Highlights

-

•

Compared with matched normative data, impaired cognitive function was substantial.

-

•

Several correlations between radiation dose and cognitive impairment were present.

-

•

Radiation-induced white matter hyperintensities were present in 2/27 participants.

-

•

One participant displayed radiation-induced necrosis in the temporal lobe.

-

•

The domains affecting quality of life the most were fatigue and quality of sleep.

Keywords: Sinonasal cancer, Radiotherapy, Late toxicity, MRI, Cognitive function, Quality of life

Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the study was to evaluate neurocognitive late effects, structural alterations and associations between cognitive impairment and radiation doses as well as cerebral tissue damage after radiotherapy for sinonasal cancer. Furthermore, the aim was to report quality of life (QoL) and self-reported cognitive capacity.

Materials and methods

Recurrence-free patients previously treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy with a curative intent were eligible for the study. Study examinations comprised comprehensive neurocognitive testing, MRI of the brain, and self-reported outcomes.

Results

A total of 27 patients were included. Median age was 67 years (range 47–83). The majority of test outcomes were below normative values in any degree, and 37% of the participants had clinically significant neurocognitive impairment when compared with normative data. Correlations between absorbed doses to specific substructures of the brain and neurocognitive outcomes were present for Wechsler’s Adult Intelligence Scale-digit span and Controlled Oral Word Association Test-S. Structural MRI revealed macroscopic abnormalities in three patients; infarction (n = 1), diffuse white matter intensities (n = 2) and necrosis (n = 1). In the analysis of atrophy of cerebral tissue, no correlations were present with neither radiation dose to cerebral substructures nor neurocognitive impairment. The global QoL of the cohort was 75. The most affected outcomes were ‘fatigue’, ‘insomnia’, and ‘drowsiness’. A total of 59% of participants reported significantly impaired quality of sleep. Self-reported cognitive function revealed that ‘memory’ was the most affected cognitive domain. For the domains of ‘memory’ and ‘language’, self-reported functioning was associated with objectively measured neurocognitive outcomes.

Conclusion

Cerebral toxicity after radiotherapy for sinonasal cancer was substantial. Clinically significant cognitive impairment was present in more than one third of the participants, and several dose–response associations were present. Furthermore, the presence of macroscopic radiation sequelae indicated considerable impact of radiotherapy on brain tissue.

1. Introduction

Sinonasal tumours are rare entities derived from the epithelium of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Most often, the curatively intended treatment of sinonasal cancer (SNC) comprises a combination of radiation and surgery [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. The location of the tumours poses a challenge in radiotherapy, as the delivery of sufficient radiation dose to the target is difficult while sparing healthy organs adjacent to the tumours. The focus of treatment optimisation has traditionally been sparing the optic pathways and the pituitary gland, as radiation dose to these structures carries a risk of severe and permanent late toxicity with subsequent great impact on the patients’ quality of life (QoL) [6], [7], [8], [9]. The urge to reduce dose to ocular structures and the pituitary gland may have resulted in increased volumes of irradiated brain tissue.

Cerebral irradiation may cause decline in cognitive function, as described in cohorts of patients receiving radiotherapy for intracranial tumours [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18] and whole brain irradiation [19], [20], [21]. Different domains of cognitive functions are potentially affected, namely processing speed, attention, working memory, learning and memory, verbal fluency and executive function. As for radiation-induced cerebral tissue damage, both diffuse white matter hyperintesities, radiation necrosis, atrophy, vascular damage, and microscopic tissue damage might appear. Functional and structural radiation-related changes after treatment of SNC are sparsely described in the literature, and to the best of our knowledge, no dose–response analyses have been published.

Patients with SNC are relevant for studies of functional and structural changes induced by irradiation, as the cerebral tissue is not directly affected by tumour growth or intracranial surgery. Evidence of dose–response correlations have been published for patients with primary brain tumours by Gondi et al. [22], presenting a Normal Tissue Complication Probability (NTCP) model for the prediction of cognitive decline. In order to prioritise the dose distribution to organs at risk, including the brain, NTCP models for SNC and data concerning radiation-induced effects on the brain are needed, but not yet available. Studies focusing on cerebral late toxicity after radiothereapy for SNC are sparse, despite their importance of future patient selection of different treatment modalities for SNC (primarily proton vs. photon therapy) and the dosimetric priorities of the brain for intensity-modulated radiotherapy.

The aim of the present study was to investigate neurocognitive toxicity and MRI changes of the brain after radiotherapy for SNC and QoL. The study includes an evaluation of associations between radiation doses, neurocognitive functioning and cerebral tissue damage.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

A cross-sectional design was applied and carried out in two Danish oncology centres. Eligible patients were diagnosed with cancer of the nasal cavity or maxillary, sphenoid, ethmoid, or frontal sinus in January 2008 through December 2016. Participants underwent curatively intended primary or postoperative radiotherapy. Exclusion criteria were age below 18, histology showing malignant melanoma, sarcoma or lymphoma, tumour location in the nasal vestibule, treatment with a palliative intent, recurrent disease, mental illness, or lacking ability to speak or understand Danish.

2.2. Examinations

Study examinations comprised neurocognitive testing, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and QoL questionnaires. The examinations were performed at the local oncology centre during one or two visits within one month. Patient visits occurred during May-August 2018 in centre 1 and during August-September 2019 in centre 2.

2.2.1. Neurocognitive testing

All participants underwent testing with a battery of ten standardised neurocognitive tests covering different domains of cognitive function. The battery included:

-

-

Trail Making Test (TMT) Part A and B [23]: Part A was used to assess processing speed, while part B assessed executive functioning.

-

-

Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT) [24] was used to assess participants’ sustained attention.

-

-

Wechsler’s Adult Intelligence Scale IV (WAIS-IV) [25]. The sub-test Coding was used to assess processing speed and the sub-test Digit Span assessed working memory. WAIS-Information is a standardised test of common knowledge providing a good estimate of participants’ premorbid cognitive capacity.

-

-

Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised (HVLT-R) [26] The total score was used to assess participants’ verbal learning ability and the delayed score assessed verbal recall.

-

-

Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) (Animal and S) [27] was used to assess phonetic and semantic word fluency.

-

-

Stroop Color Word Test [28] was used to assess participants’ executive functioning.

When different tests measured the function of one domain (e.g. TMT-B and Stroop Color Word assessing executive function), they adressed specific aspects of that domain, and they were weighted equally in the analysis. For each test outcome, Z-scores were calculated using normative data adjusted for age and, when available, education level, reflecting deviations from the expected normative values. A global score was calculated, defined as the mean of Z-scores from all tests, except WAIS information, which was included as a measure of premorbid cognitive capacity. A Z-score < −1.5 in any test outcome was defined as a significantly impaired score in that outcome [29], and participants with Z-scores < −1.5 in two different outcomes were considered as having clinically significant cognitive impairment [29]. Neurocognitive tests were administered by the primary investigator, who previously to testing underwent thorough education, and initially performed the tests under the guidance and supervision of an experienced neuropsychologist in the field. Continous supervision was available at all times. Each test sessions lasted approximately 50 min.

2.2.2. Cerebral MRI

All MRIs were included in the imaging analysis, except for analyses of atrophy, where only MRIs from centre 1 were included, due to hardware differences. All MRIs were performed by experienced radiographers. The scanners used in the study were Siemens Magnetom Prisma 3 T (centre 1) and Phillips Ingenia 1.5 T (centre 2). T2-weighted fluid attenuated inversion recovery (T2FLAIR), and T1-weighted (T1w) MRI sequences were acquired, no contrast enhancement was used. Macroscopic structural damage to cerebral tissue was assessed by an experienced neuro-radiologist using T2FLAIR. The areas were subsequently delineated. Volumetry of substructures was automatically calculated using T1w images and the framework described in Aubert-Broche et al. [30]. In this framework, images are normalized and registered to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space, a coordinate system used to describe cerebral locations. Subsequently, brain tissue is segmented into white matter, gray matter and cerebrospinal fluid and merged with an atlas [31] in MNI space to obtain delineations of cortical and subcortical regions. Hippocampus, thalamus were separately delineated using patch-based label fusion [32]. Following delineation, T1w images were co-registered by rigid registration [33] to the planning computed tomography image and corresponding radiation treatment plan, and radiation doses to cerebral substructures were subsequently read in the dose volume histograms.

2.2.3. QoL

All participants were asked to complete questionnaires concerning their QoL in general, symptoms of anxiety and depression, sleep quality, and self-perceived cognitive functioning. In addition, demographic data, covering marital status, income, education and use of drugs was included. EORTC-QLQ-C30 (C30) [34] covers specific functional domains as well as various symptoms in scores converted to scale scores of 0–100. For functional domains, a higher score indicates a better function, whereas the symptom scores increase with severity of symptoms. The brain module EORTC-QLQ-BN20 (BN20) was added to evaluate functionality and symptoms originated in the central nervous system. Scale scores of 0–100 were calculated, 100 being the best function in functional scales and 100 being the worst symptom in symptom scales. The Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [35] covered sleep quality. Seven sub-component scores were calculated and cumulated into a global sleep quality score. A global score of five or higher indicated clinically significant deteriorated sleep quality. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)[36] comprised seven items related to anxiety and seven items related to depression. Each question was awarded 0–3 points, and cumulated scores of eight or more in either anxiety or depression scales were considered clinically significant. Patient’s Assessment of Own Functional Inventory (PAOFI) assessed participants’ own perception of higher cerebral functions divided into four different domains; ‘memory’, ‘language’, ‘motor-perceptual functions’, and ‘higher cognitive functions’. Each question was scored on a Likert scale from 1 to 6, and cumulated scores for items with reference to each domain were calculated in accordance with Van Dyk et al.[37]. For the correlation analysis of self-reported cognitive capacity and objectively measured cognitive functioning, the domain ‘Memory’ was tested against the outcomes ‘HVLT-delayed’, ‘HVLT-total’, and ‘WAIS-Digit span’. The domain ‘Language’ was tested against ‘COWAT-S’ and ‘COWAT-animal’. The domain ‘Higher Cognitive Functions’ was tested against ‘TMT-B’, ‘Stroop Color Word’, and ‘PASAT’. The domain ‘Motor Perceptual Function’ was tested against ‘TMT-A’ and ‘WAIS Coding’.

2.3. Radiation therapy

All participants were treated with image-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy. The prescribed radiation dose to the target volume for patients receiving primary radiotherapy was 66–68 Gy in 33–34 fractions, 5–6 weekly fractions, and for postoperative radiotherapy 60–66 Gy in 30–33 fractions, 5 weekly fractions. One patient had subsequent prophylactic whole brain irradiation with 25 Gy in 10 fractions. Doses to substructures of the brain were obtained from dose-volume histograms rigidly registered to the study MRI. Maximum dose was defined as dose to 0.027 cm3. Dose constraints for the brain was maximum 60 Gy according to the 2013th edition of DAHANCA guidelines[38].

2.4. Statistical considerations

Demographic data was analyzed using descriptive statistics. For each neurocognitive outcome and substructure volume, a Z-score was calculated based on available age- and, when available, education-adjusted normative data. A Z-score of zero represented cognitive outcomes equal to normative data, and a bootstrapped one-sided T-test was used to evaluate the probability of the Z-score being different than zero. Spearman’s Rank Correlation test was used to analyse correlations between Z-scores from the cognitive tests and radiation dose to different cerebral substructures as well as correlations between PAOFI outcomes and outcomes of objective cognitive testing. Z-scores expressing the degree of atrophy based on age-adjusted normative data were calculated, and Spearman’s Rank Correlation tests were performed for the analysis of correlation between radiation dose and atrophy. Logistic regression were used to test associations between radiation dose to different substructures and macroscopic changes visible in MRI. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, no correction for multiple testing was performed. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed in STATA v 15.0.

3. Results

Of 42 eligible patients, 27 consented and were included in the study. Median age was 67 (range 47–83), and median time from the first fraction of radiotherapy to examination was 6.4 years (range 1.6–11.1). Demographic details are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the key demographics of participants and non-participants. All participants underwent neurocognitive testing, 20 participants had cerebral MRI, all but one participant completed the questionnaires. Seven patients were included in the study without MRI due to logistic difficulties (n = 4), implanted medical devices (n = 2) and participant request (n = 1).

Table 1.

Demographic details of study participants and eligible patients, not included in the study.

| Patient characteristic | Included; n (%) | Eligible, not included; n (%) | p-value (chi-squared) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 27 (100%) | 15 (100%) | – | |

| Gender | 0.25 | ||

| Male | 17 (63) | 12 (80) | |

| Female | 10 (37) | 3 (20) | |

| Age | |||

| ≤65 | 11 (41) | () | |

| >65 | 16 (59) | () | |

| Tumor site | 0.63 | ||

| Nasal cavity | 19 (70) | 11 (73) | |

| Maxillary sinus | 8 (30) | 3 (7) | |

| Sphenoid sinus | 0 | 1 (20) | |

| T-stage | 0.69 | ||

| 1 | 5 (18.5) | 4 (26.5) | |

| 2 | 8 (29.5) | 6 (40) | |

| 3 | 3 (11) | 1 (7) | |

| 4 | 11 (41) | 4 (26.5) | |

| Treatment | 0.39 | ||

| Combination of surgery and IMRT | 20 (74) | 9 (60) | |

| IMRT alone | 7 (26) | 6 (40) | |

| Histology | 0.53 | ||

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 16 (59) | 11 (73) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 5 (19) | 1 (7) | |

| Other | 6 (22) | 3 (20) | |

| Prescribed radiation dose | 0.33 | ||

| 60 Gy | 10 (37) | 3 (20) | |

| 66 Gy | 12 (44) | 11 (73) | |

| ≥68 Gy | 5 (19) | 1 (7) | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.75 | ||

| No chemotherapy | 21 (78) | 11 (73) | |

| Concomitant cisplatin | 6 (22) | 2 (13.5) | |

| Other concomitant regimes | 0 | 2 (13.5) |

3.1. Cognitive function:

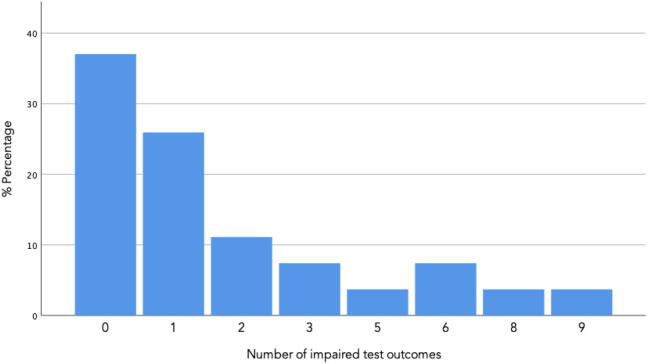

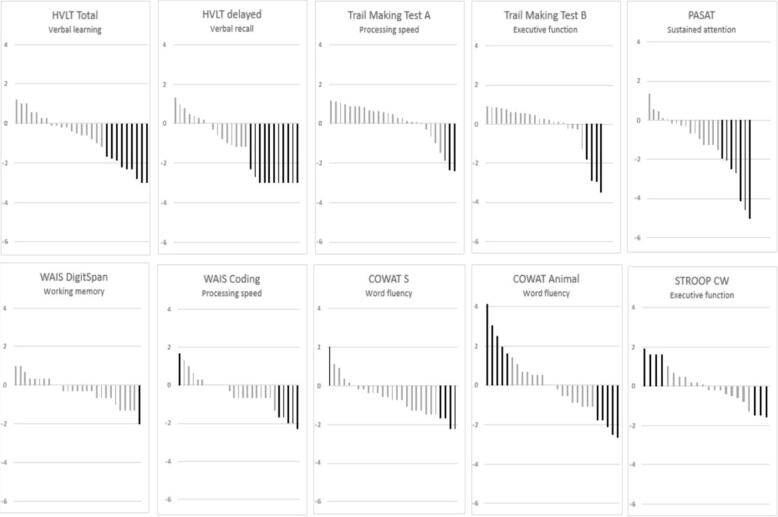

Cognitive function is evaluated with Z-scores, a negative Z-score indicating a result less than the normative value. Fig. 1 illustrates the distribution of number of impaired cognitive outcomes among the participants. Seventeen participants (63%) had impaired function in at least one cognitive outcome, and 10 participants (37%) had clinically significant cognitive impairment with a Z-score in two or more outcomes < −1.5. Mean Z-scores are shown in Table 2. Statistical significant deviations from normative data were observed in HVLT total, HVLT delayed, PASAT, coding, COWAT S, and WAIS digit span. Generally, the majority of mean scores were negative, as displayed in Fig. 2. From Table 2, it is evident, that the premorbid function assessed with WAIS Information were significantly lower than expected, indicating a cohort of generally impaired cognitive capacity prior to the cancer diagnosis. Across the cohort, the most affected outcomes were the sustained attention test PASAT (mean Z = −1.26, SD = 1.5, and four participants who did not complete the test), and the delayed verbal recall test HVLT-delayed (mean Z = −1.29, SD = 1.65). In addition, participants obtained inferior mean scores compared to normative data on tests of processing speed (WAIS coding, mean Z = −0.45, SD = 1.00), working memory (WAIS digit span, mean Z = −0.33, SD = 0.75), learning and memory (HVLT-total mean Z = −0.80, SD 1.27), and word fluency (COWAT-S mean Z −0.65, SD 1.00).

Fig. 1.

Number of impaired cognitive outcomes per patient among study participant and the distribution of number of outcomes in the study population. An impaired outcome is defined by a Z-score ≤ 1.5 in any cognitive test explained in detail in Methods.

Table 2.

Mean Z-scores of the cohort of 27 participants in each cognitive outcome, and the corresponding p-value assessing the deviation from normative data. * Actual mean test score. For WAIS information, a Z-score has not been calculated.

| Cognitive domain | Mean Z-score (SD) | p-value (bootstrapped one-sided T-test) |

|---|---|---|

Processing speed

|

0.09 (1.04) −0.45 (1.00) |

0.51 0.04 |

Executive function

|

−0.18 (1.28) 0.05 (1.06) |

0.48 0.82 |

Learning and memory

|

−0.80 (1.27) |

<0.01 |

Memory

|

−1.29 (1.52) |

<0.01 |

Working memory

|

−0.33 (0.75) |

0.02 |

Sustained attention

|

−1.26 (1.65) |

<0.01 |

Word fluency

|

0.06 (1.69) −0.65 (1.00) |

0.87 <0.01 |

| Global composite score | −0.29 (0.84) | 0.13 |

| Premorbid cognitive capacity WAIS Information |

8.6* (2.9) | 0.03 |

Fig. 2.

Neurocognitive function. Each spike represents a test result for the given outcome for a given participant (n = 27). Z-scores of 0 represent no change relative to the expected value, negative Z-scores indicate deterioration relative to the expected value, and positive Z-scores indicate a better outcome than expected. The majority of negative Z-scores in the population of the current study indicate a tendency of cognitive impairment among the study participants. Clinical significant Z-scores (<−1.5) visulaised in black. WAIS = Wechsler’s Adult Intelligence Scale, HVLT = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, COWAT = Controlled Oral Word Association Test, PASAT = Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test, Stroop CW = Stroop Color Word Test.

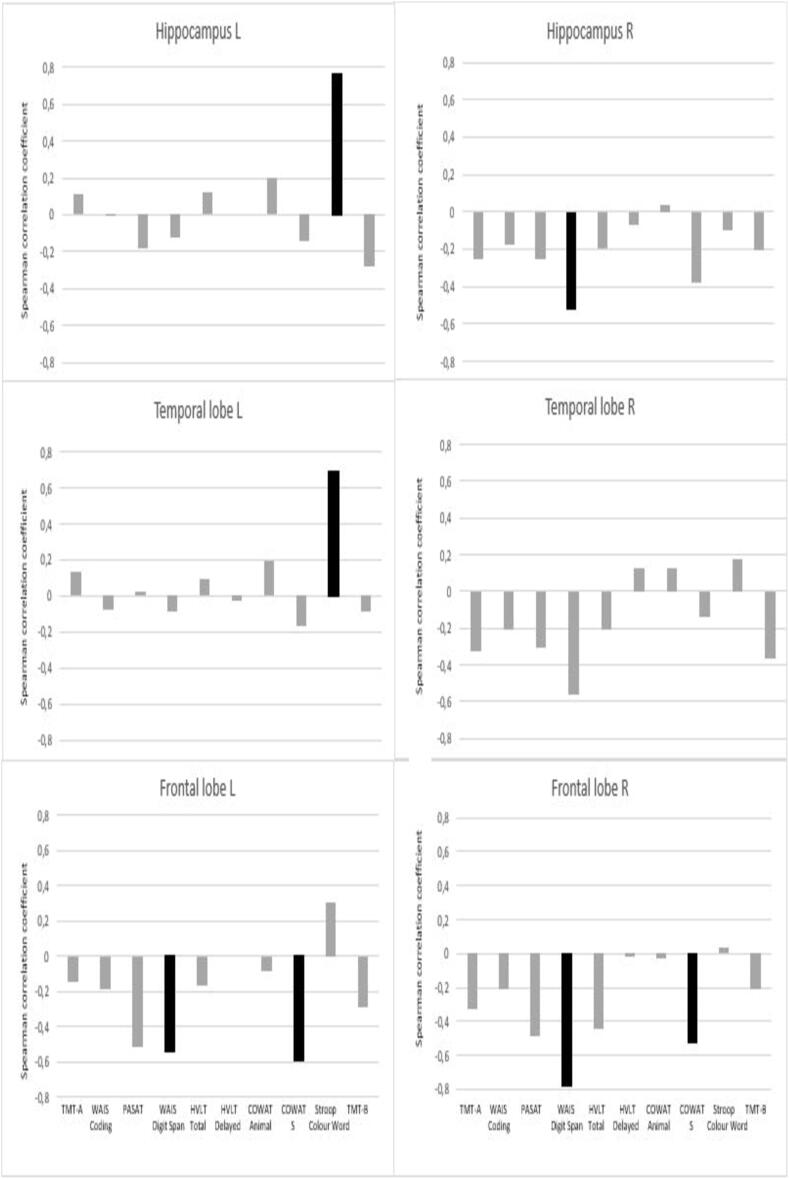

Numerous outcomes were associated with radiation dose to specific substructures (Table 3). Poorer working memory (WAIS digit span) was significantly associated with higher mean doses to the right hippocampus (p < 0.01), right temporal lobe (p = 0.01), left (p = 0.04) and right (p < 0.01) frontal lobes as well as max dose to the whole brain (p = 0.04). Poorer performance on verbal fluency (COWAT-S) was significantly associated with higher mean doses to left and right frontal lobes (p-values = 0.04). Poorer performance in sustained attention (PASAT) was associated with higher maximum dose to the whole brain (p < 0.01). A positive correlation between executive function (Stroop Color Word) and higher doses to the left hippocampus and the left temporal lobe were present (p-values < 0.01). As illustrated in Fig. 3 Radiation dose had a negative impact on most cognitive outcomes, and for several tests, a negative coefficient was present for all substructures. No associations could be detected between cognitive function and atrophy of the delineated cerebral substructures. The patient who received additional prophylactic whole brain irradiation had the lowest global composite score (−1.9), and Z-score < 1.5 in 6/10 cognitive outcomes. The analyses of cognitive outcomes across the cohort did not changes with exclusion of this patient.

Table 3.

Influence of radiation dose. The table shows mean and max doses to relevant substructures of the brain as well as Spearman correlation coefficients describing correlations between mean radiation doses to substructures and Z-scores of specific cognitive. For the whole brain, analyses have been performed using maximum doses. Spearman correlation coefficients are values between −1 and 1, the further from 0 the stronger the correlation. Statistical significant correlations are marked with bold, italic letters. TMT = Trail Making Test, WAIS = Wechsler’s Adult Intelligence Scale, PASAT = Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test, HVLT = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, COWAT = Controlled Oral Word Association Test, CW = colour word, L = left, R = right.

| Substructure |

Domain |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean dose | Max dose | Processing speed | Sustained attention | Working memory | Verbal learning & Delayed recall | Verbal fluency | Executive function | |||||

| Test | TMT A | WAIS Coding | PASAT | Digit Span | HVLT Total | HVLT delayed | COWAT Animal | COWAT S | Stroop CW | TMT B | ||

| Frontal lobe L | 6.6 | 52.7 | −0.15 | −0.19 | −0.51 | −0.54 | −0.17 | 0.00 | −0.08 | −0.59 | 0.31 | −0.29 |

| Frontal lobe R | 6.6 | 51.2 | −0.33 | −0.21 | −0.49 | −0.78 | −0.44 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.53 | 0.03 | −0.21 |

| Temporal lobe L | 12.0 | 43.4 | 0.13 | −0.08 | 0.02 | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.19 | −0.17 | 0.69 | −0.09 |

| Temporal lobe R | 12.5 | 42.6 | −0.33 | −0.21 | −0.31 | −0.56 | −0.21 | 0.13 | 0.13 | −0.14 | 0.18 | −0.37 |

| Hippocampus L | 14.1 | 22.2 | 0.11 | −0.01 | −0.18 | −0.12 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.20 | −0.14 | 0.76 | −0.28 |

| Hippocampus R | 12.9 | 22.5 | −0.25 | −0.18 | −0.25 | −0.52 | −0.20 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.38 | −0.10 | −0.21 |

| Brain | 8.5 | 53.7 | −0.23 | −0.22 | −0.59 | −0.41 | −0.26 | −0.14 | −0.04 | −0.35 | 0.22 | −0.36 |

Fig 3.

Correlation between cognitive outcomes and doses to the substructure of the brain. Each spike represents a single cognitive outcome’s correlation with the dose received by that given structure. Negative coefficients indicate a negative correlation, and a positive coefficient indicates a positive correlation. Statistical significant results are visualised in black. TMT = Trail Making Test, WAIS = Wechsler’s Adult Intelligence Scale, PASAT = Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test, HVLT = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, COWAT = Controlled Oral Word Association Test, Stroop CW = Stroop Color Word Test, R = right, L = left.

3.2. MRI

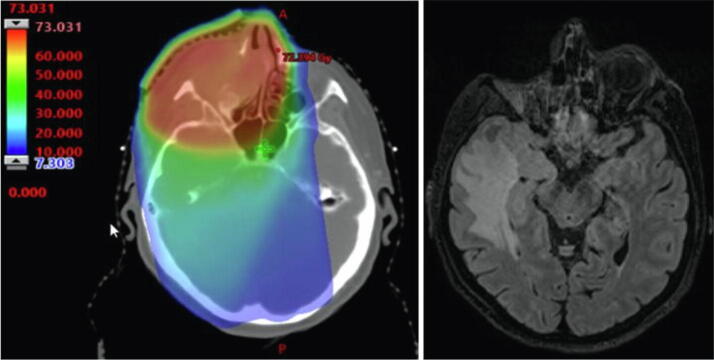

Three participants displayed macroscopic structural changes (Table 4). One participant had infarction in the posterior watershed zone. Three participants displayed voluminous, diffuse, radiation-induced white matter hyperintensities, one of which contained a radiation-induced necrosis (Fig. 4). The necrotic area had received a maximum radiation dose of of 68 Gy. The neurocognitive test of this participant revealed a severe decline in memory (HVLT-delayed Z −2.3 and HVLT-total Z −2.2), but no considerable general cognitive decline with a global cognitive Z-score of −0.6. All patients with structural alteration of brain tissue had maximum radiation doses to the brain exceeding 60 Gy. When analysing volume alterations across the cohort, no significant associations with doses to substructures were present. One patient who received a maximum dose of 69 Gy to the brain displayed negative Z-scores in all volume parameters, and a mean Z-score of −2.2 across all substructures, indicating general atrophy. The cognitive examination of this participant revealed substantial cognitive decline in the domains of processing speed, executive function, memory, attention, and word fluency.

Table 4.

Function and QoL of patients of the four participants showing macroscopic radiation induced radiation sequelae of the brain. L = left, R = right, Gy = gray, QoL = quality of life.

| PT ID | MRI finding | Anatomic location | Maximum dose to anatomic location | Global composite cognitive score | Global QoL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Diffuse White matter lesion | Bilateral frontal lobes | L: 63.2 Gy R: 62.9 Gy |

Z = -0.36 | 75.00 |

| 7 | Infarction | Posterior water shed | Z = -0.03 | 83.33 | |

| 8 |

|

Right temporal lobe | 69.7 Gy | Z = -0.6 | 66.67 |

| 9 | Diffuse white matter lesion | Bilateral Frontal lobes | L: 61.2 R: 62.5 |

Z = -0.93 | 58.33 |

Fig 4.

MRI of participant 8, showing diffuse white matter lesion in the right temporal lobe, and a necrotic area in the temporal pole, affecting both white and gray matter (study MRI, right). A substantial radiation dose has been delivered to the area (original treatment plan, left). The dose is shown in Gray, the red being areas with higher dose. The patient was enucleated following radiotherapy. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.3. Quality of life

Table 5 presents an overview of patient reported outcomes. Both C30 and BN20 questionnaires indicated sleep deprivation/fatigue as the dominant factor for deterioration of the general QoL. This is supported by PSQI, as 16 participants (59%) reported clinically significant decreased quality of sleep. Symptoms of depression and anxiety were evaluated with HADS; no participants showed symptoms of both anxiety and depression, one participant displayed symptoms of anxiety, and one displayed symptoms of depression. In the PAOFI questionnaire, displaying self-reported cognitive functioning, the domain ‘memory’ was affected the most with a mean score of 21.40 (SD 6.88). The least effect on self-reported function was in the domain ‘motor-perceptual function’, with a mean of 9.04 (SD 4.14). The correlation between self-reported cognitive capacity and objectively measured cognitive function showed significant correlations for the PAOFI domain ‘Memory’ and the outcomes ‘HVLT-delayed’ (p < 0.01) and ‘HVLT-total’ (p = 0.02), as well as the PAOFI domain ‘Language’ and the outcome ‘COWAT-S’ (p = 0.02). No normative data of PAOFI is available for comparison with this scoring system.

Table 5.

Patient reported outcome measures and estimated premorbid functioning. All repsonses are calculated to scale scores, reflecting the participants function or degree of symptoms in a given area. A total of 26 participants completed the questionnaires. For EORTC-QLQ-C30 and EORTC-QLQ-BN20 function scales (*), higher scores indicate better function and for symptom scales (**), higher scores indicate more severe symptoms.

| Patient reported outcome | Mean score (SD) | Normative value |

|---|---|---|

EORTC-QLQ-C30

|

|

Hjermstadt et al.[53]

|

| EORTC-QLQ-BN20 Functions*

|

|

|

HADS

|

|

|

PSQI

|

|

Hinz et al.[54].

|

PAOFI scale scores

|

|

4. Discussion

The results of our study indicate substantial impact on neurocognitive functions after radiotherapy for SNC. PASAT and HVLT-delayed were the most affected neurocognitive outcomes, displaying impairment in the cognitive domains of attention and memory. Furthermore, dose–response correlations were found across several substructures of the brain, including dose to the whole brain, right temporal lobe, both frontal lobes and hippocampi and outcomes of WAIS-digit span, both frontal lobes and COWAT-S as well as maximum dose to the whole brain and PASAT.

Neurocognitive impairment after SNC treatment has only been evaluated in one previous study (Meyer et al, 2000) [39], that investigated long-term impairment in 19 patients treated for SNC between 1971 and 1994. They found radiation dose to be significantly associated with impaired HVLT-delayed recall, and a prescribed mean dose of 60 Gy associated with impaired memory recall. Cognitive decline following radiotherapy is widely investigated in nasopharyngeal tumours [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], all studies concluding that radiotherapy caused various degrees of neurocognitive impairment. Nasopharyngeal tumours are most often located more posteriorly than sinonasal tumours, and therefore larger radiation doses are usually delivered to the frontal and the temporal lobe of the brain. The results are thus indicative of a dose-related functional impairment of relevance also to SNC radiotherapy. In addition, a number of studies have investigated cognitive function in patients treated for head and neck cancer in general, the majority of which did not include SNC. Williams et al. (2017) [45] showed mild cognitive decline in the majority of patients with head and neck cancer, however not related to the radiation dose, but to various demographic factors. These results indicate that multiple etiologic factors are at play in the development of cognitive impairment in head and neck cancer patients. Apart from wide etiology, the evaluation of the literature is further challenged by a wide variety of instruments used for assessment of neurocognitive function, regardless of initiatives to unify the methods [29]. In spite of the complex endpoints and varying methods for evaluation, much focus of the literature is directed towards radiation of hippocampus as the main driver for cognitive decline following radiotherapy. Thus, much effort has been put into sparing hippocampus with the aim of decreasing the degree of subsequent cognitive impairment. Gondi et al. [22] proposed a threshold dose of 7.3 Gy given to 40% of bilateral hippocampi in order to reduce the risk of cognitive decline. The model of Gondi did not have any predictive value in our dataset (data not shown), similar to the validation of Jaspers et al. [46] (2019) in a cohort of patients with low-grade gliomas. However, a large prospective study published in 2020 by Brown et al. [47] evaluated cognitive failure and the model proposed by Gondi et al. in patients with brain metastases receiving whole brain irradiation of 30 Gy in 10 fractions. They concluded that the cognitive failure rate was significantly reduced in patients receiving hippocampal sparing radiotherapy compared to conventional whole brian irradiation. The laterality of hippocampal irradiation is continously under investigation. The current study found correlations between impaired working memory and radiation doses to the right hippocampus and between executive function and doses to the left hippocampus. The sample size in the current study is too narrow to suggest threshold doses or changes in treatment practice; for this purpose, a larger, prospective study would be required. To conclude, endpoints are complex, and the results from studies with intra- and extracranial tumours differ, possibly as direct effects of the tumour as well as other intracranial treatments will have additional impact on the function of the brain.

In the evaluation of late radiation sequelae, the aspect of QoL is central. Analyses from the current study did not reveal any correlation between cognitive decline and global QoL. It is however important to take into account that a mild cognitive decline might not be reflected in deteoriation of the general QoL. Multiple factors affect the QoL, challenging the assessment of cognitive decline itself. In the current analysis, ‘fatigue’, ‘insomnia’, and ‘drowsiness’ were the most severe self-reported symptoms and 59% had poor quality of sleep. Studies have concluded that poor quality of sleep has a negative impact on the cognitive function. Thus, both deteoriated sleep and radiotherapy may lead to cognitive decline, and radiotherapy may lead to poor quality of sleep. The relative weight of these factors in the development of cognitive decline and global QoL continues to be subject for investigation. Prospective studies focusing on these correlations are pertinent.

One participant had asymptomatic temporal lobe necrosis following radiotherapy. The only reports on temporal lobe necrosis in SNC patients are descriptive studies and case reports by Ahmad et al. [48] and Madhava et al. [49]. The correlation between macroscopic cerebral changes such as temporal lobe injury and cognitive decline has been investigated in a study by Lam et al. [42], who concluded that temporal lobe injury in patients treated for nasopharyngeal cancer was associated with cognitive decline. Similarly, Cheung et al. [50] concluded that radiation necrosis was associated with impaired cognitive function in patients treated for nasopharyngeal cancer, particularly in the domains of verbal memory and language. The participant in our study with temporal lobe necrosis also had severe impairment of memory functions. Guo et al. [51] and Lv et al. [52] investigated volume changes in a prospective setting in patients who received radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal cancer. They found volumes of the ventricles and hippocampus substantially changed following radiotherapy. In our study, no significant correlations between dose to substructures and Z-scores describing volume changes could be detected, and cognitive decline could likewise not be associated with cerebral atrophy. The assessment of atrophy on a substructure-level based on normative data will easily miss detailed coherences. An important aspect of assessing functionality of the brain is microscopic tissue damage, as it might impact the function of the brain. Microscopic alteration can be visualised on diffusional MRI imaging, which would be relevant to incorporate in the development of dose–response models for brain tissue.

The strength of the current study lies in its comprehensive nature investigating both neurocognitive functioning, objective evaluation of macroscopic tissue alterations, and the impact on the QoL. Furthermore, patients with SNC are appropriate for the investigation of radiation-induced cerebral toxicity, as intracranial spread and intracranial surgery is rare, thus evading two major confounders.

The current study carries some limitations; first, the study cohort is relatively small. With SNC, it is, however, difficult to collect large cohorts due to the rarity of the disease as well as the poor prognosis. In our study, 64% of eligible patients accepted inclusion. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study with no available baseline data does not allow for the detection of actual changes in neurocognitive functioning or cerebral morphology. In order to minimise the uncertainty and effect of confounders in the current study, we used age-adjusted normative data based on large materials, and for PASAT, the normative data were adjusted to education levels as well. With a lack of control group, the normative data offers an opportunity for interpreting the results, which is a standard approach within the field of neuropsychology. Cognitive function might be affected by other confounding factors; even though the brain is rarely affected by intracranial tumour growth or intracranial surgery, the large fraction of patients who underwent surgery has been through a more extensive course of treatment and stay in intensive care units, potentially affecting cognitive capacity. Regarding the entire cohort, cognitive function might too be affected by the cancer diagnosis itself, other medication, or subclinical recurrence. Only one patient were diagnosed with recurrent disease following participation in the study, 16 months after study examinations.

As cognitive function and the cerebral tissue itself may be affected by several other factors, as well as the development of cognitive impairement over time, the results of the current study call for larger prospective data collections with baseline assessments and timed follow up examinations. The Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA) has launched such a prospective study (DAHANCA 36).

In conclusion, we found substantial late toxicity in the brain, both macroscopic changes and functional impairment. More than one third of the patients displayed clinically significant cognitive impairment, and dose response correlations were present for dose to both frontal lobes, both hippocampi and the right temporal lobe. Macroscopic radiation sequeleae were present as well, indicating considerable impact of radiotherapy in brain tissue. Based on the results from the current study, a prospective national study has been initiated, and a study investigating proton and photon therapy is planned, including the generation of a NTCP model for cerebral toxicity after radiotherapy for SNC.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by The Danish Cancer Society (grant R167-A10968), Aarhus University, the Danish Cancer Research Foundation and the Health Research Fund of Central Denmark Region.

References

- 1.Birgi S.D., Teo M., Dyker K.E. Definitive and adjuvant radiotherapy for sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas: a single institutional experience. Radiat Oncol. 2015;10:190. doi: 10.1186/s13014-015-0496-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robin TP, Jones BL Gordon OM, et al. A comprehensive comparative analysis of treatment modalities for sinonasal malignancies. Cancer, 2017;123:3040–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Thorup C., Sebbesen L., Danø H. Carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses in Denmark 1995–2004. Acta Oncol. 2010;49:389–394. doi: 10.3109/02841860903428176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camp S., Van Gerven L., Poorten O.M. Long-term follow-up of 123 patients with adenocarcinoma of the sinonasal tract treated with endoscopic resection and postoperative radiation therapy. Head Neck. 2016;38:294–300. doi: 10.1002/hed.23900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendenhall W.M., Amdur R.J., Morris C.G. Carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:899–906. doi: 10.1002/lary.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darzy K.H. Radiation-induced hypopituitarism. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20:342–353. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283631820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sathyapalan T., Dixit S. Radiotherapy-induced hypopituitarism: a review. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12:669–683. doi: 10.1586/era.12.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chi A, Nguyen NP, Tse W, et al. Intensity modulated radiotherapy for sinonasal malignancies with a focus on optic pathway preservation. J Hematol Oncol, 2013;6:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Jeganathan V.S.E., Wirth A., MacManus M.P. Ocular risks from orbital and periorbital radiation therapy: a critical review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:650–659. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacob J., Durand T., Fuvret L. Cognitive impairment and morphological changes after radiation therapy in brain tumors: a review. Radiother Oncol. 2018;128:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haldbo-Classen L., Amidi A., Wu L.M. Long-term cognitive dysfunction after radiation therapy for primary brain tumors. Acta Oncol. 2019;58:745–752. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1557786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrie T.A., Gillespie D., Dowswell T. Long-term neurocognitive and other side effects of radiotherapy, with or without chemotherapy, for glioma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013047.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cramer C.K., McKee N., Case L.D. Mild cognitive impairment in long-term brain tumor survivors following brain irradiation. J Neurooncol. 2019;141:235–244. doi: 10.1007/s11060-018-03032-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karunamuni R, Bartsch H, White NS, et al. Dose-dependent Thinning After Cortical Partial Brain Radiation in High-grade Glioma, 2016;94:297–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Armstrong C.L., Hunter J.V., Ledakis G.E. Late cognitive and radiographic changes related to radiotherapy: initial prospective findings. Neurology. 2002;59:40–48. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seibert T.M., Karunamuni R., Bartsch H. Radiation dose-dependent hippocampal atrophy detected with longitudinal volumetric magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97(2):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seibert TM, Karunamuni R, KAifi S, et al. Cerebral cortex regions selectively vulnerable to radiation dose- dependent atrophy Tyler, Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2017;97:910–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Lawrence Y.R., Li A., El-Naqa E. Radiation dose-volume effects in the brain. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:S20–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeshita Y., Watanabe K., Kakeda S. Early volume reduction of the hippocampus after whole - brain radiation therapy : an automated brain structure segmentation study. Jpn J Radiol. 2020;38:118–125. doi: 10.1007/s11604-019-00895-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gui C., Chintalapati N., Kenneth R. A prospective evaluation of whole brain volume loss and neurocognitive decline following hippocampal - sparing prophylactic cranial irradiation for limited - stage small - cell lung cancer. J Neurooncol. 2019;144:351–358. doi: 10.1007/s11060-019-03235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujii O, Tsujino K, Soejima T, et al. White matter changes on magnetic resonance imaging following whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases, 2006:345–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Gondi V., Hermann B.P., Mehta M.P. Hippocampal Dosimetry Predicts Neurocognitive Function Impairment After Fractionated Stereotactic Radiotherapy for Benign or Low-Grade Adult Brain Tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reitan R. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Recept Mot Ski. 1958 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiens A.N., Fuller K.H., Crossen J.R. Paced Auditorial Serial Addition Test: Adult Norms and Moderator Variables. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1997;19:473–483. doi: 10.1080/01688639708403737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - fourth edition (WAIS-IV), San Antonio; 2008.

- 26.Benedict R.H.B., Schretlen D., Groninger L. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test - Revised: Normative data and analysis of interform and test-retest reliability. Clin Neuropsychol. 1998;12:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thurstone L. Primary Mental Abilities. Science. 1948;108:585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stroop J.R. Stroop Color Word Test. J Exp Psychol. 1935;18:643–662. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wefel J.S., Vardy J., Ahles T. International Cognition and Cancer Task Force recommendations to harmonise studies of cognitive function in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:703–708. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aubert-Broche B., Fonov V.S., Garzia-Lorenzo D. A new method for structural volume analysis of longitudinal brain MRI data and its application in studying the growth trajectories of anatomical brain structures in childhood. Neuroimage. 2013;82:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fonov V., Evans A.C., Botteron K. Unbiased Average Age-Appropriate Atlases for Pediatric Studies. Neuroimage. 2011;54:311–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coupé P., Manjón J.V., Fonov V. Patch-based segmentation using expert priors: Application to hippocampus and ventricle segmentation. Neuroimage. 2011;54:940–954. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Avants B.B., Tustison N.J., Stauffer M. The Insight ToolKit image registration framework. Front Neuroinform. 2014;8:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2014.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aaronson N.K. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buysse D.J., Reynolds C.F., Monk T.H. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zigmond A.S., Snaith R. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Dyk K., Ganz P.A., Ercoli L. Measuring cognitive complaints in breast cancer survivors: psychometric properties of the patient’s assessment of own functioning inventory. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:4939–4949. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3352-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DAHANCA, Retningslinjer for strålebehandling i DAHANCA, 2013. https://dahanca.dk/assets/files/GUID_DAHANCA%20Radiotherapy%20Guidelines.pdf

- 39.Meyers C.A., Geara F., Wong P.F. Neurocognitive effects of therapeutic irradiation for base of skull tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:51–55. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hua M.S., Chen S.T., Tang L.M. Neuropsychological function in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma after radiotherapy. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20:684–693. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.5.684.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsiao K.Y., Yeh S.A., Chang C.C. Cognitive function before and after intensity-modulated radiation therapy in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:722–726. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lam L.C.W., Leung S.F., Chan Y.L. Progress of Memory Function After Radiation Therapy in Patients With Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;151:90–97. doi: 10.1176/jnp.15.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheung M., Chan A.S., Law S.C. Cognitive function of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma with and without temporal lobe radionecrosis. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:1347–1352. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.9.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee W.P.H., Hung K.M., Woo E.K.W. Effects of radiation therapy on neuropsychological functioning in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Neurol Neurosurgery Psychiatry. 1989;52:488–492. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.52.4.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams A.M., Lindholm J., Siddiqui F. Clinical Assessment of Cognitive Function in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer: Prevalence and Correlates. Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2017;157:808–815. doi: 10.1177/0194599817709235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jaspers J. Evaluation of the Hippocampal Normal Tissue Complication Model in a Prospective Cohort of Low Grade Glioma Patients — An Analysis Within the EORTC 22033 Clinical. Trial. 2019;9:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown P.D. Hippocampal avoidance during whole-brain radiotherapy plus memantine for patients with brain metastases: Phase III trial NRG oncology CC001. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1019–1029. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmad S., Le C.H., Chiu A.G. Incidence of intracranial radiation necrosis following postoperative radiation therapy for sinonasal malignancies. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:2445–2450. doi: 10.1002/lary.26106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kanakamedala M.R., Mahta A., Liu J. Late temporal lobe necrosis after conventional radiotherapy fo66r carcinoma of maxillary sinus. Med Oncol. 2012;29:2456–2458. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheung M.C., Chan A.S., Law S.C. Impact of radionecrosis on cognitive dysfunction in patients after radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:2019–2026. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo Z. Clinical Longitudinal brain structural alterations in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma early after radiotherapy. NeuroImage Clin. 2018;19:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lv X. Radiation-induced hippocampal atrophy in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma early after radiotherapy : a longitudinal MR-based hippocampal subfield analysis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2019;13:1160–1171. doi: 10.1007/s11682-018-9931-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hjermstad M.J., Fayers P.M., Bjordal K. Health-Related Quality of Life in the General Norwegian Population Assessed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-life Questionnaire, the qlq-C30. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1188–1196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hinz A. Sleep quality in the general population: psychometric properties of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, derived from a German community sample of 9284 people. Sleep Med. 2017;30:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]