Abstract

Over 150 jet engine power‐loss and damage events have been attributed to a phenomenon known as Ice Crystal Icing (ICI) during the past two decades. Attributed to ingestion of large numbers of small ice particles into the engine core, typically these events have occurred at high altitudes near large convective systems in tropical air masses. In recent years there have been substantial international efforts by scientists, engineers, aviation regulators and airlines to better understand the relevant meteorological processes, solve critical engineering questions, develop new certification standards, and devise mitigation strategies for the aviation industry.

One area of research is the development of nowcasting techniques based on available remote sensing technology and cloud models to identify potential areas of high ice water content (HIWC) and enable the provision of alerts to the aviation industry. An international consortium of researchers has investigated various methods for detecting the HIWC conditions associated with ICI. Multiple techniques have been developed using geostationary and polar orbiting satellite products, numerical weather prediction model fields, and ground based radar data as the basis for HIWC products. Targeted field experiments in tropical regions with high incidence of ICI events have provided data for product validation and refinement of these methods.

Beginning in 2015, research teams have assembled at a series of bi‐annual workshops to exchange ideas and standardize methods for evaluating performance of HIWC detection products. This paper provides an overview of the approaches used and the current skill for identifying HIWC conditions. Recommendations for future work in this area are also presented.

IMPACT OF ICE CYSTALS ON AVIATION OPERATIONS.

Ingestion of large amounts of ice crystals by jet engines, known as the Ice Crystal Icing (ICI) hazard, appears to be the culprit in over 150 jet engine power‐loss and damage events during the past two decades (Fig. 1). Typically occurring near tropical convective systems at high altitudes, heated inlets used by an aircraft’s Air Data System also appear to be vulnerable to high IWC (Ice Water Content) conditions. Although the heat within an engine or inlet would presumably prevent any ice build‐up, analyses of engine power‐loss events attributed to ICI together with wind tunnel testing suggest that significant amounts of ice can accrete inside sensitive parts of an aircraft engine. Ice accretion and subsequent ice shedding into engine cores during flight can adversely affect engine performance and damage engine components.

Figure 1:

Locations of confirmed Ice Crystal Icing Events as of 2015. Adapted from M. Bravin, The Boeing Corp.

The occurrence of engine power‐loss under atmospheric conditions not formerly recognized as hazardous initiated investigation of the clouds, convection, and ice crystals associated with ICI events in the early‐mid 2000s. Analyses of the meteorological conditions associated with these events reveals a number of common attributes. ICI hazards tend to occur near cores of deep convection and associated cirrus anvils. Onboard weather radar reflectivity at flight level is generally low for these events, suggesting that small ice crystals constitute the bulk of the ice mass encountered. Areas of heavy precipitation below flight level are sometimes observed. Any reports of turbulence are generally light to moderate, and there is no significant ice accretion on the airframe.

Following the analysis of ICI events, an international consortium of researchers was assembled to improve understanding of the scientific and engineering aspects of ice crystal icing. The USA led High Ice Water Content (HIWC) and the European High Altitude Ice Crystal (HAIC) projects have brought together researchers with aviation engineers, operators and regulators from Europe, North America, and Australia. Their objectives are to develop a better understanding of the relevant meteorology, solve critical engineering questions, develop new aircraft certification standards, and formulate mitigation strategies for the aviation industry. Sponsored by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the European Union 7th Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development (FP7), NASA, the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM), Transport Canada, Airbus, and Boeing, multiple research teams are funded to investigate the meteorological processes associated with high IWC. A central objective of these efforts is to understand the dynamic, thermodynamic, and microphysical cloud processes that result in potentially hazardous concentrations of ice crystals in some convective clouds.

DETECTION OF HIGH IWC CONDITIONS.

A current area of active research within the international consortium is the development of high IWC satellite detection and nowcasting techniques based on available passive and active remote sensing technology and numerical weather prediction (NWP) models. These techniques attempt to identify areas of high IWC and could enable the provision of alerts to the aviation industry. Such information is needed because, while new engine certification standards may largely mitigate the risks associated with ICI for future aircraft engines, there is a large current fleet which will be operating for many years. Thus, there is a recognized need for nowcasting guidance products to support flight planning and management of the strategic and tactical response for these aircraft.

Various research teams are investigating methods for detecting the high IWC conditions associated with ICI. Multiple techniques have been developed using geostationary and polar orbiting satellite products, NWP model fields, and ground based radar data as the basis for high IWC warning products (Table 1). Described below are the approaches of teams within the original HIWC‐HAIC research partnership. It is noted, however, that additional teams are conducting related research and development.

Table 1:

HIWC Diagnostic Products

| Product Name (developer) | Input Data Type(s) | Output Field |

|---|---|---|

| HIWC Mask (KNMI) | CPP Satellite Products | Yes/No HIWC |

| DARDAR (CNRS) | CloudSat, CALIPSO | IWC Vertical Profiles |

| PHIWC (NASA) | Overshooting Cloud Top / Anvil Texture Detection, LaRC SatCORPS, GEO Cloud Property Retrieval | HIWC Potential |

| ALPHA (NCAR) | NWP Model, Groundbased Radar, GEO satellite products | HIWC Potential |

| RDT (Météo‐France) | GEO satellite data (main input data), NWP, Lightning | Areas of rapidly developing convection |

MSG‐CPP High IWC Mask.

KNMI developed a geostationary satellite data product for identifying atmospheric conditions thought to favor ICI. Using daytime retrievals of cloud top height, cloud top temperature, and condensed water path from the Cloud Physical Properties (CPP) algorithm, the method sets thresholds on each variable to assemble a mask indicating areas of high IWC. Analysis of the High IWC Mask reveals that such conditions are frequently identified in mesoscale convective systems, tropical waves, hurricanes, extensive dense tropical cirrus, but also mid‐latitude frontal zones. The mask was successfully implemented on near‐real‐time imagery from various geostationary satellites. It has been evaluated against measurements from several field campaigns, has been used for real‐time field campaign planning purposes, and applied to construct climatologies of the occurrence of ICI conditions. The High IWC Mask is currently available via the KNMI MSG‐CPP webportal (http://msgcpp.knmi.nl). The algorithm was also adapted to low orbit MODIS observations and has been integrated in the Rapidly Developing Thunderstorms (RDT) data product (see below).

DARDAR products.

The DARDAR (raDAR/liDAR) product provides cloud properties by combining, through a synergistic variational algorithm, coincident spaceborne measurements of both CloudSat (95 GHz) radar and the CALIPSO (532 & 1064 nm) lidar, both instruments being part of the low orbit A‐Train mission. The DARDAR algorithm provides amongst several retrieved parameters vertical profiles of IWC, effective radius, particle size distribution, cloud phase and cloud classification along the vertical of the spacecraft. The DARDAR product makes the most of the lidar sensitivity to highly concentrated small ice crystals and the capability of the radar to penetrate optically thick ice clouds. The DARDAR product was used not only to statistically and geographically document at the global scale the occurrence of high IWC, whatever its vertical altitude, but also to tune and validate other high IWC products. A similar, but radar‐ based only, algorithm was applied to the the RAdar SysTem Airborne (RASTA) cloud radar observations collected during various field campaigns, providing closure between in situ and airborne measurements.

NASA Langley Research Center (LaRC) Probability of HIWC (PHIWC).

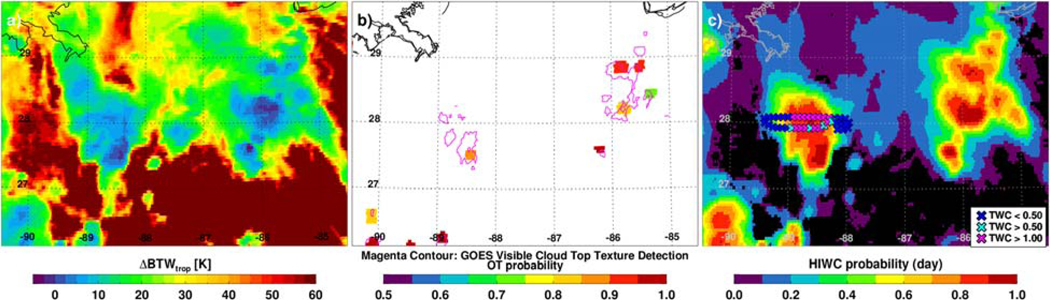

In‐situ IWC observations collected across 50 aircraft flights during three field campaigns (described below) were used to identify GOES and MTSAT‐1R satellite‐derived parameters coincident with high IWC. Analysis of these flights show 1) an exponential IWC increase during flight within 40 km of a convective updraft region, 2) an exponential IWC increase during flight within or beneath increasingly cold cloud tops, normalized by the regional Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) model tropopause temperature (Fig. 2a), and 3) a linear IWC increase with increasing cloud optical depth (daytime only) derived using the LaRC Satellite ClOud and Radiative Property retrieval System (SatCORPS). These relationships were used to derive fuzzy logic membership functions that serve as the foundation for the NASA LaRC Probability of High IWC (PHIWC) product (Fig 2c). Automated pattern recognition of overshooting cloud tops and anvil texture are used to define convective updraft regions (Fig 2b). The PHIWC product is designed to operate during both day and night, and can be generated using any global polar‐orbiting or geostationary visible/IR imager.

Figure 2:

(a) Tropopause-relative GOES-14 IR brightness temperature (GOES minus tropopause). Cool colors indicate cloud tops near to or above the tropopause. (b) GOES IR overshooting top detection probability (color shading, values > 0.7 shown) and visible texture detection (magenta contours), (c) NASA LaRC Probability of High Ice Water Content (PHIWC) overlaid with a one-hour segment of IKP2 total water content (TWC) collected by the NASA DC-8 aircraft, centered on a GOES-14 image on 16 August 2015 at 1745 UTC during the 2015 Ft. Lauderdale flight campaign.

Algorithm for the Prediction of HIWC Areas (ALPHA).

A 3‐dimensional diagnostic tool that uses operationally available satellite data, NWP model data, and ground based radar data (where available) as input, ALPHA was developed at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. The 3‐dimensional NWP model and radar data are blended with the 2‐dimensional satellite data via a set of fuzzy logic membership functions that exploit the strengths of each data set. A machine learning technique is applied to tune the algorithm using research aircraft measurements in high IWC conditions. A technique known as Particle Swam Optimization is used to select specific input variables, define membership functions, and determine weighting factors for optimal blending of the various data. The satellite‐based component of the algorithm locates high, cold cloud tops with large optical depths. NWP model fields are used to identify areas of potential convection using updrafts, convective precipitation, and condensate fields. Model temperature profiles bound the vertical extent of glaciated cloud conditions. The radar component of ALPHA detects active updrafts, high reflectivity and height of the convective clouds. Output from ALPHA is a 3‐dimensional gridded field of HIWC Potential (which can be thought of as an uncalibrated probability). The HIWC Potential field consists of output based on satellite, model, and radar data where radar data are available, and on satellite and model data only where radar data are not available. An example of HIWC Potential is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3:

NCAR’s ALPHA HIWC Potential product (gray scale indicates maximum value in vertical column) in the Gulf of Mexico on 16 August 2015 at 1745 UTC. The black contour encloses an area with HIWC Potential > 0.2. Color scale indicates ice water content along a one-hour flight segment of the NASA DC-8, as was also shown in Figure 2c.

Rapidly Developing Thunderstorms (RDT).

RDT (Rapidly Developing Thunderstorm) software is developed by Météo‐France in the framework of Eumetsat’s Satellite Application Facility for Nowcasting (NWCSAF). RDT uses brightness temperatures from geostationary satellites with the option of using NWP (Numerical Weather Prediction) products or lightning data. RDT detects, tracks and extrapolates thunderstorms cells. RDT also characterizes observed systems with different attributes such as cooling rate, top of thunderstorm, horizontal extension, etc. High IWC values are often associated with deep convection and especially strong updrafts that inject significant quantities of water into the upper troposphere. RDT has been operated for all HAIC or HAIC/HIWC field campaigns.

FIELD EXPERIMENTS.

A series of field experiments in tropical regions with high incidence of ICI events provided research aircraft data for product validation and refinement of nowcasting methods. The HIWC and HAIC projects collaborated to conduct experiments in Darwin, Australia (23 flights by the SAFIRE Falcon 20 in Jan‐Mar 2014; Fig. 4) and Cayenne, French Guiana (17 flights by the SAFIRE Falcon 20 and 10 flights by the Canadian Convair 580 during May 2015). In August 2015, a NASA‐led HIWC team carried out 10 research flights of the NASA DC‐8 aircraft for the HIWC Radar Study based in Ft. Lauderdale, FL. The HAIC project conducted a subsequent experiment with the Airbus A340 MSN1 flight test aircraft in Darwin and Reunion Island in January 2016. Some of the products described in aforementioned sections were used for flight planning and operations.

Figure 4:

(top) Operating area of the HAIC-HIWC Darwin flight campaign (yellow polygon) with groundbased radar coverage indicated by gray rings, including the research CPOL radar (blue ring). The red ring shows a 300 nmi distance reference; (middle) the SAFIRE Falcon 20 aircraft prepares for a research flight; (bottom) monsoon convection sampled within the Darwin operating area. Photos provided by T. Ratvasky.

The payload for all experiments included a suite of cloud microphysics probes, total water content (TWC, synonymous with IWC in glaciated conditions) sensors, and cloud radar. Of particular interest for the nowcast product development efforts are measurements of TWC from a newly developed isokinetic evaporator known as the Isokinetic Probe (IKP2) and an existing hot wire probe (ROBUST probe), as well as vertical IWC profiles from the airborne RASTA cloud radar.

COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH.

Beginning in 2015, the HAIC and HIWC nowcasting research teams have assembled at a series of dedicated workshops and break‐out sessions associated with HAIC‐HIWC team meetings. The purpose of these meetings is to foster international collaboration on development of high IWC diagnosis and forecasting methods. Meeting objectives have focused on sharing progress toward development of global HIWC products and standardizing techniques for evaluating performance of the products. Table 2 lists meeting dates and locations. The initial meetings featured presentations by each group describing methods used for high IWC detection. Subsequent discussions allowed participants to understand similarities and differences among the various approaches and to exchange ideas. In advance of the later workshops, organizers identified cases of interest from the field campaigns. Each group analyzed the assigned cases using its own method for high IWC detection, and brought results to the meetings for comparison and feedback.

Table 2:

Location and dates of HIWC Satellite and Nowcasting Workshops hosted by the HIWC-HAIC partners

| Location | Date |

|---|---|

| Toulouse, France | Oct 2015 |

| Melbourne, Australia | Nov 2015 |

| Toronto, Canada | May 2016 |

| Toulouse, France | Sept 2016 |

| Capua, Italy | Dec 2016 |

| Toulouse, France | Nov 2017 |

PRODUCT PERFORMANCE.

One outcome of these workshops is recognition that validation of high IWC products is complex. The work done by the various HIWC‐HAIC teams demonstrates that assessing performance of these products and comparing them in a meaningful way is not straightforward. The challenges arise from differences in product and data attributes as well as validation approaches. Performance statistics are affected by various issues such as:

Results are sensitive to assumptions used, e.g., the IWC threshold used to define high IWC.

Different criteria may be used to co‐locate in situ data with satellite/model/radar data and to account for spatio‐temporal differences in the data sets.

Some products are two‐dimensional while others are three‐dimensional.

- Products have differing objectives, for example:

- RDT was originally developed to identify developing convective systems, and has since been tailored for high IWC detection.

- The MSG‐CPP High IWC Mask was designed to identify high IWC conditions, but only provides a binary (yes/no) indicator based on the maximum IWC anywhere in a cloud.

- PHIWC and ALPHA estimate the potential for high IWC on a scale from 0‐1.

The HIWC‐HAIC teams have worked toward consistent evaluation methods where possible (e.g., issues (1) and (2) noted above), but inherent differences in the various approaches continue to complicate comparison of product performance. Nevertheless, it is still important for the community to gain a basic understanding of the accuracy of existing products. The KNMI high IWC Mask product gives a typical probability of detection (POD) around 60‐80%, with a similar false alarm ratio when compared with DARDAR measurements of IWC (Fig. 5). The POD could be significantly increased (> 90%) or the false alarm ratio (FAR) could be significantly decreased (<30%) by considering the differences in spatial footprint of the DARDAR measurements compared to the geostationary satellite measurements, disregarding atypical viewing angles and solar zenith angles, and considering the particular cloud water profile shape. The LaRC PHIWC and ALPHA HIWC Potential products attempt to pinpoint where within deep convection high IWC conditions are likely, a differing goal relative to the KNMI product which masks areas where high IWC is possible throughout the cloud vertical depth. Both PHIWC and ALPHA have been verified against airborne TWC measurements from the IKP2. The two‐dimensional PHIWC product gives a POD ranging from 60‐80% and a false alarm rate of 20‐35%, with best performance offered during daylight hours when cloud optical depth and visible texture retrievals are available and for extremely high IWC values (e.g. > 2.0 gm−3). A PHIWC time series derived from GOES‐14 1‐min super rapid scan observations (Fig. 6) shows that high IWC conditions (in situ total water content > 0.5 gm−3) can be resolved quite well. The 3‐dimensional ALPHA HIWC Potential product shows similar statistics when verified against a reserved set of independent flight‐level data from the three field campaigns (i.e., data not used for training of the algorithm). For example, with an assumed HIWC Potential threshold of 0.25 and an IWC threshold of 0.5 gm−3, ALPHA POD is 76% and FAR is 25% in primarily daytime conditions and where ground‐based radar data are available. Figure 7 shows the relationship between measured IWC and HIWC Potential for 49 flights during three field campaigns as estimated by ALPHA. RDT has been mainly compared with IWC measurements from the Robust Probe during the Cayenne field campaign. When RDT cells are matched with IWC measurements, it appears that (for 11 out of 16 flights) 70% of values of IWC above 1.0 gm−3 fall within a RDT cell. For 4 flights, over 90% of high IWC values fall within a RDT cell.

Figure 5:

Performance statistics for the MSG-CPP HIWC Mask based on DARDAR IWC profile maximum values. Adapted from deLaat et al. (2017).

Figure 6:

(top) In-situ total water content (TWC) observations from the IKP2 sensor collected on 16 August 2015 aboard the NASA DC-8 aircraft during the Ft. Lauderdale flight campaign. IKP-2 TWC is averaged to 5-sec (grey) and 45-second (black) intervals. The 45-sec time window, when coupled with the DC-8 airspeed, better represents the area of a GOES satellite infrared channel pixel. (bottom) The LaRC Probability of High Ice Water Content (PHIWC) product based on inputs with (black) and without (grey) datasets derived using GOES visible channel information.

Figure 7:

Box plot showing relationship between measured TWC and HIWC Potential estimated by NCAR’s ALPHA which was objectively trained using airborne in situ data from the Isokinetic Probe for three field experiments as described in the text. The median (50th percentile) is indicated in red, the blue box extends from the 25th to 75th percentile, and the dashed lines extend to the minimum/maximum non-outlier values.

While the IWC threshold used to define high IWC is still under discussion by the research community and aviation regulators, values of 0.5 g/m3 and 1.0 g/m3 have been used to compile performance statistics. Currently, the in situ IWC threshold is the accepted metric within the ICI community. However, the community accepts this in part only because of the lack of comprehensive information about ICI events. In situ IWC exceeding the threshold value may be only one of the criteria required for ICI events to occur. For example, there is some indication that simply exceeding a particular IWC for a brief period of time may not be as hazardous to engines as a longer duration exposure to moderate and high IWC. In addition, there are differences in sensitive of specific engines to similar exposure to high IWC. Obtaining a better understanding of the relative importance of localized high IWC, exposure time in elevated IWC, and susceptibility of various jet engine types to the occurrence of ICI events is critical for improving and fine tuning the existing products. Unfortunately, this information is generally not provided by airlines and aircraft manufacturers to researchers, a circumstance which limits further improvement of high IWC detection and nowcasting techniques.

OPERATIONAL APPLICATIONS.

In response to the ICI hazard, researchers have responded with a collection of prototype methods for identifying high IWC conditions, and have verified the resulting products with available research data. The products exhibit reasonable probabilities of detection, but often with significant false alarm rates. Ongoing research will address the need for regional tuning of algorithms, vertical variation of high IWC conditions, and short‐term forecasting methods for predicting the ICI hazard. In addition, the integration of geostationary satellite data from multiple satellites (i.e., MSG, the GOES‐R series, and Himawari‐8) together with global NWP models allows for the provision of operational ICI guidance products with global coverage.

In parallel with the research the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) has recognized a requirement by the international aviation industry for HIWC guidance products and is working to develop service requirements. Outreach efforts are currently underway to introduce high IWC detection capabilities to weather forecasters and airline users. Under a joint effort by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, NCAR, and the FAA, a nowcasting trial is being conducted with real‐time ALPHA products provided to industry users. LaRC PHIWC and overshooting cloud top detection data is being provided to several NOAA national forecast centers and Central Weather Service Units to enable near real‐time identification of hazardous convection. RDT is now produced globally by Météo‐France using five geostationary satellites, and the product is available to aviation end‐users. Feedback from these users will be an important source of information for refining the capability and utility of these products in a real‐world setting.

The development of satellite and model based data products for identifying atmospheric conditions favorable for ICI allows for the construction of climatologies, i.e. spatiotemporal statistics of where ICI conditions are likely to occur. Within the HAIC project, for example, some effort has been put into constructing such a climatology, revealing clear spatio‐temporal patterns that could be used for strategic flight planning (Fig. 8). Seasonal occurrence statistics based on ALPHA output have been generated for the U.S. and northern Australia. Regional databases of overshooting cloud top detection, well correlated with areas of high IWC in deep convection during the aforementioned flight campaigns, have also been generated at NASA LaRC and could aid in flight planning.

Figure 8:

2005–2015 climatology of SEVIRI HIWC mask. Daytime only, colors indicate the relative number of occurrences where red shades represent the highest incidence of high IWC conditions.

RECOMMENDATIONS.

Working in the context of a larger international collaboration, the high IWC nowcasting researchers have demonstrated the value of synergistic effort toward a common goal. As noted by Pablo Perez Illana (HAIC project office, European Commission, Directorate‐General for Research & Innovation, Aviation), “the interdisciplinary, international and interactive approach is worth highlighting”. He notes that the HAIC‐HIWC collaboration brings together experts from numerous disciplines within the meteorology and aviation communities. It also serves as an example for successful transatlantic and multilateral collaboration, being the largest European Union co‐funded aviation research project with North America.

The sustained collaborative effort between international teams devoted to the high IWC nowcasting challenge has resulted in a set of prototype products for detecting ICI hazards. Continued development and improvement of product performance depends on access by researchers to detailed information on engine performance and meteorological conditions during actual ICI events, additional in situ IWC measurements collected in future field experiments, and integration of new satellite and NWP model products as they become available. Feedback from users in operational settings is needed to define usage concepts and methods for integrating high IWC products with other aviation weather products. Currently, the dependence of some of these products on satellite, radar, and NWP model products makes them useful for strategic planning, rather than tactical support, due to latency issues. Future efforts will benefit from further interaction with the aviation community to define product performance requirements, to determine how high IWC products can best support flight planning and operations, and to support the expected growing role of data analytics in aviation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.

The authors thank the organizers, collaborators, and sponsors of the HAIC and HIWC projects who enabled the collection of essential data sets for this work and provided support for development of these products.

The HAIC authors (De Laat, Defer, Delanoë, Grandin, Moisselin, Parol) have received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program in research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement n°ACP2‐GA‐2012‐314314.

The research conducted by one of the authors (Haggerty) is in response to requirements and funding by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the FAA. NCAR is sponsored by the National Science Foundation.

NASA HIWC research (Bedka) was supported by the Advanced Air Transport Technology Project within the NASA Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate Advanced Air Vehicles Program.

Contributor Information

Julie Haggerty, National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colorado.

Eric Defer, Laboratoire d’Aérologie, Université de Toulouse, CNRS, OMP, UPS, Toulouse, France.

Adrianus de Laat, KNMI, de Bilt, the Netherlands.

Kristopher Bedka, NASA Langley Research Center, Hampton, Virginia.

Jean‐Marc Moisselin, Météo‐France, Toulouse, France.

Rodney Potts, Bureau of Meteorology, Melbourne, Australia.

Julien Delanoë, LATMOS, IPSL, UVSQ, Guyancourt, France.

Frédéric Parol, LOA, Université de Lille – Sciences et Technologies, CNRS, Lille, France.

Alice Grandin, AIRBUS S.A.S., Toulouse, France.

Stephanie DiVito, FAA Wm. J. Hughes Technical Center, Atlantic City, New Jersey.

FOR FURTHER READING

- Adams E 2018: https://www.wired.com/story/testing‐boeings‐new‐engine/

- Aviation Safety Network, 2016: http://news.aviation‐safety.net/2016/04/23/faa‐orders‐engine‐icing-fixes‐for‐genx‐powered‐boeing‐787‐dreamliners/

- Bedka KM, and Khlopenkov K, 2016: A probabilistic pattern recognition method for detection of overshooting cloud tops using satellite imager data. J. Appl. Meteor. And Climatol. 55, 1983–2005, doi: 10.1175/JAMC-D-15-0249.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bedka KM, Allen JT, Punge HJ, Kunz M, and Simanovic D, 2018: A Long‐Term Overshooting Convective Cloud Top Detection Database Over Australia Derived From MTSAT Japanese Advanced Meteorological Imager Observations. J. Appl. Meteor. and Climatol, 57, 937–951, 10.1175/JAMC-D-17-0056.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bravin M, Strapp JW, and Mason J, 2015: An investigation into location and convective lifecycle trends in an ice crystal icing engine database, Tech. rep., SAE Technical Paper 2015‐ 01‐2130, SAE International, Warrendale, Pennsylvania, USA, doi: 10.4271/2015-01-2130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccaldi M, Delanoë J, Hogan RJ, Pounder NL, Protat A, Pelon J, 2013: From CloudSat‐CALIPSO to EarthCare: Evolution of the DARDAR cloud classification and its comparison to airborne radar‐lidar observations, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 118 (14), pp.7962–7981. [Google Scholar]

- Davison CR, Strapp JW, Lilie L, Ratvasky TP, and Dumont C, “ Isokinetic TWC Evaporator Probe: Calculations and Systemic Error Analysis”, 2016, 8th AIAA Atmospheric and Space Environments Conference, June 17, 2016, Washington, DC: AIAA‐4060; 10.2514/6.2016-4060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Laat A, Defer E, Delanoë J, Dezitter F, Gounou A, Grandin A, Guignard A, Meirink JF, Moisselin J‐M, and Parol F: Analysis of geostationary satellite‐derived cloud parameters associated with environments with high ice water content, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 10, 1359–1371, 10.5194/amt-10-1359-2017, 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delanoë J, and Hogan RJ, 2008: A variational scheme for retrieving ice cloud properties from combined radar, lidar, and infrared radiometer, J. Geophys. Res, 113, D07204, doi: 10.1029/2007JD009000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grandin A, Merle J‐M, Weber M, Strapp J, Protat A, and King P, 2014: AIRBUS Flight Tests in High Total Water Content Regions. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 10.2514/6.2014-2753 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grzych M, Tritz T, Mason J, Bravin M et al. , 2015: Studies of cloud characteristics related to jet engine ice crystal icing utilizing infrared satellite imagery, SAE Technical Paper 2015‐01‐2086, 2015, doi: 10.4271/2015-01-2086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty J, McDonough F, Black J, Cunning G, McCabe G, Politovich M, Wolff C, “A System for Nowcasting Atmosphereic Conditions Associated with Jet Engine Power Loss and Damage Due to Ingestion of Ice Particles,” AIAA Atmosphere and Space Environment Conference, New Orleans, USA, June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mason JG, Strapp JW, and Chow P, “The ice particle threat to engines in flight,” 44th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Reno, Nevada, 9–12 January 2006, AIAA; ‐2006‐206. [Google Scholar]

- Protat A, Delanoë J, Bouniol D, et al. , “Evaluation of Ice Water Content Retrievals From Cloud Radar Reflectivity and Temperature Using a Large Airborne In‐Situ Microphysical Database,” Journal of Applied Meteorology, Vol. 46, 2007, pp. 557–572. [Google Scholar]

- Rugg A, Haggerty J, McCabe G, Palikondra R, and Potts R, High ice water content conditions around Darwin: Frequency of occurrence and duration as estimated by a nowcasting model,” AIAA Atmosphere and Space Environment Conference, Denver, USA, June 2017. [Available online at 10.2514/6.2017-4472 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strapp JW, and Coauthors, 2016: The High Ice Water Content (HIWC) study of deep convective clouds: Report on science and technical plan. FAA Rep. DOT/FAA/TC‐14/31, 105 pp. [Available online at www.tc.faa.gov/its/worldpac/techrpt/tc14‐31.pdf.] [Google Scholar]

- Yost CR, Bedka KM, Minnis P, Nguyen L, Strapp JW, Palikonda R, Khlopenkov K, Spangenberg D, Smith WL Jr., Protat A, and Delanoe J, 2018: A prototype method for diagnosing high ice water content probability using satellite imager data, Atmos. Meas. Tech, 11, 1615–1637, 10.5194/amt-11-1615-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]