Abstract

Background

Herein, we propose a novel RCT study to collect preliminary data on the impact of a 24-week home-based exercise program that can improve prognosis, physical function, and quality of life (QoL) in men with prostate cancer (PCa). This study will provide data on the feasibility of conducting a home-based exercise study and pilot data on the impact of exercise on circulating concentrations of biomarkers reported in the literature to be beneficial for the prognostication of PCa.

Methods/design

Thirty male patients, clinically-diagnosed with prostate cancer under active surveillance, will be recruited to participate in a 2-arm, 24-week home-based program. Random allocation to each arm - intervention, and control – will be performed in a 1:1 ratio. Participants assigned to the intervention group will perform 30 min of light-to-moderate intensity walking five days a week (40–60% heart rate reserve) and three sets of 15 repetitions of light callisthenic exercises (bodyweight squats, incline push-ups, and hip thrusts) 3 days a week. Participants randomized to the control group will maintain normal activity throughout the 24 weeks. Four visits occurring at baseline, 12-, 18-, and 24-weeks will be used to assess QoL, body composition, prognostic biomarker concentrations, and overall physical function. Primary endpoints include significant changes in prognostic biomarkers. Secondary endpoints include changes in quality of life, physical function and body composition.

Discussion

This study should demonstrate preliminary evidence that a home-based exercise intervention can impact biomarkers of progression while improving quality of life, physical function and body composition. Results from this study have the potential to promote health and wellness while minimizing cancer progression in men with PCa.

Physical activity after a cancer diagnosis has been reported to be associated with better cancer-specific and overall survival in individuals diagnosed with PCa. The role of a healthy diet and sufficient physical activity in cancer prevention have been well documented [[1], [2], [3]]. Unfortunately, even after the diagnosis of prostate cancer, men do not lose weight without directed guidance [4]. The lack of exercise can increase an individual's risk of recurrence or developing new cancers [5]. Increasing attention is now being given to the role of lifestyle in cancer survivorship. There is a growing body of evidence for lifestyle interventions that aim to promote physical activity as having the potential to counter some of the adverse effects of cancer treatments, disease progression, and other health outcomes [[6], [7], [8]]. Exercise performed 2–3 times a week has been shown to improve physical fitness, functional performance, and quality of life (QoL) in men with PCa [[9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]]; however, few men with PCa exercise regularly and do not meet national physical activity guidelines [12,18,19]. A potential explanation for the lack of exercise in men with PCa is the absence of a structured, home-based exercise program. While studies have shown positive effects of use in men with PCa [10,14,16,20,21], little is known about how physical activity affects tumor physiology. Of further significance, patients on active surveillance that progress to active treatment with intermediate-term follow-up have ranged from 14% to 41%, requiring the need for non-therapeutic interventions to modify the trajectory of this disease [22].

The primary objective of this pilot study is to gather preliminary data regarding the impact of a novel, 24-week home-based exercise program on PCa biomarkers associated with recurrence and metastasis of PCa in men under active surveillance.

1. Prognostic biomarkers associated with prostate cancer

Various biomarkers have been used for the diagnosis and follow-up of PCa. The most common biomarker used is prostate specific antigen (PSA). However, only one-quarter of men displaying elevated PSA levels in the blood are associated with PCa [23]. For this reason, our study team has turned to other biomarkers to determine the impact of exercise on disease progression more accurately. Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a type II integral membrane glycoprotein that is overexpressed in the epithelial cells of PCa patients [24]. Literature has shown PSMA has a 94.5% specificity to PCa progression [24]. Early prostate cancer antigen (EPCA) is a prostate cancer-associated nuclear structural protein displaying sensitivity and specificity for prostate cancer. EPCA has been found to be significantly elevated in localized PCa and strongly predicted cancer progression [25]. Urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) and its receptor (uPAR) have been connected with PCa stage and bone metastases [26]. Preoperative plasma uPA is a strong predictor of biochemical recurrence [27]. Elevated levels of both uPA and uPAR are associated with aggressive biochemical recurrence, including the development of distant metastasis, suggesting an association with occult metastatic disease [27]. While tumor biopsies following an exercise intervention fall outside the scope of current practices in PCa treatment for active surveillance patients, these biomarkers have the potential to act as circulating biopsy of the tumor.

2. Objectives

The overarching hypothesis for this study is that the home-based exercise program participants will have significantly lower concentrations of circulating biomarkers compared to their non-exercising counterparts.

3. Primary objective

To demonstrate the impact of a home-based exercise program versus waitlist control to modulate circulating prognostic biomarkers PSA, PSMA, EPCA, uPA, and uPAR in men with prostate cancer under active surveillance.

4. Secondary objectives

To determine the effect of a home-based exercise program versus waitlist control on:

-

i

Physical Function

-

ii

Quality of Life

-

ii

Body Composition

To determine the feasibility (including economic, technical, legal, and scheduling considerations) of completing a home-based exercise randomized controlled trial.

To determine the occurrence of adverse effects of the home-based exercise intervention in men with prostate cancer under active surveillance.

5. Methods and analysis

5.1. Trial design

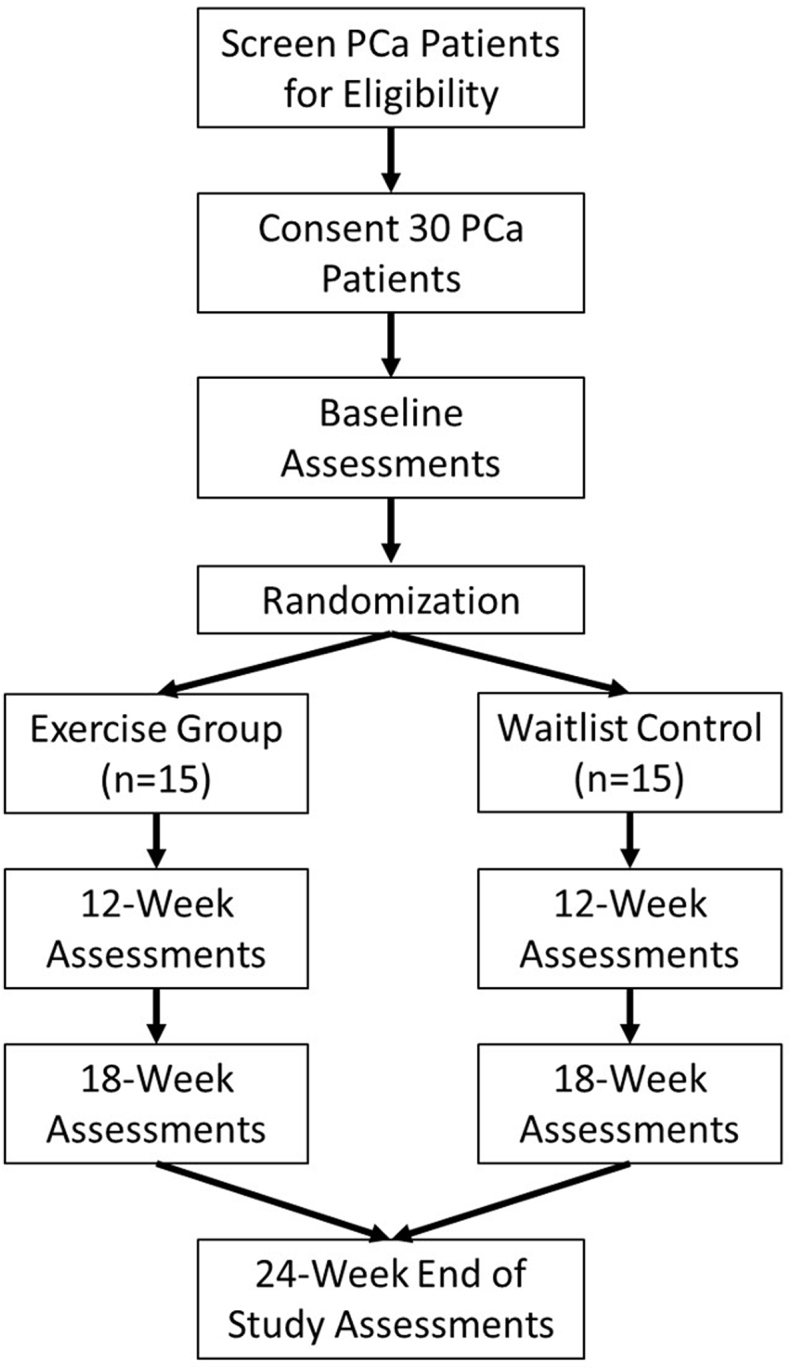

The prospective study is a single-center, randomized controlled trial. We randomly assign eligible participants to either the home-based exercise group or a waitlist control group. Fig. 1 shows the flow chart of the study. This study protocol follows the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials statement recommendations [28].

Fig. 1.

Study design.

5.2. Participants

This study plans to enroll 30 men with prostate cancer under active surveillance with 15 men in each arm to have 12 completing the study in each arm. Patients will be recruited from the San Antonio community. Patients who meet the inclusion criteria and sign the informed consent form will be enrolled in this study. Based on the feasibility nature of this study, a sample size calculation is not appropriate. Based on a preponderance of published feasibility and pilot studies, a minimum sample of 15 participants per group to complete the study was chosen to estimate parameters for future studies [[29], [30], [31]].

5.3. Eligibility criteria

5.3.1. Inclusion criteria

-

•

men aged 40 years or older

-

•

diagnosed with prostate cancer

-

•

under active surveillance

-

•

Gleason score of 3 + 3

-

•

participants willing and able to provide consent to participate in the study.

5.3.2. Exclusion criteria

-

•

severe cardiac disease (New York Heart Association class III or greater)

-

•

angina

-

•

severe osteoporosis

-

•

uncontrolled hypertension (blood pressure > 160/95 mm Hg)

-

•

uncontrolled sinus tachycardia (>120 beats per minute)

-

•

uncontrolled congestive heart failure third-degree atrio-ventricular heart block, active pericarditis or myocarditis, recent embolism, thrombophlebitis, deep vein thrombosis, resting ST displacement (>3 mm),

-

•

uncontrolled diabetes,

-

•

uncontrolled pain,

-

•

cognitive impairment,

-

•

history of falls due to balance impairment or loss of consciousness,

-

•

severe neuromusculoskeletal conditions that limit their ability to perform a walking exercise (including ataxia, peripheral or sensory neuropathy, unstable bone lesion, severe arthritis, lower limb fractures within six months, lower limb amputation).

6. Ethics

This trial is approved by the Institutional Review Board at our three affiliated institutions: the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, the Audie L. Murphy Memorial Veterans Administration Hospital, and our National Cancer Center Institute designated cancer center the Mays Cancer Center at UT Health San Antonio. All participants meeting inclusion criteria will be eligible for participation. The Principal Investigator will prescreen patients by reviewing the medical records. Eligible patients will be approached in the clinic and invited to participate. We require the informed consent of all participants to participate in the study. We also have put in place data security, data coding, and restricted access to electronic data and case report forms to assure subject confidentiality. Any deviations from the protocol, breach of confidentiality, or reportable adverse events will be reported to the IRB and Data Safety Monitoring Board at the Mays Cancer Center.

7. Randomization

Patients eligible to participate in this study will be allocated to either the exercise group or waitlist control group (1:1) based on a pre-specified randomization schedule. A sample of 15 men in each group will be enrolled with the goal of having 12 completers in each group.

8. Interventions

8.1. Home-based exercise intervention

The intervention will include a combination of both aerobic and calisthenic exercises. The aerobic portion of the intervention will include five days of light-to-moderate intensity walking for 30 min. The intensity will be set at 40–60% of the individual's heart rate reserve using the Karvonen formula (Exercise HR = % of target intensity (HRmax – HRrest) + HRrest) [32]. The study team will provide participants their targeted HR range, and each participant will be taught how to palpate and calculate HR before the beginning of the program. The callisthenic exercises will be done 3 times a week. Exercises will consist of three sets of 15 repetitions of: bodyweight squats, incline push-ups, and hip thrusts. If these exercises cannot be performed, modified, lower intensity exercises such as sit-to-stand, wall push up, and pelvic tilt can be replaced. These exercises are aimed at increasing the strength and endurance of the major muscle groups of the body. Individuals in this group will be given a pocket guide with instructions on how to safely perform the exercises and document the completion of the exercises. A Fitbit activity monitor will be provided to this group to ensure compliance with the exercise protocol.

8.2. Waitlist control allocation

Participants assigned to the waitlist control group will be asked to maintain normal activity for the 6-month portion of this study. Each participant will be assigned a Fitbit activity monitor to ensure no changes are made to their normal daily activity. After the 6-month study period is complete, individuals in this group will be invited to participate in the exercise program and will be tracked for an additional 6 months.

9. Schedule of events

All participants will be asked to attend 4 study visits: baseline, 12, 18 and 24 weeks (Table 1). At the baseline visit and 24 week visit, participants will be assigned a Fitbit activity monitor (baseline only) and provide a blood sample, complete two QoL surveys (i.e., Health-Related Quality of Life; SF-36, and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness – Fatigue; FACIT-F), perform a 6-min walk test (6MWT) intended to asses overall physical function, and undergo body composition assessments to include: waist and arm circumference and a 3-site skinfold (chest, abdomen, and thigh). During visits 2 and 3 (weeks 12 and 18, respectively), participants will provide a blood sample and undergo the aforementioned body composition assessments.

Table 1.

Health-Related Quality of Life (SF-36) is designed to assess the health status of patients and has been used previously in this population [33]. The SF-36 assesses eight components of quality of life (physical functioning, role functioning, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, mental health, and emotional health) that is evidence generated with well-established reliability and validity to support its use.

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) is a self-reported survey evaluating the impact of fatigue in the patient population [34]. The FACIT-F is a 13-item survey rated on a 5-point scale deemed reliable and valid in measuring fatigue.

10. Participant adherence monitoring

Weekly phone calls to all participants will be conducted to ensure participants are engaging in the study appropriately. Exercise adherence within the intervention group will be monitored by the study team using the Fitbit activity monitors. Participants will also be provided with an exercise log booklet to document the number of repetitions and set completed for the body weight-based exercises. Adherence will be based on the participant's ability and willingness to perform prescribed activities. Participants unwilling to participate will be discontinued from the study.

11. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis will be performed using IBM SPSS 19.0 software. A 2-group multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) will be used to compare changes in biomarkers, physical function, body composition, and QoL between the exercise group and the control group. Pearson's Product Moment Correlation will be used to measure associations between biomarkers to body composition, physical function, and QOL measures. A value of p < 0.05 will be considered statistically significant, and all statistical tests will be two-tailed. The results of this study will be used to calculate power and determine the sample size for future research questions in this field.

12. Handling of patient withdrawal

Patients may withdraw from the study at any time during the study. Patients may also be withdrawn from the study for not following related study procedures or for the benefit of the patient as determined by study investigators. We will record all the reasons for study discontinuation to document compliance with the study and inform future trials. All attempts will be made to keep participants in this study. Patients will be withdrawn for non-compliance if they meet any combination of the following: inactivity for three consecutive weeks; and missing two consecutive study appointments where outcome variables are collected. Patients who discontinue study participation will not be replaced. In the case study, discontinuation is due to an adverse event; such patients will be closely monitored until the resolution or stabilization of this adverse event. This may mean that follow-up will continue after the patient has completed the end of study procedures. Although data on that adverse event will continue to be captured, even beyond the last visit, only those that occur up through the last visit will be recorded.

13. Data management

Each participant will be assigned a unique study code. Participant identifiers collected include name, address, phone number/email address, and date of birth. The list connecting the participant to the study code will be kept electronically on a secure server and password protected. Only the Principal Investigator or a designee will have access to this list. All collection, processing, and storing tubes for biological samples will be labeled using the study code number. Surveys will be completed electronically and linked to the participants' electronic data files. Electronic data will be managed using REDCap, an electronic data management system.

The findings of this study will be presented at international scientific conferences and submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals. All authors will be required to have made a significant contribution to the abstracts, presentations, and manuscripts and no professional writers will be engaged in preparing these materials. Only de-identified data will be presented.

14. Discussion

Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in American males, exceeded only by lung cancer [35]. Although age is one of the most significant risk factors for prostate cancer, behavioral interventions have been reported to augment the disease risk, trajectory, and promote survivorship [36]. Epidemiological data shows positive associations between body mass index, sedentary lifestyle, and prostate cancer risk [37]. Likewise, active lifestyles before and after diagnosis can affect morbidity and mortality in prostate cancer survivors [[38], [39], [40]].

There is a lack of research on individuals with active surveillance and even less on the home-based exercise interventions. Our hypothesis for the lack of adherence to physical activity guidelines is the inability of individuals to have prescribed programs that are supervised by a healthcare provider than can be done at home. Even though patients on active surveillance have a slow progressing tumor, there is a moderate risk of tumor progression that requires medical treatment [41]. Therefore, it is essential to study this population.

There is a lack of research on the effects of exercise on prognostic biomarkers. Much of the work in exercise oncology is descriptive. Thus, the outcomes of this trial will provide early insights into the role of exercise, and a medical intervention that can be used to manipulate biomarkers of prognosis in a patient group is that understudied. Most exercise interventions are short durations, i.e., 12 weeks on average [11,[42], [43], [44], [45]]. While that may be standard for progressive protocols that mimic micro, meso and macro cycles of exercise programs typically prescribed to healthy individuals, there is a need to study longer interventions for adherence, compliance and long-term effects of exercise.

The strengths of this protocol is that we will be conducting a 6-month intervention while collecting biological samples at multiple times points, including 12 and 18 weeks, that can provide insight into the kinetics of biomarkers and outcomes of quality of life. An additional strength is the ability of the control group to cross over into the exercise group will help in control group adherence. Our approach to generating maximal data is two-fold: 1) Fitbit activity monitoring will provide us with continuous data on individual activity patterns, including leisure activity, work-specific activity, and the prescribed exercise intervention. 2) Using a waitlist control group will ultimately allow us to assess a larger study sample that completes the exercise intervention allowing us to conduct a true-experimental study and a quasi-experimental study within a single study design.

Our study is not without limitations. One obvious limitation is the lack of a powered sample size. However, based on previous publications reporting on average sample sizes for pilot and feasibility studies, the sample we selected should provide us with the necessary information to conduct a more extensive, multisite clinical trial powered based on the outcomes of this study. Another limitation of this study is the lack of control in participant diets. The link between diet and tumor progression has been reported. However, the complexity of diet modification and the confounding variability in diets within our patient groups makes it difficult in stratifying groups based on diet. Finally, the lack of tissue samples limit our ability to investigate actual changes in the tumor in response Therefore, any conclusions that are made from this study can only speculate what changes may be occurring in situ. However, using PSA, a clinically validated biomarker in addition to the other biomarkers described earlier, will provide us with valuable information in the form of a liquid biopsy to understand how the home-based intervention effects prognosis.

In conclusion, the findings of this study will provide preliminary data regarding the effects of a home-based exercise program on biomarkers associated with tumor progression in men with prostate cancer. These findings will provide rational on whether larger, multi-year studies are needed.

15. Trial registration number

Authors contribution

DP and ML conceived the study and initiated the study design. DP, AG, BS, SV and ML are involved in the study implementation. DP is funding holder. All authors contributed to finalizing the study protocol and approved the final manuscript.

Funding statement

This study was primarily funded by an internal research grant from the School of Nursing Advisory Council at The University of Texas Health Science Center as San Antonio (DP) and a grant from the Department of Education (P031S150048; DP). The work was also supported by the National Cancer Institute designated UT Health San Antonio Mays Cancer Center (P30 CA054174).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.McTiernan A. Mechanisms linking physical activity with cancer. Nat. Rev. Canc. 2008;8(3):205–211. doi: 10.1038/nrc2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsushita M., Fujita K., Nonomura N. Influence of diet and nutrition on prostate cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(4):1447. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joanna K., Aboul-Enein H. What are the links of prostate cancer with physical activity and nutrition?: a systematic review article. Iran. J. Public Health. 2016;45(12):1558. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liss M.A., Schenk J.M., Faino A.V., Newcomb L.F., Boyer H., Brooks J.D. A diagnosis of prostate cancer and pursuit of active surveillance is not followed by weight loss: potential for a teachable moment. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016;19(4):390–394. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2016.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao Y., Ma J. Body mass index, prostate cancer–specific mortality, and biochemical recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Canc. Prev. Res. 2011;4(4):486–501. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart N.H., Galvão D.A., Newton R.U. Exercise medicine for advanced prostate cancer. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care. 2017;11(3):247–257. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galvao D.A., Spry N., Denham J., Taaffe D.R., Cormie P., Joseph D. A multicentre year-long randomised controlled trial of exercise training targeting physical functioning in men with prostate cancer previously treated with androgen suppression and radiation from TROG 03.04 RADAR. Eur. Urol. 2014;65(5):856–864. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cormie P., Galvao D.A., Spry N., Joseph D., Chee R., Taaffe D.R. Can supervised exercise prevent treatment toxicity in prostate cancer patients initiating androgen deprivation therapy: a randomised controlled trial. BJU Int. 2014;115(2):256–266. doi: 10.1111/bju.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galvao D.A., Nosaka K., Taaffe D.R., Spry N., Kristjanson L.J., McGuigan M.R. Resistance training and reduction of treatment side effects in prostate cancer patients. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006;38(12):2045–2052. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000233803.48691.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galvao D.A., Spry N., Denham J., Taaffe D.R., Cormie P., Joseph D. A multicentre year-long randomised controlled trial of exercise training targeting physical functioning in men with prostate cancer previously treated with androgen suppression and radiation from TROG 03.04 RADAR. Eur. Urol. 2013;65(5):856–864. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galvao D.A., Spry N., Taaffe D.R., Denham J., Joseph D., Lamb D.S. A randomized controlled trial of an exercise intervention targeting cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors for prostate cancer patients from the RADAR trial. BMC Canc. 2009;9:419. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keogh J.W., Shepherd D., Krageloh C.U., Ryan C., Masters J., Shepherd G. Predictors of physical activity and quality of life in New Zealand prostate cancer survivors undergoing androgen-deprivation therapy. N. Z.Med. J. 2010;123(1325):20–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell S.A., Beck S.L., Hood L.E., Moore K., Tanner E.R. Putting evidence into practice: evidence-based interventions for fatigue during and following cancer and its treatment. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2007;11(1):99–113. doi: 10.1188/07.CJON.99-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monga U., Garber S.L., Thornby J., Vallbona C., Kerrigan A.J., Monga T.N. Exercise prevents fatigue and improves quality of life in prostate cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007;88(11):1416–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pekmezi D.W., Demark-Wahnefried W. Updated evidence in support of diet and exercise interventions in cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(2):167–178. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.529822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonn G.A., Aronson W., Litwin M.S. Impact of diet on prostate cancer: a review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005;8(4):304–310. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaskin C.J., Fraser S.F., Owen P.J., Craike M., Orellana L., Livingston P.M. Fitness outcomes from a randomised controlled trial of exercise training for men with prostate cancer: the ENGAGE study. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2016;10(6):972–980. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0543-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellizzi K.M., Rowland J.H., Jeffery D.D., McNeel T. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23(34):8884–8893. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coups E.J., Ostroff J.S. A population-based estimate of the prevalence of behavioral risk factors among adult cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Prev. Med. 2005;40(6):702–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen P.A., Dechet C.B., Porucznik C.A., LaStayo P.C. Comparing eccentric resistance exercise in prostate cancer survivors on and off hormone therapy: a pilot study. Pharm. Manag. PM R. 2009;1(11):1019–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segal R.J., Reid R.D., Courneya K.S., Malone S.C., Parliament M.B., Scott C.G. Resistance exercise in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21(9):1653–1659. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooperberg M.R., Carroll P.R., Klotz L. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: progress and promise. J. Clin. Oncol.: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(27):3669–3676. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.9738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obort A.S., Ajadi M.B., Akinloye O. Prostate-specific antigen: any successor in sight? Rev. Urol. 2013;15(3):97–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy G.P., Kenny G.M., Ragde H., Wolfert R.L., Boynton A.L., Holmes E.H. Measurement of serum prostate-specific membrane antigen, a new prognostic marker for prostate cancer. Urology. 1998;51(5, Supplement 1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao Z., Ma W., Zeng G., Qi D., Ou L., Liang Y. Preoperative serum levels of early prostate cancer antigen (EPCA) predict prostate cancer progression in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy. Prostate. 2012;72(3):270–279. doi: 10.1002/pros.21428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta A., Lotan Y., Ashfaq R., Roehrborn C.G., Raj G.V., Aragaki C.C. Predictive value of the differential expression of the urokinase plasminogen activation axis in radical prostatectomy patients. Eur. Urol. 2009;55(5):1124–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shariat S.F., Roehrborn C.G., McConnell J.D., Park S., Alam N., Wheeler T.M. Association of the circulating levels of the urokinase system of plasminogen activation with the presence of prostate cancer and invasion, progression, and metastasis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25(4):349–355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan A.-W., Tetzlaff J.M., Gøtzsche P.C., Altman D.G., Mann H., Berlin J.A. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Julious S.A. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharmaceut. Stat.: The Journal of Applied Statistics in the Pharmaceutical Industry. 2005;4(4):287–291. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Browne R.H. On the use of a pilot sample for sample size determination. Stat. Med. 1995;14(17):1933–1940. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Billingham S.A.M., Whitehead A.L., Julious S.A. An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom Clinical Research Network database. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013;13:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karvonen M.J. The effects of training on heart rate: a longitudinal study. Ann. Med. Exp. Biol. Fenn. 1957;35:307–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lubeck D.P., Litwin M.S., Henning J.M., Stoddard M.L., Flanders S.C., Carroll P.R. Changes in health-related quality of life in the first year after treatment for prostate cancer: results from CaPSURE. Urology. 1999;53(1):180–186. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yellen S.B., Cella D.F., Webster K., Blendowski C., Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 1997;13(2):63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA: A Cancer J. Clinician. 2017;67(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell K.L., Winters-Stone K.M., Wiskemann J., May A.M., Schwartz A.L., Courneya K.S. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019;51(11):2375–2390. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell K.L., Winters-Stone K.M., Patel A.V., Gerber L.H., Matthews C.E., May A.M. An executive summary of reports from an international multidisciplinary roundtable on exercise and cancer: evidence, guidelines, and implementation. Rehabilitation Oncology. 2019;37(4):144–152. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richman E.L., Kenfield S.A., Stampfer M.J., Paciorek A., Carroll P.R., Chan J.M. Physical activity after diagnosis and risk of prostate cancer progression: data from the cancer of the prostate strategic urologic research endeavor. Canc. Res. 2011;71(11):3889–3895. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedenreich C.M., Wang Q., Neilson H.K., Kopciuk K.A., McGregor S.E., Courneya K.S. Physical activity and survival after prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2016;70(4):576–585. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Nunzio C., Presicce F., Lombardo R., Cancrini F., Petta S., Trucchi A. Physical activity as a risk factor for prostate cancer diagnosis: a prospective biopsy cohort analysis. BJU Int. 2016;117(6B):E29–E35. doi: 10.1111/bju.13157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cooperberg M.R., Cowan J.E., Hilton J.F., Reese A.C., Zaid H.B., Porten S.P. Outcomes of active surveillance for men with intermediate-risk prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29(2):228. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.4252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antonelli J., Freedland S., Jones L. Exercise therapy across the prostate cancer continuum. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009;12(2):110–115. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2009.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferioli M., Zauli G., Martelli A.M., Vitale M., McCubrey J.A., Ultimo S. Impact of physical exercise in cancer survivors during and after antineoplastic treatments. Oncotarget. 2018;9(17):14005–14034. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galvao D.A., Taaffe D.R., Spry N., Joseph D., Newton R.U. Combined resistance and aerobic exercise program reverses muscle loss in men undergoing androgen suppression therapy for prostate cancer without bone metastases: a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28(2):340–347. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galvao D.A., Taaffe D.R., Spry N., Newton R.U. Exercise can prevent and even reverse adverse effects of androgen suppression treatment in men with prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2007;10(4):340–346. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]