Abstract

To investigate the dynamical properties of the novel hybrid compound, lithium benzimidazolate-borohydride Li2(bIm)BH4 (where bIm denotes a benzimidazolate anion, C7N2H5−), we have used a set of complementary techniques: neutron powder diffraction, ab initio density functional theory calculations, neutron vibrational spectroscopy, nuclear magnetic resonance, neutron spin echo, and quasi-elastic neutron scattering. Our measurements performed over the temperature range from 1.5 to 385 K have revealed the exceptionally fast low-temperature reorientational motion of BH4− anions. This motion is facilitated by the unusual coordination of tetrahedral BH4− anions in Li2(bIm)BH4: each anion has one of its H atoms anchored within a nearly square hollow formed by four coplanar Li+ cations, while the remaining −BH3 fragment extends into a relatively open space, being only loosely coordinated to other atoms. As a result, the energy barriers for reorientations of this fragment around the anchored B–H bond axis are very small, and at low temperatures, this motion can be described as rotational tunneling. The tunnel splitting derived from the neutron spin echo measurements at 3.6 K is 0.43(2) μeV. With increasing temperature, we have observed a gradual transition from the regime of low-temperature quantum dynamics to the regime of classical thermally activated jump reorientations. The jump rate of the uniaxial 3-fold reorientations reaches 5 × 1011 s−1 at 80 K. Nearer room temperature and above, both nuclear magnetic resonance and quasielastic neutron scattering measurements have revealed the second process of BH4− reorientations characterized by the activation energy of 261 meV. This process is several orders of magnitude slower than the uniaxial 3-fold reorientations; the corresponding jump rate reaches ~7 × 108 s−1 at 300 K.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The alkali and alkaline-earth borohydrides have attracted significant attention as promising materials for hydrogen storage.1,2 These compounds form ionic crystals consisting of metal cations and tetrahedral BH4− anions. It is interesting to note that the tetrahedral BH4− anions can also exhibit a structure-directing effect by binding preferably via their edges. This feature may lead to unusual structures, including the porous zeolitic-like frameworks of magnesium and manganese borohydrides.3,4 Such porous borohydrides can store hydrogen in two forms: covalently bonded H atoms in BH4− groups and physically adsorbed H2 molecules in the pores.3 However, in contrast to zeolitic imidazolate frameworks showing a rich variety of different pore sizes and structures,5 borohydrides cannot be easily modified by functionalization of the building blocks. One of the possible ways to modify the structure and properties of borohydrides is to prepare hybrid compounds combining the inorganic BH4− anion and the organic imidazolate-based ligand. The first such compounds have been synthesized recently;6,7 although they fail to exhibit any pronounced porosity, their structural features are quite remarkable. In particular, in the lithium benzimidazolate-borohydride, Li2(bIm)BH4 (where the benzimidazolate anion, C7N2H5−, is denoted by bIm−), the BH4− anions appear to be somewhat isolated from the surrounding planar bIm− anions, being only loosely coordinated on one side to four Li+ ions.7 Such an open BH4− coordination sphere is unusual among known borohydride structures.2,8 This feature suggests low barriers for reorientational (rotational) motion of BH4− anions.

Reorientational motions of BH4− anions are known to contribute strongly to the balance of energies determining the thermodynamic stability of borohydrides. Therefore, information on the reorientational dynamics is important for understanding the fundamental properties of these compounds. The aim of the present work is to investigate hydrogen dynamics in Li2(bIm)BH4 using a set of complementary techniques: neutron powder diffraction (NPD), ab initio density functional theory (DFT) calculations, neutron vibrational spectroscopy (NVS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), neutron spin echo (NSE), and quasi-elastic neutron scattering (QENS). Our results are consistent with the existence of the low-temperature rotational tunneling of BH4− anions in Li2(bIm)BH4. Although rotational tunneling has been extensively studied for −CH3 and NH4+ groups,9,10 to the best of our knowledge, it has not been directly observed for BH4− anions in borohydrides due to the relatively large reorientational barriers typically present in these ionic compounds. Both NMR and neutron scattering results for Li2(bIm)BH4 are described in terms of a gradual transition from the regime of low-temperature quantum dynamics (i.e., rotational tunneling) to the regime of classical jump reorientations of BH4− anions at higher temperatures.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

The synthesis of the powdered Li2(bIm)BH4 sample was analogous to that described in ref 7. For neutron scattering measurements, the 11B-enriched sample was prepared using Li11BH4 from Katchem11 as a starting material; this leads to a significant reduction of the neutron absorption due to the 10B isotope in natural boron.

For NMR experiments, the sample was flame-sealed in a glass tube under 0.5 bar of nitrogen gas. NMR measurements were performed on a pulse spectrometer with quadrature phase detection at the frequencies ωH,B/2π = 14, 28, and 90 MHz (1H) and 28 MHz (11B). The magnetic field was provided by a 2.1 T iron-core Bruker magnet. A home-built multinuclear continuous-wave NMR magnetometer working in the range of 0.32–2.15 T was used for field stabilization. For rf pulse generation, we used a home-built computer-controlled pulse programmer, the PTS frequency synthesizer (Programmed Test Sources, Inc.), and a 1 kW Kalmus wideband pulse amplifier. Typical values of the π/2 pulse length were 2–3 μs for both 1H and 11B. A probehead with the sample was placed into an Oxford Instruments CF1200 continuous-flow cryostat using helium or nitrogen as a cooling agent. The sample temperature, monitored by a chromel-(Au-Fe) thermocouple, was stable at ±0.1 K. The nuclear spin–lattice relaxation rates were measured using the saturation–recovery method. NMR spectra were recorded by Fourier transforming the solid echo signals (pulse sequence π/2x−t−π/2y).

Neutron scattering measurements were performed at the National Institute of Standards and Technology Center for Neutron Research. Neutron powder diffraction (NPD) measurements were performed at 6 temperatures between 2.5 and 298 K on the BT-1 High-Resolution Neutron Powder Diffractometer12 using the Cu(311) monochromator [λ = 1.5397(2) Å; 3° ≤ 2θ ≤ 168°] with an in-pile collimation of 60 min of arc. Rietveld structural refinements were performed using the GSAS package.13 Neutron vibrational spectroscopy (NVS) measurements were performed at 4 K on the Filter-Analyzer Neutron Spectrometer (FANS)14 using the Cu(220) monochromator with pre- and post-collimations of 20′ of arc, yielding a full width at half-maximum energy resolution of about 3% of the neutron energy transfer. High-resolution inelastic and quasi-elastic neutron scattering (QENS) measurements were performed on three complementary instruments: the Disc Chopper Spectrometer (DCS)15 between 4 and 153 K using various incident neutron wavelengths (λ) of 1.8 Å (25.2 meV), 2.75 Å (10.8 meV), and 4.8 Å (3.55 meV) with respective elastic scattering resolutions of 2.04 meV, 275 μeV, and 118 μeV full width at half-maximum (fwhm) and respective maximum attainable Q values of around 6.56, 4.29, and 2.46 Å−1; the High-Flux Backscattering Spectrometer (HFBS)16 between 1.5 and 385 K using an incident neutron wavelength of 6.27 Å (2.08 meV) with a resolution of 0.8 μeV fwhm and a maximum attainable Q value of 1.75 Å−1, and the NGA neutron spin echo spectrometer (NSE)17 at 3.6, 20, and 30 K using an incident neutron wavelength of 5.0 Å (3.27 meV, Δλ/λ ≈ 0.17) for Fourier times up to 10 ns at a Q value of 1.65 Å−1, where coherent scattering contributions were negligible. Instrumental resolution function free of any contaminating low-energy inelastic or quasi-elastic scattering was determined from a geometrically identical V annulus. For DCS measurements containing broad quasi-elastic scattering, the 4 K sample spectrum was also sufficient for use as a resolution function. All neutron scattering data were analyzed using the DAVE software package.18

To aid the structural model refinements of the NPD data, first-principles calculations were performed within the plane-wave implementation of the generalized gradient approximation to density functional theory (DFT) using a Vanderbilt-type ultrasoft potential with Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange.19 A cutoff energy of 544 eV and a 2 × 4 × 4 k-point mesh (generated using the Monkhorst–Pack scheme) were used and found to be enough for the total energy to converge within 0.01 meV per atom. For comparison with the NVS measurements, simulated phonon density of states (PDOSs) were generated from the DFT-optimized structure using the supercell method (2 × 2 × 2 cell size) with finite displacements20,21 and were appropriately weighted to take into account the total neutron scattering cross-sections of H, 11B, Li, C, and N.

Structural depictions were made using Visualization for Electronic and Structural Analysis (VESTA) software.22 For all figures, standard uncertainties are commensurate with the observed scatter in the data, if not explicitly designated by vertical error bars.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structural Behavior and Vibrational Dynamics of Li2(bIm)BH4.

Prior room-temperature synchrotron XRD measurements of Li2(bIm)BH4 suggested a structure with orthorhombic symmetry, but the exact orientation of the tetrahedral BH4− anions within the lattice remained unknown.7 Energy-minimization of this orthorhombic (space group C2221) structure upon releasing the symmetry restrictions suggested a rather unusual BH4− anion orientation at 0 K, with one of the tetrahedral B–H bond axes extending into the adjacent near-square-planar hollow formed by four Li+ cations. This theoretical result was corroborated by Rietveld model refinement of the Li2(bIm)11BH4 NPD pattern collected at 2.5 K (see Figure S1 of the Supporting Information). Aside from the refined BH4− orientation, the resulting low-temperature refined structure is largely consistent with the previously reported, room-temperature, orthorhombic structural arrangement, but modified slightly by the presence of a small monoclinic distortion of the compound (space group C2/m, β = 90.56(1)°) away from orthorhombic symmetry. Figure 1 depicts this low-temperature monoclinic structure and high-lights the unusual open coordination of each BH4− anion that allows three of its four H atoms to remain largely unrestricted to undergo facile reorientations around the more anchored B–H bond axis.

Figure 1.

(a) View of the monoclinic (space group C2/m) unit-cell structure of Li2(bIm)BH4 determined from the 2.5 K NPD pattern of Li2(bIm)11BH4. Red, green, black, blue, and gray spheres denote the Li, B, C, N, and H atoms, respectively. Planar benzimidazolate (C7N2H5)− and tetrahedral (BH4) anions are both clearly distinguished. (b) Schematic highlighting the unusual coordination of each tetrahedral BH4− anion in Li2(bIm)BH4, with one B–H bond directed into a Li4 nearly square hollow, allowing for facile reorientations of the other three H atoms around this bond axis (as depicted by the dashed ellipse) without any significant steric interference from neighboring benzimidazolate anions.

At the increasingly higher temperatures measured (35, 50, 80, 198, and 298 K; see Figures S2–S6 of the Supporting Information), NPD data can still be well fitted using the C2/m model. However, the monoclinic distortion appears to decrease with increasing temperature. In particular, the angle β resulting from the fits changes from 90.56° at 2.5 K to 90.14° at 298 K. At room temperature, the monoclinic model (C2/m) fits the NPD data only slightly better than the orthorhombic models (C2221 and Cmcm). Temperature dependences of the monoclinic angle β and the unit-cell volume V resulting from the NPD fits are shown in Figure S7 of the Supporting Information. It can be seen that both β and V exhibit unusual behavior in the range 35–50 K, which suggests some subtle structural changes in this region. Another interesting feature of the NPD fits is that the thermal factors for three H atoms of the BH4 group are anomalously large at 2.5 and 35 K (see.cif files in the Supporting Information); this may be related to the unusual dynamical behavior, to be discussed below. It should also be noted that, in addition to the main monoclinic Li2(bIm)BH4 phase, neutron diffraction patterns indicate the presence of a residual Li(bIm) compound (space group Pmca) used in the synthesis. The content of this minor phase remains nearly constant (~11 wt %) at all temperatures.

The neutron vibrational spectrum for Li2(bIm)11BH4 at 4 K based on FANS measurements is shown in Figure S8 of the Supporting Information compared with the simulated PDOS from the DFT-optimized monoclinic structure, indicating overall good agreement between experiment and theory. Further information about the character, symmetry, and energies of the different phonon normal mode vibrations contributing to the simulated PDOSs can be found in the Supporting Information. We note that the level of agreement is sensitive to the exact orientation of the BH4− anions within the unit-cell structure.

Figure 2 displays the temperature behavior of the two normal mode vibrational features near 10.5 and 16.1 meV (measured in neutron energy loss with DCS using 1.8 Å incident neutrons), which are dominated by BH4− anion librational (torsional) motions around the Li4−anchored B–H bond axes (see the corresponding animation files in the Supporting Information). The energies of BH4− librational modes around other axes are located in the much higher range of 50–60 meV, and the BH4− bending modes in the range of 130–160 meV (see Figure S8 of the Supporting Information). The structure in Figure 1 shows that the BH4− anions are arranged in chains along the c direction (in alternating orientations of one up then one down, etc.) in association with the accompanying double-row chains of Li+ cations. For the 10.5 meV feature, the collection of BH4− torsional oscillations along each chain occurs in the same direction (in synchronization), whereas for the 16.1 meV feature, the directions of the oscillations for each successive BH4− along a given chain are reversed. Moreover, the lower-energy mode involves some additional noticeable minor motions from the benzimidazolate anions, whereas, the higher-energy mode is comprised almost entirely of BH4− torsional oscillations. It is evident that the appearance of this bimodal distribution of torsional energies (instead of a single normal mode energy) signals the presence of some degree of lattice-mediated coupling between BH4− rotors along the chains.

Figure 2.

Neutron vibrational spectra measured with DCS for Li2(bIm)11BH4 in the low-energy region, indicating the temperature behavior of the two normal mode vibrational features dominated by BH4− anion librational (torsional) motions around the Li4-anchored B–H bond axes.

Reorientational Dynamics of BH4 Anions.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Results.

The reorientational dynamics associated with the unusual coordination of BH4− anions in Li2(bIm)BH4 were first investigated by NMR. Measurements of the proton spin–lattice relaxation rate, , are known as a particularly effective method of probing H jump motion in borohydrides over wide dynamic ranges.23 For most of the studied borohydrides, the dominant relaxation mechanism is due to time-dependent dipole–dipole interactions between nuclear spins. The corresponding contribution to shows a maximum at the temperature at which the proton jump rate τ−1(T) becomes nearly equal to the nuclear magnetic resonance frequency ωH, i.e., when ωHτ ≈ 1. According to the standard theory,24 in the limit of slow motion (ωHτ ≫ 1), is proportional to , and in the limit of fast motion (ωHτ ≪ 1), is proportional to τ, being frequency-independent. If the temperature dependence of the jump rate τ−1 follows the Arrhenius law

| (1) |

where Ea is the activation energy and kB is the Boltzmann constant, the plot of ln vs T −1 is expected to be linear in the limits of both slow and fast motion with the respective slopes of −Ea/kB and Ea/kB.

The measured proton spin–lattice relaxation rate in Li2(bIm)BH4 exhibits two frequency-dependent peaks in the studied temperature range of 10–306 K (see Figure 3); one peak is observed near 270 K, and the other near 28 K. Such a behavior indicates a coexistence of at least two types of atomic motion with strongly differing characteristic jump rates. It should be noted that the two-peak temperature dependence of has been observed previously for a number of borohydride-based systems.25–28 However, the specific feature of Li2(bIm)BH4 is that one of the peaks occurs at unusually low temperature; this suggests the presence of an extremely fast H motion down to low temperatures.

Figure 3.

Temperature dependences of the proton spin–lattice relaxation rates measured at 14, 28, and 90 MHz for Li2(bIm)BH4.

Although boron atoms do not participate in the reorientational motion of BH4− anions, 11B spin–lattice relaxation measurements can probe the reorientations via the fluctuating 11B−1H dipole–dipole and electric quadrupole interactions. However, the recovery of the 11B nuclear magnetization in borohydrides often deviates from a single-exponential behavior;29–31 this can be attributed24 to the non-zero electric quadrupole moment of 11B. For Li2(bIm)BH4, the recovery of the 11B nuclear magnetization can be reasonably approximated by a sum of two exponential functions over the entire temperature range studied. The temperature dependence of the fast (dominant) component of the 11B spin–lattice relaxation rate, , at 28 MHz is shown in Figure S9 of the Supporting Information. It can be seen that the temperature dependence of also exhibits two peaks, and these peaks occur in the same temperature ranges as the corresponding peaks. Thus, the 11B relaxation results suggest that both peaks in Li2(bIm)(BH4) are associated with different types of motion of BH4− anions, not with some H motion in the benzimidazolate anions.

Figure 4 shows the measured proton relaxation rates at ωH/2π = 14 and 28 MHz in the region of the high-T peak as a function of inverse temperature. General features of the data in this region are consistent with the predictions of the standard theory,24 as discussed above. Thus, for parametrization of the data in this region, we have used the Arrhenius law (eq 1) and the standard relation between and τ (see, e.g., eq 1 of ref 32). The fit parameters are the activation energy Ea, the pre-exponential factor τ0 in the Arrhenius law, and the amplitude parameter determined by the strength of the fluctuating part of the dipole–dipole interactions. These parameters have been varied to find the best fit to the data at two resonance frequencies simultaneously. The results of the simultaneous fit over the T range of 198–306 K are shown by solid lines in Figure 4; the corresponding motional parameters are Ea = 261(4) meV and τ0 = 1.4(2) × 10−13 s. It should be noted that the Ea value derived from the fit is in the range of typical activation energies for BH4 reorientations in borohydrides.23,33 However, the amplitude of the high-T relaxation rate peak is lower than that typically observed in borohydrides.23,33

Figure 4.

Proton spin–lattice relaxation rates measured at 14 and 28 MHz in the region of the high-temperature peak as a function of inverse temperature. Solid lines show the simultaneous fit of the standard model to the data.

In the region of the low-temperature peak, measurements were performed at three resonance frequencies: 14, 28, and 90 MHz. Figure 5 shows the measured proton spin–lattice relaxation rates in this region as a function of inverse temperature. As can be seen from this figure, the behavior of near the peak significantly deviates from that predicted by the standard model for thermally activated atomic motion. In particular, the high-temperature slope of the vs T−1 plot appears to be steeper than the low-temperature slope, and the frequency dependence of near the peak is considerably weaker than that predicted by the standard model. The leveling-off of the relaxation rates toward a constant plateau below 16 K (Figure 5) can be attributed to an additional “background” contribution due to spin diffusion to paramagnetic impurities.34 Furthermore, the measured 1H NMR spectrum for Li2(bIm)BH4 does not exhibit any significant changes related to motional narrowing24 over the broad temperature range (6–298 K). Figure S10 of the Supporting Information shows the temperature dependence of the width ΔH (fwhm) of the 1H NMR line measured at 28 MHz. Even at 6 K, the experimental value of ΔH (30 kHz) is considerably smaller than that estimated on the basis of the second-moment calculations for the “rigid lattice” (53.1 kHz). This means that the dipole–dipole interactions for 1H spins in Li2(bIm)BH4 are partially averaged out even at very low temperatures. Such a behavior is typical of the case of rotational tunneling.35

Figure 5.

Proton spin–lattice relaxation rates measured at 14, 28, and 90 MHz in the region of the low-temperature peak as a function of inverse temperature. Solid lines show the simultaneous fit of the model based on eqs 2 and 3 to the data.

The usual approach to the description of rotational tunneling effects on the proton spin–lattice relaxation governed by fluctuating dipole–dipole interactions is based on the model introduced by Haupt.36 Taking into account the background contribution to the relaxation rate, B, the corresponding expression for can be written as

| (2) |

The first term in eq 2 with the relaxation strength C1 arises from fluctuations of the “intramolecular” dipole–dipole interactions due to transitions between the tunneling-split states of the rotor. This term contains the tunneling frequency ωt that determines the splitting, ℏωt, where ℏ is the reduced Planck constant. If ωt is much larger than the resonance (Larmor) frequency ωH, the first term becomes ωH-independent; this leads to the characteristic frequency-independent “shoulder” at the high-temperature slope of the peak.36−38 In the case of Li2(bIm)BH4, the observed frequency dependence of near the peak suggests that ωt is of the order of ωH.37 The second term in eq 2 with the relaxation strength C2 arises from fluctuations of the “intermolecular” dipole–dipole interactions; the form of this term corresponds to the classical expression for the spin–lattice relaxation rate. The correlation time τc for dipole–dipole interactions is determined by the lifetime of the tunneling states at low temperatures and by the mean H residence times at high temperatures; the temperature dependence of τc is usually approximated by the expression37

| (3) |

describing a smooth transition from quantum dynamics at low temperatures to classical behavior at higher temperatures. Here, E01 is the energy difference between the librational ground state and the first excited state, and Ea2 is the classical activation energy related to the potential barrier height. For parametrization of the experimental data in the region of the low-temperature peak, we have used the model based on eqs 2 and 3. The fit parameters (C1, C2, B, ωt, E01, Ea2, τ01, and τ02) have been varied to find the best fit to the data at the three resonance frequencies simultaneously. The results of the simultaneous fit over the temperature range of 10–54 K are shown by solid lines in Figure 5; the corresponding parameters are C1 = 1.1(1) × 109 s−2, C2 = 2.1(1) × 109 s−2, B = 0.60(3) s−1, ωt = 7.5(3) × 108 s−1, E01 = 17.7(8) meV, Ea2 = 44.1(2) meV, τ01 = 4.5(2) × 10−12s, and τ02 = 6.2(3) × 10−16s. Note that the value of ωt resulting from the fit is indeed close to the upper limit of the range of the Larmor frequencies ωH (8.8 × 107 to 5.7 × 108 s−1) in our experiments. In energy units, this ωt value corresponds to a splitting of 0.49 μeV. To verify the presence of this splitting, we have employed the neutron spin echo spectrometer NSE, which provides the best energy resolution among available neutron spectrometers.

Neutron Spin Echo.

The neutron spin echo technique directly probes the neutron energy changes in the scattering process using the neutron spin precession period in a magnetic field as the internal clock. The quantity measured by NSE is proportional to the intermediate scattering function I(Q, t)—the time Fourier transform of the scattering function S(Q, ω), where ℏω is the neutron energy transfer and ℏQ is the neutron momentum transfer. In our case, the scattering function is dominated by the incoherent part. For stochastic H motion, S(Q, ω) is represented by a single line centered at zero-energy transfer, and I(Q, t) should be a monotonically decreasing function of time which can often be described by an exponential decay or a sum of exponentially decaying functions.17 In the case of the tunnel splitting, in addition to the line centered at zero-energy transfer, S(Q, ω) should contain a number of lines centered at finite energy transfers; therefore, one can expect an oscillatory behavior of I(Q, t).

Figure 6 shows the results of NSE measurements (normalized by the resolution function) for Li2(bIm)(BH4) at Q = 1.65 Å−1 and increasing temperatures of 3.6, 20, and 30 K. It can be seen that at 3.6 and 20 K the intermediate scattering function contains an oscillatory part which is especially pronounced at 3.6 K. Such a behavior is direct evidence for the low-temperature tunnel splitting in Li2(bIm)(BH4). The period of the oscillations is determined by the splitting value, and the damping of the oscillations is determined by the width of the tunnel peaks and the incident neutron wavelength distribution. Another important parameter of the data is the elastic incoherent structure factor (EISF) which is defined as the ratio of the integrated elastic intensity to the total scattering intensity; this parameter determines I(Q, t) at long times. At T = 30 K, the oscillatory part of the intermediate scattering function completely disappears, and I(Q, t) can be described by a monotonically decaying function of time. Such a behavior reflects a gradual transition from the low-temperature rotational tunneling to the regime of classical reorientational jumps at higher temperatures.

Figure 6.

NSE intensity at Q = 1.65 Å as a function of the Fourier time for Li2(bIm)11BH4 at 3.6, 20, and 30 K. For the lowest two temperatures, the solid lines show model fits assuming the existence of Gaussian-shaped tunneling peaks in S(Q, ω) space, whereas for 30 K, the solid line shows the model fit for purely exponential decay of I(Q, t) associated with a single Lorentzian-shaped quasi-elastic line broadening in S(Q, ω) space.

For parametrization of the two lower-temperature NSE results, we have used the model with two Gaussian-broadened tunneling peaks, both with fwhm linewidths w, centered at ±ℏωt. The results of the fits taking into account a Gaussian-shaped incident neutron wavelength distribution are shown as solid lines in Figure 6. The corresponding fit parameters are ℏωt = 0.43(2) μeV, w = 0.18(7) μeV and EISF = 0.82(1) at 3.6 K, and ℏωt = 0.34(5) μeV, w = 0.66(4) μeV and EISF = 0.71(2) at 20 K. It should be noted that the low-temperature value of the tunnel splitting appears to be close to that derived from NMR. With increasing temperature, the splitting ℏωt is found to decrease, while the width w becomes larger. Such a behavior is typical of systems with the rotational tunneling,9,10 where the tunnel peaks gradually merge into the central line at higher temperatures.

At 30 K, the NSE data can be reasonably fitted by the model with a single quasi-elastic line with w = 0.51(7) μeV and EISF = 0.67(2), consistent with the expected gradual transformation from quantum rotational tunneling to classical stochastic jump reorientations.9

The observation of a single tunnel splitting of 0.43(2) μeV is consistent with the rotational tunneling occurring preferentially among three H atoms around a single 3-fold BH4− anion symmetry axis, rather than among all four tetrahedrally distributed H atoms, which would display additional tunneling lines as observed for other tetrahedrally symmetric rotors.9,10 Of course, the present result is expected and fully consistent with the unusual BH4− coordination to the Li4 cluster shown in Figure 1. More subtle details concerning the relationship between the neutron spin echo and neutron vibrational spectroscopy data are discussed in the Supporting Information.

Neutron Backscattering Spectroscopy (Low Temperatures).

Although the roughly 1 μeV instrumental resolution of HFBS makes it difficult to observe the submicrovolt BH4− rotational tunneling lines in Li2(bIm)BH4, they are nonetheless still evident as minor shoulders on the 1.5 K elastic scattering peak shown in Figure 7. Missing tunneling features are clearly manifested by the difference spectrum (fit-data) when only a resolution function and flat background are considered in the fitting procedure (see Figure 7a). Since the tunneling features are largely buried under the elastic peak, simultaneous fitting of their position, width, and intensities becomes problematic. For example, if a delta function is assumed for the two tunneling lines, then the observed intensities are lower than expected, and the value of the splitting is higher than expected. Figure 7b shows a typical fit to the data using the NSE results by fixing the tunnel splitting at ±0.43 μeV and assuming Gaussian-broadened lineshapes, both with linewidths of 0.18 μeV fwhm.

Figure 7.

HFBS data for Li2(bIm)11BH4 at 1.5 K fitted with a resolution-broadened delta function and flat background (a) without and (b) with a pair of 0.18 μeV fwhm, Gaussian-shaped, tunneling lines at ±0.43 μeV. (c) HFBS data for Li2(bIm)11BH4 at 35 K fitted with a sum of resolution-broadened delta and Lorentzian functions and flat background. Residual differences are plotted beneath the fitted spectra. Insets enlarge the region between ±2 μeV.

Figure 7c shows the transformation from quantum tunneling behavior (discrete tunneling peaks) toward classical stochastic 3-fold jump reorientations (quasi-elastic-like Lorentzian broadening) upon increasing the temperature from 1.5 to 35 K. Above 30 K, the QENS spectra could be adequately described by a delta function and a single Lorentzian component, both convoluted with the resolution function, above a flat background. The Lorentzian fwhm line width Γ was found to remain constant as a function of Q.

The temperature dependence of Γ in the range between 32 and 45 K can be satisfactorily approximated by the Arrhenius-type expression with the activation energy of 17.2(2) meV. The corresponding results are shown in Figure 8. This figure includes our data on the jump correlation frequencies obtained from various QENS and NMR experiments versus inverse temperature. For hydrogen reorientational jumps around the anchored B–H bond axis, the fundamental jump correlation frequency τ1−1 is proportional to Γ, τ1−1 = Γ/(2ℏ). This correlation frequency is expected to be equivalent to τ−1 derived from NMR experiments. Indeed, as can be seen from Figure 8, the HFBS results in the range 32–45 K are close to the NSE result at 30 K and to the points obtained from the low-T proton spin–lattice relaxation rate maxima.

Figure 8.

Arrhenius-type plots of the jump correlation frequencies obtained from various QENS and NMR experiments versus inverse temperature. Red symbols: points derived from the proton spin–lattice relaxation rate maxima at different resonance frequencies. Blue symbol: neutron spin echo result at 30 K. Green symbols: time-of-flight QENS results (DCS). Black symbols: backscattering QENS results (HFBS) for both the fast and slow jump processes. The inset shows the enlarged view of the HFBS results for the slow jump process. Solid red lines represent the fits of the proton spin–lattice relaxation results for the fast and slow processes. The solid black line represents the Arrhenius fit to the HFBS for the slow process. Dashed black and green lines show the Arrhenius fits to the HFBS and DCS data, respectively, for the fast process.

Neutron Time-of-Flight Spectroscopy.

To follow the fast BH4− reorientational motion to even higher temperatures, QENS spectra were collected on the time-of-flight neutron spectrometer DCS between 42 and 153 K. A representative spectrum is shown in Figure S11 of the Supporting Information. As for the lower-temperature HFBS spectra, all DCS spectra could be adequately approximated by a delta function and a single Lorentzian component, both convoluted with the resolution function, above a flat background. Again, the Lorentzian line width Γ was found to be Q-independent. The corresponding jump correlation frequencies resulting from the DCS spectra are included in Figure 8; the activation energy derived from this Arrhenius-like dependence is 18.0(2) meV. Although this activation energy appears to be close to that obtained from the HFBS data between 32 and 45 K, the actual Γ values derived from the DCS spectra are considerably higher than those derived from the HFBS spectra in the temperature range of partial overlap of the data. A possible reason for this discrepancy may be related to subtle structural changes observed between 35 and 50 K (see Figures S2–S4, and S7 of the Supporting Information). In particular, Figure S7 indicates a relatively sharp change in lattice distortion in this temperature region, which may ultimately affect the −BH3 rotational potential profile, resulting in further enhancement in reorientational mobility at higher temperatures. Note that the collapse of the −BH3 librational bands with increasing temperature in Figure 2 reflects the effects of the increasingly rapid reorientational motions that are measured on DCS. Besides invoking the structural-change arguments above, another possible reason may be related to the presence of a distribution of the reorientational jump rates. As discussed previously,39 in the presence of broad jump rate distributions, the standard analysis of QENS spectra is expected to underestimate the changes in the quasi-elastic line width with temperature.

To discuss the nature of the reorientational mechanism, we have to compare the experimental Q dependence of the elastic incoherent structure factor (EISF) with its calculated behavior for different possible models. For such a comparison, it is preferable to use the data at a short incident neutron wavelength, since these data allow us to access a broader Q range.

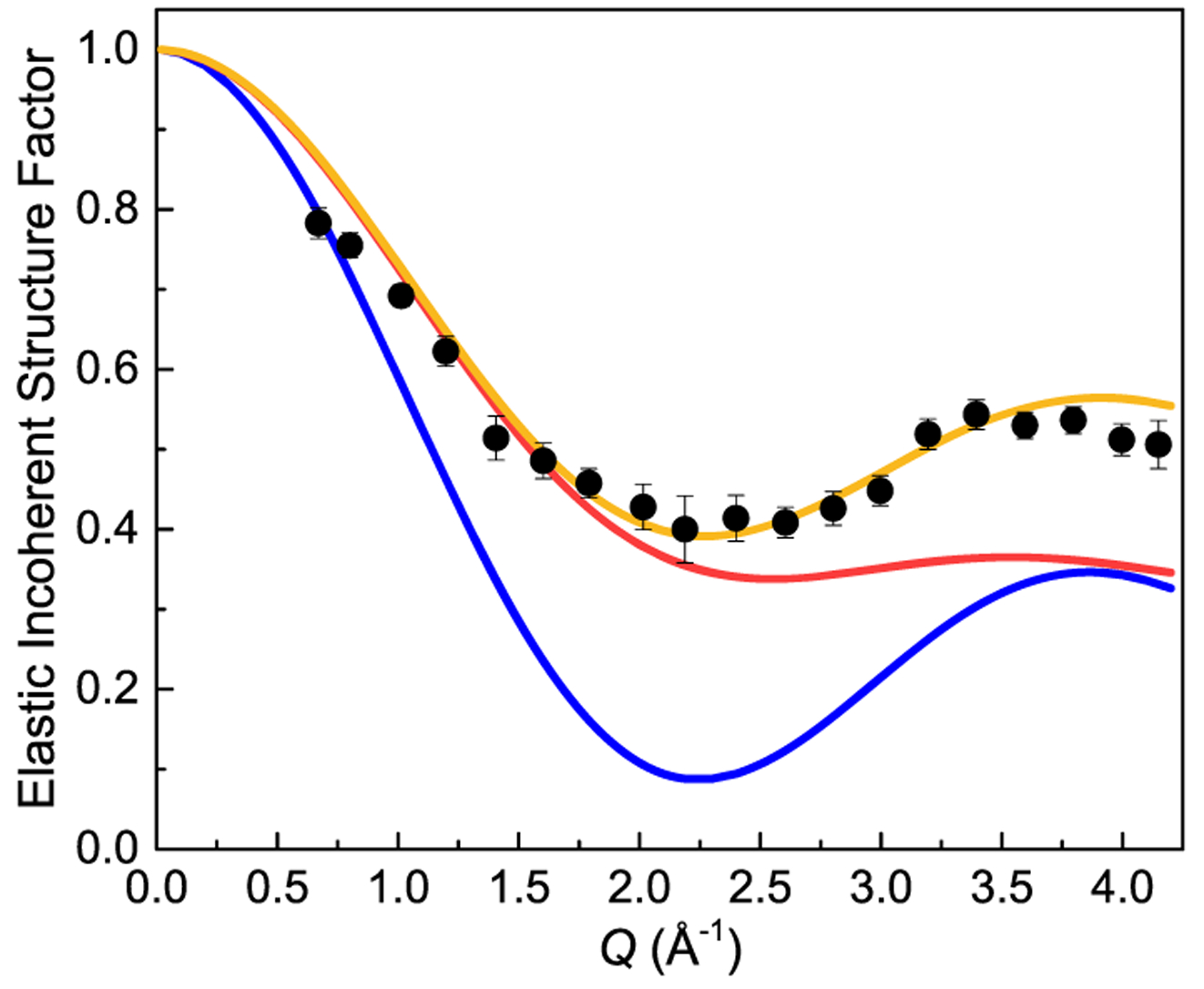

Figure 9 shows the Q dependence of the EISF for Li2(bIm)11BH4 at 80 K derived from the DCS data using the incident neutron wavelength of 2.75 Å. It should be noted that the EISF results shown in Figure 9 correspond to the contribution solely due to BH4− anions, i.e., after removing the extra elastic scattering contributions from the “immobile” H atoms associated with benzimidazolate anions both in the main compound and in the minor Li(bIm) impurity (see Figure S1 of the Supporting Information). The orange curve in Figure 9 shows the model Q dependence of the EISF for uniaxial 3-fold jumps of BH4− anions around the anchored B–H bond C3 axis40

| (4) |

where j0(x) is the zeroth-order spherical Bessel function equal to sin(x)/x, and d ≈ 2.0 Å is the jump distance between two H atoms in BH4−. It can be seen that the agreement between the experimental data up to Q ≈ 4.2 Å−1 and this 3-fold model is satisfactory. The alternative models include the uniaxial rotational diffusion around the anchored bond axis, which in the measured Q range can be well-approximated by considering 6-fold reorientations41

| (5) |

and tetrahedral tumbling of BH4− anions, which allows all associated hydrogen atoms to visit any of the four crystallographic H positions of the anion40

| (6) |

As can be seen from Figure 9, both the models of uniaxial rotational diffusion and the tetrahedral tumbling do not provide a reasonable description of the experimental results. It should be noted that, for the tetrahedral BH4− anion, the uniaxial C3 model (with one immobile hydrogen atom) happens to exhibit the same Q dependence of the EISF as the model of uniaxial 180° (2-fold) reorientations around one of the C2 symmetry axes (with no immobile hydrogen atoms). Both C3 and C2-type jump models are also consistent with the observed Q-independence of QENS linewidths Γ.42,43 Yet, based on the crystallographic structure and nature of the anion rotational potential, we can confidently discount this latter 2-fold jump mechanism. Hence, the observed EISF behavior corroborates the expected 3-fold jump mechanism of the anchored−BH3 fragments and indicates that, even at 80 K, they still undergo reorientational jumps between discrete 3-fold potential wells spaced 120° apart. This makes sense if most BH4− anions are still in their librational ground state at this temperature. At such a low temperature, it is enough to approximate the BH4− librational potential comprised of only two levels, i.e., the ground-state and first-excited-state levels. In this instance, the fraction of BH4− anions populating the ground-state level is given by the Fermi–Dirac distribution relation (1 + exp(–E01/(kBT))−1. At 80 K and an assumed librational excitation energy E01 of 13.3 meV, this ground-state fraction is indeed an overwhelming 87%.

Figure 9.

Elastic incoherent structure factor for BH4− anions in Li2(bIm)11BH4 as a function of Q. The experimental points (black circles) are determined from the DCS data (using the incident neutron wavelength of 2.75 Å) at 80 K. The curves represent the model of uniaxial 3-fold jumps of BH4− anions around the anchored B–H bond C3 axis (orange), the model of uniaxial rotational diffusion around the C3 axis (red), and the model of BH4− tetrahedral tumbling (blue).

Neutron Backscattering Spectroscopy (High Temperatures).

To probe the slower reorientational process (responsible for the high-temperature peak), we have performed neutron backscattering measurements up to 385 K. Figure 10 shows the HFBS neutron-elastic-scattering fixed-window scan (FWS) in heating from 4 to 385 K. The FWS reflects the temperature dependence of the neutron scattering intensity at zero-energy transfer. Between 4 and 25 K, the FWS intensity remains nearly constant as the tunneling peaks gradually collapse and broaden toward zero energy. At higher temperatures, the FWS intensity starts to fall sharply, since the classical quasi-elastic line broadening leads to a loss of zero-energy intensity. By about 40 K, the H jump rates reach ~1010 s−1, beginning to move outside the HFBS energy window. This is expected to lead to a certain leveling-off of the FWS intensity. However, the experimental FWS intensity continues to fall noticeably all the way up to 385 K due to the relatively large Debye–Waller factor associated with the three librating H atoms of the BH4− anions around the anchored B–H bond axis.

Figure 10.

Results of the neutron-elastic scattering fixed-window scan on HFBS for Li2(bIm)11BH4 upon heating at a rate of 1 K/min from 4 to 385 K at Q = 1.2 Å−1.

Between ~280 and 350 K, an additional minor intensity drop is also evident, which indicates the onset of a second reorientational jump process, presumably due to another type of BH4− reorientational motion according to the NMR results, at the frequency scale of the HFBS.

Additional QENS measurements were made on HFBS between 300 and 385 K to characterize the H jump rates and activation energy corresponding to this slower BH4− reorientational process. Again, the QENS spectra could be adequately fit with a delta function and a single Lorentzian component, both convoluted with the resolution function, above a flat background (see Figure S12 in the Supporting Information). Moreover, the quasi-elastic line width appeared to be Q-independent over the limited Q range accessed. The resulting values of H jump rates are shown in Figure 8; their temperature dependence in the range 300–385 K is well-described by the Arrhenius law with the fitted reorientation barrier of 261(1) meV. This value is identical to the activation energy of 261(4) meV determined from the NMR data for the slower reorientational process. It is reasonable to assume that the slower process corresponds to the reorientational exchange between the anchored H atom of the BH4− anion and one of the rapidly rotating H atoms in the −BH3 fragment. This type of composite reorientational mechanism was also observed for BH4− in both hexagonal LiBH4 (ref 44) and hexagonal LiBH4-LiI solid solution phases.41 No further effort was made to extract a composite EISF from the HFBS data since we would need an accurate assessment of the Q-dependent quasi-elastic scattering intensity from the rapidly reorienting −BH3 rotor, which is essentially hidden as part of the flat background and extends orders of magnitude outside the energy range of the instrument.

CONCLUSIONS

Our nuclear magnetic resonance and quasi-elastic neutron scattering experiments have revealed the exceptionally fast low-temperature reorientational motion of BH4− anions in lithium benzimidazolate-borohydride Li2(bIm)BH4. This motion is facilitated by the unusual coordination of tetrahydroborate groups in Li2(bIm)BH4: each BH4− anion has one of its H atoms anchored within a nearly square hollow formed by four coplanar Li+ cations, while the remaining −BH3 fragment extends into a relatively open space, being only loosely coordinated to other atoms. As a result, the energy barriers for reorientations of this fragment around the anchored B–H bond axis appear to be very small. At low temperatures, this uniaxial motion can be described as rotational tunneling. According to the neutron spin echo results, the tunnel splitting at 3.6 K is 0.43(2) μeV. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first well-documented case of rotational tunneling for BH4 groups. As the temperature increases from 3.6 to ~30 K, we observe a gradual transition from the regime of low-temperature quantum dynamics (rotational tunneling) to the regime of classical thermally activated jump reorientations. According to the neutron time-of-flight spectroscopy results, the reorientational jump rate reaches 5 × 1011 s−1 at 80 K. Measurements of the elastic incoherent structure factor at this temperature are consistent with the model of uniaxial 3-fold reorientations of the tetrahydroborate groups. Nearer room temperature and above, both NMR and QENS measurements have revealed a second BH4− reorientational process characterized by the activation energy of 261 meV. This process is several orders of magnitude slower than the uniaxial 3-fold reorientations; presumably, it corresponds to exchanges between the anchored H atom and the other three rapidly reorienting H atoms of the −BH3 fragment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Grant No. 19-12-00009). It was also supported, in part, by the DOE EERE under Grant No. DE-EE0002978 and the Belgian Fonds National pour la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS). Access to the High-Flux Backscattering Spectrometer and the Neutron Spin Echo Spectrometer was provided by the Center for High-Resolution Neutron Scattering, a partnership between the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the National Science Foundation under Agreement No. DMR-1508249. M.D. gratefully acknowledges support from the Hydrogen Materials—Advanced Research Consortium (Hy-MARC), established as part of the Energy Materials Network under the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (DOE EERE), Fuel Cell Technologies Office, under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308. F.M. gratefully acknowledges a supporting fellowship from the Belgian Fonds pour la Formation à la Recherche dans l’Industrie et l’Agriculture (FRIA).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b06083.

- NPD, NVS, NMR, and QENS data (PDF)

- Li2(bIm)BH4_2P5K (CIF)

- Li2(bIm)BH4_35K (CIF)

- Li2(bIm)BH4_50K (CIF)

- Li2(bIm)BH4_80K (CIF)

- Li2(bIm)BH4_180K (CIF)

- Li2(bIm)BH4_298K (CIF)

- Li2(bIm)BH4_2P5K_Cmcm (CIF)

- Li2(bIm)BH4_298K_C2221 (CIF)

- Li2(bIm)BH4_C2m_phonons_file (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Orimo S; Nakamori Y; Elisen JR; Züttel A; Jensen CM Complex Hydrides for Hydrogen Storage. Chem. Rev 2007, 107, 4111–4132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Paskevicius M; Jepsen LH; Schouwink P;Černý R; Ravnsbæk DB; Filinchuk Y; Dornheim M; Besenbacher F; Jensen TR Metal Borohydrides and Derivatives – Synthesis, Structure and Properties. Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46, 1565–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Filinchuk Y; Richter B; Jensen TR; Dmitriev V; Chernyshov D; Hagemann H Porous and Dense Mg(BH4)2 Frameworks: Synthesis, Stability and Reversible Absorption of Guest Species. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2011, 50, 11162–11166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Richter B; Ravnsbæk DB; Tumanov N; Filinchuk Y; Jensen TR Manganese Borohydride: Synthesis and Characterization. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 3988–3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Banerjee R; Phan A; Wang B; Knobler C; Furukawa H; O’Keeffe M; Yaghi OM High-Throughput Synthesis of Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks and Application for CO2 Capture. Science 2008, 319, 939–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Morelle F; Ban V; Veryasov G; Miglio A; Hautier G; Skoryunov RV; Babanova OA; Soloninin AV; Skripov AV; Fleutot B et al. Towards Nanoporous Hybrid Hydrides: The First Imidazolate Borohydride Compound. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed

- (7).Morelle FJ; Tumanov N; Babanova OA; Skoryunov RV; Soloninin AV; Skripov AV; Zhou W; Udovic TJ; Filinchuk Y Synthesis and Structure of Imidazolate Borohydrides Based on 2-Methylimidazolate and Benzimidazolate. Chem. - Eur. J

- (8).Filinchuk Y; Chernyshov D; Dmitriev V Light Metal Borohydrides: Crystal Structures and Beyond. Z. Kristallogr 2008, 223, 649–659. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Prager M; Heidemann A Rotational Tunneling and Neutron Spectroscopy: A Compilation. Chem. Rev 1997, 97, 2933–2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Verdal N; Udovic TJ; Rush JJ; Stavila V; Wu H; Zhou W; Jenkins T Low-Temperature Tunneling and Rotational Dynamics of the Ammonium Cations in (NH4)2B12H12. J. Chem. Phys 2011, 135, No. 094501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11). The mention of all commercial suppliers in this paper is for clarity and does not imply the recommendation or endorsement of these suppliers by NIST.

- (12).Stalick JK; Prince E; Santoro A; Schroder IG; Rush JJ Materials Science Applications of the New National Institute of Standards and Technology Powder Diffractometer In Neutron Scattering in Materials Science II; Neumann DA, Russell TP, Wuensch BJ, Eds.; Materials Research Society: Pittsburgh, 1995; Vol. 376, pp 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Larson AC; Von Dreele RB General Structure Analysis System, Report LAUR 86–748; Los Alamos National Laboratory: Los Alamos, NM, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Udovic TJ; Brown CM; Leao JB; Brand PC; Jiggetts RD; Zeitoun R; Pierce TA; Peral I; Copley JRD; Huang Q; et al. The Design of a Bismuth-Based Auxiliary Filter for the Removal of Spurious Background Scattering Associated with Filter-Analyzer Neutron Spectrometers. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 2008, 588, 406–413. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Copley JRD; Cook JC The Disk Chopper Spectrometer at NIST: A New Instrument for Quasielastic Neutron Scattering Studies. Chem. Phys 2003, 292, 477–485. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Meyer A; Dimeo RM; Gehring PM; Neumann DA The High Flux Backscattering Spectrometer at the NIST Center for Neutron Research. Rev. Sci. Instrum 2003, 74, 2759–2777. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Rosov N; Rathgeber S; Monkenbusch M Scattering from Polymers: Characterization by X-Rays, Neutrons, and Light, Proceedings of the 216th National Meeting of the American Chemical Society; Cebe P, Hsaio BS, Lohse DJ, Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, August 21–27, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Azuah RT; Kneller LR; Qiu Y; Tregenna-Piggott PLW; Brown CM; Copley JRD; Dimeo RM DAVE: A Comprehensive Software Suite for the Reduction, Visualization, and Analysis of Low Energy Neutron Spectroscopic Data. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol 2009, 114, 341–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Giannozzi P; Baroni S; Bonini N; Calandra M; Car R; Cavazzoni C; Ceresoli D; Chiarotti GL; Cococcioni M; Dabo I; et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: A Modular and Open-Source Software Project for Quantum Simulations of Materials. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2009, 21, No. 395502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kresse G; Furthmuller J; Hafner J Ab initio Force Constant Approach to Phonon Dispersion Relations of Diamond and Graphite. Europhys. Lett 1995, 32, 729–734. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Yildirim T Structure and Dynamics from Combined Neutron Scattering and First-Principles Studies. Chem. Phys 2000, 261, 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Momma K; Izumi F VESTA 3 for Three-Dimensional Visualization of Crystal, Volumetric and Morphology Data. J. Appl. Crystallogr 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Skripov AV; Soloninin AV; Babanova OA Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies of Atomic Motion in Borohydrides. J. Alloys Compd 2011, 509S, S535–S539. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Abragam A The Principles of Nuclear Magnetism; Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Skripov AV; Soloninin AV; Babanova OA; Hagemann H; Filinchuk Y Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Study of Reorientational Motion in α-Mg(BH4)2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 12370–12374. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Skripov AV; Soloninin AV; Ley MB; Jensen TR; Filinchuk Y Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies of BH4 Reorientations and Li Diffusion in LiLa(BH4)3Cl. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 14965–14972. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Soloninin AV; Babanova OA; Medvedev EY; Skripov AV; Matsuo M; Orimo S Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Study of Atomic Motion in Mixed Borohydride-Amide Na2(BH4)(NH2). J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 14805–14812. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Gradišek A; Jepsen LH; Jensen TR; Conradi MS Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Study of Molecular Dynamics in Ammine Metal Borohydride Sr(BH4)2(NH3)2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 24646–24654. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Shane DT; Rayhel LH; Huang Z; Zhao JC; Tang X; Stavila V; Conradi MS Comprehensive NMR Study of Magnesium Borohydride. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 3172–3177. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Ban V; Soloninin AV; Skripov AV; Hadermann J; Abakumov A; Filinchuk Y Pressure-Collapsed Amorphous Mg-(BH4)2: An Ultradense Complex Hydride Showing a Reversible Transition to the Porous Framework. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 23402–23408. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Skoryunov RV; Soloninin AV; Babanova OA; Skripov AV; Schouwink P;Černý R Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Study of Atomic Motion in Bimetallic Perovskite-Type Borohydrides ACa-(BH4)3 (A = K, Rb, Cs). J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 19689–19696. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Babanova OA; Soloninin AV; Stepanov AP; Skripov AV; Filinchuk Y Structural and Dynamical Properties of NaBH4 and KBH4: NMR and Synchrotron X-ray Diffraction Studies. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 3712–3718. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Skripov AV; Soloninin AV; Babanova OA; Skoryunov RV Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies of Atomic Motion in Borohydride-Based Materials: Fast Anion Reorientations and Cation Diffusion. J. Alloys Compd 2015, 645, S428–S433. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Phua TT; Beaudry BJ; Peterson DT; Torgeson DR; Barnes RG; Belhoul M; Styles GA; Seymour EFW Paramagnetic Impurity Effects in NMR Determinations of Hydrogen Diffusion and Electronic Structure in Metal Hydrides. Gd3+ in YH2 and LaH2.25. Phys. Rev. B 1983, 28, 6227–6250. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Horsewill AJ Quantum tunnelling aspects of methyl group rotation studied by NMR. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc 1999, 35, 359–389. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Haupt J Einfluβ von Quanteneffekten der Methylgruppenrotation auf die Kernrelaxation in Festkörpern. Z. Naturforsch., A 1971, 26, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Müller-Warmuth W; Schüler R; Prager M; Kollmar A Rotational Tunneling in Methylpyridines as Studied by NMR Relaxation and Inelastic Neutron Scattering. J. Chem. Phys 1978, 69, 2382–2392. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Skripov AV; Skoryunov RV; Soloninin AV; Babanova OA; Stavila V; Udovic TJ Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Study of Anion and Cation Reorientational Dynamics in (NH4)2B12H12. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 3256–3262. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Skoryunov RV; Babanova OA; Soloninin AV; Skripov AV; Verdal N; Udovic TJ Effects of Partial Halide Anion Substitution on Reorientational Motion in NaBH4: A Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Study. J. Alloys Compd 2015, 636, 293–297. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Verdal N; Udovic TJ; Rush JJ; Liu X; Majzoub EH; Vajo JJ; Gross AF Dynamical Perturbations of Tetrahydroborate Anions in LiBH4 due to Nanoconfinement in Controlled-pore Carbon Scaffolds. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 17983–17995. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Verdal N; Udovic TJ; Rush JJ; Wu H; Skripov AV Evolution of the Reorientational Motions of the Tetrahydroborate Anions in Hexagonal LiBH4–LiI Solid Solution by High-Q Quasielastic Neutron Scattering. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 12010–12018. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Bee M Quasielastic Neutron Scattering, Principles and Applications in Solid State Chemistry, Biology and Materials Science; Adam Hilger: Bristol, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Hempelmann R Quasielastic Neutron Scattering and Solid State Diffusion; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Verdal N; Udovic TJ; Rush JJ The Nature of BH4− Reorientations in Hexagonal LiBH4. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 1614–1618. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.