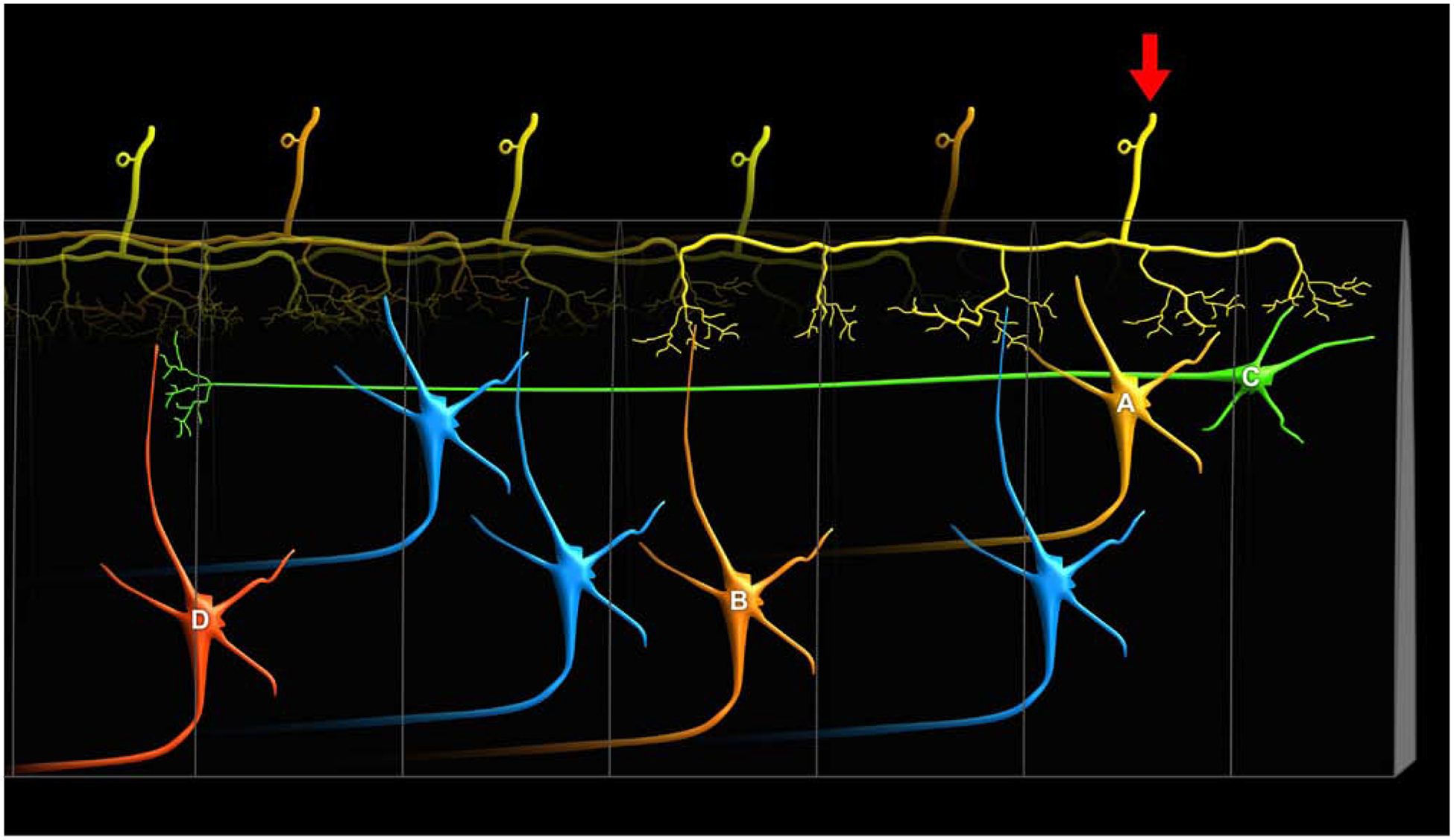

Figure 4. Schematic Illustration of Anatomic Substrates Supporting Spinal Distribution of Nociceptive Input.

There are several anatomical pathways that can support the substantial rostro-caudal distribution of nociceptive activity within the spinal cord. First, when both A-delta and C-fiber afferents enter the spinal cord, they branch considerably in the rostro-caudal direction and traverse relatively long distances within Lissauer’s tract prior to entering the dorsal horn [84–86]. These distances are sufficiently large to extend 3 to 7 spinal cord segments (yellow primary afferent denoted by arrow). Accordingly, they can activate ascending neurons within the segment in which they enter (yellow neuron A), as well as neurons several segments rostral or caudal to the segment of entry (orange neuron B). Second, there are substantial propriospinal interconnections that may be sufficient to transmit nociceptive information even further along the rostral-caudal axis of the spinal cord [87, 88], as well as across the midline to the contralateral dorsal horn [89]. These neurons have cell bodies that reside in laminae I, V and VII, and can project more than eight spinal segments (green neuron C). Moreover, they can be activated by noxious stimuli [88]. While typically thought about in the context of motor control, specifically coordinating forelimb with hindlimb activity, they may also provide a substrate for wide ranging facilitation or inhibition of neurons across many spinal segments (red neuron D) [87]. For example, stimuli applied to sites as remote as the forelimb and face can inhibit the responses of noxious stimuli applied to the hindlimb of spinal cord transected monkeys [90]. This integration of sensory input over vast portions of the spinal cord cannot be explained simply by the branching of primary afferents, suggesting that proprio-spinal interconnections are critically involved. Thus, spinal distribution of nociceptive input and potential neuron recruitment may be driven by both widely branching primary afferents as well as by propriospinal interconnections. In addition, this widespread distribution of nociceptive information is key for multi-segmental spatial summation of pain [25].