Abstract

Introduction

Direct emissions of nicotine and harmful chemicals from electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) have been intensively studied, but secondhand and thirdhand e-cigarette aerosol (THA) exposures in indoor environments are understudied.

Aims and Methods

Indoor CO2, NO2, particulate matter (PM2.5), aldehydes, and airborne nicotine were measured in five vape-shops to assess secondhand exposures. Nicotine and tobacco-specific nitrosamines were measured on vape-shop surfaces and materials (glass, paper, clothing, rubber, and fur ball) placed in the vape-shops (14 days) to study thirdhand exposures.

Results

Airborne PM2.5, formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and nicotine concentrations during shop opening hours were 21, 3.3, 4.0, and 3.8 times higher than the levels during shop closing hours, respectively. PM2.5 concentrations were correlated with the number of e-cigarette users present in vape-shops (ρ = 0.366–0.761, p < .001). Surface nicotine, 4-(N-methyl-N-nitrosamino)-4-(3-pyridyl)butanal (NNA), and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) were also detected at levels of 223.6 ± 313.2 µg/m2, 4.78 ± 11.8 ng/m2, and 44.8 ± 102.3 ng/m2, respectively. Substantial amounts of nicotine (up to 2073 µg/m2) deposited on the materials placed within the vape-shops, and NNA (up to 474.4 ng/m2) and NNK (up to 184.0 ng/m2) were also formed on these materials. The deposited nicotine concentrations were strongly correlated with the median number of active vapers present in a vape-shop per hour (ρ = 0.894–0.949, p = .04–.051). NNK levels on the material surfaces were significantly associated with surface nicotine levels (ρ=0.645, p = .037).

Conclusions

Indoor vaping leads to secondhand and THA exposures. Thirdhand exposures induced by e-cigarette vaping are comparable or higher than that induced by cigarette smoking. Long-term studies in various microenvironments are needed to improve our understanding of secondhand and THA exposures.

Implications

This study adds new convincing evidence that e-cigarette vaping can cause secondhand and THA exposures. Our findings can inform Occupational Safety and Health Administration, state authorities, and other government agencies regarding indoor air policies related to e-cigarette use, particularly in vape-shops. There is an urgent need to ensure that vape-shops maintain suitable ventilation systems and cleaning practices to protect customers, employees, and bystanders. Our study also demonstrates that nicotine can deposit or be adsorbed on baby’s clothes and toys, and that tobacco-specific nitrosamines can form and retain on baby’s clothes, highlighting children’s exposure to environmental e-cigarette aerosol and THA at home is of a particular concern.

Introduction

Direct emissions of nicotine and harmful chemicals (eg, formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acrolein) from electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) have been studied by many researchers,1–7 but there is a paucity of research on e-cigarettes’ impact on indoor environmental quality.8 Environmental tobacco smoke, generated via exhaled or side-stream conventional cigarette smoke, exposes users and bystanders to nicotine and harmful chemicals such as aldehydes.9 Similarly, the increasing popularity of e-cigarettes and its indoor use could be another source of passive nicotine and harmful chemical exposures in indoor environments.10 Since e-cigarettes do not generate side-stream smoke like conventional cigarettes, exhaled e-cigarette aerosol is the only source of environmental e-cigarette aerosol (EeCA) exposure.

Exhaled e-cigarette aerosol could also deposit to indoor surfaces, leading to “thirdhand” e-cigarette aerosol (THA) exposure. Similar to thirdhand smoke exposure, THA exposure includes not only contacting residual e-cigarette aerosols on indoor surfaces, but also pathways such as aerosolization and/or evaporation and conversion to secondary toxic chemicals.11 Recently, thirdhand smoke exposure has been highlighted as an emerging public health concern,12 due to the long residence time of nicotine (several months or years) as well as carcinogenic tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) converted from nicotine residues.11–13 Children are particularly vulnerable to THA or thirdhand smoke exposures because of their specific behaviors (eg, hand-to-mouth behaviors).14

Despite the potential importance of EeCA and THA exposures, the contribution of indoor e-cigarette use on THA exposure remains understudied8; and only a small number of studies reported increased levels of indoor airborne particles,15–20 nicotine,15,17,19,21–24 and other harmful chemicals15,17,22,25 after e-cigarette vaping, and the majority the indoor EeCA studies were conducted in controlled chambers.15–17,22,25–27 The aim of this study is to examine the impact of indoor e-cigarette use on EeCA and THA exposures. The study was conducted in five selected vape-shops in New Jersey, United States. Vape-shops often offer tasting samples to their patrons, and therefore provide “real-world” environments to study EeCA and THA exposures. We measured indoor air quality (ie, CO2, NO2, PM2.5, aldehydes, nicotine, and TSNAs) during opening and closing shop hours. We also measured nicotine and TSNA levels on the vape-shop indoor surfaces and on five different materials placed in the vape-shops.

Materials and Methods

Vape-Shops

A convenience sample of five vape-shops in New Jersey, United States was selected in this study between August 2016 and December 2017 (Supplementary Figure S1). During the recruitment visit, we checked indoor environment and air purifiers in the vape-shops. We confirmed that the vape-shops would be operating as usual during sampling and no additional ventilation would be added. The indoor volume of a vape-shop was measured using a laser distance measuring tool (Fluke, Everett, WA). A research staff member stayed in the vape-shops during opening hours of the sampling campaign to record the number of occupants and e-cigarette users in the vape-shops (5-minute intervals).

Indoor Air Quality Measurement

Indoor air quality in the five vape-shops was measured for 24 hours using a customized indoor sampling suitcase (Supplementary Figure S2). Indoor CO2, temperature, and relative humidity were measured using Extech CO210 (Extech Instruments, Waltham, MA). Particle size distributions were measured using a portable scanning mobility particle sizer (Kanomax PAMS, 10–436 nm, KANOMAX USA, New Jersey, NJ) and an optical particle counter (Kanomax 3886, 0.3–5.0 µm, KANOMAX USA, New Jersey, NJ) to cover a wide range of aerosol sizes. Particulate matter (PM2.5) mass concentrations were measured using a TSI SidePak AM510 (TSI Incorporated, Shoreview, MN). All particle measurement devices were factory calibrated. NO2 concentrations were measured using a Cairpol CairSens sensor (Cairpol Environment, POISSY Cedex, France). Air exchange rates (hour−1) for the vape-shops were calculated using the decreasing rate of the observed CO2 levels after vape-shops were closed at night. All real-time devices were operated 24 hours to cover opening and closing store hours.

Nicotine, TSNAs, and aldehydes (ie, formaldehyde and acetaldehyde) were measured separately during store opening and closing hours. Personal Modular Impactor for PM2.5 collection (SKC Inc, Eighty Four, PA) containing Teflon coated glass fiber filter (soaked with 0.1% ascorbic acid [≥99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO] and dried within a biosafety cabinet, Pall Corporation, Port Washington, NY) and 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) cartridge (Waters Sep-Pak DNPH-Silica cartridge, Waters, Milford, MA) were connected with a SKC 44XR pump (SKC Inc, Eighty Four, PA) to collect airborne nicotine and TSNAs, and aldehydes, respectively. A research staff member replaced the filter pad and the DNPH cartridge each day, right before a shop was closed to distinguish opening- and closing-hour concentrations. After sampling, quinoline (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was spiked as internal standard onto the glass fiber filter, which was transported to the laboratory and stored at −20°C until analysis. DNPH cartridges were stored at 4°C and analyzed within 24 hours using a method described below.

Vape-Shop Surface Sampling

Surface nicotine and TSNA samples were collected from four different places (eg, a show case, a television set, a picture frame, and floor) per vape-shop. A template of known area (1 ft × 1 ft, SKC Inc, Eighty Four, PA) was affixed to a surface, which was wiped using a KimWipe (Kimberly-Clark Professional, Roswell, GA) soaked with ethanol containing 0.1% ascorbic acid (≥99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The entire space within the template was wiped vertically first and then horizontally, and the procedure repeated twice. After sampling, quinoline was spiked as internal standard onto KimWipes, which were immediately placed into 15 mL amber vials with a Teflon cap and transported to the laboratory within an hour. Samples were stored at −20°C until analysis.

Nicotine deposition and TSNAs formation on different materials were also measured. Three materials, a piece of glass (5 in × 8 in, purchased from a local retailor), a piece of paper (5 in × 8 in, Whatman rectangular cellulose filter paper, GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA), and a piece of baby clothing material (5 in × 8 in, 100% cotton cloth purchased from a local retailor, hand washed with ultrapure water then dried in a biosafety cabinet before sampling), were placed in separate frames (5 in × 8 in, purchased from a local retailer). In addition, a rubber ball (5 cm in diameter) and a fur ball (polyester) were also purchased from a baby toys retailer. The five materials were left in each vape-shop for 14 days on a shelf near a main countertop where e-cigarette users were frequently seen vaping (Supplementary Figure S3). After collecting sample materials, the glass and the rubber ball were wiped using KimWipes soaked with ethanol with 0.1% ascorbic acid, then the Kimwipe were stored in 15 mL amber vials. The paper, cloth, and fur ball were torn to pieces and stored in 120 mL amber jars. All samples were spiked with quinoline as internal standard and stored at −20°C until analysis.

Aldehyde Analysis

The sampled DNPH cartridges were eluted with 4 mL of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade acetonitrile (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 20 µL of the eluted DNPH-aldehyde derivatives were injected into a HPLC/UV system (a Perkin Elmer Series 200 HPLC and a Perkin Elmer 785a UV/vis detector, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) which was equipped with a Nova-Pak C18 column (Waters, Milford, MA). A combination of two mobile phases (Solvent A and Solvent B) were used as described in Supplementary Table S1: Solvent A was comprised of H2O (HPLC grade, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), tetrahydrofuran (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH), and acetonitrile (6:1:3 [vol/vol]); and Solvent B was comprised of acetonitrile and H2O (6:4 [vol/vol]). The flow rate of the mobile phase was set constant at 1 mL/min and the UV detector was set at an absorbance wavelength of 365 nm. External calibration curves for formaldehyde and acetaldehyde were prepared using purchased DNPH-aldehyde analytical standards (ResTek, Bellefonte, PA). Limits of detection were 0.23 and 0.17 µg/mL for formaldehyde and acetaldehyde, respectively.

Nicotine and TSNA Analysis

Nicotine from the glass fiber filters, the surface wipes, and the deposition sample materials were extracted using methanol (HPLC grade, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, NH). Sample extracts (1 µL) were injected into an ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC)–tandem mass spectrometer (MS/MS) (Waters Quattro micro UPLC/MS/MS system, Waters, Milford, MA) equipped with a Waters BEH C18 column (1.7 µm, 2.1 × 50 mm, Waters, Milford, MA). The mobile phase conditions are described in Supplementary Table S2. Nicotine and quinoline were identified using parent/daughter mass to charge ratios of 163/132 and 130/77, respectively. A six-point external calibration curve was established using a diluted nicotine solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in methanol. The limits of detection for nicotine was 7.7 ng/mL.

Nitrosation of nicotine forms carcinogenic TSNAs.13 We measured two TSNAs, 4-(N-methyl-N-nitrosamino)-4-(3-pyridyl)butanal (NNA) and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK), in all glass fiber filters, surface wipes, and the five different materials placed in the vape-shops. After adding 5 ng of deuterated NNA and NNK as internal standards (Toronto Research Chemical, ON, Canada), the extracts were concentrated under a pure nitrogen stream, and the concentrated samples were reconstituted to 100 µL using methanol, then 5 µL aliquots were injected into the UPLC/MS/MS (chromatographic parameters are described in Supplementary Table S3). Calibrations were performed with NNA, NNA-d3, NNK, and NNK-d4 solutions in methanol (Toronto Research Chemical, ON, Canada) under m/z pairs (parent/daughter) of 207/120, 210/123, 208/122, and 212/126, respectively. The limits of detection for NNA was 1.0 and 0.9 ng/mL for NNK.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report indoor contaminant concentrations. Two-tailed Student’s t tests or Mann–Whitney U tests were conducted to examine the diurnal impacts of vape-shop occupancy on indoor contaminant levels. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the associations between measured contaminant concentrations and environmental determinants. Statistical significances were determined at α = 0.05 and all statistical analyses were conducted using R 3.6.1 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Table 1 shows sampling dates, open hours, store volumes, air exchange rates, the number of occupants, and e-cigarette users, and the observed indoor air quality for the studied vape-shops. All the vape-shops had mechanical ventilation with air exchange rates ranging from 0.126/hour to 0.152/hour. Vape-shop #3 was the most visited vape-shop (e-cigarette users plus nonusers). E-cigarette users were present the most in vape-shop #1. Temperature and relative humidity in the vape-shops were in the range of 21–23°C and 49%–53% relative humidity for opening hours, and 19–27°C and 43%–59% relative humidity for closing hours.

Table 1.

Ventilation Rates (Air Change per Hour, ACH), Number of Occupants (Median [Interquartile Range, IQR]), Active E-cigarette Vapers (Median [IQR]), and Indoor Air Qualitiesa (Time-Weighted Average [TWA] ± Weighted Standard Deviation) for the Studied Vape-Shopsb

| Occupant (person) | Active vaper (person) | CO2 (ppm) | NO2 (ppb) | PM2.5 (mg/m3) | CMD (nm) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vape-shop ID | Date | Open hours | Volume (m3) | ACH (h−1) | Median (IQR) | Total | Median (IQR) | Total | Open | Close | Open | Close | Open | Close | Open | Close |

| 1 | 8/25/16 | 12 pm to 10 pm | 118.7 | 0.146 | 4 (2) | 32 | 2 (2) | 24 | 663 ± 157 | 488 ± 164 | 16.6 ± 6.7 | 6.9 ± 9.7 | 3.49 ± 2.64 | 0.19 ± 3.27 | 286 ± 54 | 174 ± 106 |

| 2 | 9/23/16 | 10 am to 10 pm | 185.4 | 0.126 | 4 (2) | 42 | 2 (1) | 21 | 964 ± 226 | 696 ± 219 | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 1.19 ± 1.58 | 0.12 ± 1.52 | 240 ± 58 | 185 ± 58 |

| 3 | 10/3/17 | 10 am to 10 pm | 471.4 | 0.152 | 5 (3) | 43 | 1 (1) | 13 | 550 ± 27 | 472 ± 78 | 15.5 ± 7.0 | 6.7 ± 9.1 | 1.09 ± 1.74 | 0.02 ± 1.07 | 230 ± 37 | 174 ± 55 |

| 4 | 11/22/17 | 11 am to 8 pm | 138.1 | 0.135 | 4 (2) | 27 | 1 (1) | 17 | 991 ± 109 | 586 ± 413 | 3.8 ± 1.7 | 3.9 ± 1.6 | 2.51 ± 2.10 | 0.05 ± 2.47 | 255 ± 38 | 173 ± 85 |

| 5 | 12/5/17 | 11 am to 8 pm | 163.1 | 0.151 | 2 (1) | 14 | 1 (0) | 12 | 591 ± 38 | 506 ± 28 | 11.7 ± 3.2 | 8.3 ± 2.0 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 180 ± 11 | 174 ± 6 |

| All | 752 ± 134 | 550 ± 225 | 10.2 ± 4.7 | 5.4 ± 6.1 | 1.66 ± 1.84 | 0.08 ± 2.01 | 238 ± 43 | 176 ± 70 | ||||||||

aCarbon dioxide (CO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), particulate matter (PM2.5), and median particle size (count median diameter, CMD) for opening and closing hours.

bOther indoor air contaminants (ie, aldehydes and nicotine) are shown in Figure 1.

CO2 concentrations in all vape-shops were significantly higher during opening hours than closing hours (p < .001) due to the exhaled breath from the occupants (Table 1). The vape-shop indoor CO2 concentrations peaked during opening hours, and it rapidly decreased during closing hours as shown in Supplementary Figure S4. Indoor CO2 levels were significantly correlated with the number of occupants in the vape-shops (ρ = 0.575–0.926, p < .001). Vape-shops #2 and #4, with slightly lower air exchange rates, showed significantly higher CO2 concentrations than the other vape-shops (p < .001).

Vape-shop indoor NO2 concentrations also depended on air exchange rates. No indoor NO2 sources were observed in any vape-shops in this study; and outdoor NO2, primarily generated from traffic emissions, was brought into the indoor environments through air exchange. Vape-shops with higher air exchange rates (#1, #3, and #5) showed significantly higher NO2 concentrations than the other vape-shops (#2 and #4) (p < .001). In addition, all vape-shops, except for vape-shop #4, showed significantly higher NO2 concentrations during opening hours than the concentrations during closing hours (p < .001).

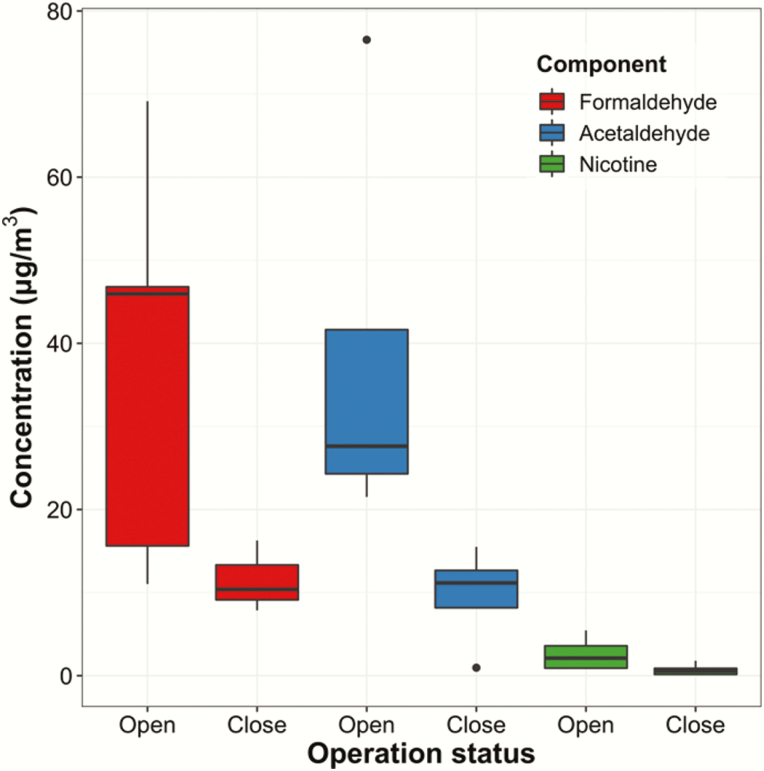

Indoor air contaminants from exhaled e-cigarette aerosols were at much higher level during shop opening hours than the level during shop closing hours (p < .001, Table 1 and Figure 1), causing substantial EeCA exposure. PM2.5 concentrations and particle sizes (count median diameter) depended on the number of e-cigarette users present in vape-shops (Supplementary Figure S4 and Supplementary Table S4) (ρ = 0.366–0.761 and p < .001 for PM2.5, and ρ = 0.543–0.844 and p < .001 for count median diameter). Vape-shops #1 and #4 showed higher PM2.5 concentrations than the other vape-shops, although the differences were not statistically significant, presumably due to the small sample size. Indoor e-cigarette use increased not only PM2.5 concentrations but also the level of other harmful chemicals in the indoor environment. Airborne formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and nicotine concentrations during shop opening hours were 3–4 times higher than the chemical concentrations measured during shop closing hours (Figure 1). Airborne aldehyde and nicotine concentrations were moderately associated with the total number of active vapers, although the associations were not statistically significant due to small sample sizes (ρ = 0.734, p = .233 for formaldehyde; ρ = 0.612, p < .350 for acetaldehyde; and ρ = 0.447, p = .450 for nicotine).

Figure 1.

Indoor airborne formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and nicotine concentrations measured in the vape-shops during opening and closing hours. Tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) were nondetected in air samples.

The presence of nicotine and TSNAs on various indoor surfaces strongly indicates that e-cigarette vaping potentially causes THA exposure (Table 2). Vape-shop #3 showed the highest surface nicotine (730.0 ± 1000.0 µg/m2) and NNK (174.1 ± 224.0 µg/m2) levels among the studied vape-shops. Ranges of surface nicotine and TSNAs levels were 0.84–2182 µg/m2 for nicotine, nondetect–23.8 ng/m2 for NNA, and nondetect–430 ng/m2 for NNK across the vape-shops. The observed surface nicotine concentrations were correlated with the median number of active vapors present in a vape-shop per hour (ρ = 0.671, p = .215), and correlated with airborne nicotine concentrations (ρ = 0.900, p = .335), although the correlations are not statistically significant due to the small sample size. Substantial amounts of nicotine deposited on the materials placed within the vape-shops during the 14-day sampling period (Table 2). The highest amount of nicotine and TSNAs were observed on paper (1097.2 ± 580.6 µg/m2 for nicotine, 199.9 ± 195 ng/m2 for NNA, and 102.3 ± 69.4 ng/m2 for NNK), followed by the baby clothing material (814.7 ± 732.7 µg/m2 for nicotine, 57.8 ± 6.30 ng/m2 for NNA, and 75.6 ng/m2 for NNK) and glass (325.4 ± 547.8 µg/m2 for nicotine, 25.0 ng/m2 for NNA, and 11.4 ng/m2 for NNK). Ranges of nicotine concentrations observed on the rubber ball surface and the fur ball hair were nondetect–31.0 µg/m2 and 13.5–31.0 ng/g hair, respectively, across the vape-shops, while NNA and NNK were not detected. The apparent nicotine deposition and/or adsorption rates, which is the observed surface nicotine concentration divided by sampling duration (14 days), were 78.4 ± 41.5, 58.2 ± 52.3, and 18.6 ± 35.5 µg/m2/day (mean ± SD) for paper, baby clothing material, and glass, respectively. The deposited nicotine concentrations on glass, paper, clothing, and fur ball surfaces were strongly correlated with the median number of active vapers present in a vape-shop per hour (ρ = 0.894–0.949, p = .040–.051). NNK levels on the material surfaces were significantly associated with surface nicotine levels (ρ = 0.645, p = .037), while NNA showed week correlation (ρ = 0.259, p = .417).

Table 2.

Nicotine, NNA, and NNK Levels in Surface Wipe Samples (n = 4 for Each Vape-Shop) and on Different Materials (Glass, Paper, Clothing, Rubber Ball, and Fur Ball) Left for 14 Days at the Vape-Shops

| Surface wipea | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Vape-shop ID | Mean ± SD | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | Glass | Paper | Clothing | Rubber ball | Fur ballb |

| Nicotine (µg/m2) | 1 | 189.8 ± 283.0 | 612.3 | 58.4 | 76.3 | 12.1 | 108.2 | 1215 | 523.3 | 15.7 | — c |

| 2 | 5.70 ± 1.40 | 7.30 | 6.41 | 4.29 | 4.80 | NDd | 1396 | 726.8 | ND | 17.2 | |

| 3 | 730.0 ± 1000.0 | 2181.8 | 65.0 | 601.6 | 71.7 | 1145 | 1554 | 2073 | 12.9 | 67.7 | |

| 4 | 134.2 ± 227.1 | 28.1 | 474.7 | 14.6 | 19.3 | 28.2 | 1233 | 581.7 | 31.0 | 31.0 | |

| 5 | 58.1 ± 54.6 | 119.4 | 25.4 | 0.84 | 86.9 | 20.2 | 88.2 | 168.9 | 16.5 | 13.5 | |

| NNA (ng/m2) | 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 474.4 | 52.2 | ND | — |

| 2 | 12.2 ± 16.4 | 0.65 | <LODe | ND | 23.8 | 25.0 | 171.7 | 56.5 | <LOD | ND | |

| 3 | 27.38 | 27.4 | ND | ND | ND | <LOD | 15.3 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | <LOD | 64.6 | ND | <LOD | |

| 5 | 9.09 | ND | ND | ND | 9.09 | ND | 138.0 | <LOD | ND | ND | |

| NNK (ng/m2) | 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | <LOD | 131.8 | ND | ND | — |

| 2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | <LOD | ND | 65.1 | ND | <LOD | ND | |

| 3 | 174.1 ± 224.0 | 78.8 | 13.5 | 430.0 | ND | ND | 28.1 | 75.6 | ND | <LOD | |

| 4 | 4.22 | 4.22 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 184.0 | <LOD | ND | ND | |

| 5 | 10.6 | ND | ND | 10.6 | ND | 11.4 | <LOD | ND | ND | ND | |

NNA = 4-(N-methyl-N-nitrosamino)-4-(3-pyridyl)butanal; NNK = 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone.

aSurface samples (n = 4, sample IDs S1–4 from the table): showcase (S1–2), window (S3), and wall (S4) for vape-shop 1; showcase (S1–4) for vape-shop 2; showcase (S1–2), shelve (S3), and wall (S4) for vape-shop 3; showcase (S1), shelve (S2), window (S3), and frame (S4) for vape-shop 4; and showcase (S1–2), window (S3), and wall (S4) for vape-shop 5.

bUnits for nicotine and TSNAs were ng/g hair and pg/g hair, respectively.

cSampling was not completed.

dND indicates nondetected.

eBelow limit of detection (<LOD) indicates observed values were less than method detection limits.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study aimed to measure EeCA and THA chemical components in vape-shops. Although the study was conducted in vape-shops, our results strongly suggest that e-cigarette vaping causes passive e-cigarette aerosol exposures in indoor environments, including both secondhand and THA exposures.

Indoor Environmental Quality of the Vape-Shops

The observed air exchange rates of the studied vape-shops were much lower than the reported average air exchange rate in US retail stores (1.0/hour ± 0.7/hour).28 Our observed air exchange rates in vape-shops varied by the type, location, and strength of the ventilation system. Indeed, vape-shops #1, #2, and #3 actively used an air purifier and a ceiling fan, whereas vape-shop #4 only had an exhaust ventilation fan on top of the front door, which was occasionally used when the air became hazy, and staff at vape-shop #5 occasionally opened the front door for ventilation. Improved ventilation should be required in vape-shops because indoor air quality depends on ventilation capacity.29 In addition, ventilation systems in the vape-shops should be isolated or equipped with filtration systems to prevent the spread of nicotine and other harmful chemicals to nearby stores.23

The observed indoor CO2 concentrations depended on the number of occupants and air exchange rates. Although no vape-shops exceeded indoor CO2 limit value (ie, 1250 ppm, assuming outdoor CO2 level is 550 ppm) recommended by ASHRAE (The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers),29 vape-shops #2 and #4 showed elevated levels of CO2 (>950 ppm), presumably due to high occupancy and/or low ventilation. In contrast, higher ventilation rates resulted in the higher indoor NO2 concentrations (vape-shops #1, #3, and #5 vs. vape-shops #2 and #4). Higher ventilation rates favored the penetration of outdoor traffic-generated NO2 into the vape-shops. The penetrated NO2 is a precursor of nitrous acid (HONO),30 which is a source of reactive hydroxyl radical and could convert nicotine to carcinogenic TSNAs on surfaces.13 Therefore, ventilation systems in vape-shops should not introduce outdoor NOx in order to reduce the risk of exposure to TSNAs.

Secondhand E-cigarette Aerosols

The increased levels of indoor PM2.5 and airborne toxic chemicals demonstrate that e-cigarette vaping causes passive exposure, especially in indoor environments. Although PM2.5 levels in all studied vape-shops did not exceed the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) permissible exposure limit (PEL) value of 5 mg/m3 (8 hours time-weighted average, respirable particles),31 the observed PM2.5 levels in vape-shops were much higher than the reported PM2.5 concentrations in retail stores and other indoor environments (eg, 11.6 µg/m3 in retail sites and 31.6 µg/m3 for groceries).32 During monitoring, our research staff anecdotally noted that staff and customers at vape-shops #1 and #4 predominantly used “mod” vaping devices, which consist of sub-ohm coils and high-voltage battery packs facilitating production of large quantities of e-cigarette aerosols. Indoor use of “mod” devices at vape-shops #1 and #4 could explain the substantially higher PM2.5 concentrations in these two shops than PM2.5 levels in the other shops. The observed large particle sizes (count median diameters) at vape-shops #1 and #4 could also be attributed to the use of “mod” devices, which are known to generate larger particles than other types of e-cigarettes with lower power output.33

It should be noted that optical particle measurement devices (ie, KANOMAX 3886 and TSI SidePak) employed in our study were factory calibrated using solid particles (ie, polystyrene latex particle and Arizona dust, respectively) that have different optical and physical properties from liquid e-cigarette aerosols. The property differences between solid and liquid particles might decrease measurement accuracy. However, a previous study demonstrated that e-cigarette particle mass concentration measured by factory calibrated TSI SidePak had strong agreement with gravimetric method (less than 1% difference).19

Generally, airborne aldehydes and nicotine levels were higher during vape-shop opening hours than the concentrations during closing hours. Indoor aldehydes and nicotine levels during shop opening hours were lower than exposure limits (OSHA PEL) of 0.92, 360, and 0.5 mg/m3 for formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and nicotine, respectively.31 However, many vape-shop staff would be at higher risks of total exposure since most staff were e-cigarette users themselves (ie, primary exposure).

Thirdhand E-cigarette Aerosols

The presence of nicotine and carcinogenic TSNAs on indoor surfaces provides clear evidence that indoor e-cigarette vaping leads to THA exposure. We observed surface nicotine in all studied vape-shops. Vape-shop #3, which had a “e-juice bar” (ie, an area where customers could try e-liquids before purchasing them), had the highest surface nicotine levels (71.7–2181.8 µg/m2). High surface nicotine levels in vape-shop #3 could be attributable to aerosol deposition during e-liquid tasting or spilled e-liquids at the “juice bar.” Surface nicotine level depends on a variety of factors, including the number of vapers, vaping or smoking frequency, nicotine content of the devices being used, surface materials, indoor volume and ventilation (ie, air change rate), and cleaning practices. Extended monitoring in different indoor environments is needed to better understand the impact of indoor e-cigarette use on thirdhand nicotine exposure.

E-cigarette use could also increase the exposure to TSNAs. Nicotine deposited to surfaces can react with nitrous acid to form NNA and NNK.13 Since the levels of TSNAs in the air were not detectable, the presence of carcinogenic NNA and NNK on surfaces indicates that deposited nicotine is the precursor of NNA and NNK on surfaces. As stated above, NO2 is a source of indoor nitrous acid, and therefore, indoor e-cigarette use could lead to higher risks of exposure to TSNAs for homes with indoor combustion sources (eg, natural gas heating or cooking) or closer to highways.

E-cigarettes Versus Conventional Cigarettes

In this study, e-cigarettes induced lower levels of indoor air nicotine than cigarette smoking (Table 3). Indoor air nicotine concentrations reported in prior studies ranged from 3 to 22 µg/m,3,34 which are higher than the airborne nicotine levels observed in this study. Previous studies also reported that airborne nicotine levels at e-cigarette user’s homes (0.06–0.32 µg/m3) were lower than that at active smokers’ homes (0.21–1.99 µg/m3).21 In addition, studies conducted with controlled exposure chambers also demonstrated that e-cigarettes released less nicotine and other toxic chemicals than conventional cigarettes.15,25,26,42

Table 3.

Indoor Air and Surface Nicotine and TSNAs Concentrations Associated With E-cigarette Vaping or Cigarette Smoking

| E-cigarette | Cigarette | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Air | Nicotine (µg/m3) | 0.9–5.1 | 3–22a |

| 0.06–0.32b | 0.21–1.99b | ||

| 0.5–13c | |||

| NNA (ng/m3) | NDd | — | |

| NNK (ng/m3) | ND | ND–13.5e | |

| ND–29f | |||

| Surface | Nicotine (µg/m2) | 0.84–2182 | 5.1–77g |

| 7.7h | 1303h | ||

| 33–8520c | |||

| NNA (ng/m2) | ND–474 | 3–256i | |

| NNK (ng/m2) | ND–430 | 0.4–36.5i | |

| 8.4–19.9j |

Values for e-cigarettes were observed in our study unless otherwise indicated, and values for cigarette smoking were obtained from previous studies. TSNAs = tobacco specific nitrosamines; NNA = 4-(N-methyl-N-nitrosamino)-4-(3-pyridyl)butanal; NNK = 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone.

aObserved airborne nicotine levels in indoor environments where smoking was allowed.34

bObserved indoor air nicotine levels measured at e-cigarette or cigarette users’ homes.21

cObserved airborne and surface nicotine levels in casino.35

dND indicates nondetected.

eAirborne NNK concentrations observed in office spaces with poor ventilation.36

fAirborne NNK concentrations observed in bars, restaurants, and train.37

gObserved surface nicotine and NNK levels in homes, cars, and hotel rooms with active smoking.38–40

hMean surface nicotine levels observed at e-cigarette or cigarette users’ homes.41

iEstimated surface NNA and NNK concentrations.13

jObserved NNK concentration in smokers’ homes.40

However, thirdhand exposure to nicotine and carcinogenic TSNAs could be much higher in vape-shops than that caused by cigarette smoking (Table 3). Surface nicotine levels in vape-shops could even exceed nicotine levels observed in cigarette smokers’ homes and cars. Surface nicotine levels in smoker’s homes and cars commonly range from 5.1 to 77 µg/m2,38–40 while a recent study reported a much higher surface nicotine level of 1303 µg/m2 at cigarette smokers’ home.41 The surface nicotine concentrations observed in this study were comparable or higher than the reported surface nicotine levels induced by active smoking38–41 though lower than those on casino surfaces.35 Observed vape-shop surface TSNAs showed higher ranges comparing to the levels observed at homes (84–19.9 ng NNK/m2)40 and estimated based on the empirical models (3–256 ng NNA/m2 and 0.4–36.5 ng NNK/m2).13 NNK is known to cause cancer and other adverse health effects including metabolic changes, mutation, DNA damage, and oxidative stress.43 NNA has also demonstrated genotoxicity similar to NNK at nanomolar level exposures.44 The NNA and NNK levels observed in this study are of particular concern as they are higher than levels observed in active smoker’s homes40 or those estimated based on empirical relationships13 (Table 3).

Policy Implications and Future Research

Although this study was limited by the small sample size (1-day sampling in five vape-shops in NJ), which generated large variation in observations, results from the study provide novel data and key public health insights into EeCA and THA exposures.

As of October 2019, 21 states including New Jersey, where we conducted our study, completely banned indoor e-cigarette vaping in smoke-free public places; however, some state (ie, DE, NY, RI, and VT) grant exceptions to retail e-cigarette stores.45 Our findings can inform OSHA, state authorities, and other occupational or government agencies regarding indoor air policies related to e-cigarette use, particularly in vape-shops. Specifically, there is an urgent need to ensure that vape-shops maintain suitable ventilation systems and cleaning practices to protect customers, employees, and bystanders. Indeed, inadequate ventilation systems have been shown to increase indoor nicotine levels in a vape-shop and adjacent businesses.23

Furthermore, it has been reported that e-cigarette-only users and dual users (ie, e-cigarettes and cigarettes) are less likely to have strictly enforced vape-free indoor policies in their homes and cars compared with exclusive cigarette smokers.46 Since our study was not conducted in residential homes but in vape-shops, contaminant levels observed in this study might not be directly applicable to EeCA and THA exposures in other microenvironments. However, this study does provide convincing evidence that nicotine can deposit/be adsorbed on different surfaces commonly seen in residential homes, and that TSNAs can form and retain on those surfaces. The physicochemical mechanisms underlining TSNAs formation are generic, regardless of microenvironments. That said, it is plausible that THA exposures in homes and cars could be compatible to or even higher than in vape-shops because residential homes and cars have larger surface areas made of materials (ie, paper, fabric, and floor tile, etc.) that attract more nicotine, as demonstrated in this study, compared with glass surfaces which are abundant in vape-shops (Table 2). Moreover, higher nicotine-to-TSNAs conversion might occur in cars or residential homes than in vape-shops, especially for homes being close to highways or having combustion sources.47

Children’s exposure to EeCA and THA at home is of a particular concern. At homes and in cars, children are more likely to be exposed to EeCA and THA than secondhand and thirdhand cigarette smoke.46 Recent studies highlighted that dermal uptake is a major exposure route for nicotine, which makes children even more vulnerable to EeCA and THA exposure. Conventionally, inhalation of indoor air, surface dermal contact, and ingestion (hand-to-mouth behavior) were considered as the primary exposure routes through which individuals can take up nicotine and other toxicants from indoor air and surfaces.11,14,48 However, recent reports have shown that direct dermal uptake of nicotine from air can exceed inhaled nicotine dose.49 Bekö et al. reported that wearing nicotine contaminated clothes could result in an over 17-fold higher nicotine exposure than wearing uncontaminated clothes.50 In addition, children’s dermal exposure to nicotine is more likely to be associated with poisoning symptoms than accidental nicotine ingestion.51 Our study does demonstrate that nicotine can deposit/be adsorbed on baby’s clothes and toys, and that TSNAs can form and retain on baby’s clothes. Prenatal and early childhood nicotine exposures have been found to increase nicotine dependency in later life stages.52

This study adds new evidence and policy implications in the field of EeCA and THA. To better inform public health initiatives and better estimate the impact of e-cigarette use on individual health outcomes, further long-term studies in various microenvironments are needed to understand secondhand and thirdhand exposures to e-cigarette aerosols in different indoor settings.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Supplementary data are available at Nicotine & Tobacco Research online.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all vape-shop owners for their support of the study. The authors would like to thank Dr Lara Gundel at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory for the valuable discussion, and Dr Clifford Weisel at Rutgers University for aldehyde analysis.

Funding

This study was supported by the Cancer Institute of New Jersey, the New Jersey Health Foundation, and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P30 ES005022). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Geiss O, Bianchi I, Barrero-Moreno J. Correlation of volatile carbonyl yields emitted by e-cigarettes with the temperature of the heating coil and the perceived sensorial quality of the generated vapours. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2016;219(3):268–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gillman IG, Kistler KA, Stewart EW, Paolantonio AR. Effect of variable power levels on the yield of total aerosol mass and formation of aldehydes in e-cigarette aerosols. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2016;75:58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khlystov A, Samburova V. Flavoring compounds dominate toxic aldehyde production during e-cigarette vaping. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50(23):13080–13085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kosmider L, Spindle TR, Gawron M, Sobczak A, Goniewicz ML. Nicotine emissions from electronic cigarettes: individual and interactive effects of propylene glycol to vegetable glycerin composition and device power output. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;115:302–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pankow JF, Kim K, McWhirter KJ, et al. Benzene formation in electronic cigarettes. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Talih S, Balhas Z, Eissenberg T, et al. Effects of user puff topography, device voltage, and liquid nicotine concentration on electronic cigarette nicotine yield: measurements and model predictions. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):150–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Uchiyama S, Senoo Y, Hayashida H, Inaba Y, Nakagome H, Kunugita N. Determination of chemical compounds generated from second-generation e-cigarettes using a sorbent cartridge followed by a two-step elution method. Anal Sci. 2016;32(5):549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. US EPA. Respiratory Health Effects of Passive Smoking: Lung Cancer and Other Disorders. Vol EPA/600/6-90/006F. Washington, DC: Office of Research and Development, Office of Air and Radiation, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization. Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems and Electronic Non-Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS/ENNDS), FCTC/COP/7/11. Delhi, India: WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burton A. Does the smoke ever really clear? Thirdhand smoke exposure raises new concerns. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(2):A70–A74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matt GE, Quintana PJ, Destaillats H, et al. Thirdhand tobacco smoke: emerging evidence and arguments for a multidisciplinary research agenda. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(9):1218–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sleiman M, Gundel LA, Pankow JF, Jacob P 3rd, Singer BC, Destaillats H. Formation of carcinogens indoors by surface-mediated reactions of nicotine with nitrous acid, leading to potential thirdhand smoke hazards. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(15):6576–6581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferrante G, Simoni M, Cibella F, et al. Third-hand smoke exposure and health hazards in children. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2013;79(1):38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Czogala J, Goniewicz ML, Fidelus B, Zielinska-Danch W, Travers MJ, Sobczak A. Secondhand exposure to vapors from electronic cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(6):655–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Protano C, Manigrasso M, Avino P, Sernia S, Vitali M. Second-hand smoke exposure generated by new electronic devices (IQOS® and e-cigs) and traditional cigarettes: submicron particle behaviour in human respiratory system. Ann Ig. 2016;28(2):109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schober W, Szendrei K, Matzen W, et al. Use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) impairs indoor air quality and increases FeNO levels of e-cigarette consumers. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2014;217(6):628–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fernández E, Ballbè M, Sureda X, Fu M, Saltó E, Martínez-Sánchez JM. Particulate matter from electronic cigarettes and conventional cigarettes: a systematic review and observational study. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2015;2(4):423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen R, Aherrera A, Isichei C, et al. Assessment of indoor air quality at an electronic cigarette (Vaping) convention. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2018;28:522–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Soule EK, Maloney SF, Spindle TR, Rudy AK, Hiler MM, Cobb CO. Electronic cigarette use and indoor air quality in a natural setting. Tob Control. 2017;26(1):109–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ballbè M, Martínez-Sánchez JM, Sureda X, et al. Cigarettes vs. e-cigarettes: passive exposure at home measured by means of airborne marker and biomarkers. Environ Res. 2014;135:76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu J, Liang Q, Oldham M, et al. Determination of selected chemical levels in room air and on surfaces after the use of cartridge-and tank-based e-vapor products or conventional cigarettes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(9):969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Khachatoorian C, Jacob Iii P, Benowitz NL, Talbot P. Electronic cigarette chemicals transfer from a vape shop to a nearby business in a multiple-tenant retail building. Tob Control. 2019;28(5):519–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khachatoorian C, Jacob P 3rd, Sen A, Zhu Y, Benowitz NL, Talbot P. Identification and quantification of electronic cigarette exhaled aerosol residue chemicals in field sites. Environ Res. 2019;170:351–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schripp T, Markewitz D, Uhde E, Salthammer T. Does e-cigarette consumption cause passive vaping? Indoor Air. 2013;23(1):25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Flouris AD, Chorti MS, Poulianiti KP, et al. Acute impact of active and passive electronic cigarette smoking on serum cotinine and lung function. Inhal Toxicol. 2013;25(2):91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Melstrom P, Koszowski B, Thanner MH, et al. Measuring PM2.5, ultrafine particles, nicotine air and wipe samples following the use of electronic cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(9):1055–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zaatari M, Nirlo E, Jareemit D, Crain N, Srebric J, Siegel J. Ventilation and indoor air quality in retail stores: a critical review (RP-1596). HVAC&R Res. 2014;20(2):276–294. [Google Scholar]

- 29. ASHRAE. Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality, ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 62.1. Atlanta, GA: American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gligorovski S. Nitrous acid (HONO): an emerging indoor pollutant. J Photochem Photobiol A: Chem. 2016;314:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 31. NIOSH. NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. U.S. Cincinnati, Ohio: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bennett DH, Fisk W, Apte MG, et al. Ventilation, temperature, and HVAC characteristics in small and medium commercial buildings in California. Indoor Air. 2012;22(4):309–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Floyd EL, Queimado L, Wang J, Regens JL, Johnson DL. Electronic cigarette power affects count concentration and particle size distribution of vaping aerosol. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0210147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hammond SK. Exposure of US workers to environmental tobacco smoke. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107(suppl 2):329–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matt GE, Quintana PJE, Hoh E, et al. A Casino goes smoke free: a longitudinal study of secondhand and thirdhand smoke pollution and exposure. Tob Control. 2018;27(6):643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Klus H, Begutter H, Scherer G, Tricker AR, Adlkofer F. Tobacco-specific and volatile N-nitrosamines in environmental tobacco smoke of offices. Indoor Environment. 1992;1(6):348–350. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brunnemann KD, Cox JE, Hoffmann D. Analysis of tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines in indoor air. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13(12):2415–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Matt GE, Quintana PJ, Hovell MF, et al. Households contaminated by environmental tobacco smoke: sources of infant exposures. Tob Control. 2004;13(1):29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Matt GE, Quintana PJ, Fortmann AL, et al. Thirdhand smoke and exposure in California hotels: non-smoking rooms fail to protect non-smoking hotel guests from tobacco smoke exposure. Tob Control. 2014;23(3):264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Matt GE, Quintana PJE, Zakarian JM, et al. When smokers quit: exposure to nicotine and carcinogens persists from thirdhand smoke pollution. Tob Control. 2016;26(5):548–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bush D, Goniewicz ML. A pilot study on nicotine residues in houses of electronic cigarette users, tobacco smokers, and non-users of nicotine-containing products. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(6):609–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McAuley TR, Hopke PK, Zhao J, Babaian S. Comparison of the effects of e-cigarette vapor and cigarette smoke on indoor air quality. Inhal Toxicol. 2012;24(12):850–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hecht SS. Biochemistry, biology, and carcinogenicity of tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11(6):559–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hang B, Sarker AH, Havel C, et al. Thirdhand smoke causes DNA damage in human cells. Mutagenesis. 2013;28(4):381–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. ANRF. States and Municipalities with Laws Regulating Use of Electronic Cigarettes, as of October 1, 2019. Berkely, CA: American Nonsmoker’s Rights Foundation; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Drehmer JE, Nabi-Burza E, Walters BH, et al. Parental smoking and E-cigarette use in homes and cars. Pediatrics. 2019;143(4):e20183249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Alberts WM. Indoor air pollution: NO, NO2, CO, and CO2. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1994;94(2 Pt 2):289–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Asomaning K, Miller DP, Liu G, et al. Second hand smoke, age of exposure and lung cancer risk. Lung Cancer. 2008;61(1):13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bekö G, Morrison G, Weschler CJ, et al. Measurements of dermal uptake of nicotine directly from air and clothing. Indoor Air. 2017;27(2):427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bekö G, Morrison G, Weschler CJ, et al. Dermal uptake of nicotine from air and clothing: experimental verification. Indoor Air. 2018;28(2):247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Woolf A, Burkhart K, Caraccio T, Litovitz T. Childhood poisoning involving transdermal nicotine patches. Pediatrics. 1997;99(5):E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bélanger M, O’Loughlin J, Okoli CT, et al. Nicotine dependence symptoms among young never-smokers exposed to secondhand tobacco smoke. Addict Behav. 2008;33(12):1557–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.