Abstract

Septal myectomy is the gold standard treatment option for patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy whose symptoms do not respond to medical therapy. This operation reliably relieves left ventricular outflow tract gradients, systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve, and associated mitral valve regurgitation. However, there remains controversy regarding the necessity of mitral valve intervention at the time of septal myectomy. While some clinicians advocate for concomitant mitral valve procedures, others strongly believe that the mitral valve should only be operated on if there is intrinsic mitral valve disease. At Mayo Clinic, we have performed septal myectomy on more than 3000 patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and in our experience, mitral valve operation is rarely necessary for patients who do not have intrinsic mitral valve disease such as leaflet prolapse or severe calcific stenosis. In this paper, we review anatomical considerations, imaging, and surgical approaches in the management of the mitral valve in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Keywords: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Mitral valve, Myectomy

Introduction

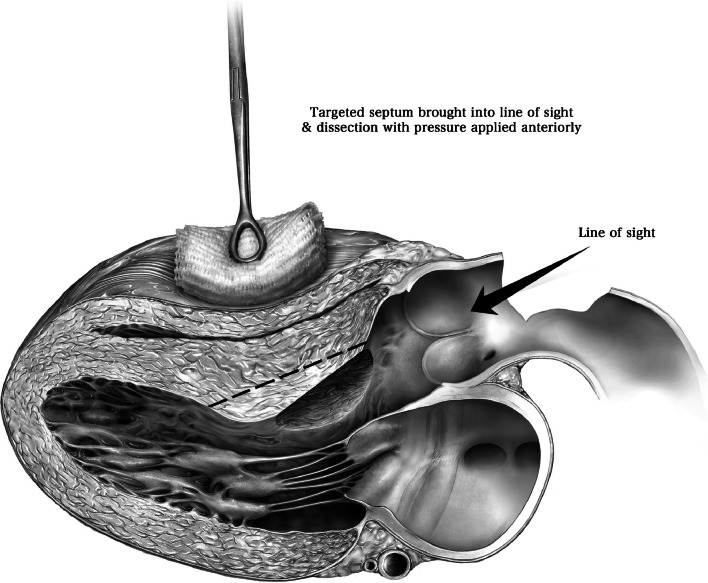

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a genetic disease that may affect as many as one in 200 people [1]. Systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve (MV) plays an important role in the pathophysiology of HCM, causing left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction and mitral valve regurgitation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Image of a posteriorly directed jet due to systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve. (Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All rights reserved)

Patients with obstructive HCM typically complain of shortness of breath on exertion, syncope, and angina-like chest pain. These symptoms may be managed with medical therapy, including beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, and disopyramide. However, for many patients with obstructive symptoms, pharmacologic treatment is often insufficient, and these patients require septal reduction therapy.

Transaortic septal myectomy is the gold standard treatment for patients with obstructive HCM whose symptoms do not respond to medical therapy. But there remains debate on whether concomitant procedures on the mitral valve are necessary to relieve mitral valve regurgitation (MR) associated with SAM. A recent review of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons database demonstrated that concomitant mitral valve operations were performed in more than a third of patients undergoing septal myectomy in the USA [2]. At Mayo Clinic, we have operated on more than 3000 patients with obstructive HCM. In our experience, concomitant mitral valve operation is performed only for patients with intrinsic mitral valve disease, or if adequate myectomy does not relieve LVOT obstruction and SAM. In a review of more than 2004 operations for obstructive HCM performed at our clinic, Hong and coauthors [3] reported that intrinsic mitral valve disease was present in 99 patients (4.9%).

The mitral valve in HCM

Papillary muscle abnormalities

Abnormalities of the mitral valve in patients with HCM may involve the papillary muscles and/or the leaflets. Papillary muscles can be hypertrophied and contribute to midventricular obstruction. At the time of midventricular septal myectomy, these hypertrophied muscles can be shaved to reduce bulk and relieve intraventricular gradients.

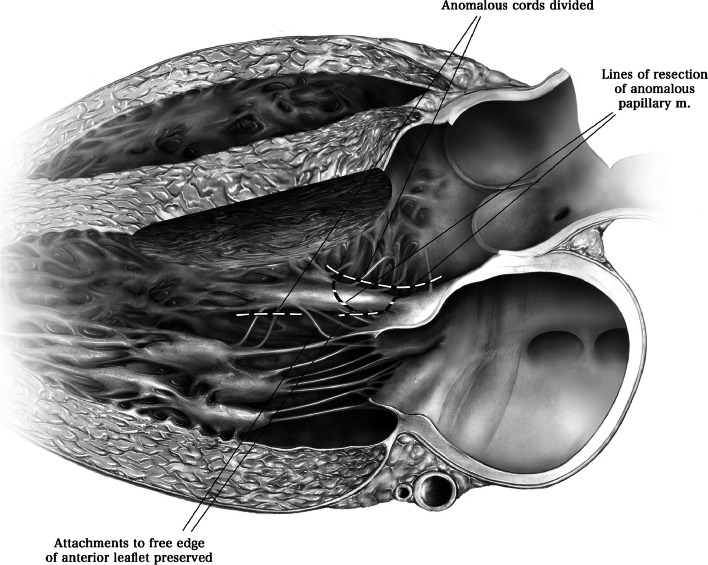

Other common papillary muscle anomalies include abnormal insertion directly into the anterior mitral valve leaflet and anterior displacement of the base of the anterolateral papillary muscle [4]. If the papillary muscle inserts into the body of the anterior leaflet, it will contribute to LVOT obstruction and should be resected at the time of septal myectomy (Fig. 2) [5]. However, papillary muscles that insert directly into the free edge of the anterior leaflet are unlikely to contribute to LVOT obstruction and can be preserved. For patients with anterior displacement of the anterolateral papillary muscle, realignment has also been proposed [6].

Fig. 2.

Transthoracic echocardiogram of a patient with an anomalous papillary muscle inserting into the anterior mitral valve leaflet (orange arrows on panel a). This anomalous papillary muscle contributed to left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (yellow arrows on panels a–c). Panel c (right side) shows the transthoracic echocardiogram of the same patient following septal myectomy and excision of the anomalous papillary muscle with preservation of chordal attachments to the leaflet edge. (Kadkhodayan A, Schaff HV, Eleid MF. Anomalous papillary muscle insertion in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17 [5]:588. Copyright The Author 2016) [5]

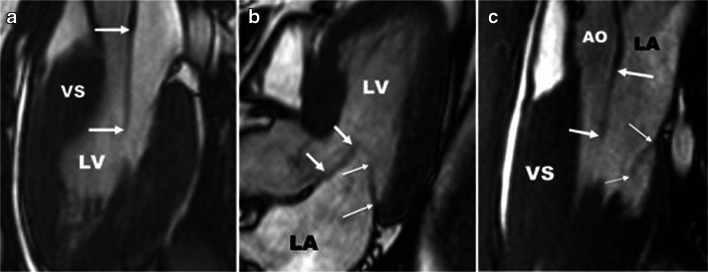

Elongation of mitral valve leaflets

There is some evidence suggesting that the mitral valve leaflets may be abnormally elongated in patients with HCM [7, 8]. Indeed, Maron and colleagues [7] demonstrated that patients with HCM appeared to have longer anterior mitral leaflet (26 ± 5 versus 19 ± 5 mm, p < 0.001) and longer posterior mitral leaflet (14 ± 4 versus 10 ± 3 mm, p < 0.001) compared with healthy control patients (Fig. 3). These authors concluded that morphological abnormalities of the mitral valve are likely a primary phenotypic expression of HCM. Further, Maron and associates suggest that elongated mitral valve leaflets are a major contributor to dynamic LVOT obstruction.

Fig. 3.

Left ventricular 3-chamber diastolic long-axis cardiac magnetic resonance images of mitral valve leaflet abnormalities in six patients with HCM. Thick arrows denote anterior mitral leaflet (AML); thin arrows, posterior mitral leaflet (PML). Panel a shows an extraordinarily long anterior mitral leaflet (AML) measuring 33 mm. Panel b demonstrates a 25 mm long anterior mitral leaflet. Panel c shows AML of 33 mm and posterior mitral leaflet length of 21 mm. AO, aorta, LA, left atrium, LV, left ventricle, VS, ventricular septum. (Used with permission of Maron MS, Olivotto I, Harrigan C, et al. Mitral valve abnormalities identified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance represent a primary phenotypic expression of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2011;124 [1]:40–47. Copyright American Heart Association, Inc.) [7]

Intrinsic mitral valve disease

Patients with obstructive HCM may also have intrinsic MV disease including prolapse with or without chordal rupture and calcification that can, in some patients, lead to valve stenosis [9, 10]. Some have argued for valve replacement in patients with obstructive HCM and intrinsic MV disease and suggest that valve repair with annuloplasty may aggravate systolic anterior motion of the mitral leaflets and decrease effectiveness of septal myectomy. In our experience, however, MV repair with annuloplasty at the time of septal myectomy is safe and effective with low risk of residual LVOT obstruction. Importantly, late follow-up of patients who need MV intervention at the time of myectomy reveals better survival of those who had valve repair compared with those who had mitral valve replacement.

Echocardiography

All patients with HCM should undergo transthoracic echocardiography prior to septal reduction therapy. Preoperative echocardiography is necessary to measure LVOT gradient, SAM, and to quantify mitral valve regurgitation, as well as determine whether intrinsic mitral valve disease is present. The direction of the jet of mitral regurgitation on Doppler echocardiography has been used to identify SAM-related valve leakage (Fig. 1) [11–13]. If the MR jet is posteriorly directed, there is a high likelihood that mitral valve leakage is SAM-related, but a central jet or even an anteriorly directed Doppler jet does not exclude systolic anterior motion as the underlying cause of MR. [13] If there is doubt about the nature of mitral valve regurgitation, we recommend careful intraoperative evaluation of the mitral valve using transesophageal echocardiography, and if no prolapse is identified, we proceed with septal myectomy to relieve SAM and then reassess MV function postbypass. Preoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is unnecessary in most patients, but TEE is critically important intraoperatively in assessing the results of myectomy postbypass.

Surgical approaches

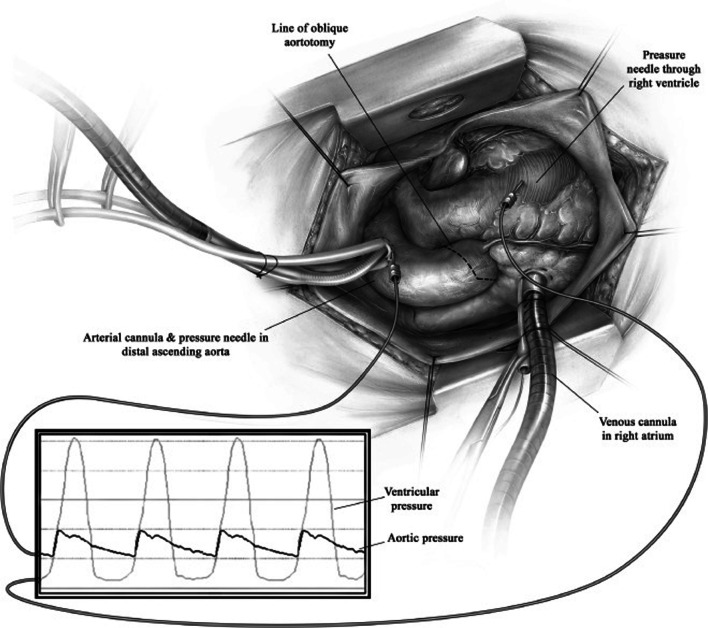

Transaortic septal myectomy

Surgical treatment of obstructive HCM has evolved since Morrow’s classical myectomy [14], and the current gold standard septal reduction therapy is extended septal myectomy [15]. However, there is still debate regarding surgical management of the mitral valve, and some clinicians advocate routine concomitant mitral valve surgery for patients undergoing septal myectomy [6]. Many clinicians, however, favor septal myectomy without operation on the mitral valve, and this is the approach we prefer at Mayo Clinic. In our experience, isolated septal myectomy adequately relieves LVOT obstruction, SAM, and associated mitral valve regurgitation [3]. In general, isolated myectomy for obstructive HCM is sufficient under two conditions. First, the mitral valve regurgitation is related to SAM with no intrinsic mitral valve abnormalities, and secondly that a proper extended myectomy is performed, the key to which is excision of muscle towards the apex beyond the contact site. When these conditions are met, concomitant mitral valve surgery is almost never required.

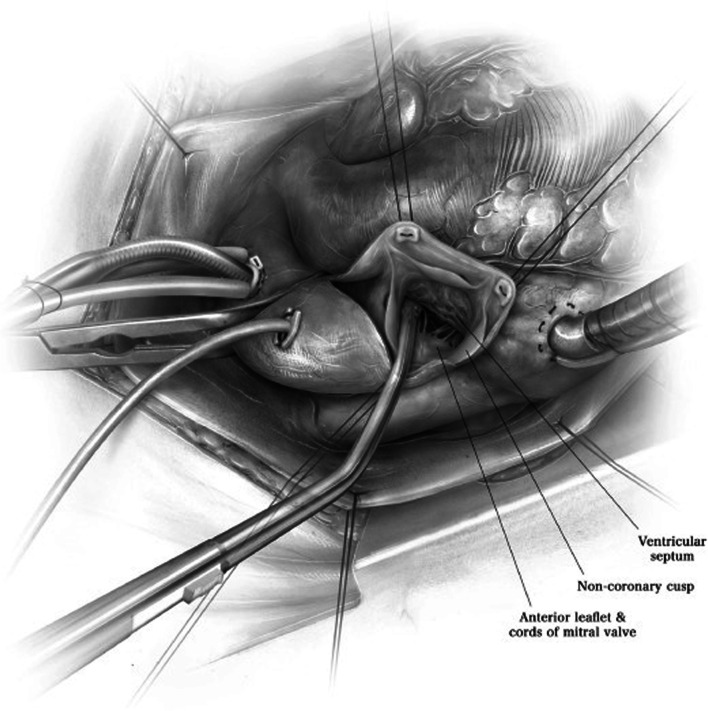

We have previously described our surgical technique of septal myectomy in detail [16]. In brief, following a median sternotomy, we measure gradients between the aorta and left ventricle directly using needle manometry (Fig. 4). The heart is arrested with cold blood cardioplegia. An oblique aortotomy is made, which extends into the noncoronary sinus 1 cm above the aortic annulus. Adequate exposure and visualization of the subaortic septum can be facilitated by a few maneuvers (Fig. 5). First, right-sided pericardial stitches are used to elevate the right side of the heart. Second, stay sutures can be used to retract the inferior edges of the aorta. Third, we place a cardiotomy sucker through the aortic valve to retract the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve posteriorly. Fourth, tilting the operating table towards the left facilitates optimal alignment of the surgeon’s view.

Fig. 4.

After standard midline sternotomy, the pressure between the aorta and the left ventricle is measured directly using needle manometry. (Used with permission of Nguyen A, Schaff HV. Transaortic septal myectomy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;22 [4]:200–215. Copyright Elsevier Inc.) [16]

Fig. 5.

Adequate exposure is achieved by four maneuvers. First, right-sided pericardial stitches are used to elevate the right side of the heart. Second, stay sutures can be used to retract the inferior edges of the aorta. Third, a cardiotomy sucker is placed through the aortic valve to retract the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve posteriorly. Fourth, tilting the operating table towards the left facilitates optimal alignment of the surgeon’s view. (Used with permission of Nguyen A, Schaff HV. Transaortic septal myectomy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;22 [4]:200–215. Copyright Elsevier Inc.) [16]

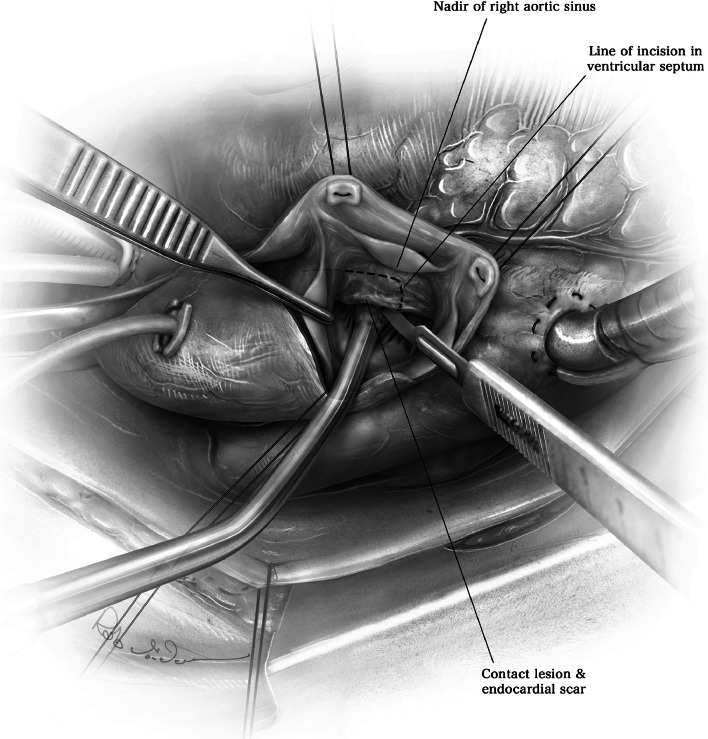

The white endocardial scar, which demarcates the contact lesion produced by apposition of the anterior mitral valve leaflet on the basal septum, can be seen in most patients (Fig. 6). This contact lesion should serve as a guide to the length of the myectomy, which must extend beyond the scarring. A No. 10 knife blade on a long handle is used to begin the myectomy with an upward incision in the septum, approximately 3–4 mm to the right of the nadir of the right aortic sinus (Fig. 6). The depth of the incision is approximately 8 mm, and the width of the No. 10 knife blade can serve as a guide for this. The incision is then carried upwards and then counter-clockwise (Fig. 7). Adequate extension of the myectomy towards the apex is critical, as failure to extend the incision distally can cause recurrent gradients and symptoms.

Fig. 6.

The white endocardial scar demarcates the contact lesion between the anterior mitral valve leaflet and the septum, and is used to guide the initial incision of the septum. (Used with permission of Nguyen A, Schaff HV. Transaortic septal myectomy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;22 [4]:200–215. Copyright Elsevier Inc.) [16]

Fig. 7.

Adequate myectomy is performed by extending the initial incision towards the apex of the left ventricle. Failure to perform an adequate myectomy can result in inadequate relief of LVOT gradients. (Used with permission of Nguyen A, Schaff HV. Transaortic septal myectomy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;22 [4]:200–215. Copyright Elsevier Inc.) [16]

The aortotomy is closed in two layers with 4–0 polypropylene suture. Adequacy of myectomy is assessed in the operating room by direct needle manometry and transesophageal echocardiography. It is important to emphasize how crucial it is to perform an extended myectomy [17]. In our experience, the most common cause of reoperation after myectomy is inadequate length of initial septal excision, rather than inadequate depth of septal excision [18]. In general, we perform an extended septal myectomy and assess results immediately in the operating room using transesophageal echocardiography and direct needle manometry. If residual SAM, mitral valve regurgitation, or LVOT gradients (> 15–20 mmHg) are detected, additional myectomy is performed with a second cardiopulmonary bypass run. If there is no pressure gradient or SAM but there is significant regurgitation of the mitral valve, surgery on the mitral valve may be considered during the second bypass run [3].

Concomitant procedures on the papillary muscles and/or mitral valve

Abnormal papillary muscles that insert into the body of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve may contribute to obstruction and should be excised (Figs. 2 and 8). However, anomalous papillary muscles that insert into the free edge of the anterior leaflet are unlikely to contribute to LVOT obstruction and should be preserved. Chordal attachments to the free edge of the anterior mitral valve leaflet should also be preserved [5].

Fig. 8.

Abnormal papillary muscles may insert into the body of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve. These papillary muscles should be resected, as they can crowd the left ventricular outflow tract and contribute to symptoms of obstruction. (Used with permission of Nguyen A, Schaff HV. Transaortic septal myectomy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;22 [4]:200–215. Copyright Elsevier Inc.) [16]

As discussed above, patients with obstructive HCM may have intrinsic mitral valve abnormalities, such as leaflet prolapse, chordal rupture, and even mitral valve stenosis [10]. In these cases, direct mitral valve surgery is required in addition to extended myectomy. We recommend concomitant mitral valve repair rather than replacement, as long-term results are better following repair. Indeed, in a review of 2004 operations for obstructive HCM performed at our Clinic, 174 patients required mitral valve surgery. Mitral valve repair was successful in 133 of these patients (76%), and repair techniques depend on the specific etiology of intrinsic mitral valve disease [10]. In a previous publication, we have detailed methods of valve repair in patients undergoing septal myectomy [9].

Some groups perform adjunctive procedures to prevent SAM and LVOT obstruction after myectomy. These maneuvers include anterior leaflet plication [19, 20], anterior mitral leaflet extension [21–23], and retention plasty [24, 25]. We have not found these techniques necessary if an adequate extended myectomy is performed.

Combined myectomy and anterior mitral leaflet plication was initially proposed by Cooley, and McIntosh et al. [19, 20] stated that plication should be used as an alternative to mitral valve replacement. The plication is performed after identifying that the mitral valve has an increased area and length. This procedure involves longitudinal plication of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve with multiple interrupted 4–0 Prolene mattress sutures. Horizontal plication of the anterior mitral valve leaflet has also been proposed [26].

In contrast, Kofflard et al. and van der Lee et al. [21, 23] have proposed anterior mitral leaflet extension as a means to reduce SAM. This is intended to be performed in situations where the surgeon determines that myectomy alone would yield a suboptimal result. Using this technique, the anterior leaflet is incised longitudinally from its subaortic hinge point to the rough zone. An autologous pericardial patch, cut in an oval shape approximately 3 cm wide and 2.5 cm long, is sewn onto the anterior leaflet at the site of the incision. These authors speculate that the patch may serve to stiffen the leaflet, making it less likely to buckle in the presence of Venturi or flow drag forces [21]. In a study of 29 patients who underwent combined anterior mitral leaflet extension with myectomy, clinical results were satisfactory with improvement in functional status, reduction of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, and attenuation of MR and SAM of the mitral valve at 3.4-year follow-up [23].

Combined mitral valve leaflet retention plasty is another technique that has been proposed, especially for pediatric patients with obstructive HCM. With this technique, both commissures of the mitral valve are closed by pledgeted Prolene mattress sutures. Limiting the mobility of the anterior mitral valve leaflet reduces SAM, and favorable results have been reported [24]. Although this method has also been used in adults, late follow-up is limited [25].

Early mortality following septal myectomy

Myectomy has been performed for more than 50 years with proven efficacy and safety in experienced centers. Indeed, operative mortality is reported to be less than 1% at high-volume centers with dedicated HCM teams [27, 28]. When performed by experienced surgeons, septal myectomy reliably relieves LVOT gradients, SAM, and mitral valve regurgitation associated with HCM. However, it is also important to acknowledge that myectomy may be an unfamiliar operation for many cardiac surgeons, and myectomy performed in low-volume centers by surgeons with limited experience appears to have suboptimal outcomes [29]. Indeed, Maron and colleagues [30] argue that surgical treatment of HCM should be performed at dedicated centers in order to achieve the best patient outcomes.

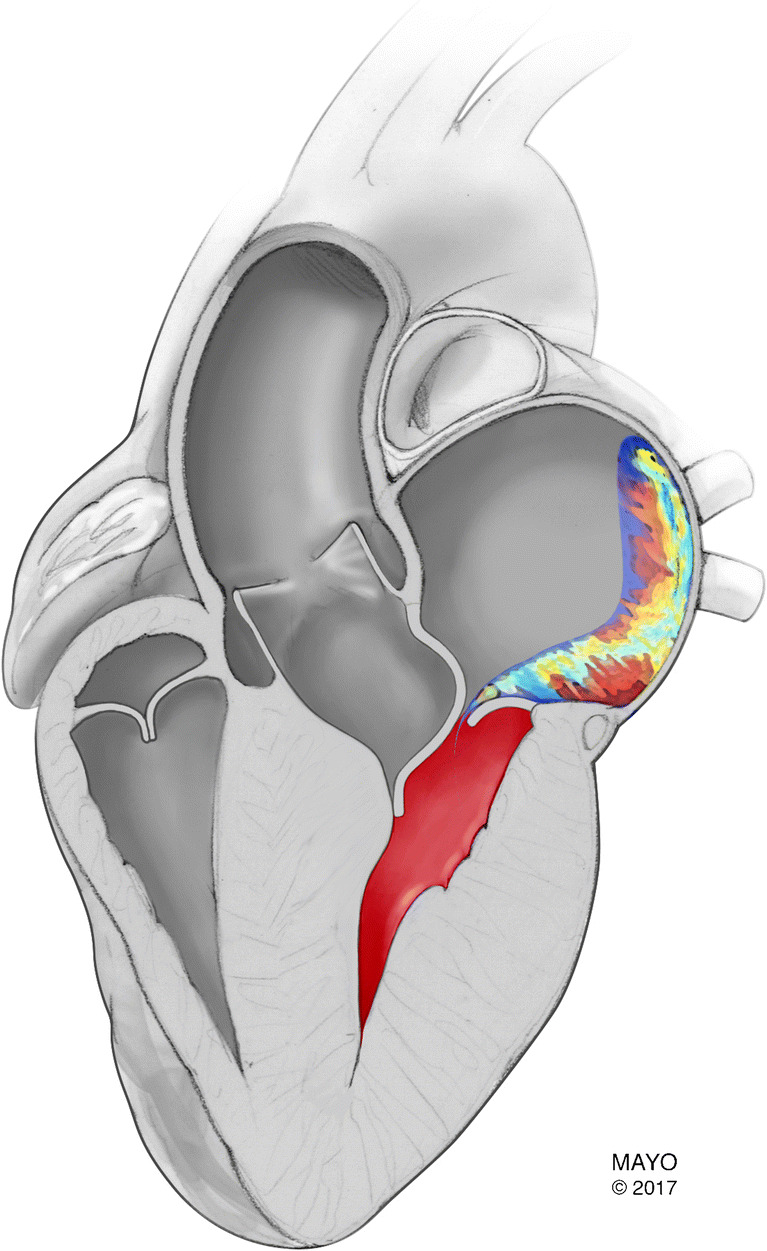

Mitral valve regurgitation in obstructive HCM—surgical outcomes

Although there is some debate regarding need for concomitant mitral valve procedures to relieve mitral valve regurgitation associated with SAM, recent studies have shown increased perioperative risks for patients who undergo concomitant procedures [2, 31, 32]. For example, among patients reported to the STS database, operative mortality was 2.8% for myectomy combined with a mitral valve procedure compared with 1.6% for septal myectomy alone (p = 0.046). For patients with SAM-mediated MR, we prefer isolated septal myectomy over the aforementioned combined procedures of myectomy and concomitant mitral valve repair or replacement. In a review of almost 1500 patients who underwent septal myectomy for obstructive HCM at Mayo Clinic (92% isolated myectomy, and 8% myectomy with mitral valve operation for intrinsic MV disease or residual gradients), Nguyen and coauthors [33] demonstrated that greater than moderate MR was present in only 1% following septal myectomy.

In another review of almost 2000 patients who underwent septal myectomy at Mayo Clinic, Hong and colleagues reported that approximately 9% of patients required concomitant mitral valve surgery. Most of these patients had intrinsic mitral valve disease. If an operation on the mitral valve was performed, repair of the native valve was successful in 86.7% of patients, and only 13.3% required mitral valve replacement. Importantly, for patients who required intervention on the mitral valve, late survival was superior for those who had repair of the mitral valve instead of replacement (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Late survival of patients with obstructive HCM who underwent septal myectomy and concomitant mitral valve intervention at Mayo Clinic. Patients who underwent mitral valve repair had significantly better late survival compared with patients who underwent mitral valve replacement. (Used with permission of Hong JH, Schaff HV, Nishimura RA, et al. Mitral regurgitation in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: implications for concomitant valve procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68 [14]:1497–1504. Copyright The American College of Cardiology Foundation) [3]

Conclusion

Septal myectomy for obstructive HCM is the gold standard treatment option to relieve LVOT gradients, mitral valve regurgitation, and systolic anterior motion. Although some clinicians advocate concomitant surgery on the mitral valve to address SAM and associated regurgitation of the mitral valve, these procedures are rarely needed in our practice. Adequate myectomy addresses the underlying pathophysiology in most patients. Concomitant surgery on the mitral valve should be performed in patients with intrinsic mitral valve disease, and in those patients, mitral valve repair is preferred because of better late survival compared with patients who undergo concomitant mitral valve replacement.

Sources of funding

This work was supported by the Paul and Ruby Tsai Family.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical statement

NA

Informed consent

NA

Human and Animal rights

NA

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1249–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei LM, Thibault DP, Rankin JS, et al. Contemporary Surgical Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in the United States. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107:460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong JH, Schaff HV, Nishimura RA, et al. Mitral Regurgitation in Patients With Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy: Implications for Concomitant Valve Procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1497–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.07.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherrid MV, Balaram S, Kim B, Axel L, Swistel DG. The Mitral Valve in Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Test in Context. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1846–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadkhodayan A, Schaff HV, Eleid MF. Anomalous papillary muscle insertion in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17:588. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jew007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song HK, Turner J, Macfie R, et al. Routine Papillary Muscle Realignment and Septal Myectomy for Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106:670–675. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maron MS, Olivotto I, Harrigan C, et al. Mitral valve abnormalities identified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance represent a primary phenotypic expression of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2011;124:40–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.985812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groarke JD, Galazka PZ, Cirino AL, et al. Intrinsic mitral valve alterations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy sarcomere mutation carriers. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19:1109–1116. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan CK, Dearani JA, Sundt TM, 3rd, Ommen SR, Schaff HV. What is the best surgical treatment for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and degenerative mitral regurgitation? Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:727–731. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong J, Schaff HV, Ommen SR, Abel MD, Dearani JA, Nishimura RA. Mitral stenosis and hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: An unusual combination. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1044–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoit BD, Penonen E, Dalton N, Sahn DJ. Doppler color flow mapping studies of jet formation and spatial orientation in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 1989;117:1119–1126. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(89)90871-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeo TC, Miller FA, Jr, Oh JK, Schaff HV, Weissler AM, Seward JB. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with obstruction: important diagnostic clue provided by the direction of the mitral regurgitation jet. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1998;11:61–65. doi: 10.1016/S0894-7317(98)70121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hang Dustin, Schaff Hartzell V., Nishimura Rick A., Lahr Brian D., Abel Martin D., Dearani Joseph A., Ommen Steve R. Accuracy of Jet Direction on Doppler Echocardiography in Identifying the Etiology of Mitral Regurgitation in Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2019;32(3):333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2018.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrow AG, Reitz BA, Epstein SE, et al. Operative treatment in hypertrophic subaortic stenosis. Techniques, and the results of pre and postoperative assessments in 83 patients. Circulation. 1975;52:88–102. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.52.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaff HV, Said SM. Transaortic Extended Septal Myectomy for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;17:238–250. doi: 10.1053/j.optechstcvs.2012.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen A, Schaff HV. Transaortic Septal Myectomy for Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;22:200–215. doi: 10.1053/j.optechstcvs.2018.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Messmer BJ. Extended myectomy for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:575–577. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)92268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho YH, Quintana E, Schaff HV, et al. Residual and recurrent gradients after septal myectomy for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-mechanisms of obstruction and outcomes of reoperation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:909–915. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooley DA. Surgical techniques for hypertrophic left ventricular obstructive myopathy including mitral valve plication. J Card Surg. 1991;6:29–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.1991.tb00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McIntosh CL, Maron BJ, Cannon RO, 3rd, Klues HG. Initial results of combined anterior mitral leaflet plication and ventricular septal myotomy-myectomy for relief of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1992;86:II60–II67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kofflard MJ, van Herwerden LA, Waldstein DJ, et al. Initial results of combined anterior mitral leaflet extension and myectomy in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:197–202. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwammenthal E, Levine RA. Dynamic subaortic obstruction: a disease of the mitral valve suitable for surgical repair? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:203–206. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Lee C, Kofflard MJ, van Herwerden LA, Vletter WB, ten Cate FJ. Sustained improvement after combined anterior mitral leaflet extension and myectomy in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2003;108:2088–2092. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103625.15944.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delmo Walter EM, Siniawski H, Hetzer R. Sustained improvement after combined anterior mitral valve leaflet retention plasty and septal myectomy in preventing systolic anterior motion in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy in children. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;36:546–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasseri BA, Stamm C, Siniawski H, et al. Combined anterior mitral valve leaflet retention plasty and septal myectomy in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:1515–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balaram SK, Sherrid MV, Derose JJ, Jr, Hillel Z, Winson G, Swistel DG. Beyond extended myectomy for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the resection-plication-release (RPR) repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maron BJ. Controversies in cardiovascular medicine. Surgical myectomy remains the primary treatment option for severely symptomatic patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2007;116:196–206. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.691378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maron BJ, Dearani JA, Ommen SR, et al. Low Operative Mortality Achieved With Surgical Septal Myectomy: Role of Dedicated Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Centers in the Management of Dynamic Subaortic Obstruction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1307–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim LK, Swaminathan RV, Looser P, et al. Hospital Volume Outcomes After Septal Myectomy and Alcohol Septal Ablation for Treatment of Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: US Nationwide Inpatient Database, 2003-2011. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:324–332. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maron BJ, Dearani JA, Maron MS, et al. Why we need more septal myectomy surgeons: An emerging recognition. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:1681–1685. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Afanasyev A, Bogachev-Prokophiev A, Lenko E, et al. Myectomy with mitral valve repair versus replacement in adult patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2019;28:465–472. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivy269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holst KA, Hanson KT, Ommen SR, Nishimura RA, Habermann EB, Schaff HV. Septal Myectomy in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: National Outcomes of Concomitant Mitral Surgery. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen A, Schaff HV, Nishimura RA, et al. Does septal thickness influence outcome of myectomy for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;53:582–589. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]