Abstract

Objectives

To determine any change in referral patterns and outcomes in children (0–18) referred for child protection medical examination (CPME) during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with previous years.

Design

Retrospective observational study, analysing routinely collected clinical data from CPME reports in a rapid response to the pandemic lockdown.

Setting

Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Trust, which provides all routine CPME for Birmingham, England, population 1.1 million including 288 000 children.

Participants

Children aged under 18 years attending CPME during an 18-week period from late February to late June during the years 2018–2020.

Main outcome measures

Numbers of referrals, source of disclosure and outcomes from CPME.

Results

There were 78 CPME referrals in 2018, 75 in 2019 and 47 in 2020, this was a 39.7% (95% CI 12.4% to 59.0%) reduction in referrals from 2018 to 2020, and a 37.3% (95% CI 8.6% to 57.4%) reduction from 2019 to 2020. There were fewer CPME referrals initiated by school staff in 2020, 12 (26%) compared with 36 (47%) and 38 (52%) in 2018 and 2019, respectively. In all years 75.9% of children were known to social care prior to CPME, and 94% of CPME concluded that there were significant safeguarding concerns.

Conclusions

School closure due to COVID-19 may have harmed children as child abuse has remained hidden. There needs to be either mandatory attendance at schools in future or viable alternatives found. There may be a significant increase in safeguarding referrals when schools fully reopen as children disclose the abuse they have experienced at home.

Keywords: child protection, community child health, non-accidental injury

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a highly robust study: we obtained child protection medical examination (CPME) reports for 97% of CPME referrals during the study period.

We ensured consistency of data extraction by double reviewing every report, with further consensus discussions for the few cases that raised uncertainties.

The team extracting the data comprised highly experienced paediatricians with expertise in child abuse.

One weakness is that we only considered minor injuries from outpatient CPME, excluding those admitted to hospital, so our findings do not include those with more serious, non-accidental injury. However, they would be taken to hospital for treatment due to the severity of their injuries.

Introduction

Nearly 400 000 children in England each year are defined as ‘children in need’; these are children who require additional services, including child protection, to maintain a satisfactory level of health or development.1 Since the lockdown began, there are burgeoning concerns that child protection referrals have decreased, with professionals reporting limited opportunities to make accurate assessments of children’s needs.2 Legislation sets out the specific roles and responsibilities of agencies for undertaking child protection enquiries when a child or young person is referred for suspected maltreatment,3 including formal child protection medical examinations (CPME). The purpose of CPME is to provide a holistic assessment of the child’s health, document any injuries and determine possible causes including the reasonable likelihood of injuries being inflicted or non-inflicted. A report is provided to inform any child protection investigations. CPMEs are performed or supervised by an experienced consultant paediatrician,4 adhering to rigorous standards in respect of consent; conduct of the examination; documentation of history; findings and formulation; photo-documentation and report writing,5 with reports subject to regular peer review.6

Birmingham is the second largest city in the UK, with a diverse population and is the largest local authority in Europe. It is also a relatively young city, with 23% of its population being children under the age of 16 years.7 The proportion of children subject to a child protection plan is higher than for the UK as a whole8 and 35% of children live in poverty.8 In Birmingham, CPMEs are generally undertaken within a community setting during working hours, often for children who have disclosed maltreatment to school or nursery staff, who then refer them to Birmingham Children’s Trust (social care). Children with suspected sexual abuse are assessed separately, within specialised, regional child sexual assault referral centres. Hospital-based paediatricians perform CPMEs for those children with more significant injuries requiring treatment and for out-of-hours referrals. During the COVID-19 lockdown the community based CPME service provided extended hours (6 April to 23 May 2020) that covered evenings and weekends to minimise hospital attendance so an increase in referrals for CPME was expected.

Schools are at the frontline of child safeguarding; educational staff are often the first to report potential child abuse. This raises concerns that vulnerable children are now invisible to professionals and potentially ‘at risk’ in homes where families face even greater hardships.8 Such ‘collateral damage’9 has been borne out by evidence that only 10% of children on a child protection plan or ‘in-need’ were attending schools that were remaining open specifically for their benefit and even where schools are open for selected year groups, attendance remains very low.10

Although there has been much professional concern about the potential risk children have faced at home there have been limited data, with one report of an increase in abusive head trauma noted in London11 and a short report from the Northeast of England noting a dramatic decrease in CPME referrals.12 This current study was designed as a rapid response to fill gaps in knowledge about child protection referrals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The aim was to determine differences in the number and outcomes of child protection referrals for CPME in Birmingham during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown (March to June 2020) compared with the same periods in 2018 and 2019. Our research questions were:

What is the difference in child protection referrals during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with previous years?

Are there differences in demographic details, referral source and outcomes for children presenting for CPME during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with previous years?

Methods

Study design

Retrospective observational study of referrals for CPME. It adhered to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidance.13

Setting and sample

All children aged 0–18 attending for CPME at Birmingham Community Healthcare Trust (BCHT), England. BCHT provides specialist CPME for the population of Birmingham, total population 1.1 million of which 288 000 are children aged <18.7 Data were collected for all CPME for 18-week periods in 2018, 2019 and 2020, from the last week in February, when schools returned following the half-term holiday, to the end of June and noting the variation mid-2020 when extended hours were running.

Procedure

We obtained a list of all children referred for CPME from the booking service, which is the single point of contact for all CPME referrals in BCHT, and accessed the electronic patient records (EPR) for these children, obtaining copies of reports from CPME. We read the reports, and completed an anonymised data extraction form for each CPME (online supplemental table 1). The data collection form was in three parts: (1) child demographic data, including age, gender, school age group (preschool, primary, secondary, post-16), in a special school or not, (2) referral details including whether an index case or referred as a sibling group, source of initial disclosure, who the allegation was against, whether the child had previous referral to social care and if so, the current social care status, and whether the child had ever been on a child protection plan and (3) outcomes of the CPME including whether there were physical findings to support non-accidental injury (NAI) or neglect, and, if so, what were the physical findings; likelihood of NAI; whether NAIs were present on more than one body part; were their injuries consistent with previous NAI; whether the report indicated significant safeguarding concerns; if the concerns were related to factors other than NAI; and, if so, what?

bmjopen-2020-042867supp001.pdf (100.7KB, pdf)

Outcomes were taken either directly from the conclusion of the CPME report, or if the conclusion was unclear, were determined based on the description of injuries and events within the report. If the CPME was not available, we used the EPR for demographics, referral source and safeguarding history, omitting data on outcomes of CPME.

Prior to commencing data extraction, all the clinicians reviewed 10 anonymised CPME reports which were then reviewed and discussed by the whole group. This enabled any differences in interpretation of CPME to be resolved and ensured quality and consistency of data extraction.

Clinicians worked in pairs, consisting of a specialist consultant in child protection (either named or designated doctors for safeguarding) and a specialist trainee in paediatrics, all of whom have a minimum of 4 years postgraduate medical training in child health. Each case had data extracted independently by the consultant and trainee, to ensure consistency. In the event of disagreement the case was reviewed by another consultant.

Study size

All assessments were included. The time period included the last week in February which was before there was significant concern in schools about COVID-19. Data collection continued for the month of June to enable any change in referral CPME patterns with the partial reopening of some primary schools.

Statistical analysis

Anonymised data were entered into SPSS version 25. Cases were analysed by the year of referral. If children had more than one CPME during the study period, each CPME was considered as a separate case. Referral rates between years for the whole 18-week period were compared using incidence rate ratios (IRR). IRRs for 2 weekly time periods comparing 2018/2019 with 2020 were also calculated and plotted on a graph with 95% CIs. To compare differences in variables between the years, Kruskal-Wallis tests were run for continuous variables (age, number of types of injuries) and χ2 tests were run for categorical variables.

Patient and public involvement

As a rapid observational study using retrospective records, we were unable to include children who had been through a CPME or their parents in the study. However we have a Children and Young People’s Advisory Group whom we intend to involve in the dissemination and guidelines for practitioners.

Results

There were 200 CPMEs during the study period; 193 had CPME reports available with complete information from 191.

Referral numbers

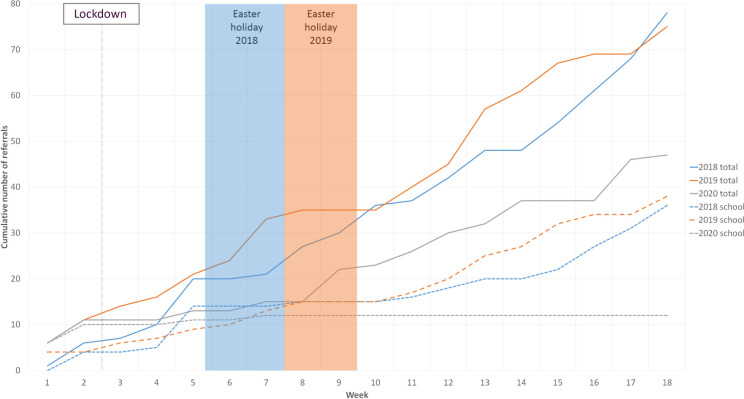

There were fewer CPME referrals in 2020 compared with previous years, as shown in figure 1, with 78 in 2018, 75 in 2019 and 47 in 2020. There was a 39.7% (95% CI 12.4% to 59.0%) reduction in referrals from 2018 to 2020, and a 37.3% (95% CI 8.6% to 57.4%) reduction from 2019 to 2020. The IRR for 2020 compared with 2018/2019 was 0.61 (95% CI 0.43% to 0.86%) showing an overall reduction of 39% (95% CI 14% to 57%).

Figure 1.

Cumulative weekly CPME referrals by year for all referrals and school referrals. CPME, child protection medical examination.

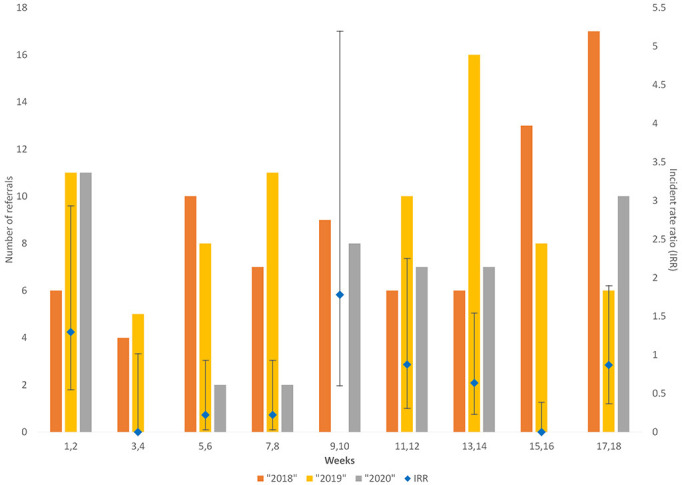

The 2 weekly data show that there was a significant drop in referrals for a 6-week period from weeks 3/4 to weeks 7/8, see figure 2. There was some evidence of an increase in referrals during weeks 9/10 in 2020 after which referral rates were broadly similar, with all CIs crossing 1, apart from weeks 15/16 when there were no referrals in 2020.

Figure 2.

Totals of weekly referrals by year and IRR comparing combined incidence for 2018/2019 against 2020 incidence. IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Secondary outcomes

A summary of referrals, demographics, social care history and outcomes of CPME is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of key findings

| Variables, N | All 200 |

2018 78 |

2019 75 |

2020 47 |

P value |

| Age in months Median (IQR) | 69 (85) | 72.5 (76) | 70 (109) | 55 (77) | 0.598 |

| Gender Female (%) | 73 (36.5) | 32 (41.0) | 31 (41.3) | 10 (21.3) | 0.046 |

| School status (%) | |||||

| Preschool | 85 (42.5) | 34 (43.6) | 30 (40.0) | 21 (44.7) | 0.637 |

| Primary (reception—year 2006) | 78 (39.0) | 32 (41.0) | 26 (34.7) | 20 (42.6) | |

| Secondary (year 2007–2011) | 32 (16.0) | 11 (14.1) | 16 (21.3) | 5 (10.6) | |

| College/sixth form (year 2012–2013) | 5 (2.5) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (4.0) | 1 (2.1) | |

| Is child an index case (vs sibling or household contact)? Yes (%) | 134 (67) | 46 (59.0) | 56 (74.7) | 32 (68.1) | 0.117 |

| Source of referral (who did child disclose abuse to, or who initiated CPME referral) (%) | |||||

| School or yearly years staff | 86 (43.9) | 36 (47.4) | 38 (52.1) | 12 (25.5) | 0.015 |

| Social care staff | 22 (11.2) | 10 (13.2) | 3 (4.1) | 9 (19.1) | |

| Police | 22 (11.2) | 11 (14.5) | 7 (9.6) | 4 (8.5) | |

| Family member | 36 (18.4) | 9 (11.8) | 17 (23.3) | 10 (21.3) | |

| Medical professional | 4 (2.0) | 2 (2.6) | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Foster carer | 7 (3.6) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.7) | 4 (8.5) | |

| Sibling current inpatient due to NAI | 12 (6.1) | 6 (7.9) | 1 (1.4) | 5 (10.6) | |

| Other | 7 (3.6) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (4.1) | 3 (6.4) | |

| Was child known to social care prior to CPME referral? Yes (%) | 151 (75.9) | 58 (74.4) | 56 (75.7) | 37 (78.7) | 0.857 |

| Is child an open case to social care now? Yes (%) | 106 (53.3) | 39 (50.0) | 38 (51.4) | 29 (61.7) | 0.409 |

| Are there physical findings to support NAI or neglect? Yes (%) | 98 (51.0) | 32 (41.0) | 46 (59.0) | 27 (57.4) | 0.071 |

| Does the report indicate significant safeguarding concerns? Yes % | 180 (93.8) | 69 (88.5) | 64 (95.5) | 47 (100) | 0.014 |

CPME, child protection medical examination; NAI, non-accidental injury.

There were significantly fewer referrals made by school or early years staff in 2020 compared with other years, with only two school referrals received after lockdown. There was no increase in referrals or disclosures from other sources. In each year, several referrals were initiated when children disclosed abuse to grandparents and non-resident parents or by relatives who witnessed abuse.

There were significantly fewer girls referred in 2020. In total across all years, 67% of children were index cases who disclosed potential abuse, or had concerning injuries noted by others leading to referral; the remaining 33% were siblings of these index cases. Across all years 75.9% of children were known to social care at any time prior to CPME, 53% were open cases in receipt of support from social care immediately prior to CPME and 39% were currently or had previously been subject to a child protection plan (where maltreatment has been substantiated).

The findings in 51% of all CPME were that there was evidence of NAI or neglect, with 55% of these children having injuries, typically bruising, on more than one area of their body implying more significant NAI. In 90% of all CPME, it was concluded that there were significant safeguarding concerns: even if there was not evidence to substantiate NAI, there were significantly fewer children in this category in 2018, but the reasons for this are unclear. There was no other statistical evidence of differences in demographics, social care histories, referral sources and outcomes; further details are shown in online supplemental table 2.

bmjopen-2020-042867supp002.pdf (157.4KB, pdf)

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

This study found a significant drop of 39% (95% CI 14% to 57%) in CPME referrals during 2020 compared with previous years with 78 referrals in 2018, 75 in 2019 and 47 in 2020. This drop coincides with the near total absence of referrals made by schools after school closure in March, with no recovery in school referrals after schools partially reopened in June. Referrals from other sources did not increase in 2020, showing that other agencies did not fully compensate for school closure. The children referred for CPME in 2020 had similar social care histories to other years with the majority being previously known to social care and approximately half being open cases at the time of referral. In all years, the vast majority of CPME reports concluded that there were significant safeguarding concerns relating to physical abuse, domestic violence, emotional abuse or neglect.

Our trust is the largest provider of community paediatric services in England, managing all requests for outpatient CPME for Birmingham residents. The extended hours offered during lockdown meant that we could include children with minor injuries needing CPME who ordinarily would be managed by acute hospital trusts, so our findings may actually be an underestimation of the decreased referral rate. Our findings should be generalisable outside of Birmingham, as this is a large multicultural city with above average levels of social deprivation and is the largest Local Authority in Europe.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies, discussing important differences in results

Although the drop in CPME referrals has been noted elsewhere in the UK,12 the longer duration of our study enabled us to examine any effects of the partial reopening of schools. Our detailed analysis of referral details and outcomes identified the change in referral patterns this year, which is a novel finding. As our CPME service covers a fixed population, we can expect that changes in referral patterns are genuine, unlike tertiary paediatric centres whose referrals are determined by clinical need not home address.11

Meaning of the study: possible explanations and implications for clinicians and policymakers

Our findings further evidence the hidden harm to children from COVID-19. The significant decrease in CPME referrals is likely largely a result of school closure and the partial reopening of schools has not altered this trend. Attending school provides children and young people with access to a trusted adult and a safe space outside of the family home. Removing this provision increases the potential risk of abuse going unseen. Many schools have made strenuous efforts to maintain contact through remote methods, but these are not always private and it is not known who else may be in the room.

Although UK government guidance was for vulnerable children, identified as those with an allocated social worker, to continue attending school, less than 10% did so.10 Nearly half of those referred for CPME were not in this category so had no protection. Disclosures to school staff by older children also protects younger siblings from abuse and neglect. It is concerning that 39% of children referred for CPME were either currently or previously subject to CPP, this suggests even if there is a lower threshold for subsequent referral that CPPs are not providing adequate safeguards for vulnerable children. Missed sentinel NAI such as bruising, may lead to children subsequently presenting with serious injuries.14 15 These sentinel NAI are typical of community CPME referrals and the drop in referral rate therefore represents a much greater risk of harm. While UK government policy is for mandatory school attendance to begin in September 2020, it is unclear at the timing of writing how this will be implemented. It is vital that this is encouraged and enforced by schools given that currently less than 40% of eligible primary school pupils are attending.10 Low attendance rates may enable abusing parents to keep their children at home with few questions asked: there must be robust face to face welfare checks for those who do not attend.

Once back at school, many children may disclose abuse that occurred during closure, and children’s services may struggle to meet demand. As months will have passed since the abuse, there may be little physical evidence to support allegations, in turn reducing the weight of corroborative evidence to support child protection measures and risking children feeling they are not believed.

Child abuse and neglect carries long-term risks for cumulative physical and mental health problems,16 17 and without intervention a cycle of intergenerational poor parenting, abuse and neglect may result.18 There were 30 fewer CPME referrals than expected during 2020: given that Birmingham accounts for 2% of children referred for social care assessment nationally1 we estimate that there are approximately 1500 (95% CI 538 to 2192) potentially abused or neglected children in England who remain hidden from services. This number may be considerably greater with the suspected rise in rates of child abuse during lockdown. We face an epidemic of unreported, unrecognised child abuse and neglect with long-term implications for society as a whole. Getting all children back into school will reduce the risk, but may not undo the harm that has already occurred. Should there be a further lockdown, safeguards must be put in place to prevent vulnerable children coming to harm.

Unanswered questions and future research

We need to continue to evaluate CPME referral patterns and outcomes as children return to school, to help understand the hidden harms from COVID-19. There should be robust analyses of inpatient NAI cases to determine any increase in severe injuries. It is disappointing that these data need to be studied in local areas, some of which have very small numbers. A national data and analytics system would be very helpful. The significant decrease noted in girl referrals may simply be due to small numbers, but warrants further investigation as to whether this trend continues and if so, why. Research should include hearing children’s lived experiences so that appropriate safeguards can be put in place should schools have to close in future. Longer-term research is needed to ascertain and treat the mental health and behavioural outcomes that may result from abuse and neglect during school closures. As ‘child safeguarding is everyone’s business’19 learning how to protect children during an event such as COVID-19 should be a multiagency process. If there are further school closures the relative importance of hospital doctors, social workers and family members increases. Media communications could be used with effect to highlight this in hospital emergency departments for example. Mandatory regular visits to vulnerable children could be considered. Perhaps the National Safeguarding Practice Review Panel could take these ideas forward.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @bulawayojulie

Contributors: JG conceived the idea, the protocol was designed by JG, GD, JT, JA and IA. The data extraction tool was piloted, revised then used for data extraction by JG, GD, HC, JA, IA, ET, EEHT, CM and EB. The data analysis was undertaken by JG, NH and MP. Drafts of the paper were written by JG, GD, NH and JT with all authors contributing. Information for the paper came from the clinical records for each child. JG is guarantor of the article. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: JG is funded by West Midlands Clinical Research Network (NIHR) as a Clinical Trials Scholar. MP is supported by the NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Birmingham. The University of Birmingham provided the Article Processing Charge.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The University of Birmingham funded the article processing charge.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study involved clinicians analysing routinely collected patient data, from patients within their own clinical service, it therefore does not require HRA ethical approval. The study was approved by the Research and Innovation Department in Birmingham Community Healthcare Trust.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. Data are drawn from clinical child protection reports of individual children and cannot be shared. The disaggregated and anonymised abstraction files may be shared at reasonable request from the first author.

References

- 1.Department for Education Characteristics of children in need: 2018 to 2019, 2019. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/843046/Characteristics_of_children_in_need_2018_to_2019_main_text.pdf [Accessed 23 Jun 2020].

- 2.Barlow J, Woodman J, Bach-Mortensen A, et al. . The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on services from pregnancy through age 5 years for families who are high risk or have complex social needs. NIHR Policy Research Unit Children and Families, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.legislation.gov.uk Children act 1989 c.41 Part 5 section 47. UK public General acts, 1989. Available: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1989/41/section/47#:~:text=47%20Local%20authority’s%20duty%20to%20investigate.&text=(2)Where%20a%20local%20authority,or%20promote%20the%20child’s%20welfare [Accessed 18 Jun 2020].

- 4.Royal College of Nursing Safeguarding children and young people: roles and competencies for healthcare staff. Intercollegiate document, 2019. Available: https://www.portsmouthscp.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Intercollegiate-Doc-2019.pdf [Accessed 18 Jun 2020].

- 5.Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Child protection companion (Chapter five. London: RCPCH, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas A, Mott A. Child protection peer review for doctors who safeguard children. Royal College of paediatrics and child health, 2009. Available: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/peer-review-safeguarding

- 7.Birmingham City Council Population and census, 2018. Available: https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/info/20057/about_birmingham/1294/population_and_census/2 [Accessed 21 Jun 2020].

- 8.Birmingham Children Safeguarding Partnership Annual report 2018-2019. BCSP, 2019. Available: http://www.lscpbirmingham.org.uk/recent-publications/bscb-annual-report-2018-19?highlight=WyJhbm51YWwiLCJyZXBvcnQiLCJhbm51YWwgcmVwb3J0Il0=

- 9.Crawley E, Loades M, Feder G, et al. . Wider collateral damage to children in the UK because of the social distancing measures designed to reduce the impact of COVID-19 in adults. BMJ Paediatr Open 2020;4:e000701. 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department for Education Attendance in education and early years settings during the coronavirus outbreak - GOV.UK, 2020. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-attendance-in-education-and-early-years-settings [Accessed 21 Jun 2020].

- 11.Sidpra J, Abomeli D, Hameed B, et al. . Rise in the incidence of abusive head trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dis Child 2020:319872. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhopal S, Buckland A, McCrone R, et al. . Who has been missed? dramatic decrease in numbers of children seen for child protection assessments during the pandemic. Archives of disease in childhood, 2020. Available: https://adc.bmj.com/content/early/2020/06/17/archdischild-2020-319783 [Accessed 20 Jun 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.The PLOS Medicine Editors Observational studies: getting clear about transparency, 2014. Available: https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001711 [Accessed 22 Jun 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Sidebotham P, Brandon M, Bailey S, et al. . Pathways to harm, pathways to prevention: a triennial analysis of serious case reviews 2011-14. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/533826/Triennial_Analysis_of_SCRs_2011-2014_-__Pathways_to_harm_and_protection.pdf [Accessed 3 Jul 2020].

- 15.Brandon M, Sidebotham P, Belderson P, et al. . Complexity and challenge: a triennial analysis of serious case reviews 2014-17. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/869586/TRIENNIAL_SCR_REPORT_2014_to_2017.pdf [Accessed 3 Jul 2020].

- 16.Chandan JS, Keerthy D, Zemedikun DT, et al. . The association between exposure to childhood maltreatment and the subsequent development of functional somatic and visceral pain syndromes. EClinicalMedicine 2020;23:100392. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandan JS, Thomas T, Gokhale KM, et al. . The burden of mental ill health associated with childhood maltreatment in the UK, using the health improvement network database: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6:926–34. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30369-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Widom CS, Czaja SJ, DuMont KA. Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: real or detection bias? Science 2015;347:1480–5. 10.1126/science.1259917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.HM Government Working together to safeguard children a guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children, 2018. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/779401/Working_Together_to_Safeguard-Children.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-042867supp001.pdf (100.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-042867supp002.pdf (157.4KB, pdf)