Abstract

Purpose

To assess the effect of venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) compared to conventional management in patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) performed after Jan 1, 2000 comparing ECMO to conventional management in patients with severe ARDS. The primary outcome was 90-day mortality. Primary analysis was by intent-to-treat.

Results

We identified two RCTs (CESAR and EOLIA) and combined data from 429 patients. On day 90, 77 of the 214 (36%) ECMO-group and 103 of the 215 (48%) control group patients had died (relative risk (RR), 0.75, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.6–0.94; P = 0.013; I2 = 0%). In the per-protocol and as-treated analyses the RRs were 0.75 (95% CI 0.6–0.94) and 0.86 (95% CI 0.68–1.09), respectively. Rescue ECMO was used for 36 (17%) of the 215 control patients (35 in EOLIA and 1 in CESAR). The RR of 90-day treatment failure, defined as death for the ECMO-group and death or crossover to ECMO for the control group was 0.65 (95% CI 0.52–0.8; I2 = 0%). Patients randomised to ECMO had more days alive out of the ICU and without respiratory, cardiovascular, renal and neurological failure. The only significant treatment-covariate interaction in subgroups was lower mortality with ECMO in patients with two or less organs failing at randomization.

Conclusions

In this meta-analysis of individual patient data in severe ARDS, 90-day mortality was significantly lowered by ECMO compared with conventional management.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00134-020-06248-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Adult patients, Individual patient data meta-analysis

Take home message

| In this meta-analysis of individual patient data in severe ARDS, 90-day mortality was significantly lowered by ECMO compared with conventional management. Patients randomised to ECMO had more days alive out of the ICU and without respiratory, cardiovascular, renal and neurological failure |

Introduction

Ventilatory management of patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) has improved over the last decades with a strategy combining low tidal volume (VT) ventilation [1], high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) [2, 3], neuromuscular blocking agents [4] and prone positioning [5]. However, ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) may persist in these patients since a recent and large epidemiological study showed that their hospital mortality was still 46% [6]. Recently, even higher mortality was reported for patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection who needed invasive mechanical ventilation [7–9].

Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) providing full blood oxygenation, CO2 elimination and combined with more gentle ventilation has benefited from major technological advances in the last 15 years [10, 11]. In 2009, favourable outcomes were reported in patients who received ECMO during the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic [12–14]. The Conventional Ventilator Support vs Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Failure (CESAR) trial [15, 16] showed that transfer to an ECMO centre was associated with fewer deaths or severe disabilities at 6 months compared with conventional mechanical ventilation (37% vs. 53%; p 0 = 0.03), although 6 month mortality was not significantly reduced (37% vs. 45%; p = 0.07). The more recent ECMO to Rescue Lung Injury in Severe ARDS (EOLIA) trial showed a non-statistically significant reduction in 60-day mortality with ECMO (35% vs. 46%; p = 0.09) [17]. However, neither trial was separately powered to detect a 10–15% survival benefit with ECMO.

We performed a systematic review with an individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials comparing ECMO to conventional mechanical ventilation in patients with severe ARDS. The primary objective was to evaluate the effect of ECMO on 90-day mortality. Secondary objectives included the evaluation of ECMO for other clinical outcomes and in pre-specified subgroups for the primary outcome.

Methods

Study design

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses for Individual Patient Data (PRISMA-IPD checklist in eTable 1 in the Supplement) and the protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42019130034) on May 1st 2019.

Eligibility criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating venovenous ECMO in the experimental group and conventional ventilatory management in the control group, that included patients with ARDS fulfilling the American–European Consensus Conference definition [18] or the Berlin definition for ARDS [19], and that were published or whose primary completion date was after 2000 [10, 20, 21]. This choice was justified by the major improvements in intensive care treatments and in ECMO technology that occurred in the last two decades. Additional information on selection criteria is provided in the Supplement.

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE via PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Central) from January 1, 2000 to September 30, 2019 using a search algorithm developed for the purpose of this study and adapted to each database (eTable 2 in the Supplement). We also searched trial registries including ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Clinical Trial Registry Platform (ICTRP) for completed and ongoing trials, conference proceedings of major critical care societies and screened reference lists of identified articles as well as systematic or narrative reviews on the topic (see the Supplement).

Selection and data collection

Selection was conducted independently by two reviewers (DA and MS) on titles and abstracts first and then, on the full text. For each included RCT, the corresponding author was contacted to provide fully anonymized individual patient data as well as format, coding and definition of any variables. Risk of bias in each trial was evaluated by two independent reviewers (DH and AD) using the updated version of the risk-of-bias tool developed by Cochrane [22] (see the Supplement).

Study outcomes

The primary endpoint was mortality 90 days after randomisation. Main secondary endpoints comprised time to death up to 90 days after randomisation, treatment failure up to 90 days, defined as crossover to ECMO or death for patients in the control group, and death for patients in the ECMO group, number of days alive and out-of-hospital between randomisation and day 90, number of days alive without mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy and vasopressor support between randomisation and day 90. Other preplanned secondary outcomes comprised mortality at 28 and 60 days after randomisation, number of days alive and out of the ICU between randomisation and day 90, number of days alive without respiratory failure, neurological failure, cardiovascular failure, liver failure, renal failure and coagulation failure, defined as the corresponding component sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score greater than 2 between randomisation and day 90. Data related to patients’ management, causes of death and safety outcomes were also described (see the Supplement).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed for each outcome of interest using individual patient data. An intention-to-treat analysis was used for all outcomes, whereby all patients were analysed in the groups to which they were randomised. The measures of treatment effect were risk ratios for binary outcomes, hazard ratios for time-to-event outcomes and mean differences for quantitative outcomes. The primary endpoint was defined as a binary outcome and analysed using both one-step (as primary analysis) and two-steps (as sensitivity analysis) methods [23]. In the one-step method, we analysed both studies simultaneously to obtain the combined treatment effect with 95% CIs and p-value using a generalized linear mixed effect model to account for the clustering of data within each trial with a random effect. In the two steps method, we first analysed separately each trial using individual patient data before combining them using a random effects meta-analysis model to account for variability between studies. A two-step method was used for all secondary outcomes. Heterogeneity was evaluated with the Cochran's Q-test, I2 statistic and between study variance τ2. Survival curves for the time to death up to 90 days were generated using individual patient data and the Kaplan–Meier method.

We conducted sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome in different populations (per-protocol, as-treated). The per-protocol population included all randomised patients having received the treatment attributed by randomisation (i.e., patients having received ECMO in the ECMO arm and patients not having received ECMO in the control arm). The as-treated population compared patients receiving ECMO to those who did not receive ECMO, whatever the randomisation arm. A sensitivity analysis excluding trials at high risk of bias was also planned.

We explored whether the effect of ECMO on 90-day mortality varied according to baseline patient characteristics (see the Supplement). For each subgroup, the treatment-subgroup interaction was tested in the one-step model. For quantitative baseline characteristics, we used the median values to define the subgroups. All these subgroup analyses were pre-planned.

Alpha risk was set at 5% for the primary outcome. For all secondary outcomes, we did not correct for multiple testing. As such, subgroup and sensitivity analyses should be considered as exploratory. All the analyses were performed with the use of R software version 3.6.1 (R Foundation).

The quality of evidence for the seven most important outcomes was graded with GRADEpro GDT (GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool [Software]; McMaster University, 2015 (developed by Evidence Prime, Inc.; Available from gradepro.org).

Results

Selection process and general characteristics

From the 1179 references identified by the search strategy, we included two randomised controlled trials fulfilling our eligibility criteria—CESAR and EOLIA [15, 17]. Reasons for exclusion are reported in eFig. 1 of the Supplement. The two trials provided individual patient data for all randomised patients (429 overall, 180 in CESAR and 249 in EOLIA), and there was no eligible trial not providing individual patient data. Detailed characteristics of the two trials are reported in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Comparison of patient characteristics at randomisation did not show baseline imbalance between groups (Table 1 and eTables 4 and 5 in the Supplement). The main disorder leading to study entry was severe hypoxia (in 88% of the patients, with a mean (± SD) PaO2/FiO2 of 75 ± 34 mm Hg). The main cause of ARDS was pneumonia (> 60% of the patients) and 39% had 3 or more organs failing at randomisation. Of the 214 patients randomised to the ECMO groups, 189 (88%) received ECMO (98% and 76% in EOLIA and CESAR, respectively). Rescue extracorporeal gas exchange was used for 36 (17%) of the 215 control patients (35 patients crossed over to ECMO in EOLIA, and 1 to pumpless arteriovenous CO2 removal in CESAR that was a protocol violation by the conventional management team as rescue extracorporeal gas exchange was not part of the CESAR trial design). Risk of bias was judged low in both trials (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients at randomisation

| Characteristic | ECMO group (N = 214) | Control group (N = 215) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 46.6 ± 15.2 | 48.3 ± 14.8 |

| Male—no. (%) | 138 (65) | 143 (67) |

| Median (interquartile) time since intubation, h | 35 [16–95] | 36 [16–100] |

| ARDS aetiology—no. (%) | ||

| Pneumonia | 136 (64) | 131 (61) |

| Other | 78 (36) | 84 (39) |

| 3 or more organs faileda | 82 (38) | 84 (39) |

| Predicted mortalityb | 0.34 ± 0.23 | 0.34 ± 0.22 |

| PaO2/FiO2 | 76 ± 35 | 75 ± 33 |

| pH | 7.30 ± 0.37 | 7.26 ± 0.24 |

| Disorder leading to study entry | ||

| Hypoxia | 184 (86%) | 192 (89%) |

| Uncompensated hypercapnia | 30 (14%) | 23 (11%) |

| PEEP, cm H2O | 12.3 ± 6.8 | 12.7 ± 6.8 |

| Respiratory system compliance, ml/cm H2O | 25.8 ± 11.8 | 25.3 ± 8.8 |

| Murray score | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 0.4 |

| Chest radiograph (quadrants infiltrated) | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 3.5 ± 0.8 |

Plus–minus values are means ± SD; see eTable 5 the Supplement for missing data

ECMO denotes extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ARDS the acute respiratory distress syndrome, PaO2 partial pressure of arterial oxygen, FiO2 the fraction of inspired oxygen, PaO2/FiO2 the ratio of the partial pressure of arterial oxygen to the fraction of inspired oxygen, PEEP positive end-expiratory pressure

Missing data were < 3% for patients’ characteristics at randomisation, except for predicted mortality, respiratory system compliance and Murray score (see eTable 5 in the Supplement)

aNumber of organ failed (0–6) defined as the corresponding component sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score > 2

bAPACHE2 (CESAR) and SAPS2 (EOLIA) scores were both translated to predicted probability of ICU mortality

Primary outcome

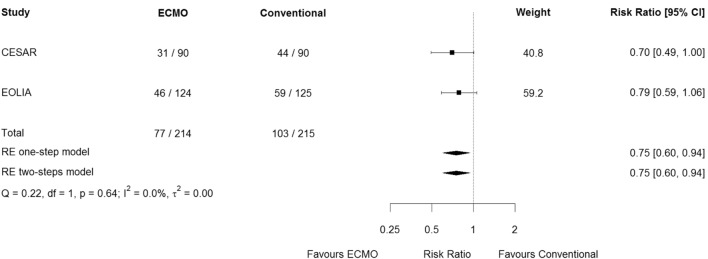

By day 90, 77 (36%) ECMO-group and 103 (48%) control group patients had died (relative risk, 0.75, 95% confidence interval 0.6–0.94; p = 0.013) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Results were similar in the one-step and two-steps models. There was no evidence of heterogeneity across studies (p = 0.64, I2 = 0%, τ2 = 0.000).

Table 2.

Endpoints

| Endpoint | ECMO group (N = 214) | Control group (N = 215) | Relative Risk or difference (95% CI) | p value | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | |||||

| Day 90 mortality—no. (%) | 77 (36) | 103 (48) | 0.75 (0.6–0.94) | 0.013 | 0 |

| Secondary endpointsa | |||||

| Day 90 treatment failure—no. (%) | 77 (36) | 119 (55) | 0.65 (0.52–0.8) | 0 | |

| Day 28 mortality—no. (%) | 50 (23) | 88 (41) | 0.57 (0.4–0.81) | 33 | |

| Day 60 mortality—no. (%) | 73 (34) | 101 (47) | 0.73 (0.58–0.92) | 0 | |

| Day 1–90 ICU-free daysb | 36 ± 32 | 28 ± 33 | 8 (2–14) | 0 | |

| Day 1–90 hospital-free daysb | 22 ± 27 | 18 ± 27 | 4 (− 1–9) | 0 | |

| Day 1–90 ventilation-free daysb | 40 ± 35 | 31 ± 34 | 8 (2–15) | 0 | |

| Day 1–60 vasopressor-free daysb,c | 35 ± 26 | 28 ± 27 | 8 (3–13) | 0 | |

| Day 1–60 RRT-free daysb,c | 35 ± 27 | 28 ± 27 | 7 (2–13) | 0 | |

| Day 1–60 neurological failure-free daysb,c,d | 38 ± 28 | 31 ± 30 | 7 (2–13) | 6 | |

Data are mean (SD) or number (%)

ECMO denotes extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ICU intensive care unit and RRT renal replacement therapy

aThe width of confidence intervals have not been adjusted for multiplicity and should not be used to infer definitive treatment differences

bFree-days were calculated assigning zero free-days to patients who died during the follow-up period

cDay-by-day follow-up was limited to Day 60 in the EOLIA trial

dNeurological failure was defined by the number of days without neurological depression requiring system monitoring/support' in CESAR study and the neurologic component of the sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score greater than 2

Fig. 1.

Forest plot of 90-day mortality in the intention-to-treat population

Secondary outcomes

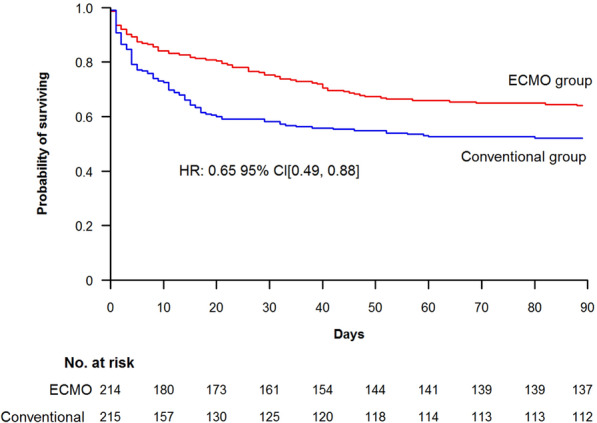

The hazard ratio for death within 90 days after randomisation in the ECMO group, as compared with the control group, was 0.65 (95% CI 0.49–0.88) (Fig. 2). The relative risk of treatment failure, defined as death by day 90 for the ECMO-group and death or crossover to ECMO for the control group was 0.65 (0.52–0.8) (Table 2 and eFig. 3 in the Supplement). At 90 days, ECMO-group patients had more days alive without ventilation (40 vs 31 days, mean difference, 8 days; 95% CI 2–15) and out of the ICU (36 vs 28 days, mean difference, 8 days; 95% CI 2–14) than those in the control group (Table 2 and eFig. 4 in the Supplement).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates in the intention-to-treat population of the time to death within the first 90 study days

At day 60 post-randomisation (90-day follow-up was not available for the following outcomes in EOLIA), patients in the ECMO group had more days alive without vasopressors (35 vs 28 days, mean difference, 8 days; 95% CI, 3 to 13), renal replacement therapy (35 vs 28 days, mean difference, 7 days; 95% CI 2–13) and neurological failure (38 vs 31 days, mean difference, 7 days; 95% CI 2–13) than those in the control group (Table 2 and eFig. 5 in the Supplement). Prone positioning and low-volume low-pressure mechanical ventilation were applied to 71% and 85% of control group patients, respectively (Table 3). Multiorgan failure and respiratory failure were the main causes of death in both groups (Table 3), while a cannulation-related fatal complication occurred in 3 of the 225 patients who received ECMO. Of the 214 patients randomised to ECMO, 7 (3%) died before ECMO could be established. Additional data on secondary outcomes are provided in Tables 2 and 3 and eFig. 6 in the Supplement.

Table 3.

Patients’ management and other outcomes

| Endpoint | ECMO group (N = 214) | Control group (N = 215) |

|---|---|---|

| Received ECMO—no. (%) | 189 (88) | 36 (17) |

| Days under ECMOa | 14.3 ± 12.6 | 16.6 ± 15 |

| Received LVLP MV—no. (%)b | 205 (98) | 181 (85) |

| Prone position (before and after randomisation)—no. (%)b | 114 (54) | 151 (71) |

| iNO or prostacyclin—no. (%)b | 84 (40) | 110 (51) |

| Renal replacement therapy—no. (%)b | 106 (50) | 129 (60) |

| Steroids—no. (%)b | 156 (74) | 140 (65) |

| ICU length of stay, days | 29.7 ± 24.6 | 23.6 ± 35.9 |

| For survivors | 35.2 ± 22.5 | 39.5 ± 26.3 |

| For non-survivors | 20.2 ± 17.6 | 15.4 ± 16.2 |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 49 ± 43.1 | 42.7 ± 69.3 |

| For survivors | 58.3 ± 23.8 | 60 ± 28.5 |

| For non-survivors | 20.2 ± 17.6 | 15.4 ± 16.2 |

| Cause of death | ||

| Respiratory failure | 13 (6) | 36 (17) |

| Multiple organ failure | 35 (16) | 44 (20) |

| ECMO cannulation-related | 2 (1) | 1 (0) |

| Miscellaneous | 27 (13) | 22 (10) |

Data are mean (SD) or number (%); see eTable 5 in the Supplement for missing data

ECMO denotes extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, LVLP MV, low-volume low-pressure mechanical ventilation, iNO inhaled nitric oxide, and ICU intensive care unit

Missing data were < 2.5% for patients’ outcomes (see eTable 5 in the Supplement)

aFor patients who received ECMO

bFrom randomisation to day 60

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

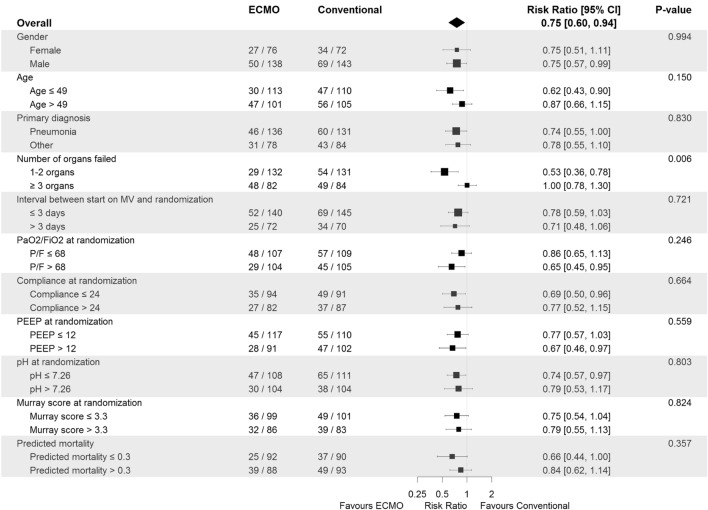

The relative risks of death at day 90 post-randomisation according to the per-protocol and as-treated analyses were 0.75 (95% CI 0.6–0.94) and 0.86 (95% CI 0.68–1.09), respectively (eFig. 7 in the Supplement). The only significant treatment-covariate interaction identified in subgroup analyses was the number of organs failing at randomisation with RR = 0.53 (95% CI 0.36–0.78) among patients with 1–2 organ failures and RR = 1.00 (95% CI 0.78–1.3) among patients with 3 or more organ failures, p = 0.006 for interaction (Fig. 3). There was no evidence to suggest a differential treatment effect for any other subgroups.

Fig. 3.

Subgroup analyses for the primary outcome according to baseline characteristics. MV, mechanical ventilation; number of organ failed (0–6) defined as the corresponding component sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score > 2; APACHE2 (CESAR) and SAPS2 (EOLIA) scores were both translated to predicted probability of ICU mortality

Quality of evidence

The Summary Of Findings Table reporting the evaluation of the quality of evidence for the seven most important outcomes is presented in eTable 6 in the Supplement. The level of evidence was high for mortality at 90 days, time to death and treatment failure.

Discussion

In this individual patient data meta-analysis of patients with severe ARDS included in the CESAR [15] and EOLIA [17] randomised trials, there is strong evidence to suggest that early recourse to ECMO leads to a reduction in 90-day mortality and less treatment failure compared with conventional ventilatory support. Patients randomised to ECMO also had more days alive out of the ICU and without respiratory, cardiovascular, renal and neurological failure.

The benefit of ECMO in severe ARDS patients has long been debated [24–27]. Because of highly challenging design and conduct issues, only four randomised trials of extracorporeal life support for adult patients with acute respiratory failure have been performed in the last 5 decades [15, 17, 28, 29]. Our meta-analysis included only the two most recent trials (CESAR [15] and EOLIA [17]) since major advances in ICU care and in ECMO techniques have occurred in the past 15 years making the two older trials not relevant for comparison [10, 20, 21]. In addition the two older trials did not use venovenous ECMO. One used venoarterial ECMO [28] and one used low-flow veno-venous extracorporeal CO2 removal [29]. Characteristics of patients included in EOLIA and CESAR were comparable regarding ARDS aetiology and disease severity at randomisation. Patients were enrolled early after the initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation and rates of control patients being proned and receiving low-volume low-pressure mechanical ventilation were high. Both EOLIA and CESAR trials showed a comparable survival benefit with ECMO, but neither was individually powered to detect a reasonable survival difference between groups. Specifically, the data safety monitoring board of EOLIA, following pre-specified guidance using a sequential design with a two-sided triangular test based on 60-day mortality, recommended stopping the trial for futility after 75% of the maximal sample size had been enrolled, because the probability of demonstrating a 20% absolute risk reduction in mortality with ECMO was considered unlikely. Our meta-analysis, which includes a much larger number of patients and shows higher survival with ECMO in both the intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses provides strong evidence about the benefit of ECMO in severe ARDS. Our results also extend the conclusions of a post-hoc Bayesian analysis of EOLIA indicating a very high probability of ECMO success in severe ARDS patients, ranging from 88 to 99% depending on the chosen priors [30]. Our results are consistent with two previous aggregated data meta-analyses in the field: one was a network meta-analysis considering different interventions whose impact is limited by the lack of direct comparisons [31] and the other focused on ECMO [32]. Our IPD meta-analyses goes beyond these two previous studies and provides a stronger evidence on the benefit of ECMO in ARDS for the following reasons. IPD meta-analyses provides a higher level of evidence than aggregated data meta-analyses, because they are independent of the quality of reporting in included studies and allow evaluation of other important outcomes such as time to death and number of days without organ failures [33, 34].

In this study, we showed that, beyond mortality, duration and severity of organ failures also favoured ECMO, and these results were highly consistent between the two studies. This observation provides insights into the potential pathophysiological mechanisms of ECMO-associated benefits in severe ARDS [10]. Although extracorporeal gas exchange may rescue some patients dying of profound hypoxemia or in whom high pressure mechanical ventilation has become dangerous, minimization of lung stress and strain associated with positive pressure ventilation may drive most of the improved outcomes observed under ECMO [10]. Ultraprotective ventilation with very low VTs, driving pressures and respiratory rates [35], and, therefore, minimized overall mechanical power transmitted to lung alveoli [36] may reduce ventilator-induced lung injury, pulmonary and systemic inflammation and ultimately organ failure leading to death. These data also reinforce the recent recommendation of the World Health Organization (WHO) [37], and the Surviving Sepsis Campaign [38] to consider ECMO support in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related ARDS with refractory hypoxemia if lung protective mechanical ventilation was insufficient to support the patient [39].

Meta-analyses of individual patient data can also explore outcomes in important subgroups and suggest which population may derive the greatest benefit of a specific intervention, which is very limited in aggregated data meta-analyses [40]. In this study, the mortality of patients with only one or two organs failing at randomisation was almost halved with ECMO (22% vs. 41%), while it was not substantially different between groups in patients with ≥ 3 organ failures. This finding suggests that veno-venous ECMO may not be able to improve the outcomes of ARDS patients with severe shock and multiple organ failure. In EOLIA, patients with baseline PaO2/FiO2 > 66 mmHg or those enrolled due to severe respiratory acidosis and hypercapnia, seemed to derive the greatest benefit of ECMO [17].

This analysis has several limitations. First, inclusion criteria were more stringent for the EOLIA trial, in which, for example, ventilator optimization (FiO2 > 80%, VT at 6 ml/kg predicted body weight and PEEP > 10 cm H2O) was mandatory before enrolment. However, it should be noted that baseline patient characteristics were comparable regarding ARDS severity at inclusion (eTable 4 in the Supplement). Second patient management was not similar in the two studies. In CESAR, 24% of patients randomised to the ECMO arm did not receive ECMO and there was no standardized protocol for mechanical ventilation in the control group. Conversely, in EOLIA, 98% of patients randomised to ECMO received the intervention, the mechanical ventilation strategy in the control group followed a strict protocol, and rescue ECMO was applied to 28% of control group patients who had developed refractory hypoxemia. However, this meta-analysis showed a significantly lower mortality with ECMO in the per-protocol analysis including only patients in whom ECMO had been initiated in the ECMO arm and patients not having ECMO in the control arm. This analysis minimizes the aforementioned management differences, since the least severe patients who did not receive ECMO after MV optimization in CESAR were excluded from the ECMO arm and the most severe patients who needed rescue ECMO in EOLIA were excluded from the control arm. In contrast, ECMO was not associated with a mortality benefit in the as-treated population, but such an analysis strongly disadvantages the ECMO group, which includes the most severe control patients rescued by ECMO. Second, this meta-analysis does not provide detailed data on ECMO-related safety endpoints, since they were not reported in CESAR. Death directly related to ECMO cannulation was rare in both studies and the rates of stroke and major bleeding were also low in EOLIA, in which a restrictive anticoagulation strategy was applied [17]. Third, no long-term outcomes beyond 90 day post-randomisation were analysed although the CESAR trial [15] and a retrospective cohort of ARDS patients [41] reported satisfactory long-term health-related quality-of-life after ECMO. Fourth, only the CESAR trial provided a cost-effectiveness analysis that suggested a benefit of the transfer of ARDS patients to a centre with an ECMO-based management protocol [15]. Our results, showing improved survival, with more days alive out of the ICU and without the need for major organ support are in line with CESAR’s cost-effectiveness data. Fifth, many conditions such as MV duration > 7 days prior to ECMO or major comorbidities were exclusion criteria for enrolment in both CESAR and EOLIA. The indication to initiate ECMO should, therefore, be carefully evaluated in these situations. Lastly, ECMO should be used in experienced centres and only after proven conventional management of severe ARDS (including lung protective mechanical ventilation and prone positioning) have been applied and failed [42], except when hypoxemia is immediately life-threatening, or when the patient is too unstable for prone positioning [43].

In conclusion, this meta-analysis of individual patient data of the CESAR and EOLIA trials showed strong evidence of a clinically meaningful benefit of early ECMO in severe ARDS patients. Another large study of ECMO appears unlikely in this setting and future research should focus on the identification of patients most likely to benefit from ECMO and optimization of treatment strategies after ECMO initiation [44].

The study was supported by the Direction de la Recherche Clinique et de l’Innovation (DRCI), Assistance Publique—Hopitaux de Paris (APHP), with a grant from the French Ministry of Health (CRC 2018, #18,021).

The EOLIA trial was supported by the Direction de la Recherche Clinique et du Développement (DRCD), Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris (APHP), with a grant from the French Ministry of Health (Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique number, PHRC 2009 081,224), the EOLIA Trial Group, the Réseau Européen en Ventilation Artificielle (REVA) and the International ECMO Network (ECMONet, https://www.internationalecmonetwork.org).

The CESAR trial was supported by the UK NHS Health Technology Assessment, English National Specialist Commissioning Advisory Group, Scottish Department of Health, and Welsh Department of Health.

See the Supplement for the list of EOLIA and CESAR collaborators.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs Elizabeth Allen for her help in preparing the data of the CESAR trial.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

Alain Combes reports grants from Getinge, personal fees from Getinge, Baxter and Xenios outside the submitted work. Matthieu Schmidt reports lecture fees from Getinge, Drager and Xenios outside the submitted work. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the purpose of this manuscript. The study protocol for the systematic review and IPD meta-analysis was approved by the relevant independent ethics committees: in France, Comité de Protection des Personnes CPP Ile de France VI, Pitié-Salpêtrière, on 04/19/2018, Ref #12 and in the UK by the Ethics committee of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, on 04/12/2019, LSHTM Ethics Ref: 17159. Only patient characteristics and outcomes already evaluated in the trials were combined in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, Wheeler A. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briel M, Meade M, Mercat A, Brower RG, Talmor D, Walter SD, Slutsky AS, Pullenayegum E, Zhou Q, Cook D, Brochard L, Richard JC, Lamontagne F, Bhatnagar N, Stewart TE, Guyatt G. Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:865–873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franchineau G, Brechot N, Lebreton G, Hekimian G, Nieszkowska A, Trouillet JL, Leprince P, Chastre J, Luyt CE, Combes A, Schmidt M. Bedside contribution of electrical impedance tomography to setting positive end-expiratory pressure for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-treated patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:447–457. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1055OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papazian L, Forel JM, Gacouin A, Penot-Ragon C, Perrin G, Loundou A, Jaber S, Arnal JM, Perez D, Seghboyan JM, Constantin JM, Courant P, Lefrant JY, Guerin C, Prat G, Morange S, Roch A. Neuromuscular blockers in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1107–1116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guerin C, Reignier J, Richard JC, Beuret P, Gacouin A, Boulain T, Mercier E, Badet M, Mercat A, Baudin O, Clavel M, Chatellier D, Jaber S, Rosselli S, Mancebo J, Sirodot M, Hilbert G, Bengler C, Richecoeur J, Gainnier M, Bayle F, Bourdin G, Leray V, Girard R, Baboi L, Ayzac L. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2159–2168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, van Haren F, Larsson A, McAuley DF, Ranieri M, Rubenfeld G, Thompson BT, Wrigge H, Slutsky AS, Pesenti A. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315:788–800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, Jacobson SD, Meyer BJ, Balough EM, Aaron JG, Claassen J, Rabbani LE, Hastie J, Hochman BR, Salazar-Schicchi J, Yip NH, Brodie D, O'Donnell MR. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763–1770. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, Wu Y, Zhang L, Yu Z, Fang M, Yu T, Wang Y, Pan S, Zou X, Yuan S, Shang Y. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respiratory Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodie D, Slutsky AS, Combes A. Extracorporeal life support for adults with respiratory failure and related indications: a review. JAMA. 2019;322:557–568. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt M, Pham T, Arcadipane A, Agerstrand C, Ohshimo S, Pellegrino V, Vuylsteke A, Guervilly C, McGuinness S, Pierard S, Breeding J, Stewart C, Ching SSW, Camuso JM, Stephens RS, King B, Herr D, Schultz MJ, Neuville M, Zogheib E, Mira JP, Roze H, Pierrot M, Tobin A, Hodgson C, Chevret S, Brodie D, Combes A. Mechanical ventilation management during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. an international multicenter prospective cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:1002–1012. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201806-1094OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pham T, Combes A, Roze H, Chevret S, Mercat A, Roch A, Mourvillier B, Ara-Somohano C, Bastien O, Zogheib E, Clavel M, Constan A, Marie Richard JC, Brun-Buisson C, Brochard L. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for pandemic influenza A(H1N1)-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome: a cohort study and propensity-matched analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:276–285. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201205-0815OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies A, Jones D, Bailey M, Beca J, Bellomo R, Blackwell N, Forrest P, Gattas D, Granger E, Herkes R, Jackson A, McGuinness S, Nair P, Pellegrino V, Pettila V, Plunkett B, Pye R, Torzillo P, Webb S, Wilson M, Ziegenfuss M. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for 2009 influenza A(H1N1) acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA. 2009;302:1888–1895. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noah MA, Peek GJ, Finney SJ, Griffiths MJ, Harrison DA, Grieve R, Sadique MZ, Sekhon JS, McAuley DF, Firmin RK, Harvey C, Cordingley JJ, Price S, Vuylsteke A, Jenkins DP, Noble DW, Bloomfield R, Walsh TS, Perkins GD, Menon D, Taylor BL, Rowan KM. Referral to an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation center and mortality among patients with severe 2009 influenza A(H1N1) JAMA. 2011;306:1659–1668. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, Wilson A, Allen E, Thalanany MM, Hibbert CL, Truesdale A, Clemens F, Cooper N, Firmin RK, Elbourne D. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1351–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peek GJ, Elbourne D, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, Wilson A, Allen E, Clemens F, Firmin R, Hardy P, Hibbert C, Jones N, Killer H, Thalanany M, Truesdale A. Randomised controlled trial and parallel economic evaluation of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR) Health Technol Assessment (Winchester, England) 2010;14:1–46. doi: 10.3310/hta14350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, Demoule A, Lavoue S, Guervilly C, Da Silva D, Zafrani L, Tirot P, Veber B, Maury E, Levy B, Cohen Y, Richard C, Kalfon P, Bouadma L, Mehdaoui H, Beduneau G, Lebreton G, Brochard L, Ferguson ND, Fan E, Slutsky AS, Brodie D, Mercat A. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965–1975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R. The American-European consensus conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Combes A, Brodie D, Bartlett R, Brochard L, Brower R, Conrad S, De Backer D, Fan E, Ferguson N, Fortenberry J, Fraser J, Gattinoni L, Lynch W, MacLaren G, Mercat A, Mueller T, Ogino M, Peek G, Pellegrino V, Pesenti A, Ranieri M, Slutsky A, Vuylsteke A. Position paper for the organization of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation programs for acute respiratory failure in adult patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:488–496. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201404-0630CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Combes A, Pesenti A, Ranieri VM. Fifty years of research in ARDS. Is extracorporeal circulation the future of acute respiratory distress syndrome management? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1161–1170. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0217CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernan MA, Hopewell S, Hrobjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Juni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Clarke M (2019) Chapter 26: Individual participant data. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6–0 (updated July 2019) Cochrane, www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- 24.Li X, Scales DC, Kavanagh BP. Unproven and expensive before proven and cheap: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation versus prone position in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:991–993. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2216CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt M, Combes A, Shekar K. ECMO for immunosuppressed patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: drawing a line in the sand. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:1140–1142. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05632-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernando SM, Qureshi D, Tanuseputro P, Fan E, Munshi L, Rochwerg B, Talarico R, Scales DC, Brodie D, Dhanani S, Guerguerian AM, Shemie SD, Thavorn K, Kyeremanteng K. Mortality and costs following extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in critically ill adults: a population-based cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:1580–1589. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05766-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan E, Karagiannidis C. Less is more: not (always) simple-the case of extracorporeal devices in critical care. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:1451–1453. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05726-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zapol WM, Snider MT, Hill JD, Fallat RJ, Bartlett RH, Edmunds LH, Morris AH, Peirce EC, 2nd, Thomas AN, Proctor HJ, Drinker PA, Pratt PC, Bagniewski A, Miller RG., Jr Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in severe acute respiratory failure. A randomized prospective study JAMA. 1979;242:2193–2196. doi: 10.1001/jama.242.20.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris AH, Wallace CJ, Menlove RL, Clemmer TP, Orme JF, Jr, Weaver LK, Dean NC, Thomas F, East TD, Pace NL, et al. Randomized clinical trial of pressure-controlled inverse ratio ventilation and extracorporeal CO2 removal for adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:295–305. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.2.8306022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goligher EC, Tomlinson G, Hajage D, Wijeysundera DN, Fan E, Juni P, Brodie D, Slutsky AS, Combes A. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and posterior probability of mortality benefit in a post hoc bayesian analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:2251–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aoyama H, Uchida K, Aoyama K, Pechlivanoglou P, Englesakis M, Yamada Y, Fan E. Assessment of therapeutic interventions and lung protective ventilation in patients with moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA network open. 2019;2:e198116. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munshi L, Walkey A, Goligher E, Pham T, Uleryk EM, Fan E. Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Respiratory medicine. 2019;7:163–172. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tierney JF, Vale C, Riley R, Smith CT, Stewart L, Clarke M, Rovers M. Individual participant data (IPD) meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: guidance on their use. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tierney JF, Fisher DJ, Burdett S, Stewart LA, Parmar MKB. Comparison of aggregate and individual participant data approaches to meta-analysis of randomised trials: an observational study. PLoS Med. 2020;17:e1003019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abrams D, Schmidt M, Pham T, Beitler JR, Fan E, Goligher EC, McNamee JJ, Patroniti N, Wilcox ME, Combes A, Ferguson ND, McAuley DF, Pesenti A, Quintel M, Fraser J, Hodgson CL, Hough CL, Mercat A, Mueller T, Pellegrino V, Ranieri VM, Rowan K, Shekar K, Brochard L, Brodie D. Mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome during extracorporeal life support. research and practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:514–525. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201907-1283CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serpa Neto A, Deliberato RO, Johnson AEW, Bos LD, Amorim P, Pereira SM, Cazati DC, Cordioli RL, Correa TD, Pollard TJ, Schettino GPP, Timenetsky KT, Celi LA, Pelosi P, Gama de Abreu M, Schultz MJ. Mechanical power of ventilation is associated with mortality in critically ill patients: an analysis of patients in two observational cohorts. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1914–1922. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization: Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when COVID-19 disease is suspected. Last accessed July, 10 2020: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/clinical-management-of-covid-19

- 38.Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E, Oczkowski S, Levy MM, Derde L, Dzierba A, Du B, Aboodi M, Wunsch H, Cecconi M, Koh Y, Chertow DS, Maitland K, Alshamsi F, Belley-Cote E, Greco M, Laundy M, Morgan JS, Kesecioglu J, McGeer A, Mermel L, Mammen MJ, Alexander PE, Arrington A, Centofanti JE, Citerio G, Baw B, Memish ZA, Hammond N, Hayden FG, Evans L, Rhodes A. Surviving sepsis campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:854–887. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt M, Hajage D, Lebreton G, Monsel A, Voiriot G, Levy D, Baron E, Beurton A, Chommeloux J, Meng P, Nemlaghi S, Bay P, Leprince P, Demoule A, Guidet B, Constantin JM, Fartoukh M, Dres M, Combes A. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome associated with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respiratory Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30328-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fisher DJ, Carpenter JR, Morris TP, Freeman SC, Tierney JF. Meta-analytical methods to identify who benefits most from treatments: daft, deluded, or deft approach? BMJ. 2017;356:j573. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt M, Zogheib E, Roze H, Repesse X, Lebreton G, Luyt CE, Trouillet JL, Brechot N, Nieszkowska A, Dupont H, Ouattara A, Leprince P, Chastre J, Combes A. The PRESERVE mortality risk score and analysis of long-term outcomes after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1704–1713. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3037-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abrams D, Ferguson ND, Brochard L, Fan E, Mercat A, Combes A, Pellegrino V, Schmidt M, Slutsky AS, Brodie D. ECMO for ARDS: from salvage to standard of care? Lancet Respiratory Med. 2019;7:108–110. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30506-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacLaren G, Combes A, Brodie D. Saying no until the moment is right: initiating ECMO in the EOLIA era. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guervilly C, Prud'homme E, Pauly V, Bourenne J, Hraiech S, Daviet F, Adda M, Coiffard B, Forel JM, Roch A, Persico N, Papazian L. Prone positioning and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: time for a randomized trial? Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:1040–1042. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05570-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.