Abstract

This cohort study identifies trends in tyrosine kinase inhibitor use in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia and the association those treatment choices have with health care costs.

The increasing price of new cancer therapies over the past 3 decades has contributed considerably to increasing health care expenditures. The life expectancy of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) treated with imatinib now approaches that of the general population, increasing the prevalence of survivors with CML receiving treatment.1 Beginning in 2006, a series of second- and third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been approved and gained widespread use based on early results demonstrating deeper molecular responses.2,3 However, subsequent studies have provided no evidence that later-generation TKIs provide superior progression free or overall survival compared with imatinib.4,5,6 Although a generic imatinib was approved in 2016, high initial prices of brand name and generic imatinib and next-generation TKIs have continued to increase, averaging 10% to 20% annually, contributing to financial hardship and possibly poor compliance with effective therapy (https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JOP.2016.019737). In this article, we provide contemporary data to identify trends in TKI use in patients with CML and the association those treatment choices have with health care costs.

Methods

Health plan enrollees initiating treatment with a TKI (eg, imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, bosutinib, or ponatinib) from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2019, were identified in the OptumLabs Data Warehouse. The database contains deidentified medical and pharmacy claims information on commercial and Medicare Advantage enrollees. Because this study involved analysis of preexisting, deidentified data, it was exempt from institutional review board approval and informed consent according to the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Eligible patients had received a diagnosis of CML (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] code 205.1x or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] code C92.1x) and enrolled at least 6 months before their first TKI prescription fill. Patients who underwent stem cell transplant before starting a TKI were excluded. We identified choice of first-line TKI, switching to another TKI, and health care costs in the first year of treatment (the latter 2 requiring 12 months of enrollment following TKI initiation). First-year TKI costs are reported as cost per TKI treatment day ([health plan + patient paid amount]/total days’ supply). All analyses were conducted using Stata, version 14.2 (StataCorp).

Results

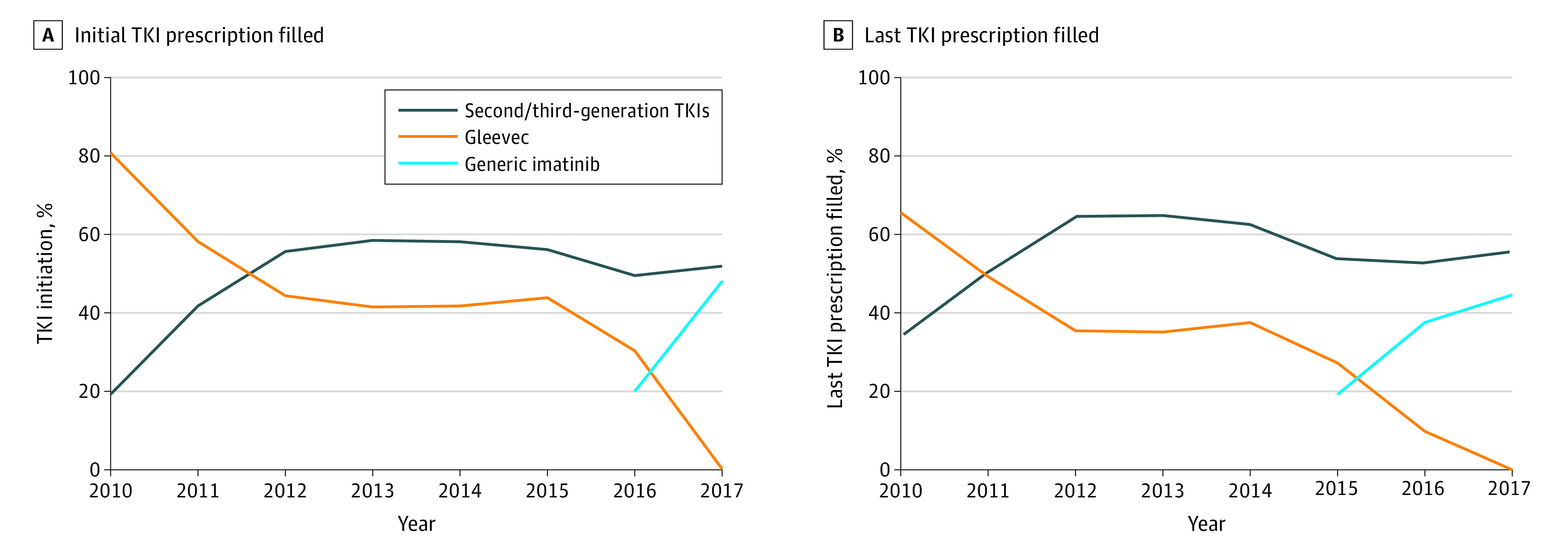

The proportion of patients beginning to take a second- or third-generation drug (eg, dasatinib, nilotinib, bosutinib, or ponatinib) increased from 28 of 148 (19%) in 2010 to 146 of 263 (56%) in 2019 (Figure, A). Approximately 1 in 4 switched from their initial TKI within the first year of treatment (Table). By the end of the first year of treatment, second- or third-generation TKI use rose from 37 of 108 (34%) to 137 of 213 (64%) from 2010 to 2018 (Figure, B).

Figure. Initial and Last Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor (TKI) Prescription Filled During the First Year of TKI Treatment.

Because of the risk of reidentification associated with reporting small cell sizes, Gleevec use below 5% is reported as 0%, and generic imatinib is rounded up (assuming 0% Gleevec use).

Table. Trend in TKI Switching and Costs in First Year of Treatmenta.

| Year of treatment initiation | No. | Switching, No. (%) | Days’ supply, median (IQR) | TKI cost per treated day, mean (95% CI), $b,c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | HPP | OOP | ||||

| 2010 | 108 | 17 (16) | 346 (268-365) | 243 (228-259) | 232 (86-232) | 13 (13-35) |

| 2011 | 146 | 26 (18) | 352 (300-365) | 275 (263-286) | 263 (72-263) | 10 (10-19) |

| 2012 | 161 | 36 (23) | 336 (264-360) | 283 (272-294) | 274 (76-274) | 10 (10-16) |

| 2013 | 131 | 26 (20) | 350 (270-365) | 305 (294-317) | 290 (73-290) | 12 (12-21) |

| 2014 | 144 | 27 (20) | 353 (307-365) | 350 (338-362) | 336 (84-336) | 14 (14-25) |

| 2015 | 147 | 31 (22) | 331 (255-363) | 367 (355-378) | 355 (81-355) | 12 (12-17) |

| 2016 | 173 | 39 (24) | 336 (268-364) | 353 (338-369) | 345 (106-345) | 9 (9-15) |

| 2017 | 202 | 38 (20) | 344 (280-365) | 343 (323-364) | 330 (143-330) | 13 (13-19) |

| 2018 | 213 | 45 (23) | 321 (240-352) | 354 (325-383) | 346 (161-346) | 11 (11-22) |

Abbreviations: CPI, consumer price index; HPP, health plan paid amount; IQR, interquartile range; OOP, patient out-of-pocket responsibility; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Patients are required to have 1 year of continuous enrollment following TKI treatment initiation.

Because of the availability of health plan cost information for the entire year following treatment initiation, the 2018 sample size was 128.

Calculated as health plan + patient paid amount for TKI divided by total days’ supply in the first year. Costs are converted to 2018 dollars using the medical component of the CPI.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor costs are the largest driver of heath care expenditures in patients with CML, representing 66% of first-year spending for Medicare Advantage members in 2018 and 65% for commercial enrollees (https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/OP.20.00143). Tyrosine kinase inhibitor costs per day have increased from $243 for those undergoing treatment in 2010 to $354 in 2018 (Table).

Discussion

Despite the lack of evidence for an overall survival difference between first- or second-generation TKIs, most patients with CML are now prescribed a second-generation TKI in the US.4,5,6 Despite a National Average Drug Acquisition Cost price for generic imatinib as low as $20 per 400-mg tablet in 2018, the average TKI costs per day exceeded $350, largely driven by the decision to treat patients with CML with more costly second-line TKIs (https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/OP.20.00143). High costs may result in treatment delays, poor compliance, or early termination of effective therapy, leading to poorer outcomes for individuals with a treatable and potentially curable malignancy. While the US patent on dasatinib expires in October 2025, the association with generic TKI uptake may still be limited given other later-generation TKIs remaining on patent beyond 2030. Our results are limited to data from managed care enrollees, which may not reflect the experience of other populations (eg, those without insurance or those receiving Medicaid).

In conclusion, generic price competition alone may be insufficient to reduce the price of cancer drugs in the US. Another potential driver is delays in some pharmacies passing on lower acquisition prices. Policies that address rising cancer drug prices and overall health care expenditures must be of the highest priority for clinicians, payers, patient advocates, and policy makers moving forward.

References

- 1.Bower H, Björkholm M, Dickman PW, Höglund M, Lambert PC, Andersson TM. Life expectancy of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia approaches the life expectancy of the general population. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2851-2857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.2866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Hochhaus A, et al. Dasatinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2260-2270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saglio G, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S, et al. ; ENESTnd Investigators . Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2251-2259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortes JE, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Deininger MW, et al. Bosutinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia: results from the randomized BFORE trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(3):231-237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.7162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortes JE, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM, et al. Final 5-Year study results of DASISION: the Dasatinib Versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naïve Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(20):2333-2340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hochhaus A, Saglio G, Hughes TP, et al. Long-term benefits and risks of frontline nilotinib vs imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: 5-year update of the randomized ENESTnd trial. Leukemia. 2016;30(5):1044-1054. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]