Abstract

Background

Preterm birth is the leading cause of child mortality globally, with many survivors experiencing long-term adverse consequences. Preliminary evidence suggests that numbers of preterm births greatly reduced following implementation of policy measures aimed at mitigating the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. We aimed to study the impact of the COVID-19 mitigation measures implemented in the Netherlands in a stepwise fashion on March 9, March 15, and March 23, 2020, on the incidence of preterm birth.

Methods

We used a national quasi-experimental difference-in-regression-discontinuity approach. We used data from the neonatal dried blood spot screening programme (2010–20) cross-validated against national perinatal registry data. Stratified analyses were done according to gestational age subgroups, and sensitivity analyses were done to assess robustness of the findings. We explored potential effect modification by neighbourhood socioeconomic status, sex, and small-for-gestational-age status.

Findings

Data on 1 599 547 singleton neonates were available, including 56 720 births that occurred after implementation of COVID-19 mitigation measures on March 9, 2020. Consistent reductions in the incidence of preterm birth were seen across various time windows surrounding March 9 (± 2 months [n=531 823] odds ratio [OR] 0·77, 95% CI 0·66–0·91, p=0·0026; ± 3 months [n=796 531] OR 0·85, 0·73–0·98, p=0·028; ± 4 months [n=1 066 872] OR 0·84, 0·73–0·97, p=0·023). Decreases in incidence observed following the March 15 measures were of smaller magnitude, but not statistically significant. No changes were observed after March 23. Reductions in the incidence of preterm births after March 9 were consistent across gestational age strata and robust in sensitivity analyses. They appeared confined to neighbourhoods of high socioeconomic status, but effect modification was not statistically significant.

Interpretation

In this national quasi-experimental study, initial implementation of COVID-19 mitigation measures was associated with a substantial reduction in the incidence of preterm births in the following months, in agreement with preliminary observations elsewhere. Integration of comparable data from across the globe is needed to further substantiate these findings and start exploring underlying mechanisms.

Funding

None.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and the measures taken to prevent the spread of infection and mitigate its population health effects are having an unprecedented impact on society. The sudden occurrence of the pandemic and the scale and immediacy of the policy responses taken provide a unique opportunity to evaluate their effects as a natural experiment.1 Reports from Denmark2 and Ireland3 independently provided evidence indicating substantial reductions in the number of extremely preterm and very-low-birthweight births following national COVID-19 mitigation measures. Several potential underlying mechanisms have been proposed, including improvements in ambient air quality and reductions in maternal stress and incidence of infections.3

The first recognised COVID-19 case in the Netherlands was confirmed in Noord-Brabant, one of twelve Dutch provinces, on Feb 27, 2020.4 The first COVID-19-related death occurred on March 6, and from that day, people living in Noord-Brabant were advised to stay indoors if they had possible COVID-19 symptoms. On separate occasions between March 9 and March 23, several national measures were then taken and widely communicated in an attempt to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands (panel ; appendix p 1).5, 6, 7, 8

Panel. Timeline of implementation of key COVID-19 mitigation measures in the Netherlands.

March 9, 2020

-

•

Advice against handshaking and for using paper handkerchiefs, sneezing or coughing in one's elbow, and regular handwashing

-

•

Advice for staying at home when experiencing cold symptoms or fever or when having been in contact with COVID-19-positive person or having visited a high-risk area

March 12, 2020

-

•

Advice against social interaction and visiting older people

-

•

Events of more than 100 individuals are cancelled

-

•

People need to work from home whenever possible

-

•

People need to stay home if symptomatic (fever, respiratory complaints)

March 15, 2020

-

•

Closing down of schools and childcare facilities

-

•

Closing down of hospitality industry and of non-essential services involving physical contact

-

•

Physical distancing introduced (1·5-m rule)

March 23, 2020

-

•

All events and gatherings cancelled

-

•

No groups of larger than three people allowed in public areas (exceptions for households and children)

-

•

Issuing of fines for not complying with physical distancing

-

•

Municipalities can close down busy places and shops

Globally, more than one in ten babies are born preterm, and preterm birth is the primary contributor to mortality in early life.9 Additionally, preterm birth survivors and their families frequently experience long-term adverse consequences.10, 11, 12, 13 Very few cases of preterm birth can be prevented using currently available strategies.14 As such, exploration of the possible link between national lockdown measures and a decrease in preterm births is needed, and if confirmed, so is identification of the underlying mechanisms to inform and optimise future approaches to prevent preterm birth from devastating families' lives.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Preliminary evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic and the measures taken by governments to mitigate its impact on population health were followed by reductions in preterm births, particularly those occurring at very low gestational ages. We searched the MEDLINE, medRxiv, and Lancet preprint online databases for reports published between database inception and July 25, 2020, in any language that studied this association using the following search terms: (coronavirus OR COVID OR SARS-COV-2 OR lockdown) AND (preterm OR premature OR low birth weight OR low birthweight). We identified two relevant uncontrolled before-after studies. One used data from the Danish National Screening Biobank, and a single-centre study from Ireland used hospital records. In Denmark, data from 31 180 singleton births between March 12 and April 14 in the years 2015–20 were analysed. A reduction in births occurring before 28 weeks gestation from 2·19 per 1000 births to 0·19 per 1000 births was identified in the 2020 cohort versus the 2015–19 cohorts (p<0·001). Among 30 705 births in the University Maternity Hospital Limerick in Ireland, the proportion of babies with very low birthweight (ie, <1500 grams; used as a proxy for preterm birth) dropped from 8·18 per 1000 in the years 2001–2019 to 2·17 per 1000 in 2020 (p=0·022). None of the 1381 babies born in 2020 had a birthweight of less than 1000 grams, whereas an average of 3·0 per 1000 did before 2020. An additional single-centre study from London (UK) explored pregnancy outcomes between 1681 births occurring before and 1718 births after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (rather than start of the mitigation measures). An increase in stillbirths from 1·2 per 1000 births to 7·0 per 1000 births was noted (p=0·01), with no significant change in preterm births.

Added value of this study

The potential association between COVID-19 mitigation measures and a reduction in extremely preterm and very-low-birthweight births, as reported in the Danish and Irish studies, has gained substantial attention. The studies reported thus far have however had relatively small sample sizes (up to 5162 post-implementation births) and a short post-implementation observational period. The uncontrolled before-after design used also restricts causal interpretation. We addressed these limitations by applying a quasi-experimental difference-in-regression-discontinuity design to assess the impact of the COVID-19 mitigation measures on the incidence of preterm birth in the Netherlands. Using a dataset of more than 1·5 million singleton births, including 56 720 post-implementation births, we found consistent reductions in preterm births across various time windows surrounding the March 9, 2020, implementation of the first set of COVID-19 mitigation measures. Extension of the measures on March 15 and 23 had no demonstrable effect on preterm birth incidence.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our study confirms evidence from earlier preliminary studies indicating that substantial reductions in preterm births occurred following national introduction of COVID-19 mitigation measures. International collaborative efforts are needed to collate evidence from across the globe to further substantiate these findings and to study the underlying mechanisms. Such efforts could help uncover new opportunities for preterm birth prevention with substantial effects on global perinatal and public health.

Although the link between COVID-19 mitigation measures and reductions in the incidence of preterm birth identified in the aforementioned Danish and Irish studies has sparked substantial optimism globally regarding its potential to help identify new clues for effective prevention, the evidence base is still small.2, 3 Both studies had relatively small sample sizes and the methods used restrict causal interpretation.2, 3 We, therefore, aimed to use a much larger sample, consisting of routinely collected data, and a quasi-experimental approach to study the impact of the COVID-19 mitigation measures implemented in the Netherlands on the incidence of preterm birth.

Methods

Study design and participants

We did a difference-in-regression-discontinuity analysis to investigate the association between the national implementation of COVID-19 mitigation measures and the incidence of preterm birth in the Netherlands.

According to national guidelines,15 women with uncomplicated pregnancies are offered at least 6–9 antenatal visits, the first one ideally occurring before the tenth week of gestation. At this visit, crown-rump length is measured to estimate gestational age. All women are offered a fetal anomaly scan at around 20 weeks gestation. In 2018, 8% of primiparous women and 23% of multiparous women had a planned home delivery.16

We obtained data on all singleton babies who had undergone neonatal blood spot screening in the Netherlands between Oct 9, 2010, and, the most recent data available at the time of extraction, July 16, 2020. The study period was set to include 10 years and 5 months before implementation of the first national COVID-19 mitigation measures (March 9, 2020; panel). Data were provided by the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment as extracted from Praeventis.17 Praeventis is a national database containing data from all babies that have undergone neonatal blood spot screening. In the national screening programme, neonates are screened for a range of diseases after 72 h of life. Screening can take place in the hospital or at home. According to national guidelines, there is no need to delay screening for neonates born preterm or on parenteral feeding.18 In 2018, 37% of neonates were screened within 96 h of birth, and 99% within the first week of life.19 On the neonatal dried blood spot card, health professionals record several maternal and neonatal characteristics.20

Multiple births were excluded from the analysis due to the inherent increased risk of preterm birth. Multiple records registered with identical surnames, birth dates, and postcode indicated multiple births. We also excluded babies whose registered gestational age was less than 24 weeks and 0 days or more than 41 weeks and 6 days. Dutch national multidisciplinary guidelines advise against active management of babies born at gestational ages of less than 24 weeks and 0 days.21

For validation purposes, characteristics of our cohort were cross-referenced at aggregate level against data from Perined for selected years. Perined is the national linked pregnancy and birth registry and is based on data provided by midwifery, general practice, and obstetric and paediatric practices.16 Perined data are typically made available 1–2 years after initial registration of pregnancies and births, invalidating the use of Perined data to address our primary research question.

According to Dutch law (Wet medisch-wetenschappelijk onderzoek met mensen) no formal ethical review was required. According to standard procedures and under strict conditions that were fulfilled, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment allows anonymised data registered as part of the screening programme to be used for research purposes with waiver of consent.22 A protocol for the study was developed a priori and approved by National Institute for Public Health and the Environment before data provision.

Procedures

The following individual-level data were extracted from Praeventis: calendar week of birth, gestational age (in days), birthweight (in grams), sex, and four-digit postcode. Four-digit postcode identifies areas with an average of 2160 households and was used to derive province of residence, neighbourhood socioeconomic status, and level of neighbourhood urbanisation. Neighbourhood socioeconomic status scores are calculated by the Netherlands Institute for Social Research and were available for 2010, 2014, 2016, and 2017.23 Socioeconomic status scores are based on mean household income, proportion of population with low income, proportion of population with low educational level, and proportion of population without paid work. Urbanisation was dichotomised, with urban areas defined as those with more than 2500 residential addresses per km2. Individual-level sex-specific and gestational age-specific birthweight centiles were calculated using national reference curves.24

Statistical analysis

Two earlier studies2, 3 have identified a link between national implementation of COVID-19 mitigation measures and a reduction in extremely preterm and very-low-birthweight births. In these studies, data on post-implementation births were available for 51622 and 1381 births.3 The Netherlands has around 170 000 births annually, which translates into around 60 000 births after implementation of mitigation measures, including around 4000 preterm births. Given the positive findings in earlier studies,2, 3 which had much smaller sample sizes, we anticipated that our dataset would provide ample statistical power to identify an association of similar magnitude between the COVID-19 mitigation measures and preterm births in the Netherlands.

We tabulated characteristics of the study population according to the periods from which they were derived. We furthermore tabulated selected characteristics against published Perined annual reports, available up to 2018.16

We studied the association between national implementation of the COVID-19 mitigation measures and the incidence of preterm births using a difference-in-regression-discontinuity approach.25, 26 This quasi-experimental technique can be used when the exposure of interest is assigned by the value of a continuously measured random variable and whether that variable lies above (or below) some cutoff value. In this study, calendar week of birth is the assignment variable, and the cutoff corresponds to the implementation dates of COVID-19 mitigation measures. Quasi-experimental techniques provide a robust alternative to experimentation when randomised assignment is not possible and facilitate causal inference over purely observational approaches.27 We did separate analyses for COVID-19 mitigation measures implemented on March 9, March 15, and March 23 (panel). A separate analysis was not possible for measures implemented on March 12, because of the temporal granularity of the individual-level data (ie, weekly rather than daily). We a-priori hypothesised that any reductions in preterm birth would most likely have followed the measures implemented on March 15, because these were considered to be most comprehensive. We assessed four time windows in separate analyses: 1 month, 2 months, 3 months, and 4 months before and after dates of implementation. Use of these relatively short time windows allowed us to exclude other interventions or major influences and assume that any change observed was due to the COVID-19 mitigation measures. The analyses accounted for underlying temporal trends,28 seasonal variation, and potential other time-variant factors affecting preterm birth incidence by comparing the period surrounding implementation of the measures in 2020 to the exact same time periods in each year preceding the COVID-19 pandemic (2010–19). By following this approach there was no need to adjust for individual-level variables in the analysis.

The assumptions and conditions for a valid regression discontinuity were met; the cutoff value (March 9, 15, or 23, 2020) and decision rule (exposed or unexposed to COVID-19 mitigation measures) were known, the assignment variable (week of birth) is continuous around the cutoff and not affected by the lockdown (appendix p 2), the outcomes are continuous at the threshold and are observed for all pregnancies, and graphical analysis shows a discontinuity around the threshold, suggesting an intervention effect (appendix pp 3–14).

In the primary analyses, the outcome of interest was the overall incidence of preterm birth (ie, number of babies born at a gestational age of <37 weeks and 0 days per 1000 babies that underwent neonatal blood spot screening). In additional stratified analyses, we assessed whether there were differential changes in preterm birth incidence following the COVID-19 mitigation measures according to the degree of prematurity: 24 weeks and 0 days to 25 weeks and 6 days, 26 weeks and 0 days to 27 weeks and 6 days, 28 weeks and 0 days to 31 weeks and 6 days, and 32 weeks and 0 days to 36 weeks and 6 days.

Substantial evidence indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic and the measures taken to mitigate its impact differentially affect socioeconomic groups.29, 30 To assess possible variation in impact of the Dutch COVID-19 mitigation measures according to socioeconomic status, we tested for effect modification by neighbourhood socioeconomic status. In additional post-hoc analyses we explored potential effect modification by small-for-gestational-age status and neonatal sex.

Some mechanisms potentially underlying a link between the COVID-19 mitigation measures and preterm birth might not have an immediate effect. However, population anticipatory effects might already have changed their behaviour before formal implementation of COVID-19 mitigation measures. We therefore did two sets of sensitivity analyses introducing a period of censoring of data, thus excluding data from the first week and from the first two weeks directly before and directly following introduction of the measures.

Analyses were done using R version 4.0.2.

Role of the funding source

There was no funding source for this study. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

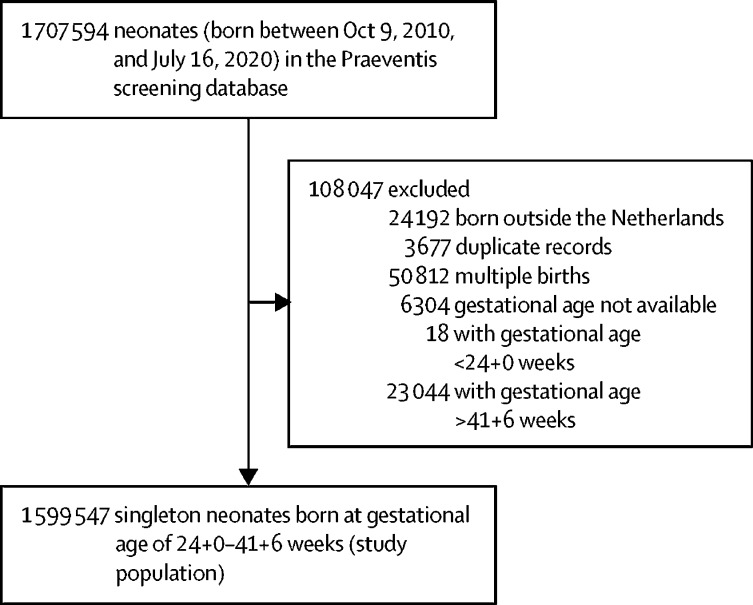

1 707 594 records were available in the Praeventis neonatal screening database for the study period. 1 599 547 singleton neonates were included in our analysis (figure 1 ). Characteristics of this population are shown in table 1 . Cross-validation against Perined data for selected years (2011, 2014, and 2017) showed that babies born at the lowest gestational ages and those with the lowest birthweights were consistently underrepresented in our cohort throughout the study period (appendix p 15).

Figure 1.

Study profile

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Value | ||

|---|---|---|

| Term birth | 1 515 338 (94·8%) | |

| Preterm birth | 84 209 (5·2%) | |

| 32 weeks and 0 days to 36 weeks and 6 days | 72 753 (4·5%) | |

| 28 weeks and 0 days to 31 weeks and 6 days | 8248 (0·5%) | |

| 26 weeks and 0 days to 27 weeks and 6 days | 2114 (0·1%) | |

| 24 weeks and 0 days to 25 weeks and 6 days | 1094 (0·1%) | |

| Gestational age, weeks | 39·5 (1·7) | |

| Birthweight, grams* | 3436 (547) | |

| Birthweight centile* | 49·3 (29·3) | |

| Small for gestational age* | 171 910 (10·7%) | |

| Sex† | ||

| Male | 819 886 (51·2%) | |

| Female | 779 654 (48·8%) | |

| Province of residence‡ | ||

| Drenthe | 39 344 (2·5%) | |

| Flevoland | 45 072 (2·8%) | |

| Friesland | 57 112 (3·6%) | |

| Gelderland | 181 830 (11·4%) | |

| Groningen | 49 643 (3·1%) | |

| Limburg | 82 613 (5·2%) | |

| Noord-Brabant | 221 212 (13·8%) | |

| Noord-Holland | 273 616 (17·1%) | |

| Overijssel | 109 762 (6·9%) | |

| Utrecht | 137 630 (8·6%) | |

| Zeeland | 31 278 (1·9%) | |

| Zuid-Holland | 369 084 (23·1%) | |

| Living in urban area‡ | 590 028 (36·9%) | |

| Neighbourhood socioeconomic status§ | ||

| Low (<20th percentile) | 301 611 (18·8%) | |

| Medium (20th–80th percentile) | 970 522 (60·7%) | |

| High (>80th percentile) | 319 809 (20·0%) | |

Data are n (%) or mean (SD).

Birthweight was missing for 391 individuals (0·02%).

Sex was unspecified for fewer than 10 individuals. According to National Institute for Public Health and the Environment policy, cells containing fewer than 10 individuals are censored.

Postcode was missing for 1195 individuals (0·07%).

7605 cases (0·5%) could not be assigned to a Netherlands Institute for Social Research socioeconomic status category: 1195 due to missing postcode and 6410 because the Netherlands Institute for Social Research does not calculate neighbourhood socioeconomic status scores for postcodes with fewer than 100 households.

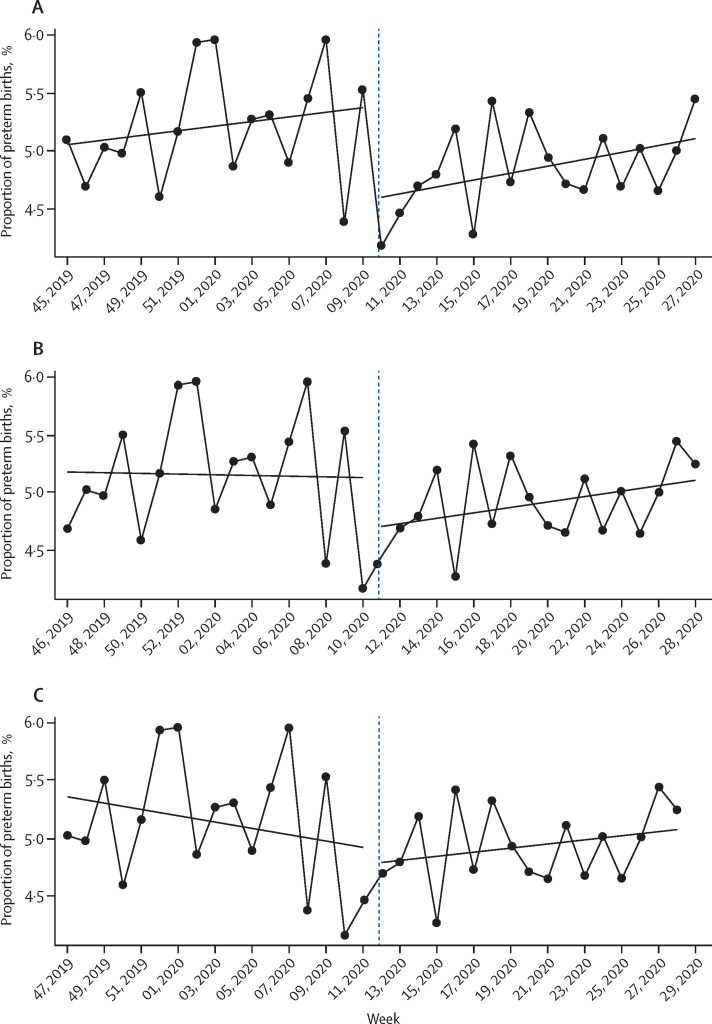

A clear discontinuity in the regression lines was observed for the initial set of COVID-19 mitigation measures introduced on March 9, 2020 (figure 2 ; appendix pp 3–14). Accordingly, implementation of the March 9 measures was consistently associated with substantial reductions in preterm birth in the 2-month, 3-month, and 4-month time windows surrounding implementation (± 2 months [n=531 823] odds ratio [OR] 0·77, 95% CI 0·66–0·91, p=0·0026; ± 3 months [n=796 531] OR 0·85, 0·73–0·98, p=0·028; ± 4 months [n=1 066 872] OR 0·84, 0·73–0·97, p=0·023; table 2 ). These reductions in preterm births were apparent across gestational age strata, but were statistically significant only in the 32 weeks and 0 days to 36 weeks and 6 days subgroup (table 2). No significant change in preterm birth was observed for measures implemented on March 15 and 23 (table 2).

Figure 2.

Regression discontinuity in weekly preterm birth incidence surrounding implementation of COVID-19 mitigation measures

Weekly percentage of preterm births for March 9 (A), March 15 (B), and March 23 (C), 2020, cutoffs.

Table 2.

Impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on the incidence of preterm birth by time window

| ±1 month | ±2 months | ±3 months | ±4 months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures introduced on March 9, 2020 | |||||

| n | 262 600 | 531 823 | 796 531 | 1 066 872 | |

| Preterm birth | 0·91 (0·68–1·20) | 0·77 (0·66–0·91) | 0·85 (0·73–0·98) | 0·84 (0·73–0·97) | |

| 32 weeks and 0 days to 36 weeks and 6 days | 0·91 (0·67–1·23) | 0·78 (0·66–0·94) | 0·85 (0·72–0·99) | 0·83 (0·71–0·97) | |

| 28 weeks and 0 days to 31 weeks and 6 days | 0·80 (0·34–1·89) | 0·78 (0·46–1·33) | 0·88 (0·55–1·40) | 0·91 (0·58–1·42) | |

| 26 weeks and 0 days to 27 weeks and 6 days | 1·57 (0·20–12·00) | 0·66 (0·21–2·05) | 0·82 (0·30–2·21) | 0·99 (0·38–2·55) | |

| 24 weeks and 0 days to 25 weeks and 6 days | 0·89 (0·10–13·00) | 0·48 (0·13–1·76) | 0·90 (0·29–2·81) | 1·00 (0·33–3·04) | |

| Measures introduced on March 15, 2020 | |||||

| n | 259 825 | 528 464 | 797 799 | 1 065 261 | |

| Preterm birth | 1·17 (0·91–1·49) | 0·96 (0·81–1·13) | 0·97 (0·84–1·13) | 0·96 (0·83–1·10) | |

| 32 weeks and 0 days to 36 weeks and 6 days | 1·11 (0·58–1·45) | 0·95 (0·79–1·13) | 0·95 (0·82–1·11) | 0·92 (0·80–1·07) | |

| 28 weeks and 0 days to 31 weeks and 6 days | 1·30 (0·48–2·23) | 0·88 (0·51–1·50) | 0·96 (0·61–1·51) | 1·00 (0·65–1·55) | |

| 26 weeks and 0 days to 27 weeks and 6 days | 4·96 (0·68–36·05) | 1·33 (0·41–4·28) | 1·37 (0·50–3·69) | 1·60 (0·62–4·13) | |

| 24 weeks and 0 days to 25 weeks and 6 days | 7·83 (0·73–83·47) | 1·89 (0·48–7·29) | 2·03 (0·63–6·50) | 2·15 (0·69–6·68) | |

| Measures introduced on March 23, 2020 | |||||

| n | 263 098 | 531 720 | 799 511 | 1 067 665 | |

| Preterm birth | 1·27 (0·99–1·60) | 1·06 (0·89–1·25) | 1·05 (0·91–1·22) | 1·03 (0·90–1·18) | |

| 32 weeks and 0 days to 36 weeks and 6 days | 1·27 (0·99–1·64) | 1·07 (0·90–1·28) | 1·05 (0·90–1·22) | 1·01 (0·87–1·17) | |

| 28 weeks and 0 days to 31 weeks and 6 days | 1·18 (0·56–2·48) | 0·98 (0·57–1·67) | 1·08 (0·69–1·69) | 1·12 (0·73–1·72) | |

| 26 weeks and 0 days to 27 weeks and 6 days | 1·26 (0·22–7·09) | 0·89 (0·28–2·83) | 1·10 (0·42–2·87) | 1·33 (0·54–3·29) | |

| 24 weeks and 0 days to 25 weeks and 6 days | 0·45 (0·07–3·06) | 0·92 (0·26–3·26) | 1·22 (0·42–3·55) | 1·31 (0·46–3·68) | |

Odds ratios (95% CI) indicating odds of preterm birth across various time windows directly following implementation of the COVID-19 mitigation measures versus the odds of preterm birth in similar time windows directly preceding the measures. Estimates derived from difference-in-regression-discontinuity analysis accounting for temporal preterm birth patterns across the same time windows in previous years (2010–2019).

Given these findings and to reduce the number of analyses, we explored effect modification and did sensitivity analyses only for the March 9 COVID-19 mitigation measures, and only for the overall incidence of preterm birth. Although the reductions in preterm birth predominantly occurred in populations living in high-socioeconomic-status neighbourhoods, effect modification by socioeconomic status was not statistically significant (appendix p 16). No statistically significant effect modification by small-for-gestational-age status or sex was seen (appendix pp 17–18). Sensitivity analyses, in which birth data from 1 or 2 weeks surrounding implementation of the March 9 measures were censored, generally confirmed the findings of the primary analyses, although several outcomes for 3 or 4 months before and after implementation were no longer statistically significant (appendix p 19).

Discussion

In this large national quasi-experimental study spanning a 10-year period, substantial reductions in preterm births were observed following implementation of the first national COVID-19 mitigation measures in the Netherlands. These reductions were consistent across various degrees of prematurity. Extension of the COVID-19 measures introduced 1 week and 2 weeks later had no significant effect on preterm births. Taken together with preliminary evidence from other countries,2, 3 these findings provide opportunities to identify novel preventive strategies for preterm birth.

To our knowledge, our study is by far the largest to have assessed the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on the incidence of preterm birth. Making use of national-level routinely collected data, we included more than 1·5 million individual records in our analysis, including more than 55 000 babies born after implementation of COVID-19 mitigation measures in the Netherlands. Because more than 99% of babies in the Netherlands undergo neonatal dried blood spot screening,19 and very few babies in the dataset had missing outcome data, our data are highly representative. By applying a quasi-experimental approach, our study progresses substantially from earlier uncontrolled before-after studies, thus facilitating causal interpretation of the observed link between the COVID-19 mitigation measures and reduced preterm births.25, 26, 27 Additionally, our findings were robust in the various model specifications.

Our study also has limitations. Given the unanticipated nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated mitigation measures, we had to use a retrospective approach to data collection. As in any registry-based study, there could have been registration errors, and a very small proportion of individuals had missing data. Cross-validation against Perined suggested very little temporal variation in comparability of the data or missing variables, which if present, should have been captured by our difference-in-regression-discontinuity design. Extremely preterm and very-low-birthweight births were slightly underrepresented in our dataset as compared with Perined. This was anticipated because, unlike our dataset, Perined includes babies born between 22 weeks and 0 days and 23 weeks and 6 days and stillbirths.31 For obvious reasons, stillborn babies and those dying in the first few days after birth did not contribute data to the neonatal screening programme, so they were missing from our dataset. Our validation indicates that this relative underrepresentation was not differential over time and is therefore unlikely to have affected our findings. Survival of preterm babies improved over the study period, which would have biased our findings towards the null. We excluded babies born at less than 24 weeks gestation, because they are rarely offered active treatment in the Netherlands.21 Given their very low number (n=18) this exclusion is not expected to have affected our findings. Our dataset did not have individual-level information on relevant covariates, including socioeconomic status, ethnicity, parity, and preeclampsia. Therefore, we could not discern whether changes in demographic composition of the population following the COVID-19 pandemic (eg, through short-term migration) might have contributed to the findings. Absence of information on method of delivery and labour induction meant we could not assess whether the COVID-19 mitigation measures had a differential effect on spontaneous versus induced preterm births.

Our study builds on earlier work in several ways, including in the use of a robust quasi-experimental method and a much larger sample size.25, 26, 27 In the Irish study,3 proportions of extremely-low-birthweight and very-low-birthweight births were lower in Jan 1–April 30, 2020, than in the same period in the preceding 19 years;3 however, the numbers of observed versus anticipated extremely-low-birthweight (none vs four) and very-low-birthweight births (three vs 11) were very small. Furthermore, lockdown measures were implemented on March 12 in Ireland, rather than Jan 1, complicating causal interpretation. Similar to our study, the Danish study2 used national data from the neonatal dried blood spot screening programme. We calculated that only one extremely preterm birth had been observed in the Danish study in the first month following lockdown, where five to six were expected. Again, this is a large relative reduction but a small reduction in absolute terms. The observed reduction in preterm births in Denmark and Ireland predominantly affected the smallest babies,2, 3 whereas the decrease was fairly constant across gestational age strata in our study. The vast majority of preterm babies are born moderately to late preterm (ie, 32 weeks and 0 days to 36 weeks and 6 days), and our data suggest that prevention might be possible for all levels of prematurity. A comparison of birth outcomes in a London (UK) hospital before and after the COVID-19 pandemic started revealed no changes in the incidence of births before 34 weeks or 37 weeks gestation.32 Again, this study had a small sample size and it did not specifically investigate the effect of the lockdown. The authors noted an increase in stillbirths of six per 1000 births following the COVID-19 pandemic.32 In the Netherlands, stillbirth rates (from 22 weeks gestation) have fluctuated between 4·6 per 1000 births and 5·7 per 1000 births between 2010 and 2018.16 As more recent information on stillbirths was unavailable, we could not discern whether a small part of the observed reduction in preterm births occurred at the expense of an increase in stillbirths.

The aetiology of spontaneous preterm birth, which accounts for roughly two-thirds of all preterm births, is largely obscure and probably multifactorial, hampering effective prevention.33 Many of the known risk factors for preterm birth might be affected by implementation of COVID-19 mitigation measures. These risk factors include asymptomatic maternal infection, which through vertical transmission, can cause intrauterine infection, initiating a cascade resulting in preterm birth.33 Physical distancing and self-isolation, lack of commuting, closing of schools and childcare facilities, and increased awareness of hygiene (eg, hand washing) all reduce contact with pathogens and, accordingly, risk of infection. Timing of the observed preterm birth reductions in our study suggests that hygiene measures and anticipatory behavioural changes might have been instrumental. Additionally, closure of most businesses and obligatory home assignments probably resulted in less physically demanding work, less shift work, less work-related stress, optimisation of sleep duration, uptake of maternal exercise indoors and outdoors, and increased social support, which could all have a positive effect. Substantial reductions in air pollution have also been reported following COVID-19 mitigation measures,34 including in the Netherlands.35 Given the recognised increased risk of delivering preterm when exposed to air pollution,36 this finding could explain part of the observed reductions. Because a large minority of preterm births are induced, usually for maternal or fetal health concerns, changes in obstetric practice or care-seeking behaviour of pregnant women might also have contributed. Relatively few women deliver by primary caesarean section in the Netherlands, and these are typically medically indicated and done near-term.37 Changes in primary caesarean section rates are therefore unlikely to explain the findings. Substantial evidence indicates that the pandemic and associated lockdown measures have aggravated existing health and socioeconomic inequalities within populations.29, 30 In this regard, the signal in our data—albeit not statistically significant—suggesting that the reductions in preterm births were confined to people living in high-socioeconomic-status neighbourhoods is of considerable concern and requires further study.

Preterm birth is the primary contributor to mortality and morbidity in early childhood.9 Survivors are at increased risk of long-term negative consequences, including adverse cognitive and motor development,11, 12 behavioural and mental health problems,10 and respiratory disorders.13 Globally, the incidence of preterm birth is on the rise,9 and current options for prevention are very limited.14 Here, we show that national introduction of COVID-19 mitigation measures in the Netherlands was associated with a considerable reduction in preterm births, substantiating preliminary findings from other countries.2, 3 COVID-19 Law Lab shows that COVID-19 mitigation measures have been implemented across countries with substantial variation in timing, content, and comprehensiveness. Similarly, the various risk factors for preterm delivery that might be responsive to lockdown measures also vary across populations. Evidence suggests that the lockdown in Nepal had a negative effect on perinatal outcomes, highlighting the need for additional studies in low-resource settings.38 International collaborative efforts now underway will be key to incorporating these sources of variation in innovative global evaluations to further study the link between COVID-19 mitigation measures and preterm births. Identification of the underlying mechanisms is an essential next step and will require exploration of differential impact between spontaneous and induced preterm deliveries and across demographic strata, including socioeconomic status and ethnicity. Concomitant changes in stillbirths require evaluation, and exploration of possible links with changes in air pollution, mobility patterns, and care seeking and provision is needed. These investigations are pivotal to informing the development of much needed novel preventive strategies for preterm birth.

Data sharing

The authors are open to sharing statistical codes and study data. Agreement of the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, the data provider, will be required for any data sharing.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Roger Venema (National Institute for Public Health and the Environment) for preparing the data extract and Martin de Vries (National Institute for Public Health and the Environment) for facilitating data provision.

Contributors

JVB conceived the study. JVB and LCMB developed the study protocol with the involvement of EAPS and IKMR. JVB, LBO and LCMB analysed the data. All authors were involved in interpreting the data. JVB wrote the draft manuscript and all authors provided input at the writing stage. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Been JV, Sheikh A. COVID-19 must catalyse key global natural experiments. J Glob Health. 2020;10 doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.010104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedermann G, Hedley PL, Baekvad-Hansen M. Danish premature birth rates during the COVID-19 lockdown. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2020 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319990. published online Aug 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Philip RK, Purtill H, Reidy E. Reduction in preterm births during the COVID-19 lockdown in Ireland: a natural experiment allowing analysis of data from the prior two decades. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.03.20121442. published online June 5. (preprint) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu Patiënt met nieuw coronavirus in Nederland. Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu. 2020. https://www.rivm.nl/nieuws/patient-met-nieuw-coronavirus-in-nederland

- 5.Rijksoverheid . Rijksoverheid; 2020. Hygiënemaatregelen van belang om verspreiding coronavirus tegen te gaan.https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/03/09/hygienemaatregelen-van-belang-om-verspreiding-coronavirus-tegen-te-gaan [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rijksoverheid . Rijksoverheid; 2020. Nieuwe maatregelen tegen verspreiding coronavirus in Nederland.https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/03/12/nieuwe-maatregelen-tegen-verspreiding-coronavirus-in-nederland [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rijksoverheid . Rijksoverheid; 2020. Aanvullende maatregelen onderwijs, horeca, sport.https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/03/15/aanvullende-maatregelen-onderwijs-horeca-sport#:~:text=Zondag%2015%20maart%20heeft%20het,)%20en%20sport%2D%20en%20fitnessclubs [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rijksoverheid . Rijksoverheid; 2020. Aanvullende maatregelen 23 maart.https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/03/24/aanvullende-maatregelen-23-maart [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e37–e46. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franz AP, Bolat GU, Bolat H. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and very preterm/very low birth weight: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;141 doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Twilhaar ES, Wade RM, de Kieviet JF, van Goudoever JB, van Elburg RM, Oosterlaan J. Cognitive outcomes of children born extremely or very preterm since the 1990s and associated risk factors: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:361–367. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vollmer B, Stålnacke J. Young adult motor, sensory, and cognitive outcomes and longitudinal development after very and extremely preterm birth. Neuropediatrics. 2019;50:219–227. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1688955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Been JV, Lugtenberg MJ, Smets E. Preterm birth and childhood wheezing disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matei A, Saccone G, Vogel JP, Armson AB. Primary and secondary prevention of preterm birth: a review of systematic reviews and ongoing randomized controlled trials. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;236:224–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dutch Society for Obstetrics and Gynaecology . Dutch Society for Obstetrics and Gynaecology; 2018. Richtlijn basis prenatale zorg: opsporing van de belangrijkste zwangerschapscomplicaties bij laag-risico zwangeren (in de 2e en 3e lijn)https://www.nvog.nl/kwaliteitsdocumenten/richtlijnen/perinatologie/attachment/basis-prenatale-zorg-2de-en-3de-lijn-1-0-28-05-2015 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perined . Perined; 2019. Perinatale zorg in Nederland anno 2018.https://assets.perined.nl/docs/fc23b860-a5ff-4ef6-b164-aedf7881cbe3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institute for Public Health and the Environment Hoe komen de gegevens in een informatiesysteem? National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. https://www.pns.nl/juridische-informatie-screeningen-bij-zwangeren-en-pasgeborenen/hoe-komen-gegevens-in-informatiesysteem

- 18.Ministry of Public Health, Welfare, and Sports . National Institute for Public Health and the Environment; 2019. Draaiboek hielprikscreening: bijzondere situaties.https://draaiboekhielprikscreening.rivm.nl/uitvoering-hielprik/bijzondere-situaties [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of Public Health, Welfare, and Sports . National Institute for Public Health and the Environment; 2019. Monitor van de neonatale hielprikscreening 2018.https://www.pns.nl/documenten/monitor-van-neonatale-hielprikscreening-2018 [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute for Public Health and the Environment . National Institute for Public Health and the Environment; 2018. Voorbeeld hielprikkaart.https://www.rivm.nl/documenten/voorbeeld-hielprikkaart [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Laat MW, Wiegerinck MM, Walther FJ. Richtlijn. Perinataal beleid bij extreme vroeggeboorte. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2010;154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute for Public Health and the Environment Juridische informatie. National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. https://www.pns.nl/hielprik/juridische-informatie

- 23.National Institute for Public Health and the Environment Sociaaleconomische status. 2017. https://www.volksgezondheidenzorg.info/onderwerp/sociaaleconomische-status/regionaal-internationaal/regionaal#node-sociaaleconomische-status.Volksgezondheidenzorg.info

- 24.Hoftiezer L, Hof MHP, Dijs-Elsinga J, Hogeveen M, Hukkelhoven C, van Lingen RA. From population reference to national standard: new and improved birthweight charts. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:383.e1–383.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venkataramani AS, Bor J, Jena AB. Regression discontinuity designs in healthcare research. BMJ. 2016;352 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bor J, Moscoe E, Mutevedzi P, Newell M-L, Bärnighausen T. Regression discontinuity designs in epidemiology: causal inference without randomized trials. Epidemiology. 2014;25:729–737. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Craig P, Katikireddi SV, Leyland A, Popham F. Natural experiments: an overview of methods, approaches, and contributions to public health intervention research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:39–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bertens LCM, Burgos Ochoa L, Van Ourti T, Steegers EAP, Been JV. Persisting inequalities in birth outcomes related to neighbourhood deprivation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74:232–239. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-213162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;324:782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abrams EM, Szefler SJ. COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:659–661. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel RM, Kandefer S, Walsh MC. Causes and timing of death in extremely premature infants from 2000 through 2011. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:331–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khalil A, von Dadelszen P, Draycott T, Ugwumadu A, O'Brien P, Magee L. Change in the incidence of stillbirth and preterm delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324:705–706. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bauwens M, Compernolle S, Stavrakou T. Impact of coronavirus outbreak on NO2 pollution assessed using TROPOMI and OMI observations. Geophys Res Lett. 2020;47 doi: 10.1029/2020GL087978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mühlberg B. NL Times; 2020. Coronavirus response leads to big drop in air pollution.https://nltimes.nl/2020/03/27/coronavirus-response-leads-big-drop-air-pollution [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bekkar B, Pacheco S, Basu R, DeNicola N. Association of air pollution and heat exposure with preterm birth, low birth weight, and stillbirth in the US: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seijmonsbergen-Schermers AE, van den Akker T, Rydahl E. Variations in use of childbirth interventions in 13 high-income countries: a multinational cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2020;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kc A, Gurung R, Kinney MV. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic response on intrapartum care, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality outcomes in Nepal: a prospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1273–e1281. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30345-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors are open to sharing statistical codes and study data. Agreement of the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, the data provider, will be required for any data sharing.