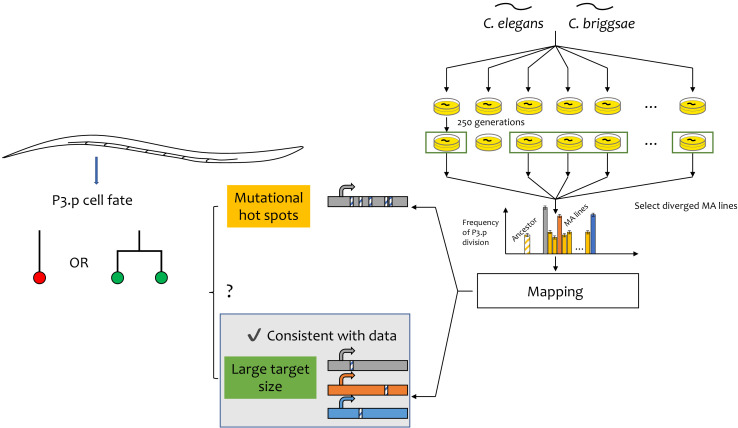

Figure 1. Fast evolution of a cell-fate decision in C. elegans and C. briggsae.

The vulva in Caenorhabditis worms develops from six precursor cells. In some individuals, the most anterior of these cells (called P3.p) divides during development; in other worms it does not (left). The chance of it dividing differs between species. Cell division in the other five vulval precursor cells (VPCs; left) does not vary. This faster evolution of P3.p may be due due to mutational hotspots (if the genes that regulate this decision have a relatively high mutation rate) or to a large target size (if there are relatively more genes that affect this decision). Besnard et al. used a mutation accumulation (MA) approach in two species – C. elegans and C. briggsae – to distinguish between the two explanations (right). They examined the MA lines in which the decision frequency differed the most from the ancestor (shown by the vertical grey, orange and blue bars in the graph) and identified the genes responsible (shown by the horizontal grey, orange and blue bars at the bottom of the figure). They found that none of these genes appear to be in a mutational hotspot and that they have a range of different biological roles. In this case, fast evolution is due to a large mutational target size.