Abstract

Ethnopharmacological relevance

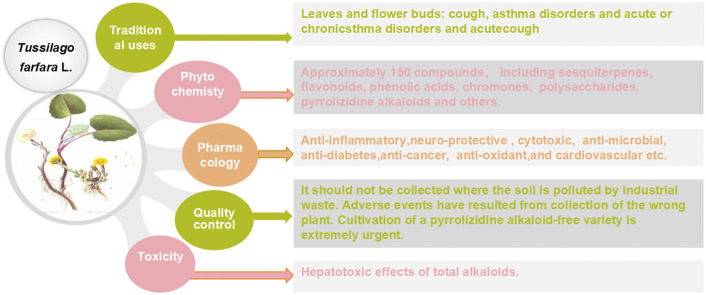

Tussilago farfara L. (commonly called coltsfoot), known as a vital folk medicine, have long been used to treat various respiratory disorders and consumed as a vegetable in many parts of the world since ancient times.

Aim of the review

This review aims to provide a critical evaluation of the current knowledge on the ethnobotanical value, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicity and quality control of coltsfoot, thus provide a basis for further investigations.

Materials and methods

A detailed literature search was obtained using various online search engines (e.g. Google Scholar, Web of Science, Science Direct, Baidu Scholar, PubMed and CNKI). Additional information was sourced from ethnobotanical literature focusing on Chinese and European flora. The plant synonyms were validated by the database ‘The Plant List’ (www.theplantlist.org).

Results

Coltsfoot has diverse uses in local and traditional medicine, but similarities have been noticed, specifically for relieving inflammatory conditions, respiratory and infectious diseases in humans. Regarding its pharmacological activities, many traditional uses of coltsfoot are supported by modern in vitro or in vivo pharmacological studies such as anti-inflammatory activities, neuro-protective activity, anti-diabetic, anti-oxidant activity. Quantitative analysis (e.g. GC-MS, UHPLC-MRMHR) indicated the presence of a rich (>150) pool of chemicals, including sesquiterpenes, phenolic acids, flavonoids, chromones, pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs) and others from its leaves and buds. In addition, adverse events have resulted from a collection of the wrong plant which contains PAs that became the subject of public concern attributed to their highly toxic.

Conclusions

So far, remarkable progress has been witnessed in phytochemistry and pharmacology of coltsfoot. Thus, some traditional uses have been well supported and clarified by modern pharmacological studies. Discovery of therapeutic natural products and novel structures in plants for future clinical and experimental studies are still a growing interest. Furthermore, well-designed studies in vitro particularly in vivo are required to establish links between the traditional uses and bioactivities, as well as ensure safety before clinical use. In addition, the good botanical identification of coltsfoot and content of morphologically close species is a precondition for quality supervision and control. Moreover, strict quality control measures are required in the studies investigating any aspect of the pharmacology and chemistry of coltsfoot.

Keywords: Tussilago farfara L., Ethnopharmacology, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, Toxicity, Quality control

Graphical abstract

List of abbreviations

- ACAE

acarbose equivalent

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- BV-2

mouse microglia cells

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2 expression

- CLP

cecal ligation and puncture

- DSS

dextran sulfate sodium

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- ECN

7β-(3-ethyl-cis-crotonoyloxy)-1α-(2-methylbutyryloxy)-3,14-dehydro-Z-notonipetranone

- EtOAc

ethyl acetate

- GC-FID

gas chromatography–flame ionization detector

- GC-MS

gas chromatography– mass spectrometry

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- HepG2

human liver hepatocellular carcinoma cells

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- HPIPC

ion-pair high-performance liquid chromatography

- HK-2

human kidney 2 cell

- HEp-2

Human larynx epidermoid carcinoma cell

- RD

human rhabdomyosarcoma

- IMQ

imiquimod

- iNOS

nitric oxide synthase

- IC50

50% inhibitory concentration

- JNK

Jun N-terminal kinase

- CLP

cecal ligation and puncture

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- LCDD

lung cleansing and detoxifying decoction

- LC-ESI-MS/MS

liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry

- LC50

50% lethal concentration

- LD50

50% lethal dose

- MAE

microwave-assisted extraction

- MeOH

methanol

- MMP

mitochondrial membrane potential

- mTOR

mechanistic target of rapamycin

- MS

mass spectrometer

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- PE

petroleum ether

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PDA

photodiode array

- PAs

pyrrolizidine alkaloids

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- RAW264.7

mouse leukemic monocyte macrophage

- PHWE

pressurised hot water extraction

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor

- TCMs

traditional Chinese medicines

- TSL

tussilagone

- TRAIL

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- TNG

Tussilagonone

- UPC2

ultra-high performance supercritical fluid chromatography

1. Introduction

Tussilago farfara L. (coltsfoot), a perennial plant, is the only species within the Tussilago genus (Composite). As an outstanding lung herb, in the USA the root of coltsfoot has medicinal values for debilitated coughs, whooping cough and humid forms of asthma (Tobyn et al., 2011). In Norway, the dried and cut leaves of coltsfoot, as folk medicines, are sold and used in teas for the relief of coughs and chest complaints (Xue et al., 2012). In Europe, the leaves are used to treat bronchial infections while in China the flower buds are preferred (Adamczak et al., 2013). Moreover, in traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs), the flower bud of coltsfoot is often used the form of processed honey-fry, which showed a detoxifying effect. It also has been used as a dietary supplement and health tea in many countries (Kang et al., 2016; Tobyn et al., 2011). Traditionally, leaves of the plant especially in European countries, are widely used by indigenous people against a wide range of ailments, including gastrointestinal, wounds, burns, urinary, injury's inflammation within the eye and mainly the relief of respiratory complaints (Jaric et al., 2018; Rigat et al., 2015). As an important folk medicine, coltsfoot has been studied for its pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory (Cheon et al., 2018),anti-oxidative (Kim et al., 2006; Qin, K. et al., 2014), anti-microbial (Uysal et al., 2018), anti-diabetic (Gao et al., 2008), neuro-protection, (Lee et al., 2018), platelet anti-aggregation (Hwang et al., 1987), and anti-cancer (Li et al., 2014) etc. As well as, several investigations have evaluated the phytochemistry of coltsfoot. Approximately 150 compounds have been identified, including sesquiterpenoids (Qin et al., 2014), triterpenoids (Yaoita et al., 2012) flavonoids (Kim et al., 2006), phenolic acids (Kuroda et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019), chromones (Sun et al., 2019), pyrrolizidine alkaloids (Nedelcheva et al., 2015) and others. Some of them have been deemed to possess biological activities, and this is notably the case with TSL (13). Most notably, the concentration of PAs in coltsfoot varies widely (Adamczak et al., 2013) and cultivation of a PAs-free variety is being developed in Austria, (Wawrosch et al., 2000). Moreover, Pfeiffer et al. (2008) highlights the correlation of vegetative multiplication in coltsfoot, as an important pioneer species, which has been achieved rapidly via repeated clonal growth and subsequent clonal reproduction (Pfeiffer et al., 2008).

As coltsfoot is widely consumed as a vegetable, it is imperative to evaluate its biological attributes to support it prospective uses as functional foods (Uysal et al., 2018).

This review addresses specifically on the ethnobotanical value, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicity and quality control coltsfoot, and to analyses critically the reported studies, with the purpose of providing the theoretical basis for the clinical application of Tussilago farfara L.

2. Materials and methods

All relevant information was obtained through searching scientific databases, (e.g. PubMed, Web of science, Google Scholar, Springer, and CNKI), using the keywords, Tussilago farfara L., Farfarae Flos and coltsfoot. Additional information was sourced from ethnobotanical literature focusing on European flora. We also sought further information on herb from flora of China and local herbal classic literature, such as Divine Farmers Materia Medica (Han Dynasty, A.D. 25–220), Compendium of Materia Medica (Ming Dynasty A.D. 1368–1644, written by Li Shizhen A.D. 1518–1593), She Sheng Zhong Miao Prescription (Ming Dynasty, Zhang Shiche, A.D. 1500–1577), Wei Sheng Bao Jian (written by Luo Tianyi, published in A.D. 1343), Pu Ji Prescription (Ming Dynasty, published in A.D 1390), Qian jing Prescription (Tang Dynasty, written by Sun Simiao, published in 652) and The handbook of prescriptions for emergencies (Jin Dynasty, A.D. 317–420, written by Tao Hongjing A.D.456─536) etc. Besides, some official websites provided some relevant information.

All chemical structures were described using Chem Draw Pro 7.0 software.

3. Botanical description, distribution and habitat

3.1. Taxonomy and morphology

In the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2015), one species of the genus Tussilago has been registered as ‘Kuan-Dong-Hua’, denoting Tussilago farfara L., which is a flowering perennial plant. Tussilago farfara L. is known as ‘podbel’ (bottom is white) in Bulgaria (Nedelcheva et al., 2015), ‘Kantoka’ in Japan (https://kampo.ca/herbs-formulas/herbs/kantoka/). According to “Plant of world online”, Tussilago farfara L. is the only accepted name for the plant, with other 10 synonyms. The synonyms with the highest confidence levels, include Cineraria farfara (L.) Bernh., Tussilago alpestris Hegetschw., Tussilago radiata Gilib. and Tussilago umbertina Borbás (http://plantsoftheworldonline.org/). However, the value of positive identification is of great importance prior to exploring functional phytochemicals and potential health benefits from botanicals.

In terms of morphology, the principal botanical characteristics of coltsfoot, including the whole plant, leaves, flower buds and flowers are highlighted here (Fig. 1 ). Above ground, the plants reach 5–15 cm height, although up to 30 cm during fruit dispersal (Norani et al., 2019). The flower buds are in the shape of a long round rod and single or 2 to 3 consecutive bases, with a length of 12.5 cm and a diameter of 0.5–1 cm (Chinese Pharmacopoeia, 2015). It also owns upper thick, lower tapering or with short pedicel, outer covered with many fish-scale bracts and fragrant smell. The flower buds of coltsfoot precede the leaves and appear early (February–April) in the year, bearing bright yellow and dandelion-like flowers (Norani et al., 2019; Zhi et al., 2012). The large, round, heart-shaped leaves with long petioles, 3–12 cm long and 4–14 cm wide and have radial veins and crinkly, slightly toothed edges palmately reticulated veins. They have a thick white downy covering underneath (Tobyn et al., 2011) (www.iplant.cn/frps). However, there are few reports on chemical components in roots of coltsfoot. Thus, chemical studies on the components from this need to be strengthened.

Fig. 1.

Images of Tussilago farfara L. (coltsfoot) (a) whole-plant of coltsfoot picture adapted from (Tobyn et al., 2011); (b) leaves of coltsfoot; (c) flowers of coltsfoot.

3.2. Distribution and habitat

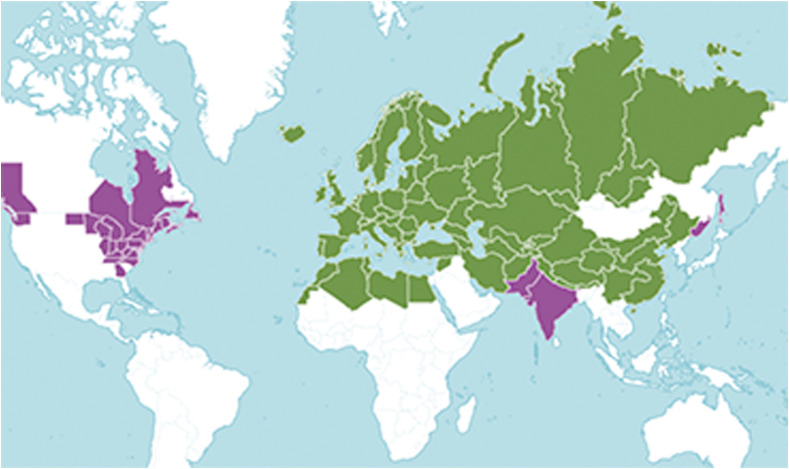

Although coltsfoot occurs naturally and indigenous to the temperate Eurasia to N. Africa and Nepal,it is currently distributed in up to 46 countries around the world (http://plantsoftheworldonline.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:30006161-2), ( Fig. 2 ). In China, the wild resources are present in at least 10 provinces, particularly in the Yellow River basin area of provinces (http://www.iplant.cn/). Coltsfoot has become naturalized in tropical and temperate areas where it grows wild as a weed in river banks, roadsides, wastelands and crop fields, cultivated or uncultivated (www.discoverlife.org). In introduced areas, coltsfoot can quickly form dense stands that aggressively invade well-established cultivated lands, with some regarding it as being naturalized as a causal weed in American. Hence, it may be of particular interest for the sustainable development of new drugs or other derived products, since adequate amounts of raw material are always available.

Fig. 2.

Distribution map of coltsfoot Native Introduction reproduced from (http://plantsoftheworldonline.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:30006161-2).

4. Local and conventional medicinal uses

Coltsfoot is listed as a “Middle grade” drug in the Divine Farmers Materia Medica (Han Dynasty, A.D. 25–220), the oldest book on Chinese medicine. It was also recorded in many ancient classic traditional Chinese medicine books such as the Compendium of Materia Medica (Ming Dynasty), written by Li Shi Zhen, extensively described the function of coltsfoot, which can be a remedy for chronic cough, phlegm syndromes with blood and chancre the mouth. The Collective Notes to Canon of Materia Medica (Nan Dynasty, written by Tao Hongjing, A.D. 456─536, published in A.D. 502–557) describes the flower of coltsfoot as possessing a pungent, wen, non-toxic nature. It can primarily treat cough inverse of breath, sore throat, epilepsy induced by terror, chills and fever and evil. As well as, it can be applied for treating diabetes and gasping respiration. According to the Amplification on Materia Medica (Song Dynasty, A.D. 960–1279, published in A.D. 1116) written by Kou Zongshi, spring into or when mining to vegetables, as medicine this herb is good to see the flower slightly. Moreover, coltsfoot and its ten Chinese patent medicines (Ju Hong Tablets/Pills/granula and capsule, Qingfei Huatan Pills, Runfei Zhisou Pills, Zhisou Huatan Pills, Ermu Ansou Pills, Jiegong Donghua Pills and Chuanbei Xueli Gao) were recorded in Chinese pharmacopoeia (Pharmacopoeia Committee of China, 2015). Coltsfoot has widespread cultural uses in many countries. Several ethnomedicinal survey studies were conducted and highlighted the customary uses of coltsfoot. The most common focus on its leaves and flower buds.

A list of commonly known prescriptions and products containing coltsfoot are presented in Table 1 . And patent in Table 2 .

Table 1.

Traditional and clinical applications of Tussilago farfara L. (coltsfoot).

| Herbal formulations | Ingredients | Country/Region | Traditional uses/modern used | Preparation and administration | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The lung cleansing and detoxifying decoction (LCDD) | Ephedra sinica, Cinnamomum cassia (twig), Alisma plantago-aquatica, Atractylodes macrocephala, Bupleurum chinense, Scutellaria baicalensis, Tussilago farfara etc. | China | Widely used in treating COVID-19 Patients | Decoction | Weng (2020) |

| Skin pigmentum | Farfarae folium | Spain | Bacterial skin disease (Anthrax, Boils) | Apply leaves on the skin | Rigat et al. (2015) |

| Hormone Rejuvenator | Bilberry bark, cascara sagrada, chamomile, chickweed etc. | Europe | Nd | Capsule | Hirono et al. (1976) |

| Bronchostad® | Made from coltsfoot leaves | Europe | which can also be used to prepare liquid and solid extracts | Instant tea | Hirono et al. (1976) |

| Recipe | Coltsfoot, marshmallow leaf Althaea officinalis, elecampane Inula helenium, capsicum Capsicum annuum | Europe | To heal ‘buchas’, cough, shortness of breath, asthma | Decoction | Tobyn et al. (2011) |

| Tobacco | Coltsfoot, buckbean menyanthes trifoliata, eyebright euphrasia officinalis, betony stachys officinalis, rosemary rosmarinus officinalis, thyme thumus vulgaris lav, ender lavandula angustifolia and chamomile flowers matricaria recutita | Europe | Relives asthma and old bronchitis, catarrh and other lung troubles | Tobacco | Tobyn et al. (2011) |

| Kuan Donghua Tang | Tussilago farfara, Morus alba L, Fritillaria cirrhosa, Schisandra chinensis, Glycyrrhiza uralensis, Anemarrhena asphodeloides, Amygdalus Communis | China | For erupting cough | Decoction | General Records of Holy Universal Relief (Song Dynasty) |

| Kuan Hua Tang | Tussilago farfara, Glycyrrhiza uralensis, Platycodon grandifloras, Semen Coicis | China | Treatment of lung carbuncle and chest full of cold, pulse count, dry throat, great thirst, turbid saliva, stinky pus like japonica rice gruel | Decoction | Chuang Shang Jing Yan book⟪疮疡经验全书⟫ |

| Ding Chuan Tang | Ginkgo biloba, Ephedra sinica, Perilla frutescens, Tussilago farfara etc. | China | Treating for bronchial asthma, asthma bronchitis etc. | Decoction | Sheng Zhong Miao Prescription (Ming Dynasty) |

| Kuan Dong Jian | Tussilago farfara, Zingiber officinale, Aster tataricus, Schisandra chinensis | China | Treatment of cough with cold | Decoction | Thousand Pieces of Gold Formulae (Tang Dynasty) |

| Zi Wan San | Tussilago farfara, Aster tataricus | China | Cure a persistent cough | pulvis | Sheng Hui Prescription⟪圣惠方⟫ |

| Jiu Xian San | Panax ginseng, Tussilago farfara, Morus alba, Platycodon grandifloras etc. | China | Chronic Cough of Qi and blood deficiency | pulvis | Wei Sheng Bao Jian⟪卫生宝鉴⟫ |

| Bai Hua Gao | Tussilago farfara, Lilium brownii var. | China | Treat asthma, cough and sputum with blood | Pill | Ji Sheng Prescription⟪济生方⟫ |

| External preparation | The flower buds of coltsfoot | China | Treatment of hemorrhoid and fistula | The flower buds of coltsfoot into fine powde and then rapply with Water | Hu Nan Yao Wu Zhi⟪湖南药物志⟫ |

| Alcohol extract | The flower buds of coltsfoot | China | Treat asthma | Oral 5 ml (equivalent to 6 g of crude drug, 3 times a day, observation for 1 week | Great Traditional Chinese Medicine Dictionary (Shanghai Science and Technology Publishers) |

| Compound coltsfoot injection |

Tussilago farfara, Senecio pendulus |

China | Treatment of chronic bronchitis and anti-hypertensive effect | Each intramuscular injection of 2 ml, continuous medication for 10 days | Great Traditional Chinese Medicine Dictionary (Shanghai Science and Technology Publishers) |

| External preparation | The flower buds of coltsfoot | China | Treatment of chronic osteomyelitis | Make a paste, apply it to a disinfecting cloth, wash the patients with sinus tract with light saline, according to the size of the injured surface | Great Traditional Chinese Medicine Dictionary (Shanghai Science and Technology Publishers) |

Notes.

“Qi”: In ancient China, it is believed that Qi constitutes one of the basic substances of the body and maintain human life activities. People in China deemed that everything in the universe resulted from the movement and changed of Qi.

“Cold”: pain that is worse for cold and improved by warmth.

Nd: no date.

Table 2.

Some Tussilago farfara L. (coltsfoot) related patents.

| Food products | Title of the patent | Information about the patent | Patent numbers and date approved | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicament | Composition, comprising tussilagone compound isolated from Tussilago farfara L. extract, for prevention and treatment of cancer and use thereof | The invention relates to the preparation of tussilagone from Tussilago farfara L. and treatment of cancer as a substituent for a conventional anticancer agent | KR20180056599 2018-05-17 | Korea |

| Medicament | The pharmaceutical Composition for prevention or treatment of cancer comprising an extract of Tussilago farfara L. and TRAIL | The invention relates to a new TRAIL sensitizer of Tussilago farfara L. extract, which can enhance an anti-cancer effect of the TRAIL by increasing apoptotic susceptibility of TRAIL | KR20130065367 2013-06-07 | Korea |

| Medicament | Use of extract from leaves of Tussilago farfara L. as antiulcer agent | The use of the extract from the leaves of Tussilago farfara L. as antiulcer agent | UAU201312799U 2013-11-04 | USA |

| Medicament | Composition and health function food for treating brain cancer comprising Tussilago farfara L. flower extract | The invention relates to a novel use of Tussilago farfara L. flower ethanol extract, which relates to a composition for preventing and treating brain cancer by inhibiting growth and inducing death of cancer cells | KR20110012204 2011-02-11 | Korea |

| Medicament | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory herbal remedy, useful e.g. for external application to treat injuries and strains, comprising mixture of extracts of alder tree cones and coltsfoot leaves | A new natural herbal remedy (I), with analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity, comprises a mixture of: (a) an extract of alder tree cones and (b) an extract of coltsfoot leaves | DE20011028027 2001-06-08 | Germany |

| Medicament | Coltsfoot flower effective part with anti-influenza effect and preparation method and application | Dried coltsfoot flowers serve as raw materials, which n-butyl alcohol extract is simple in process and low in cost, and can be used for preparing drugs for preventing and treating H1N1 influenza | CN201810585765 2018-06-08 | China |

| Decoction | Traditional Chinese Medicines decoction of common coltsfoot flower for treating asthma and preparation method thereof | Comprising raw materials in parts by weight: coltsfoot flower, and radix asteris (100–300), cortex magnoliae officinalis (100–200), ginkgo seed (80–140) and rhizoma pinellinae praeparata (50–100), which has the effects of warming lung and dispelling cold and resolving sputum and relieving asthma | CN201210197598 2012-06-14 | China |

| Food therapy soup | Manufacturing method for food therapy soup of common coltsfoot flowers and lily bulbs used for cough due to dryness | An herbal nutraceutical formulation for relieving a cough, and has a certain effect on the cough due to dryness. comprising: 20 dates of red dates, 15 g of common coltsfoot flowers, 50 g of lily bulbs and a proper amount of rock sugar | CN201710372730 2017-05-24 | China |

| Herb jelly | Herb jelly, useful as parfait and food supplement, comprises mullein blossoms, stinging nettle leaves, rosemary leaves, coltsfoot, thyme, Veronica leaves, ground-ivy, sage leaves, brewing water and gelling sugar | Herb jelly comprises: mullein blossoms (3 parts), stinging nettle leaves (1 part), rosemary leaves (1 part), coltsfoot (2 parts), thyme (1 part), Veronica leaves (1 part), ground-ivy (1 part), sage leaves (2 parts), brewing water (42 Parts for processing 29 parts of brew), gelling sugar 1:1 (50 Parts), Activity: virucide | DE20072006932U 2007-05-14 | Germany |

| Flower tea | Preparing method of coltsfoot flower tea | Obtained wall-broken flower powder by a grinding method and mixed tea flowers, coltsfoot flowers, corn flowers and longan, which is nutritious, tasty and fragrant and enables the human body to absorb nutrition of the tea fully | CN20161083529 2016-02-12 | China |

| Flower powder tea | Preparation method of tea containing coltsfoot flower powder | The invention discloses a preparation method of tea containing coltsfoot flower powder, which method not only preserve the tea aroma, but also play its pharmaceutical values of moistening lungs to lower the internal heat, reducing the phlegm and stopping cough of the coltsfoot flower | CN201410562552 2014-10-19 | China |

| Beverage | Common coltsfoot flower health-care beverage | The product containing raw materials in parts by weight, coltsfoot flowers (4–5), mint (4–5), nutgrass galingale rhizomes (3–4), bighead atractylodes rhizomes (4–5) and folium isatidis (4–5), which is balanced in effect, safe, free from toxic or side effects and good in taste, and can be drunk for a long term | CN201510658241 2015-10-14 | China |

| Wine | Traditional Chinese medicines wine containing lily and common coltsfoot flower | With raw materials in parts by weight: lily (240), coltsfoot flowers (240), fritillaria cirrhosa (210) fresh ginger (180), Chinese dates (210), walnut kernels (210), almonds (80), dried radix rehmanniae (85), radix codonopsis (120), poria cocos (120), honey (200), liquor (3000). Activity: invigorating lung and kidney and relieving asthma and cough, and has obvious curative effects on symptoms of excessive phlegm, cough and asthma, lassitude in loin and legs, constipation and the like | CN201510644140 2015-09-23 | China |

| Wine | Coltsfoot flower health care wine for treatment of asthma | Taking parts of coltsfoot flower (25), ephedra rachis (15), cortex mori radices (13), Chinese angelica (16), perilla seed (14) and mangnolia officinalis (17) for washing, drying and slicing treatment etc., obtain the coltsfoot flower health care wine for treatment of the asthma | CN201210380110 2012-10-10 | China |

| Paste | Alcoholic extract pastes of common coltsfoot flower and preparation method and application thereof | After carrying out coarse grinding on common coltsfoot flower, extracting by ethanol, filtering, distilling and concentrating to prepare the alcoholic extract paste product, which can take effects of moistening lung, reducing phlegm, relieving a cough and relieving asthma in the smoking process of a patient | CN20121038413 2012-02-17 | China |

| A cosmetic composition or a food and drink | Phototoxicity inhibitor comprising extract from Tussilago farfara L. | A new and safe specific ingredient as a phototoxicity inhibitor. comprising: ≥0.07% chlorogenic acid content and ≥0.01% caffeic acid content | JP20010059727 2001-03-05 |

Japan |

4.1. Use for infection

Yakammaoto (射干麻黄汤), as a classic formula of traditional Chinese medicines, is used in the treatment of asthma, flu-like symptoms and cough with wheezing in the throat in China and Japan and is a formulation comprising nine various herbs as follows: Ephedra sinica, Pinellia ternate, Zingiber officinale, Tussilago farfara, Aster tataricus, Ziziphus jujube, Belamcanda chinensis, Asarum sieboldii, and Schisandra chinensis. The initial description of this prescription can be traced back to the prescriptions Synopsis of the Golden Chamber (Eastern Han Dynasty, written by Zhang Zhongjing A.D. 152–219), which reveals that it can be treatment of the early stage of acute asthma. To assess the effect of Yakammaoto on asthma, an experiment was performed in the OVA-induced asthma mouse model in which Yakammaoto was administered to two groups with corresponding daily doses of 2.52 and 0.63 g ml−1 through gavage. The positive control group received dexamethasone intraperitoneally injected. The results indicated that Yakammaoto can attenuate asthmatic airway hyperresponsiveness. The mechanism of the prescription may be via hindering Th2/Th17 differentiation, promoting CD4+FoxP3+ Treg generation and suppressing mTOR and NF-κB activities (Lin et al., 2020). Additionally, it has been proved that Yakammaoto is not only against flu-like symptoms but against cellular injuries in airway mucosa and renal tubular epithelia cause by Coxsackievirus B 4. An experiment was carried out in HEp-2, A549, and HK-2 cells, administering Yakammaoto (10, 30, 100, 300 μg ml−1) dose-dependently inhibited viral attachment, internalization, and replication while compared to the positive control (Yen et al., 2014). Antiviral activity against enterovirus 71 infection have also been reported (Yeh et al., 2015).

Globally, the world is scrambling to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Recently, a paper report on lung cleansing and detoxifying decoction (LCDD) widely was used in treating COVID-19 patients in China. LCDD is based on four formulae described in the classic TCMs text treatise on cold pathogenic and Miscellaneous Diseases by Zhang Zhongjing (AD 150–219) (Weng, 2020). Further investigated the buds of coltsfoot mechanism in LCDD mechanism against COVID-19 by network pharmacology and molecular docking. The resulted indicated that 14 compounds in coltsfoot may combined with SARS-CoV-2 3CL hydrolase and ACE2, thereby acting on many targets to regulate multiple signaling pathways, thus exerting the therapeutic effect on COVID-19 (Jian-xin et al., 2020).

4.2. Use for cancer

Ethnobotanical knowledge of anti-cancer medicinal plants was collected by in Estonian folk medicine. Coltsfoot was reported to be used for the management of cancer as herb tea (Sak et al., 2014). Additionally, Jerusalem Balsam,an herbal formulations, may be prepared using some raw materials which are thujones, estragole and Tussilago farfara suspected of anti-cancer activities due to their chemical constituents. Although possible formulations were reported, raw material used in this formulation was not known (Łyczko et al., 2020).

4.3. Use for vulnerary

An ethnobotanical study of vulnerary medicinal plant was collected by Jan et al. (2018) in a Catalan district. The fresh leaves of coltsfoot were reported to be used for the management of festering wounds (Rigat et al., 2015). Similarly, people of the Balkan region reported the use of coltsfoot leaves for the treatment of wound healing (Jaric et al., 2018).

5. Phytochemical aspect

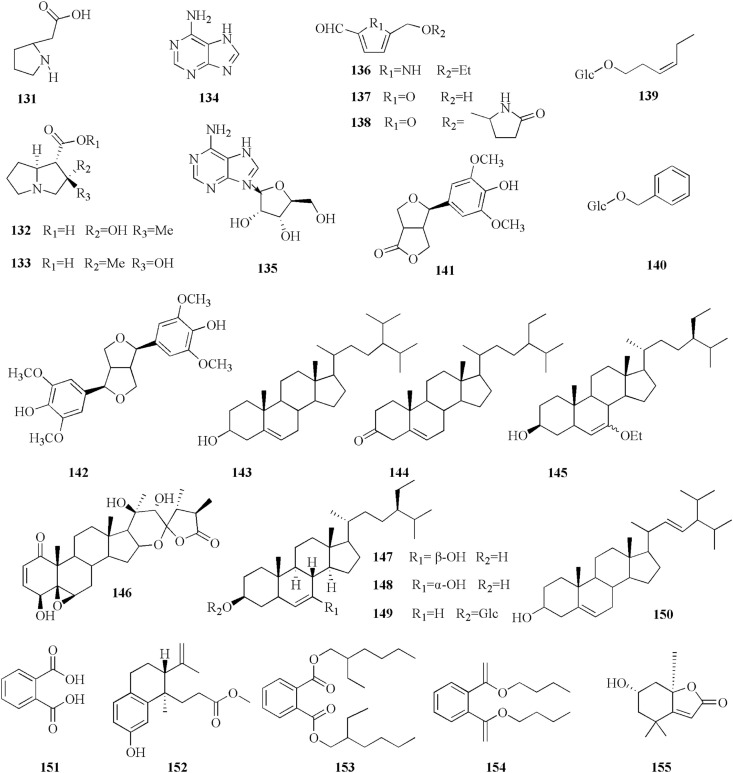

To date, approximately 150 phytochemicals have been isolated from the coltsfoot. previous studies of coltsfoot have identified the presence of chemical constituents such as sesquiterpenes (1–52), triterpenoid (53–57), flavonoids (58–70), phenolic compounds (71–95), chromones and its derivatives (96–119), alkaloids (120–130), and other phytochemicals (131–155). The phytochemicals present in coltsfoot are described in Table 3 and the structures of compounds isolated from coltsfoot are illustrated in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9 . Among these compounds, TSL (13) and caffeoylquinic acid derivatives are the main bioactive components in coltsfoot.

Table 3.

Phytochemical Constituents of coltsfoot.

| No. |

Chemical constituents |

Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Sesquiterpenes | ||

| 1 | Tussilagonone | Park et al. (2008) |

| 2 | 7β-(4-methylse-necioyloxy)-oplopa-3(14)E,8(10)-dien-2-one | Li et al. (2012) |

| 3 | 7β-senecioyloxyoplopa-3(14)Z,8(10)-dien-2-one | Yaoita et al. (2012) |

| 4 | 7β-angeloyloxyoplopa-3(14)Z,8(10)- dien-2-one | Yaoita et al. (2012) |

| 5 | 7β-[3-ethyl-cis-crotonoyloxy]-lα-[2-methylbutyryloxy]-3,14-dehydro-Z-notonipetranone | Park et al. (2008) |

| 6 | 7β-[3-ethyl-cis-crotonoyloxy]-lα-[2-methylbutyryloxy]-3,14-dehydro-E-notonipetranone | Liu et al. (2011) |

| 7 | 1α-angeloyloxy-7β-(4-methylsenecioyloxy)-oplopa-3(14)Z, 8(10)-dien-2-one | Yaoita et al. (2012) |

| 8 | 1α,7β-di(4-methyl-senecioyloxy)-oplopa-3(14)Z,8(10)-dien-2-one | Yaoita et al. (2012) |

| 9 | 1α-hydroxy-7β-(4-methylsenecioyloxy)-oplopa-3(14)Z,8(10)-dien-2-one | Li et al. (2012) |

| 10 | Farfarone D | Xu et al. (2017) |

| 11 | 7β-[3-ethyl-cis-crotonoyloxy]-lα-[3-methylvaleric]-3,14-dehydro-Z-notonipetranone | Song et al. (2019) |

| 12 | 14-acetoxy-7β-(3′-ethylcis-crotonoyloxy)-lα-(3′-methylvaleric)-notonipetranone | Song et al. (2019) |

| 13 | Tussilagone (TSL) | Kikuchi and Suzuki (1992) |

| 14 | 14(R)-hydroxy-7β-(4-methyl-senecioyloxy)-oplop-8(10)-en-2-one | Yaoita et al. (2012) |

| 15 | 14-acetoxy-7β-senecioyloxy-notonipetranone | Kikuchi and Suzuki (1992) |

| 16 | 14-acetoxy-7β-angeloyloxy-notonipetranone | Jang et al. (2016) |

| 17 | 14-acetoxy-7β-(3′-ethylcis-crotonoyloxy)-lα-(2′-methylbutyryloxy)-notonipetranone | Lim et al. (2015) |

| 18 | 14(R)-hydroxy-7β-isovaleroyloxyoplop-8(10)-en-2-one | Yaoita (2001) |

| 19 | 14(R)-acetoxy-7β-isovaleroyloxyoplop-8(10)-en-2-one | Yaoita (2001) |

| 20 | Tussfarfarin B | Liu et al. (2011) |

| 21 | 7β-angeloyloxy-14-hydroxy-notonipetranone | Li et al. (2012) |

| 22 | 7β-(3-ethyl-cis-crotonoyloxy)-14-hydroxy-1α-(2-methylbutyryloxy)-notonipetranone | Li et al. (2012) |

| 23 | 7β-(3-ethylcis-crotonoyloxy)-14-hydroxy-notonipetranone | Kikuchi and Suzuki (1992) |

| 24 | 14-acetoxy-7β-(3-ethyl-cis-crotonoyloxy)-notonipetranone | Lim et al. (2015) |

| 25 | Tussilagofarin | Jang et al. (2016) |

| 26 | Neotussilaoglactonel | (W.Shi et al., 1995) |

| 27 | β-oploplenone | Qin et al. (2014) |

| 28 | Tussilaoglactonel | Kikuchi and Suzuki (1992) |

| 29 | 1β,8-bisangeloyloxy-3α,4α-epoxybisabola-7(14),10-dien-2-one | Xu et al. (2017) |

| 30 | 1β-(3-ethyl-ciscrotonoyloxy)-8-angeloyloxy-3α,4α-epoxybisabola-7(14),10-dien-2-one | Qin et al. (2014) |

| 31 | 1α-(3-ethyl-cis-crotonoyloxy)-8-angeloyloxy-3β,4β-epoxy-bisabola-7(14),10-diene | Li et al. (2012) |

| 32 | 1α,8-bisangeloyloxy-3β, 4β-epoxy-bisabola-7(14),10-diene | Li et al. (2012) |

| 33 | 8-angeloylxy-3,4-epoxy-bisabola7(14),10-dien-2-one | Park et al. (2008) |

| 34 | (1R,3R,4R,5S,6S)-1-acetoxy-8-angeloyloxy-3,4-epoxy-5-hydroxybisabola-7(14),10-dien-2-one | Qin et al. (2014) |

| 35 | (1R,3R,4R,5S,6S)-1,5-diacetoxy-8-angeloyloxy-3,4-epoxybisabola-7(14),10-dien-2-one | Qin et al. (2014) |

| 36 | (3R,4R,6S)-3,4-epoxybisabola-7(14),10-dien-2-one | Li et al. (2012) |

| 37 | 1α,5α-Bisacetoxy-8-angeloyloxy-3β,4β-epoxy-bisabola-7(14),10-dien-2-one | Ryu et al. (1999) |

| 38 | Tussfararin A | Qin et al. (2014) |

| 39 | Tussfararin B | Qin et al. (2014) |

| 40 | Tussfararin C | Qin et al. (2014) |

| 41 | Altaicalarin C | Song et al. (2019) |

| 42 | Farfarone B | Xu et al. (2017) |

| 43 | Farfarone A | Xu et al. (2017) |

| 44 | Tussfararin D | Qin et al. (2014) |

| 45 | Tussfararin E | Qin et al. (2014) |

| 46 | Tussfararin F | Qin et al. (2014) |

| 47 | (4R,6E)-2-acetoxy-8-angeloyloxy-4-hydroxybisabola-2,6,10-trien-1-one | Qin et al. (2014) |

| 48 | (−)-cryptomerion | Qin et al. (2014) |

| 49 | (9S)-altaicalarin B | Liu et al. (2011) |

| 50 | (−)-spathuleno | Yaoita (2001) |

| 51 | Ligucyperonol | (Kang et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2017) |

| 52 | Tussfarfarin A | Liu et al. (2011) |

| Triterpenoids | ||

| 53 | Arnidiol | Santer and Stevenson (1962) |

| 54 | Faradiol | Santer and Stevenson (1962) |

| 55 | Bauerenol | Yaoita et al. (2012) |

| 56 | Isobauerenol | Yaoita et al. (2012) |

| 57 | Bauer-7-ene-3β,16α- diol | Yaoita et al. (2012) |

| Flavonoids | ||

| 58 | Apigenin | Hleba et al. (2014) |

| 59 | Luteolin | Hleba et al. (2014) |

| 60 | Quercetin | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 61 | Quercetin 3-O-β-L-arabinopyranoside | Kim et al. (2006) |

| 62 | Quercetin 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Kim et al. (2006) |

| 63 | Hyperoside | Yang et al. (2019) |

| 64 | Rutin | Gao et al. (2008) |

| 65 | Kaempferol | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 66 | Kaempferol-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 67 | Kaempferol-3-O-β- D-glucopyranoside | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 68 | Kaempferol-3-O-β-D-galactopyranoside | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 69 | Kaempferol-3-O-[3,4-O-(isopropylidene)-α-L-arabinopyranoside | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 70 | Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside | Yang et al. (2019) |

| phenolic conpounds | ||

| 71 | Benzoic acid | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| 72 | P- Hydoxybenzoic acid | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| 73 | Syringic acid | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| 74 | Gallic acid | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| 75 | 4-hydroxyacetophenone | Kang et al. (2016) |

| 76 | 4-hydroxybenzoic acid | Kang et al. (2016) |

| 77 | Trans-cinnamic acid | Kang et al. (2016) |

| 78 | Ferulic acid | Liu et al. (2007b) |

| 79 | Isoferulic acid | Liu et al. (2007b) |

| 80 | P-coumaric acid | Zhao et al. (2014) |

| 81 | Sinapic acid | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| 82 | Caffeic acid | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 83 | Chlorogenic acid | Wu et al. (2016) |

| 84 | Cryptochlorogenic acid | Yang et al. (2019) |

| 85 | Neochlorogenic acid | Yang et al. (2019) |

| 86 | Methyl 3-O-caffeoyl quinate | (Liu, Y.F. et al., 2007) |

| 87 | Methyl 4-O-caffeoyl quinate | (Liu, Y.F. et al., 2007) |

| 88 | 3,4-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 89 | Methyl 3,4-di-O-caffeoylquinate | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 90 | 3,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 91 | Methyl 3,5-di-O-caffeoylquinate | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 92 | 4,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 93 | Methyl 4,5-di-O-caffeoylquinate | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 94 | 4,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid butyl ester | Yang et al. (2018) |

| 95 | Rosmarinic acid | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| Chromones and its stereoisomers | ||

| 96 | 6-methoxy-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-ol (S) | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 97 | 6-methoxy-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-ol (R) | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 98 | 6-acetyl-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-one (S) | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 99 | 6-acetyl-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-one (R) | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 100 | 2,2-dimethyl-6-(1-hydroxyethyl) (S)- chroman-4-one | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 101 | 2,2-dimethyl-6-(1-hydroxyethyl) (R)- chroman-4-one | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 102 | 6-(1-methoxyethyl) (R)-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-ol (S) | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 103 | 6-(1-methoxyethyl) (S)-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-ol (R) | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 104 | 6-(1-methoxyethyl) (S)-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-ol (S) | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 105 | 6-(1-methoxyethyl) (R)-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-ol (R) | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 106 | 6-(1- ethoxyl) (R)-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-ol (S) | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 107 | 6-(1- ethoxyl) (S)-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-ol (R) | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 108 | 6-(1- ethoxyl) (S)-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-ol (S) | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 109 | 6-(1- ethoxyl) (R)-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-ol (R) | Sun et al. (2019) |

| 110 | 6-acetyl-7-hydroxy-2,3-dimethylchromone | Xu et al. (2017) |

| 111 | 6-carboxyl-7-hydroxy-2,3-dimethylchromone | Wu et al. (2008) |

| 112 | 6-(1-Ethoxyethyl)-2,2- dimethylchroman-4-ol | Liu et al. (2011) |

| 113 | 6-hydroxy-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-one | Jang et al. (2016) |

| 114 | 1-(4-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-chroman-6-yl)-ethanone | Jang et al. (2016) |

| 115 | 2,2-dimethyl-6-(1-hydroxyethyl)- chroman-4-one | Jang et al. (2016) |

| 116 | 6-(1-hydroxyethyl)-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-ol | Jang et al. (2016) |

| 117 | 6-acetyl-2,2-dimethylchroman-4-one | Jang et al. (2016) |

| 118 | 1-[(4S)-3,4-dihydro-4-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-2H-1-benzopyran-6-yl]-ethanone | Kang et al. (2016) |

| 119 | Tussilagofarol | Jang et al. (2016) |

| Alkaloids | ||

| 120 | 2-{[(2S)-2-Hydroxypropanoyl]amino}benzamide | Yang et al. (2018) |

| 121 | Tussilagine | Roder et al. (1981) |

| 122 | Tussilaginine | Pabreiter (1992) |

| 123 | Isotussilagine | Pabreiter (1992) |

| 124 | Neo-tussilagine | Pabreiter (1992) |

| 125 | Neo-isotussilagine | Pabreiter (1992) |

| 126 | Senkirkine | Nedelcheva et al. (2015) |

| 127 | Senecionine | Nedelcheva et al. (2015) |

| 128 | Integerrimine | Nedelcheva et al. (2015) |

| 129 | Seneciphylline | Nedelcheva et al. (2015) |

| 130 | Senecivernine | Kopp et al. (2020) |

| Other phytochemicals | ||

| 131 | 2-pyrrolidineactic acid | Pabreiter (1992) |

| 132 | Tussilaginic acid | Pabreiter (1992) |

| 133 | Isotussilaginic acid | Pabreiter (1992) |

| 134 | Adenine | Zhi et al. (2012) |

| 135 | Adenosine | Zhi et al. (2012) |

| 136 | 3β-hydroxy-7α-ethoxy-24β-ethylcholest-5-ene 4 | Liu et al. (2011) |

| 137 | 2-formyl-5-hydroxymethyl-furan | Liu et al. (2011) |

| 138 | Sessiline | Liu et al. (2011) |

| 139 | Hex-3-en-1-ol 1-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 140 | Benzyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | Kuroda et al. (2016) |

| 141 | Glaberide I | Jang et al. (2016) |

| 142 | Syringaresinol | Jang et al. (2016) |

| 143 | β-sitosterol | Zhi et al. (2012) |

| 144 | Sitosterone | Zhi et al. (2012) |

| 145 | 5-ethoxymethyl-1H-pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde | Liu et al. (2011) |

| 146 | Ixocarpalactone B | Yang et al. (2018) |

| 147 | 7β-hydroxysitosterol | Liu et al. (2007b) |

| 148 | 7α-hydroxysitosterol | Liu et al. (2007b) |

| 149 | Daucosterol | Liu et al. (2007b) |

| 150 | Stigmasterol | Liu et al. (2007b) |

| 151 | Phthalic acid | Liu et al. (2007b) |

| 152 | Moluccanic acid methyl ester | Liu et al. (2007b) |

| 153 | Bis (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate | Liu et al. (2007b) |

| 154 | Dibutylphthalate | Liu et al. (2007b) |

| 155 | Loliolide | Zhao et al. (2014) |

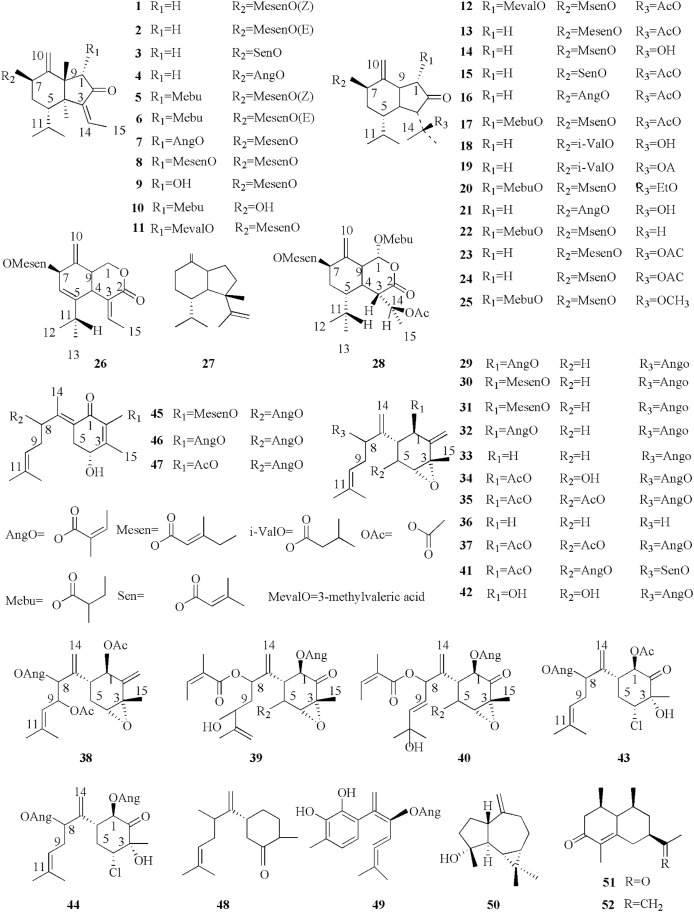

Fig. 3.

The sesquiterpenoids compounds isolated from coltsfoot.

Fig. 4.

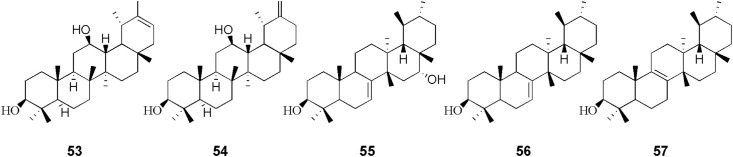

The triterpenoid isolated from coltsfoot.

Fig. 5.

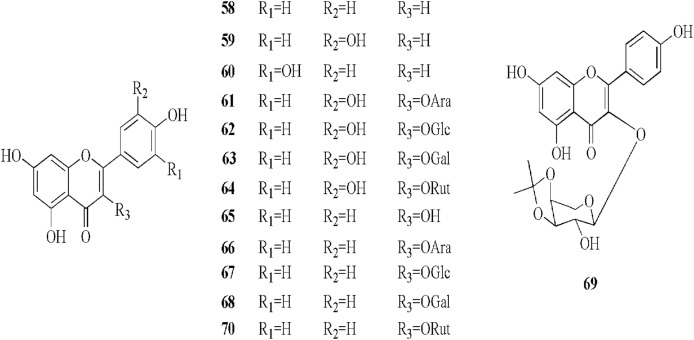

The flavonoids and flavonoid glycosides isolated from coltsfoot.

Fig. 6.

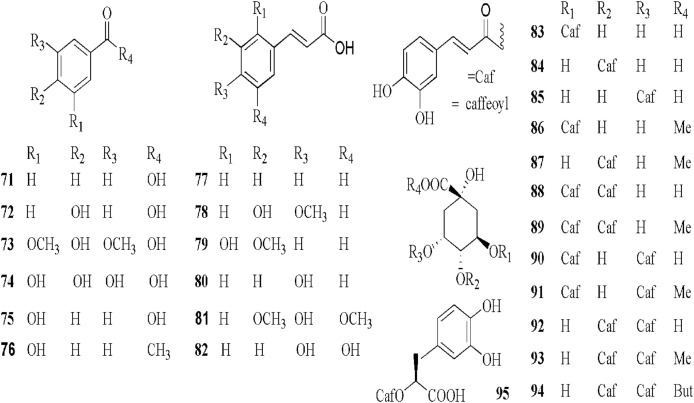

The phenolic compounds isolated from coltsfoot.

Fig. 7.

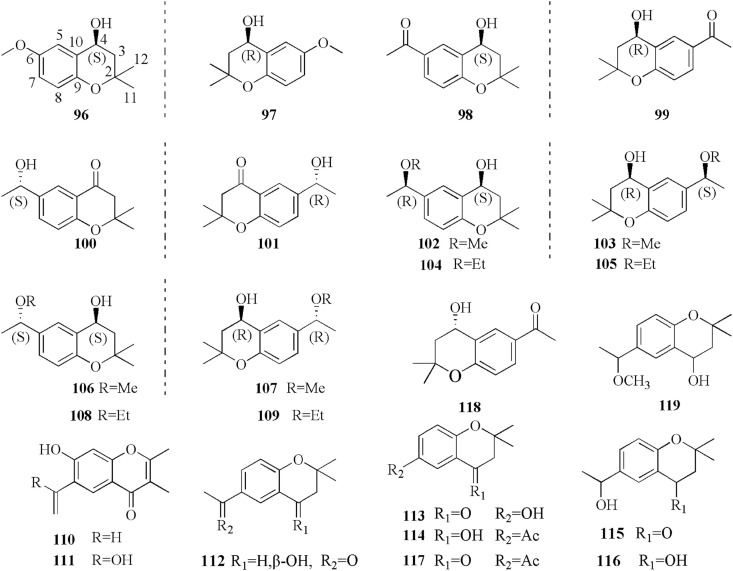

The chromones and its derivatives isolated from coltsfoot.

Fig. 8.

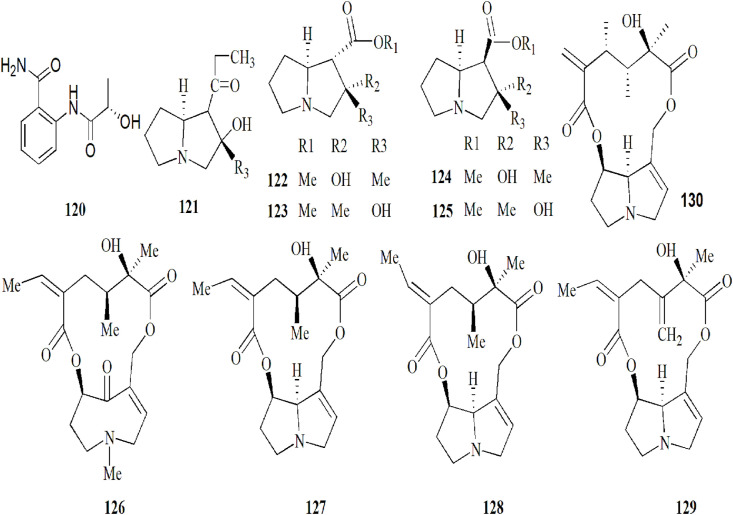

The alkaloids isolated from coltsfoot.

Fig. 9.

The other phytochemical compounds isolated from coltsfoot.

5.1. Sesquiterpenes

Previous phytochemical investigations revealed that sesquiterpenoids contained oplopane (1–28) and bisabolane (29–49), the skeletons of which are substituted with diverse ester derivatives (Song et al., 2019). Recently, some novel sesquiterpenoids have been reported such as bisabolane-type tussfararins A–F (38–40, 45, 46) (Qin et al., 2014), farfarone B- A (42–43) and farfarone D (10) (Xu et al., 2017), an oplopane-type sesquiterpene skeleton. In addition, three novel sesquiterpenoids were separated by Song et al. (2019), bearing an unreported substituent for the first time. Among these compounds, altaicalarin C (41) was first reported from Ligularia altaica and (11, 12) first seen in nature (Song et al., 2019). As well as, eudesmane skeletons and a bicyclic norsesquiterpenoid were also identified, including, (−)-spathuleno (50), ligucyperonol (51), and tussfarfarin A (52), one new norsesquiterpenoid. Additionally, total seven substituents have been reported on several studies (Jang et al., 2016; Li et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2011; Park et al., 2008; Qin et al., 2014; Song et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2017). The structures (1–52) are listed in Fig. 3.

5.2. Triterpenoid

After isolating arnidiol (53) and faradiol (54) from the flower buds of coltsfoot (Santer and Stevenson, 1962),bauer-7-ene-3β,16α-diol (57), a bauerane-type triterpenoid has also been isolated from this plant, along with bauerenol (55) and isobauerenol (56) (Yaoita et al., 2012). The structures (53–57) are shown in Fig. 4. However, in recent years researches were carried out extensively the review of sesquiterpenes but few triterpenoids.

5.3. Flavonoids

Until now, a total of 13 flavonoids and flavonoid glycosides have been isolated from coltsfoot.

Hleba et al. (2018) isolated apigenin (58) and luteolin (59) from the extract of the flowers and stems of coltsfoot collected from Slovakia. The compound were identified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Hleba et al., 2014). Recently, the methanol (MeOH) extracts of the leaves of coltsfoot have been reinvestigated and afforded flavonoids, such as kaempferol (65), kaempferol 3-O-[3,4-O-(isopropylidene)--Larabinopyranoside (66), as an isopropylidene derivative of kaempferol 3-O-L-arabinopyranoside (67), kaempferol 3-O- D-glucopyranoside (68), kaempferol 3-O-D-galactopyranoside (69), quercetin (60). Among them, (66, 67 and 69) were demonstrated from coltsfoot for the first time (Kuroda et al., 2016). Flavonoids from coltsfoot are usually enzyme assay-guided fractionation of the extract and elucidated based on MS and NMR data (Kuroda et al., 2016). Additionally, a phytochemical investigation using a bioassay-guided chromatographic separation technique led to the isolation of two flavonoid glycosides, namely quercetin 3-O-β-L-arabinopyranoside (59) quercetin 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (60) (Kim et al., 2006). Furthermore, rutin (64) has been identified in the MeOH extract of flower buds of coltsfoot by MS data and comparison of the NMR data analysis (Gao et al., 2008). Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside (70) (Yang et al., 2019) and hyperoside (63) (Seo et al., 2015) have also been identified in flower buds of coltsfoot. The structures (58–70) are listed in Fig. 5.

5.4. Phenolic compounds

The phenolic compounds, phenylmethane derivatives (71–76), phenylpropane derivatives (77–81) and esters of phenylpropanoic acids (82–95), have also been identified in coltsfoot.

The aerial parts of coltsfoot from Kastamonu, Turkey afforded benzoic acid (71) p- Hydoxybenzoic acid (72), syringic acid (73) and gallic acid (74) using reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography technique (Uysal et al., 2018). However, the authors did not isolate and elucidate those compounds by chromatographic, mass spectrometric and NMR spectroscopic techniques. Additionally, The MeOH extract of the dried flower buds of coltsfoot afforded two phenylmethane derivatives by comparison of their physical and spectroscopic data with the present literature including 4-hydroxyacetophenone (75) and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (76) (Kang et al., 2016).

The phenylpropane derivatives and esters of phenylpropanoic acids were separated and purified by different chromatographic methods and their structures were elucidated by IR, MS and 1H and13C NMR data (Kang et al., 2016; Kuroda et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Yang Liu et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2007a; Wang et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2014; Zhi et al., 2012). It is worth noting that for exploring the isomers of phenolic acids by UPC2 is efficient (Wang et al., 2019). The total phenolic acid and individual phenolic of EtOAc, Water and MeOH extracts of coltsfoot collected from Kastamonu, Turkey were determined by using well established procedures such as Folin–Ciocalteu tests and an HPLC-DAD technique. The results showed that the highest amount of total phenolics of the aerial parts in MeOH extract were 84.54 mg/g as gallic acid equivalents (GAE). Interestingly, a high amount of chlorogenic acid (2940 μg/g extract) (83) and rosmarinic acid (2722 μg/g extract) (95) in water extracts rather than in MeOH. However, the authors did not isolate and elucidate compounds 83 and 95 by mass spectrometric and NMR spectroscopic techniques (Uysal et al., 2018). Norani et al. (2019) reinvestigation seven major regions of Iran found that the Nur's region had the highest total phenolic involved in 278.2 mg GAE/g dry weight of leaves MeOH extracts. The authors also indicated that the content of total phenols was positively correlated with the antioxidant activity of the extracts (Norani et al., 2019).

The structures of these compounds (71–95) are shown in Fig. 6.

5.5. Chromones and its derivatives

Wu et al. (2008) identified two chromones for the first time in coltsfoot, namely, (110) and (113) (Wu et al., 2008). Subsequently, Liu et al. (2011) investigated the petroleum ether extractives of the flower buds of coltsfoot by extensive spectroscopic analysis. Compounds were identified as chromones, including (112–114, 117) (Liu et al., 2011). The MeOH layer of the n-hexane fraction of flower buds of coltsfoot, collected in Korea yielded a new chromone tussilagofarol (119), in addition to (115, 116) (Jang et al., 2016).

Importantly, a series of chromane enantiomers have been reported, such as 1-[(4S)-3,4- dihydro-4-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-2H-1-benzopyran-6-yl]-ethenone (118), a novel cytoprotective compound (Kang et al., 2016). In a previous study, Sun et al. (2019) investigated the intensive phytochemicals of the flower buds MeOH extracts of coltsfoot by detailed spectroscopic analyses, chemical methods. The compounds were identified as chromane derivatives of seven pairs of enantiomers (96–109) (Fig. 7 .) (Sun et al., 2019). Although there is currently limited evidence to the activities of these stereoisomers, they might be significant chemical markers of coltsfoot (Sun et al., 2019). The structures 96–119 are listed in Fig. 7.

5.6. Alkaloids

To date, in all 10 PAs have been reported in coltsfoot, which was notably known for senkirkine (126) and senecionine (127) that have been receiving increasing attention because of their toxic reactions in humans (Moreira et al., 2018; Nedelcheva et al., 2015). As well as, Nedelcheva et al. (2015) also identified two PAs named, seneciphylline (129) and integerrimine (128) by gas chromatography and mass spectrometry analysis (Nedelcheva et al., 2015). Senecivernine (130) was quantified by HPLC-MS/MS and pressurised liquid extraction (Kopp et al., 2020). The authors concluded that this approach can be used to the complete and automated extraction of pyrrolizidine alkaloids (Kopp et al., 2020). Tussilagine (121), another PAs, has been isolated and identified in flowers of coltsfoot by HILIC/ESI-QTOF-MS and HPTLC (Smyrska-Wieleba et al., 2017). In a previous study, tussilaginine (122), isotussilagine (123), neo-tussilagine (124) and neo-isotussilagine (125) were also isolated and identified in this plant (Pabreiter, 1992). The structures 120–130 are listed in Fig. 8.

5.7. Volatile oils

Norani et al.(2019)have been identified and quantified essential oil from seven major regions of Iran. The results indicated that coltsfoot has a relatively low yield of volatile oils, especially in leaves (Norani et al., 2019).

Additionally, Liu et al. (2006) identified the chemical constituents of the essential oil from the buds of coltsfoot from China (Liu et al., 2006). Sixty-five components were characterized in the essential oil, representing 84. 62% of the total volatile oil (Liu et al., 2006).

Judzentiene et al. (2011) analyzed the volatiles composition of flower and rachis of coltsfoot from Lithuania. Totally sixty-five volatile components belonging to different chemical classes were identified. The authors concluded that there is variability in coltsfoot essential oil composition (Judzentiene and Budiene, 2011).

Furthermore, Boucher et al. (2018) identified the chemical constituents of the essential oil from the flowers collected from Quebec, Canada of coltsfoot by GC-FID/GC-MS. Forty-five components were characterized in the essential oil. Interestingly, the authors concluded that there is variability in coltsfoot essential oil composition (Boucher et al., 2018).

5.8. Other phytochemicals

Other metabolites belonging to coltsfoot, including sterols, amino acids, organic acid (Zhi et al., 2012) and polysaccharides have also been documented in the coltsfoot (Safonova et al., 2018b). A chemical investigation of the MeOH extracts of coltsfoot leaves by enzyme assay-guided fractionation of the extract resulted in the isolation of two glucosinates, (139 and 140) for the first time (Kuroda et al., 2016). Of particular interest is the noteworthy this plant contained significant levels of trace metals (such as Zn, Mg and Se) which are likely to be responsible for their activities (Ravipati et al., 2012; Wechtler et al., 2019). The structures (131–155) are listed in Fig. 9.

6. Pharmacology

There are some biological activities in the extracts or compounds of coltsfoot. Anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, antiviral and anti-cancer are similar with traditional uses. In addition, many new biological activities have been discovered in modern research, such as anti-diabetic, neuro-protective activities, immunostimulating activities, anti-oxidant activity and cardiovascular. These biological activities are described in the table (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 ) and briefly described in below.

Table 4.

Example of Anti-inflammatory activity potential of coltsfoot.

| Assay | Solvent/components | Model, method | Concentration/Dosage | Positive control | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-inflammatory | TGN (1) | IMQ-induced psoriatic skin lesions in HaCaT keratinocytes (in vitro/vivo) | TGN (1 or 5 nmol/100 μl) | CAL SFN and tBHQ | ↓ NF-κB and STAT3 and psoriasis-associated markers via Nrf2 activation | (Lee, J. et al., 2019) |

| Anti-inflammatory | TGN (1) | LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced skin inflammation in mice (in vitro/vivo) | TGN (2.5,5 and 10 μM) LPS (1 μg ml−1) | Dexamethasone (5 μM in 0.2 mL DMSO/acetone) | TGN (2.5 and 5 μM) reduced iNOS and COX-2 expression and ↑ Nrf2/HO-1 and ↓ NF-κB signaling pathway, similar to dexamethasone (5 μM) | Lee et al. (2016) |

| Anti-inflammatory | L-652,469(24) | Carrageenan-induced rat hindpaw edema, PAF-induced rat foot edema (in vitro/vivo). |

15–50 mg kg−1 p.o. 50,100 mg p.o. | Nitrendipine | ↓the PAF-induced rat foot edema and the first phase of carrageenan-induced rat hindpaw edema. | Hwang et al. (1987) |

| Anti-inflammatory | TSL (13) | DSS-induced acute colitis mice (in vivo) | TSL (0.5 or 2.5 mg kg−1) | without DSS | Attenuated weight loss, colon shortening and severe clinical signs ↓ the activation of NF-κB and inducing Nrf2 pathways | Cheon et al. (2018) |

| Anti-inflammatory | TSL (13) | LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells CLP-Induced Septic Mice (in vitro/vivo) | TSL (10,20,30 μM) TSL (1,10 mg kg−1) | No treatment | ↓ expression of COX-2 and TNF-α in PAM and serum level of NO, PGE2, TNF-α and HMGB1↓ MAP Kinases and NF-κB | Kim et al. (2017) |

| Anti-inflammatory | TSL (13) | The induction of HO-1 in murine macrophages (in vitro) | TSL (0–30 μM) LPS (1 μg ml−1 | α-tubulin | TSL-induced HO-1 protein expression in a dose- and time-dependent manner without the induction of HO-1 mRNA expression | Hwangbo et al. (2009) |

| Anti-inflammatory | TSL (13) | LPS-activated BV-2 cells (in vitro) | TSL (5,10 μg ml−1) TSL (2–30 μM) | LPS-media | Dose-dependent ↓ NO and PGE2 production with IC50 values of 8.67 μM, 14.1 μM, respectively, for neuro-inflammatory diseases | Lim et al. (2008) |

| Anti-inflammatory | 70% ethanol buds) | Brain ischemia was induced in Sprague-Dawley rats (in vivo), BV2 cells (in vitro) | TF (300 mg kg−1 P.O.) | MK-801(i.p) 1 mg kg−1 | ↓ the neuronal death and the microglia/astrocytes activation in ischemic brains, also ↓ cytokines | Hwang et al. (2018) |

Notes.

↑: activated, ↓: inhibition, TF, Tussilago farfara L.; HO-1, Heme oxygenase-1; dextran sulfate sodium; SFN, Sulforaphane; tBHQ, tert-butylhydroquinone; CAL, Calcipotriol hydrogen peroxide; TPA:12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate; IMQ, imiquimod; NF-κ B: nuclear factor-kappa B; Nrf2: nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2; NO: nitric oxide.

Table 5.

Example of anticancer (anti-proliferation) potential of coltsfoot.

| assay | Solvent/components | Model/method | Concentration/Dosage | Positive control | Findings | Reference | |

| Anti-cancer | Sesquiterpenoids (flower bud) | Three cancer cell lines (AGS, HT-29 and PANC-1) | (50.0,25.0, 12.5,6.25, 3.12 μM) Au or Ag | N/d | The IC50 values of PANC-1 cells were the lowest: 166.1 μM Ag for TF-AgNPs and 71.2 μM Au for TF-AuNPs | Lee et al. (2019b) | |

| Anti-cancer | MeOH fraction (leaves, rachis) | Co-treatment of Huh7 cells with TF and TRAIL induced apoptosis (in vitro) | TF (200 μg ml−1) and TRAIL (100 ng ml−1) | DMSO 0.1% (v/v). | ↓ inhibition of the MKK7-TIPRL interaction and ↑ in MKK7/JNK phosphorylation | Lee et al. (2014) | |

| Anti-cancer | 55% acetonitril ECN (5) | TNBC MDA-MB-231 Cells (in vitro) TNBC Female BALB/c nude mice (in vivo) | ECN (0–15 μ M) ECN (1 mg kg−1) |

Staurosporine (IC50 = 0.3 μM) | ↓ the JAK–STAT3 signaling pathway and the expression of STAT3 target genes inducing apoptosis of TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells (IC50 = 3.27 μg ml−1) | Jang et al. (2019) | |

| Anti-proliferation | TSL (13) | SW480 and HCT116 colon cancer cell lines (in vitro) | TSL (2,10, and 30 μM) | DMSO | ↓ the β-catenin activity and ↓the expression of target genes of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway dose dependently | Li et al. (2014) | |

| anti-angiogenesis | TSL (13) | HUVEC (in vitro) VEGF-induced angiogenesis (In vivo) | TSL (3, 10, and 30 μM), TSL (1 and 10 mg kg−1) | Cabozanitib (XL184) (5 μM) (30 mg kg−1) | Anti-proliferation via ↓ VEGFR2 signaling pathway and 30 μM (TSL) more effect than cabozanitib (5 μM) ↓ endothelial cell proliferation, migration, tube formation and angiogenesis |

Li et al. (2019) | |

| Anti-cancer | Polysaccharides (TFPB1) | A549 human non-small lung cancer cell line (in vitro) | TFPB1 (0–1000 μg ml−1) | N/d | In a dose-dependent manner anti-proliferative and anti-apoptotic effect via modulated by the downregulation of PI3K/Akt pathway | Qu et al. (2018) | |

Notes.

↑Activated, ↓Inhibition, N/d, no date; TF, Tussilago farfara L.; AgNPs, silver nanoparticles; AuNPs, gold nanoparticles; HUVEC, tube formation of primary human umbilical vascular endothelial cell; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; AGS, human gastric adenocarcinoma cell; HT-29, human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell; PANC-1, human pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma cell; TNBCs, Triple-negative breast cancers; MDA-MB-231, Human Breast Cancer Cells; MKK7, mitogen protein kinase kinase 7; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; TIPRL, TOR signaling pathway regulator-like protein; STAT3, Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; JAK, Janus kinase.

Table 6.

Examples of antimicrobial screening conducted on different Parts of Tussilago farfara L. (coltsfoot).

| Assay | Plant part | Solvent/extracts | Test method and organisms/virus | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibacterial | Flower bud | n-hexane-acetonitrile-water | In vitro by MIC method and screen against twenty (20) strains of both G- and G+ | Better activity TF-AgNPs (two to four-fold enhancement) than the extract alone | Lee et al. (2019b) |

| Antibacterial | Flowers | Essential oil, dodecanoic acid | In vitro MIC method and screen against E. coli and S. aureus. | Essential oil antibacterial activity against E. coli (MIC50 = 468 μg ml−1) S. aureus (MIC50 = 368 μg ml−1) | Boucher et al. (2018) |

| Antibacterial | Leaf | EtOAc, MeOH, Water | In vitro by MIC method and screen against G-: E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. typhimurium and G+: L. monocytogenes, E. faecalis, B. cereus, M. flavus and S. aureus. | Inhibitory effect the MIC and the MBC ranged from 0.06 mg ml−1 to 0.40 mg ml−1, 0.124 mg ml−1 to 0.45 mg ml−1 respectively | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| Antibacterial | Flowers and rachis | MeOH | In vitro MIC method and screen against six (6) strains in vitro microdilution method and screen against six (6) strains G-: E. coli, S. rubidaea, P. aeruginosa.G+: L. rhamnosus, S. epidermis, E. raffinosus. | Antimicrobial antibacterial activity with MIC50 = 48.01–64 μg ml−1 for five (5) and small antibacterial activity with MIC50 = 191.85 μg ml−1 for S. epidermis | Hleba et al. (2014) |

| Antibacterial | Leaves | Water | In vitro agar diffusion method and screen against six (6) Strains: G-:K. pneumonia, E. coli, P. aeruginosa,G+:S. epidermidis, S. aureus, S. pyogenes | Inhibition zone ranged from 16.4-17.3 mm with inhibitory effect against G+ and antibacterial activity with G- (0–12.4 mm) | Turker and Usta (2008) |

| Antibacterial | Flowers | Water | In vitro agar diffusion method and screen against six (6) Strains: G-:K. pneumonia, E. coli, P. aeruginosaG+:S. epidermidis, S. auerus, S. pyogenes | Antibacterial activity with inhibition zone ranged from 0 - 9.6 mm | Turker and Usta (2008) |

| Antibacterial | Aerial part rhizome | MeOH | In vitro MIC method and screen against four (4) strains: B. cereus, E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa | Antibacterial activity with MIC = 15.63 and 62.5 mg of dry plant material ml−1 for B. cereus and S. aureus, respectively | Kokoska et al. (2002) |

| Antifungal | Leaf | EtOAc, MeOH, and water |

In vitro by MIC method and screen against eight (8) antifungal strains: A. versicolor, A. fumigatus, A. ochraceus, A. niger, P. ochrochloron, P. funiculosum, P. verrucosum and T. viride |

Antifungal activity (MIC = 0.3–0.4 mg ml−1),compared to the positive control Bifonazole and Ketoconazole (MIC = 0.1–0.2 mg ml−1, MFC: 0.2–1.5 mg ml−1) | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| Yeast | Flowers and rachis | MeOH | In vitro MIC method and screen against S. cerevisiae | Antimicrobial activity against S. cerevisiae with a MIC50 value of 24 μg ml−1 | Hleba et al. (2014) |

| Antitubercular | Aerial parts | EtOAc n-hexane | In vitro MIC method for activity against mycobacterium tuberculosis and to isolate and identify the compounds responsible for this reputed anti-TB effect | The best activity was observed for p-coumaric acid (80) (MIC = 31.3 μg ml−1L or 190.9 μM) alone | Zhao et al. (2014) |

| Anti-viral activity | Aerial parts | Hot water | In vitro both CCFS-1/KMC and RD cell lines by enterovirus 71-Induced | CCFS-1/KMC (IC50 = 106.3 μg ml−1); RD cells (IC50 = 15.0 μg ml−1) inhibit EV71 infection by preventing viral replication and structural protein expression | Chiang et al. (2017) |

Notes.

TF-AgNPs, Tussilago farfara L. silver nanoparticles; MIC, the minimal inhibitory concentration; MBC, minimum bactericidal concentrations; IC50, the minimal concentration required to inhibit 50% cytopathic effect; G-: Gram negative bacteria; G+: Gram-positive bacteria; CCFS-1/KMC, human foreskin fibroblast; RD, human rhabdomyosarcoma.

Table 7.

Chemical antioxidant screening of coltsfoot.

| Assay-type | Solvent/extracts | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIA | Crude polysaccharides, polysaccharides | The IC50 value ascorbic acid < polysaccharides < crude polysaccharides | (Qin, K. et al., 2014) |

| Yeast | Water extracts | 20.9 inhibition of Yeast oxidation | Ravipati et al. (2012) |

| DPPH | MeOH extract | IC50 = 5 μg ml−1 while positive control BHT was 33 μg ml−1 | Norani et al. (2019) |

| DPPH | EtOAc MeOH Water | 28.79 mg TE/g extract DW | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| 192.35 mg TE/g extract DW | |||

| 183.19 mg TE/g extract DW | |||

| DPPH | Water extracts | 198.9 μM Ascorbate equivalent/g | Ravipati et al. (2012) |

| Ethanol extracts | 113.5 μM Ascorbate equivalent/g | ||

| ABTS | EtOAc extracts | (41.08 mg TE/g extract DW | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| MeOH extracts | (410.98 mg TE/g extract DW | ||

| Water extracts | (399.18 mg TE/g extract DW | ||

| ABTS | Phenolic content 30.03 mg GAE/g DW | 217.62 μM Trolox/g DW | Song et al. (2010) |

| FRAP | Phenolic content 30.03 mg GAE/g DW | 455.64 μM Fe2+/g DW | Song et al. (2010) |

| FRAP | EtOAc extracts | (49.98 mg TE/g extract DW | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| MeOH extracts | (465.31 mg TE/g extract DW | ||

| Water extracts | (380.25 mg TE/g extract DW | ||

| CUPRAC | EtOAc extracts | (93.78 mg TE/g extract DW | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| MeOH extracts | (677.09 mg TE/g extract DW | ||

| Water extracts | (453.38 mg TE/g extract DW | ||

| Phosphomolybdenm | EtOAc extracts | (1.54 mg TE/g extract DW | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| MeOH extracts | (2.26 mg TE/g extract DW | ||

| Water extracts | (1.44 mg TE/g extract DW | ||

| Metal chelating | EtOAc extracts | (13.11 mg EDTAE/g DW | Uysal et al. (2018) |

| MeOH extracts | (6.16 mg EDTAE/g DW | ||

| Water extracts | (4.98 mg EDTAE/g DW | ||

| NBT | EtOAc extract | IC50 = 1.8 μg ml−1 | Kim et al. (2006) |

| NBT | Quercetin-3-O-β-L-arabinopyranoside Quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside |

IC50 = 12.9 μM | Kim et al. (2006) |

| IC50 = 35.6 μM | |||

| while quercetin IC50 = 63.9 μM |

Notes.

ABTS, 2:2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline)-6-sulfonic acid.

BHT, a synthetic industrial antioxidant.

DPPH, 1:1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl.

DW, dry weight.

EDTAE, EDTA equivalents.

FIA, a flow injection analysis method.

FRAP, ferric reducing antioxidant power.

GAE, gallic acid equivalent; dry weight DW.

IC50, inhibitory concentration at 50% level.

TE, trolox equivalents.

6.1. Anti-inflammation

Several studies have assessed the anti-inflammation activity of coltsfoot, which can be categorized as preliminary (in vitro/vivo-based).

TGN (1), a sesquiterpenoid isolated from coltsfoot, have been evaluated as a potential treatment against psoriasis that is a common inflammatory skin disorder (Lee, J. et al., 2019) (Table 4).

Additionally, the biological analysis showed that 41 sesquiterpenoids inhibited NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells with IC50 values rang 3.5 μM from 60.29 μM (Jang et al., 2016; Li et al., 2012; Qin et al., 2014). Further mechanism studies indicated that TSL (13) and its allied were evaluated for the anti-inflammation activity, with in vivo/vitro model, such as a CLP-induced mouse model of sepsis, having been used (Table 4).

Moreover, Wu et al. (2016) investigated a mixture of four compounds isolated from flower buds, (83:90: 88:92) (5:28:41:26), for its anti-inflammation, antitussive and expectorant activities in mice with the ammonia liquor-induced and the phenol red secretion. Subsequently, the authors suggested that the compound 4,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid (92) showed the strongest effect to inhibit the leucocytosis by 49.7%, and they may act in a collective and synergistic way. However, the mechanism of the action requests further investigation (Wu et al., 2016).

6.2. Neuro-protective activity

The potential of coltsfoot to enhance human memory and prevent acute and chronic neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and stroke has been reported.

Cho et al. (2015) examined the effects of different concentrations (0.1–30 μg ml−1) of the EtOAc fraction from coltsfoot, which has shown to significantly inhibit various types of neuronal cell damage in cortical cells, including NO-induced, Aβ (25–35)-induced, excitotoxic induced by glutamate or oxidative stress-induced by measuring the ‘cell viability. It will be interesting to investigate whether other compound exhibit neuro-protective activities (Cho et al., 2005). Subsequently, ECN (5) administration (5 mg kg−1/day) can significantly ameliorated movement impairments and dopaminergic neuronal damage induced by 6-hydroxydopamine in mice. As well as, ECN (5, 10 μM) increasing cell viability of up to 80.7 % and 87%, respectively. The result indicated that ECN can activate the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway both in vivo and vitro (Lee et al., 2018). However, a single dose was used throughout in vivo studies, which failed to reflect the dose-dependent response and enhance understanding of its function on diseases. Furthermore, Hwang et al. (2018) investigated that flower buds extracts of coltsfoot (300 mg kg−1, p.o.) had a neuro-protective effect (Hwang et al., 2018). However, further research should undergo to screen dominant compounds, which might be valuable for treating neurodegenerative illness.

6.3. Cytotoxicity and anti-cancer activity

All the existing studies focusing on the anti-cancer potential of coltsfoot can be characterized as preliminary (in vitro/vivo-based), using MTT assay. As highlighted in Table 5, different component from of coltsfoot were evaluated for the anti-cancer/anti-proliferation.

Notably, Lee et al. (2014) findings first indicate that MeOH fraction of leaves and stems from coltsfoot. It could be used as a novel TRAIL sensitizer, having been activity in TRAIL-resistant Huh7 cells (Table 5). Of particular interest, is the noteworthy anti-cancer activities demonstrated by sesquiterpenoids from the flower buds of coltsfoot for the eco-friendly synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles (Lee et al., 2019a).

In another study, TSL (13) isolated from coltsfoot was evaluated for the anti-cancer/anti-proliferation, with colon cancer cell (SW 480 and HCT116). The results revealed that TSL (13) may be held responsible for therapeutic new target and regard as potential scaffolds to treat angiogenesis dependent diseases (Li et al., 2019).

An in vitro study showed that TFPB1 (0–1000 μg ml−1), a homogeneous polysaccharide with a molecular weight of 37.8 kDa, dose-dependently induced apoptosis and inhibited proliferation (Table 5). Interestingly, TFPB1 (1 mg ml−1) could expansively arrest cell cycle in G2-M phase, hence it is worth noting that the underlying mechanism of different structural polysaccharides to further study on cell cycle (Qu et al., 2018).

6.4. Immunostimulating activities

Undoubtedly, chemotherapy causes damaging effects both in tumor and in healthy cells with high proliferative activity (Safonova et al., 2018b). It was interesting to see that polysaccharides from coltsfoot were employed to treat the side effects caused by chemotherapy. Safonova et al. (2019) found that polysaccharides sometimes potentiated the protective and/or stimulating effects of polychemotherapy in female C57Bl/6 mice with Lewis̕ s lung carcinoma and the processes of cell regeneration. In addition, the stimulating effect of polysaccharides was exhibited on the granulopoietic lineage cells, which was comparable with that of recombinant CSF neupogen (Safonova et al., 2018a). Subsequently, for the small intestinal epithelium polysaccharides also attenuated the toxic effect and stimulated reparative regeneration processes under conditions of polychemotherapy (Safonova et al., 2016). It is worth noting that polysaccharides do not stimulate the growth of tumor and metastasis (Safonova et al., 2019). The authors also proved that the genic protective properties of these polysaccharides in bone marrow cells and small intestinal epithelium of C57Bl/6 mice during polychemotherapy (Safonova et al., 2018b). Hence, coltsfoot, polysaccharides may be a promising agent for the generation of a new medicinal substance about polychemotherapy (Safonova et al., 2018b).

6.5. Anti-microbial and anti-viral effects

The majority of investigations focusing on the antimicrobial effects of coltsfoot have been conducted using the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), Extracts from different parts of coltsfoot have been evaluated against 47 bacteria, including both gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial strains (Table 6). As highlighted in Table 6, diverse levels of antimicrobial potency have been defined by several authors to identify medicinal plants with promising biological activity (Boucher et al., 2018; Hleba et al., 2014; Kokoska et al., 2002; Kuroda et al., 2016; Turker and Usta, 2008; Uysal et al., 2018).

Turker and Usta (2008) highlighted the key role of the type of solvent used for extracting the plant materials, and although Kokoska et al. (2002) studied MeOH extracts of coltsfoot aerial parts did not show antimicrobial activity against E. coli (Kokoska et al., 2002; Uysal et al., 2018), unlike the author's experiment, which showed inhibited this bacterial growth (Turker and Usta, 2008). However, the diameter of the inhibition zone which established about the tested extracts was measured instead of determination of minimum inhibitory activity.

Uysal et al. (2018) investigated the antimicrobial activity of the EtOAc, MeOH, water extracts of coltsfoot (Table 6). The authors suggested that the highest antimicrobial activity exhibited may be due to synergistic effect. However, the results were presented by the authors, which fail to mention the dose range used of the different extracts and the duration of cultivation of microorganisms with test ingredients (Uysal et al., 2018).

In terms of the antifungal potential of coltsfoot, several authors found that the extracts of this plant have exhibited moderate activity (Kokoska et al., 2002; Uysal et al., 2018).

Moreover, an in-vitro experiment has been reported revealing the anti-viral activity of coltsfoot (Table 6) (Chiang et al., 2017).

In conclusion, coltsfoot revealed broad-spectrum of activity against microorganism. The results confirmed the use of this plant in folk medicine for the treatment of various infections such as tuberculosis.

6.6. Anti-diabetic and anti-obesity

Several studies have evaluated the anti-diabetic activity of coltsfoot, mainly with in vitro models.

Park et al. (2008) investigated TSL(13) can be effectively inhibit acyl CoA prepared from in rat liver (IC50 = 18.8 μM L−1) and HepG2 cells (IC50 = 49.1 μM L−1) microsomal protein in a dose-dependent manner respectively, using a positive control of kurarinone with IC50 values of 10.9 and 28.8 μM in the assay (Park et al., 2008). Additionally, Gao et al. (2008) suggested that caffeoylquinic acid significantly inhibited a-Glucosidase effect as well, the remarkable works have been defined due to its structure-activity relationship that the number of caffeoyl groups attached to a quinic acid core. The research was a conclusion that coltsfoot can be physiologically useful for overwhelming postprandial hyperglycemia by ingesting it in the diet (Gao et al., 2008).

Recently, Uysal et al. (2018) also demonstrated the anti-diabetic activities of coltsfoot, which were evaluated as acarbose equivalents (mmol ACAE/g extract). Indeed, the EtOAc extract possessed potential effective against α-amylase (0.75 mmol ACAE/g extract) and the MeOH extract against α-glucosidase (22.11 mmol ACAE/g extract). Subsequently, molecular dynamic calculation evaluated the complexes of bioactive chlorogenic (83) and rosmarinic (95) acids with α-glucosidase compare to acarbose. The study concluded that the relevant presence of both chlorogenic (83) and rosmarinic (95) acids has displayed notable anti-diabetic property (Uysal et al., 2018). However, these studies have not determined the enzyme specificity and biological efficacy of coltsfoot extract in vivo model.

6.7. Anti-oxidant activity

The antioxidant potential of coltsfoot was evaluated using various approaches and assays in vitro. As shown in Table 7 phenolic acid (Song et al., 2010), quercetin-glycosides (Kim et al., 2006) and polysaccharides (Qin, K. et al., 2014) were major antioxidant compounds in this plant. However, among of the extracts demonstrated anti-oxidant and free radical scavenging activities based on different biochemical assays only.

Dragicevic et al. (2019) firstly, investigated the anti-oxidative properties of coltsfoot leaf water extracts in vitro, in human cell lines. Treatment of human bronchial epithelial cell lines with preparing plant extracts exhibited a significant anti-oxidative effect when oxidative stress was induced by hydrogen peroxide (Dragicevic et al., 2019). However, their potential under in vivo, conditions and underlying mechanisms need to be investigated for these effects to be considered clinically relevant.

6.8. Cardiovascular

Li and Wang (1988) evaluated the cardiovascular effects of TSL (13). The authors indicated that the treatment of anesthetized rats, cats and dogs injected with TSL 0.4–4, 0.02–0.5, 0.02–0.3 mg kg−1, respectively. Four animals produced an instant and dose dependent pressor effect within six minimums, similar to that of dopamine (0.01–0.03 mg kg−1). Unfortunately, tachyphylaxis was not observed. It can be seen that dose-related decrease in the heart rate of anesthetized dogs, as well as the acute injection LD50 in mice of TSL (13) was 28.9 mg kg−1 Other studies suggested that the mechanism of cardiovascular effect of TSL (13) was peripheral, which was totally different from that of norepinephrine (Li and Wang, 1988).

6.9. Cytoprotective

A paper highlighted the critical role of the cytoprotective activities in the EtOAc extracts of coltsfoot. In this research, EtOAc extracts were studied, with mouse fibroblast NIH3T3 cells and human keratinocyte HaCaT cells having been used. In this in-vitro study, all compounds (0.1, 1, 10,100 μM) showed impressive protection against glucose oxidase-induced oxidative stress in a dose dependent manner were significantly stronger than that of the ẟ-Tocopherol (a positive control). even, incubation with 100, 102 and 88 μM promoted the proliferation of NIH3T3 cells (Kang et al., 2016).

7. Pharmacokinetics

Until now, few pharmacokinetic investigations have been done on coltsfoot. The concentration-time course of nodakenin was best fitted to a one-compartment model after 200 mg kg−1 TSL (13) at a single dose by intragastrical administration, which the main the plasma concentration–time curve pharmacokinetic parameters T1/2 of 6.80 min, Tlag of 22.55 min, Tmax of 28.21 min, Cmax 3.91 μg/m L, K10 of 0.10 min−1, K01 of 0.28 min−1, AUC of 68.37 μg min/L. while a injecting 5 mg kg−1 nodakenin at a single dose intravenously, there was a biphasic phenomenon with a rapid distribution followed by a slower elimination phase, which were found conformed to best a two-compartment open model (Liu et al., 2008). Furthermore, in all, 35, 37, 18 and 9 metabolites of TSL (13), methl butyric acid tussilagin ester, senkirkine (126) and senecionine (127) were tentatively identified, including 16 in plasma, 43 bile, 29 urine and 41 metabolites in feces. The metabolic pathway of these components was also elucidated, which common reactions were demethylation, oxidation and reduction (Cheng et al., 2018).

Recently, Cheng et al. (2018) have been proposed UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS method for the simultaneous screening and identification of two kinds of main active ingredients and hepatotoxic pyrrolizidine in rat after lavage of coltsfoot extracts. In all, 35, 37, 18 and 9 metabolites of TSL (13), meth butyric acid tussilagin ester, senkirkine (126) and senecionine (127) were tentatively identified, including 16 in plasma, 43 bile, 29 urine and 41 metabolites in feces. The metabolic pathway of these components was also elucidated, which common reactions were demethylation, oxidation and reduction. Furthermore, the isomers of metabolites were also estimated (Cheng et al., 2018).

Moreover, a UHPLC/HRMS method was carried out to compare the biotransformation of TSL (13) both in rat's and human's liver microsomes in vitro, confirming the CYP isoforms involved in the metabolism by recombinant human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Totally, nine metabolites were identified. As well as the authors indicated that the possible metabolic pathway of TSL (13) was hydrolysis of ester bonds and hydroxylation that the CYPs, CYP3A4 played a key role. In addition, the species-related difference of TSL (13) between RLMs and HLMs in the metabolism was described (Zhang et al., 2015).

8. Quality control (QC)

According to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2015), TSL (13) has been a QC marker of the coltsfoot, the quantity of which must be more than 0.07% (w/w). Indeed, it is unreliable and difficult to quantify the TSL using UV detection. Hence, absolutely quantified of TSL (13) by the UHPLC-MRMHR is desired (Song et al., 2019).