Abstract

Background

Current evidence supports the involvement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val66Met polymorphism, and the ε4 allele of APOE gene in hippocampal-dependent functions. Previous studies on the association of Val66Met with whole hippocampal volume included patients of a variety of disorders. However, it remains to be elucidated whether there is an impact of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on the volumes of the hippocampal subfield volumes (HSv) in cognitively unimpaired (CU) individuals, and the interactive effect with the APOE-ε4 status.

Methods

BDNF Val66Met and APOE genotypes were determined in a sample of 430 CU late/middle-aged participants from the ALFA study (ALzheimer and FAmilies). Participants underwent a brain 3D-T1-weighted MRI scan, and volumes of the HSv were determined using Freesurfer (v6.0). The effects of the BDNF Val66Met genotype on the HSv were assessed using general linear models corrected by age, gender, education, number of APOE-ε4 alleles and total intracranial volume. We also investigated whether the association between APOE-ε4 allele and HSv were modified by BDNF Val66Met genotypes.

Results

BDNF Val66Met carriers showed larger bilateral volumes of the subiculum subfield. In addition, HSv reductions associated with APOE-ε4 allele were significantly moderated by BDNF Val66Met status. BDNF Met carriers who were also APOE-ε4 homozygous showed patterns of higher HSv than BDNF Val carriers.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to show that carrying the BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms partially compensates the decreased on HSv associated with APOE-ε4 in middle-age cognitively unimpaired individuals.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00429-020-02125-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: APOE-ε4, BDNF, Hippocampal subfields, Imaging genetics, Subiculum, Val66Met

Introduction

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a neurotrophin involved in neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity in the central nervous system, especially in the hippocampus, and has been implicated in the pathophysiology of several neuropsychiatric disorders (Bathina and Das 2015; Autry and Monteggia 2012; Numakawa et al. 2018). The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs6265 (also known as Val66Met), causes a valine (Val) to methionine (Met) substitution at codon 66 of BDNF protein. Particularly, the study of Val66Met polymorphism within the BDNF gene is of special interest because of its documented impact on hippocampal-dependent functions (Notaras and van den Buuse 2018; Toh et al. 2018; Egan et al. 2003; Hariri et al. 2003). Hence, extensive research focuses on the discovery of associations between BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and several hippocampal phenotypes. However, recent meta-analyses addressing hippocampal volumes for BDNF Val66Met have reported inconsistent statistically significant associations, as well as inconsistencies regarding the direction of the genotype effects across individual studies (Harrisberger et al. 2014, 2015).

Two recent large meta-analyses suggest that the analysis of hippocampal subfield volumes may allow for more accurate detection of genetic effects in genetic association analyses, compared with whole hippocampal volume (van der Meer et al. 2018; Hibar et al. 2017). Moreover, previous studies have shown that different pathological conditions affect subfields differently (West et al. 1994; Jin et al. 2004; Ezzati et al. 2014; Mueller et al. 2010; Hett et al. 2018). In fact, the proven differential expression of BDNF and its receptors in different regions of the hippocampus (Kowiański et al. 2018; Vilar and Mira 2016; Franzmeier et al. 2019), reinforces distinct biological functions of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on the different subfields. However, to our knowledge no previous studies have addressed the effects of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on hippocampal subfields in cognitively unimpaired (CU) individuals. Most of the studies addressing the association of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and hippocampal volumes (subfields and/or whole hippocampus) included patients of a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders, such as major depressive disorder, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Zeni et al. 2016; Cao et al. 2016; Reinhart et al. 2015; Aas et al. 2014; Frodl et al. 2014), showing also inconsistencies concerning the impact of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms (Tsai 2018).

The ε4 allele of apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, the major genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Mueller and Weiner 2009), has also an impact on hippocampal subfields. APOE ε4-carriers have reduced volume of the subicular/CA1 region in AD patients (Pievani et al. 2011), as well as in a pool of older adults that included healthy controls and patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI) and AD dementia, after controlling for the diagnostic group (Kerchner et al. 2014). In a recent report in CU participants, we also showed that APOE-ε4 relates to significantly reduced hippocampal tail in a gene dose-dependent manner (Cacciaglia et al. 2018a).

Moreover, recent evidence suggests that APOE genotypes differentially affects the expression of BDNF through the regulation of its maturation in human astrocytes and its secretion (Sen, Nelson, and Alkon 2015). Astrocytes are known to synthesise BDNF, and as brain APOE is primarily produced by astrocytes, studying APOE and BDNF modulation becomes important. Specifically, interactions between APOE-ε4 and BDNF have been suggested to influence their secondary effects on AD pathology (Álvarez et al. 2014), and their influence on hippocampal volume (Li et al. 2016; Shi et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2015a, b). In addition, a significant combined effect of APOE-ε4 and BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms has been reported to moderate β-amyloid-related cognitive decline in preclinical AD (Lim et al. 2015). Episodic memory performance was also found to be impaired in MCI/AD individuals who were also carriers of both the APOE-ε4 and BDNF Met polymorphisms (Gomar et al. 2016), as well as in healthy individuals (Ward et al. 2014). Overall, evidence suggests biological interactions between APOE and BDNF for memory and other brain-related processes that may help to explain the increased AD risk in APOE-ε4 carriers during the period that precedes the development of symptoms.

Therefore, the aim of the present study is to evaluate the impact of Val66Met polymorphism on hippocampal subfields in a large sample of in middle-age cognitively unimpaired individuals CU participants and to assess whether an interactive effect with the APOE-ε4 genotype exists.

Materials and methods

Study population and setting

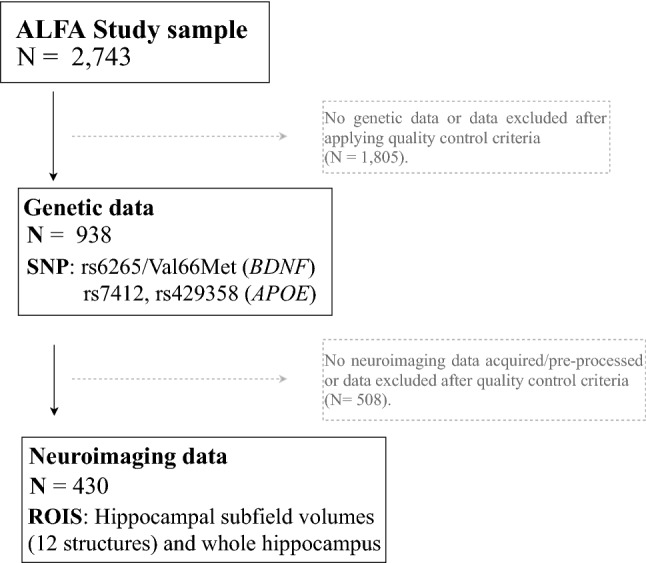

Participants were drawn from the ALFA study (Alzheimer and FAmilies) established at the Barcelonaβeta Brain Research Center (Molinuevo et al. 2016), which aims at identifying the neuroimaging and cognitive signatures in preclinical AD. The ALFA study (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01835717) entangles a cohort of 2,743 cognitively unimpaired participants, mostly adult children of patients with AD, and aged between 45 and 75 years. Cognitive status was assessed at baseline as follows: Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein et al. 1975; Blesa et al. 2001) > 26, Memory Impairment Screen (Buschke et al. 1999; Böhm et al. 2005) > 6, Time-Orientation subtest of the Barcelona Test II (Quinones-Ubeda 2009) > 68, semantic fluency (Ramier and Hecaen 1970; Peña-Casanova et al. 2009) (animals) > 12 and Clinical Dementia Rating scale (Morris 1993) = 0. A subset of 430 participants from the ALFA study with available information on BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms and APOE genotypes, as well as neuroimaging data (HSv) were included in this study (Fig. 1). The cognitive status of these participants was reviewed if cognitive testing had not been conducted in the last 6 months. For this, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was ruled out by clinical judgment after interview and accounting for psychometric scores in the main variables of the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test [FCSRT] (Buschke et al. 2017). The study was conducted in accordance with the directives of the Spanish Law 14/2007, of 3rd of July, on Biomedical Research (Ley 14/2007 de Investigación Biomédica). All participants accepted the study procedures by signing an informed consent form. A subset of 430 participants from the ALFA study with available information on BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms and APOE genotypes, as well as neuroimaging data (HSv) were included in this study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart depicting the final sample size of the real application. Solid lines and boxes represent individuals remaining in the study. Dashed lines and boxes represent individuals excluded. Reason and number of individuals excluded is indicated in dashed boxes. SNP single nucleotide polymorphism, N size of the sample, ROIS brain regions of interest

Genotyping

DNA samples were obtained from whole blood samples by applying salting out protocol. DNA was eluted in 800 µl of H2O (milliQ) and quantified using Quant-iTT PicoGreen® dsDNA Assay Kit (Life Technologies). Integrity of DNA was checked in a subset of samples by running a 1% agarose gel. All the samples were within specification. Genome-wide genotyping was performed using the NeuroChip backbone(Blauwendraat et al. 2017), based on a genome-wide genotyping array (Infinium HumanCore-24 v1.0) containing 306,670 tagging variants and a custom content that has been updated and extended with 179,467 neurodegenerative disease-related variants at the Cancer Epigenetics and Biology Program (PEBC; IDIBELL). Previous step was to normalize the quantity of DNA from each sample. The analysis was performed by the GenomeStudio (Illumina) software using the genotyping module (standard analysis). PLINK was used for genetic data quality control (Purcell et al. 2007). We applied the following sample quality control thresholds: sample call rate > 97% (N = 6 exclusion) and heterozygosity 5 SD (N = 8 exclusions). Then, we checked sex discordances (N = 4 exclusions). In total, we excluded 18 subjects (less than 2%). None of the individuals presented autosomal dominant mutations in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2. The final genetic data set consisted of volunteers of European ethnic origin with available information regarding BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and the APOE rs429358 and rs7412 polymorphisms. Genotype and allele frequencies of Val66Met, rs429358 and rs7412 polymorphisms were determined. Moreover, allele frequencies were inspected for potential covariate-related differences. Departures from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium were also examined (Ryckman and Williams 2008). The APOE allelic variants were obtained from allelic combinations of the rs429358 and rs7412 polymorphism (Radmanesh et al. 2014). According to the genotypes of these polymorphisms, subjects were classified depending on the number of ε4 alleles (non-carriers, one ε4 allele or two ε4 alleles).

Image acquisition and extraction of hippocampal subfield volumes

Scans were obtained with a 3 T scanner (Philips Ingenia CX). The MRI protocol was identical for all participants and included high-resolution three-dimensional structural images weighted in T1 with an isotropic voxel of 0.75 × 075 × 0.75 mm3. The acquisition parameters were TR/TE/TI = 9.9/4.6/900 ms, flip angle = 8° and a matrix size of 320 × 320 × 240. Hippocampal subfields were segmented using FreeSurfer version 6.0 (Iglesias et al. 2015). We extracted raw volumes for 12 different HSv per hemisphere: the cornu ammonis region 1 (CA1), cornu ammonis region 2/3 (CA3), cornu ammonis region 4 (CA4), dentate gyrus (DG), fimbria, hippocampal-amygdaloid transition area (hata), tail, parasubiculum, presubiculum, subiculum, fissure and molecular layer. The value of the subfields used as the outcomes of the study were calculated as the sum of the regional value of each hemisphere (mm3). We visually inspected the segmentation of the individuals included in the study (Fig. 2), and we removed outliers and/or abnormal hippocampal subfields volume values. The whole hippocampal volume, as well as, total intracranial volume were also calculated using Freesurfer (v. 6.0).

Fig. 2.

T1 images of hippocampal segmentation

Statistical analysis

Differences in demographic variables were tested using χ2 test and F test for gender, age, education, number of APOE-ε4 carriers and total intracranial volume (TIV). The additive, dominant, recessive, and codominant effects of the BDNF Val66Met genotype on the hippocampal subfields volume were assessed using general linear models corrected by age, sex, years of education, number of APOE-ε4 alleles and TIV. These covariates were selected based on previous associations reported using the ALFA study sample (Cacciaglia et al. 2018b). In brief, the genetic additive model predicts a linear increase of the phenotypic variable depending on the number of Met alleles, whereas the codominant genetic model infers that the heterozygote mean differs from both the homozygote means. The dominant genetic model assumes a common response to 1 or 2 copies of the Met allele. Finally, a recessive genetic model predicts a common response to 0 or 1 copies of the Met allele.

The assumption of different genetic models was performed to counteract a misspecification of the true underlying genetic model, which could have an adverse effect on the statistical power of an association, and on the effect size (Gaye and Davis 2017). The goodness-of-fit of each genetic model was evaluated based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC), for which lower numerical values indicate a better fit of the model (Akaike 1998).

We also investigated whether the association between BDNF Val66Met and hippocampal subfield volumes was modified by the number of APOE-ε4 alleles, with a second model that included an interaction term between BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and the number of ε4 alleles, co-varying for age, sex, years of education and total intracranial volume potential confounders. In this model, dominant genetic effects were assumed for Val66Met polymorphism and additive genetic effects for APOE-ε4 alleles.

Moreover, in post-hoc analyses, we evaluated the effects of BDNF Val66Met and APOE-ε4 status on cognitive performance.

Statistical significance was set at False Discovery Rate (FDR) corrected p value < 0.05, and all statistical analyses and data visualization were carried out using R version 3.4.4.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Descriptive data of the demographic and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism information are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The mean age of the population was 57.1 ± 5.7 years old, with 61.4% women. The BDNF Val66Met genotype groups did not significantly differ in the distribution of gender (χ2[2] = 0.55, p: 0.51), number of APOE-ε4 alleles (χ2[2] = 6.13, p = 0.19), age (F[2,427] = 0.67, p: 0.76), years of education (F[2,247] = 0.107, p: 0.9), or total intracranial volume (TIV) (F[2,427] = 1.66, p: 0.19). The distribution of BDNF Val66Met and APOE rs429358 and rs7412 polymorphisms did not deviate from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (χ2[1] = 0.42, p: 0.51). Table 3 summarizes the hippocampal subfield volumes analyzed in the study by BDNF genotype. All morphometric subfield measures were normally distributed (Kolmogorov Smirnov test, FDR > 0.05) and their variances were homogenous (Levene’s test, FDR > 0.05). Figure S1 shows the pattern of correlation (Pearson correlation statistics) among all subfields included in the study. Hippocampal subfield structures present high correlation among them (r > 0.8) (i.e., structural covariance).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study according to rs6265 (Val/Met) status

| ValVal carriers (n = 247) | ValMet carriers (n = 161) | MetMet carriers (n = 22) | Total (n = 430) | Statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (m ± SD; years) | 57.31 (5.63) | 56.93 (5.84) | 55.97 (5.82) | 57.1 (5.72) | F (2.427) = 0.67 | 0.76 |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 154 (62.35%) | 98 (60.87%) | 12 (54.55%) | 264 (61.4%) | Chi (2) = 0.549 | 0.512 |

| Education (m ± SD; years) | 13.87 (± 3.53) | 14.03 (± 3.53) | 13.95 (± 3.5) | 13.93 (± 3.52) | F (2.427) = 0.107 | 0.899 |

| Number of APOE-ε4 alleles, n (%) | 0: 160 (64.78%); 1: 75 (30.36%); 2: 12 (4.86%) | 0: 89 (55.28%); 1: 59 (36.65%); 2: 13 (8.07%) | 0: 12 (54.55%); 1: 7 (31.82%); 2: 3 (13.64%) | 0: 261 (60.7%); 1: 141 (32.79%); 2: 28 (6.51%) | Chi (2) = 6.129 | 0.19 |

| TIV (m ± SD; cm3) | 1442.91 (± 177.13) | 1453.1 (± 163.66) | 1511.62 (± 163.28) | 1450.24 (± 171.79) | F (2.427) = 1.656 | 0.192 |

Mean and SD are shown for continuous variables

n sample size, m mean, SD standard deviation, TIV total intracranial volume P p value

Table 2.

Characteristics of BDNF Val66Met and APOE polymorphisms

| Gene | SNP | CHR | position | Allele 1 | Allele 2 | MAF | MAF gp* | Genotype distribution | HWE | Array** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF | Val66Met (rs6265) | 11 | 27,658,369 (CRCh37) | C [Val] | T [Met] | 0.238 | 0.19,437 | ValVal: 247 / ValMet: 161 / MetMet: 22 | 0.51 | Neurochip backbone (Infinium HumanCore-24 v1.0) |

| Allele ε4 distribution | ||||||||||

| APOE | rs429358 | 19 | 45,411,941 (CRCh37) | T | C | 0.214 | 0.138 | ε4-non carriers: 261; ε4 heterozygous: 141; ε4 homozygous: 28 | 0.137 | |

| rs7412 | 19 | 45,412,079 (CRCh37) | C | T | 0.043 | 0.061 | ||||

SNP single nucleotide polymorphisms, BP base position, A1 major allele, A2 minor allele, MAF minor allele frequency, MAF gp* MAF general population. Source: gnomAD genome aggregation database, HWE Hardy weinberg equilibrium

Array source** Blauwendraat et al., NeuroChip, an updated version of the NeuroX genotyping platform to rapidly screen for variants associated with neurological diseases. Neurobiology of Aging. 2017 vol: 57 pp: 247.e9-247.e13

Table 3.

Characteristics of hippocampal subfield volumes

| Hippocampal subfield | ValVal carriers (n = 247) | ValMet carriers (n = 161) | MetMet carriers (n = 22) | Total (n = 430) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Min | Median | Max | Mean (SD) | Min | Median | Max | Mean (SD) | Min | Median | Max | Mean (SD) | Min | Median | Max | |

| CA1, mm3 | 1193 (123) | 920 | 1176 | 1595 | 1214 (119) | 950 | 1207 | 1518 | 1255 (161) | 924 | 1250 | 1630 | 1204 (124) | 920 | 1192 | 1630 |

| CA3, mm3 | 361 (42) | 241 | 357 | 511 | 364 (40) | 273 | 361 | 475 | 385 (62) | 299 | 375 | 525 | 364 (43) | 241 | 358 | 525 |

| CA4, mm3 | 454 (44) | 299 | 448 | 594 | 459 (38) | 374 | 458 | 564 | 480 (59) | 377 | 464 | 619 | 457 (43) | 299 | 455 | 619 |

| GC-ML-DG, mm3 | 535 (52) | 351 | 530 | 706 | 541 (45) | 432 | 535 | 656 | 566 (67) | 450 | 553 | 724 | 539 (51) | 351 | 533 | 724 |

| Subiculum, mm3 | 802 (91) | 594 | 804 | 1113 | 822 (86) | 639 | 816 | 1067 | 866 (104) | 688 | 859 | 1061 | 812 (91) | 594 | 809 | 1113 |

| Presubiculum, mm3 | 601 (69) | 412 | 599 | 797 | 614 (60) | 482 | 616 | 786 | 630 (75) | 528 | 616 | 781 | 608 (66) | 412 | 604 | 797 |

| Parasubiculum, mm3 | 125 (18) | 83 | 123 | 194 | 127 (17) | 92 | 125 | 175 | 131 (21) | 94 | 127 | 194 | 126 (18) | 83 | 125 | 194 |

| Hippocampal fissure, mm3 | 339 (45) | 214 | 338 | 514 | 345 (40) | 255 | 346 | 448 | 360 (50) | 293 | 348 | 457 | 343 (44) | 214 | 341 | 514 |

| Hippocampal tail, mm3 | 1068 (126) | 767 | 1058 | 1388 | 1086 (128) | 808 | 1087 | 1488 | 1080 (133) | 787 | 1069 | 1328 | 1076 (127) | 767 | 1066 | 1488 |

| Fimbria, mm3 | 174 (30) | 108 | 173 | 308 | 175 (30) | 105 | 175 | 267 | 182 (29) | 132 | 181 | 241 | 175 (30) | 105 | 174 | 308 |

| Hata, mm3 | 117 (14) | 72 | 116 | 179 | 118 (13) | 83 | 117 | 156 | 120 (16) | 85 | 119 | 147 | 118 (14) | 72 | 117 | 179 |

| Molecular layer, mm3 | 1059 (99) | 767 | 1052 | 1311 | 1077 (93) | 889 | 1070 | 1328 | 1121 (122) | 910 | 1110 | 1404 | 1069 (99) | 767 | 1061 | 1404 |

| whole hippocampus, mm3 | 6489 (597) | 4623 | 6435 | 8235 | 6598 (552) | 5407 | 6567 | 8014 | 6817 (747) | 5351 | 6793 | 8582 | 6547 (594) | 4623 | 6492 | 8582 |

Means, standard deviations (SD), Median, and ranges values are shown

Segmentation of hippocampal subfields performed with FreeSurfer version 6.0 image analysis suite

CA1 cornu ammonis region 1, CA3 cornu ammonis region 23, CA4 cornu ammonis region 4, GC-ML-DG granule cells in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus, hata hippocampal-amygdaloid transition region, HP hippocampus, CI95 confidence interval, FDR95 false discovery rate corrected p value < 0.05

Effect of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on hippocampal subfields

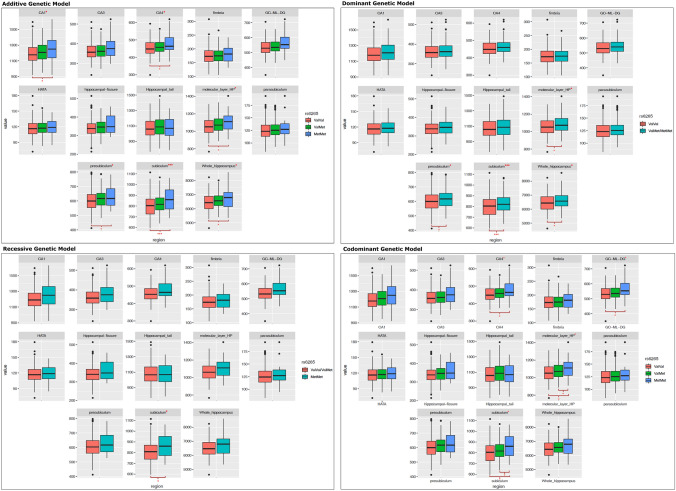

General linear models revealed that Met carriers showed statistically significant larger bilateral volumes of the subiculum under the dominant model (= 2.53%, = 3 × ) (Table 4 and Fig. 3). For subiculum subfield, an additive genetic model obtained the lowest AICs score (AIC = 4890.43), indicating that this model is the most parsimonious model for this subfield structure. Moreover, we found statistically significant larger bilateral volumes of the subiculum under the additive genetic model (= 2.39%, = 0.013) (Table S1). No significant results after FDR-correction were found under recessive and codominant genetic models. In addition, nominal significant results without FDR adjustment (p < 0.05) showed larger bilateral volumes of the molecular layer of the hippocampus (β: 1.55%, p: 0.007), presubiculum (β: 1.74%, p: 0.041), and whole hippocampal volume (β: 1.46%, p: 0.025) for Met carriers under the dominant genetic model. Results of all adjusted genetic models for each HSv can be found in Table S1.

Table 4.

Main effects of Val66Met genotype on hippocampal subfields (mm3)

| Hippocampal subfield | Best genetic model | Effect (mm3) | CI 95% | Effect (%) | p value | FDR95% | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA1 | Dominant | 18.575 | (− 0.67, 37.82) | 1.54% | 0.059 | 0.531 | 5188.564 |

| CA3 | Recessive | 14.291 | (− 1.43, 30.01) | 3.93% | 0.076 | 0.684 | 4321.049 |

| CA4 | Recessive | 14.04 | (− 0.69, 28.77) | 3.07% | 0.062 | 0.671 | 4264.9 |

| GC-ML-DG | Recessive | 16.756 | (− 0.19, 33.71) | 3.11% | 0.053 | 0.636 | 4385.858 |

| Subiculum | Additive | 19.435 | (8.06, 30.81) | 2.39% | 0.001 | 0.013* | 4890.434 |

| Presubiculum | Dominant | 10.556 | (0.44, 20.67) | 1.74% | 0.041 | 0.41 | 4635.326 |

| Parasubiculum | Dominant | 1.845 | (− 1.06, 4.75) | 1.46% | 0.214 | 1 | 3562.288 |

| Hippocampal fissure | Dominant | 5.226 | (− 2.05, 12.5) | 1.52% | 0.16 | 1 | 4351.502 |

| Hippoccampal tail | Dominant | 12.37 | (− 9.43, 34.17) | 1.15% | 0.267 | 1 | 5295.52 |

| Fimbria | Recessive | 1.601 | (− 10.09, 13.29) | 0.91% | 0.789 | 1 | 4065.996 |

| Hata | Dominant | 0.333 | (− 1.95, 2.61) | 0.28% | 0.775 | 1 | 3354.183 |

| Molecular layer | Additive | 16.578 | (4.59, 28.57) | 1.55% | 0.007 | 0.084 | 4937.902 |

| Whole hippocampus | Dominant | 95.904 | (12.06, 179.75) | 1.46% | 0.025 | 0.275 | 6454.188 |

All models were adjusted by sex, years of education, number of APOE-ε4 allele and total intracranial volume

CA1 cornu ammonis region 1, CA3 cornu ammonis region 23, CA4 cornu ammonis region 4, GC-ML-DG granule cells in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus, hata hippocampal-amygdaloid transition region, HP hippocampus, CI95 confidence interval, FDR95 false discovery rate corrected p value < 0.05. AIC akaike information criterion

Fig. 3.

Box plot of change in hippocampal subfield volumes between BDNF Val66Met (rs6265) genotypes under additive, dominant, recessive and codominant genetic models. Middle line in box represents the median; lower box bounds the first quartile; upper box bounds the 3rd quartile. Whiskers represent the 95% confidence interval of the mean. Open circles are outliers from 95% confidence interval. *Significant difference between groups at a nominal level (p < 0.05). ***Significant difference between groups after multiple comparison correction (FDR < 0.05). CA1 cornu ammonis region 1, CA3 cornu ammonis region 3, CA4 cornu ammonis region 4, GC-ML-DG granule cells in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus, hata hippocampal-amygdaloid transition region, HP hippocampus

Effect of the interaction between APOE-ε4 and BDNF Val66Met on hippocampal subfields

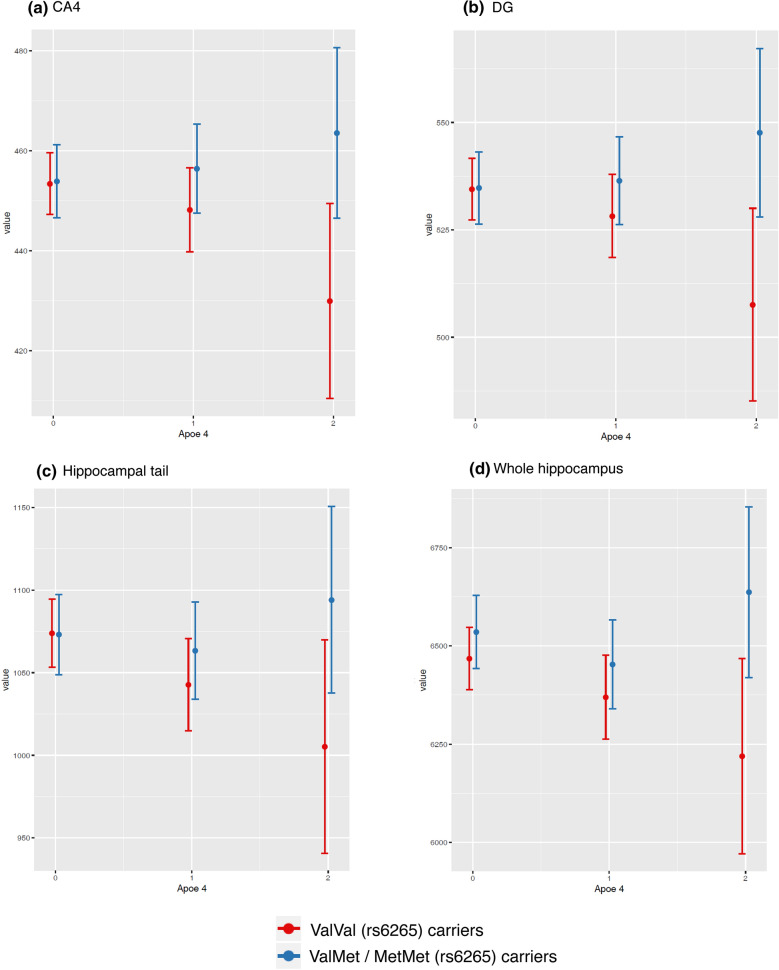

As expected, APOE ε4 allele was associated with lower bilateral volumes of the hippocampal subfields, even though on a trend-level (Table S2). Interestingly, when this association was studied according to BDNF Val66Met genotypes, we observed a significant interaction with the presence of Met alleles (p < 0.05) (Table 5). APOE-ε4 homozygotes carrying at least one Met allele presented nominally significant larger bilateral volumes of the CA4 (β: 7.25%, p: 0.016) and DG (β: 7.38%, p: 0.012) subfields, hippocampal tail (β: 8.33%, p: 0.05), and whole hippocampal volumes (β: 5.35%, p: 0.046) than the expected combined effect of the individual contribution of APOE-ε4 (reverse effect) and BDNF Val66Met (Fig. 4). Moreover, even though the results for the remainder hippocampal subfields were statistically not significant, changes on hippocampal subfields volumes follow the same general patterns (Figure S2).

Table 5.

Interaction Effects Between number of APOE-ε4 alleles (under additive model) and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism (under dominant genetic model) on hippocampal subfields

| Hippocampal subfield | Dominant genetic model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect (mm3) | CI 95% | Effect (%) | p value | FDR95% | |

| CA1 | − 10.788 | (− 52.36, 30.79) | − 0.90% | 0.611 | 1 |

| 55.535 | (− 23.33, 134.4) | 4.61% | 0.168 | 1 | |

| CA3 | 10.889 | (− 4.31, 26.09) | 2.99% | 0.161 | 1 |

| 27.425 | (− 1.4, 56.25) | 7.53% | 0.063 | 0.567 | |

| CA4 | 7.797 | (− 6.39, 21.98) | 1.71% | 0.282 | 1 |

| 33.155 | (6.25, 60.06) | 7.25% | 0.016 | 0.192 | |

| GC-ML-DG | 7.94 | (− 8.39, 24.27) | 1.47% | 0.341 | 1 |

| 39.772 | (8.79, 70.75) | 7.38% | 0.012 | 0.156 | |

| Subiculum | − 13.434 | (− 42.9, 16.03) | − 1.65% | 0.372 | 1 |

| 25.529 | (− 30.36, 81.42) | 3.14% | 0.371 | 1 | |

| Presubiculum | 0.013 | (− 21.92, 21.94) | ~ 0% | 0.999 | 1 |

| 13.726 | (− 27.87, 55.33) | 2.26% | 0.518 | 1 | |

| Parasubiculum | 2.587 | (− 3.7, 8.88) | 2.05% | 0.421 | 1 |

| 2.78 | (− 9.15, 14.71) | 2.21% | 0.648 | 1 | |

| Hippocampal fissure | − 1.375 | (− 17.1, 14.35) | − 0.40% | 0.864 | 1 |

| 7.756 | (− 22.08, 37.59) | 2.26% | 0.611 | 1 | |

| Hippoccampal tail | 21.561 | (− 25.48, 68.6) | 2.00% | 0.369 | 1 |

| 89.676 | (0.45, 178.9) | 8.33% | 0.05 | 0.506 | |

| Fimbria | − 7.8 | (− 19.07, 3.47) | − 4.46% | 0.176 | 1 |

| 8.845 | (− 12.54, 30.23) | 5.05% | 0.418 | 1 | |

| Hata | − 0.304 | (− 5.25, 4.64) | − 0.26% | 0.904 | 1 |

| 4.091 | (− 5.29, 13.47) | 3.47% | 0.393 | 1 | |

| Molecular layer | − 2.31 | (− 33.37, 28.75) | − 0.22% | 0.884 | 1 |

| 49.911 | (− 9.01, 108.83) | 4.67% | 0.098 | 0.784 | |

| Whole hippocampus | 16.151 | (− 164.67, 196.97) | 0.25% | 0.861 | 1 |

| 350.445 | (7.43, 693.46) | 5.35% | 0.046 | 0.506 | |

All models were adjusted by sex, years of education, age and total intracranial volume

CA1 cornu ammonis region 1, CA3 cornu ammonis region 23 CA4 cornu ammonis region 4, GC-ML-DG granule cells in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus, hata hippocampal-amygdaloid transition region, HP hippocampus, CI95 confidence interval, FDR95 FDR corrected p value < 0.05

Fig. 4.

Differences according BDNF Val66Met genotypes in associations between APOE-ε4 and a Cornu ammonis region 4 (CA4) subfield volume, b Granule cells in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (GC-ML-DG) subfield volume, c hippocampal tail subfield volume, and d whole hippocampal volume

Post-hoc analyses: Effect of BDNF Val66Met and APOE-ε4 on cognitive performance

The post hoc analyses, although not significant, suggested better cognitive performance patterns for Met carriers in most FCSRT domains, and in depression scores of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Table 6). In addition, APOE-ε4 status did not significantly influence the effects of BDNF Val66Met genotypes on cognitive performance.

Table 6.

Main and interaction effects of BDNF-Val66Met genotype and APOE-ε4 status (dominant model) on cognitive performance (HADS, FCSRT tests)

| Cognition (Test) | Effect | CI 95% | p value | FDR-95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS-anxiety | ||||

| Val66Met | − 0.040 | (− 0.29, 0.21) | 0.756 | |

| APOE-ε4 | − 0.188 | (− 0.59, 0.22) | 0.364 | |

| Val66Met x APOE-ε4 | 0.243 | 1 | ||

| HADS-depression | 0.318 | |||

| Val66Met | 0.036 | (− 0.43, 0.5) | 0.879 | |

| APOE-ε4 | 0.32 | (− 0.36, 0.99) | 0.354 | |

| Val66Met x APOE-ε4 | 0.318 | 1 | ||

| Delayed recall (DR) | ||||

| Val66Met | 0.143 | (− 0.29, 0.57) | 0,517 | |

| APOE-ε4 | 0.067 | (− 0.61, 0.74) | 0.847 | |

| Val66Met x APOE-ε4 | 0.85 | 1 | ||

| Total recall (TR) | ||||

| Val66Met | 0.111 | (− 1.22, 1.44) | 0.87 | |

| APOE-ε4 | 1.398 | (− 0.67, 3.47) | 0.188 | |

| Val66Met x APOE-ε4 | 0.45 | 1 | ||

| Delayed free recall (DFR) | ||||

| Val66Met | − 0.513 | (− 1.30, 0.27) | 0.204 | |

| APOE-ε4 | 0.528 | (− 0.69, 1.75) | 0.4 | |

| Val66Met x APOE-ε4 | 0.722 | 1 | ||

| Free recall (FR) | ||||

| Val66Met | 2.099 | (− 2.4, 6.59) | 0.387 | |

| APOE-ε4 | − 0.853 | (− 6.367, 4.662) | 0.77 | |

| Val66Met x APOE-ε4 | 0.385 | 1 | ||

| Retention index | ||||

| Val66Met | − 0.029 | (− 0.091, 0.033) | 0.391 | |

| APOE-ε4 | − 0.008 | (− 0.085, 0.068) | 0.837 | |

| Val66Met x APOE-ε4 | 0.948 | 1 | ||

All models were adjusted by sex, years of education, and total intracranial volume

CI95 confidence interval, FDR95 FDR corrected p value < 0.05, HADS hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), HADS-Anxiety anxiety score of the HADS, HADS-Depression depression score of the HADS, FCSRT free and cued selective reminding test

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show a phenotypic effect of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism in the hippocampal subfields of cognitively unimpaired (CU) individuals. Moreover, the present study is also the first in CU to find an effect modification by BDNF Val66Met polymorphism of associations between APOE-ε4 status and hippocampal subfield volumes.

We first found significantly larger bilateral subiculum volumes in CU middle-aged/late-middle-aged BDNF Val66Met carriers in a dose-dependent manner. The direction of the effects is consistent across different subfields and the entire hippocampal formation, as shown by the nominally significant difference between BDNF Val66Met carriers and non-carriers involving the molecular layer of the hippocampus, as well as the pre-subiculum and the whole hippocampus.

Given that BDNF Val66Met polymorphism has been related to impaired hippocampal long-term potentiation which underlies learning and memory (Spriggs et al. 2018), our results may underline compensatory mechanisms in the Met-carriers to achieve normative episodic recall, which is highly specialized in the subiculum (Eldridge et al. 2005; Suthana et al. 2015). However, although most studies showed that large hippocampal volumes lead to better memory performance and may protect from dementia (Pohlack et al. 2014; Whitwell 2010; Erten-Lyons et al. 2009), the impact of hippocampal volume on cognitive performance in middle-aged CU individual’s remains controversial. For instance, smaller hippocampal volumes have been related to better episodic memory, due to efficient synaptic pruning (Van Petten 2004). Thus, our results could suggest a moderating role of BDNF in the neurobiology of hippocampal subfields, which may stress the importance to consider the hippocampal formation at the subfield level to disentangle potential opposite effects leading to the aforementioned conflicting results. In addition, we cannot rule out that the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism may differentially influence the morphology of other brain areas. This calls for additional whole-brain voxel-wise studies addressing distinct genetic models of penetrance of BDNF Val66Met.

Second, we also observed that Met-carriers compensate for the deleterious impact of the number of APOE-ε4 alleles on hippocampal subfield volumes. As expected, we observed that APOE-ε4 homozygotes showed a tendency towards displaying reduced volumes of the subiculum and hippocampal tails, in accordance with previous reports (Kerchner et al. 2014; Cacciaglia et al. 2018a; Pievani et al. 2011). These individuals are at increased higher risk (× 15) to develop AD as compared to APOE-ε4 non-carriers. The lower hippocampal volumes in APOE-ε4 carriers are often interpreted as brain marker that confers vulnerability towards developing the clinical picture of AD. Strikingly, we found that APOE-ε4 homozygotes who were also Met-carriers countered the effect of the APOE genotype and presented HSv within the ranges expected for APOE-ε4 non-carriers, particularly in the CA4, GC-ML-DG and the hippocampal tails. It could be argued that Met-carriers can counter the deleterious effect of the APOE-ε4 genotype in the age range of the studied sample.

Another possible explanation to this finding could raise from an interaction of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism with pathological markers of AD, as the APOE-ε4 allele has also been strongly linked to a dose-dependent increase in the prevalence of abnormally elevated cerebral amyloid deposition in CU individuals (Reiman et al. 2009). By the mean age of our APOE-ε4 homozygote group (56.62 ± 5.71y), about half of them are expected to display abnormally high amyloid levels (Jansen et al. 2015). However, previous longitudinal reports on amyloid-positive CU individuals have described that the BDNF Val66Met allele was associated with a steeper decline in cognitive function and hippocampal atrophy (Yen Ying Lim et al. 2013). Moreover, this deleterious effect is more severe in APOE-ε4 carriers (Lim et al. 2015). These studies, however, were performed in significantly older cohorts (average age of 70y) than that in our work. Another recent study performed in subjects with an age range similar to ours (55y) confirmed this longitudinal pattern of decline in cognition, particularly in amyloid-positive CU individuals (Boots et al. 2017). However, in this work, Boots et al. also reported that, at baseline, Met carriers showed a significantly better cognitive performance (verbal learning and memory, speed and flexibility, and working memory), even if amyloid positive. Similar patterns of effect were observed in our sample. Specifically, we found that Met carriers suggested patterns of better cognitive performance on the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) domains, and on the Depression score of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Although these differences were not statistically significant, one potential explanation to reconcile our findings with the existing literature would be that the Met genotype might provide a limited beneficial effect during middle age. When no longer capable of compensating for the deleterious downstream effects of amyloid accumulation, then Met carriers would experience faster hippocampal atrophy and a steeper decline in cognition. Neither shall it be excluded that APOE-ε4 and Met carriers could be the most vulnerable to an inflammatory response at the beginning of the amyloid-pathology. Nevertheless, the current unavailability of core AD biomarkers and the cross-sectional nature of this study constitute a limitation for the full interpretation of the interaction between the BDNF Met and APOE-ε4 genotypes. Nevertheless, this will be mitigated in the longitudinal follow-up of the cohort here studied, as a subset of our participants will undergo a lumbar puncture to assess cerebrospinal fluid levels of core AD biomarkers (Aβ42, total Tau, and phosphorylated Tau).

A strong feature of our study that may sustain our ability to detect a significant effect of Val66Met genotype (and its interaction with APOE) on hippocampal subfields is that the studied cohort presents a higher prevalence of BDNF Met and APOE-ε4 homozygotes compared with previous studies. While most of the studies reported allele frequencies between 0% (studies without MetMet carriers) to 6% (Harrisberger et al. 2015), the minor allele frequency in our study achieves 23%, which is even higher to the population frequency (15–19%, Source: Genome Aggregation Database https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/variant/11-27679916-C-T). Similarly, the high number of APOE-ε4 carriers in the ALFA participants compared to the general population (19% vs. 14%, respectively; p < 0.001) has allowed us to disentangle specific effects in ε4 homozygotes, while most studies pool them with heterozygotes in a single APOE-ε4 carrier group. In our study, the high prevalence of these less frequent genotypes has allowed us to achieve a relatively higher inferential power, allowing for testing additive, recessive and codominant genetic effects, as well as, gene–gene interactions.

Another substantial strength is the use of a high-resolution T1 scan as compared to previous studies, combined with the use of the most recent version (v.6.0) of the hippocampal subfield segmentation toolbox in Freesurfer, which overcomes significant shortcomings of previous versions (Iglesias et al. 2015; Wisse et al. 2014; Mueller et al. 2018). Thus, subfield volumes available for this analysis are of substantially better quality, which, combined with a considerably higher sample size, has allowed us to achieve a significantly superior statistical power than previous reports. Moreover, only a few studies have assessed hippocampal subfield volumes and compared them to whole hippocampal volumetry, even though the independent genetic variation specific to hippocampal subfields (Elman et al. 2019). Thus, our analyses based on hippocampal subfields increased the sensitivity of the results, which make our study more robust and consistent than previous ones.

Finally, in contrast to previous studies in which the diagnostic value of hippocampal subfield volumes related to Val66Met polymorphism was only assessed by comparing patients with psychiatric disorders, our study includes CU middle-aged/late-middle-age participants. This is also a relevant strength because the misrepresentation of the general population could constitute a bias in the assessment of the diagnostic utility of hippocampal subfield volumes, due to potential etiologies associated with neurodegenerative processes (de Flores et al. 2015).

Altogether, our findings suggest that the BDNF Met allele might confer a time-limited resilience, which protects the hippocampi from the downstream deleterious effects of ageing and/or amyloid accumulation, thus mediating the risk effect of APOE-ε4. Hence, these results prompt us to further explore hippocampal atrophy rates and cognitive trajectories of BDNF Met carriers compared to Val homozygotes, also as a function of their APOE genotype and long-term accumulation of amyloid beta.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (PDF 13 kb)Figure S1. Heatmap showing pair correlations across brain structures of ALFA project subsample, with blue color indicating positive correlations and red colour indicating negative correlations. Legend: CA1, cornu ammonis region 1; CA23, cornu ammonis region 23; CA4, cornu ammonis region 4; GC-ML-DG, granule cells in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus; hata, hippocampal-amygdaloid transition region; HP, hippocampus.

Supplementary file2 (PDF 257 kb) Figure S2. Differences according BDNF Val66Met genotypes in associations between APOE-ε4 and the remaining subfields. Legend: CA1, cornu ammonis region 1; CA23, cornu ammonis region 23; hata, hippocampal-amygdaloid transition region.

Supplementary file3 (DOCX 21 kb) Table S1. Main effects of Val66Met genotype on hippocampal subfields (mm3). All models were adjusted by sex, years of education, number of APOE-e4 allele and total intracranial volume.

Supplementary file4 (DOCX 14 kb) Table S2. Main effects of number of APOE-e4 alleles on hippocampal subfields (mm3). All models were adjusted by sex, years of education, age, val66Met genotypes and total intracranial volume.

Acknowledgements

NV-T is funded by a post-doctoral grant, Juan de la Cierva Programme (FJC2018-038085-I), Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades – Spanish State Research Agency. The research leading to these results has received funding from “la Caixa” Foundation (LCF/PR/GN17/10300004) and the Health Department of the Catalan Government (Health Research and Innovation Strategic Plan (PERIS) 2016–2020 grant# SLT002/16/00201). CM was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant n° IEDI-2016-00690). MSC received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie action grant agreement No 752310. H.H.H.A. was supported by ZonMW grant numbers 916.19.15 and 916.19.151. J.D.G. holds a ‘Ramón y Cajal’ fellowship (RYC-2013-13054). This publication is part of the ALFA (ALzheimer and FAmilies) study. The authors would like to express their most sincere gratitude to the ALFA project participants, without whom this research would have not been possible. With recognition and heartfelt gratitude to Mrs. Blanca Brillas for her outstanding and continued support to the Pasqual Maragall Foundation to make possible a Future without Alzheimer´s. Collaborators of the ALFA study are: Eider M. Arenaza-Urquijo, Annabella Beteta, Anna Brugulat-Serrat, Alba Cañas, Carme Deulofeu, Ruth Dominguez, Maria Emilio, Karine Fauria, Sherezade Fuentes, Laura Hernandez, Gema Huesa, Jordi Huguet, Paula Marne, Tania Menchón, Albina Polo, Sandra Pradas, Aleix Sala-Vila, Gonzalo Sánchez-Benavides, Anna Soteras, Gemma Salvadó, Mahnaz Shekari, Marc Vilanova.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

JLM has served/serves as a consultant or at advisory boards for the following for-profit companies, or has given lectures in symposia sponsored by the following for-profit companies: Roche Diagnostics, Genentech, Novartis, Lundbeck, Oryzon, Biogen, Lilly, Janssen, Green Valley, MSD, Eisai, Alector, BioCross, GE Healthcare, ProMIS Neurosciences, NovoNordisk, Zambón, Cytox and Nutricia. The rest of the authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

The complete list of collaborators of the ALFA Study can be found in the Acknowledgements.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Natalia Vilor-Tejedor, Email: natalia.vilortejedor@crg.eu.

Juan Domingo Gispert, Email: jdgispert@barcelonabeta.org.

References

- Aas M, Haukvik UK, Djurovic S, Tesli M, Athanasiu L, Bjella T, Hansson L, et al. Interplay between childhood trauma and bdnf val66met variants on blood bdnf mrna levels and on hippocampus subfields volumes in schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;59:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaike H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. Springer NY. 1998 doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-1694-0_15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez A, Aleixandre M, Linares C, Masliah E, Moessler H. Apathy and APOE4 are associated with reduced BDNF levels in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2014;42(4):1347–1355. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autry AE, Monteggia LM. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64(2):238–258. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathina S, Das UN. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its clinical implications. Arch Med Sci AMS. 2015;11(6):1164–1178. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.56342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauwendraat C, Faghri F, Pihlstrom L, Geiger JT, Elbaz A, Lesage S, Corvol J-C, et al. NeuroChip, an updated version of the NeuroX genotyping platform to rapidly screen for variants associated with neurological diseases. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;57:247.e9–247.e13. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROBIOLAGING.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blesa R, Pujol M, Aguilar M, Santacruz P, Bertran-Serra I, Hernández G, Sol JM, et al. Clinical validity of the ‘mini-mental state’ for spanish speaking communities. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39(11):1150–1157. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3932(01)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhm P, Peña-Casanova J, Gramunt N, Manero RM, Terrón C, Quiñones-Ubeda S (2005) Versión española del Memory Impairment Screen (MIS): datos normativos y de validez discriminativa [Spanish version of the Memory Impairment Screen (MIS): normative data and discriminant validity]. Neurologia 20(8):402-411 [PubMed]

- Boots EA, Schultz SA, Clark LR, Racine AM, Darst BF, Koscik RL, Carlsson CM, et al. BDNF Val66Met predicts cognitive decline in the wisconsin registry for Alzheimer’s prevention. Neurology. 2017;88(22):2098–2106. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschke H, Kuslansky G, Katz M, Stewart WF, Sliwinski MJ, Eckholdt HM, Lipton RB. Screening for dementia with the memory impairment screen. Neurology. 1999;52(2):231–238. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschke H, Mowrey WB, Ramratan WS et al (2017) Memory binding test distinguishes amnestic mild cognitive impairment and dementia from cognitively normal elderly [published correction appears in Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2017 Dec 1;32(8):1037-1038]. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 32(1):29-39. 10.1093/arclin/acw083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cacciaglia R, Molinuevo JL, Falcón C, Brugulat-Serrat A, Sánchez-Benavides G, Gramunt N, Esteller M, et al. Effects of APOE -Ε4 allele load on brain morphology in a cohort of middle-aged healthy individuals with enriched genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14(7):902–912. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciaglia R, Molinuevo JL, Sánchez-Benavides G, Falcón C, Gramunt N, Brugulat-Serrat A, Grau O, Gispert J, ALFA Study Episodic memory and executive functions in cognitively healthy individuals display distinct neuroanatomical correlates which are differentially modulated by aging. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39(11):4565–4579. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Bo, Bauer IE, Sharma AN, Mwangi B, Frazier T, Lavagnino L, Zunta-Soares GB, et al. Reduced hippocampus volume and memory performance in bipolar disorder patients carrying the BDNF Val66met met allele. J Affect Disord. 2016;198(July):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Flores R, La Joie R, Chételat G. Structural imaging of hippocampal subfields in healthy aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2015;309:29–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan MF, Kojima M, Callicott JH, et al. The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function. Cell. 2003;112(2):257–269. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge LL, Engel SA, Zeineh MM, Bookheimer SY, Knowlton BJ. A dissociation of encoding and retrieval processes in the human hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2005;25(13):3280–3286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3420-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elman JA, Panizzon MS, Gillespie NA, Hagler DJ, Fennema-Notestine C, Eyler LT, McEvoy LK, et al. Genetic architecture of hippocampal subfields on standard resolution MRI: how the parts relate to the whole. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40(5):1528–1540. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erten-Lyons D, Woltjer RL, Dodge H, Nixon R, Vorobik R, Calvert JF, Leahy M, Montine T, Kaye J. Factors associated with resistance to dementia despite high Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2009;72(4):354–360. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000341273.18141.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati A, Zimmerman ME, Katz MJ, Sundermann EE, Smith JL, Lipton ML, Lipton RB. Hippocampal subfields differentially correlate with chronic pain in older adults. Brain Res. 2014;1573:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzmeier N, Ren J, Damm A, Monté-Rubio G, Boada M, Ruiz A, Ramirez A, et al. The BDNFVal66Met SNP modulates the association between beta-amyloid and hippocampal disconnection in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0404-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frodl T, Skokauskas N, Frey E-M, Morris D, Gill M, Carballedo A. BDNFVal66Met genotype interacts with childhood adversity and influences the formation of hippocampal subfields. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(12):5776–5783. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaye A, Davis SK. Genetic model misspecification in genetic association studies. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):569. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2911-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomar JJ, Conejero-Goldberg C, Huey ED, Davies P, Goldberg TE. Lack of neural compensatory mechanisms of bdnf val66met met carriers and APOE E4 carriers in healthy aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;39:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Goldberg TE, Mattay VS, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met polymorphism affects human memory-related hippocampal activity and predicts memory performance. J Neurosci. 2003;23(17):6690–6694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06690.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrisberger F, Spalek K, Smieskova R, Schmidt A, Coynel D, Milnik A, Fastenrath M, et al. The association of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and the hippocampal volumes in healthy humans: a joint meta-analysis of published and new data. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;42:267–278. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrisberger F, Smieskova R, Schmidt A, Lenz C, Walter A, Wittfeld K, Grabe HJ, Lang UE, Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S. BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and hippocampal volume in neuropsychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;55:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hett K, Ta VT, Catheline G, Tourdias T, Manjon J, Coupe P. Multimodal hippocampal subfield grading for Alzheimer’s disease classification. BioRxiv. 2018 doi: 10.1101/293126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hibar DP, Adams HHH, Jahanshad N, Chauhan G, Stein JL, Hofer E, Renteria ME, et al. Novel genetic loci associated with hippocampal volume. Nat Commun. 2017;8:13624. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias JE, Augustinack JC, Nguyen K, Player CM, Player A, Wright M, Roy N, et al. A computational atlas of the hippocampal formation using Ex Vivo, ultra-high resolution MRI: application to adaptive segmentation of in vivo MRI. NeuroImage. 2015;115:117–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen WJ, Ossenkoppele R, Knol DL, Tijms BM, Scheltens P, Verhey FRJ, Visser PJ, et al. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid pathology in persons without dementia. JAMA. 2015;313(19):1924. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin K, Peel AL, Mao XO, Xie L, Cottrell BA, Henshall DC, Greenberg DA. Increased hippocampal neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(1):343–347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2634794100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerchner GA, Berdnik D, Shen JC, Bernstein JD, Fenesy MC, Deutsch GK, Wyss-Coray T, Rutt BK. APOE Ε4 worsens hippocampal CA1 apical neuropil atrophy and episodic memory. Neurology. 2014;82(8):691–697. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowiański P, Lietzau G, Czuba E, Waśkow M, Steliga A, Moryś J. BDNF: a key factor with multipotent impact on brain signaling and synaptic plasticity. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2018;38(3):579–593. doi: 10.1007/s10571-017-0510-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YY, Villemagne VL, Laws SM, Ames D, Pietrzak RH, Ellis KA, Harrington KD, et al. BDNF Val66Met, Aβ amyloid, and cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(11):2457–2464. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YY, Villemagne VL, Laws SM, Pietrzak RH, Snyder PJ, Ames D, Ellis KA, et al. APOE and BDNF polymorphisms moderate amyloid β-related cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(11):1322–1328. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y-H, Jiao S-S, Wang Y-R, Xian-Le Bu, Yao X-Q, Xiang Y, Wang Q-H, et al. Associations between ApoEε4 carrier status and serum BDNF levels—new insights into the molecular mechanism of ApoEε4 actions in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;51(3):1271–1277. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8804-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Yu J-T, Wang H-F, Han P-R, Tan C-C, Wang C, Meng X-F, Risacher SL, Saykin AJ, Tan L. APOE genotype and neuroimaging markers of Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86(2):127–134. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-307719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Shi J, Gutman BA, Baxter LC, Thompson PM, Caselli RJ, Wang Y, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Influence of APOE genotype on hippocampal atrophy over time - an N=1925 surface-based ADNI study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0152901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinuevo JL, Gramunt N, Gispert JD, Fauria K, Esteller M, Minguillon C, Sánchez-Benavides G, et al. The ALFA project: a research platform to identify early pathophysiological features of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement Translat Res Clin Inter. 2016;2(2):82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (Cdr): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller SG, Weiner MW. Selective effect of Age, Apo E4, and Alzheimer’s disease on hippocampal subfields. Hippocampus. 2009;19(6):558–564. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller SG, Schuff N, Yaffe K, Madison C, Miller B, Weiner MW. Hippocampal atrophy patterns in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31(9):1339–1347. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller SG, Yushkevich PA, Das S, Wang L, Van Leemput K, Iglesias JE, Alpert K, et al. Systematic comparison of different techniques to measure hippocampal subfield volumes in ADNI2. NeuroImag Clin. 2018;17:1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notaras M, van den Buuse M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (bdnf): novel insights into regulation and genetic variation. Neurosci. 2018 doi: 10.1177/1073858418810142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numakawa T, Odaka H, Adachi N. Actions of brain-derived neurotrophin factor in the neurogenesis and neuronal function, and its involvement in the pathophysiology of brain diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(11):3650. doi: 10.3390/ijms19113650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Casanova J, Quiñones-Ubeda S, Gramunt-Fombuena N, Quintana-Aparicio M, Aguilar M, Badenes D, Cerulla N, et al. Spanish multicenter normative studies (NEURONORMA Project): norms for verbal fluency tests. Arch Clin Neuropsychol Off J Nat Acad Neuropsychol. 2009;24(4):395–411. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acp042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pievani M, Galluzzi S, Thompson PM, Rasser PE, Bonetti M, Frisoni GB. APOE4 is associated with greater atrophy of the hippocampal formation in Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage. 2011;55(3):909–919. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlack ST, Meyer P, Cacciaglia R, Liebscher C, Ridder S, Flor H. Bigger is better! Hippocampal volume and declarative memory performance in healthy young men. Brain Struc Func. 2014;219(1):255–267. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0497-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, Maller J, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinones-Ubeda S (2009) Desenvolupament, normalització i validació de la versió estandard de la segona versió del Test Barcelona. Ramon Llull University, Barcelona

- Radmanesh F, Devan WJ, Anderson CD, Rosand J, Falcone GJ, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) Accuracy of imputation to infer unobserved APOE epsilon alleles in genome-wide genotyping data. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(10):1239–1242. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramier AM, Hecaen H. Role respectif des atteintes frontales et de la lateralisation lesionnelle dans les deficits de la “fluence verbale”. Rev Neurol. 1970;123:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman EM, Chen K, Liu X, Bandy D, Meixiang Yu, Lee W, Ayutyanont N, et al. fibrillar amyloid-beta burden in cognitively normal people at 3 levels of genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(16):6820–6825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900345106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart V, Bove SE, Volfson D, Lewis DA, Kleiman RJ, Lanz TA. Evaluation of TrkB and BDNF transcripts in prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum from subjects with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;77:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckman K, Williams SM. Calculation and use of the Hardy-Weinberg model in association studies. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0118s57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A, Nelson TJ, Alkon DL. ApoE4 and A oligomers reduce bdnf expression via HDAC nuclear translocation. J Neurosci. 2015;35(19):7538–7551. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0260-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Leporé N, Gutman BA, Thompson PM, Baxter LC, Caselli RJ, Wang Y, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Genetic influence of apolipoprotein E4 genotype on hippocampal morphometry: an N = 725 surface-based Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(8):3903–3918. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs MJ, Thompson CS, Moreau D, McNair NA, Wu CC, Lamb YN, Mckay NS, et al. Human sensory long-term potentiation (LTP) predicts visual memory performance and is modulated by the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val66Met polymorphism. BioRxiv. 2018 doi: 10.1101/284315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suthana NA, Donix M, Wozny DR, Bazih A, Jones M, Heidemann RM, Trampel R, et al. High-Resolution 7T FMRI of human hippocampal subfields during associative learning. J Cognit Neurosci. 2015;27(6):1194–1206. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh YL, Ng T, Tan M, Tan A, Chan A. Impact of brain-derived neurotrophic factor genetic polymorphism on cognition: a systematic review. Brain Behav. 2018;8(7):e01009. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai S-J. Critical Issues in BDNF Val66Met genetic studies of neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer D, Rokicki J, Kaufmann T, Córdova-Palomera A, Moberget T, Alnæs D, Bettella F, et al. Brain scans from 21,297 individuals reveal the genetic architecture of hippocampal subfield volumes. Mol Psychiatry. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0262-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Petten C. Relationship between hippocampal volume and memory ability in healthy individuals across the lifespan: review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42(10):1394–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilar M, Mira H. Regulation of neurogenesis by neurotrophins during adulthood: expected and unexpected roles. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:26. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward DD, Summers MJ, Saunders NL, Janssen P, Stuart KE, Vickers JC. APOE and BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms combine to influence episodic memory function in older adults. Behav Brain Res. 2014;271:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, Coleman PD, Flood DG, Troncoso JC. Differences in the pattern of hippocampal neuronal loss in normal ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1994;344(8925):769–772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL. The protective role of brain size in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(12):1799–1801. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisse LEM, Biessels GJ, Geerlings MI. A critical appraisal of the hippocampal subfield segmentation package in freesurfer. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:261. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeni CP, Mwangi B, Cao Bo, Hasan KM, Walss-Bass C, Zunta-Soares G, Soares JC. Interaction between BDNF rs6265 met allele and low family cohesion is associated with smaller left hippocampal volume in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2016;189:94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 (PDF 13 kb)Figure S1. Heatmap showing pair correlations across brain structures of ALFA project subsample, with blue color indicating positive correlations and red colour indicating negative correlations. Legend: CA1, cornu ammonis region 1; CA23, cornu ammonis region 23; CA4, cornu ammonis region 4; GC-ML-DG, granule cells in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus; hata, hippocampal-amygdaloid transition region; HP, hippocampus.

Supplementary file2 (PDF 257 kb) Figure S2. Differences according BDNF Val66Met genotypes in associations between APOE-ε4 and the remaining subfields. Legend: CA1, cornu ammonis region 1; CA23, cornu ammonis region 23; hata, hippocampal-amygdaloid transition region.

Supplementary file3 (DOCX 21 kb) Table S1. Main effects of Val66Met genotype on hippocampal subfields (mm3). All models were adjusted by sex, years of education, number of APOE-e4 allele and total intracranial volume.

Supplementary file4 (DOCX 14 kb) Table S2. Main effects of number of APOE-e4 alleles on hippocampal subfields (mm3). All models were adjusted by sex, years of education, age, val66Met genotypes and total intracranial volume.