Abstract

The interaction between the main carrier (serum albumin, SA) of endogenous and exogenous compounds in the bloodstream of different species (human, bovine, canine, rat, rabbit, and sheep) and a general anesthetic agent (propofol, PR) was investigated using an experimental technique (high-performance liquid chromatography) and computational methods (molecular docking, molecular dynamics, sequence, and phylogenetic analyses). The obtained results revealed the differences in the PR binding affinity to various homologous forms of this protein with reliable statistics (R2 = 0.9 and p-value < 0.005), correlating with the evolutionary relationships among SAs from different species. Additionally, the protein conformational changes (root-mean-square deviation ≈ 1.0 Å) and amino acid conservation of binding sites in protein domains were detected, contributing to the SA–PR binding modes. Overall, the outcomes from this study might provide a novel methodology to assess protein–ligand interactions and to gain some interesting insights into drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics to explain its variations among different species.

Introduction

Propofol (PR) is an intravenous short-acting agent widely used in clinical practice for the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia and also for the seduction of patients.1 This drug is well-known to bind to plasma proteins, mainly serum albumin (SA), with high affinity because of its lipophilic nature.2,3 In most of the cases, approximately 80% of PR will be bound to SA after intravenous injection, which will lead to significant changes in the pharmacologically active concentration of the anesthetic.4

It is important to investigate the mechanism of SA–PR interactions because only a minor fraction of the circulating drug can reach its site of action crossing biological barriers, such as the blood–brain barrier.3 Additionally, different ligand-binding sites (PR1 and PR2 for PR) in the SA homologous domains had been discovered previously, which might have some variations in different species caused by mutations in the protein-coding gene.5,6 In particular, the binding of warfarin and diazepam can be altered by single amino acid substitutions located apart from each other or by relatively few mutations, affecting the Lys313–Asp365 region of SA.7,8 However, in almost all known genetic variants of human SA, the point mutations leading to charge modifications are positioned on the surface of the protein structure; therefore, it is highly unlikely that the mutated residues might interfere with buried binding sites.8

Recently, some researchers had found that some variations in the V-shaped cavity of SAs from mammals, apes, reptiles, amphibians, and fish could be associated with the FA1 binding site for heme, bilirubin, fatty acids, and various exogenous compounds.9,10 In contrast, PR has been shown to bind to Sudlow’s site II, which is located at some distance from the FA1 site (IB) and in the different subdomain (IIIA) of SA.5,8 On the other hand, the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) analysis of PR was conducted mainly in animals, including mice, rats, dogs, and so forth, which might impose big difficulties when comparing these data with those of clinical trials.11,12 Therefore, the PR-binding properties to SAs from different species are needed to be assessed and precisely quantified. With that in mind, we investigated the PR-binding properties to SAs from different species, including the human (HSA), bovine (BSA), canine (CSA), rat (RatSA), rabbit (RSA), and sheep (SSA) SAs, to assess species-dependent differences of this binding process and its underlying molecular mechanisms.

Results and Discussion

Prior to any in silico simulation and modeling experiments, we analyzed the PR affinity to SA from different species described by measuring the unbound concentration of the drug associated with the 50% drop in SA concentration as UC50, using one-phase decay curve fitting data. This novel parameter can be used as the experimental alternative to effective (EC50) or inhibitory (IC50) concentration indexes, evaluating a 50% response reduction, which are widely applied in modern PD research.13,14

After drug incubation with the protein, fuprop was extracted by adding hydrochloric acid to the solution, causing the SA–PR complexes to settle down as a solid residue with HClO4 to be subsequently quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Figure 1A,B). In our cell-free experiments, we used the reference albumin concentration, approximately 35 mg/mL, to mimic the albumin-binding properties of plasma.15 PR (10 μg/mL) as a total fraction was adjusted according to the previously published quality control data for plasma samples with a similar concentration of this anesthetic.16 According to the SA–PR affinity parameters (Figure 1A–C), the drug was found to bind to all SAs to a high extent (% SAB ≈ 80%) because of its high lipid solubility (log P = 4.16). Moreover, PR as an acidic compound was also predicted to predominantly bind to the reference protein (log KaHSA = 4.03) with a very high plasma protein binding (% PPB = 96–98%) rate.17 Therefore, the real fuprop in the blood would be less than 4%, judging by the measurements of the PR unbound fraction in arterial plasma via equilibrium dialysis.18 The lowest UC50 values were detected for CSA–PR and HSA–PR complexes, indicating the strongest affinity between the protein and its ligand (Table 1), which were further confirmed by the in silico experiments.

Figure 1.

PR unbound fraction [fuprop, (A,B)] determined by HPLC and calculated bound fraction [fbprop, (C,D)] after its binding to SAs from different species.

Table 1. SA–PR Binding Values Calculated from the fu Curves for the Analyzed Complexes of SAs with PR by Using HPLCa.

| complex | UC50, μg/mL | CSA, mg/mL | D, μg/mL | fu0, μg/mL | % SAB, % | plateau, μg/mL | K (mg/mL)−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSA–PR | 3.27 | 9.21 | 7.43 | 9.61 | 77.32 | 2.18 | 0.11 |

| CSA–PR | 2.57 | 6.75 | 8.12 | 10.09 | 80.48 | 1.97 | 0.15 |

| HSA–PR | 2.64 | 7.82 | 7.43 | 9.29 | 79.97 | 1.86 | 0.13 |

| RatSA–PR | 2.99 | 8.38 | 8.18 | 9.97 | 81.94 | 1.79 | 0.11 |

| RSA–PR | 2.93 | 8.56 | 7.72 | 9.7 | 79.58 | 1.98 | 0.12 |

| SSA–PR | 3.64 | 8.47 | 8.27 | 10.18 | 81.23 | 1.91 | 0.09 |

CS is the protein concentration constant.

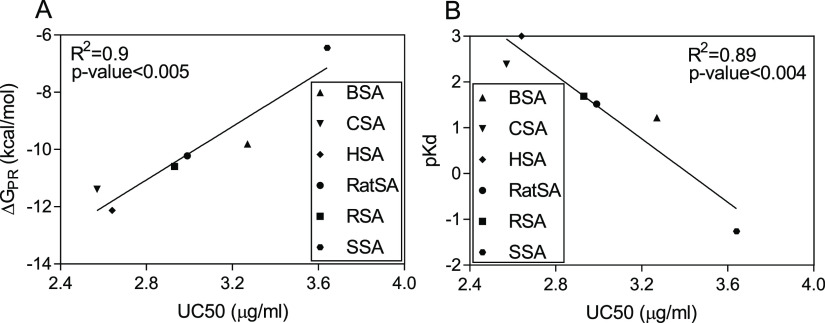

To gain a better insight into the PR interaction with SAs from different species, molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were carried out. The molecular docking analysis of protein–ligand binding poses (Figure 2A–F) performed with the AutoDock genetic algorithm showed that the PR interactions with SAs were thermodynamically favorable (Table 2). In particular, the ΔG differences were detected for the distinct PR-binding sites: PR1 and PR2. The former represented higher binding properties of the ligand to SAs, which was already confirmed in our previous study with a ΔGPBSA value of −23.44 kcal/mol for PR1 and only −19.03 kcal/mol for PR2.19 Furthermore, a strong correlation was observed for the predicted values (ΔGPR and pKd) and experimental results (UC50) with R2 = 0.9, p-value < 0.005 for the free energy of binding and R2 = 0.89, p-value < 0.004 for the dissociation constant (Figure 3A,B). Besides, the MD simulations were carried out further to investigate the dynamics of protein–ligand binding for the CSA–PR and HSA–PR complexes, applying implicit solvation models for the approximation of thermodynamics properties of liquids.20 As a result, the PR binding affinities calculated using implicit solvation modeling [generalized Born surface area (GBSA) and Poisson−Boltzmann surface area (PBSA)] corroborated well with the chromatographic and molecular docking data, confirming the following pattern: ΔGGBSAPR1 < ΔGGBSA, ΔGPBSAPR1 < ΔGPBSA, ΔGGBSA/PBSAPR1 for CSA–PR < ΔGGBSA/PBSA for HSA–PR, ΔGGBSA/PBSAPR2 for CSA–PR > ΔGGBSA/PBSA for HSA–PR, ΔGGBSAPR for CSA–PR < ΔGGBSA for HSA–PR, and ΔGPBSAPR for CSA–PR > ΔGPBSA for HSA–PR (Table 3). The discrepancies in the PR binding affinities to CSA and HSA might be linked to the difference (0.07) between UC50 values of PR unbound to these proteins, which is even smaller than the fu0 standard error found in the range from 0.09 to 0.16 μg/mL.

Figure 2.

Predicted molecular docking poses of PR bound to different SAs, including BSA (A), CSA (B), HSA (C), RatSA (D), RSA (E), and SSA (F), at PR1- and PR2-binding sites. All proteins are visualized as cartoon models and colored in gray. X-ray model of PR (sticks) and its binding poses (lines) are colored in green and magenta, respectively.

Table 2. Calculated Binding Affinity Values for the Analyzed Complexes of SAs with PRa.

| complex | ΔGPR1, kcal/mol | ΔGPR2, kcal/mol | ΔGPR, kcal/mol | Kd, μM | pKd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSA–PR | –5.99 | –3.82 | –9.81 | 0.06 | 1.22 |

| CSA–PR | –6.52 | –4.87 | –11.39 | 0.004 | 2.39 |

| HSA–PR | –6.14 | –5.99 | –12.13 | 0.001 | 3 |

| RatSA–PR | –6.05 | –4.17 | –10.22 | 0.03 | 1.52 |

| RSA–PR | –5.79 | –4.81 | –10.6 | 0.02 | 1.69 |

| SSA–PR | –6.45 | 0.0 | –6.45 | 17.99 | –1.26 |

ΔGPR = ΔGPR1 + ΔGPR2.

Figure 3.

Relationship between experimental (UC50) and predicted values: ΔGPR (A) and pKd (B) using linear regression analysis to measure the PR binding strength to SAs from different species.

Table 3. Calculated Binding Affinities (kcal/mol) for the Analyzed Complexes of SAs with PRa,b.

| complex | ΔGGBSAPR1 | ΔGPBSAPR1 | ΔGGBSAPR2 | ΔGPBSAPR2 | ΔGGBSAPR | ΔGPBSAPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSA–PR | –32.1 | –12.55 | –24.16 | –0.43 | –56.26 | –12.98 |

| HSA–PR | –28.95 | –8.69 | –24.38 | –5.42 | –53.34 | –14.11 |

ΔGGBSAPR = ΔGGBSA + ΔGGBSAPR2.

ΔGPBSAPR = ΔGPBSA + ΔGPBSAPR2.

The phylogenetic analysis of protein sequence data revealed three paired groups of closely related SAs (BSA–SSA, CSA–HSA, and RatSA–RSA) belonging to certain species of mammalian genera. The SA phylogenetic tree was able to cluster the mammalian species with high bootstrap values (Figure 4A). This tree, in conjunction with experimental and theoretical data from the HPLC and molecular docking/MD analyses, supports the hypothesis that the binding affinity of PR to SAs is dependent on the evolutionary distances of the protein-coding sequences. Indeed, the CSA–HSA group was associated with the highest levels of PR binding to the corresponding proteins. Moreover, it was observed from the sequence and structural alignments that the overall sequence identities (>70%) and similarities (>80%) of SAs from different species were very high across the albumin family (Table 4). This high degree of protein sequence conservation contributed to the conformational stability of SAs, which is also characterized by the low root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) (≈1.0 Å) value (Figure 4B). In particular, the protein structures, comprising the HSA–CSA group, were discovered to be highly homologous with the biggest identity—similarity parameters (80.46 and 89.49%, respectively) and the minimal conformational change (RMSD = 0.83 Å). These findings could be linked to the study of Kruger and Overington, demonstrating that drug-like molecule binding is conserved for protein targets with sequence identity for more than 80%, which might be utilized as a predictive criterion for estimating polypharmacology.21,22

Figure 4.

Unrooted NJ tree (A) depicting the phylogenetic relationship and structural alignment (B) of SAs from different species. The protein amino acid sequences were aligned and the evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method. The percentages of replicate trees in which the associated sequences clustered together in the bootstrap test are shown next to the branches. The SA structures are colored in red (HSA), green (BSA), blue (CSA), yellow (RatSA), magenta (RSA), cyan (SSA), respectively. The HSA structure was used as a reference model.

Table 4. Sequence Identity (Ident) and Similarity (Sim) and Structural RMSD Differences of SA from Different Speciesa.

| structure/sequence | Ident, % | Sim, % | RMSD, Å |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSA | 75.6 | 87.62 | 1.16 |

| CSA | 80.46 | 89.49 | 0.83 |

| HSA | 100 | 100 | |

| RatSA | 73.52 | 86.95 | 0.99 |

| RSA | 74.22 | 87.68 | 0.98 |

| SSA | 74.91 | 87.29 | 1.2 |

HSA sequence and structure were used as a reference.

To investigate key amino acid residues playing an important role in the formation of PR1- and PR2-binding sites, conservation analysis was performed to estimate the evolutionary conservation of amino acid positions in protein molecules based on the phylogenetic relations between homologous sequences (Figure 5A,B). Most of the amino acids forming both binding sites were determined to be highly conserved, except for Ile388 and Ala449 for PR1 and Ser579 for PR2 of HSA. The previous phylogenetic analysis of the SA family, focusing on the inspection of ligand-binding sites, also revealed a high amino acid conservation pattern, and the mechanisms of allosteric modulation that could be restricted to higher vertebrates.23 These variable amino acids in PR1 had been shown as hydrophobic contacts to be involved in the interaction of HSA with disulfonic stilbene derivatives.24 However, Ala449 is exclusively present in the CSA and HSA structures, which might be explained by their high affinity to PR (Figure 6). This amino acid residue was also observed to mediate various protein–ligand interactions at the subdomain IIIA of the HSA structure.25,26 On the other hand, it was also reported that the variable amino acid in PR2 played a role in the formation of the hydrophobic pocket for dibutylimidazolium and 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium cationic compounds, suggesting the dominance of the hydrophobic force in the HSA interaction with imidazolium ionic liquids.27

Figure 5.

Amino acid conservation analysis of the PR1- (A) and PR2-binding (B) sites for SAs from different species. Amino acid residues are depicted as ball-and-stick models. The molecular surface is shown to virtualize the interior of binding sites. Hydrogen bonds are displayed as dashed lines. All labels for H-bond forming and highly variable amino acids are marked in red and bold, respectively. Hydrogen atoms are removed to enhance clarity. The HSA structure was used as a reference model.

Figure 6.

Sequence alignment of SAs from different species using the Molsoft ICM-Pro software. Amino acid residues are colored according to their conservation: green color indicates fully conserved residues; yellow marks conservative substitutions, and white, nonconserved residues. The protein secondary structure (α-helices and β-sheets) for HSA is shown for comparison. The 388, 449, and 579 positions are marked with a black box.

To explore the impact of the Ala579 residue located in PR2 of CSA on HSA–PR binding, the HSA mutant (S579A) was generated in silico using site-directed mutagenesis, also known as alanine-scanning mutagenesis.28 The alanine-scanning technique involves removing all unnecessary side-chain atoms except for the β-carbons to maintain the protein’s structural integrity. The protein–ligand-binding free energy differences upon alanine mutation of the variable residue (ΔΔGbind = ΔGbindwt – ΔGbind) were calculated for the molecular mechanics (MM)-PBSA/GBSA implicit solvation models of the HSA–PR complex. As hypothesized, the S579A mutation in the PR2-binding site of HSA was found to enhance the PR affinity to the protein with ΔΔGbind value of 0.67 kcal/mol only for MM-PBSA because of the increased similarity of the HSA- and CSA-binding pockets. Indeed, some authors had previously demonstrated that specific serine-to-alanine substitutions at protein domains could increase the biological activity of some proteins.29 The study of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) has also revealed a similar effect, where cysteine-to-alanine mutation of enzyme-active sites increases the affinity of the SAGA (Spt-Ada-Gcn5 acetyltransferase) DUB module for ubiquitin to sequester cellular pools of monoubiquitin and ubiquitin chains.100

Conversely, the MM-GBSA method indicated a small change in ΔΔGbind (−0.34 kcal/mol), showing a slight decrease in binding affinity caused by the S579A mutation. Although the MM-PBSA approach is considered to be more rigorous and superior to MM-GBSA in predicting binding free energies, these results should be further confirmed in additional experiments in vitro or in vivo.30−32

The entropy–enthalpy compensation analysis of SA–PR complexes revealed the exothermic mechanism (ΔH < 0) of the binding process (Table 5), leading to a more favorable binding enthalpy (ΔHGBSA = −96.83 kcal/mol and ΔHPBSA = −53.55 kcal/mol) for CSA–PR than for HSA–PR (ΔHGBSA = −89.66 kcal/mol and ΔHPBSA = −50.44 kcal/mol). A negative TΔS value for a biological complex expresses the decrease in available microstates as the protein and ligand bind to form the complex. This decrease in available microstates mainly results from the ligand being trapped and having restricted mobility while being bound to the receptor protein.33

Table 5. Entropy–Enthalpy Compensation Analysis (T = 298.15 K) of SA–PR Complexes Calculated from 50 ns MD Simulationsa,b.

| PR1 |

PR2 |

PR |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| term (kcal/mol) | CSA | HSA | CSA | HSA | CSA | HSA |

| TΔS | –21.34 | –17.66 | –19.23 | –18.67 | –40.57 | –36.33 |

| ΔHGBSA | –53.44 | –46.61 | –43.39 | –43.05 | –96.83 | –89.66 |

| ΔHPBSA | –33.89 | –26.35 | –19.66 | –24.09 | –53.55 | –50.44 |

ΔHGBSA = ΔGGBSA + TΔS.

ΔHPBSA = ΔGPBSA + TΔS.

Finally, the free energy decomposition analysis was employed to evaluate the energetic contribution of PR to CSA and HSA binding. As an outcome, the PR decomposition energy (ΔGdecomp) calculated either with the GBSA (ΔGdecompGBSA) or PBSA (ΔGdecomp) methodology was smaller for the HSA–PR complex (ΔGdecompGBSA = −14.29 kcal/mol and ΔGdecomp = −8.59 kcal/mol) than for the CSA–PR complex (ΔGdecompGBSA = −14.11 kcal/mol and ΔGdecomp = −6.18 kcal/mol), contributing significantly to the protein–ligand interaction in the former protein. Several studies have also documented the implementation of this type of analysis of similar protein–ligand systems to illustrate residue energetic contributions to interpret the binding modes of chemicals with SAs.34,35

Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the interaction between SAs from different species, including HSA, BSA, CSA, RatSA, RSA, and SSA, and the general anesthetic PR using HPLC and computational methods. The obtained experimental results exhibited the differences in the PR binding affinity to various homologous forms of SA and correlated with the theoretical data with R2 = 0.9, p-value < 0.005 for ΔGPR, and R2 = 0.89, p-value < 0.004 for pKd. The strongest PR binding was detected for CSA and HSA, which can be explained by the close evolutionary relationship between these protein structures. Furthermore, the sequence and 3D structural analyses of these SAs reported the highest degree of identity and similarity of their amino acid sequences, minimal deviation rate between their 3D conformations, and the presence of Ala449 in the PR1-binding site. The alanine scanning analysis should be further confirmed in the protein–ligand binding experiments, using in vitro site-directed mutagenesis or similar techniques to produce the specific single-point mutation in PR1 and PR2. Finally, the results of this study might provide useful information for drug PK/PD to anticipate its mechanism of action in different species.

Experimental Section

PR Measurements

2,6-Diisopropylphenol or PR (purity ≥ 99%, ID: P185), perchloric acid (HClO4, purity ≥ 60%, ID: 311413), HSA (purity ≥ 98%, ID: SRP6182), BSA (purity ≥ 98%, ID: 05470), CSA (purity ≥ 95%, ID: RAB1198), RatSA (purity ≥ 99%, ID: A6414), RSA (purity ≥ 99%, ID: A0764), and SSA (purity ≥ 95%, ID: A3264) from different species were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Methanol (70%), ammonium hydroxide (25%), and ammonium bicarbonate were purchased from Promochem (Wesel, Germany) and Fluka Analytical (Steinheim, Germany). The SA structures were dissolved in distilled water in the concentrations starting from 0.5 up to 34.78 mg/mL. After the addition of PR (10 μg) to each concentration of SA, the mixture was incubated for 3 min at room temperature, and the protein fraction was precipitated by adding 0.025 mL of 70% HClO4 and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm at 22 °C for 5 min. The incubation time used was 3 min to mimic the PR duration of action after bolus dose according to the drug PK/PD data.36 After that, 170 μL of the supernatant was measured by HPLC–tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS/MS) to determine the PR unbound fraction (fuprop) according to a detailed protocol. Additionally, the bound PR fraction (fbprop) was assessed as a difference of the fu0 and fuprop values according to the equation

| 1 |

where fu0 is the unbound fraction (fu) of PR when the SA concentration is zero.

Glass vials were used in our experiments to prevent drug loss via its interaction with plastic walls.

The UC50 value as the unbound concentration of PR associated with the 50% drop in SA concentration (17.39 mg/mL) was calculated from the following equation based on one-phase decay function for the curve fitting

| 2 |

where K is the rate constant, and plateau is the fuprop value at infinite protein concentration, expressed in the same units. The % SAB value as the approximate estimate of SA binding was calculated from the following equation

| 3 |

where D is the difference between fu0 and plateau.

All the experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times. Statistical analyses were performed using linear and nonlinear regression modeling by the GraphPad Prism v.7 software for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The differences were considered statistically significant at a p-value of <0.05.

Molecular Descriptor Analysis

Molecular descriptors, including the octanol–water partition coefficient (log P) for PR together with the affinity constant (log KaHSA), were predicted for the reference complex (HSA–PR) by using the MarvinSketch and ACD/Labs algorithms.37,38

Molecular Docking

The SA structures were obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB IDs: 1e7a, 3v03, 3v09, 4luh, 5ghk) except for RatSA, which was produced by homology modeling using the SWISS-MODEL server and implementing the RSA structure (3v09) as a template.39 The PR structure was downloaded from the PubChem database as a 3D conformer (CID: 4943). Prior to molecular docking experiments, the stereochemical validation was achieved with the PROCHECK program for the protein models to assess the ϕ−ψ dihedral angles in a Ramachandran plot.40 The AutoDock algorithm was implemented to perform the molecular docking of PR to the binding sites of SA structures. The docking grids with a 3D size of 30 Å were used in the study.41 The location of SA-binding sites (PR1 and PR2) was acquired from our previously published experiments19 with Cartesian coordinates of 10.24 Å (x-axis), 2.11 Å (y-axis), and −13.75 Å (z-axis). The PyMOL molecular imaging software and in-house Python data processing scripts (https://github.com/virtualscreenlab/Virtual-Screen-Lab) were utilized to calculate the dissociation constants (Kd and pKd) from the ΔGbind (Gibbs free energy of binding) values, generate high-quality graphics, and analyze the results (PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.7.2.1, Schrödinger, LLC).

MD Simulations

All-atom MD simulations were performed using the AMBER 16 package with the FF99SB and general Amber force fields for the SA and PR molecules.42 The SA–PR systems were solvated with the TIP3P water models and neutralized with Na+ and Cl– ions using the tLEaP input script available from the AmberTools. Long-range electrostatic interactions were applied via the particle-mesh Ewald method.43 The SHAKE algorithm was used to constrain the length of covalent bonds, including hydrogen atoms.44 The Langevin thermostat was implemented to equilibrate the temperature of the systems at 300 K. A 2.0 fs time step was used for all simulations. The minimization and equilibration protocols were run for 10,000 steps and 10 ns. Finally, 50 ns classical MD simulations with no constraints were performed for each of SA–PR complexes using the MM-PBSA or MM-GBSA and surface area continuum solvation approaches.19 According to the standard protocol, we used the explicit solvation model for all MD simulations and later the implicit solvation (MM-PBSA/GBSA) as a postprocessing end-state method to calculate binding free energies of molecules in solution utilizing the Python script (MM-PBSA.py).

Evolutionary and Sequence Analyses

The evolutionary analysis was conducted by using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method45 with MEGA X software.46 The optimal tree with the sum of branch length of 0.76 was drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method47 and are in the units of the number of amino acid substitutions per site. The associated sequences were clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) to calculate the percentages of replicate trees.48 All ambiguous positions were removed for each sequence pair. The tree was scaled with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site with 609 positions in the final dataset. The evolutionary conservation analysis of PR1- and PR2-binding sites was performed by using the multisequence alignment with CLUSTALW and the ConSurf server for the identification of functional regions in proteins.49,50 Additional sequence analysis, including multiple sequence and pairwise alignments, was conducted with the ICM-Pro software (Molsoft LLC, San Diego, CA, USA).

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supporting Information files).

Acknowledgments

The authors of this work were supported by the following grants: MOST 106-2314-B-039-027-MY3, 108-2320-B-039-048, 108-2813-C-039-133-B, and 108-2314-B-039-016 from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. The authors (T.D.) are also grateful to the DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) organization for providing the project funding (374031971 – TRR 240/INF).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c01295.

HPLC protocol used in this study, information on the chemicals and protein concentrations used in the HPLC experiments, the main components of the HPLC–MS system, MS settings for the multiple reaction monitoring method, gradient HPLC parameters, the preparation of the calibration standards, and the calibration curve using 10 μg/mL of PR (PDF)

Raw data of the experimental and theoretical measurements, including the HPLC data, molecular docking results, phylogenetic and molecular homology data together with sequence and structural alignment outputs (ZIP)

Author Contributions

S.S. led and guided the study, performed all in silico simulations, made figures, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. A.F. performed the HPLC experiments. K.-P.S. and A.A.H. analyzed the corresponding data and participated in manuscript editing. T.D. and J.B. led and guided the study, analyzed sequences and structures and participated in the manuscript draft. All authors finalized the manuscript together.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Mazoit J. X.; Samii K. Binding of propofol to blood components: implications for pharmacokinetics and for pharmacodynamics. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1999, 47, 35–42. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schywalsky M.; Ihmsen H.; Knoll R.; Schwilden H. Binding of propofol to human serum albumin. Arzneimittelforschung 2011, 55, 303–306. 10.1055/s-0031-1296863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shityakov S.; Salmas R. E.; Durdagi S.; Salvador E.; Pápai K.; Yáñez-Gascón M. J.; Pérez-Sánchez H.; Puskás I.; Roewer N.; Förster C.; Broscheit J.-A. Characterization, in Vivo Evaluation, and Molecular Modeling of Different Propofol-Cyclodextrin Complexes To Assess Their Drug Delivery Potential at the Blood-Brain Barrier Level. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016, 56, 1914–1922. 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmayer P.; Büch U.; Büch H. P. Propofol Binding to Human Blood Proteins. Arzneimittelforschung 1995, 45, 1053–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A. A.; Curry S.; Franks N. P. Binding of the General Anesthetics Propofol and Halothane to Human Serum Albumin. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 38731–38738. 10.1074/jbc.m005460200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R.; Eckenhoff R. G. Weak polar interactions confer albumin binding site selectivity for haloether anesthetics. Anesthesiology 2005, 102, 799–805. 10.1097/00000542-200504000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragh-Hansen U.; Brennan S. O.; Galliano M.; Sugita O. Binding of warfarin, salicylate, and diazepam to genetic variants of human serum albumin with known mutations. Mol. Pharmacol. 1990, 37, 238–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasano M.; Curry S.; Terreno E.; Galliano M.; Fanali G.; Narciso P.; Notari S.; Ascenzi P. The extraordinary ligand binding properties of human serum albumin. IUBMB Life 2005, 57, 787–796. 10.1080/15216540500404093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascenzi P.; di Masi A.; Fanali G.; Fasano M. Heme-based catalytic properties of human serum albumin. Cell Death Discovery 2015, 1, 15025. 10.1038/cddiscovery.2015.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurdiansyah R.; Rifa’i M.; Widodo A Comparative Analysis of Serum Albumin from Different Species to Determine a Natural Source of Albumin That Might Be Useful for Human Therapy. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2016, 11, 243–249. 10.1016/j.jtumed.2016.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.-H.; Ghim J.-L.; Song M.-H.; Choi H.-G.; Choi B.-M.; Lee H.-M.; Lee E.-K.; Roh Y.-J.; Noh G.-J. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a new reformulated microemulsion and the long-chain triglyceride emulsion of propofol in beagle dogs. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 158, 1982–1995. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortal B. P.; Reitz S. L.; Aggarwal A.; Meng Q. C.; McKinstry-Wu A. R.; Kelz M. B.; Proekt A. Development and validation of brain target controlled infusion of propofol in mice. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0194949 10.1371/journal.pone.0194949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shityakov S.; Broscheit J.; Puskás I.; Roewer N.; Foerster C. Three-dimensional quantitative structure–activity relationship and docking studies in a series of anthocyanin derivatives as cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors. Adv. Appl. Bioinf. Chem. 2014, 7, 11–21. 10.2147/aabc.s56478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalvass J. C.; Olson E. R.; Cassidy M. P.; Selley D. E.; Pollack G. M. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of seven opioids in P-glycoprotein-competent mice: assessment of unbound brain EC50,u and correlation of in vitro, preclinical, and clinical data. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007, 323, 346–355. 10.1124/jpet.107.119560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.; Choi E. Y.; Kim D. J.; Kim J. H.; Kim T. S.; Oh S. W. A rapid, simple measurement of human albumin in whole blood using a fluorescence immunoassay (I). Clin. Chim. Acta 2004, 339, 147–156. 10.1016/j.cccn.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. S.; Zetterlund E.-L.; Gréen H.; Oscarsson A.; Zackrisson A.-L.; Svanborg E.; Lindholm M.-L.; Persson H.; Eintrei C. Pharmacogenetics, Plasma Concentrations, Clinical Signs and EEG During Propofol Treatment. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 115, 565–570. 10.1111/bcpt.12277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockshott I. D.; Douglas E. J.; Plummer G. F.; Simons P. J. The pharmacokinetics of propofol in laboratory animals. Xenobiotica 1992, 22, 369–375. 10.3109/00498259209046648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka H.; Yamamoto K.; Okano N.; Morita T.; Goto F.; Horiuchi R. Changes in drug plasma concentrations of an extensively bound and highly extracted drug, propofol, in response to altered plasma binding. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 75, 324–330. 10.1016/j.clpt.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shityakov S.; Roewer N.; Förster C.; Broscheit J.-A. In silico investigation of propofol binding sites in human serum albumin using explicit and implicit solvation models. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2017, 70, 191–197. 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Zhang H.; Wu T.; Wang Q.; van der Spoel D. Comparison of Implicit and Explicit Solvent Models for the Calculation of Solvation Free Energy in Organic Solvents. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 1034–1043. 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger F. A.; Overington J. P. Global analysis of small molecule binding to related protein targets. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, e1002333 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-C.; Tolbert R.; Aronov A. M.; McGaughey G.; Walters W. P.; Meireles L. Prediction of Protein Pairs Sharing Common Active Ligands Using Protein Sequence, Structure, and Ligand Similarity. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016, 56, 1734–1745. 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanali G.; Ascenzi P.; Bernardi G.; Fasano M. Sequence analysis of serum albumins reveals the molecular evolution of ligand recognition properties. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2012, 29, 1195–1205. 10.1080/07391102.2011.672632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaunet-Lahary T.; Vercauteren D. P.; Fleury F.; Laurent A. D. Computational simulations determining disulfonic stilbene derivative bioavailability within human serum albumin. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 18020–18030. 10.1039/c8cp00704g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi N.; Ajmal M. R.; Rabbani G.; Ahmad E.; Khan R. H. A comprehensive insight into binding of hippuric acid to human serum albumin: a study to uncover its impaired elimination through hemodialysis. PLoS One 2013, 8, e71422 10.1371/journal.pone.0071422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai A.; Yamasaki K.; Enokida T.; Miyamoto S.; Otagiri M. Crystal structure analysis of human serum albumin complexed with sodium 4-phenylbutyrate. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2018, 13, 78–82. 10.1016/j.bbrep.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y.; Liu M.; Chen S.; Chen X.; Wang J. New Insight into Molecular Interactions of Imidazolium Ionic Liquids with Bovine Serum Albumin. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 12306–12314. 10.1021/jp2071925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesto D. S.; Cerqueira N. M. F. S. A.; Ramos M. J.; Fernandes P. A. Discovery of new druggable sites in the anti-cholesterol target HMG-CoA reductase by computational alanine scanning mutagenesis. J. Mol. Model. 2014, 20, 2178. 10.1007/s00894-014-2178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockhaus J.; Nagatani A.; Halfter U.; Kay S.; Furuya M.; Chua N. H. Serine-to-alanine substitutions at the amino-terminal region of phytochrome A result in an increase in biological activity. Genes Dev. 1992, 6, 2364–2372. 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow M. E.; Morgan M. T.; Clerici M.; Growkova K.; Yan M.; Komander D.; Sixma T. K.; Simicek M.; Wolberger C. Active site alanine mutations convert deubiquitinases into high-affinity ubiquitin-binding proteins. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19 (10), e45680. 10.15252/embr.201745680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T.; Wang J.; Li Y.; Wang W. Assessing the Performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods. 1. The Accuracy of Binding Free Energy Calculations Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011, 51, 69–82. 10.1021/ci100275a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarukhanyan E.; Shityakov S.; Dandekar T. In Silico Designed Axl Receptor Blocking Drug Candidates Against Zika Virus Infection. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 5281–5290. 10.1021/acsomega.8b00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarukhanyan E.; Shityakov S.; Dandekar T. Rational Drug Design of Axl Tyrosine Kinase Type I Inhibitors as Promising Candidates Against Cancer. Front. Chem. 2020, 7, 920. 10.3389/fchem.2019.00920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds C. H.; Holloway M. K. Thermodynamics of ligand binding and efficiency. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 433–437. 10.1021/ml200010k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu X.; Gao X.; Wang H.; Wang X.; Wang S. Insight into the dynamic interaction between different flavonoids and bovine serum albumin using molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations. J. Mol. Model. 2013, 19, 1039–1047. 10.1007/s00894-012-1649-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonis G.; Avramopoulos A.; Papavasileiou K. D.; Reis H.; Steinbrecher T.; Papadopoulos M. G. A Comprehensive Computational Study of the Interaction between Human Serum Albumin and Fullerenes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 14971–14985. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b05998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinis-Oliveira R. J. Metabolic Profiles of Propofol and Fospropofol: Clinical and Forensic Interpretative Aspects. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–16. 10.1155/2018/6852857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masunov A. ACD/I-Lab 4.5: an internet service review. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2001, 41, 1093–1095. 10.1021/ci010400l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirok G.; Máté N.; Varga J.; Szegezdi J.; Vargyas M.; Dóránt S.; Csizmadia F. Making “Real” Molecules in Virtual Space. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2006, 46, 563–568. 10.1021/ci050373p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwede T.; Kopp J.; Guex N.; Peitsch M. C. SWISS-MODEL: An automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3381–3385. 10.1093/nar/gkg520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A.; Rullmannn J. A. C.; MacArthur M. W.; Kaptein R.; Thornton J. M. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 1996, 8, 477–486. 10.1007/bf00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodsell D. S.; Morris G. M.; Olson A. J. Automated docking of flexible ligands: applications of AutoDock. J. Mol. Recognit. 1996, 9, 1–5. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case D. A.; Cheatham T. E. 3rd; Darden T.; Gohlke H.; Luo R.; Merz K. M. Jr.; Onufriev A.; Simmerling C.; Wang B.; Woods R. J. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1668–1688. 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essmann U.; Perera L.; Berkowitz M. L.; Darden T.; Lee H.; Pedersen L. G. A Smooth Particle Mesh Ewald Method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 8577–8593. 10.1063/1.470117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S.; Kollman P. A. Settle: An analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithm for rigid water models. J. Comput. Chem. 1992, 13, 952–962. 10.1002/jcc.540130805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N.; Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Stecher G.; Li M.; Knyaz C.; Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerkandl E.; Pauling L.. Evolutionary divergence and convergence in proteins. In Evolving Genes and Proteins; Bryson V., Vogel H. J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, 1965; pp. 97–166. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. 10.2307/2408678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K.-B. ClustalW-MPI: ClustalW analysis using distributed and parallel computing. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 1585–1586. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazy H.; Abadi S.; Martz E.; Chay O.; Mayrose I.; Pupko T.; Ben-Tal N. ConSurf 2016: an improved methodology to estimate and visualize evolutionary conservation in macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W344–W350. 10.1093/nar/gkw408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supporting Information files).