Abstract

Background & Aims:

Outcomes with anticoagulation are understudied in advanced liver disease. We investigated effects of anticoagulation (AC) with warfarin and DOACs on all-cause mortality and hepatic decompensation as well as ischemic stroke, major adverse cardiovascular events, splanchnic thrombosis, and bleeding in a cohort with cirrhosis and atrial fibrillation.

Approach & Results:

This was a retrospective longitudinal study using national data of US Veterans with cirrhosis at 128 medical centers including cirrhosis patients with incident atrial fibrillation from January 1st 2012 to December 31st, 2017 followed through December 31st, 2018. To assess the effects of AC on outcomes, we applied propensity-score (PS) matching and marginal structural models (MSMs) to account for confounding by indication and time-dependent confounding. The final cohort included 2,694 cirrhotic veterans with atrial fibrillation (n=1,694 and n=704 in the warfarin and DOAC cohorts after PS matching, respectively) with a median of 4.6 years of follow-up. All-cause mortality was lower with warfarin vs. no AC: (PS-matched: hazard ratio (HR) 0.65, 95% CI: 0.55-0.76; MSM models: HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.40-0.73) and DOACs vs. no AC (PS-matched: HR 0.68, 95% CI: 0.50-0.93; MSM models: HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.31-0.81). In MSM models, warfarin (HR 0.29, 95% CI 0.09-0.90) and DOACs (HR: 0.23, 95% CI 0.07-0.79) were associated with reduced ischemic stroke. In secondary analyses, bleeding was lower with DOACs compared to warfarin: (HR: 0.49, 95% CI 0.26-0.94).

Conclusions:

Warfarin and DOACs were associated with reduced all-cause mortality. Warfarin was associated with more bleeding compared to no AC. DOACs had a lower incidence of bleeding compared to warfarin in exploratory analyses. Future studies should prospectively investigate these observed associations.

Keywords: oral anticoagulants, liver disease, bleeding, portal hypertension

INTRODUCTION

As we expand our understanding of the complex interplay of pro- and anti-coagulant factors in cirrhosis, the paradigm that cirrhosis generates a state of “auto-anticoagulation” has long been dispelled.(1, 2) The liver synthetic dysfunction associated with cirrhosis is now believed to result in a decreased production of both pro- and anti-coagulant factors resulting in a relative coagulation balance, which can, however, be altered towards thrombosis or bleeding depending on physiologic stressors or specific clinical situations.(2, 3) In fact, venous thromboembolic events have been widely described in cirrhosis and are increasingly being recognized as accelerators of clinical decompensation.(4) Data have also emerged that anticoagulation may prevent liver decompensation and ameliorate portal hypertension (3–6) by reducing microthombosis within small portal radicles and sinusoids and possibly halting the progression of fibrosis.(7)

Despite the increased understanding of the hemostasis in liver disease, practicing clinicians are often reluctant to prescribe anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation and venous thrombosis and the role of anticoagulation in preventing hepatic decompensation remains controversial.(1) Direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs), a newer class of anticoagulants that either directly inhibit the activation of factor Xa (apixaban, betrixaban, endoxaban, and rivaroxaban) or thrombin (dabigatran), have become the most commonly prescribed oral agents to prevent ischemic stroke in atrial fibrillation.(6) However, registration trials for these agents specifically excluded patients with advanced liver disease due to safety concerns as all DOACs undergo hepatic metabolism.(8) Emerging retrospective studies and meta-analyses generally support the efficacy and safety of both warfarin and DOAC utilization in patients with cirrhosis with atrial fibrillation (9–12) and newer data suggest that DOACs are equally as effective as warfarin at preventing ischemic stroke. (11, 12) However, data evaluating hepatic decompensation and mortality with these medications are limited.

Atrial fibrillation is the most common indication for chronic, long-term anticoagulation in the United States (13) and when prescribed for patients with concurrent cirrhosis represents a natural experiment to measure the effect of chronic anticoagulation on macro- and microvascular thrombosis and subsequent liver-related decompensation and death. To investigate the effects of anticoagulation on overall mortality and hepatic decompensation in patients with atrial fibrillation and concurrent cirrhosis, we leveraged the VA Costs and Outcomes in Liver Disease (VOCAL) cohort, which includes detailed clinical longitudinal data on U.S. veterans at 128 medical centers. We additionally explored the effects warfarin and DOACs on the secondary outcomes of ischemic stroke, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), splanchnic thrombosis, and bleeding.

METHODS:

Cohort Identification

The VA is the single largest integrated health-care system in the U.S. The VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) is a national database that contains longitudinal demographic as well as outpatient and inpatient pharmacy, claims, and clinical data on approximately 9 million Veterans across all 50 states.(14) The VOCAL cohort was derived from the CDW using validated methodology, which has been previously published in detail and includes greater than 120,000 veterans diagnosed with cirrhosis based on having at least one inpatient or two outpatient International Classification of Diseases version 9 (ICD9-CM) or ICD10-CM diagnostic codes (ICD9-CM: 571.2, 571.5, 571.6; ICD10-CM: K74.*, K70.3*). (15, 16) The Institutional Review Board at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center in Philadelphia approved the study.

Eligibility criteria

We included patients with prevalent cirrhosis and one inpatient or two outpatient ICD-9-CM (427.31) ICD-10 CM (I48.0, I48.1, I48.2, I48.3, I48.4, I48.91, I48.92) codes for atrial fibrillation (Table S1). We limited our cohort to patients with a new diagnosis code of atrial fibrillation to the more contemporary era from January 1st, 2012 to December 31st, 2017 during which DOACs became available in the VA. All patients were followed through December 31st, 2018. We excluded patients with any pre-cirrhosis atrial fibrillation by diagnosis codes, any previous prescriptions for DOACs or warfarin in the VA system, valvular heart disease, splanchnic t (portal vein, mesenteric) thrombosis, and prior venous thromboembolic events such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) (Table S1).(17, 18)

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality and hepatic decompensation Secondary outcomes were ischemic stroke, MACE, and bleeding events. Death was ascertained using the VA Vital Status Master file, which contains dates of death cross-referenced with all main federal mortality databases and has a sensitivity of greater than 90% compared with state death certificate registries.(19) Hepatic decompensation was defined with a previously validated VA algorithm as the presence of at least one inpatient or two outpatient ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM codes for ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), variceal hemorrhage, or HCC that appeared after the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. This algorithm was previously shown to have positive predictive value of greater than 90% for decompensation.(20) Death after hepatic decompensation was defined as death after having a diagnosis code of any of the decompensating events. Ischemic stroke was defined by diagnosis codes (Table S1). MACE was defined as the first onset of cerebrovascular accident, acute myocardial infarction or revascularization with a previously validated algorithm and previously described in detail.(21, 22) The definition of bleeding was adapted to the VA setting from validated criteria and consensus guidelines and defined as having any of the following after the diagnosis of cirrhosis i) ≥ 2 gram per deciliter hemoglobin drop on 2 two consecutive laboratory tests within a 90-day period, ii) any ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM codes for intracranial bleeding including hemorrhagic stroke (Table S2), iii) admission requiring any packed red blood cell transfusion, iv) primary discharge diagnosis codes of gastrointestinal bleeding, hemarthrosis, or other bleeding (Table S2).(23, 24)

Covariates

Baseline variables

All patient-level covariates were measured within 180 days prior to or for 30 days after the date of the first atrial fibrillation diagnosis or warfarin/DOAC prescription. These included demographics (age, sex, race), medical comorbidities and psychosocial factors, liver disease etiology and severity, and hospital characteristics. Medical comorbidities were identified by diagnosis codes and/or by clinical data from the EHR.(22) Diabetes defined using a previously validated VA algorithm (25), hypertension, and history of stroke were ascertained with diagnosis codes (Table S1).(22) The CHADS2 score was calculated from its component variables.(26) Current aspirin use was obtained using pharmacy data. Obesity was defined as having body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 at least once during the baseline period. The cirrhosis comorbidity index used for comorbidity adjustment includes ICD9-CM/ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes for acute myocardial infarction, peripheral arterial disease, epilepsy, substance abuse other than alcoholism, heart failure, cancer, and chronic kidney disease.(27) Alcohol use was ascertained using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C), which is annually administered in VA primary care clinics; a score of ≥4 for men and ≤3 for women was classified as alcohol misuse.(28) Tobacco use was obtained from the VA “Health Factors” file, which is updated annually by primary care providers. Liver disease etiology and the Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score was defined using previously validated methodology.(29, 30) Total serum bilirubin, serum albumin, international normalized ratio (INR) and platelet count were obtained from the laboratory database. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was determined using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation widely used in liver disease.(31) VA facility characteristics included geographic region and a VA measure of hospital complexity, which is based on the availability of invasive procedures (e.g. open heart surgery, cardiac catheterization, etc).(32)

Time-updated variables

In addition to baseline variables, time-updated laboratory values, measures of liver disease severity, and outcomes that could affect treatment assignment and clinical outcomes longitudinally were obtained and updated over each quarter of follow-up as per previous methodology.(22) Specifically, CTP score, total serum bilirubin, serum albumin, platelet count, eGFR, bleeding and thrombotic events (see Outcomes section) were included. Missing laboratory data were imputed in R programming environment using the MICE package with a random forest algorithm.(33)

Exposures

Prescription data was obtained from the VA pharmacy database in 30-day intervals. Patients were considered exposed to AC if receiving a prescription for any dose of warfarin or DOAC for at least 7 days in any 30-day window. Given the retrospective, observational nature of the data, we employed causal inference methods to address confounding by indication and minimize bias across groups. The primary analysis was a propensity-score (PS) matched intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis whereby treatment was assigned 90 days from the date that the atrial fibrillation diagnosis code was first entered into the electronic health record (EHR) or the date of the first AC prescription whichever came first. The rationale for the 90-day window was to allow enough time for patients to be referred and assigned treatment by clinicians. Following the ITT assumption, patients were considered exposed to their initial treatment assignment with warfarin, DOACs, or no AC for the remainder of follow-up. A secondary analysis employing marginal structural models (see Analysis Plan) was conducted “as-treated” whereby drug exposure was assessed cumulatively over the duration of follow-up in 30-day intervals with clinical variables, which were time-updated quarterly.

Analysis Plan

Analyses were conducted with Stata 15.1 (Statacorp LP, College Station, TX) and R programming environment using 2-sided hypothesis testing with p value <.05 considered statistically significant. Descriptive statistics using means, medians, standard deviations, and interquartile ranges where appropriate were used to describe demographic and clinical variables. Incidence rates of clinical outcomes were calculated by dividing the number of events by the person-time at risk. The primary analyses were PS-matched ITT analyses of drug exposure (see Exposures). PS matching (Stata psmatch2) balanced covariates across patients treated with warfarin compared to no AC and DOACs versus no AC. PS matching estimates the effect of the outcome across different exposure groups by collectively balancing risk factors across each exposure group.(34) Covariates were chosen a priori and were based on clinical relevance and previously demonstrated associations with the drug exposure assignment and clinical outcomes. We used 3:1 matching with caliper of 0.1 and verified sufficient balance by examining balance plots, kernel-density plots, standardized differences (<10%), Rubin’s B (<25%), and Rubin R (0.5-2).(35) The list of covariates and absolute standardized differences prior to and after PS-matching are shown in Table S3. We specifically matched on aspirin use as this can affect the efficacy of anticoagulation and increase the risk of bleeding. Subsequently, Cox models were fit in the PS-matched cohorts with drug exposure as the independent variable with robust standard errors to account for clustering across matches. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated in the matched samples to visually assess the impact of drug exposure on clinical outcomes.

“As-treated” analyses accounting for time-updated drug exposure were conducted using marginal structural models (MSMs), which apply inverse probability weighting in discrete time failure models.(36, 37) MSMs incorporate time-updated confounders into a model to facilitate causal estimation of the association between a time-updated exposure and the outcome. Applying the inverse probability weights creates a pseudo-population in which covariates are balanced across the population to attempt to mimic randomization at the time of the anticoagulant exposure period. We used these models to assess relationships between time-updated drug exposures and time-dependent confounders (CTP scores, total serum bilirubin, serum albumin, platelet count, eGFR, stroke, clotting events [PVT, SMV thrombus, DVT, PE], ischemic stroke, and major bleeding events) that could affect both time-dependent treatment decisions and the outcomes. Drug exposure was evaluated in 30-day windows based on prescription data. Time-updated confounders were updated quarterly. MSM models were fit with a 2-step approach to first predict the treatment exposure (warfarin versus no AC or DOAC versus no AC) followed by inverse-probability treatment weighted models for the outcomes of all-cause mortality and hepatic decompensation. Stabilized weights were obtained using baseline variables and were truncated at the 99th percentile.(37) A sensitivity analysis was conducted removing 114 patients who received concurrent or alternating warfarin and DOAC prescriptions during the follow-up period. A secondary sensitivity analysis fit MSM models adjusting for time-updating HCV viremia.

Secondary outcomes of ischemic stroke, MACE, and bleeding were analyzed with similar approaches with PS-matched Cox and MSM models as described above. Splanchnic thrombotic events were insufficiently frequent to be modeled. An exploratory PS-matched Cox analysis was conducted comparing rates of bleeding between warfarin-exposed and DOAC-exposed patients (covariate balance shown in Table S4).

RESULTS:

Cohort Identification

A total of 118,146 patients with new diagnosis codes of cirrhosis were initially identified from the VOCAL cohort. Of those, 15,767 (13.3%) carried a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. A total of 10,227 were excluded due to pre-existing atrial fibrillation or a history of valvular heart disease prior to the diagnosis of cirrhosis, 259 were excluded for previous DVT, PE, or splanchnic thrombosis, and 2,587 were excluded due to atrial fibrillation diagnosis prior to the DOAC era (January 1st, 2012) leaving 2,694 veterans in unmatched sample (Figure S1). Prior to PS matching, 638 (23.6%) veterans were prescribed warfarin, 214 (7.9%) DOACs, and 1842 (68.4%) did not receive anticoagulation (AC) within 90 days of the atrial fibrillation diagnosis. PS matching yielded 1,694 veterans for the warfarin cohort (614 on warfarin and 1,080 matched controls) and 704 for the DOAC cohort (201 on DOACs and 503 matched controls); outcomes assessed with marginal structural models used the entire eligible sample of 2,694 patients.

After propensity matching with untreated patients (Table S3), baseline characteristics of Veterans with cirrhosis and newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation treated either with warfarin or DOACs were well-matched with respect to demographic characteristics, baseline medical comorbidities, liver disease etiology and severity, and hospital-level variables (Table 1). The median age ranged from 63-64 years. As expected, greater than 98% were male, two-thirds were white. Up to 10% of patients had a previous history of stroke, 53-55% had baseline diabetes, nearly all veterans had documented hypertension as previously shown in the VA and the median CHADS2 score was 2 (interquartile range: 1-2).(22) Slightly more than half of the patients were taking aspirin in the warfarin, DOAC, and no AC groups. A total of 15-17% of patients had ongoing alcohol misuse and about half were current smokers. The most common etiologies of liver disease were hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcohol. The median MELD score was 10-11 [IQR 8-14]. In the warfarin-matched cohort, 73% of veterans not on anticoagulation (AC) were CTP-A and 26% were CTP-B compared to 70% CTP-A and 29.5% CTP-B of those treated with warfarin; only 1% of patients were CTP-C. Notably, in the DOAC-matched cohort, about 90% of patients were CTP-A, 10% were CTP-B with no CTP-C patients.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Veterans with Cirrhosis and Newly Diagnosed Atrial Fibrillation in Propensity Matched Intention-to-Treat Cohorts

| Warfarin-matched cohort |

DOAC-matched cohort |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Anticoagulation n=1080 |

Warfarin n=614 |

P value | No Anticoagulation n=503 |

DOACs n=201 |

P value | |

| Variabler | ||||||

| Age, M (SD), median [IQR] | 64.2 (8.4), 63 [59-69] | 64.6 (7.5) 64 [60-68] |

0.36 | 64.3 (8.4), 63 [59-69] | 64.0 (7.7), 64 [60-68] | 0.67 |

| Male, n (%) | 1,064 (98.5) | 603 (98.2) | 0.62 | 497 (98.8) | 200 (99.5) | 0.40 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.69 | 0.99 | ||||

| White | 762 (70.6) | 429 (70.0) | 336 (66.8) | 133 (66.2) | ||

| Black | 139 (12.9) | 93 (15.2) | 73 (14.5) | 32 (15.9) | ||

| Hispanic | 72 (6.7) | 37 (6.0) | 40 (8.0) | 16 (8.0) | ||

| Other/unknown | 107 (10.0) | 55 (9.0) | 54 (10.7) | 20 (10.0) | ||

| Comorbidities and habits | ||||||

| CHF, n (%) | 111 (10.3) | 78 (12.7) | 0.13 | 44 (8.8) | 20 (10.0) | 0.62 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 577 (53.4) | 339 (55.2) | 0.48 | 271 (53.9) | 111 (55.2) | 0.75 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1,052 (97.4) | 603 (98.2) | 0.29 | 480 (95.4) | 193 (96.0) | 0.73 |

| History of stroke, n (%) | 108 (10.0) | 57 (9.3) | 0.63 | 41 (8.2) | 14 (7.0) | 0.60 |

| CHADS2 score, mean (SD), median [IQR] | 2.1 (1.2) 2 [1-2] |

2.1 (1.1) 2 [1-2] |

0.36 | 2.0 (1.2), 2 [1-2] | 1.9 (0.9), 2 [1-2] | 0.80 |

| On aspirin, n (%) | 588 (54.5) | 365 (59.5) | 0.05 | 278 (55.3) | 117 (58.2) | 0.48 |

| Obesity (body mass index >30), n (%) | 867 (80.3) | 56 (82.4) | 0.28 | 406 (80.7) | 161 (80.1) | 0.85 |

| Cirrhosis comorbidity index*, n (%) | 0.47 | 0.45 | ||||

| 0 | 558 (51.7) | 309 (50.3) | 262 (52.1) | 99 (49.3) | ||

| 1+0, 1+1 | 360 (33.3) | 199 (32.4) | 166 (33.0) | 76 (37.8) | ||

| 3+0, 3+1, 5+0/5+1 | 162 (15.0) | 106 (17.3) | 75 (14.91) | 26 (12.9) | ||

| Prior history of substance abuse, n (%) | 677 (62.7) | 364 (59.3) | 0.17 | 328 (65.2) | 125 (67.2) | 0.62 |

| Alcohol misuse, n (%) | 183 (16.9) | 98 (16.0) | 0.60 | 81 (16.1) | 30 (14.9) | 0.70 |

| Tobacco use, n (%) | 0.33 | 0.56 | ||||

| Current smoker | 529 (49.0) | 276 (45.0) | 252 (50.1) | 111 (55.2) | ||

| Former smoker | 290 (26.9) | 187 (30.5) | 143 (28.4) | 51 (25.4) | ||

| Never smoker | 246 (22.8) | 144 (23.5) | 102 (20.3) | 38 (18.9) | ||

| Unknown | 15 (1.4) | 7 (1.1) | 6 (1.2) | 1 (0.50) | ||

| Liver disease etiology/severity | ||||||

| HCV/alcohol, n (%) | 778 (72.0) | 444 (72.3) | 0.90 | 363 (72.2) | 146 (72.6) | 0.90 |

| NAFLD/NASH, n (%) | 205 (19.0) | 115 (18.7) | 0.90 | 86 (17.1) | 32 (15.9) | 0.71 |

| Other, n (%) | 97 (9.0) | 55 (9.0) | 0.99 | 54 (10.7) | 23 (11.4) | 0.78 |

| MELD score, mean (SD), median [IQR] | 11.5 (4.7), 11 [8-15] | 10.7 (4.1), 11 [8-14] | 0.59 | 11.0 (4.3) 10 [8-13] |

10.6 (3.6), 10 [8-13] | 0.77 |

| Total serum bilirubin (mg/dL), mean (SD), median [IQR] | 1.2 (1.2), 0.9 [0.6-1.4] | 1.1 (1.6), 0.8 [0.6-1.2] | 0.30 | 1.3 (2.0) 0.9 [0.6-1.3] |

1.2 (1.6), 0.8 [0.6-1.2] | 0.56 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL), mean (SD), median [IQR] | 3.6 (0.6), 3.7 [3.2-4.0] | 3.6 (0.6), 3.7 [3.3-4.0] | 0.06 | 3.7 (0.6) 3.7 [3.3-4.1] |

3.7 (0.6), 3.8 [3.4-4.0] | 0.70 |

| eGFR (mL/min), mean (SD), median [IQR] | 77.9 (38.5), 76.3 [54-97] | 73.2 [31.8] 73 [53.3-93.5] |

0.04 | 79.2 (38.2), 76 [56.3-98] | 79.3 (25.2), 79 [62-95] | 0.51 |

| INR mean (SD), median [IQR] | 1.1 (0.3), 1.1 [1.0-1.2] | 1.2 (0.4) 1.1 [1.0-1.2 |

0.47 | 1.2 (0.3), 1.1 [1-1.2] | 1.2 (0.1), 1.1 [1-1.2] | 0.29 |

| Platelet count x 109/L | 155.7 (78.6), 140.3 [100-196] | 161.7 (65.7), 152 [117-202] | 0.002 | 164.9 (73.9), 159 [114-205] | 170.5 (61.1), 164 [124-209] | 0.10 |

| CTP score, n (%) | 0.21 | 0.65 | ||||

| A (5-6) | 788 (73.0) | 429 (69.9) | 455 (90.5) | 184 (91.5) | ||

| B (7-9) | 280 (25.9) | 181 (29.5) | 48 (9.5) | 17 (8.5) | ||

| C (10-15) | 12 (1.1) | 4 (0.65) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Hospital Characteristics | ||||||

| Geographic Region, n (%) | 0.09 | 0.26 | ||||

| Northeast | 173 (16.1) | 110 (17.9) | 79 (15.8) | 26 (12.9) | ||

| Southeast | 257 (23.9) | 146 (23.8) | 119 (23.8) | 63 (31.3) | ||

| Midsouth | 212 (19.7) | 108 (17.6) | 99 (19.8) | 42 (29.8) | ||

| Central | 169 (15.7) | 122 (19.9) | 72 (14.4) | 25 (12.4) | ||

| West | 264 (24.6) | 127 (20.7) | 132 (26.4) | 45 (22.4) | ||

| Hospital complexity, n (%) | 0.50 | 0.68 | ||||

| High | 946 (91.1) | 550 (92.6) | 431 (90.6) | 174 (91.6) | ||

| Medium | 60 (5.8) | 31 (5.2) | 23 (4.8) | 10 (5.3) | ||

| Low | 32 (3.1) | 13 (2.2) | 22 (4.6) | 6 (3.2) | ||

| Hepatic decompensation, n (%) | 145 (13.4) | 76 (12.4) | 0.54 | 67 (13.3) | 16 (8.0) | .05 |

| Death, n (%) | 576 (53.3) | 243 (39.6) | <.001 | 248 (49.3) | 51 (25.4) | <.001 |

| Death after hepatic decompensation*, n (%) | 261 (45.3) | 109 (44.9) | 0.91 | 70 (28.2) | 15 (29.4) | 0.86 |

| Follow-up time (days), median [IQR] | 1730.5 [959.5-2583.5] |

1881 [1146-2569] |

0.034 | 1903 [1238-2566] |

1731 [971-2536] |

0.24 |

Abbreviations: CHF-congestive heart failure, CTP-Child Turcotte Pugh Score, eGFR-estimated glomerular filtration rate, IQR-interquartile range, INR-international normalized ratio, M-mean, SD-standard deviation, VA-veterans affairs CHADS2 score predicts risk of stroke in atrial fibrillation and consists of the following variables (CHF, hypertension, age ≥75, diabetes, prior history of stroke/transient ischemic attack)

Denominator=total number of deaths

Both warfarin and DOAC therapy were associated with reduced incidence of all-cause mortality (Table 2) compared with no AC. In the warfarin-matched cohort, the incidence rate of all-cause mortality was 27.2 per 100 person-years among patients with no AC compared to 17.0 with warfarin (P<.001). Mortality incidence rates were similar in the DOAC-matched cohort (16.1 with DOACs, 23.1 with no AC; P<.01). The incidence rate of hepatic decompensation was significantly lower in the warfarin versus no AC cohort (5.3 per 100 person-years with warfarin versus 7.1 with no AC; P=.02), however, this was not significant in the DOAC versus no AC cohort (6.3 per 100 person-years with no AC versus 4.6 with DOACs; P=.14). (. The incidence rate of death after hepatic decompensation was lower with warfarin compared to no AC (7.6 per 100 person-years with warfarin versus 12.4 with no AC; P<.001); this difference was numerically lower but not statistically significant with DOACs. The incidence of splanchnic thrombosis was 0.5 per 100-person years in the no AC group compared to 0.3 with warfarin (P=.05). In the DOAC-matched cohort, the incidence rates of death, hepatic decompensation, and death/decompensation were similarly lower with DOACs versus no AC (P<.05 for all comparisons) and event rates were similar. There was no difference in the incidence of splanchnic thrombosis by anticoagulation status in the DOAC cohort. No significant differences were observed in the incidence of ischemic stroke, MACE, or bleeding in the warfarin or DOAC cohort.

Table 2.

Incidence Rates of All-Cause Mortality, Hepatic Decompensation, Ischemic Stroke, Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACEs), Splanchnic Thrombosis and Bleeding in Intention-to-Treat Propensity-Matched Cohorts

| Warfarin-matched cohort | DOAC-matched cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Anticoagulation n=1080 |

Warfarin n=614 |

P value | No Anticoagulation n=503 |

DOACs n=201 |

Pvalue | |

| All-cause mortality | 27.2 | 17.0 | <0.001 | 23.1 | 16.1 | <0.01 |

| Hepatic decompensation | 7.1 | 5.3 | 0.02 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 0.14 |

| Death after hepatic decompensation | 12.4 | 7.6 | <0.001 | 6.7 | 4 | 0.12 |

| Ischemic Stroke | 1.7 | 2.3 | 0.11 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 0.18 |

| MACE | 3.8 | 3.4 | 0.21 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 0.36 |

| Splanchnic thrombosis | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.27 |

| Bleeding | 5.4 | 5.9 | 0.29 | 4.8 | 3.6 | 0.21 |

Abbreviations: CTP-Child-Turcotte-Pugh, DOAC-direct oral anticoagulant, DVT-deep vein thrombosis, PE-pulmonary embolism, MACE-major adverse cardiovascular event

Incidence rates per 100 person-years of follow-up

Bleeding defined as: ≥ 2 gram per deciliter hemoglobin drop on 2 two consecutive laboratory tests, any ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM code for intracranial bleeding including hemorrhagic stroke, admission requiring any packed red blood cell transfusion, or a discharge diagnosis code of gastrointestinal bleeding, hemarthrosis, other bleeding in the first position

MACE (major adverse cardiovascular event) defined as: ischemic stroke, acute myocardial infarction or revascularization

Models evaluating the primary outcomes of all-cause mortality and hepatic decompensation are displayed in Table 3. Warfarin compared to no AC was associated with lower mortality in a PS-matched cohort (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.55-76) and marginal structural model (MSM) (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.40-0.73). Results were similar for DOACs versus no AC (PS-matched: HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.50-0.93; MSM: HR 0.50, 95% CI: 0.31-0.81). Both warfarin (MSM: 0.53, 95% CI 0.37-0.98) and DOACs (MSM: HR 0.44, 95% CI 0.26-0.72) were associated with lower rates of hepatic decompensation in MSM models; there were no significant differences in rates of hepatic decompensation in PS-matched models. Results were similar in secondary analyses when adjusting for time-updating HCV viremia. Kaplan-Meier curves are shown in Figure 1 (Panel A: Warfarin, Panel B: DOACs) for all-cause mortality and in Figure 2 (Panel A: Warfarin, Panel B: DOACs) for hepatic decompensation. Table S5 shows the percentage of the type of new hepatic decompensation within each cohort and stratified by CTP class. Ascites was the most commonly coded new decompensation event followed by varices.

Table 3.

Effect of Warfarin and Direct-Acting Oral Anticoagulants on the All-Cause Mortality and Hepatic Decompensation Compared to No Anticoagulation

| Model Specification | All-cause mortality | Hepatic Decompensation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warfarin versus no AC | DOAC versus no AC | Warfarin versus no AC | DOAC versus no AC | |||||

| n | HR (95% CI) | n | HR (95% CI) | n | HR (95% CI) | n | HR (95% CI) | |

| ITT PS-matched cohorts: | 1,694 | 0.65╪ (0.55-0.76) | 704 | 0.68┼ (0.50-0.93) | 1,664 | 0.73 (0.54-1.02) | 695 | 0.71 (0.40-1.28) |

| Marginal structural model:* | 2,694 | 0.54╪ (0.40-0.73) | 2,694 | 0.50┼ (0.31-0.81) | 2,694 | 0.53┼ (0.37-0.98) | 2,694 | 0.44╪ (0.26-0.72) |

Abbreviations: AC-anticoagulation, CI-confidence interval, DOAC-direct-acting anticoagulant, HR-hazard ratio, ITT-intention to treat, PS-propensity score

Baseline covariates used for adjustment, weighting and/or matching: age, race, etiology of liver disease, diabetes, hypertension, congestive heart failure, obesity, serum total bilirubin, serum albumin, platelet count, eGFR, Child Turcotte Pugh score, alcohol misuse, history of substance abuse, tobacco use, cirrhosis comorbidity index, geographic region, hospital complexity Adjusted for/weighted with time-dependent total serum bilirubin, serum albumin, platelet count, Child-Turcotte Pugh (CTP) scores, eGFR, platelet count, ischemic stroke and bleeding complications in addition to baseline covariates

p<.05

p<.001

Figure 1.

Panel A. Kaplan-Meier Curve of All-Cause Mortality: Warfarin versus no AC in a Propensity-Matched Cohort (n=1694)

Panel B. Kaplan-Meier Curve of All-Cause Mortality: DOAC versus no AC in a Propensity-Matched Cohort (n=704)

Figure 2.

Panel A. Kaplan-Meier Curve of Hepatic Decompensation: Warfarin versus no AC in a Propensity-Matched Cohort (n=1164)

Panel B. Kaplan-Meier Curve of Hepatic Decompensation: DOAC versus no AC in a Propensity-Matched Sample (n=704)

No significant differences in the incidence of stroke were found in the PS-matched ITT analyses comparing warfarin and DOACs to no AC (Table 4). However, MSM models that evaluated drug exposure in 30-day intervals showed lower incidence of stroke for warfarin compared to no AC (HR 0.29, 95% CI 0.09-0.90) and DOACs compared to no AC (HR 0.23, 95% CI 0.07-0.79). Warfarin was associated with lower MACE in the MSM model only (HR 0.25, 95% CI 0.07-0.87) whereas DOACs were not.

Table 4.

Effect of Warfarin and Direct-Acting Oral Anticoagulants on the Secondary Outcomes of Ischemic Stroke, Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events, and Bleeding Compared to No Anticoagulation

| Model Specification | Ischemic Stroke | MACE | Bleeding | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warfarin versus no AC | DOAC versus no AC | Warfarin versus no AC | DOAC versus no AC | Warfarin versus no AC | DOAC versus no AC | |||||||

| n | HR (95% CI) | n | HR (95% CI) | n | HR (95% CI) | n | HR (95% CI) | n | HR (95% CI) | n | HR (95% CI) | |

| ITT PS-matched cohorts: | 1,694 | 1.40 (0.82-2.39) | 704 | 0.47 (0.16-1.36) | 1,694 | 0.86 (0.71-1.04) | 704 | 0.45 (0.18-1.09) | 1,694 | 1.50┼ (1.10-2.06) | 0.77 (0.40-1.48) | |

| Marginal structural models:* | 2,694 | 0.29┼ (0.09-0.90) | 2,694 | 0.23┼ (0.07-0.79) | 2,694 | 0.25┼ (0.07-0.87) | 2,694 | 0.38 (0.09-1.65) | 2,694 | 1.29 (0.74-2.26) | 0.37 (0.13-1.07) | |

Abbreviations: AC-anticoagulation, CI-confidence interval, DOAC-direct-acting anticoagulant, HR-hazard ratio, ITT-intention to treat, MACE-major adverse cardiovascular event, PS-propensity matched

Baseline covariates used for adjustment, weighting and/or matching: age, race, etiology of liver disease, diabetes, hypertension, congestive heart failure, obesity, serum total bilirubin, serum albumin, platelet count, eGFR, Child Turcotte Pugh score, alcohol misuse, history of substance abuse, tobacco use, cirrhosis comorbidity index, geographic region, hospital complexity Bleeding defined as: ≥ 2 gram per deciliter hemoglobin drop on 2 two consecutive laboratory tests, any ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM code for intracranial bleeding including hemorrhagic stroke, admission requiring any packed red blood cell transfusion, or a discharge diagnosis codes of gastrointestinal bleeding, hemarthrosis, other bleeding in the first position MACE defined as: ischemic stroke, acute myocardial infarction or revascularization

Adjusted for/weighted with time-dependent total serum bilirubin, serum albumin, platelet count, Child-Turcotte Pugh (CTP) scores, eGFR, platelet count, and bleeding complications in addition to baseline covariates

p<.05,

p<.001

Detailed information regarding the overall proportion of bleeding and bleeding event types stratified by CTP class is shown Table S5. In the warfarin cohort there were 198 index bleeding events; 169 (85%) were gastrointestinal, 13 (6.6%) were intracranial, 3 (1.5%) hemarthroses, and 13 (6.6%) other. There were 62 index bleeding events reported in the DOAC cohort; 55 (89%) were gastrointestinal, 2 (3.2%) were intracranial, and 5 (8.1%) were reported as other bleeding. Warfarin was associated with increased bleeding compared to no AC (HR 1.50, 95% CI 1.10-2.06) in PS-matched analysis only. DOACs were not associated with bleeding in either the PS-matched or MSM models. Analyses with MSM models after removing 114 patients treated with concurrent warfarin and DOACs or alternating warfarin and DOACs showed similar effect estimates.

Table S6 shows the incidence rate of primary and secondary outcomes stratified by CTP class for the warfarin and DOAC-matched cohorts. Warfarin was associated with lower all-cause mortality among both CTP-A and CTP-B veterans although the magnitude of effect was higher in CTP-B. For the DOAC-matched cohort, the incidence rate of mortality was observed to be lower among CTP-A patients only, however, the sample of CTP-B patients treated with DOACs was small (n=17). With regards to hepatic decompensation, the incidence rate was observed to be lower with warfarin compared to no AC among CTP-B patients only and no differences were observed in the DOAC cohort. Cardiovascular event incidence rates were generally low and similar by CTP-class and anticoagulation status. A lower incidence rate of bleeding was observed with warfarin versus no AC (4.2 per 100-person years with warfarin, 9.1 with no AC, P=.002).

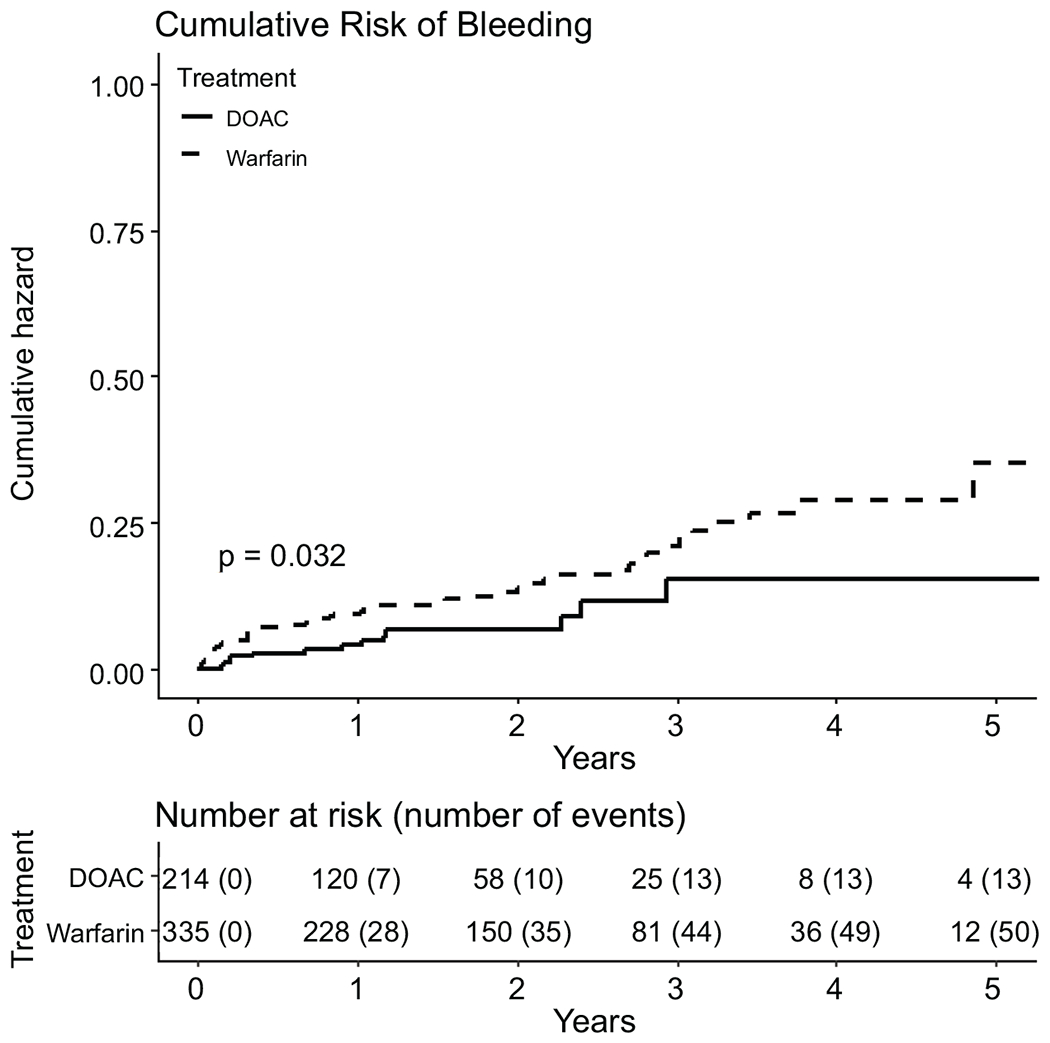

In a further exploratory analysis, we compared bleeding events rates with warfarin to DOACs in a separate PS-matched cohort of 549 veterans (335 (61%) treated with warfarin and 214 (39%)) with DOACs with (CONSORT diagram shown in Figure S1). The incidence rate of bleeding was higher with warfarin compared to DOACs at 6.8 versus 4.1 per 100-person years, respectively (P=.03). The rate of bleeding was lower among patients treated with DOACs compared to warfarin in a PS-matched model (HR: 0.49, 95% CI 0.26-0.94, P=.03). The cumulative incidence of bleeding comparing warfarin to DOACs is shown in Figure 3. Table S7 shows the incidence rates of clinical events stratified by aspirin (ASA) use. Concurrent ASA use in addition to anticoagulation was not associated with higher incidence rates of bleeding events.

Figure 3.

Cumulative Hazard of Bleeding in Propensity-Matched Cohort of Patients on Warfarin versus DOACs (n=549)

DISCUSSION

In a large national cohort of veterans with existing cirrhosis and new onset atrial fibrillation, treatment with either warfarin or DOACs was associated with lower all-cause mortality compared to no anticoagulation. Hepatic decompensation was lower with both warfarin and DOACs in analyses limited to marginal structural models. The rationale for choosing patients with atrial fibrillation and specifically excluding patients with previous splanchnic thrombosis and venous thromboembolic disease was to simulate a primary prevention study of the effect of chronic anticoagulation on mortality and decompensation in patients with cirrhosis. We noted that 33% of patients were treated with anticoagulation. This is comparable to other recent studies showing anticoagulation use of 8 to 22% among patients with atrial fibrillation with cirrhosis, (9) (38) in contrast to about 50%-60% in non-cirrhotic patients.(39, 40) Our study used high-dimensional, longitudinal data and advanced causal-inference methods to account for time-updated factors that are likely to influence decisions around anticoagulation use as well as patient outcomes and address, to the extent possible, confounding by indication in a retrospective cohort.

There is moderately strong evidence that prophylactic anticoagulation among patients with cirrhosis might not only reduce portal vein thrombosis but also improve overall survival. The strongest evidence derives from a prospective, randomized controlled trial in Child-Turcotte-Pugh B7-C10 patients designed to evaluate the efficacy of low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH) in preventing initial portal vein thrombosis.(5) Not only did LMWH markedly reduce incident PVT by 90%, but it also reduced death and hepatic decompensation by nearly 70%. A recent abstract similarly showed decompensation rates of 18% among patients with CTP-A cirrhosis treated with oral vitamin K antagonists compared to 39% on no anticoagulation.(41)

Extrapolating data from animal models of cirrhosis, which suggest that local reduction of protein S expression within hepatocytes and dysfunctional sinusoidal endothelium can result in microthrombosis within the acinar microcirculation,(42) the survival benefit observed could have resulted not only from reduced macrovascular thrombosis but also reduction of microthrombosis. Intrahepatic microthrombosis has been implicated in the acceleration of hepatic stellate cell activation and fibrogenesis via direct activation of HSCs by thrombin and Protein Xa.(7) In chemically-induced liver cirrhosis in animal models, both enoxaparin and rivaroxaban have been shown to lower portal pressure and reduce sinusoidal collagen deposition putatively by preventing microthromboses.(43, 44) Warfarin, though theoretically less suitable for patients with cirrhosis given its potential to further decrease vitamin-K-dependent anticoagulant factors such as Protein C(45), was found to have a similar effect compared to no anticoagulation as DOACs in this study. Only prospective studies can determine whether DOACs have more beneficial effects on liver-related outcomes compared to warfarin. Mechanistic studies are similarly needed to confirm whether the benefits anticoagulation occur through the prevention of macro- or microvascular thrombosis, both, or more direct effects on the liver sinusoidal endothelium.

We observed a decreased risk of stroke with both DOACs and warfarin and a decreased risk of MACE with warfarin only compared to no anticoagulation in MSM models, but not in PS-matched ITT cohorts. Our findings are supported by a recent study from Taiwan that also found that anticoagulation with warfarin or DOACs decreased the risk of ischemic stroke in patients with cirrhosis and atrial fibrillation without increasing the risk of intracranial hemorrhage.(9) The observed differences in our findings between the PS-matched and MSM models may have been twofold. First, PS-matched models had lower sample sizes. Second, PS-matching simulated “intention-to-treat” scenarios whereby treatment assignment in the first 90 days was assumed to be the treatment for the entire duration of follow-up. By contrast, MSM models evaluated actual drug exposures (“as-treated”) in 30-day intervals, accounted for time-updated confounders that may have influenced decisions around treatment, and had greater power to detect differences in outcomes.

We found that bleeding events were uncommon and the most common type of bleeding was gastrointestinal. Whereas PS-matched models showed more bleeding with warfarin compared to no AC, no increase in bleeding events was observed with DOACs. The latter observation was previously shown in two small studies of less than 50 patients CTP A and B patients treated with DOACs, however, direct comparisons are challenging given the variability in the way bleeding rates were reported and the fact that most patients in those studies were treated for thrombotic events rather than for atrial fibrillation.(46, 47) In an exploratory subgroup analysis, we found that DOACs were associated with a 51% lower bleeding risk compared to warfarin. Similar findings were previously reported in a single center study of 85 patients where bleeding occurred in 28% of patients treated with LMWH/Vitamin K antagonists compared to 4% treated with DOACs and need to be further confirmed prospectively.(48)

Limitations

This was a retrospective cohort study with the potential for misclassification bias and residual confounding. Despite our use of advanced causal inference methods to address confounding by indication and time-dependent confounding, differences in unmeasured factors may still be present. For example, we were not able to capture measures of frailty, poor functional status, low engagement with the healthcare system, medication non-adherence or suboptimal social support, which may have impacted both the decision to start anticoagulation and adverse clinical outcomes. As the study sample was predominantly male and Veteran, results may not be generalizable to females or the non-Veteran population. Few patients in the cohort had Child-Pugh C cirrhosis and, therefore, no conclusions regarding safety, efficacy, or bleeding risk with anticoagulation in these patients should be drawn. Although we reported the incidence rates of death after hepatic decompensation, we were limited in our ability ascertain whether anticoagulation was specifically associated with reduced liver-related mortality; this will need to be investigated in future studies. Bleeding events were rare and we were unable to examine the effects of AC on portal hypertensive bleeding versus other gastrointestinal bleeding. Diagnosis codes for GI bleeding have a low positive predictive value in the VA CDW(49); prospective studies should further investigate the effects on AC on specific bleeding complications and portal hypertensive bleeding. Detailed information on portal vein thrombosis regarding extent, chronicity, and patency was unavailable. Although this was a national, multi-center cohort, the sample size of patients prescribed DOACs was relatively limited, precluding comparisons among specific DOAC agents as well as their dosing. These comparisons should be performed in future in-depth pharmacoepidemiologic studies as the clinical experience with DOACs in cirrhosis continues to build.

CONCLUSION

Among veterans with predominantly CTP-A cirrhosis and atrial fibrillation, AC with either warfarin or DOACs was associated with lower all-cause mortality compared to no anticoagulation in a well-matched cohort adjusted for multiple confounders. MSM models showed that hepatic decompensation was reduced with warfarin and DOACs compared to no AC. The incidence of ischemic stroke and MACE was lower with anticoagulation in MSM models. Patients not receiving AC had lower rates of bleeding compared to warfarin in PS-matched models and similar rates of bleeding compared to those on DOACs. Fewer bleeding events were observed with DOACs compared to warfarin in exploratory analyses. Prospective studies should investigate the impact of AC on death, bleeding and thrombotic complications and explore the clinical utility of DOACs in preventing liver-related clinical decompensations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This research was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, award #1K23DK115897-01 and K23-HL133843-04.

Abbreviations:

- AC

anticoagulation

- AUDIT-C

Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test

- BMI

body mass index

- CPT

current procedural terminology

- CTP

Child-Turcotte-Pugh score

- CT

computed tomography

- DOAC

direct oral anticoagulant

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- ICD

international classification of disease

- IQR

interquartile range

- M

mean

- MACE

major adverse cardiovascular events

- MELD

model for end stage liver disease

- MSM

marginal structural model

- NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- PS

propensity score

- SD

standard deviation

- VA

veterans affairs

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record.

Disclosures:

Nothing to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Intagliata NM, Argo CK, Stine JG, Usman T, Caldwell SH, Violi F, et al. Concepts and Controversies in Haemostasis and Thrombosis Associated with Liver Disease: Proceedings of the 7th International Coagulation in Liver Disease Conference. Thromb Haemost. 2018;118(8):1491–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Northup P, Reutemann B. Management of Coagulation and Anticoagulation in Liver Transplantation Candidates. Liver Transplantation. 2018;24(8):1119–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Northup PG, McMahon MM, Ruhl AP, Altschuler SE, Volk-Bednarz A, Caldwell SH, et al. Coagulopathy does not fully protect hospitalized cirrhosis patients from peripheral venous thromboembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(7):1524–8; quiz 680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loffredo L, Pastori D, Farcomeni A, Violi F. Effects of Anticoagulants in Patients With Cirrhosis and Portal Vein Thrombosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(2):480–7 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villa E, Camma C, Marietta M, Luongo M, Critelli R, Colopi S, et al. Enoxaparin prevents portal vein thrombosis and liver decompensation in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1253–60 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinberg EM, Palecki J, Reddy KR. Direct-Acting Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs) in Cirrhosis and Cirrhosis-Associated Portal Vein Thrombosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2019;39(2):195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anstee QM, Dhar A, Thursz MR. The role of hypercoagulability in liver fibrogenesis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35(8–9):526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qamar A, Vaduganathan M, Greenberger NJ, Giugliano RP. Oral Anticoagulation in Patients With Liver Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2162–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuo L, Chao TF, Liu CJ, Lin YJ, Chang SL, Lo LW, et al. Liver Cirrhosis in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Would Oral Anticoagulation Have a Net Clinical Benefit for Stroke Prevention? J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pastori D, Lip GYH, Farcomeni A, Del Sole F, Sciacqua A, Perticone F, et al. Incidence of bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation and advanced liver fibrosis on treatment with vitamin K or non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. Int J Cardiol. 2018;264:58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chokesuwattanaskul R, Thongprayoon C, Bathini T, Torres-Ortiz A, O’Corragain OA, Watthanasuntorn K, et al. Efficacy and safety of anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in patients with cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(4):489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee HF, Chan YH, Chang SH, Tu HT, Chen SW, Yeh YH, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulant and Warfarin in Cirrhotic Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(5):e011112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirley K, Qato DM, Kornfield R, Stafford RS, Alexander GC. National trends in oral anticoagulant use in the United States, 2007 to 2011. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(5):615–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.VA Corporate Data Warehouse. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/vinci/cdw.cfm, Accesed July 26th, 2019.

- 15.Kaplan DE, Dai F, Skanderson M, Aytaman A, Baytarian M, D’Addeo K, et al. Recalibrating the Child-Turcotte-Pugh Score to Improve Prediction of Transplant-Free Survival in Patients with Cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(11):3309–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, Richardson P, Giordano TP, El-Serag HB. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(3):274–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamariz L, Harkins T, Nair V. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying venous thromboembolism using administrative and claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21 Suppl 1:154–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCormick N, Bhole V, Lacaille D, Avina-Zubieta JA. Validity of Diagnostic Codes for Acute Stroke in Administrative Databases: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sohn MW, Arnold N, Maynard C, Hynes DM. Accuracy and completeness of mortality data in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Popul Health Metr. 2006;4:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo Re V 3rd, Lim JK, Goetz MB, Tate J, Bathulapalli H, Klein MB, et al. Validity of diagnostic codes and liver-related laboratory abnormalities to identify hepatic decompensation events in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(7):689–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Floyd JS, Blondon M, Moore KP, Boyko EJ, Smith NL. Validation of methods for assessing cardiovascular disease using electronic health data in a cohort of Veterans with diabetes. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2016;25(4):467–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan DE, Serper MA, Mehta R, Fox R, John B, Aytaman A, et al. Effects of Hypercholesterolemia and Statin Exposure on Survival in a Large National Cohort of Patients With Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(6):1693–706 e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnason T, Wells PS, van Walraven C, Forster AJ. Accuracy of coding for possible warfarin complications in hospital discharge abstracts. Thromb Res. 2006;118(2):253–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulman S, Kearon C, Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the S, Standardization Committee of the International Society on T, Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butt AA, McGinnis K, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Crystal S, Simberkoff M, Goetz MB, et al. HIV infection and the risk of diabetes mellitus. AIDS. 2009;23(10):1227–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. Jama. 2001;285(22):2864–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jepsen P, Vilstrup H, Lash TL. Development and validation of a comorbidity scoring system for patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):147–56; quiz e15-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Archives of internal medicine. 1998;158(16):1789–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan DE, Dai F, Aytaman A, Baytarian M, Fox R, Hunt K, et al. Development and Performance of an Algorithm to Estimate the Child-Turcotte-Pugh Score From a National Electronic Healthcare Database. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(13):2333–41 e1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471–82 e5; quiz e17-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):247–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serper M, Taddei TH, Mehta R, D’Addeo K, Dai F, Aytaman A, et al. Association of Provider Specialty and Multidisciplinary Care With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treatment and Mortality. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(8):1954–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Buuren S, and Groothuis-Oudshoorn K: MICE: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 2011; 45: pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weitzen S, Lapane KL, Toledano AY, Hume AL, Mor V. Principles for modeling propensity scores in medical research: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13(12):841–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen JB, Potluri V, Porrett PM, Chen R, Roselli M, Shults J, et al. Leveraging marginal structural modeling with Cox regression to assess the survival benefit of accepting vs declining kidney allograft offers. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(7):1999–2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cole SR, Hernan MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(6):656–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SR, Lee HJ, Choi EK, Han KD, Jung JH, Cha MJ, et al. Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Liver Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(25):3295–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Done N, Roy AM, Yuan Y, Pizer SD, Rose AJ, Prentice JC. Guideline-concordant initiation of oral anticoagulant therapy for stroke prevention in older veterans with atrial fibrillation eligible for Medicare Part D. Health Services Research. 2019;54(1):128–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barnes GD, Lucas E, Alexander GC, Goldberger ZD. National Trends in Ambulatory Oral Anticoagulant Use. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1300–5 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Girleanu I, Trifan A, Huiban L, Stanciu C. Anticoagulant treatment for atrial fibrillation and decompensation rate in patients with liver cirrhosis, Journal of Hepatology, Volume 68, Supplement 1, April 2018, Page S710. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujii K, Kishiwada M, Hayashi T, Nishioka J, Gabazza EC, Okamoto T, et al. Differential regulation of protein S expression in hepatocytes and sinusoidal endothelial cells in rats with cirrhosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(12):2607–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cerini F, Vilaseca M, Lafoz E, Garcia-lrigoyen O, Garcia-Caldero H, Tripathi DM, et al. Enoxaparin reduces hepatic vascular resistance and portal pressure in cirrhotic rats. J Hepatol. 2016;64(4):834–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vilaseca M, Garcia-Caldero H, Lafoz E, Garcia-lrigoyen O, Avila MA, Reverter JC, et al. The anticoagulant rivaroxaban lowers portal hypertension in cirrhotic rats mainly by deactivating hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2017;65(6):2031–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tripodi A, Primignani M, Chantarangkul V, Mannucci PM. Pro-coagulant imbalance in patients with chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2010;53(3):586–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Intagliata N, Henry Z, Maitland H, Shah N, Argo C, Northup P, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in cirrhosis patients pose similar risks of bleeding when compared to traditional anticoagulation. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2016;61(6):1721–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Gottardi A, Trebicka J, Klinger C, Plessier A, Seijo S, Terziroli B, et al. Antithrombotic treatment with direct-acting oral anticoagulants in patients with splanchnic vein thrombosis and cirrhosis. Liver International. 2017;37(5):694–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hum J, Shatzel JJ, Jou JH, Deloughery TG. The efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants vs traditional anticoagulants in cirrhosis. European journal of haematology. 2017;98(4):393–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Serper M, Kaplan DE, Shults J, Reese PP, Beste LA, Taddei TH, et al. Quality Measures, All-Cause Mortality, and Health Care Use in a National Cohort of Veterans With Cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2019;70(6):2062–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.