Abstract

Two critical steps in drug development are 1) the discovery of molecules that have the desired effects on a target, and 2) the optimization of such molecules into lead compounds with the required potency and pharmacokinetic properties for translation. DNA-encoded chemical libraries (DECLs) can nowadays yield hits with unprecedented ease, and lead-optimization is becoming the limiting step. Here we integrate DECL screening with structure-based computational methods to streamline the development of lead compounds. The presented workflow consists of enumerating a virtual combinatorial library (VCL) derived from a DECL screening hit and using computational binding prediction to identify molecules with enhanced properties relative to the original DECL hit. As proof-of-concept demonstration, we applied this approach to identify an inhibitor of PARP10 that is more potent and druglike than the original DECL screening hit.

Keywords: DNA-encoded chemical libraries, Computer-guided drug discovery, Poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase, Hit-to-lead development, Virtual combinatorial libraries

Graphical Abstract

ADP-ribosylation is a ubiquitous post-translational protein modification that regulates important cellular processes.1 Poly ADP-ribose polymerases (PARPs) constitute a family of enzymes that form ADP-ribose protein modifications from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) substrates.2 PARP-modulating pharmaceuticals are of high medical importance, and four inhibitors of PARP1 are in clinical use.3, 4 The majority of PARPs are mono (ADP-ribose) transferases,5 and both their cellular roles and medicinal chemistry are less well understood than that of the bona fide PARP polymerases.3, 4 PARP10 is an example of a mono-ADP ribose transferase that regulates important cellular processes.6 PARP10 is involved in immune signaling,7 regulation of metabolism,8 response to DNA-damage,9 and transcriptional regulation.10 The development of chemical probes to study the biological functions of PARP10 is therefore an active research area,11–14 and there is a need to further elucidate its medicinal chemistry and to develop chemical probes with more favorable properties.

As part of our research to establish focused DNA-encoded chemical libraries (DECLs) for drug development, we discovered micromolar inhibitors of PARP10.15 The most prominent PARP10 hit series that emerged from this study contained a 6-carboxy tetralone fragment connected to aromatic heterocycles or phenyl groups via a 2,3-diaminopropionyl methylcarboxamide (MeNHDAP) linker. The MeNH-DAP linker is a remnant of the DECL designed to target NAD+-binding proteins (NADEL; NAD+-mimicking DNA-encoded library), which consists of two carboxylic acid groups assembled on the conserved DAP scaffold (the structure of NADEL is shown in Fig. 2).15 While the diverse carboxylic acids contained in NADEL efficiently map out parts of the NAD+-binding sites, the conserved MeNH-DAP linker samples the protein surface between these fragment-binding pockets suboptimally. Replacing the MeNH-DAP moiety may provide additional binding energy. Furthermore, the MeNH-DAP linker negatively affects the compounds physicochemical properties by contributing a large topological polar surface area (TPSA = 87.3 Å2), as well as several hydrogen bond donors (n = 3) and acceptors (n = 6). The MeNH-DAP group also has four rotatable bonds. Replacing the MeNH-DAP moiety emerges therefore as a priority towards developing NADEL hits for PARP10 and other targets into lead molecules.

Figure 2.

Design of the virtual combinatorial library (PARP10-VCL) used to replace the MeNH-DAP substructure (highlighted in red) of the PARP10 DECL screening hit A82-(CONHMe)-B354. The PARP10-VCL compounds consist of 350 diamines onto which ten tetralones and three 2-quinoxalinols were assembled, providing a virtual library with 10500 distinct structures for docking-based screening.

The encountered situation is representative for DECL-screening hits in general. DECLs allow screening vast compound libraries rapidly and economically16–20 and have provided clinical lead compounds.21–23 The combinatorial nature of DECLs and the need to attach molecules to DNA codes leads to libraries of compounds for which most of the structural diversity is concentrated in some parts of the molecules (often capping fragments such as carboxylic acids or amines) whereas other parts of the molecule (e.g. scaffolds) have lower structural diversity.24 Extensive research efforts have been dedicated to alleviate this problem by developing new DNA-compatible chemistry,25 constructing DECLs with variable scaffolds,26–28 natural product derived DECLs,29–31 and building libraries in which different reactions are performed during a synthesis cycle.32, 33 We aim to address the challenge of low-diversity substructures at the level of hit-to-lead development instead of during DECL construction. To date, only few studies have explored how to take advantage of the unique combinatorial characteristics of DECLs24 to facilitate lead development. In one report, McCloskey et al. combined DECL-screening data with machine learning to discover compounds with improved potency and properties.34 In another approach, Wellaway et al. merged DECL hits with fragment-based screening.35 Here we present a method that integrates DECL screening with structure-based computational drug development methods. In the outlined strategy, virtual combinatorial libraries (VCLs) are designed based on the structure of a DECL screening hit; moieties that are highly diverse in the DECL are kept constant in these VCLs, and parts that have low structural diversity in the underlying DECL are varied (Fig. 1). To evaluate this concept, we used one of the PARP10 screening hits discovered from NADEL15 and replaced the unfavorable MeNH-DAP moiety by alternative linkers.

Figure 1.

Pursued approach of integrating DNA-encoded chemical library (DECL) screens with structure-based computational drug discovery methods. A DECL screen provides candidate hit molecules that consist of structural elements that have been effectively selected with regard to the target, but also moieties that had low diversity in the DECL. A virtual combinatorial library (VCL) is constructed from a screening hit keeping some substructures constant and varying others. In silico screening identifies molecules in the VCL that are likely to bind the protein with high affinity and have more favorable physicochemical properties. Selected hits are synthesized and tested to identify compounds with enhanced properties for further lead development.

The starting point to explore the proposed approach of integrating DECL screens and computational drug discovery was the PARP10 inhibitor A82-(CONHMe)-B354 (Fig. 2). This compound inhibited PARP10 in a histone ADP-ribosylation assay with IC50 = 6.0 μM and showed selectivity over other PARPs tested.15 A82-(CONHMe)-B354 has liabilities with regard to chemical features that are used to predict favorable ADME properties and druglikeness such as a problematically high topological polar surface area (TPSA) of 145.8 Å2. The objective of the study was to replace the MeNH-DAP group by a linker to reduce the polar surface area and to improve the overall properties of the compound while maintaining or enhancing the potency of PARP10 inhibition.

The first step of the study involved the assembly of a VCL based on the structure of A82-(CONHMe)-B354 (PARP10-VCL; Fig. 2). The tetralone and 2-quinoxalinol fragments of A82-(CONHMe)-B354 were kept constant in PARP10-VCL because they are the result of sampling during the DECL screen, whereas the connectivity of the two fragments was varied. 350 different diamine scaffolds were selected based on commercial accessibility and favorable structural features. As the linkers changed, it was possible that the ideal site of attachment of the fragments to the linkers differs from the carboxylic acids in NADEL. We therefore included ten tetralone derivatives with different positions of the amine-reactive group and three different 2-quinoxalinol moieties. In addition to carboxylic acids, the tetralone fragments used for VCL construction also contained isocyanates to form ureas, sulfonyl chlorides to form sulfonamides, and halogenated derivatives for nucleophilic aromatic substitution. The Pipeline Pilot software (3dsbiovia.com) was used to enumerate the 10500 PARP10-VCL compounds.

PARP1-VCL was screened in silico by means of the Glide docking algorithm36 to identify compounds that fit into the PARP10 binding pocket. A crystal structure of PARP10 in complex with a small molecule inhibitor (PDB 5LX6)37 was used as the target. Top 1% of Glide hits were rescored using Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA) method.38 The rescored hit list was visually inspected from the top based on qualitative criteria, such as exposure to solvent or entropic penalty upon binding, to select hits for synthesis. We also paid attention to structural diversity of the selected hits, including fragments with different attachment chemistry and connection geometry and a broad range of diamine linkers, as well as their synthetic feasibility. Table 1 shows the structures of the ten selected compounds and the docking pose of hit compound 5a is shown in Figure 3.

Table 1.

Predicted PARP10 inhibitors identified from screening PARP10-VCL.

| Compounda | Structure | Glide Score | PARP10 1 μM |

10 μM | PARP14 1 μM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5a | −12.20 | 25 | 90 | 21 | |

| 5b | −12.07 | 15 | 9 | 12 | |

| 5c | −11.86 | 13 | 10 | 2 | |

| 9b |  |

−11.70 | 13 | 4 | 0 |

| 14 | −11.65 | 17 | 46 | 0 | |

| 5f | −11.63 | 1 | 15 | 17 | |

| 5d | −11.57 | 11 | 16 | 27 | |

| 9a |  |

−11.57 | 13 | 12 | 7 |

| 9c | −11.51 | 0 | 37 | 0 (5b) | |

| 5e | −11.49 | 0 | 35 | 6 (10b) |

Compounds were sorted by Glide Scores and numbered according to synthetic method (see Scheme 1). Predicted physicochemical properties of compounds are summarized in Table S1 in the Supporting Information.

Inhibition at a compound concentration of c = 10 μM.

Figure 3.

Docking pose of the predicted PARP10 inhibitor 5a binding to PARP10 (crystal structure PDX 5LX6).

The synthesis of the ten selected compounds is shown in Scheme 1. Compounds 5a-f were synthesized as outlined in Scheme 1a. The tetralone carboxylic acids 1a-c, were coupled with the Boc-protected diamines 2a-e using standard HATU or EDC coupling conditions in good yields. The deprotection of the resulting amides 3a-e was accomplished using TFA followed by coupling with the quinoxaline propanoic acid 4 to afford the final compounds 5a-e. In a similar manner compound 5f was synthesized by switching the order of the two coupling reactions.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of PARP10 inhibitor candidates. Reagents and conditions: (a) EDC or HATU, DMF, DIEA, 40–48%; (b) 1. TFA, DCM, quant. 2. EDC or HATU, DIEA, DMF, 13–33%. (c) DCM, DIEA, 40%.

Compounds 9a-c were synthesized according to Scheme 1b. The tetralone carboxylic acids 7a,b were coupled with the Boc-protected diamines 2e,g-h to afford the intermediate amides 8a-c. Deprotection of the Boc group followed by coupling with carboxylic acid 4 afforded the final compounds 9a-c.

The urea derivative 14 was synthesized as outlined in Scheme 1c. The amino tetralone 10 reacted with the Boc-piperazine carbamoyl chloride 11 to afford compound 12 in 40% yield. Deprotection followed by coupling with carboxylic acid 13 afforded the final compound 14 in 34% yield.

The inhibitory potency of the synthesized compounds towards PARP10 was evaluated in an ADP-ribosyltransferase assay (BPS Bioscience) at concentrations of 1 μM and 10 μM (Table 1). Inhibition of PARP14 was measured as control because PARP10 and PARP14 are structurally similar. Compound 5a with the lowest Glide score (−12.20) distinctly inhibited PARP10 (25 % at 1 μM and 90 % at 10 μM; Table 1). Compound 5a also inhibited PARP14 with similar potency (27% at 1 μM). Inhibition of PARP10 was <50% for the other tested compounds at 10 μM, indicating that their inhibitory potency is at least 2-fold lower than that of the original starting compound A82-(CONHMe)-B354 (IC50 = 6.0 μM). Of these compounds, 14 (46% inhibition), 9c (37% inhibition), and 5f (35% inhibition) showed the most promise and selectivity over PARP14 was observed (Table 1). Even though the VCL-protocol did not enhance the potency of these compounds, they still may serve as starting point for future hit-to-lead efforts given that the MeNH-DAP moiety was replaced by more favorable structures.

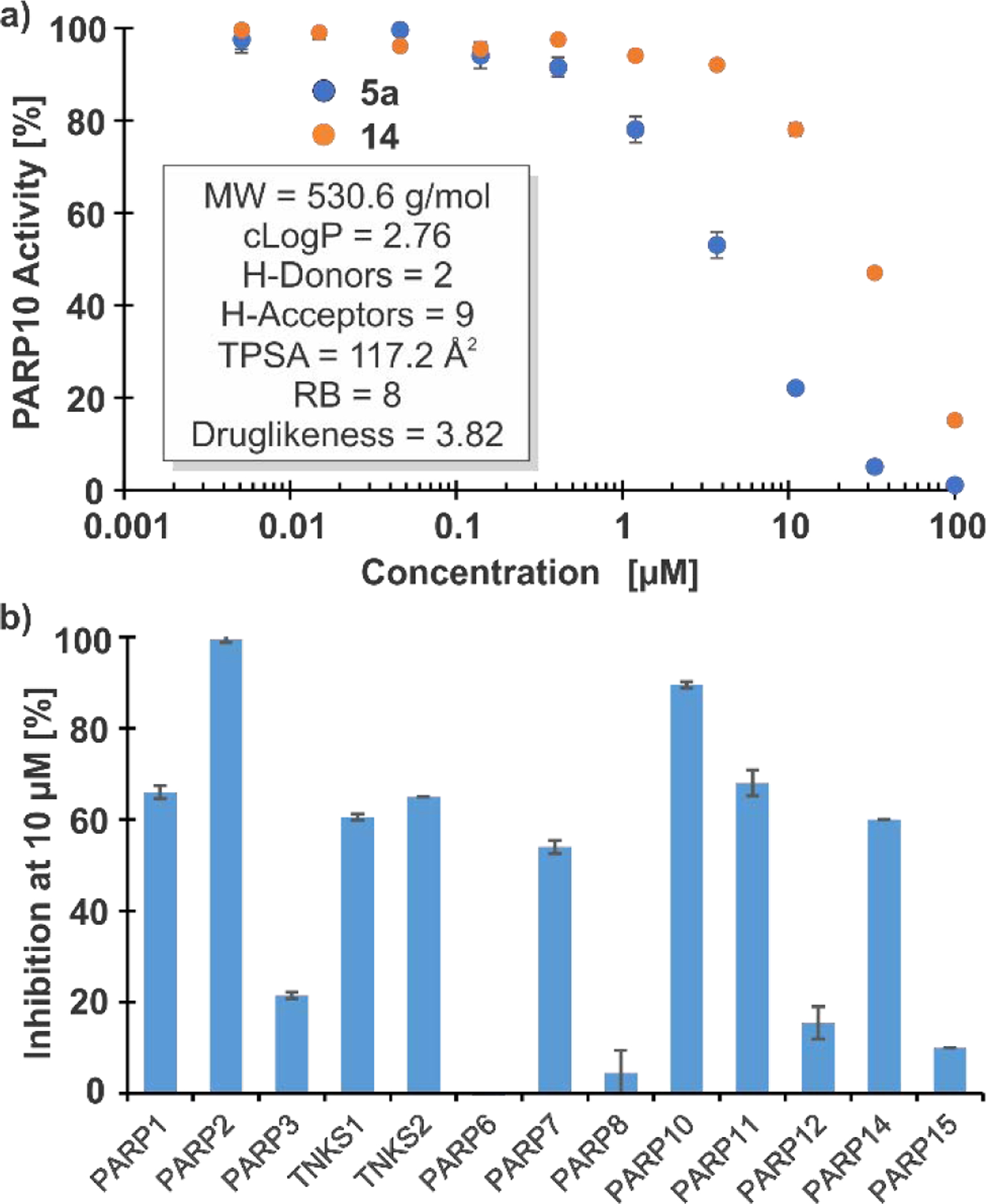

The concentration-dependent inhibition of PARP10 was measured to determine the IC50 values of 5a and 14 (Fig. 4a). Compound 5a inhibited PARP10 with an IC50 value of 3.9 μM. Replacing the MeNH-DAP linker by a 4-aminomethyl-4-methylpiperidine linker therefore improved the inhibitory potency by 1.5-fold. Importantly, the topological polar surface area decreased to 117.1 Å2 from 145.8 Å2, and the druglikeness score (calculated by the algorithm integrated in DataWarrior) increased to 3.82 from 2.22. Therefore, 5a offers a superior starting point for lead development relative to A82-(CONHMe)-B354. Compound 14 inhibited PARP10 with an IC50 value of ~28 μM. Testing the inhibition of 12 other PARPs provided a selectivity profile of 5a (Fig. 4b). While 5a exhibited high selectivity towards some PARPs (Inhibition at 10 μM: PARP3 = 22%; PARP6 = 0 %; PARP8 = 5%; PARP12 = 16%: PARP15 = 10%), this compound inhibited the activity of the other PARPs by >50% at 10 μM and completely blocked the activity of PARP2. In contrast, the initial DECL-screening hit A82-(CONHMe)-B354 exhibited satisfactory target selectivity, and inhibition of other PARPs at 10 μM was below 25%.15

Figure 4.

Inhibitory activity of VCL-derived molecules. a) Dose-response curve of PARP10 inhibition by compounds 5a and 14. Inset: Structural properties of 5a (MW: molecular weight; TPSA: topological polar surface area; RB: rotatable bonds; structural properties of 14 are provided in Table S1 in the Supporting Information). b) Selectivity profile of 5a to PARP enzymes.

In summary, this report introduces an innovative approach to develop early lead compounds from DECL hits by in silico screening of a VCL. The study validated the concept by identifying a PARP10 inhibitor that differs from the DECL screening hit by the structure of the scaffold and the linkage geometry on the tetralone. Overall, the modification yielded a favorable decrease in polar surface area, increased druglikeness, and modestly enhanced potency. Having established the conceptual framework of the approach, the next step will be to gain further understanding on how to design VCLs and enhance the predictability of the in silico screen. It is noteworthy that the original DECL screening hit A82-(CONHMe)-B354 had higher potency than most of the tested virtual screening hits. While this result suggests that further improvements of the workflow are needed, it also bears testimony to the effectiveness of DECLs to intimately sample protein binding sites. The MeNH-DAP moiety evidently provides critical interactions to the affinity of A82-(CONHMe)-B354 to PARP10. This outcome is in line with previous studies that demonstrated that even subtle linker modifications of DECL hits often have a profound effect on compound potency.26 Likewise, the higher target selectivity of A82-(CONHMe)-B354 compared to 5a emphasize the unique ability of DECLs to address target selectivity in early design stages.39 In conclusion, integrating DECL-screens with computer-guided drug discovery emerges as an attractive strategy to rapidly access lead compounds with high potency and favorable characteristics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

R.M.F. acknowledges start-up funds supported by the University of Utah, the Huntsman Cancer Institute, and the Utah Science Technology and Research Initiative. D.V.F acknowledges the McDaniel College Summer research fund, Jean Richards Endowment, Scott Dahne summer research fund and Schofield Chemistry fund for support. This work was supported by the University Cancer Research Fund (UCRF), an award RX03712105 from the Eshelman Institute for Innovation, and by the National Institutes of Health (Grants R01GM132299).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary Material

Supplementary material to this article can be found online at TBD.

References and notes

- 1.Cohen MS; Chang P, Insights into the biogenesis, function, and regulation of ADP-ribosylation. Nat. Chem. Biol 2018, 14, 236–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bai P, Biology of Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerases: The Factotums of Cell Maintenance. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 947–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Min A; Im SA, PARP Inhibitors as Therapeutics: Beyond Modulation of PARylation. Cancers 2020, 12, in press (doi: 10.3390/cancers12020394). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vyas S; Chang P, New PARP targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2014, 14 (7), 502–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vyas S; Matic I; Uchima L; Rood J; Zaja R; Hay RT; Ahel I; Chang P, Family-wide analysis of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity. Nat. Commun 2014, 5, 4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufmann M; Feijs KL; Luscher B, Function and regulation of the mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase ARTD10. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol 2015, 384, 167–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verheugd P; Forst AH; Milke L; Herzog N; Feijs KL; Kremmer E; Kleine H; Luscher B, Regulation of NF-kappaB signalling by the mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase ARTD10. Nat. Commun 2013, 4, 1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marton J; Fodor T; Nagy L; Vida A; Kis G; Brunyanszki A; Antal M; Luscher B; Bai P, PARP10 (ARTD10) modulates mitochondrial function. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0187789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicolae CM; Aho ER; Vlahos AH; Choe KN; De S; Karras GI; Moldovan GL, The ADP-ribosyltransferase PARP10/ARTD10 interacts with proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and is required for DNA damage tolerance. J. Biol. Chem 2014, 289, 13627–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu M; Schreek S; Cerni C; Schamberger C; Lesniewicz K; Poreba E; Vervoorts J; Walsemann G; Grotzinger J; Kremmer E; Mehraein Y; Mertsching J; Kraft R; Austen M; Luscher-Firzlaff J; Luscher B, PARP-10, a novel Myc-interacting protein with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity, inhibits transformation. Oncogene 2005, 24, 1982–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgan RK; Kirby IT; Vermehren-Schmaedick A; Rodriguez K; Cohen MS, Rational Design of Cell-Active Inhibitors of PARP10. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2019, 10, 74–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holechek J; Lease R; Thorsell AG; Karlberg T; McCadden C; Grant R; Keen A; Callahan E; Schuler H; Ferraris D, Design, synthesis and evaluation of potent and selective inhibitors of mono-(ADP-ribosyl)transferases PARP10 and PARP14. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2018, 28, 2050–2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murthy S; Desantis J; Verheugd P; Maksimainen MM; Venkannagari H; Massari S; Ashok Y; Obaji E; Nkizinkinko Y; Luscher B; Tabarrini O; Lehtio L, 4-(Phenoxy) and 4-(benzyloxy)benzamides as potent and selective inhibitors of mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase PARP10/ARTD10. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2018, 156, 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venkannagari H; Verheugd P; Koivunen J; Haikarainen T; Obaji E; Ashok Y; Narwal M; Pihlajaniemi T; Luscher B; Lehtio L, Small-Molecule Chemical Probe Rescues Cells from Mono-ADP-Ribosyltransferase ARTD10/PARP10-Induced Apoptosis and Sensitizes Cancer Cells to DNA Damage. Cell. Chem. Biol 2016, 23, 1251–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuen LH; Dana S; Liu Y; Bloom SI; Thorsell AG; Neri D; Donato AJ; Kireev D; Schuler H; Franzini RM, A Focused DNA-Encoded Chemical Library for the Discovery of Inhibitors of NAD(+)-Dependent Enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 5169–5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franzini RM; Neri D; Scheuermann J, DNA-encoded chemical libraries: advancing beyond conventional small-molecule libraries. Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 1247–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodnow RA Jr.; Dumelin CE; Keefe AD, DNA-encoded chemistry: enabling the deeper sampling of chemical space. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2017, 16, 131–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neri D; Lerner RA, DNA-Encoded Chemical Libraries: A Selection System Based on Endowing Organic Compounds with Amplifiable Information. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2018, 87, 479–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salamon H; Klika Skopic M; Jung K; Bugain O; Brunschweiger A, Chemical Biology Probes from Advanced DNA-encoded Libraries. ACS Chem. Biol 2016, 11, 296–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zambaldo C; Barluenga S; Winssinger N, PNA-encoded chemical libraries. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2015, 26, 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuozzo JW; Clark MA; Keefe AD; Kohlmann A; Mulvihill M; Ni H; Renzetti LM; Resnicow DI; Ruebsam F; Sigel EA; Thomson HA; Wang C; Xie Z; Zhang Y, Novel Autotaxin Inhibitor for the Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Clinical Candidate Discovered Using DNA-Encoded Chemistry. J Med Chem 2020. in press, ( 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00688). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris PA; King BW; Bandyopadhyay D; Berger SB; Campobasso N; Capriotti CA; Cox JA; Dare L; Dong X; Finger JN; Grady LC; Hoffman SJ; Jeong JU; Kang J; Kasparcova V; Lakdawala AS; Lehr R; McNulty DE; Nagilla R; Ouellette MT; Pao CS; Rendina AR; Schaeffer MC; Summerfield JD; Swift BA; Totoritis RD; Ward P; Zhang A; Zhang D; Marquis RW; Bertin J; Gough PJ, DNA-Encoded Library Screening Identifies Benzo[b][1,4]oxazepin-4-ones as Highly Potent and Monoselective Receptor Interacting Protein 1 Kinase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 2163–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Podolin PL; Bolognese BJ; Foley JF; Long E 3rd; Peck B; Umbrecht S; Zhang X; Zhu P; Schwartz B; Xie W; Quinn C; Qi H; Sweitzer S; Chen S; Galop M; Ding Y; Belyanskaya SL; Israel DI; Morgan BA; Behm DJ; Marino JP Jr.; Kurali E; Barnette MS; Mayer RJ; Booth-Genthe CL; Callahan JF, In vitro and in vivo characterization of a novel soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2013, 104–105, 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franzini RM; Randolph C, Chemical Space of DNA-Encoded Libraries. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 6629–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gotte K; Chines S; Brunschweiger A, Reaction Development for DNA-Encoded Library Technology: From Evolution to Revolution? Tetrahedron Lett. 2020, 61, 151889. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Favalli N; Biendl S; Hartmann M; Piazzi J; Sladojevich F; Graslund S; Brown PJ; Nareoja K; Schuler H; Scheuermann J; Franzini R; Neri D, A DNA-Encoded Library of Chemical Compounds Based on Common Scaffolding Structures Reveals the Impact of Ligand Geometry on Protein Recognition. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 1303–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerry CJ; Wawer MJ; Clemons PA; Schreiber SL, DNA Barcoding a Complete Matrix of Stereoisomeric Small Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 10225–10235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng H; Zhou J; Sundersingh FS; Summerfield J; Somers D; Messer JA; Satz AL; Ancellin N; Arico-Muendel CC; Sargent Bedard KL; Beljean A; Belyanskaya SL; Bingham R; Smith SE; Boursier E; Carter P; Centrella PA; Clark MA; Chung CW; Davie CP; Delorey JL; Ding Y; Franklin GJ; Grady LC; Herry K; Hobbs C; Kollmann CS; Morgan BA; Pothier Kaushansky LJ; Zhou Q, Discovery SAR, and X-ray Binding Mode Study of BCATm Inhibitors from a Novel DNA-Encoded Library. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2015, 6, 919–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma P; Xu H; Li J; Lu F; Ma F; Wang S; Xiong H; Wang W; Buratto D; Zonta F; Wang N; Liu K; Hua T; Liu ZJ; Yang G; Lerner RA, Functionality-Independent DNA Encoding of Complex Natural Products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2019, 58, 9254–9261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J; Li Y; Lu F; Liu L; Ji Q; Song K; Yin Q; Lerner RA; Yang G; Xu H; Ma P, A DNA-encoded library for the identification of natural product binders that modulate poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1, a validated anti-cancer target. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2020, in press, ( 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.04.022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie J; Wang S; Ma P; Ma F; Li J; Wang W; Lu F; Xiong H; Gu Y; Zhang S; Xu H; Yang G; Lerner RA, Selection of Small Molecules that Bind to and Activate the Insulin Receptor from a DNA-Encoded Library of Natural Products. iScience 2020, 23, 101197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paciaroni NG; Ndungu JM; Kodadek T, Solid-phase synthesis of DNA-encoded libraries via an “aldehyde explosion” strategy. Chem. Commun 2020, 56, 4656–4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark MA; Acharya RA; Arico-Muendel CC; Belyanskaya SL; Benjamin DR; Carlson NR; Centrella PA; Chiu CH; Creaser SP; Cuozzo JW; Davie CP; Ding Y; Franklin GJ; Franzen KD; Gefter ML; Hale SP; Hansen NJ; Israel DI; Jiang J; Kavarana MJ; Kelley MS; Kollmann CS; Li F; Lind K; Mataruse S; Medeiros PF; Messer JA; Myers P; O’Keefe H; Oliff MC; Rise CE; Satz AL; Skinner SR; Svendsen JL; Tang L; van Vloten K; Wagner RW; Yao G; Zhao B; Morgan BA, Design, synthesis and selection of DNA-encoded small-molecule libraries. Nat. Chem. Biol 2009, 5, 647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCloskey K; Sigel EA; Kearnes S; Xue L; Tian X; Moccia D; Gikunju D; Bazzaz S; Chan B; Clark MA; Cuozzo JW; Guie MA; Guilinger JP; Huguet C; Hupp CD; Keefe AD; Mulhern CJ; Zhang Y; Riley P, Machine Learning on DNA-Encoded Libraries: A New Paradigm for Hit Finding. J. Med. Chem 2020, in press, ( 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00452). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wellaway CR; Amans D; Bamborough P; Barnett H; Bit RA; Brown JA; Carlson NR; Chung CW; Cooper AWJ; Craggs PD; Davis RP; Dean TW; Evans JP; Gordon L; Harada IL; Hirst DJ; Humphreys PG; Jones KL; Lewis AJ; Lindon MJ; Lugo D; Mahmood M; McCleary S; Medeiros P; Mitchell DJ; O’Sullivan M; Le Gall A; Patel VK; Patten C; Poole DL; Shah RR; Smith JE; Stafford KAJ; Thomas PJ; Vimal M; Wall ID; Watson RJ; Wellaway N; Yao G; Prinjha RK, Discovery of a Bromodomain and Extraterminal Inhibitor with a Low Predicted Human Dose through Synergistic Use of Encoded Library Technology and Fragment Screening. J. Med. Chem 2020, 63, 714–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friesner RA; Banks JL; Murphy RB; Halgren TA; Klicic JJ; Mainz DT; Repasky MP; Knoll EH; Shelley M; Perry JK; Shaw DE; Francis P; Shenkin PS, Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem 2004, 47, 1739–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thorsell AG; Ekblad T; Karlberg T; Low M; Pinto AF; Tresaugues L; Moche M; Cohen MS; Schuler H, Structural Basis for Potency and Promiscuity in Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase (PARP) and Tankyrase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 1262–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rastelli G; Del Rio A; Degliesposti G; Sgobba M, Fast and accurate predictions of binding free energies using MM-PBSA and MM-GBSA. J. Comput. Chem 2010, 31, 797–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franzini RM; Nauer A; Scheuermann J; Neri D, Interrogating target-specificity by parallel screening of a DNA-encoded chemical library against closely related proteins. Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 8014–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.