labor market, and social contexts influenced a vulnerable populations’ return migration decisions in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the longitudinal data shed light on how these dynamics evolve over time and their implications for mobility. By the final wave of the study, movers lived in census tracts that were, on average, less impoverished than the returners (Table 4).25 Comparisons of the 20 respondents who completed two rounds of interviews reveal that social factors continued to be the most likely explanation for whether and how respondents chose to return to New Orleans, though some combination of all three dimensions continued to be salient (Fig. 2). The relative stasis in the prevalence of institutional, labor market, and social contexts in respondents’ decision-making processes suggests their importance for the return migration decision over time.

Table 4.

Comparison of returners’ and movers’ tract-level poverty in full survey at baseline and at final wave

| Baseline (2003) | Wave 2 (2009–2010) | |

|---|---|---|

| Returners (N = 295) | 0.26 (0.14) | 0.22 (0.13) |

| Movers (N = 165) | 0.24 (0.13) | 0.19 (0.13) |

| p = .18 | p = .03 |

Standard errors in parentheses. t test for difference in means between returners and movers at baseline, wave 1, and at the final wave conducted. The same tests were conducted for responders and nonresponders and were not significant

Source: Author’s calculations of 2000 and 2006–2010 American Community Survey and RISK Project data

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of institutional, labor market, and social dimensions underlying respondents’ post-disaster migration decisions in round 1 and round 1 follow-up interviews, by interview wave (N = 20)

Although movers and returners were not asked about what factors predicted return migration, the longitudinal interviews reveal that those who exhibited greater resilience in the face of difficult post-disaster contexts were less likely to return to origin. As above, how respondents interacted with post-disaster institutional contexts shaped their migration decisions. Hannah, a mother of 1 who evacuated to Houston, highlighted the precariousness of depending on government institutions for resettlement and recovery after Hurricane Katrina:

About two weeks after the hurricane, we got assistance from FEMA. Right now, everything is OK, but nothing is permanent. Like, in New Orleans, nothing was guaranteed, but you had a permanent status. You had a job. You had a house. You had a car. You knew next week was your pay week. Out here, it’s like, I got a job, but I’m living in this apartment and FEMA is paying for it. FEMA might say tomorrow we don’t have any money left. You got to move.

This residential instability is further exacerbated by time limits on eligibility for disaster benefits. Hannah reported that several of her acquaintances’ benefits ended suddenly, making it difficult for these individuals to make ends meet each month since “the cost of living is much higher out here [in Houston] than in New Orleans; the rent is much higher out here.” As was the case for Hannah’s brother, return migration to New Orleans was likely for vulnerable individuals whose benefits expired before they had achieved labor market integration.

These sudden changes in the receipt of institutional support thus have the potential to spill over into other aspects of post-disaster recovery. In particular, Hannah recalled how difficult finding a job was when she first arrived in Houston. Employers were reluctant to hire people they viewed as likely to return to New Orleans once housing vouchers expired:

Once you say you are from New Orleans, they didn’t want to hire you. Actually, one supervisor [told me] they are not going to hire you. He said, “I’m going to do the interview and go through the motions but they are not going to hire you.” And I was like, “Why?” He said because they know as soon as New Orleans gets fixed up, everybody is going back and they don’t want to hire people and they will quit on them. To this day, I know people from New Orleans and they can’t get a job. It’s not because they don’t want jobs, but people won’t hire them. And especially the vouchers expiring.26 They think they are going to leave.

In contrast to the returners described previously—such as Kimberly, whose experiences with labor market discrimination in Houston prompted her return to New Orleans—Hannah resolved to stay in destination. She conducted a 5-month job search and ultimately found a job at a mobile phones retailer. She grew to be satisfied with her new position, an opportunity unavailable to her in New Orleans given the large numbers of returners competing for limited jobs:

I’m not going to say the jobs out here are better, but they have more. Like, in New Orleans, if you work for a charity or the state, it was so hard to even get [those jobs after Katrina]. Out here, the opportunity is more open. In New Orleans, they had too many people to fill up the jobs that they had. That’s why a lot of people didn’t have jobs. But out here they have a lot of job opportunities. You just have to look for it or know somebody that knows something.

For returners, however, accessing the labor market in destination represented too impossible a feat given intense competition from other displaced survivors. Shaniece, a mother of 3 who ultimately returned to New Orleans from Dallas, explained that she first wanted to go back because “[Dallas is] too big. It’s too competitive. There’s too many people from here that are there now.” In a second interview, she explained that, “In hindsight, I wish I would have stayed [in Dallas]” because New Orleans is stalled economically:

It’s not the same down here [in New Orleans]. We’ve been down here for three years and it’s getting worse. There’s nothing for my children to do. When we were out there [in Dallas], we really enjoyed ourselves. For me, now, there’s [no work] to do. There are no after school activities. […] Texas had a lot to offer.

Movers who remained in destination may thus have been able to achieve greater access to labor market opportunities over time than individuals who returned to New Orleans in the short term.

Longitudinal interviews with vulnerable individuals also reveal shifting dynamics associated with labor market discrimination. A mother of 1 named Rose, who was unemployed during the first round of post-Katrina interviews in Houston, explained that an initial influx of evacuees in the receiving labor market might have generated tensions between locals and newcomers. She described hearing from friends that “[people from New Orleans] came here with an attitude and everything…and cursed [the locals] out” as they adjusted to their new environment. These initial hurdles to labor market integration may be overcome in the long term, however. Holding a job at the follow-up interview, Rose noticed a marked shift in the labor market dynamic between newcomers and locals:

It’s crazy! They do treat you differently [because you’re from New Orleans]. It’s like, I’ve only been at this job for a year, and when I first started working there, I noticed that everybody kinda gravitates toward the new person, and then when they hear my accent, they immediately know I’m from New Orleans, and then that’s it. They’re not that curious or interested anymore.

Other respondents echoed Rose’s observation of locals’ waning curiosity. Eva, the mother of 2 who settled in Houston after Hurricane Katrina introduced previously, similarly described her coworkers’ initial curiosity to her presence as driven by a distinctive New Orleans accent:

[Interviewer: How often do you think about what happened because of Hurricane Katrina?] Probably every day. When I say every day, we’re always reminded, especially at work [because] “people from New Orleans” or the “New Orleans people” talk funny. Like, we’ve got an accent, so then of course that reminds you of why you’re here.

As locals on the job became accustomed to Eva’s way of speaking, however, fewer of these conversations took place because “nobody cares anymore [about] Katrina.” In this way, labor market integration may be possible over time.

Rose and Eva’s experiences stand in stark contrast to individuals who chose to reenter the New Orleans labor market. After initial displacement, the predominantly black-white New Orleans became increasing multi-racial, a process driven by the arrival of Latino laborers (Fussell 2009). Most returners saw Latinos’ presence as largely innocuous along labor market dimensions, viewing their recent arrival as an extension of their own post-Katrina experiences. As Kelly, a mother of 1 who returned to New Orleans from Houston, described:

[Interviewer: What do you think about the immigrants going to New Orleans?] I don’t really have thoughts on it. It don’t really bother me. I guess it’s more or less like I feel like everybody should be given some type of opportunity, and if that’s the way you’re getting your opportunity, that’s just like people might feel [about] people from New Orleans. I mean, we were looked at like immigrants coming to a certain place. Different states looked at us like, “What are you doing here? Why are you here?” So I can’t really look at them like they shouldn’t be here because a lot of people felt the same about us.

But some respondents argued that the increase in low-wage labor “makes it harder for people to get jobs.” Taylor, a mother of 2 who returned from Houston, New Orleans’ changing racial composition generated labor market competition since Latino laborers usurped construction jobs from New Orleans natives by doing work for “cheaper than regular contractors” (Fussell 2007).

In addition to changing institutional and labor market contexts, movers and returners noted shifting dynamics in the post-disaster social context over time. Movers, who lived in more racially diverse neighborhoods for the first time after Katrina, initially adjusted to their new neighbors with difficulty. Grace, the mother of 5 introduced previously, lived in a “mixed” neighborhood. When asked about her neighbors, she noted how little she interacted with them:

Sometimes it’s a little hard because I always assumed that, when you bought a home, you would be close to your neighbors from what you see on TV and from what I’m used to [in New Orleans]. Everybody knew everybody. But down here, it’s like they look at us like we are the minority or something. Both sides of my neighbors are Hispanic. Every now and then I’ll wave at them, and they’ll just look. It feels funny.

Other movers concurred with this assessment, but all agreed that “[if] they don’t bother me, I won’t bother them,” in Nikita’s words. Over time, however, movers like Grace adjusted to living in their racially diverse neighborhoods and even grew to trust their new neighbors. As Grace described, “My neighbors on the right are a pretty nice Hispanic couple with two teenage kids. They’re fairly nice. They kind of look out for you, and you kind of look out for them.”

Returners’ resettlement experiences in New Orleans were similarly dynamic over time. Kristin, a mother of 1 who returned to New Orleans from Dallas, described that “going home” “still [represented] a new place to live” because “it’s not going to be the same. A lot of stores are not coming back. A lot of people aren’t coming back.” Other returners agreed, with Karen recounting her own challenges with readjusting to the city after moving back from San Antonio:

[Interviewer: What were the greatest losses you suffered?] One is that you can say mental stability…because you’re setting out there, you only have so much money to your name, you don’t know what you’re going to do, how you’re going to do it, how you’re going to take care of yourself, your children. You’re just being pulled out of your natural roots, basically, like a tree. You pull a tree out and the natural roots is not going to know [how to grow].

Some respondents attributed part of this “new place to live” mentality to their realization that Hurricane Katrina fundamentally altered the city and its inhabitants. As returners such as Shaniece noted, resettlement and recovery is a slow process:

[Interviewer: Do you think about Katrina a lot?] I would say maybe once a month. […] You see this person isn’t home and that person isn’t home. They are working on this house or that house. My family…always takes a ride to the lakefront on Saturday nights, and on our way there, you see that big X on the house. The houses are still just sitting there, with nothing done [to them].

Indeed, given slow rates of recovery in the most impoverished communities (Seidman 2013), no returners mentioned having ever “fully transitioned” to living in New Orleans again. As Mariah, a mother of 2 who returned to New Orleans from Houston, summarized:

Katrina was a setback in its own way because we lost a lot of people. We lost a lot of friends and loved ones and we lost a lot of memories. A lot of things can’t be replaced. But in the overall, Katrina benefitted New Orleans a whole lot. A lot of people look at we lost a lot of New Orleans, but the waters washed away a lot and it gave a lot of people [a] new beginning. I know so many people that are in such a better position than they were pre-Katrina. It gave opportunities that a lot of people really didn’t have a chance at.

Similar to the institutional and labor market dimensions, changing social contexts in both origin and destination reveal how the return migration decision influences opportunities for mobility.

Discussion and conclusion

While essential to our understanding of some populations’ migration choices, current conceptualizations of disaster-induced migration and mobility do not fully reflect vulnerable individuals’ resettlement and recovery processes. My primary contribution in this article is to introduce the context of reception framework to the study of a vulnerable population’s post-disaster migration decisions, extending it to show how individual-level encounters with institutional, labor market, and social dimensions in origin and destination shape migration and mobility outcomes over time. A theoretical framework that links individual-level experiences to the presence of these broader contextual features is important for three reasons.

First, this approach provides a more nuanced account of the social processes underlying migration decisions. Specifically, the results show whether and how respondents make the decision to return to New Orleans is driven by their subjective comparisons of push and pull factors. Prevailing migration theories derived from neoclassical economics—which assume that a person migrates when the expected utility of living in destination is greater than the expected utility of living in origin—are predicated on individuals’ rational and objective assessments of the costs and benefits associated with the move (e.g., whether she has a job, how much money she earns, etc.). But why and how did most of the low-income, predominantly African-American mothers in my sample decide to return to New Orleans if it meant forsaking the post-disaster gains they made in neighborhood quality? The results suggest that, while rational cost-benefit calculations may exert some influence in respondents’ migration choices, insight into individuals’ subjective encounters with institutional, labor market, and social contexts in both origin and destination had much to do with the decision to return.27 Respondents such as Piper, who returned to New Orleans from Houston, did so after comparing her negative interactions with institutions such as the welfare office in destination to her more positive experiences in origin. In contrast, Tania, who moved to Houston, explicitly compared destination to origin in terms of how “ghetto” her old neighborhood and the opportunities for mobility she perceived for herself and her children. Future quantitative work can better test this idea by assessing whether objective or subjective indicators of neighborhood quality in origin and destination explain variation in individuals’ migration outcomes.28

Second, this theoretical perspective demonstrates how respondents’ perceptions of discrimination in origin and destination influence return migration decisions. Discrimination, racism, and stigmatization are social processes (Clair and Denis Forthcoming; Lamont et al. 2014) that operated throughout all contextual dimensions to influence respondents’ return migration outcomes. While past literature has documented disaster survivors’ accounts of racism and discrimination, and their relationship to mental and physical health outcomes (Chen et al. 2007; Pina et al. 2008), no work to date has linked these processes to post-disaster migration and mobility. Kimberly, for example, returned to New Orleans because she felt her evacuee status excluded her from the job market in Houston. But not all respondents who experienced labor market discrimination would return to New Orleans; much remains to be learned about why individuals respond differently to similarly hostile post-disaster contexts. For instance, Hannah conducted a 5-month job search in Houston before finally landing a position with a mobile phones retailer even after having felt discriminated against because of her evacuee status. Why do some respond to perceptions of discrimination and stigmatization by return migrating, while others exhibit greater resilience and ultimately benefit socioeconomically in the post-disaster environment? While not directly evaluated in this study, the results suggest that sensitivity to these microaggressions may underlie the return migration decision. Future work that collects and links psychological measures of interpersonal sensitivity (see, e.g., Marrow et al. 2013; Schildkraut 2011) to post-disaster migration studies would be invaluable.

Finally, the framework reveals how opportunities for migration and mobility are subject to change as institutional, labor market, and social contexts in origin and destination evolve. While cross-sectional research conducted just after Hurricane Katrina suggested that New Orleans’ poorest had permanently out-migrated (Elliott and Pais 2006; Frey and Singer 2006), these individuals are more likely to return over time (Fussell et al. 2010), though possible contextual and social network effects driving migration remained poorly understood. The results show that the social dimension factored most heavily into respondents’ return migration decisions. Although movers universally preferred the social context in New Orleans, most chose to remain in destination because they recognized it was preferable along institutional and/or labor market dimensions for themselves and their children. Over time, movers such as Grace and Nikita grew to appreciate their racially diverse neighborhoods in destination. Returners were less cognizant of these benefits while in destination, however, and responded to an initially hostile social context in destination by returning to New Orleans. While individuals’ encounters with the social dimension had much to do with migration outcomes in this study, future work that more closely scrutinizes how social ties influence a person’s selection into return migration would be invaluable. Preliminary work suggests that a complex interaction of social characteristics determines who returns to New Orleans and who does not (Asad 2014). For movers, their more salient roles as friends, mothers, and partners led to their positive selection into lower-poverty neighborhoods after Hurricane Katrina. For returners, their more salient roles as granddaughters, daughters, and “refugees” interacted to produce return migration to poorer neighborhoods in New Orleans.

Understanding how vulnerable individuals’ experiences with post-disaster institutional, labor market, and social contexts shape whether and how they decide to return migrate is essential for scholars and policymakers interested in these communities’ long-term resettlement and recovery trajectories. As we have seen, vulnerable populations rely upon a combination of positive experiences with institutional, labor market, and social contexts in origin and destination, rendering individualistic approaches to disaster recovery insufficient (Myers et al. 2008). Instead, as Eva explained, a more comprehensive approach to disaster relief encompassing these three contextual dimensions is important:

I have a good friend of mine who I would say is mostly recovered because she’s been able to establish herself here [in Dallas]. She’s been able to purchase a home, purchase transportation that is reliable, and she’s pretty much settled in. She’s got a good job and, it’s not that she didn’t have the other stressors that I have, but she’s more settled and this has become more home. For me, I think recovery would be to have more stability and to be more settled in one place. But I’m still moving. […] I think once I can purchase a home and we have some stability, I think I’ll feel more recovered.

A holistic strategy—in Eva’s case, assistance to buy a home (institutional), access to a quality job (labor market), and feeling “at home” in the post-disaster location (social)—is not only likely to facilitate survivors’ recovery in the short-term but also promote long-term mobility outcomes.

Acknowledgments

For comments on earlier versions of this article, I thank four anonymous reviewers, Monica C. Bell, Matthew Clair, Kathryn Edin, Filiz Garip, Anthony Jack, Cassandra Robertson, Patrick Sharkey, Jessica Tollette, Alba Villamil, Mary C. Waters, William Julius Wilson, Chris Winship, and Alix S. Winter, as well as participants in the Multidisciplinary Program on Inequality and Social Policy. A previous version of this paper was presented at the 2014 American Sociological Association Annual Meeting in San Francisco, where I received invaluable feedback from Alexis Merdjanoff and Lori Peek. I am indebted to Mariana Arcaya and Meghan DeNubila for research assistance. I acknowledge support from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship and the Multidisciplinary Program in Inequality and Social Policy at Harvard. The National Science Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation generously provided support for the Resilience in Survivors of Katrina Project.

Footnotes

Ethical standard The data collection procedures described above were approved by Institutional Review Boards at Harvard University and Princeton University and, as such, comply with US federal law.

Factors influencing the expected utility of living in any given area include the amount of real income an individual can expect to receive, an individual’s stock of location-specific capital, the receiving area’s amenities, locally produced public and private services, and an individual’s sense of place.

Vulnerability is determined by “the characteristics of a person or group in terms of their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist, and recover from the impact of a natural hazard” (Wisner et al. 2004: 11).

I limit my discussion here to disaster-related research in the US context. See Morrissey (2009) for an abundant literature on post-disaster migration in developing contexts.

Following the sociology of immigration literature, I use the phrase “in origin” to refer to the migrant-sending region and “in destination” to refer to the migrant-receiving region.

Zelinsky et al.’s (1971) “mobility transition” hypothesis is not reviewed here because it deals directly with migration in developing countries.

Two predominant theoretical approaches, the spatial assimilation and the place stratification models, guide urban sociologists interested in understanding why, when given the opportunity to move from high-to low-poverty neighborhoods, people often move back to disadvantaged contexts. The former emphasizes the importance of sociodemographic characteristics for residential mobility, while the latter highlights the role of institutional barriers to residential attainment net of sociodemographic controls. Neither theory is applicable here, as this literature largely addresses questions of between-neighborhood moves and not cross-metropolitan or cross-state migration. Furthermore, the uniqueness of the post-disaster context presented in this article necessitates a theoretical approach better suited for understanding migration decisions in the face of natural disasters.

Following Allard and Small (2013: 9), this includes, but is not limited to, disaster-related benefits, welfare agencies, schools, police agencies, employment centers, and the like. While some institutional support (e.g., disaster-related public assistance) is provided to evacuees regardless of their settlement location, perceptions of institutional support are localized in the sense that respondents’ differential experiences with accessing these resources in origin and destination shape how they think about a particular context’s amenability to their presence.

An alternative theory suggests that place-specific considerations of the amenities afforded by one context and unavailable in another (e.g., safety from crime, the availability of affordable housing, infrastructure, how functional public services such as schools and hospitals, etc.) may lead an individual to settle in destination after initial displacement. This approach is compatible with the theory presented here, whereby individuals make relative comparisons between origin and destination when deciding whether to settle or not. As I show, however, situating individual-level interactions within the broader institutional, labor market, and social contexts reveals that subjective experiences matter above and beyond these objective, place-specific considerations.

The International Organization for Migration defines environmental migrants as “persons or a group of persons who, for compelling reasons of sudden or progressive changes in the environment that adversely affect their lives or living conditions, are obliged to leave their habitual homes, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, and who move either within a country or abroad” (IOM 2007: 1). I use this term for the sake of clarity, but note the politicization of different labels used to categorize those displaced by natural disasters (see Morrissey 2009).