ABSTRACT

Objective.

In 2010, the principle of proportionate universalism (PU) has been proposed as a solution to reduce health inequalities. It had a great resonance but does not seem to have been widely applied and no guidelines exist on how to implement it.

The two specific objectives of this scoping review were: (1) to describe the theoretical context in which PU was established, (2) to describe how researchers apply PU and related methodological issues.

Methods.

We searched for all articles published until 6th of February 2020, mentioning “Proportionate Universalism” or its synonyms “Targeted universalism” OR “Progressive Universalism” as a topic in all Web of Science databases.

Results.

This review of 55 articles allowed us a global vision around the question of PU regarding its theoretical foundations and practical implementation. PU principle is rooted in the social theories of universalism and targeting. It proposes to link these two aspects in order to achieve an effective reduction of health inequalities. Regarding practical implementation, PU interventions were rare and led to different interpretations. There are still many methodological and ethical challenges regarding conception and evaluation of PU interventions, including how to apply proportionality, and identification of needs.

Conclusion.

This review mapped available scientific literature on PU and its related concepts. PU principle originates from social theories. As highlighted by authors who implemented PU interventions, application raises many challenges from design to evaluation. Analysis of PU applications provided in this review answered to some of them but remaining methodological challenges could be addressed in further research.

Keywords: Health equity, health policy, socioeconomic factors

RESUMEN

Objetivo.

En 2010 se propuso el principio del universalismo proporcional como solución para reducir las desigualdades en materia de salud. Aunque tuvo una gran resonancia, no parece haber sido aplicado ampliamente y no existen directrices sobre cómo aplicarlo. Los dos objetivos específicos de esta revisión sistemática exploratoria fueron: 1) describir el contexto teórico en el que se estableció el universalismo proporcional, y 2) describir cómo los investigadores aplican el universalismo proporcional y las cuestiones metodológicas relacionadas.

Métodos.

Se buscó en todas las bases de datos de la Web of Science los artículos publicados hasta el 6 de febrero de 2020 que tuvieran como tema “universalismo proporcional” o sus sinónimos “universalismo dirigido” o “universalismo progresivo”.

Resultados.

Esta revisión de 55 artículos permitió tener una visión global del universalismo proporcional en cuanto a sus fundamentos teóricos y su aplicación práctica. El principio del universalismo proporcional se basa en las teorías sociales del universalismo y el direccionamiento, y propone vincular estos dos aspectos para lograr una reducción efectiva de las desigualdades en materia de salud. Respecto de su aplicación práctica, las intervenciones basadas en este principio son poco frecuentes y dan lugar a diferentes interpretaciones. Todavía existen muchos desafíos metodológicos y éticos en relación con la concepción y la evaluación de las intervenciones relacionadas con el universalismo proporcional, incluida la forma de aplicar la proporcionalidad y la identificación de las necesidades.

Conclusión.

En esta revisión se llevó a cabo un mapeo de la literatura científica disponible sobre el universalismo proporcional y sus conceptos relacionados. Este principio se basa en teorías sociales. Tal como lo destacaron autores que implementaron intervenciones de universalismo proporcional, su aplicación plantea muchos desafíos, desde el diseño hasta la evaluación. El análisis de las aplicaciones del universalismo proporcional presentado en esta revisión respondió a algunos de ellos, pero los desafíos metodológicos restantes requieren ser abordados en futuras investigaciones.

Palabras clave: Equidad en salud, política de salud, factores socioeconómicos

Health inequalities are an ubiquitous and widening problem around the world, very often described through the social gradient of health: whatever the indicator of deprivation (incomes, social category, etc.) considered, the more a person belongs to the most deprived classes, the worse his or her health will be (1). These inequalities exist within countries as well as among countries. One example among many, that the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) reports: “the difference in overall life expectancy among the countries of the PAHO region was over 19 years for both males and females in 2016” (2).

In 2010, the review Fair Society, Healthy Lives, proposed the principle of proportionate universalism (PU) as a solution to reduce these inequalities (3). “Actions should be universal, but with an intensity and a scale that is proportional to the level of disadvantage”: that is the exact definition of PU. Shortly after its publication this review had a great resonance among scholars from different fields and there were many encouraging or contradictory reactions (4-6). Moreover, a quick search with the keyword “proportionate universalism” shows that the principle has recently gained momentum. Despite this growing concern among researchers, with the exception of a few local policies in England and in European Nordic countries, the principle does not seem to have been widely applied.

To our knowledge, there are no guidelines on how to implement policies or health interventions fulfilling this principle and how to evaluate them. Understanding the theoretical referents could contribute to develop more efficient and successful applications. In the same way, analyses of health interventions or programmes referring to PU could highlight practical issues.

The objective of the scoping review was to map available literature referring to the concept of PU or its related concepts. The two specific objectives were: (1) to describe the theoretical context in which PU was established, (2) to describe how researchers apply PU and related methodological issues.

Material and Methods

Framework of the review

Given the large scope of the research question, its emergent nature and the heterogeneity of articles, we have conducted a scoping literature review in accordance with PRISMA-ScR and Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines (7,8). We have followed the five mandatory methodological steps proposed by Arksey and O’Malley and secondarily completed: 1) identifying the research question, 2) identifying relevant studies, 3) study selection, 4) charting the data, 5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results (9-11).

Information sources and search strategy

We searched for all sorts of articles published until 6th of February 2020, mentioning “proportionate universalism” or its synonyms “targeted universalism” OR “progressive universalism” as a topic in all Web of Science databases written in English or French. We used Web of science to allow us to find scientific papers from different fields.

Study selection

Each title and abstract were screened by two authors (FF, FA) and discrepancies were solved by discussion. We included articles that defined, analysed ins and outs, and described applications of PU or its related concepts. The search was limited to the public health or social policies context. Papers were excluded if not available or if they were not directly related to one of the above-mentioned concepts.

Analysis of articles

A reading grid was used to systematically analyse the articles. It contained: (1) characteristics of articles: author, region of the first author, type of article, field; (2) elements of definition for key-terms; and (3) objective, methods, main findings, and questions raised by authors regarding implementation of PU. Data were analysed using Excel.

Results

Articles characteristics

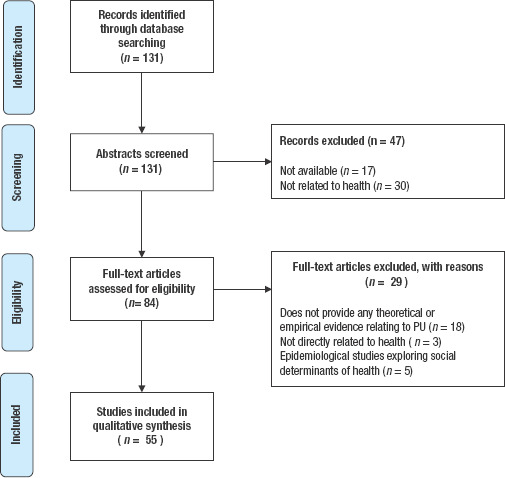

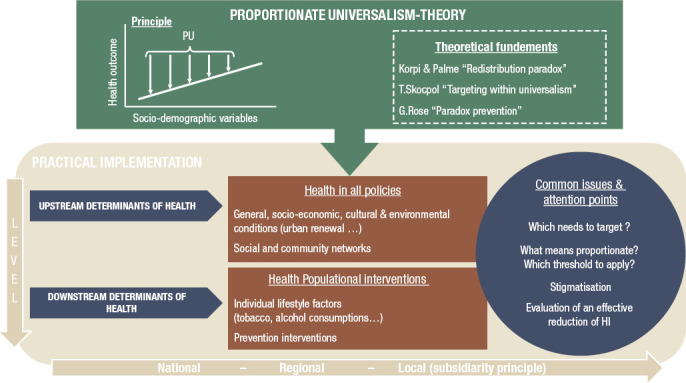

Our initial search returned 131 articles. After selection, 55 were finally included (Figure 1). Included articles were of different types (interventions, theoretical articles, reviews…). The majority of included studies concerned European countries (n=39), followed by countries from North and South America (n=9) (Table 1). 56.4% (n=31) of articles were published since 2016. The characteristics of health population interventions are described in Table 2. A graphical summary of the review is provided in Figure 2: it presents the theoretical context of PU and common questions raised by PU applications targeting upstream or downstream determinants.

FIGURE 1. Article selection.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of included articles (n = 55).

|

Field |

Country |

Publication year |

|---|---|---|---|

Social sciences, economics and political science |

|

|

|

Brady et al (21) |

Universalism/Targeting |

Germany |

2012 |

Brady et Bostic (28) |

Universalism/Targeting |

Germany/Ireland |

2015 |

Carey et al (39) |

Universalism/Targeting |

Australia |

2015 |

Carey et al (41) |

Universalism/Targeting |

Australia |

2016 |

Carey et al (18) |

Universalism/Targeting |

Australia |

2017 |

Fischer (20) |

Universalism/Targeting |

United Kingdom |

2010 |

Grogan et al (13) |

Universalism/Targeting |

United States |

2003 |

Horton et al (32) |

Universalism/Targeting |

United Kingdom |

2010 |

Imai (23) |

Universalism/Targeting |

India |

2007 |

Jacques (16) |

Universalism/Targeting |

Canada |

2018 |

Kabeer (29) |

Universalism/Targeting |

United Kingdom |

2014 |

Kim (25) |

Universalism/Targeting |

Japan |

2010 |

Kuivalainen et al (22) |

Universalism/Targeting |

Finland |

2010 |

Marchal et al (15) |

Universalism/Targeting |

Belgium |

2019 |

Skocpol (33) |

Universalism/Targeting |

United States |

1991 |

Corburn (65) |

Health in all policies |

United States |

2014 |

Brewster et al (53) |

Dental health |

United Kingdom |

2013 |

Briançon et al (64) |

Child obesity |

France |

2020 |

Dierckx et al (57) |

Maternal and Child health |

Belgium |

2019 |

Dodge et al (40) |

Maternal and Child health |

United States |

2019 |

Cruz-Martinez et al (17) |

Old pensions |

Latin America/Caribbean |

2019 |

Moffatt et al (67) |

Old pensions |

United Kingdom |

2007 |

Müller (24) |

Old pensions |

Bolivia |

2009 |

Neelsen et al (30) |

Targeted health Coverage |

Peru |

2017 |

Van Lancker et al (15) |

Single mothers poverty |

Europe |

2015 |

Van Lancker et al (14) |

Child poverty |

Europe |

2015 |

Van Vliet J (41) |

Not one in particular |

Sweden |

2018 |

Benach et al (46) |

Not one in particular |

Spain |

2012 |

Porcherie et al (43) |

Not one in particular |

France |

2017 |

Sannino et al (68) |

Not one in particular |

France |

2018 |

Public Health, Epidemiology |

|

|

|

Barboza et al (62) |

Maternal and Child health |

Sweden |

2018 |

Burström et al (37) |

Maternal and Child health |

Sweden |

2017 |

Barlow et al (61) |

Maternal and Child health |

United Kingdom |

2010 |

Bywater et al (52) |

Maternal and Child health |

United Kingdom |

2018 |

Hogg et al (73) |

Maternal and Child health |

United Kingdom |

2013 |

Thomson et al (35) |

Maternal and Child health |

United Kingdom |

2012 |

Cowley et al (54) |

Maternal and Child health |

United Kingdom |

2014 |

Morrison et al (56) |

Maternal and Child health |

United Kingdom |

2014 |

Maharaj et al (47) |

Maternal and Child health |

United Kingdom |

2012 |

Egan et al (49) |

Urban renewal |

United Kingdom |

2016 |

Guillaume et al (38) |

Cancer screening |

France |

2017 |

Guillaume et al (51) |

Cancer screening |

France |

2017 |

Legrand et al (50) |

Child obesity |

France |

2017 |

Mc Laren (31) |

Universalism/Targeting |

Canada |

2019 |

Rice P (39) |

Alcohol prevention |

United Kingdom |

2019 |

Vitus et al (70) |

Body-weight management |

Denmark |

2017 |

Welsh et al (55) |

Mental health, Pediatrics |

Australia |

2015 |

Bekken et al (74) |

Not one in particular |

Norway |

2018 |

Affeltranger et al (44) |

Not one in particular |

France |

2018 |

Goldblatt P (59) |

Not one in particular |

United Kingdom |

2016 |

Wiseman et al (75) |

Universal health Coverage |

Indonesia |

2018 |

Ethics |

|

|

|

Darquy et al (48) |

Cancer screening |

France |

2018 |

Lechopier et al (72) |

Cancer screening |

France |

2017 |

Moutel et al (71) |

Cancer screening |

France |

2019 |

Devereux S (63) |

Not one in particular |

United Kingdom |

2016 |

TABLE 2. Description of health population interventions (n = 9).

Author, year |

Reference principle |

Intervention description |

“Level of disadvantage” assessment |

Evaluation of inequalities reduction |

Main findings |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hogg et al, 2012 |

Progressive universalism |

Explore the assessment of vulnerability and support needs of families, from the perspectives of parents and HVs, with a particular focus on ?the Lothian Child Concern Model. |

Each family is offered four home visits by the HV between 10 days and 4–6 months after the birth, ?during which the parents and HV discuss the family’s health and health needs, and the HV provides information and advice as required. |

Individually, through home-visits |

Qualitative study (interviews of parents and health visitors) |

The study findings significant the concept of ‘progressive universalism’ that provides a continuum that intensity of support to families, depending on need. Mothers would like better partnership working with health visitors. |

Maharaj et al, 2012 |

PU |

1 To demonstrate that community paediatrics can contribute to reduction of health inequalities by providing services that are accessible to and preferentially used by children whose health is likely to be affected by deprivation. 2 To provide a template for others to improve and monitor equity in their services. |

New organisation of a pediatric service. Key features of the new service model are multi-agency working, accessibility, holistic assessment, comprehensive provision of services, and the fact that the service is available to all but able to respond proportionately to children with higher levels of need. |

Indices of Multiple Deprivation |

Access to care in the intervention area compared to a similar area, described by deprivation quintile |

The new patient contact rate for the most deprived children in the population was more than three times that of the least deprived [odds ratio (OR) 3.29, 95% confidence interval (CI) [ 2.76–3.93]. |

Guillaume et al, 2017 |

PU |

Assess the efficacy of MM in reducing social and geographic inequalities with regard to participation in breast cancer screening in a well-defined general population in a French territory. |

National breast cancer screening combined with ?mobile mammography in one rural department in France (Orne). Experimentation in one rural department in France |

Not specified |

Not specified |

After adjustment, invitation was associated with a significant increase in individual participation (odds ratio= 2.9) |

Legrand et al, 2017 Briançon et al, 2020 |

PU |

Evaluate the effectiveness of a school-based intervention to address social inequalities in adolescents who are overweight and the impact of the interventions on adopting healthy behaviors, quality of life, anxiety and depression. |

Standard-care management, according to the validated PRALIMAP trial was proposed for all adolescents, ?while strengthened-care management intending to address barriers was proposed for only socially less-advantaged adolescents of the intervention group. |

Family Affluence Scale score |

Comparison of the BMI after intervention among three groups constituted with results from Family Affluence Scale score |

Trend to superiority for the less-advantaged group receiving the strengthened care management (reduction of BMI -0,06 [-0,11 to -0,01]) |

Burstrom et al, 2017 Barboza, 2018 |

PU |

The intervention is expected to strengthen parents’ knowledge about children, improve the interaction between parents and children, increase the contacts of parents with other relevant societal actors, and strengthen their ?self-efficacy and well-being. |

Extended postnatal home visiting programme: the intervention consists of five extra home visits when the child is aged between 2–15 months, jointly by a child health nurse and a social service parental advisor, offered to all parents of first-born children attending Rinkeby child health centre. |

5 extra-visits are offered to all parents. Parents express their will to attend to additional visits |

Mixed-method approaches (interviews, participation rates, review of child records …) |

Study protocol |

Bywater et al, 2018 |

PU |

Does E-SEE Steps enhance child social ?emotional well-being at 20 months when compared with services as usual? |

All intervention parents will receive an Incredible Years Infant book (universal level), and may be offered the Infant and/or Toddler group-based programme/s—?based on parent depression scores on the Patient ?Health Questionnaire or child social emotional well-?being scores on the Ages and Stages Questionnaire: Social Emotional, Second Edition (ASQ:SE-2). Control group parents will receive services as usual. |

Patient Health Questionnaire or child social emotional well-being scores on the Ages and Stages Questionnaire: Social Emotional, Second Edition (ASQ:SE-2). |

Not specified |

Study protocol |

Darquy et al, 2018 |

PU |

Address socio-economic inequalities found in the existing organised programmes for cancer screening, in line with the established priorities ?of the national French Cancer Plan 2014–2019. |

A programme open to all women aged 25–65, with targeted interventions for identified under screened populations (women over 50 yrs, unaware of their risks (precarious or homosexual women), vulnerable populations, women at increased risk of cervical cancer. |

Preliminary studies to quantify non-participating women to the regular, universal screening. |

Not specified |

Study protocol |

Dodge et al, 2019 |

Targeted Universalism |

Description and evaluation of the program “Family Connects” |

Family connect model, based on three pillars: one or more home visits (after child-birth), community alignment (community resources available for families), and data and monitoring (electronic health record shared by all stakeholders). |

Individually, through home-visits |

Two RCT and one field trial (interviews of parents): connectedness, parenting and parent mental health, child health and wellbeing |

Families from interventions groups reported more connections to community resources, more positive parenting behaviours and fewer serious injuries or illnesses among their infants. |

PU, proportionate unversalism

FIGURE 2. Graphical summary of the review.

Theoretical context behind PU

Theoretical concepts behind PU refer to two major concepts: universalism and targeting that are widely developed in the literature, especially in human and social sciences (Table 1). If the notion of universalism dates back to the Age of Enlightenment in Europe, opposition between universalism and targeting as ways to reduce inequalities have been a subject of debate for social and political scientists for the last thirty years and is still current.

In a seminal article, Korpi and Palme described the Paradox of redistribution: a universal policy is more redistributive than a targeted one. They classically opposed the two: a policy is either one or the other (12). Yet, the distinction between both terms is sometimes blurred (13). Further, many researchers have added nuances, suggesting in particular that we should consider the intentions of policies on the one hand and their outputs on the other. For example, a policy may have a universal intention: a family benefits for each child born. But if lower income families concentrate the largest families, then the policy appears targeted in its outputs (e.g., a family with more children will receive more money) (14-16). These researchers therefore advocate to define policies according to their intentions and not to their outputs (16).

Targeting is a complex notion. G. Cruz-Martinez distinguished different forms of targeting: by means or by social category (17). In her glossary, G. Carey defines different forms of targeting, that she called negative and positive selectivisms and particularism. Negative selectivism could be considered as means-testing, which corresponds to the measure of people’s income to decide of the attribution of social assistance. Positive selectivism refers to a targeting based on needs, irrespective ?of a social position; whereas particularism proposes different standards for different categories reflecting diverse circumstances (18).

S. Noy deplored the fact that targeting is often confused with means-testing, which can lead to misinterpretations (19). Those are two related but distinct concepts. Targeting involves focusing on a “particular segment of the population” (status characteristic, location…), whereas means-testing focuses only on income. According to her, “this distinction is important because some criticisms of targeting are actually criticisms of the strictness of enforcement in means-testing, utilized to ensure that only the intended recipients receive benefits” (19).

Many scholars analysed advantages and disadvantages of targeting and universalism (15–17,20–30). Despite a seemingly cost-effective principle, targeting leads to many issues: stigmatisation, increased social distance between recipients and non-recipients, administrative cost for means-testing, and also misclassifications, under-coverages and leakages (20,31,32). On their side, advocates of targeting argued that universal approaches increase inequalities, and involve significant costs for society.

Following theses controversies, in 1991, Théda Skocpol proposed “targeting within universalism”, which combines both approaches, and it is sometimes called “progressive universalism”. She proposed “universal policy frameworks for extra benefits and services that disproportionately help less privileged people without stigmatizing them” (33). In 1985, G. Rose introduced this debate into public health policy (34,31). According to him, health risks are distributed among a “risk continuum”. Thus, he described the prevention paradox as “a preventive measure that brings large benefits to the community offers little to each participating individual.” As the causes of many diseases are related to social determinants of health, G. Rose argued that “medicine and politics should not be kept apart”. Similarly to social scientists, he exposed advantages and disadvantages of population-level versus high-risk strategies in prevention in his book (2,3).

A few years later, Fair Society, Healthy Lives introduced the principle of PU, a means of addressing the dichotomization between universalism and targeting in the health field (3). Based on the theory of the social determinants of health, PU approach proposes to focus on upstream determinants, and from this point of view advocates social policies focusing, for example, on education or employment.

Designing PU interventions and policies: methodological challenges

Despite this rich literature, there are still gaps to address when designing programmes and policies inspired from these principles (18,35). To illustrate these questions, Table 3 details one targeted universalism and one PU application. They both could contribute to target the 3.4 Sustainable Development Goal “By 2030, reduce by one third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases” through the reduction of prevalence of overweight and obesity (36).

TABLE 3. Illustrations of proportionate unversalism and targeted universalism regarding achievement of SDG 3.4 (Specific example: reduction of overweight and obesity).

|

Richmond Health in all policies programme (65) |

PRALIMAP-INES study (64) |

|---|---|---|

Level of application |

Local policy |

Health intervention with a national vocation |

Global description of the policy/intervention |

Implementation of six final HiAP intervention areas - Governance and Leadership, - Economic Development and Education, - Full Service and Safe Communities, - Neighborhood Built Environments, - Environmental Health and Justice, and - Quality and Accessible Health Homes and Social Services. |

1) Identification of social category through a deprivation score 2) Composition of three groups: - one control group (standard care management) for socially advantaged group - two randomized intervention groups among less-advantaged adolescents: one control group and one standard and strengthened care management |

Lever of action |

Upstream determinants |

Downstream determinants |

Objective pursued by authors |

“promoting healthy food store development ?through land-use zoning” (One specific objective ?of the 3rd axis) |

“Evaluate school-based intervention to address social inequalities in adolescents who are overweight and the impact of the interventions on adopting healthy behaviors, quality of life, anxiety and depression.” |

Targeted population |

Population of Richmond and especially from ?less-advantaged areas |

Adolescents from 35 state-run high and middle schools (North-Eastern of France) |

Universal part of the policy/intervention |

“General health equity goals for the city” |

Standard-care management (5 collective educational sessions) |

Targeted part of the policy/intervention |

Populations and places to help specific, currently vulnerable groups and neighbourhoods get healthier |

Strengthened-care management intending to address barriers was proposed for only socially less-advantaged adolescents: - 3 multidisciplinary (school medical doctors and nurses; dieticians, psychologists etc.) meetings; - combination of different targeted activities: food workshops, peer health promotion, sporting good coupon (40€), hospital specialized management of obesity, physical activity motivational interviewing and motivational interviewing. |

Evaluation of the level of disadvantage |

Through identification of key-drivers of ?inequalities |

Family affluence Scale (5 social categories) |

Evaluation criteria(on) of health improvement |

% Report eating fruit/veggies 3+ day last week ?% Adults engaged in regular physical activity in ?last week ?% Reporting poor health (self-reported health) |

Comparison of the BMI after intervention among three groups constituted according to Family Affluence Scale score |

HiAP, Health in all policies; BMI, body mass index

Context and level of actions

Literature showed different applications and interpretations of PU principle, notably regarding the variety of thematic areas covered: cancer screening (n=5), maternal and child health (n=9), child health and poverty (n=4), etc. (Table 1).

The level of actions in which PU can apply as a principle were also heterogeneous in the literature. Different authors propose it as a principle to conceive public health policies at national or regional levels such as alcohol prevention policies, cancer screening, or more individualized interventions such as home visiting programmes (37-41). Carey et al. proposed a framework based on the subsidiarity principle which argues that to flatten the social gradient, mixed scales of interventions should occur (42). She insists on the fact that all health interventions should be integrated into a broader landscape to reach such objectives. This is a systemic vision of PU, which Porcherie et al. also proposed (43). Whatever the level of action, national programs should be coherent and in interaction with local ones (28,44). Different levels of PU implementation (micro, meso or macro) are not mutually exclusive, and combining them allows expecting more efficient results (45).

Pursued objectives

The objectives of actions following PU should be both to increase overall health population and to flatten the social gradient (46). In the majority of interventions included in the review, authors stated aiming at reducing health inequality, target access or geographical inequalities but not flattening directly the social gradient (Table 2) (37,38,47–53). Reviews included also did not identify interventions following this objective ?(54-56). Welsh et al., in a review to identify interventions promoting wellbeing or prevent mental illness, alleged that “very few interventions [were] specifically designed to address inequities or evaluated in regard to differential impact” (42).

Different interpretations of proportionate universalism

PU definition could lead to different interpretations in practice. Dierckx, in her evaluation of three cases of child and family social work places highlighted that field workers disagreed on the definition of PU (57).

Moreover, interpretation of the notion of proportionate intensity of the delivered health action is heterogeneous in the literature. Does it have to be the same intervention in different intensities like a social allowance increasing when need increases (17)? Or different interventions for different target groups (58,59)? Alternatively, should the notion of proportion be understood in a context of a policy that will more apply on disadvantaged categories of population (e.g., the Minimum Price Unit for alcohol or taxes on sugary drinks) (39,45)? Indeed, such legal and regulatory interventions are universal by nature, and as consumption has been proven to also follow a gradient, effect would be then naturally tailored. This question echoes the one raised by social scientists regarding the difference between intentions, outputs and outcomes of a policy.

Benach et al. introduced categories of “universal policy with additional focus on gap” and “redistributive policy” as scenarii close to but different from PU (60). PU consists in approach where “the benefit increases through the gradient and the gap between socio-economic groups is reduced” (60). In our review, most of interventions were either home visiting and then by nature PU because they are almost individual care, either a sum of actions targeting the most deprived (45,61). Even if they were proportionate most of them were not universal but specifically implemented in deprived area (37,50,62).

Following this proportionality issue, the question of a threshold has also emerged. Indeed, the most proportionate action would by its very nature, be individual, which is not possible to perform for evident feasibility stakes. Then when the type of inequality is targeted, which threshold and which granularity should be applied along the gradient (18)? Indeed, even a ?proportionate targeting implies setting a “poverty line” just above which people will receive less and may perceive it as unfair (63). In some interviews, Thomson et al. questioned women’s experiences of antenatal care services and they found out that “for women with low-risk pregnancies, there was felt to be some inequity in service provision” (35).

To adapt interventions in proportion to the level of disadvantage or need, it is necessary to determine what the needs could be. This question refers to the matter of upstream or downstream determinants interventions intend to address (59). Among the interventions included in our review, some targeted upstream determinants (neighbourhood renewal, parenting), others downstream (cancer screening, obesity care management) (50,64). When downstream determinants are the lever of action, authors targeted more easily access to care or health risk (48,51). For upstream determinants, evaluation of needs can be performed according to income, socio-economic index or scores, social category or territorial category. One example of targeting upstream determinants could be the implementation of “health in all policies”, which means applying policies not directly aiming at increasing health such as environmental or educational policies, but with indirect intended effects on health. Richmond City, California, settled a new framework based on this principle, referring to targeted universalism and participative democracy (Table 3) (65). Once the need has been determined, the next step is to ensure that no misclassifications occurred. Brewster et al. tested different techniques of health-risk measurements to determine if a targeted intervention reached its target (53). They found out that almost 50% of the children targeted with their postal code (selection of most deprived areas) were indeed not at-risk according to other measurements (clinical antecedents, other indexes of deprivation) (53). According to Cornia and Stewart, two types of targeting errors could occur: exclusion, when an intervention fails to identify people in need, and inclusion, when the intervention identifies wrong people (63,66). Another focus point lies in the fact that people who are entitled to some aid do not necessarily use it, mostly because they do not know that they are entitled to it; there is a major communication issue at stake (67). Thus, performing evaluation of needs is very important to ensure that intervention will reach its objectives (68).

This notion is also in line with that of needs assessment through means (income) or needs testing described above (42). Carey et al. stated that PU should apply positive selectivism (i.e., through needs and not means evaluation), notably because previous experiences of means-testing, performed in Anglo-Saxon countries showed worse results in terms of equity (69).

Ethical and evaluation challenges

Some papers addressed ethical problems through targeting some more in-need populations (48,63,70–72). In this context, stigmatization is one of the most encountered problem and must be avoided. For example, qualitative studies conducted with mothers in the context of home visiting interventions have revealed a feeling of guilt felt by mothers, and sometimes a judgmental attitude from professionals against them (73). Finally, Bekken and Dierckx stressed the ethical need to investigate what healthcare and social workers know about these concepts (57,74).

Many scholars highlighted difficulties to properly evaluate health inequalities reduction and much more the reduction of the social gradient (20,15,27,75,59). Analysis are often limited to aggregated level, and evaluate more redistributive outputs than intentions (14). A solution has been proposed by Richmond city, which developed quantitative indicators to evaluate impact of its “health in all policies” program and give to the city council performance goals to reach, expressed through indicators such as percentage of residents not experiencing racism, percentage of city employees who are women and/or minorities…(65).

Discussion

The main objective of our scoping review was to map available scientific literature on PU and its related concepts. We described theoretical foundations behind PU, and mainly social theories such as the Paradox Redistribution or Targeting within Universalism proposed in the last 40 years. Analyses of ins and outs of these theories permitted to better understand practical issues raised by PU (or its related concepts) applications. How to implement proportionate interventions? Which threshold to apply when identifying level of disadvantage? Which indicator should be used to define level of disadvantage? How to demonstrate effective reduction of social gradient of health?

Analysis of PU applications provided in this review responded to some of these questions but some are methodological challenges to address in further research.

It appears that the precise and practical definition of the principle is not consensual and may lead to different interpretations (45). Indeed, interventions referring to PU were rare and did not always fully comply with the principle: they were only targeted (not universal) or authors did not consider reduction of inequalities as an outcome.

All the questions raised by human and social scientists regarding universalism or targeting theories can be applied to public health context and PU applications. Through the description of PU applications, more specific issues related to PU interventions design and evaluation have been highlighted (Figure 2 and Table 3).

In particular, the proportionate attribution of a policy raised many practical issues (identification of needs, exact proportionality to the gradient...), but the universal aspect should not be forgotten. Indeed, when considering how to reduce health inequality, all too often, the most at-risk populations are targeted from the outset (56). It should also be very interesting to explore knowledge and perceptions of front-line professionals and citizens on these issues more deeply (74). A whole literature is emerging in order to understand their knowledge and involve them actively in the reduction of social inequalities (76-79).

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first literature review focusing on PU. This scoping review followed last recommendations and double selection by two authors reduced the risk of misclassifications. We have chosen only a few key words synonymous with PU, which does not guarantee the comprehensiveness. However, our objective was not to be exhaustive but to identify the authors who recognize themselves in this term from a public health perspective. Moreover, the majority of included papers concerned European countries (n=39) where Welfare States are prevalent and PU originated. Even with related concepts, we found very few Australian, American or Asian interventions referring to PU. This does not mean that these concepts are not used, but rather that researchers from these countries probably refer to other concepts or do not name it with the synonyms we used. It should be further investigated. In the same way, we choose not to focus on grey literature, to apprehend researcher’s insights on PU. Yet a rapid research with the keyword PU reveals a few references to the PU principle from European local health authorities (Marmot Cities for example), which have applied the principle and cite it. Here again, it would be very valuable to interview them and evaluate their representations of PU.

Upstream and downstream determinants

The term PU was proposed besides six policy objectives: Give every child the best start in life — Enable all children, young people and adults to maximise their capabilities and have control over their lives — Create fair employment and good work for all — Ensure healthy standard of living for all — Create and develop healthy and sustainable places and communities — Strengthen the role and impact of ill health prevention (3). PU was therefore proposed as a means of implementing upstream policies, aiming at addressing the root causes of inequalities.

From this perspective, the results of our review show an entirely different reality: except for parenting interventions, the majority of papers directly referring to PU described interventions targeting downstream determinants to increase access to prevention or care (32,35,36,39).

This is not necessarily contradictory; all these interventions, both upstream and downstream, can be seen as complementary actions acting at different levels, addressing the problems at the root, as well as the negative consequences of a lack of action at a more proximal level.

Many public health interventions included in our review have applied PU to address problems of access to care, or downstream determinants. This can also be explained by the fact that public health interventions, when effective, have been shown to widen health inequalities (80).

Conversely, the relatively low number of medico-economic articles found in the review indicates that economists, although very familiar with the issues of universalism and targeting, have referred much less to the PU principle. Yet studies evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of redistributive policies in reducing health inequalities are legion (81-83). Indeed, it is not an easy task to distinguish PU approach from the more classically “distributional” approaches that evaluate an intervention, a program, a policy, against distributional objectives (e.g., to give greater weight to increasing the screening rate of disadvantaged populations because they have a low screening rate). In the light of these elements, it appears essential to initiate a multidisciplinary dialogue in order to achieve a holistic approach of PU.

Conclusion

This review allowed us to map available scientific literature on PU and its related concepts. PU principle originates from social theories: Targeting within universalism, Paradox of redistribution. As highlighted by authors who implemented PU interventions, application raises many challenges from design to evaluation. Analysis of PU applications provided in this review answered to some of them but remaining methodological challenges could be addressed in further research.

Disclaimer.

Authors hold sole responsibility for the views expressed in the manuscript, which may not necessarily reflect the opinion or policy of the RPSP/PAJPH and/or PAHO.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions.

FA contributed to the conception and design of the work, to the selection and analysis of included articles, and revised substantially the content of the paper. MM, LC and JW contributed to the conception and design of the work and revised substantially the content of the paper. FFO contributed to the conception and design of the work, to the selection and analysis of included articles and drafted the paper.

Conflict of interests.

None declared.

References

- 1.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Public Health. 2005;365:6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 1. Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Public Health. 2005;365:6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.The Final Report of the Commission of the Pan American Health Organisation on Equity and Health Inequalities in the Americas [Internet] [[cited 19 July 2020]]. Available at: http://www.?instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/the-final-report-?of-the-commission-of-the-pan-american-health-organisation-?on-equity-and-health-inequalities-in-the-americas.; 2. The Final Report of the Commission of the Pan American Health Organisation on Equity and Health Inequalities in the Americas [Internet]. [cited 19 July 2020]. Available at: http://www.?instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/the-final-report-?of-the-commission-of-the-pan-american-health-organisation-?on-equity-and-health-inequalities-in-the-americas

- 3.Fair Society Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review) [Internet] Institute of Health Equity. [[cited 30 May 2018]]. Available at: http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-?society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review.; 3. Fair Society Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review) [Internet]. Institute of Health Equity. [cited 30 May 2018]. Available at: http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-?society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review

- 4.Chandra A, Vogl TS. Rising up with shoe leather? A comment on Fair Society, Healthy Lives (the Marmot Review) Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(7):1227–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 4. Chandra A, Vogl TS. Rising up with shoe leather? A comment on Fair Society, Healthy Lives (the Marmot Review). Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(7):1227-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Canning D, Bowser D. Investing in health to improve the wellbeing of the disadvantaged: Reversing the argument of Fair Society, Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review) Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(7):1223–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 5. Canning D, Bowser D. Investing in health to improve the wellbeing of the disadvantaged: Reversing the argument of Fair Society, Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review). Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(7):1223-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Subramanyam MA, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Reactions to Fair Society, Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review) Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(7):1221–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 6. Subramanyam MA, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Reactions to Fair Society, Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review). Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(7):1221-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.11.1.1 Why a scoping review? - JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - JBI GLOBAL WIKI [Internet] [[cited 10 July 2020]]. Available at: https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=3178748.; 7. 11.1.1 Why a scoping review? - JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis - JBI GLOBAL WIKI [Internet]. [cited 10 July 2020]. Available at: https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=3178748

- 8.Kastner M, Tricco AC, Soobiah C, Lillie E, Perrier L, Horsley T, et al. What is the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to conduct a review? Protocol for a scoping review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 8. Kastner M, Tricco AC, Soobiah C, Lillie E, Perrier L, Horsley T, ?et al. What is the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to conduct a review? Protocol for a scoping review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]; 9. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32.

- 10.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 10. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 11. Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Korpi W, Palme J. The Paradox of Redistribution and Strategies of Equality: Welfare State Institutions, Inequality, and Poverty in the Western Countries. Am Sociol Rev. 1998;63(5):661–687. [Google Scholar]; 12. Korpi W, Palme J. The Paradox of Redistribution and Strategies of Equality: Welfare State Institutions, Inequality, and Poverty in the Western Countries. Am Sociol Rev. 1998;63(5):661-87.

- 13.Grogan CM, Patashnik EM. Universalism within Targeting: Nursing Home Care, the Middle Class, and the Politics of the Medicaid Program. Soc Serv Rev. 2003;77(1):51–71. [Google Scholar]; 13. Grogan CM, Patashnik EM. Universalism within Targeting: Nursing Home Care, the Middle Class, and the Politics of the Medicaid Program. Soc Serv Rev. 2003;77(1):51-71.

- 14.Van Lancker W, Van Mechelen N. Universalism under siege? Exploring the association between targeting, child benefits and child poverty across 26 countries. Soc Sci Res. 2015;50:60–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 14. Van Lancker W, Van Mechelen N. Universalism under siege? Exploring the association between targeting, child benefits and child poverty across 26 countries. Soc Sci Res. 2015;50:60-75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Marchal S, Van Lancker W. The Measurement of Targeting Design in Complex Welfare States: A Proposal and Empirical Applications. Soc Indic Res. 2019;143(2):693–726. [Google Scholar]; 15. Marchal S, Van Lancker W. The Measurement of Targeting Design in Complex Welfare States: A Proposal and Empirical Applications. Soc Indic Res. 2019;143(2):693-726.

- 16.Jacques O, Noël A. The case for welfare state universalism, or the lasting relevance of the paradox of redistribution. J Eur Soc Policy. 2018;28(1):70–85. [Google Scholar]; 16. Jacques O, Noël A. The case for welfare state universalism, or the lasting relevance of the paradox of redistribution. J Eur Soc Policy. 2018;28(1):70-85.

- 17.Cruz-Martínez G. Older-Age Social Pensions and Poverty: Revisiting Assumptions on Targeting and Universalism. Poverty Public Policy. 2019;11(1-2):31–56. [Google Scholar]; 17. Cruz-Martínez G. Older-Age Social Pensions and Poverty: Revisiting Assumptions on Targeting and Universalism. Poverty Public Policy. 2019;11(1-2):31-56.

- 18.Carey G, Crammond B. A glossary of policy frameworks: the many forms of « universalism » and policy « targeting ». J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(3):303–307. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 18. Carey G, Crammond B. A glossary of policy frameworks: the many forms of « universalism » and policy « targeting ». J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(3):303-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Noy S. Healthy targets? World Bank projects and targeted health programmes and policies in Costa Rica, Argentina, and Peru, 1980–2005. Oxf Dev Stud. 2018;46(2):164–183. [Google Scholar]; 19. Noy S. Healthy targets? World Bank projects and targeted health programmes and policies in Costa Rica, Argentina, and Peru, 1980–2005. Oxf Dev Stud. 2018;46(2):164-83.

- 20.Fischer AM. Towards Genuine Universalism within Contemporary Development Policy. IDS Bull. 2010;41(1):36–44. [Google Scholar]; 20. Fischer AM. Towards Genuine Universalism within Contemporary Development Policy. IDS Bull. 2010;41(1):36-44.

- 21.Brady D, Burroway R. Targeting, Universalism, and Single-Mother Poverty: A Multilevel Analysis Across 18 Affluent Democracies. Demography. 2012;49(2):719–746. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0094-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 21. Brady D, Burroway R. Targeting, Universalism, and Single-Mother Poverty: A Multilevel Analysis Across 18 Affluent Democracies. Demography. 2012;49(2):719-46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Kuivalainen S, Niemelä M. From universalism to selectivism: the ideational turn of the anti-poverty policies in Finland. J Eur Soc Policy. 2010;20(3):263–276. [Google Scholar]; 22. Kuivalainen S, Niemelä M. From universalism to selectivism: the ideational turn of the anti-poverty policies in Finland. J Eur Soc Policy. 2010;20(3):263-76.

- 23.Imai K. Targeting versus universalism: An evaluation of indirect effects of the Employment Guarantee Scheme in India. J Policy Model. 2007;29(1):99–113. [Google Scholar]; 23. Imai K. Targeting versus universalism: An evaluation of indirect effects of the Employment Guarantee Scheme in India. J Policy Model. 2007;29(1):99-113.

- 24.Müller K. Contested universalism: from Bonosol to Renta Dignidad in Bolivia. Int J Soc Welf. 2009;18(2):163–172. [Google Scholar]; 24. Müller K. Contested universalism: from Bonosol to Renta Dignidad in Bolivia. Int J Soc Welf. 2009;18(2):163-72.

- 25.Kim T. The welfare state as an institutional process. Soc Sci J. 2010;47(3):492–507. [Google Scholar]; 25. Kim T. The welfare state as an institutional process. Soc Sci J. 2010;47(3):492-507.

- 26.Lau MK-W, Chou K-L. Targeting, Universalism and Child Poverty in Hong Kong. Child Indic Res. 2019;12(1):255–275. [Google Scholar]; 26. Lau MK-W, Chou K-L. Targeting, Universalism and Child Poverty in Hong Kong. Child Indic Res. 2019;12(1):255-75.

- 27.Lancker WV, Ghysels J, Cantillon B. The impact of child benefits on single mother poverty: Exploring the role of targeting in 15 European countries. Int J Soc Welf. 2015;24(3):210–222. [Google Scholar]; 27. Lancker WV, Ghysels J, Cantillon B. The impact of child benefits on single mother poverty: Exploring the role of targeting in 15 European countries. Int J Soc Welf. 2015;24(3):210-22.

- 28.Brady D, Bostic A. Paradoxes of social policy: Welfare transfers, relative poverty and redistribution preferences [Internet] LIS Cross-National Data Center in Luxembourg. 2014. Nov, [[cited 17 Feb 2020]]. Report No.: 624. Available at: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/lisliswps/624.htm.; 28. Brady D, Bostic A. Paradoxes of social policy: Welfare transfers, relative poverty and redistribution preferences [Internet]. LIS Cross-National Data Center in Luxembourg; 2014 nov [cited 17 Feb 2020]. Report No.: 624. Available at: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/lisliswps/624.htm

- 29.Kabeer N. The Politics and Practicalities of Universalism: Towards a Citizen-Centred Perspective on Social Protection. Eur J Dev Res. 2014;26(3):338–354. [Google Scholar]; 29. Kabeer N. The Politics and Practicalities of Universalism: Towards a Citizen-Centred Perspective on Social Protection. Eur J Dev Res. 2014;26(3):338-54.

- 30.Neelsen S, O’Donnell O. Progressive universalism? The impact of targeted coverage on health care access and expenditures in Peru. Health Econ. 2017;26(12):e179–e203. doi: 10.1002/hec.3492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 30. Neelsen S, O’Donnell O. Progressive universalism? The impact of targeted coverage on health care access and expenditures in Peru. Health Econ. 2017;26(12):e179-203. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.McLaren L. In defense of a population-level approach to prevention: why public health matters today. Can J Public Health. 2019;110(3):279–284. doi: 10.17269/s41997-019-00198-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 31. McLaren L. In defense of a population-level approach to prevention: why public health matters today. Can J Public Health. 2019;110(3):279-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Horton T, Gregory J. Why Solidarity Matters: The Political Strategy of Welfare Design. Polit Q. 2010;81(2):270–276. [Google Scholar]; 32. Horton T, Gregory J. Why Solidarity Matters: The Political Strategy of Welfare Design. Polit Q. 2010;81(2):270-6.

- 33.Skocpol T. Washington DC: The Brookings Institution; 1991. The Urban Underclass. [Google Scholar]; 33. Skocpol T. The Urban Underclass. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution; 1991.

- 34.Rose G, Khaw K-T, Marmot M. Rose’s Strategy of Preventive Medicine. Oxford University Press; 2008. [[cited 3 March 2020]]. Rose’s Strategy of Preventive Medicine [Internet] Available at: https://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/?9780192630971.001.0001/acprof-9780192630971. [Google Scholar]; 34. Rose G, Khaw K-T, Marmot M. Rose’s Strategy of Preventive Medicine [Internet]. Rose’s Strategy of Preventive Medicine. Oxford University Press; 2008 [cited 3 March 2020]. Available at: https://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/?9780192630971.001.0001/acprof-9780192630971

- 35.Thomson G, Dykes F, Singh G, Cawley L, Dey P. A public health perspective of women’s experiences of antenatal care: An exploration of insights from a community consultation. Midwifery. 2013;29(3):211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 35. Thomson G, Dykes F, Singh G, Cawley L, Dey P. A public health perspective of women’s experiences of antenatal care: An exploration of insights from a community consultation. Midwifery. 2013;29(3):211-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.3.4 by 2030 reduce by one-third pre-mature mortality from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) through prevention and treatment, and promote mental health and wellbeing – Indicators and a Monitoring Framework [Internet] [[cited 19 July 2020]]. Available at: https://indicators.report/targets/3-4/; 36. 3.4 by 2030 reduce by one-third pre-mature mortality from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) through prevention and treatment, and promote mental health and wellbeing – Indicators and a Monitoring Framework [Internet]. [cited 19 July 2020]. Available at: https://indicators.report/targets/3-4/

- 37.Burström B, Marttila A, Kulane A, Lindberg L, Burström K. Practising proportionate universalism – a study protocol of an extended postnatal home visiting programme in a disadvantaged area in Stockholm, Sweden. [[cited 17 Sept 2019]];BMC Health Serv Res [Internet] 2017 17(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2038-1. Available at: http://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-017-2038-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 37. Burström B, Marttila A, Kulane A, Lindberg L, Burström K. Practising proportionate universalism – a study protocol of an extended postnatal home visiting programme in a disadvantaged area in Stockholm, Sweden. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2017;17(1). [cited 17 Sept 2019] Available at: http://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-017-2038-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Guillaume E, Launay L, Dejardin O, Bouvier V, Guittet L, Déan P, et al. Could mobile mammography reduce social and geographic inequalities in breast cancer screening participation? Prev Med. 2017;100:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 38. Guillaume E, Launay L, Dejardin O, Bouvier V, Guittet L, Déan P, et al. Could mobile mammography reduce social and geographic inequalities in breast cancer screening participation? Prev Med. 2017;100:84-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Rice P. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose: a Review of Recent Alcohol Policy Developments in Europe. Alcohol Alcohol. 2019;54(2):123–127. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agz013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 39. Rice P. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose: a Review of Recent Alcohol Policy Developments in Europe. Alcohol Alcohol. 2019;54(2):123-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Dodge KA, Goodman WB. Universal Reach at Birth: Family Connects. Future Child. 2019;29(1):41–60. doi: 10.1353/foc.2019.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 40. Dodge KA, Goodman WB. Universal Reach at Birth: Family Connects. Future Child. 2019;29(1):41-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Van Vliet J. How to apply the evidence-based recommendations for greater health equity into policymaking and action at the local level? Scand J Public Health. 2018;46(22_suppl):28–36. doi: 10.1177/1403494818765703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 41. Van Vliet J. How to apply the evidence-based recommendations for greater health equity into policymaking and action at the local level? Scand J Public Health. 2018;46(22_suppl):28-36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Carey G, Crammond B, De Leeuw E. Towards health equity: a framework for the application of proportionate universalism. [[cited 21 mai 2018]];Int J Equity Health [Internet] 2015 14(1) doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0207-6. Available at: http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/14/1/81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 42. Carey G, Crammond B, De Leeuw E. Towards health equity: a framework for the application of proportionate universalism. Int J Equity Health [Internet]. 2015;14(1). [cited 21 mai 2018] Available at: http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/14/1/81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Porcherie M, Le Bihan-Youinou B, Pommier J. À quelle échelle appliquer l’approche universelle proportionnée pour lutter contre les inégalités sociales de santé? Pour une approche contextualisée des actions de prévention et de promotion de la santé. Santé Publique. 2018;S2:25. doi: 10.3917/spub.184.0025. HS2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 43. Porcherie M, Le Bihan-Youinou B, Pommier J. À quelle échelle appliquer l’approche universelle proportionnée pour lutter contre les inégalités sociales de santé?? Pour une approche contextualisée des actions de prévention et de promotion de la santé. Santé Publique. 2018;S2(HS2):25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Affeltranger B, Potvin L, Ferron C, Vandewalle H, Vallée A. Universalisme proportionné?: vers une «?égalité réelle?» de la prévention en France? Santé Publique. 2018;S2:13. doi: 10.3917/spub.184.0013. HS2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 44. Affeltranger B, Potvin L, Ferron C, Vandewalle H, Vallée A. Universalisme proportionné?: vers une «?égalité réelle?» de la prévention en France? Santé Publique. 2018;S2(HS2):13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Carey G, Crammond B, De Leeuw E. Towards health equity: a framework for the application of proportionate universalism. [[cited 17 sept 2019]];Int J Equity Health [Internet] 2015 14(1) doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0207-6. Available at: http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/14/1/81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 45. Carey G, Crammond B, De Leeuw E. Towards health equity: a framework for the application of proportionate universalism. Int J Equity Health [Internet]. 2015;14(1). [cited 17 sept 2019] Available at: http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/14/1/81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Benach J, Malmusi D, Yasui Y, Martínez JM. A new typology of policies to tackle health inequalities and scenarios of impact based on Rose’s population approach. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(3):286–291. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 46. Benach J, Malmusi D, Yasui Y, Martínez JM. A new typology of policies to tackle health inequalities and scenarios of impact based on Rose’s population approach. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(3):286-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Maharaj V, Rahman F, Adamson L. Tackling child health inequalities due to deprivation: using health equity audit to improve and monitor access to a community paediatric service: Tackling child heath inequalities. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40(2):223–230. doi: 10.1111/cch.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 47. Maharaj V, Rahman F, Adamson L. Tackling child health inequalities due to deprivation: using health equity audit to improve and monitor access to a community paediatric service: Tackling child heath inequalities. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40(2):223-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Darquy S, Moutel G, Jullian O, Barré S, Duchange N. Towards equity in organised cancer screening: the case of cervical cancer screening in France. [[cited 17 sept 2019]];BMC Womens Health [Internet] 2018 18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0683-0. Available at: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-018-0683-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 48. Darquy S, Moutel G, Jullian O, Barré S, Duchange N. Towards ?equity in organised cancer screening: the case of cervical cancer screening in France. BMC Womens Health. [Internet]. 2018;18(1). [cited 17 sept 2019] Available at: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-018-0683-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Egan M, Kearns A, Katikireddi SV, Curl A, Lawson K, Tannahill C. Proportionate universalism in practice? A quasi-experimental ?study (GoWell) of a UK neighbourhood renewal programme’s impact on health inequalities. Soc Sci Med. 2016;152:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 49. Egan M, Kearns A, Katikireddi SV, Curl A, Lawson K, Tannahill C. Proportionate universalism in practice? A quasi-experimental ?study (GoWell) of a UK neighbourhood renewal programme’s impact on health inequalities. Soc Sci Med. 2016;152:41-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Legrand K, Lecomte E, Langlois J, Muller L, Saez L, Quinet M-H, et al. Reducing social inequalities in access to overweight and obesity care management for adolescents: The PRALIMAP-INÈS trial protocol and inclusion data analysis. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2017;7:141–157. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 50. Legrand K, Lecomte E, Langlois J, Muller L, Saez L, Quinet M-H, ?et al. Reducing social inequalities in access to overweight and obesity care management for adolescents: The PRALIMAP-INÈS trial protocol and inclusion data analysis. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2017;7:141-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Guillaume E, Dejardin O, Bouvier V, De Mil R, Berchi C, Pornet C, et al. Patient navigation to reduce social inequalities in colorectal cancer screening participation: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2017;103:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 51. Guillaume E, Dejardin O, Bouvier V, De Mil R, Berchi C, Pornet C, ?et al. Patient navigation to reduce social inequalities in colorectal cancer screening participation: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2017;103:76-83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Bywater T, Berry V, Blower SL, Cohen J, Gridley N, Kiernan K, et al. Enhancing Social-Emotional Health and Wellbeing in the Early Years (E-SEE): a study protocol of a community-based randomised controlled trial with process and economic evaluations of the incredible years infant and toddler parenting programmes, delivered in a proportionate universal model. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e026906. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 52. Bywater T, Berry V, Blower SL, Cohen J, Gridley N, Kiernan K, et al. Enhancing Social-Emotional Health and Wellbeing in the Early Years (E-SEE): a study protocol of a community-based randomised controlled trial with process and economic evaluations of the incredible years infant and toddler parenting programmes, delivered in a proportionate universal model. BMJ Open. 2018:8:e026906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Brewster L, Sherriff A, Macpherson L. Effectiveness and reach of a directed-population approach to improving dental health and reducing inequalities: a cross sectional study. [[cited 17 Sept 2019]];BMC Public Health [Internet] 2013 13(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-778. Available at: http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 53. Brewster L, Sherriff A, Macpherson L. Effectiveness and reach of a directed-population approach to improving dental health and reducing inequalities: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2013;13(1). [cited 17 Sept 2019] Available at: http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Cowley S, Whittaker K, Malone M, Donetto S, Grigulis A, Maben J. Why health visiting? Examining the potential public health benefits from health visiting practice within a universal service: A narrative review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(1):465–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 54. Cowley S, Whittaker K, Malone M, Donetto S, Grigulis A, Maben J. Why health visiting? Examining the potential public health benefits from health visiting practice within a universal service: A narrative review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(1):465-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Welsh J, Strazdins L, Ford L, Friel S, O’Rourke K, Carbone S, et al. Promoting equity in the mental wellbeing of children and young people: a scoping review. Health Promot Int. 2015;30(suppl 2):ii36–ii76. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 55. Welsh J, Strazdins L, Ford L, Friel S, O’Rourke K, Carbone S, et al. Promoting equity in the mental wellbeing of children and young people: a scoping review. Health Promot Int. 2015;30(suppl 2):ii36-76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Morrison J, Pikhart H, Ruiz M, Goldblatt P. Systematic review of parenting interventions in European countries aiming to reduce social inequalities in children’s health and development. [[cited 17 Sept 2019]];BMC Public Health [Internet] 2014 14(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1040. Available at: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/?1471-2458-14-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 56. Morrison J, Pikhart H, Ruiz M, Goldblatt P. Systematic review of parenting interventions in European countries aiming to reduce social inequalities in children’s health and development. BMC Public Health. [Internet]. 2014;14(1). [cited 17 Sept 2019] Available at: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/?1471-2458-14-1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Dierckx M, Devlieghere J, Vandenbroeck M. Proportionate universalism in child and family social work. [[cited 27 Feb 2020]];Child Fam Soc Work [Internet] 2020 25:337–344. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/cfs.12689. [Google Scholar]; 57. Dierckx M, Devlieghere J, Vandenbroeck M. Proportionate universalism in child and family social work. Child Fam Soc Work. [Internet]. 2020;25:337-344. [cited 27 Feb 2020] Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/cfs.12689

- 58.Darquy S, Moutel G, Jullian O, Barré S, Duchange N. Towards equity in organised cancer screening: the case of cervical cancer screening in France. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:192. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0683-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 58. Darquy S, Moutel G, Jullian O, Barré S and Duchange N. Towards equity in organised cancer screening: the case of cervical cancer screening in France. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Goldblatt P. How Can a Global Social Support System Hope to Achieve Fairer Competiveness? Comment on « A Global Social Support System: What the International Community Could Learn From the United States’ National Basketball Association ». Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;5(3):205–206. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 59. Goldblatt P. How Can a Global Social Support System Hope to Achieve Fairer Competiveness? Comment on « A Global Social Support System: What the International Community Could Learn From the United States’ National Basketball Association ». Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;5(3):205-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Benach J, Malmusi D, Yasui Y, Martínez JM. A new typology of policies to tackle health inequalities and scenarios of impact based on Rose’s population approach. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(3):286–291. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 60. enach J, Malmusi D, Yasui Y, Martínez JM. A new typology of policies to tackle health inequalities and scenarios of impact based on Rose’s population approach. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(3):286-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Barlow J, McMillan AS, Kirkpatrick S, Ghate D, Barnes J, Smith M. Health-Led Interventions in the Early Years to Enhance Infant and Maternal Mental Health: A Review of Reviews. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2010;(4):178. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2010.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 61. Barlow J, McMillan AS, Kirkpatrick S, Ghate D, Barnes J, Smith M. Health-Led Interventions in the Early Years to Enhance Infant and Maternal Mental Health: A Review of Reviews. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2010;(4):178. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Barboza M, Kulane A, Burström B, Marttila A. A better start for health equity? Qualitative content analysis of implementation of extended postnatal home visiting in a disadvantaged area in Sweden. [[cited 17 sept 2019]];Int J Equity Health [Internet] 2018 17(1) doi: 10.1186/s12939-018-0756-6. Available at: https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/?10.1186/s12939-018-0756-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 62. Barboza M, Kulane A, Burström B, Marttila A. A better start for health equity? Qualitative content analysis of implementation of extended postnatal home visiting in a disadvantaged area in Sweden. Int J Equity Health [Internet]. 2018;17(1). [cited 17 sept 2019] Available at: https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/?10.1186/s12939-018-0756-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Devereux S. Is targeting ethical? Glob Soc Policy Interdiscip J Public Policy Soc Dev. 2016;16(2):166–181. [Google Scholar]; 63. Devereux S. Is targeting ethical? Glob Soc Policy Interdiscip J Public Policy Soc Dev. 2016;16(2):166-81.

- 64.Briançon S, Legrand K, Muller L, Langlois J, Saez L, Spitz E, et al. Effectiveness of a socially adapted intervention in reducing social inequalities in adolescence weight. The PRALIMAP-INÈS school-based mixed trial. Int J Obes. 2020;44(4):895–907. doi: 10.1038/s41366-020-0520-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 64. Briançon S, Legrand K, Muller L, Langlois J, Saez L, Spitz E, et al. Effectiveness of a socially adapted intervention in reducing social inequalities in adolescence weight. The PRALIMAP-INÈS school-based mixed trial. Int J Obes. 2020;44(4):895-907. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Corburn J, Curl S, Arredondo G, Malagon J. Health in All Urban Policy: City Services through the Prism of Health. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2014;91(4):623–636. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9886-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 65. Corburn J, Curl S, Arredondo G, Malagon J. Health in All Urban Policy: City Services through the Prism of Health. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2014;91(4):623-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Cornia GA, Stewart F. Two errors of targeting. J Int Dev. 1993;5(5):459–496. [Google Scholar]; 66. Cornia GA, Stewart F. Two errors of targeting. J Int Dev. 1993;5(5):459-96.

- 67.Moffatt S, Higgs P. Charity or Entitlement? Generational Habitus and the Welfare State among Older People in North-east England. Soc Policy Adm. 2007;41(5):449–464. [Google Scholar]; 67. Moffatt S, Higgs P. Charity or Entitlement? Generational Habitus and the Welfare State among Older People in North-east England. Soc Policy Adm. 2007;41(5):449-64.

- 68.Sannino N, Biga J, Kurth T, Picon E. Quand l’universalisme proportionné devient relatif?: l’accès aux soins des travailleurs non-salariés. Santé Publique. 2018;S2:165. doi: 10.3917/spub.184.0165. HS2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 68. Sannino N, Biga J, Kurth T, Picon E. Quand l’universalisme proportionné devient relatif?: l’accès aux soins des travailleurs non-salariés. Santé Publique. 2018;S2(HS2):165. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Green K. Response: Means-testing child benefits will hit the poor, not the rich. The Guardian [Internet] Sep 29, 2009. [[cited 18 Sept 2019]]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/?2009/?sep/30/means-testing-benefits-hits-poor.; 69. Green K. Response: Means-testing child benefits will hit the poor, not the rich. The Guardian [Internet]. 29 sept 2009 [cited 18 Sept 2019]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/?2009/?sep/30/means-testing-benefits-hits-poor

- 70.Vitus K, Tørslev MK, Ditlevsen K, Nielsen AL. Body weight management and dilemmas of health responsibility for vulnerable groups in the changing Danish welfare state: a comparative case analysis. Crit Public Health. 2018;28(1):22–34. [Google Scholar]; 70. Vitus K, Tørslev MK, Ditlevsen K, Nielsen AL. Body weight management and dilemmas of health responsibility for vulnerable groups in the changing Danish welfare state: a comparative case analysis. Crit Public Health. 2018;28(1):22-34.

- 71.Moutel G, Duchange N, Lièvre A, Orgerie MB, Jullian O, Sancho-Garnier H, et al. Low participation in organized colorectal cancer screening in France: underlying ethical issues. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2019;28(1):27–32. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 71. Moutel G, Duchange N, Lièvre A, Orgerie MB, Jullian O, Sancho-Garnier H, et al. Low participation in organized colorectal cancer screening in France: underlying ethical issues. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2019;28(1):27-32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Lechopier N, Hamant C. Accompagner et prévenir. Tensions éthiques dans le dépistage du cancer colorectal. Sciences Sociales et Santé. 2017;35(4):5–28. [Google Scholar]; 72. Lechopier N, Hamant C. Accompagner et prévenir. Tensions éthiques dans le dépistage du cancer colorectal. Sciences Sociales et Santé. 2017;35(4):5-28.

- 73.Hogg R, Kennedy C, Gray C, Hanley J. Supporting the case for ‘progressive universalism’ in health visiting: Scottish mothers and health visitors’ perspectives on targeting and rationing health visiting services, with a focus on the Lothian Child Concern Model. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(1-2):240–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 73. Hogg R, Kennedy C, Gray C, Hanley J. Supporting the case for ‘progressive universalism’ in health visiting: Scottish mothers and health visitors’ perspectives on targeting and rationing health visiting services, with a focus on the Lothian Child Concern Model. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(1-2):240-50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Bekken W. Public Health Coordinator – How to Promote Focus on Social Inequality at a Local Level, and How Should It Be Included in Public Health Policies? Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(11):1061–1063. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 74. Bekken W. Public Health Coordinator – How to Promote Focus on Social Inequality at a Local Level, and How Should It Be Included in Public Health Policies? Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(11):1061-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]