Abstract

Introduction

When the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic reached Europe in 2020, a German governmental order forced clinics to immediately suspend elective care, causing a problem for patients with chronic illnesses such as epilepsy. Here, we report the experience of one clinic that converted its outpatient care from personal appointments to telemedicine services.

Methods

Documentations of telephone contacts and telemedicine consultations at the Epilepsy Center Frankfurt Rhine-Main were recorded in detail between March and May 2020 and analyzed for acceptance, feasibility, and satisfaction of the conversion from personal to telemedicine appointments from both patients' and medical professionals' perspectives.

Results

Telephone contacts for 272 patients (mean age: 38.7 years, range: 17–79 years, 55.5% female) were analyzed. Patient-rated medical needs were either very urgent (6.6%, n = 18), urgent (23.5%, n = 64), less urgent (29.8%, n = 81), or nonurgent (39.3%, n = 107). Outpatient service cancelations resulted in a lack of understanding (9.6%, n = 26) or anger and aggression (2.9%, n = 8) in a minority of patients, while 88.6% (n = 241) reacted with understanding, or relief (3.3%, n = 9). Telemedicine consultations rather than a postponed face-to-face visit were requested by 109 patients (40.1%), and these requests were significantly associated with subjective threat by SARS-CoV-2 (p = 0.004), urgent or very urgent medical needs (p = 0.004), and female gender (p = 0.024). Telemedicine satisfaction by patients and physicians was high. Overall, 9.2% (n = 10) of patients reported general supply problems due to SARS-CoV-2, and 28.4% (n = 31) reported epilepsy-specific problems, most frequently related to prescriptions, or supply problems for antiseizure drugs (ASDs; 22.9%, n = 25).

Conclusion

Understanding and acceptance of elective ambulatory visit cancelations and the conversion to telemedicine consultations was high during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown. Patients who engaged in telemedicine consultations were highly satisfied, supporting the feasibility and potential of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

Keywords: COVID, Corona, Pandemic, Seizure, Anticonvulsant

Highlights

-

•

Health care systems worldwide had to face reorganization during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic

-

•

Acceptance of the SARS-CoV-2-related conversion to telemedicine services was high

-

•

Urgent concerns, perception of SARS-CoV-2-associated threats, and female gender were associated with use of telemedicine

-

•

Patient and physician satisfaction with telemedicine services was high

-

•

Supply problems severely affected epilepsy patients during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic

1. Introduction

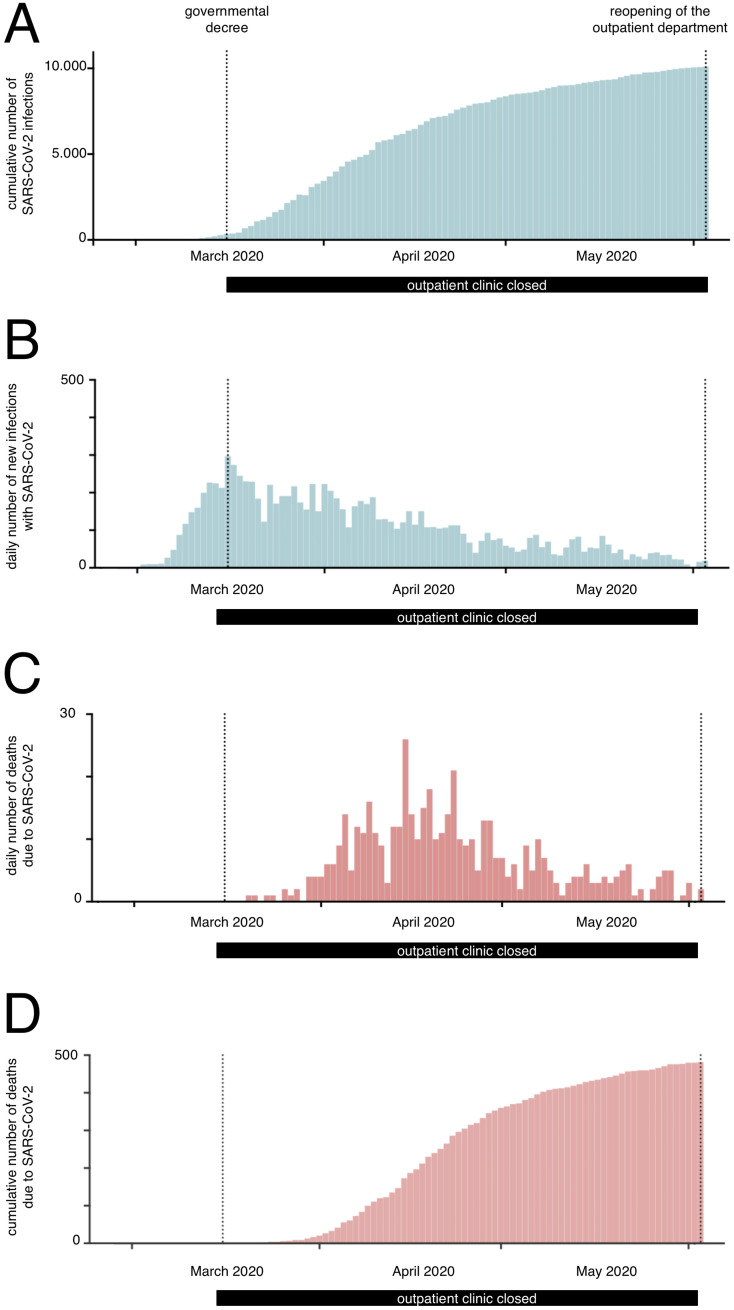

During the rapid pandemic spread from its assumed origin in Wuhan, China around the world, the new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and its clinical manifestation as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) reached Germany in the first quarter of 2020 [1,2]. At that time, the known number of infected patients worldwide was in the hundreds of thousands, a high percentage of which had severe courses of disease, with many patients hospitalized and deceased in China and Italy [3]. On March 16, 2020, the German Ministry of Health, and the health authorities of the 16 German states, released an order obliging all hospitals and clinics to shut down their elective ambulatory and inpatient care services immediately to prepare for the anticipated increased need for emergency care, isolation, and intensive care capacity [4]; the time course of the pandemic in Hessen is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Time course of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Hessen, from March 2 to June 2, 2020, showing the cumulative (A) and daily number (B) of confirmed cases, as well as the daily (C) and cumulative (D) number of COVID-19 associated deaths (status as of June 4, 2020, based on the official Robert Koch-Institut [RKI, Berlin, Germany] dataset, www.rki.de).

The German healthcare system is based on a broad supply of general practitioners as well as on specialist medical practitioners, e.g., neurologists in private practice [5,6]. The third level of outpatient medical care is provided by specialized hospital outpatient clinics, e.g., specialized epilepsy centers, serving as a main supplier for severely ill patients. Based on the extremely subdivided and specialized medical care system in Germany, many patients who relied on additional care by specialized hospital outpatient clinics were greatly affected by the government's order. As a direct consequence of the statutory decree, ambulatory care options especially for patients with chronic illness decreased dramatically.

Epilepsy is one of the most frequent chronic neurological diseases, characterized by paroxysmal and mostly unpredictable seizures, affecting more than 700,000 patients of every age in Germany with a prevalence between 0.6% and 0.8% [5,7,8]. In spite of excellent medical treatment, approximately one-third of these patients have refractory disease and are therefore often seen in outpatient departments at specialized epilepsy centers or hospitals on a regular basis [9,10]. Patients with high seizure frequencies, frequent generalized tonic–clonic seizures, those participating in ongoing pharmacological studies, those with therapeutic neuromodulation devices (e.g., vagal nerve stimulation (VNS)), and those with potentially surgically treatable focal epilepsy continued to rely on specialized epilepsy care, which has been shown to be associated with a reduction in mortality within this cohort [11,12]. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the influence on patients with epilepsy was unknown, and a recent study points toward a higher cumulative incidence in patients with active epilepsy and increased fatality in patients with hypertension and epilepsy [13]. To maintain at least a minimal version of specialized medical care for these often severely affected patients, many specialized departments in Germany, and all over the world, tried to rapidly convert face-to-face contacts during personal clinic appointments to telemedicine consultations by telephone or video-telephone [14,15]. Evaluation of theses fundamental changes in outpatient medical care is indispensable in measuring the performance and flexibility of medical systems on the one hand as well as improving patient care in potentially upcoming pandemics or crisis, on the other.

The aim of this study was to analyze the acceptance, feasibility, and satisfaction of the SARS-CoV-2-related conversion from face-to-face to telemedicine appointments from the perspectives of both patients and medical professionals. In addition, different sociodemographic, disease-specific, and SARS-CoV-2-associated aspects were assessed regarding acceptance of telemedicine services.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients, study setting, and design

The Epilepsy Center Frankfurt Rhine-Main at the University Hospital Frankfurt (Germany) is a tertiary care center for patients with epilepsy of all ages, performs presurgical evaluations for drug-refractory epilepsies, and includes a large epilepsy outpatient clinic with about 2500 patient-contacts per year [11]. The University Hospital Frankfurt provides inpatient care for over 50,000 patients, and ambulatory care for over 450,000 patients, annually.

On March 16, 2020, a governmental decree [4] against the spread of SARS-CoV-2 resulted in the cessation of elective outpatient treatments with the consequence that all outpatient visits had to be canceled. Telemedicine consultations in the sense of a telephone contact were offered to all patients with canceled personal appointments. The option of contacts via video telephony or internet-based video chats was not possible due to the lack of lead time and German data protection guidelines. Patients who accepted a telemedicine consultation were contacted by telephone on the day of their original appointment at a prearranged time by an experienced doctor's receptionists. Patients with life-threatening conditions, or those requiring immediate medical care or advice, were contacted rapidly or seen in the emergency department while meeting strict local hygienic requirements due to SARS-CoV-2, and were not included in this study. All telephone-contact appointments, as well as later telemedicine consultations, were documented by detailed protocol from March 17, 2020 [4] until May 29, 2020 during the lockdown of the outpatient department. All telemedicine consultations were performed by experienced residents or specialists from the Epilepsy Center Frankfurt Rhine-Maine with a supervision from a senior physician being available at all times. Documentation focused on acceptance, feasibility, and satisfaction of the rapid conversion from face-to-face to telemedicine appointments from both patients' and medical professionals' perspectives, and on SARS-CoV-2-related aspects. Data regarding sociodemographic and epilepsy characteristics were retrieved from patient files for a retrospective exploratory analysis that was approved by the local ethics committee of the Goethe-University Frankfurt (Ref. 20-747). Strengthening The Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines and REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected Data (RECORD) guidelines were closely followed to improve the study design and reporting [16,17]. Seizure and epilepsy syndrome classifications used included the 2017 versions from the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) [[18], [19], [20]] and the Integrated Epilepsy Classification published in 2020 [21]. Patients' acceptance, urgency of the appointment, satisfaction, reaction, and subjective thread for SARS-CoV-2 were accessed using an anchored scale with 4–5 items. Physicians' satisfaction and assessment of urgency was directly accessed after the phone call.

2.2. Data analysis, data representation, and reporting

Data collection was performed using Microsoft Excel Version 16 (Microsoft Corp., Albuquerque, US) using a double-entry procedure to minimize entry errors. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, US). For descriptive categorical variables, percentages and frequencies were used; for descriptive cardinal variables, means and standard deviations (SDs) or medians and ranges were used, as appropriate. All numbers, except p-values, were rounded to the first decimal place. Statistical comparisons were conducted using Pearson's chi-squared test. In cases with fewer than 60 subjects, Pearson's chi-squared test with a Yates correction was performed. p-values < 0.05 were considered significant. Corrections for multiple testing was performed using the well-established Benjamini–Hochberg procedure based on false-discovery rates [22].

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and disease-specific characteristics of the cohort

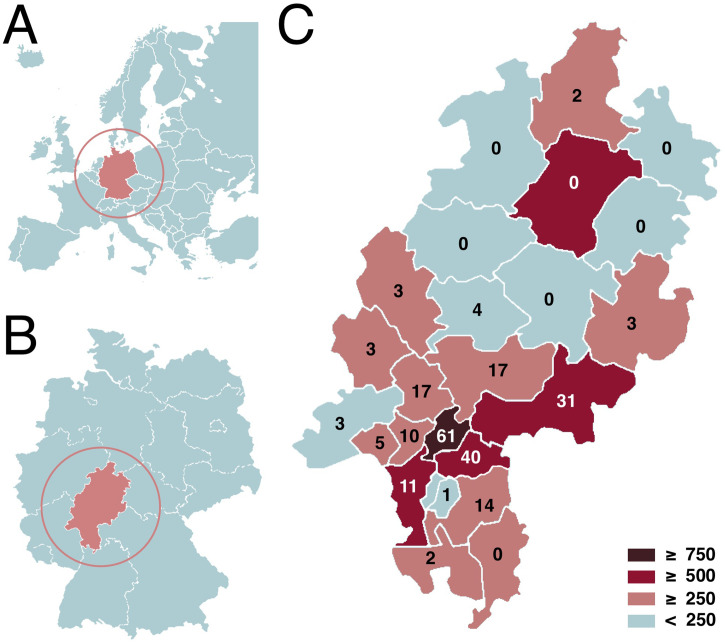

A total of 272 patients were enrolled in this study, i.e., all patients that had an already scheduled outpatient visit between March 17, 2020 and May 29, 2020 that did not require immediate care (2 patients were excluded and immediately seen at the ER). The mean age was 38.7 years (SD ± 14.5 years, median: 36.0 years, range: 17–79 years), gender distribution was 55.5% female (n = 151) and 44.5% male (n = 121) among participants (Table 1 ). The geographical distribution of patients and distribution of confirmed COVID-19 cases is shown in Fig. 2 . Most patients had focal epilepsy (63.4%, n = 174), followed by patients with unknown (19.1%, n = 52), generalized (16.2%, n = 44), or combined epilepsy (0.7%, n = 2). Regarding seizure types, most patients reported only focal seizures with or without impaired awareness (22.1%, n = 60), followed by focal to bilateral convulsive seizures (58.8%, n = 160), only generalized convulsive seizures (16.5%, n = 45), and unknown or other seizure types (19.1%, n = 52). Overall, 76.1% of the enrolled subjects had active epilepsy with ongoing seizures during the previous 12 months, while 19.5% of the patients had epilepsy in remission, with complete seizure freedom for more than 12 months. In 4.4% (n = 12) of the study population, there were insufficient data available for recent seizure frequency.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and telemedicine-related aspects of the cohort (n = 272).

| % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic aspects | |

| Gender | Female 55.5 (151) Male 45.5 (121) |

| Age | Mean ± SD 38.7 ± 14.5 years Median: 35 years Range: 17–79 years |

| Number of postponement contacts by telephone | |

| Total number of contacts | 100.0 (278) |

| Single contacts | 98.1 (272) |

| Repeated contacts | 1.9 (6) |

| Change in appointment modality | |

| Patients switched to telemedicine care | 40.1 (109) |

| Patients switched to a later appointment | 61.4 (167) |

| Patients insisting on an urgent appointment | 0.4 (1) |

| Patients refusing a reassessment in general | 0.4 (1) |

| Reaction to canceling of the personal appointment | |

| Angry, upset | 2.9 (8) |

| Lack of understanding | 9.6 (26) |

| Understanding | 88.6 (241) |

| Relief, welcoming the decision | 3.3 (9) |

| Urgency of the appointment from a patient view | |

| Very urgent | 6.6 (18) |

| Urgent | 23.5 (64) |

| Less urgent | 29.8 (81) |

| Not urgent | 39.3 (107) |

| Not available | 2.9 (8) |

| Epilepsy type | |

| Focal epilepsy | 63.4 (174) |

| Generalized epilepsy | 16.2 (44) |

| Focal + generalized epilepsy | 0.7 (2) |

| Other and unknown | 19.1 (52) |

| Seizure types | |

| Focal seizures with or without impaired awareness | 22.1 (60) |

| Focal and focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures | 58.8 (160) |

| Generalized convulsive seizures | 16.5 (45) |

| Other and unknown | 2.6 (7) |

| Severity of epilepsy | |

| Active epilepsy (ongoing seizures) | 76.1 (207) |

| Epilepsy in remission (seizure-free > 12 months) | 19.5 (53) |

| Insufficient data | 4.4 (12) |

| Subjective threat by SARS-CoV-2 from a patient view | |

| Very serious | 5.5 (15) |

| Serious | 35.7 (97) |

| Less serious | 37.5 (102) |

| None | 14.3 (39) |

| Not available | 9.2 (25) |

Fig. 2.

Geographical overview of Europe (A) and Germany (B) to help locating the Federal State of Hessen (darker area). (C) The inset numbers represent enrolled patients from the different administrative regions of Hessen. Using color grading (lower right), the total number of COVID-19 cases of the different administrative regions of Hesse are shown (status as of June 4, 2020, based on the official Robert Koch-Institut [RKI, Berlin, Germany] dataset (www.rki.de). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2. Initial phone contact

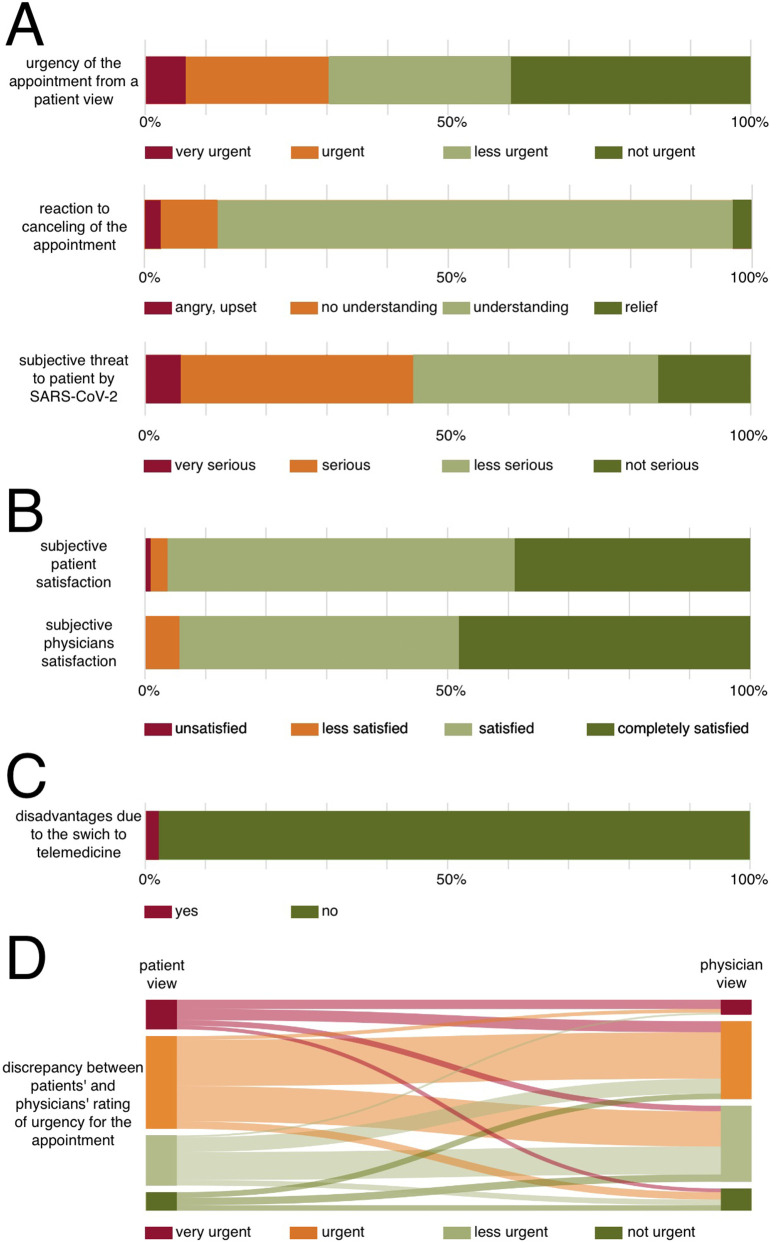

Overall, 272 initial phone calls were performed to cancel personal appointments and to schedule telemedicine services. Most patients (88.6%, n = 241) reacted with understanding and 3.3% (n = 9) with relief to cancelations of their outpatient appointments. Only a minority (9.6%, n = 26) showed lack of understanding, and 2.9% (n = 8) reacted with anger or aggression (Fig. 3A). Asked for the urgency of their disease-specific concerns, patients estimated appointment priorities as very urgent (6.6%, n = 18), urgent (23.5%, n = 64), less urgent (29.9%, n = 81), and not urgent (39.3%, n = 107). A total number of 109 patients (40.1%) requested telemedicine consultations, while 61.4% (n = 167) of subjects preferred to postpone visits, even if exact future rescheduling was unknown. One patient (0.4%) insisted on an urgent appointment because of an increased seizure frequency and seizure clusters, but failed to appear on the arranged day. The patient was seen later at the emergency department, electroencephalography (EEG) was performed and antiseizure drugs (ASDs) changed. He was discharged at the same day in improved health conditions. Another patient (0.4%) refused the postponement of the visit and was lost to further follow-up. The subjective personal threat from SARS-CoV-2 for patients and their families was categorized as very serious in 5.5% (n = 15) of subjects, serious in 25.7% (n = 97), less serious 37.5% (n = 102), nonexistent in 14.3% (n = 39), and no data were available for 9.2% (n = 25).

Fig. 3.

Likert scales for patient subjective urgency for canceled personal appointments, reactions to appointment cancelations, and subjective threat assessment of SARS-CoV-2 according to initial phone call notes (A, n = 272). In addition, patient and physician satisfaction with individual telemedical consultations (B, n = 109), and disadvantages of telemedicine compared with face-to-face appointments are shown for patients who accepted telemedicine consultations (C, n = 109). Discrepancies between patients' and physicians' rating of urgency for the appointment are displayed as Sankey diagram (D, n = 109).

3.3. Telemedicine outpatient consultations

A total of 109 telemedicine appointments were analyzed (Table 2 ). The geographical origins of patients are provided in the Supplementary Table 1. The most frequent reasons for seeking medical advice were general disease-specific questions and aspects (57.8%, n = 63) followed by concerns about side effects of ASDs (31.2%, n = 34), ongoing or planned changes in ASD regimens (29.4%, n = 32), increased seizure frequency (14.7%, n = 16), discussions of diagnostic findings and recommendations (14.7%, n = 16), ASD management during a planned, new or known pregnancy (each 9.2%, n = 10 each), and questions about epilepsy-specific driving restrictions (6.4%, n = 7). According to physicians' notes, the following issues were addressed in detail during telemedicine consultations: changes or maintenance of ASD regimens (82.6%, n = 90), general disease-specific questions and aspects (72.5%, n = 79), SARS-CoV-2-associated questions (40.4%, n = 44), seizure frequency (35.8%, n = 39), side effects of ASDs (34.9%, n = 38), ASD prescriptions (33.0%, n = 36), social aspects and supportive services or further diagnostic/therapeutic steps (each 30.3%, n = 33 each), the need for a written change in medication regime (25.7%, n = 28), work or employment issues (11.0%, n = 12), epilepsy-specific driving restrictions (9.2%, n = 10), and finally, the need for medical certificates (4.6%, n = 5). Information on disease-specific and general SARS-CoV-2-related supply problems for patients with epilepsy are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 2.

Reasons, content, and satisfaction with telemedicine appointments (n = 109).

| % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Reasons for the urgent appointment | |

| Disease-specific questions | 57.8 (63) |

| Ongoing or planned change of ASDs | 29.4 (32) |

| Discussion of diagnostic findings and recommendations | 14.7 (16) |

| ASD management during planed, new or known pregnancy | 9.2 (10) |

| Increased seizure frequency | 14.7 (16) |

| ASD side effects | 31.2 (34) |

| Disease-specific driving restrictions | 6.4 (7) |

| Others | 5.5 (6) |

| Content of the telemedicine appointment | |

| Disease-specific questions | 72.5 (79) |

| ASD prescriptions | 33.0 (36) |

| Social aspects and supportive services available | 30.3 (33) |

| SARS-CoV-2-associated questions and aspects | 40.4 (44) |

| Work- or employment-associated aspects | 11.0 (12) |

| Changes or maintenance of ASD regimens | 82.6 (90) |

| Driving restrictions | 9.2 (10) |

| Further diagnostic or therapeutic approaches/steps | 30.3 (33) |

| Medical certificates | 4.6 (5) |

| Seizure frequency-related topics | 35.8 (39) |

| ASD side effects | 34.9 (38) |

| Written medication regime | 25.7 (28) |

| Subjective satisfaction of the telemedical appointment | |

| From the patient's point of view | |

| Completely satisfied | 38.5 (42) |

| Satisfied | 56.9 (62) |

| Less satisfied | 2.8 (3) |

| Unsatisfied | 0.9 (1) |

| Not available | 0.9 (1) |

| From the physician's point of view | |

| Completely satisfied | 46.8 (51) |

| Satisfied | 45.0 (49) |

| Less satisfied | 5.5 (6) |

| Unsatisfied | 0.0 (0) |

| Not available | 2.8 (3) |

| Disadvantage due to switch to telemedical appointment | |

| No | 87.2 (95) |

| Yes | 12.8 (14) |

| Postponing of diagnostic or therapy | 5.5 (6) |

| Limited interpretation of adverse events or symptoms | 5.5 (6) |

| Language barrier (no communication without gestures) | 0.9 (1) |

| Increased uncertainty due to missing face-to-face contact | 0.9 (1) |

ASDs = antiseizure drugs.

3.4. Satisfaction with telemedicine appointments

Most participating patients rated telemedicine appointments as either completely satisfying (38.5%, n = 42) or satisfying (56.9%, n = 62), with three patients less satisfied (2.8%), and one unsatisfied patient (0.9%) (Fig. 3B). The conversion from face-to-face appointments to telemedicine appointments was rated as not being a disadvantage for current treatment in 87.2% (n = 95) of subjects, but in 12.8% (n = 14), it was rated as a disadvantage (Fig. 3C). Other disadvantages were the postponements of diagnostics or therapies (5.5%, n = 5), limited possibilities for interpretation of ASD side effects or other symptoms (5.5%, n = 5), language barrier without gesture-compensated communication (0.9%, n = 1), and increased uncertainty due to lack of face-to-face contact (0.9%, n = 1). From the perspective of counseling physicians, 46.8% (n = 51) of appointments were completely satisfying, 45.0% (n = 49) were satisfying, and 5.5% (n = 6) were less satisfying. No telemedicine appointment was rated as unsatisfying (Fig. 3B). Discrepancies between patients' and physicians' rating of urgency for the appointment were visualized using a Sankey diagram (Fig. 3D). There was no significant difference in urgency ratings between patients' and physicians' view (χ2 = 0.0539, p = 0.8165). In cases of discrepancies, physicians mostly rated the urgency for the appointment lower than the patients themselves.

Univariate analyses of factors associated with the request of telemedicine consultation rather than a postponed face-to-face visit showed significant associations to (Table 3 ): subjectively high-hazard estimations of potential SARS-CoV-2 threats (χ2 = 14.103, p = 0.004); subjectively urgent or very urgent medical needs (χ2 = 96.783, p = 0.004); and female gender (χ2 = 7.067, p = 0.024). There were no significant associations regarding age, drug-refractory course, epilepsy type, seizure semiology, and living environment (urban vs. rural) (all p > 0.05).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 telemedicine care offers (n = 271).

| Aspect | Value | Conversion to telemedicine care accepted |

χ2 | p-Value⁎ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Sum | ||||

| Gender | Female | 71 | 79 | 150 | 7.067 | 0.024 |

| Male | 38 | 83 | 121 | |||

| Epilepsy severity | Active | 83 | 124 | 207 | 0.098 | 0.875 |

| Remission | 20 | 33 | 53 | |||

| Subjective SARS-CoV-2 threat | High | 56 | 51 | 107 | 14.103 | 0.004 |

| Low | 40 | 99 | 139 | |||

| Age | < 45 years | 76 | 104 | 180 | 1.155 | 0.374 |

| ≥ 45 years | 30 | 55 | 85 | |||

| Living environment | Urban | 46 | 73 | 119 | 0.14 | 0.709 |

| Rural | 61 | 88 | 149 | |||

| Subjective appointment urgency | At least urgent | 67 | 12 | 97 | 96.783 | 0.004 |

| Less/nonurgent | 37 | 147 | 184 | |||

| Epilepsy type | Focal | 84 | 90 | 174 | 2.007 | 0.178 |

| Generalized | 16 | 28 | 44 | |||

| Seizure type | Only focal | 25 | 35 | 60 | 0.054 | 0.881 |

| Generalized | 82 | 123 | 205 | |||

p-Values after two-tailed Pearson's chi-squared and post hoc correction on difference between the expected frequencies and the observed frequencies of the mentioned aspect within the cohort, corrected for multiple testing after Benjamini–Hochberg (bold figures represent significant findings).

4. Discussion

The SARS-CoV-2, and its clinical manifestation as COVID-19, currently are in the limelight of scientific and popular media around the world. The SARS-CoV-2 and the consequent restrictions on private and business life have determined everyday life in ways never before imaginable, in addition to controversial discussions of direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on the central nervous system, especially on seizures and epilepsy [[23], [24], [25]]. Physicians are encouraged to share case information, continue investigations, and provide known facts about COVID-19 to patients with epilepsy and their families [26]. The SARS-CoV-2 has led to additional supply problems for patients with chronic diseases, such as epilepsy.

In Germany, a governmental order forced all clinics to immediately suspend elective care on March 16, 2020 to allow hospitals to focus on preparing and expanding their emergency and intensive care capacities [4]. As shown in the SARS outbreak in 2003, pandemic effects on a healthcare system can have devastating effects on patients with epilepsy, mainly due to decreased ambulatory medical supply leading to ASD withdrawals and increased seizure frequencies [27]. In comparison, a recent consensus paper on COVID-19 recommended the reduction of hospital visits for patients with epilepsy to an absolute minimum to decrease the probability of SARS-CoV-2 transmission at possibly “contaminated” medical sites. Physicians were further urged to provide their patients with emergency-care plans, adequate ASD supplies, and detailed individualized information on lifestyle issues and disease-specific information [26,28]. To allow for individualized and ongoing ambulatory care despite the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, telehealth and other telemedical services were seen as having the potential to close these ambulatory supply gaps [28], but their limitations in this context have also been highlighted and discussed [29,30].

To the best of our knowledge, here, we present the first data on the feasibility, acceptance, and satisfaction of a SARS-CoV-2-related conversion from face-to-face ambulatory care visits to telemedicine services for specialized epilepsy care. In this cohort, a large proportion (40.1%) of patients opted for telemedicine consultations rather than a postponed face-to-face visit after their planned onsite appointments had been canceled. The request of a telemedicine visit was significantly associated with medical-need urgency and a high SARS-CoV-2 subjective threat level, in keeping with other reports highlighting personal needs and other intrinsic motivational aspects (such as fear) as important factors for telemedicine acceptance [31,32]. Patients with a nonurgent appointment priority mainly opted for shifting their appointment to a later date. Especially during pandemics, decisions to avoid medical sites are understandable, as reflected by the 3.3% of subjects who reported relief that their initial appointments were canceled. Moreover, the request of telemedicine consultations was significantly associated with being female, matching previous study results on the use of telemedicine and mobile health [[33], [34], [35]]. Exactly why male patients are more hesitant to accept telemedicine and mobile health has not yet been determined, but a general reluctance by male patients to use medical services and medicine [36] could be fundamental, and requires further research to better understand this patient group.

As previously reported, patient satisfaction with telemedicine consultations was high (only 3.8% of subjects being less or unsatisfied) [37]. Most of the reported disadvantages were related to limited interpretations of adverse events or other symptoms, and postponements of diagnostic or therapeutic measures (such as EEG recordings or VNS adjustments) for technical reasons, and increased uncertainty due to missing face-to-face contact. Similar to patient findings, physician satisfaction among the mostly eHealth-naïve physicians in our department was also high, reporting less satisfying results in only 5.5% of cases, and mirroring the high rate of general acceptance of telemedicine in healthcare professionals [38]. A disadvantage remains, however, that the services are not appropriately remunerated and reimbursed by the statutory health insurance [39], so that such a telemedicine service can only be offered for a limited time without endangering the funding of the department.

Another important aspect of this study was to record and analyze SARS-CoV-2 associated supply problems in patients with epilepsy based on experiences with the SARS pandemic in 2003 [27]. Remarkably, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic led to supply problems for 22.9% of the cohort who reported ASD undersupply, and 5.5% of the cohort who reported a shortage of primary outpatient medical care. These results are in line with another study that discussed medical support problems for patients with Parkinson's disease and other movement disorders [40]. For the USA, a similar public healthcare problem has been reported, especially for underserved and homeless people, during the COVID-19 pandemic [41]. Moreover, 9.2% of subjects reported general supply problems with food and sanitary products, which seems high for a industrialized country like Germany that usually has an unrestricted food and consumables supply. A study from China analyzing online research behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic suggested that food supply problems were also present in that country, based on 29.4% of all online queries being in the “food and drinks” category [42]. Patients with epilepsy may be a highly vulnerable group for such supply problems, given the driving restrictions applied to patients with ongoing seizures [43].

Based on its single-center design, this study suffers from several methodical limitations that may influence its generalizability, especially the individual characteristics of clinics within the extremely specialized German ambulatory healthcare system, and the broad availability of unrestricted healthcare services in this country. Moreover, because of the short lead time of the study, no specific outcome measures or comprehensive detection for confounders for the acceptance and feasibility could be implemented [44]. In addition, the lack of alternatives to the offered telemedicine pandemic services during the COVID-19 could have an influence on the reported acceptance and satisfaction. However, the similarity of some of our findings with other studies conducted before or during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic allow for basic international comparisons and extrapolations of the results. To minimize potential biases due to the study design, STROBE and RECORD guidelines were closely followed [16,17].

5. Conclusions

General understanding and acceptance of cancelations of elective face-to-face ambulatory visits and of the option to have telemedicine consultations during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Germany was high, especially in patients with very urgent or urgent appointment priority. Patients with a nonurgent appointment priority mainly opted for shifting their appointment to a later date. Patients who engaged in telemedicine consultations were highly satisfied, supporting the feasibility and potential for telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic, and beyond. Male sex appears to be a risk factor for underutilization of telemedicine services. This barrier should be addressed when future telemedicine services for patients with epilepsy are planned. Moreover, patients with epilepsy seem to suffer from medical and general supply problems, which should be addressed in further studies to improve ambulatory care and medical supply chains for future pandemics or other crises.

Ethical publication statement

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Declaration of competing interest

None of the authors reports conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study analysis was supported by the State of Hessen with a LOEWE-Grant to the CePTER Consortium (https://www.uni-frankfurt.de/67689811).

The establishment of telemedicine services for patients with epilepsy in Hessen was supported under the program “E-Health-Initiative Hessen” by the Hessian Ministry for Social Affairs and Integration (https://soziales.hessen.de/) and Hessian Ministry of Higher Education, Research and the Arts (https://wissenschaft.hessen.de/) with a grant to the Goethe-University and University Hospital Frankfurt (Project title: Establishment and health economic evaluation of telemedical epilepsy care in Hessen; project duration: 2017–2021).

We are grateful to our patients, colleagues, and hospital staff for assistance in conducting this analysis during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107483.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary Table 1: Geographical origins of patients in the study.

Supplementary Table 2: Disease-specific and general SARS-CoV-2-related supply problems for patients with epilepsy (n = 109)

References

- 1.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P., Bretzel G., Froeschl G., Wallrauch C. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeStatis . 2020. Number of daily recorded coronavirus (COVID-19) cases in Germany since January 2020. accessed 27, 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porcheddu R., Serra C., Kelvin D., Kelvin N., Rubino S. Similarity in case fatality rates (CFR) of COVID-19/SARS-COV-2 in Italy and China. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2020;14:125–128. doi: 10.3855/jidc.12600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouffier V., Klose K. In: Fifth regulation on the control of corona virus (Fünfte Verordnung zur Bekämpfung des Corona-Virus) Hessen, editor. 2020. Wiesbaden, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ertl J., Hapfelmeier J., Peckmann T., Forth B., Strzelczyk A. Guideline conform initial monotherapy increases in patients with focal epilepsy: a population-based study on German health insurance data. Seizure. 2016;41:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strzelczyk A., Bergmann A., Biermann V., Braune S., Dieterle L., Forth B. Neurologist adherence to clinical practice guidelines and costs in patients with newly diagnosed and chronic epilepsy in Germany. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;64:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeStatis . Kapitel 4 - Gesundheit: Statistisches Bundesamt (DeStatis) 2020. Statistisches Jahrbuch 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamer H.M., Dodel R., Strzelczyk A., Balzer-Geldsetzer M., Reese J.P., Schoffski O. Prevalence, utilization, and costs of antiepileptic drugs for epilepsy in Germany—a nationwide population-based study in children and adults. J Neurol. 2012;259:2376–2384. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwan P., Arzimanoglou A., Berg A.T., Brodie M.J., Allen Hauser W., Mathern G. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1069–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwan P., Brodie M.J. Definition of refractory epilepsy: defining the indefinable? Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:27–29. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70304-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenow F., Bast T., Czech T., Feucht M., Hans V.H., Helmstaedter C. Revised version of quality guidelines for presurgical epilepsy evaluation and surgical epilepsy therapy issued by the Austrian, German, and Swiss working group on presurgical epilepsy diagnosis and operative epilepsy treatment. Epilepsia. 2016;57:1215–1220. doi: 10.1111/epi.13449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowerison M.W., Josephson C.B., Jette N., Sajobi T.T., Patten S., Williamson T. Association of levels of specialized care with risk of premature mortality in patients with epilepsy. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:1352–1358. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabezudo-Garcia P., Ciano-Petersen N.L., Mena-Vazquez N., Pons-Pons G., Castro-Sanchez M.V., Serrano-Castro P.J. Incidence and case fatality rate of COVID-19 in patients with active epilepsy. Neurology. 2020;95:e1417–e1425. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohannessian R., Duong T.A., Odone A. Global telemedicine implementation and integration within health systems to fight the COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e18810. doi: 10.2196/18810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollander J.E., Carr B.G. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elm v Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies (vol 335, pg 806, 2007) Br Med J. 2008;336:35. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benchimol E.I., Smeeth L., Guttmann A., Harron K., Moher D., Petersen I. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher R.S., Cross J.H., French J.A., Higurashi N., Hirsch E., Jansen F.E. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58:522–530. doi: 10.1111/epi.13670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher R.S., Cross J.H., D'Souza C., French J.A., Haut S.R., Higurashi N. Instruction manual for the ILAE 2017 operational classification of seizure types. Epilepsia. 2017;58:531–542. doi: 10.1111/epi.13671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheffer I.E., Berkovic S., Capovilla G., Connolly M.B., French J., Guilhoto L. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58:512–521. doi: 10.1111/epi.13709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenow F., Akamatsu N., Bast T., Bauer S., Baumgartner C., Benbadis S. Could the 2017 ILAE and the four-dimensional epilepsy classifications be merged to a new “Integrated Epilepsy Classification”? Seizure. 2020;78:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asadi-Pooya A.A., Simani L. Central nervous system manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review. J Neurol Sci. 2020;413 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu L., Xiong W., Liu D., Liu J., Yang D., Li N. New onset acute symptomatic seizure and risk factors in coronavirus disease 2019: a retrospective multicenter study. Epilepsia. 2020;61:e49–e53. doi: 10.1111/epi.16524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vollono C., Rollo E., Romozzi M., Frisullo G., Servidei S., Borghetti A. Focal status epilepticus as unique clinical feature of COVID-19: a case report. Seizure. 2020;78:109–112. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuroda N. Epilepsy and COVID-19: associations and important considerations. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;108 doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai S.L., Hsu M.T., Chen S.S. The impact of SARS on epilepsy: the experience of drug withdrawal in epileptic patients. Seizure. 2005;14:557–561. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.French J.A., Brodie M.J., Caraballo R., Devinsky O., Ding D., Jehi L. Keeping people with epilepsy safe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurology. 2020;94:1032–1037. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brigo F., Bonavita S., Leocani L., Tedeschi G., Lavorgna L., Digital Technologies W. Telemedicine and the challenge of epilepsy management at the time of COVID-19 pandemic. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;110 doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khairat S., Meng C., Xu Y., Edson B., Gianforcaro R. Interpreting COVID-19 and virtual care trends: cohort study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e18811. doi: 10.2196/18811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harst L., Lantzsch H., Scheibe M. Theories predicting end-user acceptance of telemedicine use: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e13117. doi: 10.2196/13117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamal S.A., Shafiq M., Kakria P. Investigating acceptance of telemedicine services through an extended technology acceptance model (TAM) Technology in Science. 2020:60. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khairat S., Liu S., Zaman T., Edson B., Gianforcaro R. Factors determining patients' choice between mobile health and telemedicine: predictive analytics assessment. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7:e13772. doi: 10.2196/13772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rho M.J., Kim H.S., Chung K., In Young Choi. Factors influencing the acceptance of telemedicine for diabetes management. Clust Comput. 2014;18 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Escoffery C. Gender similarities and differences for e-Health behaviors among U.S. adults. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24:335–343. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jimmy B., Jose J. Patient medication adherence: measures in daily practice. Oman Med J. 2011;26:155–159. doi: 10.5001/omj.2011.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waller M., Stotler C. Telemedicine: a primer. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2018;18:54. doi: 10.1007/s11882-018-0808-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanson R.E., Truesdell M., Stebbins G.T., Weathers A.L., Goetz C.G. Telemedicine vs office visits in a movement disorders clinic: comparative satisfaction of physicians and patients. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2019;6:65–69. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.12703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenow F., Audebert H.J., Hamer H.M., Hinrichs H., Kessler-Uberti S., Kluge T. Tele-EEG: current applications, challenges, and technical solutions. Klinische Neurophysiologie. 2018;49:208–215. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papa S.M., Brundin P., Fung V.S.C., Kang U.J., Burn D.J., Colosimo C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Parkinson's disease and movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2020;35:711–715. doi: 10.1002/mds.28067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsai J., Wilson M. COVID-19: a potential public health problem for homeless populations. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e186–e187. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30053-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hua J., Shaw R. Corona virus (COVID-19) “infodemic” and emerging issues through a data lens: the case of China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2309. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willems L.M., Reif P.S., Knake S., Hamer H.M., Willems C., Krämer G. Noncompliance of patients with driving restrictions due to uncontrolled epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;91:86–89. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiner B.J., Lewis C.C., Stanick C., Powell B.J., Dorsey C.N., Clary A.S. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci. 2017;12:108. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: Geographical origins of patients in the study.

Supplementary Table 2: Disease-specific and general SARS-CoV-2-related supply problems for patients with epilepsy (n = 109)