Abstract

Objectives

Evaluate penetration of ARVs into compartments and efficacy of a dual, NRTI-sparing regimen in acute HIV infection (AHI).

Design

Single arm, open-label pilot study of participants with AHI initiating ritonavir-boosted darunavir 800 mg once daily plus etravirine 400 mg once daily or 200 mg twice daily within 30 days of AHI diagnosis.

Methods

Efficacy was defined as HIV RNA <200 copies/mL by week 24. Optional sub-studies included PK analysis from genital fluids (weeks 0–4, 12, 48), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (weeks 2–4, 24 and 48) and endoscopic biopsies (weeks 4–12 and 36–48). Neuropsychological performance was assessed at weeks 0, 24 and 48.

Results

Fifteen AHI participants enrolled. Twelve (80%) participants achieved HIV RNA <200 copies/mL by week 24. Among 12 participants retained through week 48, 9 (75%) remained suppressed to <50 copies/mL. The median time from ART initiation to suppression <200 copies/mL and <50 copies/mL was 59 days and 86 days, respectively. The penetration ratios for etravirine and darunavir in gut associated lymphoid tissue were 19.2 and 3.05, respectively. Most AHI participants achieving viral suppression experienced neurocognitive improvement. Of the three participants without overall improvement in neurocognitive functioning as measured by impairment ratings (>2 tests below 1 SD), two had virologic failure.

Conclusion

NRTI-sparing ART started during AHI resulted in rapid viral suppression similar to NRTI-based regimens. More novel and compact two-drug treatments for AHI should be considered. Early institution of ART during AHI appears to improve overall neurocognitive function and may reduce the risk of subsequent neurocognitive impairment.

Keywords: Acute HIV infection, NNRTIs, NRTI-sparing antiretroviral therapy, dual antiretroviral therapy, neurocognitive function, drug penetration

Introduction

Crucial events occur at mucosal surfaces and within tissue compartments very rapidly following HIV acquisition. Due to the high concentration of immune cells in gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), gastrointestinal sites are important targets for HIV replication and pathogenesis, resulting in substantial CD4+ T cell depletion [1, 2]. The very rapid depletion of CD4+ T cells within GALT during acute HIV infection (AHI) likely accounts for the limited efficacy of antiretroviral therapy (ART) to minimize or reverse GALT depletion [3–5]. Similarly, the central nervous system (CNS) is invaded by HIV within days of HIV infection [6]. Recent data suggest that early ART may prevent damage and thus possibly subsequent neurocognitive impairment observed during chronic HIV infection [7]. Whether specific antiretroviral (ARV) medications protect the brain from long-term damage during early infection is unknown; however, the variable penetration of antiretroviral drugs into sanctuary sites may have clinical implications. Similarly, the variable penetration of ART into genital secretions[8] has implications for preventing the high rates of ongoing sexual transmission during AHI. Given limited data to guide the selection of initial ART regimens during AHI, we evaluated the NRTI-sparing regimen of etravirine (ETR) in combination with darunavir boosted with ritonavir (DRV/r) started during AHI, including an evaluation of ARV concentration in GALT, the CNS and genital secretions.

Although not a recommended first line ART regimen, data suggest ETR in combination with DRV/r had comparable antiretroviral activity and potential advantages compared to standard regimens at the time of the study. ETR has activity against wild-type and many transmitted NNRTI-resistant HIV variants and high rates of efficacy among heavily pretreated participants with multiple baseline NNRTI mutations,[9, 10] a benefit given NNRTI resistance remains the most prevalent resistance pattern in the United States (US) and among individuals with AHI in North Carolina [11–15]. In a study of once daily ETR with co-formulated tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) in treatment naïve, chronically HIV-infected participants, 77% achieved viral suppression by week 48 [16]. The ACTG 5142 study demonstrated equivalence of a NNRTI plus a ritonavir-boosted PI regimen versus standard ART [17]. Based on the low prevalence of resistance-associated mutations with PIs and particularly DRV, PI-based regimens have been recommended for treatment during AHI and prior to availability of resistance testing results[18]. In sum, available data demonstrated antiviral activity for a ritonavir-boosted PI in combination with ETR comparable to standard first-line ART regimens with the potential advantage of a higher threshold for HIV resistance with both DRV and ETR.

These data in combination with advances in ARVs led to the recent exploration of novel dual therapy regimens for the treatment of chronic HIV infection [19–23]. However, to our knowledge, no dual therapy regimen has been studied in the setting of acute HIV. We evaluated the safety, tolerability and activity of the dual NRTI-sparing ART regimen of DRV/r combined with ETR initiated in AHI. We evaluated viral decline and characterized pharmacokinetics (PK) in plasma and tissue compartments including GALT, CSF and genital secretions and sought to assess the impact of early treatment with this dual regimen on neurocognitive function.

Methods

ART-naïve participants ≥18 years of age diagnosed with AHI within 30 days of enrollment were eligible. AHI diagnosis was the date of sample collection for the first test detecting HIV, not the date the individual was notified of the result. ART naïve was defined as ≤14 days of ART prior to study entry except for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) if HIV negative within 6 months after completing PEP. AHI was defined as: i) negative ELISA immunoassay (EIA) and positive nucleic acid testing (NAT); ii) positive EIA and positive NAT with a negative/indeterminate western blot; or iii) positive EIA, positive western blot and EIA negative documentation within the preceding 30 days. Participants were referred with results suggestive of AHI from the community or from routine screening for AHI performed at the North Carolina (NC) State Laboratory of Public Health with Genetic Systems HIV-1/HIV-2 Plus 0 EIA, Bio-Rad Laboratories (Redmond, Washington), Bio-Rad Genetic Systems HIV-1 Western Blot and Aptima HIV-1 RNA Qualitative Assay (Gen-Probe Inc., San Diego, California) pooling of seronegative samples [24] until November 2013; thereafter with Chemiluminescent Microparticle Immunoassay (CMIA) assay and the Multispot HIV-1/HIV-2 rapid test, Bio-Rad Laboratories. HIV testing at enrollment was as follows: i) 2009 to 11/2010 with Genetic Systems HIV-1/HIV-2 Plus O EIA with Genetic Systems HIV-1 Western blot, Bio-Rad Laboratories, ii) 12/2010 to 3/2012 with Abbott Architect HIV Ag/Ab Combo Assay with Bio-Rad Genetic Systems HIV-1 Western Blot, and iii) 3/2012 onward with Abbott Architect HIV Ag/Ab Combo Assay and Bio-Rad Multispot HIV-1/HIV-2 Rapid Test. AHI referrals to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) and Duke University were offered prompt evaluation, usually within 1–2 days [25, 26]. Exclusion criteria were minimal and included pregnancy, breastfeeding, inability to commit to acceptable methods to avoid pregnancy, incarceration, recent administration of immunomodulating medications, serious acute or psychiatric illness or chronic hepatitis B infection.

In this dual-center, single-arm, open-label pilot study, participants with AHI were administered and started darunavir 800 mg once daily, ritonavir 100 mg once daily and etravirine either as 400 mg once daily or 200 mg twice daily at enrollment. Baseline resistance testing was performed on all participants. Participants were evaluated at weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, 36 and 48. Virologic failure was defined as failure to achieve HIV-1 RNA <200 copies/mL by week 24 or 2 consecutive HIV-1 RNA levels >200 copies/mL at least one week apart after week 24. Adherence was assessed by self-report. Date of symptom onset consistent with acute HIV infection was documented. Adverse events were graded according to the Division of AIDS Table for Grading the Severity of Adult and Pediatrics Adverse Events, Version 1.0, December 2004; Clarification August 2009.

Pharmacokinetic (PK) Sampling

Blood samples were collected for an abbreviated PK analysis with samples taken pre-dose and then at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 15–24 hours after an observed dose at weeks 4 and 48, and for storage at each visit. Optional sub-studies included sample collection for PK analysis from: i) genital fluids (between weeks 0–4, and weeks 12 and 48), ii) CSF (between week 2–4, and at weeks 24 and 48), iii) endoscopic biopsies (between weeks 4–12 and between weeks 36–48). Genital secretions were self-collected following a 48-hour period of reported sexual abstinence and CSF was collected via standard lumbar puncture procedures. Endoscopic biopsies were obtained by colonoscopy from the terminal ileum; biopsy specimens weighed an average of 50 mg and were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after collection. All samples were stored at −80°C. Concentrations were quantified in matrices per previously published methods [27].

Neurocognitive Testing

Neuropsychological performance was assessed at baseline (week 2 or 4), week 24 and week 48 in the following domains (measures): Premorbid/language (Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT) 4 - Reading Subtest (Wilkinson, 1993)), Learning (HVLT-R, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised, (Benedict et al., 1998)), Memory (HVLT-R), Speed of Processing (Trailmaking A (Army Individual Test Battery, 1944; Reitan and Davison)), 1974, Stroop color (Stroop, 1935; Kaplan adaptation of Comalli)), Attention (WAIS-III Symbol Search (Psychological Corporation, 1997); Stroop word, (Stroop,1935);) Fine motor (Grooved pegboard, Kløve, 1963), Executive (Trailmaking B, Stroop interference, Letter, Category Fluency (Gladsjo et al., 1999)). An overall summary score of neurocognitive functioning was created by averaging all tests. Participants completed the self-reported functional status. Patient’s Assessment of Own Functioning Inventory (PAOFI) (Chelune, Heaton, and Lehman, 1986) and the Activities of Daily Living Scale (ADLS) (Lawton & Brody, 1969). Best available demographically corrected normative data were utilized to create z-scores and then deficit scores for impairment ratings.

The institutional review boards at UNC and Duke University approved the study. All study participants provided written informed consent and a separate informed consent before each optional procedure.

Statistical Analysis

We examined demographic and clinical characteristics of participants using descriptive statistics. Time to viral suppression was calculated as the number of days from ART initiation until the first documented HIV RNA <200 copies/mL and the first documented HIV RNA value <50 copies/mL. Exposures included baseline HIV RNA level and duration from estimated-date-of-infection[28, 29] until treatment. Each exposure was dichotomized into those less than or equal to the median value and those above the median value. For the time to viral suppression analysis, participants were censored if they stopped treatment or were lost to follow-up before demonstrating viral suppression prior to week 24. Log-rank test was used to assess differences in suppression times between exposure groups. Multivariable proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios for the association between baseline HIV RNA level and time to viral suppression. Potential confounders included CD4+ T cell count and age. The final model was built using backwards elimination with a 10% change in estimate criteria for retaining confounding variables.

Compartment penetration ratio (matrix:plasma) was calculated by division of CSF (ng/mL), semen (ng/mL), and tissue concentrations (ng/g converted to ng/mL using a tissue density correction) with plasma concentrations (ng/mL). Samples taken within the same dosing interval were considered paired. If there were multiple plasma samples, then the sample taken closest in time to the compartment sample was chosen. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Change in neurocognitive functioning was analyzed using a repeated measures ANOVA with neurocognitive performance as the dependent variable (total z-score) and time (visit) as the independent variable. Correlation between CD4+ nadir, baseline HIV RNA level and time to viral suppression with total z-score was assessed by Spearman correlation.

Results

Between August 2009 and November 2012, 15 participants with AHI enrolled and started the study regimen. Baseline characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. The median age was 24 years (range 19 – 51). Eleven participants (74%) were African American, 3 (20%) Hispanic white and 1 (6.7%) non-Hispanic white. The majority (n= 13; 87%) of participants were men who have sex with men (MSM) as only 2 (13%) female participants enrolled; no male participants self-identified as heterosexual. Among 13 MSM enrolled, 12 (92%) were less than 30 years of age; both female participants were aged >30 years. No potential participants were excluded from enrollment. Eleven (85%) participants were enrolled following AHI detection at the NC State Laboratory of Public Health.

Table 1.

Demographic/clinical characteristics of participants starting ART in acute HIV

| AHI Participants n = 15 | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 24 (19–51) |

| Sexual risk group | |

| Female | 2 (13.3) |

| Heterosexual male | 0 (0.0) |

| Men who have sex with men | 13 (86.7) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 1 (6.7) |

| White, Hispanic | 3 (20.0) |

| African American | 11 (73.3) |

| HIV RNA level | |

| Initial | 1,000,000 (22,858 – 29,807,640) |

| Peak observeda | 1,156,070 (22,858 – 160,000,000) |

| CD4 T cell count (cells/mm3) | |

| Baseline CD4 T cell count | 629 (268–1133) |

| Nadir CD4 T cell count | 501 (268 – 838) |

| Time to treatment and suppression (days) | |

| Estimated date of infection to ART start | 44 (23 – 140) |

| Diagnosis to ART start | 22 (9 – 28) |

| ART start to HIV RNA level <200 copies/mL | 59 (15 – 489) |

| ART start to HIV RNA level <50 copies/mL | 86 (15–489) |

Data presented as n (%) or median (range).

Peak HIV RNA levels prior to study enrollment were included when available.

Prior to starting ART, the median HIV RNA level was 1,000,000 copies/ml (range 22,858– 29,807,640), and the median nadir CD4+ T cell count was 501 cells/mm3 (range 268–838.) Based on the date of symptom onset (assumed infection to be 14 days prior based on prior analyses[28],) we estimated participants initiated ART at a median of 44 days (range 23 – 140) after acquiring HIV,[28, 29] and all had seroconverted at the time of starting ART. Genotype testing revealed a mutation (E138A) associated with resistance to study treatment in only one participant at baseline. He was lost to follow-up early following entry.

The treatment regimen was well-tolerated with a total of five adverse events (AEs) in four participants that were attributed as possibly/definitely related to study treatment. All were Grade 1 and included nausea, rash, headache, dizziness, and increase in cholesterol. All treatment-related AEs resolved spontaneously without intervention and occurred as one-time events. No study treatment doses were held, and no participants discontinued study treatment due to an AE.

Forty percent (n=6/15) of participants had a CD4+ nadir <400 cells/mm3, with a median increase in CD4+ T cell count of 158 cells/mm3 (range 281–916) and 349 cells/mm3 (range 7–495) from baseline to week 24 and week 48, respectively. Twelve of 15 (80%) participants suppressed to <200 copies/mL prior to or at week 24. Among three study-defined treatment failures at week 24, one participant was lost to follow-up (LTFU) after week 2, and two participants had low level viremia (283 copies/mL and 226 copies/mL), one of whom suppressed at week 36 and the other participant was discontinued from the trial due to poor adherence.

Overall, LTFU was minimal; 14 (93%) participants completed a study visit at or after week 36 and 12 (80%) completed a week 48 study visit. Among the 12 participants retained through week 48, nine (75%) demonstrated viral suppression <50 copies/mL. Among three viremic participants at week 48, two participants had low level viremia (96 and 71 copies/mL), and the third viremic participant had prior durable HIV RNA suppression but discontinued study treatment due to preference for a one pill once-a-day regimen after week 24. The overall median time from starting ETR + DRV/r to HIV RNA suppression <200 copies/mL was 59 days (range 15–489) and to <50 copies/mL was 86 days (range 15–489).

Pharmacokinetics

For the optional procedures, six participants provided paired ileal biopsy samples, four participants provided seven CSF samples, and six participants provided semen samples. HIV RNA was not detected in any CSF samples and HIV RNA was detected in ilieal biopsy specimens from three of six participants only at the first measurement. Median ARV plasma exposures with the interquartile ranges are shown in Figure 1. ARV exposures varied between biological matrices. DRV and ETR concentrations and area under the curve (AUC) values at 12 hours were extrapolated through non-compartmental analyses for the ileum and semen (data not shown), and these agreed well with literature values [27]. ETR exposure ranged from 4–25ng/mL in CSF, 12–185 ng/mL in semen, and 1,317–98,293 ng/g in ileal tissue. DRV exposure ranged from 10–240 ng/mL in CSF, 9–1,296 ng/mL in semen, and 987–202,815 ng/g in ileal tissue. Of the three ARVs, compared to paired plasma sample concentrations, ETR had the highest penetration into the CSF (1.6% of plasma concentrations, Table 2) and into GALT (1920% of plasma concentrations), while DRV had the highest penetration into semen (16.2% of plasma concentrations). Ileal tissue concentrations of all antiretrovirals exceeded accompanying plasma concentrations by 19.2-fold (ETR) and 3-fold (DRV).

Figure 1.

Plasma, CSF, semen, and tissue, concentrations of ETR and DRV over time after dose (hours). Solid line represents the observed median plasma concentration and the dashed lines represent the 25th and 75th percentiles around the median. Yellow squares represent CSF concentrations, blue diamonds represent seminal concentrations, green triangles represent ileal concentrations. ETR, etravirine; DRV, darunavir.

Table 2.

Penetration Ratios; median (min-max); number of pairings

| Drug | CSF | Semen | Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|

| ETR | 0.016 (0.003–0.075); 6 | 0.121 (0.008–0.181); 7 | 19.2 (2.46–117); 6 |

| DRV | 0.007 (0.001–0.129); 7 | 0.162 (0.002–0.189); 6 | 3.05 (0.024–32.4); 6 |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; DRV, darunavir; ETR, etravirine.

Neurocognitive Testing

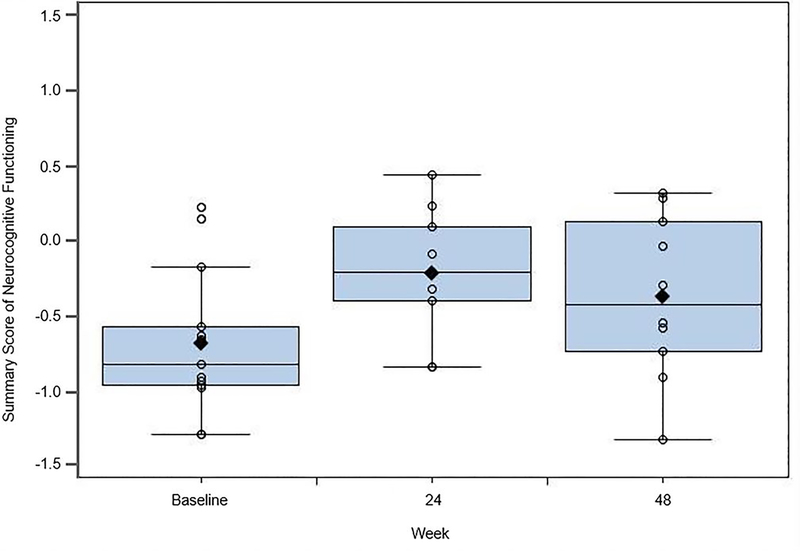

Thirteen of 15 (87%) participants had baseline neurocognitive assessments, and 11 participants had subsequent assessments at week 24 and/or 48 after ART initiation; eight participants completed assessments at all three time points. At baseline, 61% of participants were considered impaired (defined as more than 2 tests >1 standard deviation (SD) below the norm), 33% were impaired at 24 weeks and 30% impaired at 48 weeks. There was a statistically significant improvement in overall neurocognitive functioning over time (F(2,17)= 4.23, p= 0.03), with the greatest improvement occurring between baseline and week 24 (baseline mean z =−0.69, (.14), week 24 mean z=−0.40 (.15), and week 48 mean z=−45 (.15)) (Figure 2). Two of the three participants who did not experience neurocognitive improvement failed to achieve virologic suppression. Self-report of current cognitive or physical problems at baseline was noted in 23%, but there was no association with overall neuropsychological performance (r=−.22, ns). There was no correlation with CD4+ nadir and total z-score (r=.19, ns) for neuropsychological performance impairment, although the median CD4+ nadir was high at 501 cells/mm3 (range 268–838). More rapid HIV RNA suppression was significantly correlated with improved neurocognitive performance (r = −.82, p<.005) (Figure 3A). Higher baseline HIV RNA was associated with poorer neurocognitive performance at week 48 (r = −.67, p.05) (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Neurocognitive function at baseline and following ART initiation in acute HIV infection.

Figure 3.

Time to HIV suppression following treatment in acute HIV infection and neurocognitive function. Panel A shows that more rapid HIV RNA suppression was significantly correlated with improved neurocognitive performance (r = −.82, p<.005). Panel B demonstrates that a higher baseline HIV RNA was associated with poorer neurocognitive performance at week 48 (r = −.67, p.05).

Discussion

At the time this study was initiated, ART treatment guidelines considered treatment during AHI optional due to lack of data confirming clinical benefit[30]. In 2013, guidelines were updated to recommend the immediate initiation of ART during AHI due to expanding data on the ability of ART during AHI to preserve immune function, decrease the HIV RNA set point [31–33], reduce the size of the latent HIV reservoir [34–37], and limit viral diversity due to the suppression of viral mutations [38, 39]. We sought to assess the activity of a dual, NRTI-sparing ART regimen started during AHI, and to explore whether the pharmacokinetics of this regimen might offer advantages with regards to GALT and CSF penetration.

The regimen was generally well-tolerated and despite a higher pill burden, only one participant stopped treatment due to a preference for a single tablet regimen. Viral suppression rates were comparable to recommended ART regimens at the time of the study; 80% by week 24 and 75% of those retained through week 48. Lower rates of suppression may in part reflect the impact of lost to follow-up given the small sample size. Limitations of the study include the small sample size and lack of a comparison arm, precluded by the infrequent diagnosis of acute HIV. Both prevent concluding this regimen is equivalent in efficacy to past or current standard ART; however, the findings are notable given the expansion of dual therapy for chronic HIV and its use during AHI in our study.

Time to viral suppression <50 copies/mL for the 2-drug regimen of DRV/r + ETR in AHI (median 86 days) was shorter than that observed in an earlier study using coformulated FTC/TDF/efavirenz (median 102 days) [14]. In comparison, in a chronically infected patients suppressed to <50 copies/mL at a median of 60 days with integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTI), 137 days with NNRTI regimens and 147 days with PI regimens[40]. In addition, our results compare favorably with results from other studies on treatment-naïve participants treated with DRV/r-containing triple drug regimens (Supplemental Figure 1)[41, 42].

These results suggest that a PI-based, NRTI-sparing 2-drug ART regimen started during AHI has potent activity, even in the setting of high HIV RNA typical of individuals diagnosed early. The recent FDA approval of 2-drug integrase inhibitor-based ART with dolutegravir and rilpivirine, although only for patients with HIV RNA suppression, suggest the potency of current antiretroviral drugs may support treatment with NRTI-sparing regimens as a long term strategy. Additional 2-drug ART regimens have been FDA approved for ART treatment-naïve participants (dolutegravir and lamivudine) and others are under evaluation (cabotegravir and rilpivirine). However, data on these dual regimens as initial therapy during AHI is not yet available, and current guidelines recommend either boosted DRV or DTG in combination with 2 NRTIs if started before drug resistance testing results are available [30].

Penetration ratios of ETR (19.2) and DRV (3) observed in GALT at least suggest these ARVs could favorably minimize GALT depletion or allow early recovery in AHI. These GALT penetration ratios are consistent with previously published rectal concentrations [27]. As expected, drug concentrations in CSF and semen were low compared to plasma and are consistent with previously published concentration ranges[27, 43, 44]. A limitation of this analysis is that we quantified total drug concentrations, since it has been demonstrated that unbound concentrations of efavirenz are equivalent between plasma and CSF [45], although DRV is chiefly unbound in CSF [46] However, our previous understanding of minimal protein binding potential in semen and the ileum indicates that the majority of the measured concentration of drug is available for activity against HIV in these matrices [27, 47]. All of these concentrations were at least several-fold above the protein-adjusted IC50 of the virus.

Additionally, our findings suggest that early initiation of ART may improve neurocognitive performance. Other studies have also demonstrated neurocognitive impairment in individuals with early or acute HIV [48, 49]. Data from studies on whether ART in acute HIV improved neurocognitive performance have been inconclusive, in part due to variation in the timing of ART initiation in acute or early HIV and prevalence of substance abuse [48, 49]. In our study, 61% of individuals with AHI demonstrated neurocognitive impairment at baseline, and in most, neuropsychological performance improved during 24 and 48 weeks of treatment. However, 2 of 3 participants who met study criteria for virologic failure demonstrated persistent neurocognitive impairment. While psychological distress of HIV infection was noted in some, there was no significant relationship to neuropsychological performance. However, higher baseline HIV RNA correlated with poorer neurocognitive outcome at week 48 and more rapid HIV RNA suppression correlated with improved neurocognitive outcome at week 48. The lack of a control group and the small sample size preclude ruling out other causes, but this data suggests that treatment during AHI may improve neurocognitive function, a plausible finding given the rapidity with which HIV virus enters the CNS following HIV infection[6, 50] and persistent neurocognitive impairment observed despite viral suppression[51, 52]. Accordingly, very early effective ART in AHI may improve or preserve neurocognitive function by suppressing viremia within the CNS and limiting CD4+ nadir, as the latter has been associated with the risk for neurocognitive impairment [7, 49].

Conclusion

In summary, among participants with acute HIV infection, this 2-drug, NRTI-sparing ART regimen of DRV/r plus ETR demonstrated comparable activity to standard ART, favorable drug concentrations in GALT and improvements in neurocognitive impairment. As coformulation options expand, additional and larger studies of other dual regimens for treatment naïve patients, as well as the uptake and experience of dual regimens for maintenance therapy, are needed to fully elucidate the role of dual ART during AHI. Although this regimen in unlikely to be used given current guidelines recommending effective, co-formulated options, our findings contribute to expanding data on dual ART, as well as dual ART and NRTI-sparing regimens in acute HIV infection, and tissue penetration of ARVs.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. HIV RNA suppression rates across naïve treatment studies with boosted darunavir and etravirine.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the support of all study staff members, HIV care providers, staff in the UNC and Duke Infectious Diseases clinics and particularly the individuals who participated in this study. We also acknowledge and remember our very good friend and talented colleague, Kevin Robertson, who passed prior to publication of these results.

Sources of Funding: This research was supported by the generous contributions of: Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, the UNC Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) (P30AI 50410), the Duke University CFAR (5P30 AI064518), grant (R01 A01050483), grant (RR00046) from the Clinical Trials Research Center program of the Division of Research Resources, and in part by funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (T32 HD52468).

Financial Disclosure: This study is supported by the generous contributions of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC and the following NIH funded programs: the UNC Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) (P30 AI50410), the Duke CFAR (5P30 AI064518), a grant (RR00046) from the General Clinical Research Centers program of the Division of Research Resources, and a 2K24 AI01608 award. A.S.D. is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH under Award Number T32GM086330. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of National Institutes of Health. Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC provided antiretroviral medications for this study. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: C.G. has received research support from Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Abbott, Janssen, and ViiV Healthcare. C.H. has received grant support and/or consulting/honoraria from BMS, GSK, Merck, Tibotec Therapeutics and Gilead, and is a full time employee at Viiv Healthcare. D.M. has consulted for Merck and Viiv Healthcare, and holds common stock in Gilead Sciences. J.E. receives research support from ViiV Healthcare, Gilead, and Janssen and is a consultant to Merck, Gilead, Janssen, ViiV Healthcare. MM has received research support from Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, and ViiV Healthcare. A.S.D., A.D.M.K., D.N., G. F., J.K., J.S., J.S., K.M., N.S., S.F., K.R.R- No conflicts.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Dandekar S Pathogenesis of HIV in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2007; 4(1):10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Q, Duan L, Estes JD, Ma ZM, Rourke T, Wang Y, et al. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature 2005; 434(7037):1148–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehandru S, Poles MA, Tenner-Racz K, Jean-Pierre P, Manuelli V, Lopez P, et al. Lack of mucosal immune reconstitution during prolonged treatment of acute and early HIV-1 infection. PLoS Med 2006; 3(12):e484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tincati C, Biasin M, Bandera A, Violin M, Marchetti G, Piacentini L, et al. Early initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy fails to reverse immunovirological abnormalities in gut-associated lymphoid tissue induced by acute HIV infection. Antivir Ther 2009; 14(3):321–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ananworanich J, Schuetz A, Vandergeeten C, Sereti I, de Souza M, Rerknimitr R, et al. Impact of multi-targeted antiretroviral treatment on gut T cell depletion and HIV reservoir seeding during acute HIV infection. PLoS One 2012; 7(3):e33948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valcour V, Chalermchai T, Sailasuta N, Marovich M, Lerdlum S, Suttichom D, et al. Central nervous system viral invasion and inflammation during acute HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2012; 206(2):275–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peluso MJ, Ananworanich J, Sithinamsuwan P, Slike B, Gisslen M, Zetterberg H, et al. Immediate Antiretroviral Therapy Mitigates the Development of Neuronal Injury in Acute HIV, Abstract 31. In: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections Boston, MA; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trezza CR, Kashuba AD. Pharmacokinetics of antiretrovirals in genital secretions and anatomic sites of HIV transmission: implications for HIV prevention. Clin Pharmacokinet 2014; 53(7):611–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madruga JV, Cahn P, Grinsztejn B, Haubrich R, Lalezari J, Mills A, et al. Efficacy and safety of TMC125 (etravirine) in treatment-experienced HIV-1-infected patients in DUET-1: 24-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 370(9581):29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazzarin A, Campbell T, Clotet B, Johnson M, Katlama C, Moll A, et al. Efficacy and safety of TMC125 (etravirine) in treatment-experienced HIV-1-infected patients in DUET-2: 24-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 370(9581):39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett DE, Camacho RJ, Otelea D, Kuritzkes DR, Fleury H, Kiuchi M, et al. Drug resistance mutations for surveillance of transmitted HIV-1 drug-resistance: 2009 update. PLoS One 2009; 4(3):e4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanik EL, Napravnik S, Hurt CB, Dennis A, Quinlivan EB, Sebastian J, et al. Prevalence of transmitted antiretroviral drug resistance differs between acutely and chronically HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 61(2):258–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snedecor SJ, Khachatryan A, Nedrow K, Chambers R, Li C, Haider S, et al. The prevalence of transmitted resistance to first-generation non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and its potential economic impact in HIV-infected patients. PLoS One 2013; 8(8):e72784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gay CL, Willis SJ, Cope AB, Kuruc JD, McGee KS, Sebastian J, et al. Fixed-dose combination emtricitabine/tenofovir/efavirenz initiated during acute HIV infection; 96-week efficacy and durability. AIDS 2016; 30(18):2815–2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levintow SN, Okeke NL, Hue S, Mkumba L, Virkud A, Napravnik S, et al. Prevalence and Transmission Dynamics of HIV-1 Transmitted Drug Resistance in a Southeastern Cohort. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018; 5(8):ofy178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Floris-Moore MA, Mollan K, Wilkin AM, Johnson MA, Kashuba AD, Wohl DA, et al. Antiretroviral activity and safety of once-daily etravirine in treatment-naive HIV-infected adults: 48-week results. Antivir Ther 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mugavero MJ, May M, Ribaudo HJ, Gulick RM, Riddler SA, Haubrich R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of initial antiretroviral therapy regimens: ACTG 5095 and 5142 clinical trials relative to ART-CC cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 58(3):253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adolescents. PoAGfAa. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services; In; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soriano V, Fernandez-Montero JV, Benitez-Gutierrez L, Mendoza C, Arias A, Barreiro P, et al. Dual antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2017; 16(8):923–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Llibre JM, Hung CC, Brinson C, Castelli F, Girard PM, Kahl LP, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of dolutegravir-rilpivirine for the maintenance of virological suppression in adults with HIV-1: phase 3, randomised, non-inferiority SWORD-1 and SWORD-2 studies. Lancet 2018; 391(10123):839–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cahn P, Madero JS, Arribas JR, Antinori A, Ortiz R, Clarke AE, et al. Dolutegravir plus lamivudine versus dolutegravir plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection (GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2): week 48 results from two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trials. Lancet 2019; 393(10167):143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taiwo BO, Zheng L, Stefanescu A, Nyaku A, Bezins B, Wallis CL, et al. ACTG A5353: A pilot study of dolutegravir plus lamivudine for initial treatment of HIV-1-infected participants with HIV-1 RNA < 500,000 copies/mL. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 8;66(11):1689–1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Figueroa MI, Sued OG, Gun AM, Belloso W, Cecchini DM, Lopardo G, et al. DRV/R/3TC FDC for HIV-1 Treatment Naive Patients: Week 48 Results of the ANDES Study. In: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections March 4–7, Boston, MA; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pilcher CD, Fiscus SA, Nguyen TQ, Foust E, Wolf L, Williams D, et al. Detection of acute infections during HIV testing in North Carolina. N Engl J Med 2005; 352(18):1873–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKellar MS, Cope AB, Gay CL, McGee KS, Kuruc JD, Kerkau MG, et al. Acute HIV-1 infection in the Southeastern United States: a cohort study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013; 29(1):121–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuruc JD, Cope AB, Sampson LA, Gay CL, Ashby RM, Foust EM, et al. Ten Years of Screening and Testing for Acute HIV Infection in North Carolina. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 71(1):111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown KC, Patterson KB, Jennings SH, Malone SA, Shaheen NJ, Asher Prince HM, et al. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of darunavir plus ritonavir and etravirine in semen and rectal tissue of HIV-negative men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 61(2):138–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gay C, Dibben O, Anderson JA, Stacey A, Mayo AJ, Norris PJ, et al. Cross-Sectional Detection of Acute HIV Infection: Timing of Transmission, Inflammation and Antiretroviral Therapy. PLoS One 2011; 6(5):e19617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindback S, Thorstensson R, Karlsson AC, von Sydow M, Flamholc L, Blaxhult A, et al. Diagnosis of primary HIV-1 infection and duration of follow-up after HIV exposure. Karolinska Institute Primary HIV Infection Study Group. AIDS 2000; 14(15):2333–2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. PoAGfAa. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. In. Edited by Services Department of Health and Human Services; 2019.

- 31.Hogan CM, Degruttola V, Sun X, Fiscus SA, Del Rio C, Hare CB, et al. The setpoint study (ACTG A5217): effect of immediate versus deferred antiretroviral therapy on virologic set point in recently HIV-1-infected individuals. J Infect Dis 2012; 205(1):87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamlyn E, Ewings FM, Porter K, Cooper DA, Tambussi G, Schechter M, et al. Plasma HIV viral rebound following protocol-indicated cessation of ART commenced in primary and chronic HIV infection. PLoS One 2012; 7(8):e43754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grijsen ML, Steingrover R, Wit FW, Jurriaans S, Verbon A, Brinkman K, et al. No treatment versus 24 or 60 weeks of antiretroviral treatment during primary HIV infection: the randomized Primo-SHM trial. PLoS Med 2012; 9(3):e1001196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gianella S, von Wyl V, Fischer M, Niederost B, Joos B, Gunthard H, et al. Impact of early ART on proviral HIV-1 DNA and plasma viremia in acutely infected patients. In: 17th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections San Francisco, CA; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hocqueloux L, Prazuck T, Avettand-Fenoel V, Lafeuillade A, Cardon B, Viard JP, et al. Long-term immunovirologic control following antiretroviral therapy interruption in patients treated at the time of primary HIV-1 infection. AIDS 2010; 24(10):1598–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmid A, Gianella S, von Wyl V, Metzner KJ, Scherrer AU, Niederost B, et al. Profound depletion of HIV-1 transcription in patients initiating antiretroviral therapy during acute infection. PLoS One 2010; 5(10):e13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strain MC, Little SJ, Daar ES, Havlir DV, Gunthard HF, Lam RY, et al. Effect of treatment, during primary infection, on establishment and clearance of cellular reservoirs of HIV-1. J Infect Dis 2005; 191(9):1410–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goonetilleke N, Liu MK, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Ferrari G, Giorgi E, Ganusov VV, et al. The first T cell response to transmitted/founder virus contributes to the control of acute viremia in HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med 2009; 206(6):1253–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McMichael AJ, Borrow P, Tomaras GD, Goonetilleke N, Haynes BF. The immune response during acute HIV-1 infection: clues for vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol 2010; 10(1):11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacobson K, Ogbuagu O. Integrase inhibitor-based regimens result in more rapid virologic suppression rates among treatment-naive human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients compared to non-nucleoside and protease inhibitor-based regimens in a real-world clinical setting: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97(43):e13016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishijima T, Komatsu H, Teruya K, Tanuma J, Tsukada K, Gatanaga H, et al. Once-daily darunavir/ritonavir and abacavir/lamivudine versus tenofovir/emtricitabine for treatment-naive patients with a baseline viral load of more than 100 000 copies/ml. AIDS 2013; 27(5):839–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gazzard B, Duvivier C, Zagler C, Castagna A, Hill A, van Delft Y, et al. Phase 2 double-blind, randomized trial of etravirine versus efavirenz in treatment-naive patients: 48-week results. AIDS 2011; 25(18):2249–2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yilmaz A, Izadkhashti A, Price RW, Mallon PW, De Meulder M, Timmerman P, et al. Darunavir concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid and blood in HIV-1-infected individuals. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2009; 25(4):457–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tiraboschi JM, Niubo J, Ferrer E, Barrera-Castillo G, Rozas N, Maso-Serra M, et al. Etravirine concentrations in seminal plasma in HIV-infected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68(1):184–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Avery LB, Sacktor N, McArthur JC, Hendrix CW. Protein-free efavirenz concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid and blood plasma are equivalent: applying the law of mass action to predict protein-free drug concentration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57(3):1409–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Croteau D, Rossi SS, Best BM, Capparelli E, Ellis RJ, Clifford DB, et al. Darunavir is predominantly unbound to protein in cerebrospinal fluid and concentrations exceed the wild-type HIV-1 median 90% inhibitory concentration. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68(3):684–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown KC, Patterson KB, Malone SA, Shaheen NJ, Prince HM, Dumond JB, et al. Single and multiple dose pharmacokinetics of maraviroc in saliva, semen, and rectal tissue of healthy HIV-negative men. J Infect Dis 2011; 203(10):1484–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kore I, Ananworanich J, Valcour V, Fletcher JL, Chalermchai T, Paul R, et al. Neuropsychological Impairment in Acute HIV and the Effect of Immediate Antiretroviral Therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 70(4):393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spudich S HIV and neurocognitive dysfunction. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2013; 10(3):235–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pilcher CD, Shugars DC, Fiscus SA, Miller WC, Menezes P, Giner J, et al. HIV in body fluids during primary HIV infection: implications for pathogenesis, treatment and public health. AIDS 2001; 15(7):837–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peluso MJ, Meyerhoff DJ, Price RW, Peterson J, Lee E, Young AC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and neuroimaging biomarker abnormalities suggest early neurological injury in a subset of individuals during primary HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2013; 207(11):1703–1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robertson KR, Smurzynski M, Parsons TD, Wu K, Bosch RJ, Wu J, et al. The prevalence and incidence of neurocognitive impairment in the HAART era. AIDS 2007; 21(14):1915–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. HIV RNA suppression rates across naïve treatment studies with boosted darunavir and etravirine.