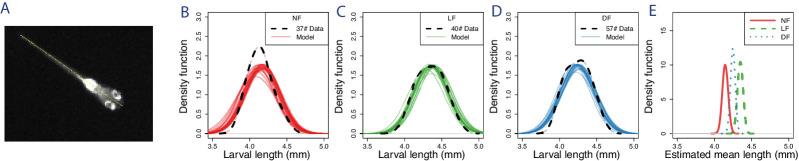

Appendix 1—figure 1. Analysis of larval length shows small statistical differences in mean length, with larvae on live-prey being the longest.

(A) Larval length is measured in pixels from mouth point to edge of tail on video frames when the larva is not in hunting mode and in straight posture. As the tail-fin is not visible or measured, our measurements are equivalent to the established developmental measures of standard-length (SL) (Parichy et al., 2009), which we convert from pixels to mm using an estimate of the mm/px calibration of our setup. (B–D) Distribution of body lengths in the different feeding regimes. Dotted black lines indicate kernel density smoothed distributions of measured larva lengths (Gaussian kernel BW = 0.1) and solid lines show 30 samples of likely body length distributions based on a Gaussian model fit, whose parameters (μ,σ) were estimated from the data using Bayesian inference. (E) The estimated probability densities of mean body length based on Gaussian model fitting. The estimated mean SL of each feeding group (NF = 4.15 mm, LF = 4.37 mm, DF = 4.21 mm) are distinct, (), () and (), with LF having the largest mean length, being larger to NF by and .