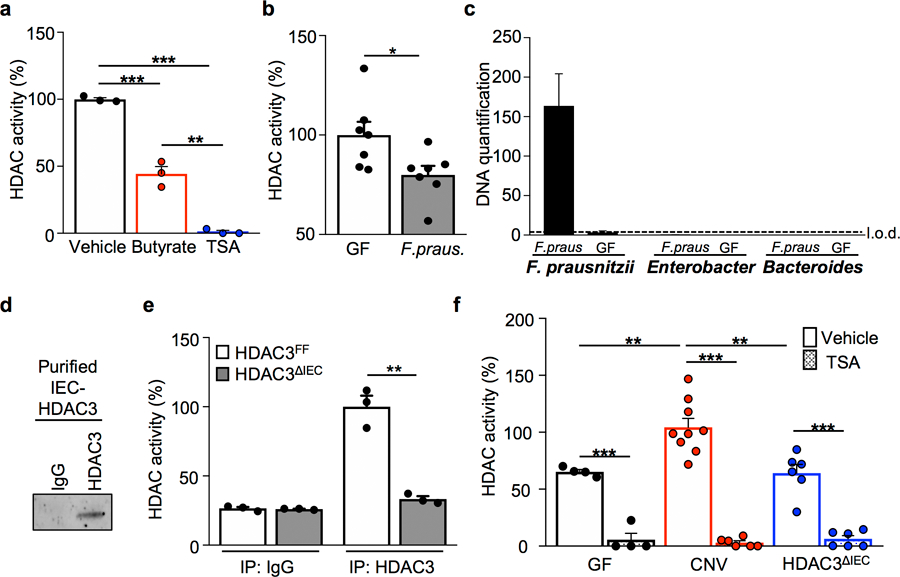

Extended Data Figure 1. Butyrate inhibits epithelial HDAC activity in the intestine.

(a) IEC HDAC activity of large intestine explant treated with vehicle (n=3), 10 mM butyrate (n=3), or 10 mM trichostatin A (TSA; n=3) for 3 hours. ***p=4.16E-07 (Vehicle vs TSA), ***p=0.0006 (Vehicle vs Butyrate), **p=0.0015 (Butyrate vs TSA). (b) IEC HDAC activity of GF mice (n=7) and mice mono-associated with F. prausnitzii (butyrate-producing bacteria) (n=7). *p=0.028. (c) Bacterial-specific qPCR of feces for F. prausnitzii, Enterobacteriaceae, and Bacteroides (n=3/group). (d) Western blot of immunoprecipitated HDAC3 from IECs. For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1. (e) HDAC activity of immunoprecipitated (IP) HDAC3 from HDAC3FF (n=3) and HDAC3ΔIEC (n=3) intestinal epithelium. **p=0.001. (f) HDAC activity of IECs from GF (n=4), CNV (Vehicle n=9, TSA n=6), and HDAC3∆IEC mice (n=6) −/+ 10 μM TSA. ***p=5.77E-05 (GF Vehicle vs TSA), ***p=1.12E-07 (CNV Vehicle vs TSA), ***p=3.49E-05 ( HDAC3∆IEC Vehicle vs TSA), **p= 0.008 (Vehicle GF vs CNV), **p= 0.004 (Vehicle CNV vs HDAC3∆IEC). All graphs are mean of biologic replicates ± s.e.m.; unpaired two-tailed t test. Data were independently repeated three (a-c) or two (d-f) times with similar results. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001