Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation can be a potential cure for hematological malignancies and some nonhematologic diseases. Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) collected from peripheral blood after mobilization are the primary source to provide HSC transplantation. In most of the cases, mobilization by the cytokine granulocyte colony-stimulating factor with chemotherapy, and in some settings, with the CXC chemokine receptor type 4 antagonist plerixafor, can achieve high yield of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs). However, adequate mobilization is not always successful in a significant portion of donors. Research is going on to find new agents or strategies to increase HSC mobilization. Here, we briefly review the history of HSC transplantation, current mobilization regimens, some of the novel agents that are under investigation for clinical practice, and our recent findings from animal studies regarding Notch and ligand interaction as potential targets for HSPC mobilization.

Keywords: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, mobilization, G-CSF, plerixafor, Notch2 blockade

Introduction

E. Donnall Thomas was a pioneer in applying experience from animal bone marrow (BM) transplantation on leukemic patients. In 1959, he and his colleagues reported 3-month remission in a patient with total body irradiation followed by infusion of identical twin’s marrow1. Though Thomas’ finding was exciting, it was limited to isologous marrow infusion. In 1960, however, allogeneic transplantation was accomplished after human leukocyte antigen (HLA), the major histocompatibility complex, was discovered. An immunodeficient patient received marrow transplantation from an HLA-matched sibling without rejecting the allograft2. A decade later, after Thomas’ success, he and his colleagues cured some patients with end-stage acute leukemia by using a combination of chemotherapy, that is, cyclophosphamide (CY), with total body irradiation, followed by BM infusion from HLA-identical siblings3. Furthermore, the ability of donor lymphocyte to eliminate the tumor cells that have survived after ablative therapy was found to contribute to the reduction in the incidence of leukemic relapse after allograft transplantation. However, these lymphocytes may also contribute to a phenomenon called graft-versus-host disease4.

At the same time, other animal experiments discovered that nonleukemic blood cells egress from BM to peripheral blood system giving rise to mature blood cells and compensating damaged BM to maintain hematopoietic homeostasis5,6. These hematopoietic cells act as substitute sources to BM progenitor cells. However, Lewis and colleagues in 1968 suggested that due to the low frequency of the repopulating peripheral blood leukocytes (estimated to be 1/100th that of marrow), grafting would not be accomplished using these cells for transplantation7. Fortuitously, around the same time, a continuous flow centrifuge (apheresis) machine was developed to improve harvesting enough peripheral repopulating units for transplantation in patients with chronic myelocytic leukemia8,9. Nevertheless, several subsequent attempts to transfuse peripheral white blood cells among identical twins did not give a plausible engraftment result8,10. Putatively, the reason for the failure was due to the insufficient number of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) present in the peripheral blood compared to those in the BM.

Cryopreservation technique was developed in the 1970s and was found effective in preserving the hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from the peripheral blood11. Years later, using cryopreserved cells obtained from multiple rounds of apheresis before the transplantation resulted in successful hematopoietic engraftment12–16. Despite many successes of cryopreserved HSPC infusion, harvesting a sufficient number of peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) for multiple rounds over a long time of collection was not feasible. However, the subsequent introduction of the course of CY and adriamycin chemotherapy resulted in ∼20-fold increase of PBSC yield, suggesting that chemotherapy could enhance PBSCs mobilization17,18.

In this review, we will first address the current HSPC-mobilizing agents, including chemotherapy, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and plerixafor, and other reagents that are still being investigated at various stages but not yet applied clinically. We will then discuss our recent animal research findings demonstrating the enhanced potential of HSPC egress and mobilization by blocking Notch or Notch ligands.

G-CSF and Chemotherapy

The clinically approved growth factor G-CSF has been widely used to mobilize both HSC and hematopoietic progenitor cell (HPC) for transplantation. G-CSF is a cytokine that promotes granulocyte proliferation and differentiation and enhances mobilization through direct or indirect protease activation. After G-CSF administration, neutrophil releases neutrophil elastase, cathepsin, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), and the cell surface protease dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4, cluster of differentiation (CD) 26) cleaves the adhesion molecules on HSPCs. These molecules, including stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1)/CXC chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4), stem cell factor (SCF; also called c-kit), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1)/ very late antigen-4 (VLA-4), are responsible for HSCs retention in the BM19–23. In addition, G-CSF indirectly inhibits osteoblast (OB) activity and reduces SDF-1 (also called CXCL12) expression that enhances HSPC mobilization24. Administration of G-CSF benefits both autologous and allogeneic mobilization, increases engraftment rate, and reduces hospitalization length and cost25–28. The minimum target dose (≥2 × 106 CD34+ cells per kg weight) could be successfully achieved by 5–10 μg/kg of G-CSF per day for 5–7 days with one or more days of apheresis. However, a study led by Mayo Clinic demonstrated less than optimum mobilization in two groups of patients: non-Hodgkin lymphoma (71%) and multiple myeloma (30%)29. In autologous stem cell transplantation, chemotherapy is commonly used along with G-CSF to reduce the tumor burden, to enhance mobilization as well as to decrease the apheresis sessions and transfusion volumes. In myeloma patients, an intermediate dose of CY effectively mobilized HSPC30. On the other hand, in lymphoma patients, combination chemotherapies include G-CSF with CY, etoposide, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin (DHAP), and other chemotherapy regimens31–35 are often required for effective mobilization. Therefore, new agents with improved ability to increase stem cell yield and to reduce the number of apheresis sessions are required, particularly for those heavily pretreated patients.

Plerixafor

Plerixafor, or Mozobil (AMD3100), is the antagonist of CXCR4. AMD3100 prevents CXCR4 on HSCs from interacting with SDF-1 on BM stroma36–38. BM OB, mesenchymal stem cells, and CXCL12-abundant reticular cells secrete SDF-1 to maintain HSC retention39, and disrupting this interaction between CXCR4 and SDF-1 leads to the mobilization of HSPCs to the periphery. AMD3100 administration not only blocks CXCR4, but also induces activation of MMP-9 and serine protease urokinase-type plasminogen activator40,41. Currently, plerixafor is clinically approved to use alone or in combination with G-CSF to mobilize HSPC in heavily pretreated lymphoma and myeloma patients42–47. Although plerixafor is successful in increasing optimal CD34+ yield, decreasing mobilization failure, and reducing the number of apheresis sessions, its universal use is limited by its expensive cost48–53.

Other Mobilizing Agents

Studies in mice have shown that two main axes are targeted directly or indirectly by most mobilizing agents, CXCR4 and the integrin VLA-4 signaling, or both54. Integrins are a family of proteins implicated in HSPC mobilization. Integrin adhesion receptors such as VLA-4 found on HSCs tether with VCAM-1 within the BM stroma55–57. Indeed administration of anti-VLA-4 led to the mobilization of HSPC to the peripheral blood58,59.

While some agents, like G-CSF, target both pathways directly or indirectly, some only affect one adhesion molecule. An example of an approach that affects both CXCR4 and VLA-4 signaling is parathyroid hormone, which increases the secretion of G-CSF. In turn, this results in an increase in peripheral circulating HSC by 1.5- to 9.8-folds in mice60, and in a phase I clinical trial study, it induced adequate mobilization in 40%–47% of patients who have failed prior mobilization for autologous stem cell transplantation61. Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), an agent mainly targeting the CXCR4 signaling, is a bioactive lipid mediator mainly found in red blood cells and acts as a ligand to G-protein-coupled S1P receptors. A high concentration of plasma S1P creates a gradient and egresses HSPC62–65. Furthermore, during mobilization, HSPC egress is further mediated by the S1P gradient increase in peripheral blood as a result of erythrocyte lysis by the complement cascade and the membrane attack complex activation66,67. An alternative adhesion molecule target exists for proteasome inhibitors, such as bortezomib, which affects angiopoietin levels. Bortezomib successfully stimulated HSC mobilization in 85% of multiple myeloma patients receiving a bortezomib-based induction regimen68. Other agents or approaches that are currently undergoing investigation include cytokines, chemokines, chemokine receptor antagonists, bacterial toxins, proteases, inhibitors of adhesive cell interactions, ephrinA3 receptor antagonists, polymeric sugar molecules, prostaglandin inhibitors, blockade of heparan sulfate, Nlrp3 inflammasome activation, and stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, among others54. Table 1 summarizes various agents that have been used in mice and their target adhesion molecules.

Table 1.

Mobilizing Agents (Not Including G-CSF and Plerixafor) and Their Target Adhesion Molecules.

| General class | Agent | Target adhesion molecule (direct or indirect) |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokines and chemokine | Stem cell factor69–71 | CXCR4 and VLA-4 |

| FLT3 ligand72,73 | CXCR4 and VLA-4 | |

| Thrombopoietin74 | Mpl | |

| Angiopoietin75,76 | Angiopoietin | |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor76,77 | VEGFR2 | |

| IL-178, IL-379, IL-680, IL-781, IL-1282, IL-1783, and IL-3384 | Various | |

| CXCL12 and analogs85 | CXCR4 | |

| Gro-α86 | CXCR2 | |

| Gro-β86,87 | CXCR2 | |

| Gro-γ86 | CXCR2 | |

| IL-888,89 | Unknown | |

| Chemokine receptor antagonists | Inhibitors of the small Rho GTPase Rac1 inhibitors90,91 | CXCR4 |

| Bioactive lipids | Sphingosine-1 phosphate92 | CXCR4 |

| Ceramide-1 phosphate92 | Unknown | |

| Bacterial toxins93 | Lipopolysaccharide94 | CXCR4 |

| Pertussis toxin95 | CXCR4 | |

| Proteases | Trypsin96 | CXCR4 |

| Matrix metalloprotease 997 | CXCR4 | |

| CD2698 | CXCL12 | |

| Cathepsin G99 | CXCR4 | |

| Neutrophil elastase99 | CXCR4 | |

| Inhibitors of adhesive cell interactions59 | VLA-4100,101 | VLA-4 |

| VLA-4/VLA-9 inhibitors102 | VLA-4 | |

| VCAM-1103 | VLA-4 | |

| CD44 blockers104 | CD44v10 | |

| Polymeric sugar molecules | Dextran105 | Likely CXCR4 |

| Fucoidan106 | CXCL12 (SDF-1) | |

| Betafectin PGG-glucan107 | Unknown | |

| Glycosaminoglycan mimetics108 | CXCL12 (SDF-1) | |

| Others | Defibrotide109 | Endothelial adhesion molecules |

| Prostaglandin inhibitors110 | Osteopontin | |

| Proteasome inhibitors (Bortezomib)111 | CXCL12, angiopoietin, etc. | |

| Parathyroid hormone60 | CXCR4 and VLA-4 | |

| Blockade of heparan sulfate112 | VLA-4 | |

| Stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α113 | CXCR4 | |

| Ephrin A3 receptor antagonists114 | VLA-4 | |

| Activation of Nlrp3 inflammasome115 | Nlrp3 | |

| Notch2 blockade116 | Notch2 and CXCR4 |

CD: cluster of differentiation; CXCR: CXC chemokine receptor type; CXCL12: C-X-C motif chemokine 12; FLT3: fms like tyrosine kinase 3; G-CSF: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; IL: interleukin; PGG-glucan: Poly-[1-6]--D-glucopyranosyl-[1-3]--D-glucopyranose glucan; SDF-1: stromal cell-derived factor; VCAM-1: vascular cell adhesion molecule; VEGFR2: vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2; VLA: very late antigen.

Systemic Factors

Several factors affect HPSC mobilization on the systemic level. These include cortisol level, the time of day, stress, exercise, trauma, infection and inflammation, elements in coagulation and complement cascades, and signals from the sympathetic and central nervous systems54. These factors may contribute to the overall stem cell collection during apheresis procedures.

Notch2 and Notch Ligand Blockade

Notch signaling plays a critical role in multiple pathways that control cell fate determination, such as embryogenesis, neurogenesis117–120, angiogenesis121, cardiogenesis122, and hematopoiesis123. In hematopoiesis, this signaling not only regulates lymphopoiesis but also regulates myelopoiesis124,125. Notch pathway alterations play critical roles in several cancer types and particularly in hematologic malignancies. Therefore, it is a desirable target in these neoplasms. However, inhibiting a downstream enzyme, the gamma-secretase, in this pathway, has not been successful due to side effects from global inhibition of wild-type Notch proteins. On the other hand, targeting specific Notch proteins, for example, Notch1 or Notch2, may still be promising126. An essential feature of Notch is its adhesive nature, which was first described by cell aggregation assays in Drosophila 127,128. However, the precise role and the biological significance of Notch receptors and ligands as adhesion and signaling molecules in HSC biology, particularly in the context of HSC cell therapy, have not been well defined. Here we will report our recent findings suggesting that Notch2 and its interaction with Notch ligand may serve as potential effective HSPC-mobilizing targets.

In mammals, the canonical Notch signaling pathway is initiated by binding interactions between the extracellular domain of a Notch family member (Notch1–4) on a receiving cell and a Notch ligand of the Jagged (Jagged 1 and 2) or Delta-like (DLL1, 3, and 4) families on a sending cell129. It is generally accepted that ligand binding initiates ligand endocytosis and successive proteolytic cleavages, which culminate in the release of the intracellular domain of Notch and the formation of a large transcriptional activation complex leading to the activation of downstream targets of Notch signaling130,131. Despite in vitro evidence that activation of Notch stimulates HSC self-renewal132–135, the in vivo function of Notch in HSC is still debatable. Conditional deletion of Notch receptors, ligands, or Notch canonical targets does not appear to affect HSC steady-state homeostasis136,137. In contrast, Notch2 was found responsible for the rate of generation of repopulating stem cells during stress hematopoiesis and the early phase of hematopoietic recovery138. Also, Jagged1 expressed by BM endothelial cells regulates homeostasis and regenerative hematopoiesis, while DLL4 expressed by osteocalcin-expressing bone cells is responsible for generating early thymus progenitors139,140.

We and others found that Notch2 is the primary Notch receptor expressed on HSCs and nonlymphoid committed progenitors. In comparison, Notch1 expression level is low on HSC cells but high on lymphoid progenitors141,142. Notch transactivation is the result of the engagement of Notch receptors with Notch ligands. This process is dependent on posttranslational modification of Notch receptors with O-glucose and O-fucose, added to serine in the consensus C1-X-S-X-(P/A)-C2 or to serine or threonine residue in the consensus sequence C2-X-X-X-X-(S/T)-C3 143–145, by protein O-glucosyltransferase 1 (Poglut) or protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 (Pofut1), respectively, on the epidermal growth factor (EGF) modules of Notch extracellular domain146–149. O-Fucose, but not O-glucose, enhances Notch affinity for Jagged or Delta-like ligands and regulates Notch signaling transactivation147,150–152. This notion is supported by crystal structural determinations showing that O-fucose attached to the Thr residue of Notch1 EGF-like repeat acts as a surrogate amino acid to make functional contact with a specific domain on DLL4 (contact Notch1 EGF12) and Jagged1 (contact Notch1 EGF8 and 12), and thus directly affects Notch ligand binding153,154. Elongation of O-fucose to a disaccharide (GlcNAc-fucose) on EGF12 by any of three Fringe enzymes (N-acetyl-glucosaminyltransferase)-Lunic fringe (Lfng), Manic fringe (Mfng), or Radical fringe (Rfng) further increases Notch1 binding affinity to Jagged1 and DLL1 and affects Notch activity in slightly different ways145,155–158.

To understand the role of Notch O-fucose glycan modification in its adhesive interaction with Notch ligand in the marrow HSC compartment, we studied mice with Pofut1 deletion, and thus O-fucose deficiency125,141,159. These mice developed increased HSC cycling and increased HSPC egress from the marrow manifested as neutrophilia along with an increase in circulating myeloid progenitors. The altered homeostasis of O-fucose-deficient HSC is accompanied by the more distal locations of Lin–c-kit+Sca-1+ (LSK) cells relative to the endosteum and the OBs when compared to control HSCs159. The increased cell-autonomous HSC cycling and egress are primarily accounted for by a loss of binding of O-fucose-deficient HSC to Notch ligands141,160. The loss of binding results in a decreased adhesion of Pofut1-deficient HSCs to marrow stromal cells. In the in vitro cell adhesion assay, wild type (WT) long-term HSCs (LT-HSC; CD48–CD150+LSK), but not O-fucose-deficient LT-HSCs from Pofut1-null mice, showed 15%–25% increased adhesion to a stromal cell line from mouse bone marrow (OP9) cells expressing Notch ligand (Jagged1, DLL1, or DLL4) relative to parental OP9 cells160. The recombinant ligand entirely blocked the Notch ligand-mediated adhesion. Further, co-culture with OP9-DLL1, OP9-DLL4, or primary calvarium OBs increased the quiescent cell fraction of WT LSKs in G0 phase (from basal level 17% to 37%, 48%, and 67%, respectively), whereas Pofut1-null LSKs remained less quiescent on OP9-DLL1/DLL4 or primary calvarium OBs.

To examine the specific contribution of different Notch ligands and Notch receptors that support HSC quiescence and niche retention, we applied neutralizing antibodies targeting Notch ligand Jagged1 or DLL4. These antibodies block specific interaction of each ligand to Notch receptors161,162. Both Jagged1 and DLL4 are expressed in BM endothelial cells and OBs/osteolineage cells133,140,163–165. In vivo, we found that circulating LSK and LK cells in the periphery of mice receiving anti-Jagged1 or anti-DLL4 increased 2.5- to 3.3-fold, respectively, compared to those receiving isotype control antibodies. White blood cells increased modestly, while platelet numbers did not change significantly in mice receiving anti-Jagged1 or anti-DLL4. There was an increase in circulating granulocytes and a decrease in T lymphocytes in mice receiving anti-DLL4 but not in mice receiving anti-Jagged1160. HSPC frequencies did not change, except that common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) decreased in anti-DLL4-treated mice, consistent with the role of DLL4 in promoting CLP development in other reports140. We found that there was an increase in marrow HSPC proliferation following DLL4 but not after Jagged1 blockade. Further, mice receiving Jagged1- or DLL4-antibody followed by G-CSF (4 doses) and plerixafor treatment showed a further ∼50% increase in LSK mobilization relative to control-treated mice160.

More recently, we examined the effects of Notch receptor blockade. Unlike ligand neutralizing antibodies, Notch receptor-specific blocking antibodies do not interfere with receptor–ligand interaction, but instead block cleavage of Notch receptors and thus downstream signaling activation161. We found that in mice receiving Notch2-blocking antibodies, but not Notch1-blocking antibodies, spleen-residing LSKs and LKs increased three- to four-fold. When mice were given G-CSF and plerixafor following four doses of anti-Notch2 treatment, a 2.5-fold increase of white blood cells, a 3- and 3.3-fold increase of LSKs and LKs were seen in the periphery, and a 3.6- and 2-fold increase of spleen-residing LSKs and LKs were found in mice receiving anti-Notch2 compared to control-treated mice116. However, Notch2 blockade, combined with G-CSF or plerixafor, did not affect marrow HSPC homeostasis. We confirmed that increased HSPC egress following Notch2 blockade is a result of Notch2 signaling loss in the hematopoietic system, since Notch2 deletion in hematopoietic tissues caused increased cell-autonomous egress of HSPC to the PB and the spleen by reconstituted Notch2-deficient BM cells from Vav-Cre/Notch2F/F mice in wild-type recipients. However, the HSPC homeostasis was not much affected in the marrow of Notch2-deficient mice.

Similar to the effect of anti-DLL4, the quiescent G0 HSCs were decreased in mice receiving Notch2 antibodies or in the marrow of Notch2-deficient mice116. We show that transient Notch2 blockade or Notch2 loss in mice leads to decreased HSPC CXCR4 expression but increased cell cycling with CXCR4 transcription being directly regulated by the Notch transcriptional protein RBPJ. Surprisingly, we found that Notch2 blockade enhances HSPC homing and hematopoietic recovery. We observed that a 1.9-fold more of Notch2-blocked progenitors homed to the BM compared to their corresponding controls. We studied the hematopoietic reconstitution at various time points after the transplantation of cells from mice that received either control antibody, Notch1 or Notch2 blocking antibodies. Peripheral blood analysis revealed a better recovery of platelets at 4 and 8 weeks and a higher hemoglobin level until 10 weeks in recipient mice receiving Notch2-blocked cells than in mice receiving control-treated cells or Notch1-blocked cells. Analysis of BM 3 months after transplantation showed that the megakaryoerythroid progenitors and the common myeloid progenitors, derived from Notch2- but not Notch1-blocked donors, increased by ∼92% and 75%. At the same time, alteration to the HSC homeostasis did not occur.

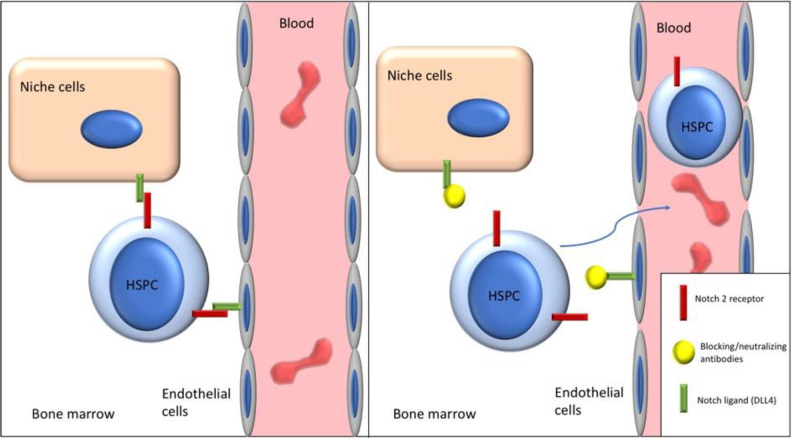

In summary, either blocking Notch ligand adhesion through neutralizing Jagged1 or DLL4 or blocking Notch2 signaling induces HSPC egress and mobilization without significantly affecting HSC homeostasis (Fig. 1). In addition, transient Notch2 blockade results in higher engraftment and better myeloid reconstitution. The underlying mechanism is being investigated.

Figure 1.

Blocking of Notch2-ligand adhesion through neutralizing and blocking antibodies induces HSPC egress and mobilization. DLL4: Delta-like 4; HSPC: hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell.

Conclusion

Hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) is a potentially curative therapy for blood and nonhematologic disorders. A successful outcome is dependent on the infusion of an adequate number of functionally active mobilized HSPCs. Until recently, G-CSF, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy, failed to mobilize an optimal CD34+ cell dose (5 × 106/kg) in up to 40% of patients166. Plerixafor, in combination with G-CSF, increased total CD34+ cells mobilized and often is used for HPC mobilization in myeloma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients167. Unfortunately, this approach does not always lead to adequate HSPC collection in patients with prior extensive cytotoxic therapy. In some instances, multiple HCT procedures may require higher numbers of HSPCs168–170. Newer mobilizing regimens, either alone or in combination with G-CSF and plerixafor, have shown improved collection efficacy in preclinical models and could facilitate the collection of sufficient cells for multiple transplants and significantly decrease procedure-related risks, such as thrombocytopenia and infection associated with large volume or multiple collections171–173.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: MA, LZ; literature search and data analysis: MA, HT, LZ; writing—original draft: MA, LZ; writing—review and editing: HT, LZ.

Ethical Approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting review articles.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent: There are no human subjects in this article and informed consent is not applicable.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported in part by research funding from NCI CA222064 and NIH HL103827 (to LZ), and by the Department of Pathology Case Western Reserve University faculty startup fund to LZ.

ORCID iD: Lan Zhou  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1291-534X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1291-534X

References

- 1. Thomas ED, Lochte HL, Jr, Cannon JH, Sahler OD, Ferrebee JW. Supralethal whole body irradiation and isologous marrow transplantation in man. J Clin Invest. 1959;38(10 Pt 1-2):1709–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gatti RA, Meuwissen HJ, Allen HD, Hong R, Good RA. Immunological reconstitution of sex-linked lymphopenic immunological deficiency. Lancet. 1968;2(7583):1366–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thomas ED, Buckner CD, Banaji M, Clift RA, Fefer A, Flournoy N, Goodell BW, Hickman RO, Lerner KG, Neiman PE, Sale GE, et al. One hundred patients with acute leukemia treated by chemotherapy, total body irradiation, and allogeneic marrow transplantation. Blood. 1977;49(4):511–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weiden PL, Flournoy N, Thomas ED, Prentice R, Fefer A, Buckner CD, Storb R. Antileukemic effect of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of allogeneic-marrow grafts. N Engl J Med. 1979;300(19):1068–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bond VP, Fliedner TM, Cronkite EP, Rubini JR, Brecher G, Schork PK. Proliferative potentials of bone marrow and blood cells studied by in vitro uptake of H3-thymidine. Acta Haematol. 1959;21(1):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bond VP, Cronkite EP, Fliedner TM, Schork P. Deoxyribonucleic acid synthesizing cells in peripheral blood of normal human beings. Science. 1958;128(3317):202–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lewis JP, Passovoy M, Freeman M, Trobaugh FE., Jr The repopulating potential and differentiation capacity of hematopoietic stem cells from the blood and bone marrow of normal mice. J Cell Physiol. 1968;71(2):121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hershko C, Gale RP, Ho WG, Cline MJ. Cure of aplastic anaemia in paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria by marrow transfusion from identical twin: failure of peripheral-leucocyte transfusion to correct marrow aplasia. Lancet. 1979;1(8123):945–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buckner D, Graw RG, Jr, Eisel RJ, Henderson ES, Perry S. Leukapheresis by continuous flow centrifugation (CFC) in patients with chronic myelocytic leukemia (CML). Blood. 1969;33(2):353–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abrams RA, Glaubiger D, Appelbaum FR, Deisseroth AB. Result of attempted hematopoietic reconstitution using isologous, peripheral blood mononuclear cells: a case report. Blood. 1980;56(3):516–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fliedner TM, Korbling M, Calvo W, Bruch C, Herbst E. Cryopreservation of blood mononuclear leukocytes and stem cells suspended in a large fluid volume. a preclinical model for a blood stem cell bank. Blut. 1977;35(3):195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bell AJ, Figes A, Oscier DG, Hamblin TJ. Peripheral blood stem cell autografts in the treatment of lymphoid malignancies: initial experience in three patients. Br J Haematol. 1987;66(1):63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. To LB, Dyson PG, Branford AL, Russell JA, Haylock DN, Ho JQ, Kimber RJ, Juttner CA. Peripheral blood stem cells collected in very early remission produce rapid and sustained autologous haemopoietic reconstitution in acute non-lymphoblastic leukaemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1987;2(1):103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reiffers J, Bernard P, David B, Vezon G, Sarrat A, Marit G, Moulinier J, Broustet A. Successful autologous transplantation with peripheral blood hemopoietic cells in a patient with acute leukemia. Exp Hematol. 1986;14(4):312–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kessinger A, Armitage JO, Landmark JD, Weisenburger DD. Reconstitution of human hematopoietic function with autologous cryopreserved circulating stem cells. Exp Hematol. 1986;14(3):192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Korbling M, Dorken B, Ho AD, Pezzutto A, Hunstein W, Fliedner TM. Autologous transplantation of blood-derived hemopoietic stem cells after myeloablative therapy in a patient with Burkitt’s lymphoma. Blood. 1986;67(2):529–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greenberg P, Bax I, Mara B, Schrier S. Alterations of granulopoiesis following chemotherapy. Blood. 1974;44(3):375–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bull JM, DeVita VT, Carbone PP. In vitro granulocyte production in patients with Hodgkin’s disease and lymphocytic, histiocytic, and mixed lymphomas. Blood. 1975;45(6):833–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Levesque JP, Takamatsu Y, Nilsson SK, Haylock DN, Simmons PJ. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD106) is cleaved by neutrophil proteases in the bone marrow following hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 2001;98(5):1289–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levesque JP, Hendy J, Takamatsu Y, Simmons PJ, Bendall LJ. Disruption of the CXCR4/CXCL12 chemotactic interaction during hematopoietic stem cell mobilization induced by GCSF or cyclophosphamide. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(2):187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Petit I, Szyper-Kravitz M, Nagler A, Lahav M, Peled A, Habler L, Ponomaryov T, Taichman RS, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Fujii N, Sandbank J, et al. G-CSF induces stem cell mobilization by decreasing bone marrow SDF-1 and up-regulating CXCR4. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(7):687–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Levesque JP, Hendy J, Takamatsu Y, Williams B, Winkler IG, Simmons PJ. Mobilization by either cyclophosphamide or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor transforms the bone marrow into a highly proteolytic environment. Exp Hematol. 2002;30(5):440–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levesque JP, Hendy J, Winkler IG, Takamatsu Y, Simmons PJ. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor induces the release in the bone marrow of proteases that cleave c-KIT receptor (CD117) from the surface of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Exp Hematol. 2003;31(2):109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Semerad CL, Christopher MJ, Liu F, Short B, Simmons PJ, Winkler I, Levesque JP, Chappel J, Ross FP, Link DC. G-CSF potently inhibits osteoblast activity and CXCL12 mRNA expression in the bone marrow. Blood. 2005;106(9):3020–3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tamura M, Hattori K, Nomura H, Oheda M, Kubota N, Imazeki I, Ono M, Ueyama Y, Nagata S, Shirafuji N, et al. Induction of neutrophilic granulocytosis in mice by administration of purified human native granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;142(2):454–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kennedy MJ, Davis J, Passos-Coelho J, Noga SJ, Huelskamp AM, Ohly K, Davidson NE. Administration of human recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (filgrastim) accelerates granulocyte recovery following high-dose chemotherapy and autologous marrow transplantation with 4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide-purged marrow in women with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53(22):5424–5428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McQuaker IG, Hunter AE, Pacey S, Haynes AP, Iqbal A, Russell NH. Low-dose filgrastim significantly enhances neutrophil recovery following autologous peripheral-blood stem-cell transplantation in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders: evidence for clinical and economic benefit. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(2):451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jansen J, Thompson EM, Hanks S, Greenspan AR, Thompson JM, Dugan MJ, Akard LP. Hematopoietic growth factor after autologous peripheral blood transplantation: comparison of G-CSF and GM-CSF. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23(12):1251–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gertz MA, Wolf RC, Micallef IN, Gastineau DA. Clinical impact and resource utilization after stem cell mobilization failure in patients with multiple myeloma and lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45(9):1396–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hiwase DK, Bollard G, Hiwase S, Bailey M, Muirhead J, Schwarer AP. Intermediate-dose CY and G-CSF more efficiently mobilize adequate numbers of PBSC for tandem autologous PBSC transplantation compared with low-dose CY in patients with multiple myeloma. Cytotherapy. 2007;9(6):539–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pavone V, Gaudio F, Guarini A, Perrone T, Zonno A, Curci P, Liso V. Mobilization of peripheral blood stem cells with high-dose cyclophosphamide or the DHAP regimen plus G-CSF in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29(4):285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee JL, Kim S, Kim SW, Kim EK, Kim SB, Kang YK, Lee J, Kim MW, Park CJ, Chi HS, Huh J, et al. ESHAP plus G-CSF as an effective peripheral blood progenitor cell mobilization regimen in pretreated non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: comparison with high-dose cyclophosphamide plus G-CSF. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35(5):449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Watts MJ, Ings SJ, Leverett D, MacMillan A, Devereux S, Goldstone AH, Linch DC. ESHAP and G-CSF is a superior blood stem cell mobilizing regimen compared to cyclophosphamide 1.5 g m(-2) and G-CSF for pre-treated lymphoma patients: a matched pairs analysis of 78 patients. Br J Cancer. 2000;82(2):278–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mollee P, Pereira D, Nagy T, Song K, Saragosa R, Keating A, Crump M. Cyclophosphamide, etoposide and G-CSF to mobilize peripheral blood stem cells for autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;30(5):273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pocali B, De Simone M, Annunziata M, Palmieri S, D’Amico MR, Copia C, Viola A, Mele G, Schiavone EM, Ferrara F. Ifosfamide, epirubicin and etoposide (IEV) regimen as salvage and mobilization therapy for refractory or early relapsing patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45(8):1605–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. De Clercq E. Antiviral drug discovery: ten more compounds, and ten more stories (part B). Med Res Rev. 2009;29(4):571–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nie Y, Han YC, Zou YR. CXCR4 is required for the quiescence of primitive hematopoietic cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205(4):777–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tzeng YS, Li H, Kang YL, Chen WC, Cheng WC, Lai DM. Loss of Cxcl12/Sdf-1 in adult mice decreases the quiescent state of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and alters the pattern of hematopoietic regeneration after myelosuppression. Blood. 2011;117(2):429–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nombela-Arrieta C, Ritz J, Silberstein LE. The elusive nature and function of mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(2):126–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dar A, Schajnovitz A, Lapid K, Kalinkovich A, Itkin T, Ludin A, Kao WM, Battista M, Tesio M, Kollet O, Cohen NN, et al. Rapid mobilization of hematopoietic progenitors by AMD3100 and catecholamines is mediated by CXCR4-dependent SDF-1 release from bone marrow stromal cells. Leukemia. 2011;25(8):1286–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Janowska-Wieczorek A, Marquez LA, Dobrowsky A, Ratajczak MZ, Cabuhat ML. Differential MMP and TIMP production by human marrow and peripheral blood CD34(+) cells in response to chemokines. Exp Hematol. 2000;28(11):1274–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Clark RE, Bell J, Clark JO, Braithwaite B, Vithanarachchi U, McGinnity N, Callaghan T, Francis S, Salim R. Plerixafor is superior to conventional chemotherapy for first-line stem cell mobilisation, and is effective even in heavily pretreated patients. Blood Cancer J. 2014;4(10):e255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Broxmeyer HE, Orschell CM, Clapp DW, Hangoc G, Cooper S, Plett PA, Liles WC, Li X, Graham-Evans B, Campbell TB, Calandra G, et al. Rapid mobilization of murine and human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. J Exp Med. 2005;201(8):1307–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Broxmeyer HE, Hangoc G, Cooper S, Campbell T, Ito S, Mantel C. AMD3100 and CD26 modulate mobilization, engraftment, and survival of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells mediated by the SDF-1/CXCL12-CXCR4 axis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007June;1106:1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Devine SM, Vij R, Rettig M, Todt L, McGlauchlen K, Fisher N, Devine H, Link DC, Calandra G, Bridger G, Westervelt P, et al. Rapid mobilization of functional donor hematopoietic cells without G-CSF using AMD3100, an antagonist of the CXCR4/SDF-1 interaction. Blood. 2008;112(4):990–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liles WC, Broxmeyer HE, Rodger E, Wood B, Hubel K, Cooper S, Hangoc G, Bridger GJ, Henson GW, Calandra G, Dale DC. Mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells in healthy volunteers by AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. Blood. 2003;102(8):2728–2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liles WC, Rodger E, Broxmeyer HE, Dehner C, Badel K, Calandra G, Christensen J, Wood B, Price TH, Dale DC. Augmented mobilization and collection of CD34+ hematopoietic cells from normal human volunteers stimulated with granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor by single-dose administration of AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. Transfusion. 2005;45(3):295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vishnu P, Roy V, Paulsen A, Zubair AC. Efficacy and cost-benefit analysis of risk-adaptive use of plerixafor for autologous hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization. Transfusion. 2012;52(1):55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li J, Hamilton E, Vaughn L, Graiser M, Renfroe H, Lechowicz MJ, Langston A, Prichard JM, Anderson D, Gleason C, Lonial S, et al. Effectiveness and cost analysis of “just-in-time” salvage plerixafor administration in autologous transplant patients with poor stem cell mobilization kinetics. Transfusion. 2011;51(10):2175–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Costa LJ, Alexander ET, Hogan KR, Schaub C, Fouts TV, Stuart RK. Development and validation of a decision-making algorithm to guide the use of plerixafor for autologous hematopoietic stem cell mobilization. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46(1):64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Maziarz RT, Nademanee AP, Micallef IN, Stiff PJ, Calandra G, Angell J, Dipersio JF, Bolwell BJ. Plerixafor plus granulocyte colony-stimulating factor improves the mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and low circulating peripheral blood CD34+ cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(4):670–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Smith VR, Popat U, Ciurea S, Nieto Y, Anderlini P, Rondon G, Alousi A, Qazilbash M, Kebriaei P, Khouri I, de Lima M, et al. Just-in-time rescue plerixafor in combination with chemotherapy and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor for peripheral blood progenitor cell mobilization. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(9):754–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Farina L, Spina F, Guidetti A, Longoni P, Ravagnani F, Dodero A, Montefusco V, Carlo-Stella C, Corradini P. Peripheral blood CD34+ cell monitoring after cyclophosphamide and granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor: an algorithm for the pre-emptive use of plerixafor. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(2):331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Karpova D, Rettig MP, DiPersio JF. Mobilized peripheral blood: an updated perspective. F1000Res. 2019;8:F1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69(1):11–25. Faculty Rev-2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76(2):301–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Elices MJ, Osborn L, Takada Y, Crouse C, Luhowskyj S, Hemler ME, Lobb RR. VCAM-1 on activated endothelium interacts with the leukocyte integrin VLA-4 at a site distinct from the VLA-4/fibronectin binding site. Cell. 1990;60(4):577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Papayannopoulou T, Nakamoto B. Peripheralization of hemopoietic progenitors in primates treated with anti-VLA4 integrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(20):9374–9378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vermeulen M, Le Pesteur F, Gagnerault MC, Mary JY, Sainteny F, Lepault F. Role of adhesion molecules in the homing and mobilization of murine hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 1998;92(3):894–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brunner S, Zaruba MM, Huber B, David R, Vallaster M, Assmann G, Mueller-Hoecker J, Franz WM. Parathyroid hormone effectively induces mobilization of progenitor cells without depletion of bone marrow. Exp Hematol. 2008;36(9):1157–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ballen KK, Shpall EJ, Avigan D, Yeap BY, Fisher DC, McDermott K, Dey BR, Attar E, McAfee S, Konopleva M, Antin JH, et al. Phase I trial of parathyroid hormone to facilitate stem cell mobilization. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(7):838–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hanel P, Andreani P, Graler MH. Erythrocytes store and release sphingosine 1-phosphate in blood. Faseb j. 2007;21(4):1202–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ohkawa R, Nakamura K, Okubo S, Hosogaya S, Ozaki Y, Tozuka M, Osima N, Yokota H, Ikeda H, Yatomi Y. Plasma sphingosine-1-phosphate measurement in healthy subjects: close correlation with red blood cell parameters. Ann Clin Biochem. 2008;45(Pt 4):356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Schwab SR, Pereira JP, Matloubian M, Xu Y, Huang Y, Cyster JG. Lymphocyte sequestration through S1P lyase inhibition and disruption of S1P gradients. Science. 2005;309(5741):1735–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Massberg S, Schaerli P, Knezevic-Maramica I, Kollnberger M, Tubo N, Moseman EA, Huff IV, Junt T, Wagers AJ, Mazo IB, von Andrian UH. Immunosurveillance by hematopoietic progenitor cells trafficking through blood, lymph, and peripheral tissues. Cell. 2007;131(5):994–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ratajczak MZ, Lee H, Wysoczynski M, Wan W, Marlicz W, Laughlin MJ, Kucia M, Janowska-Wieczorek A, Ratajczak J. Novel insight into stem cell mobilization-plasma sphingosine-1-phosphate is a major chemoattractant that directs the egress of hematopoietic stem progenitor cells from the bone marrow and its level in peripheral blood increases during mobilization due to activation of complement cascade/membrane attack complex. Leukemia. 2010;24(5):976–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lee HM, Wu W, Wysoczynski M, Liu R, Zuba-Surma EK, Kucia M, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ. Impaired mobilization of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in C5-deficient mice supports the pivotal involvement of innate immunity in this process and reveals novel promobilization effects of granulocytes. Leukemia. 2009;23(11):2052–2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Niesvizky R, Mark TM, Ward M, Jayabalan DS, Pearse RN, Manco M, Stern J, Christos PJ, Mathews L, Shore TB, Zafar F, et al. Overcoming the response plateau in multiple myeloma: a novel bortezomib-based strategy for secondary induction and high-yield CD34+ stem cell mobilization. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(6):1534–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Morstyn G, Brown S, Gordon M, Crawford J, Demetri G, Rich W, McGuire B, Foote M, McNiece I. Stem cell factor is a potent synergistic factor in hematopoiesis. Oncology. 1994;51(2):205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Nakamura Y, Tajima F, Ishiga K, Yamazaki H, Oshimura M, Shiota G, Murawaki Y. Soluble c-kit receptor mobilizes hematopoietic stem cells to peripheral blood in mice. Exp Hematol. 2004;32(4):390–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Luens KM, Travis MA, Chen BP, Hill BL, Scollay R, Murray LJ. Thrombopoietin, kit ligand, and flk2/flt3 ligand together induce increased numbers of primitive hematopoietic progenitors from human CD34+ Thy-1+ Lin− cells with preserved ability to engraft SCID-hu bone. Blood. 1998;91(4):1206–1215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. He S, Chu J, Vasu S, Deng Y, Yuan S, Zhang J, Fan Z, Hofmeister CC, He X, Marsh HC. FLT3 L and plerixafor combination increases hematopoietic stem cell mobilization and leads to improved transplantation outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(3):309–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Urdziková L, Likavčanová-Mašínová K, Vaněček V, Růžička J, Šedý J, Syková E, Jendelová P. Flt3 ligand synergizes with granulocyte–colony-stimulating factor in bone marrow mobilization to improve functional outcome after spinal cord injury in the rat. Cytotherapy. 2011;13(9):1090–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Murray L, Luens K, Estrada M, Bruno E, Hoffman R, Cohen R, Ashby M, Vadhan-Raj S. Thrombopoietin mobilizes CD34+ cell subsets into peripheral blood and expands multilineage progenitors in bone marrow of cancer patients with normal hematopoiesis. Exp Hematol. 1998;26(3):207–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hattori K, Heissig B, Tashiro K, Honjo T, Tateno M, Shieh J-H, Hackett NR, Quitoriano MS, Crystal RG, Rafii S. Plasma elevation of stromal cell–derived factor-1 induces mobilization of mature and immature hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells. Blood. 2001;97(11):3354–3360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hattori K, Dias S, Heissig B, Hackett NR, Lyden D, Tateno M, Hicklin DJ, Zhu Z, Witte L, Crystal RG, Moore MA, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietin-1 stimulate postnatal hematopoiesis by recruitment of vasculogenic and hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 2001;193(9):1005–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Moore M, Hattori K, Heissig B, SHIEH JH, Dias S, Crystal R, Rafii S. Mobilization of endothelial and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells by adenovector-mediated elevation of serum levels of SDF-1, VEGF, and angiopoietin-1. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;938(1):36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Pruijt JF, van Kooyk Y, Figdor CG, Lindley IJ, Willemze R, Fibbe WE. Anti–LFA-1 blocking antibodies prevent mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells induced by interleukin-8. Blood. 1998;91(11):4099–4105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Down J, Awwad M, Kurilla-Mahon B, Moran K, Ericsson T, Oldmixon B, Lachance A, Watts A, Treter S, Nash K, Gojo S, et al. Increases in autologous hematopoietic progenitors in the blood of baboons following irradiation and treatment with porcine stem cell factor and interleukin-3. Transplant Proc. 2000;32(5):1045–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Pettengell R, Luft T, De Wynter E, Coutinho L, Young R, Fitzsimmons L, Scarffe JH, Testa NG. Effects of interleukin-6 on mobilization of primitive haemopoietic cells into the circulation. Br J Haematol. 1995;89(2):237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Grzegorzewski K, Komschlies KL, Jacobsen SE, Ruscetti FW, Keller JR, Wiltrout RH. Mobilization of long-term reconstituting hematopoietic stem cells in mice by recombinant human interleukin 7. J Exp Med. 1995;181(1):369–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Jackson JD, Yan Y, Brunda M, Kelsey L, Talmadge JE. Interleukin-12 enhances peripheral hematopoiesis in vivo . Blood. 1995;85(9):2371–2376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Schwarzenberger P, Huang W, Oliver P, Byrne P, La Russa V, Zhang Z, Kolls JK. IL-17 mobilizes peripheral blood stem cells with short-and long-term repopulating ability in mice. J Immunol. 2001;167(4):2081–2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Alt C, Yuan S, Wu F, Stankovich B, Calaoagan J, Schopies S, Wu JY, Shen J, Schneider D, Zhu Y. Long-acting IL-33 mobilizes high-quality hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells more efficiently than granulocyte colony-stimulating factor or AMD3100. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(8):1475–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Pelus LM, Bian H, Fukuda S, Wong D, Merzouk A, Salari H. The CXCR4 agonist peptide, CTCE-0021, rapidly mobilizes polymorphonuclear neutrophils and hematopoietic progenitor cells into peripheral blood and synergizes with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Exp Hematol. 2005;33(3):295–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Karpova D, Rettig MP, Ritchey J, Cancilla D, Christ S, Gehrs L, Chendamarai E, Evbuomwan MO, Holt M, Zhang J, Abou-Ezzi G, et al. Targeting VLA4 integrin and CXCR2 mobilizes serially repopulating hematopoietic stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(7):2745–2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Fukuda S, Bian H, King AG, Pelus LM. The chemokine GRObeta mobilizes early hematopoietic stem cells characterized by enhanced homing and engraftment. Blood. 2007;110(3):860–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Pruijt JF, Fibbe WE, Laterveer L, Pieters RA, Lindley IJ, Paemen L, Masure S, Willemze R, Opdenakker G. Prevention of interleukin-8-induced mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells in rhesus monkeys by inhibitory antibodies against the metalloproteinase gelatinase B (MMP-9). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(19):10863–10868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Laterveer L, Lindley IJ, Heemskerk DP, Camps JA, Pauwels EK, Willemze R, Fibbe WE. Rapid mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells in rhesus monkeys by a single intravenous injection of interleukin-8. Blood. 1996;87(2):781–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Cancelas JA, Lee AW, Prabhakar R, Stringer KF, Zheng Y, Williams DA. Rac GTPases differentially integrate signals regulating hematopoietic stem cell localization. Nat Med. 2005;11(8):886–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ghiaur G, Lee A, Bailey J, Cancelas JA, Zheng Y, Williams DA. Inhibition of RhoA GTPase activity enhances hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell proliferation and engraftment. Blood. 2006;108(6):2087–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ratajczak MZ, Suszynska M, Borkowska S, Ratajczak J, Schneider G. The role of sphingosine-1 phosphate and ceramide-1 phosphate in trafficking of normal stem cells and cancer cells. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2014;18(1):95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Velders GA, van Os R, Hagoort H, Verzaal P, Guiot HF, Lindley IJ, Willemze R, Opdenakker G, Fibbe WE. Reduced stem cell mobilization in mice receiving antibiotic modulation of the intestinal flora: involvement of endotoxins as cofactors in mobilization. Blood. 2004;103(1):340–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Molendijk W, van Oudenaren A, van Dijk H, Daha M, Benner R. Complement split product C5a mediates the lipopolysaccharide-induced mobilization of CFU-s and haemopoietic progenitor cells, but not the mobilization induced by proteolytic enzymes. Cell Proliferation. 1986;19(4):407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Schneider OD, Weiss AA, Miller WE. Pertussis toxin signals through the TCR to initiate cross-desensitization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J Immunol. 2009;182(9):5730–5739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Fehér I, Gidáli J. Mobilizable stem cells: characteristics and replacement of the pool after exhaustion. Exp Hematol. 1982;10(8):661–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Hoggatt J, Singh P, Tate TA, Chou B-K, Datari SR, Fukuda S, Liu L, Kharchenko PV, Schajnovitz A, Baryawno N. Rapid mobilization reveals a highly engraftable hematopoietic stem cell. Cell. 2018;172(1-2):191–204. e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Christopherson KW, 2nd, Cooper S, Broxmeyer HE. Cell surface peptidase CD26/DPPIV mediates G-CSF mobilization of mouse progenitor cells. Blood. 2003;101(12):4680–4686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Lévesque J-P, Hendy J, Takamatsu Y, Simmons PJ, Bendall LJ. Disruption of the CXCR4/CXCL12 chemotactic interaction during hematopoietic stem cell mobilization induced by GCSF or cyclophosphamide. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(2):187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Bonig H, Watts KL, Chang KH, Kiem HP, Papayannopoulou T. Concurrent blockade of α4-integrin and CXCR4 in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell mobilization. Stem Cells. 2009;27(4):836–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ramirez P, Rettig MP, Uy GL, Deych E, Holt MS, Ritchey JK, DiPersio JF. BIO5192, a small molecule inhibitor of VLA-4, mobilizes hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 2009;114(7):1340–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Cao B, Zhang Z, Grassinger J, Williams B, Heazlewood CK, Churches QI, James SA, Li S, Papayannopoulou T, Nilsson SK. Therapeutic targeting and rapid mobilization of endosteal HSC using a small molecule integrin antagonist. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Kikuta T, Shimazaki C, Ashihara E, Sudo Y, Hirai H, Sumikuma T, Yamagata N, Inaba T, Fujita N, Kina T. Mobilization of hematopoietic primitive and committed progenitor cells into blood in mice by anti-vascular adhesion molecule-1 antibody alone or in combination with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Exp Hematol. 2000;28(3):311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Zöller M. CD44v10 in hematopoiesis and stem cell mobilization. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;38(5-6):463–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Sweeney EA, Priestley GV, Nakamoto B, Collins RG, Beaudet AL, Papayannopoulou T. Mobilization of stem/progenitor cells by sulfated polysaccharides does not require selectin presence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(12):6544–6549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Sweeney EA, Lortat-Jacob H, Priestley GV, Nakamoto B, Papayannopoulou T. Sulfated polysaccharides increase plasma levels of SDF-1 in monkeys and mice: involvement in mobilization of stem/progenitor cells. Blood. 2002;99(1):44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Patchen ML, Liang J, Vaudrain T, Martin T, Melican D, Zhong S, Stewart M, Quesenberry PJ. Mobilization of Peripheral Blood Progenitor Cells by Betafectin® PGG-Glucan Alone and in Combination with Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor. Stem Cells. 1998;16(3):208–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Albanese P, Caruelle D, Frescaline G, Delbé J, Petit-Cocault L, Huet E, Charnaux N, Uzan G, Papy-Garcia D, Courty J. Glycosaminoglycan mimetics–induced mobilization of hematopoietic progenitors and stem cells into mouse peripheral blood: structure/function insights. Exp Hematol. 2009;37(9):1072–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Carlo-Stella C, Di Nicola M, Magni M, Longoni P, Milanesi M, Stucchi C, Cleris L, Formelli F, Gianni MA. Defibrotide in combination with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor significantly enhances the mobilization of primitive and committed peripheral blood progenitor cells in mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62(21):6152–6157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Hoggatt J, Mohammad KS, Singh P, Hoggatt AF, Chitteti BR, Speth JM, Hu P, Poteat BA, Stilger KN, Ferraro F. Differential stem-and progenitor-cell trafficking by prostaglandin E 2. Nature. 2013;495(7441):365–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Niesvizky R, Mark TM, Ward M, Jayabalan DS, Pearse RN, Manco M, Stern J, Christos PJ, Mathews L, Shore TB. Overcoming the response plateau in multiple myeloma: a novel bortezomib-based strategy for secondary induction and high-yield CD34+ stem cell mobilization. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(6):1534–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Saez B, Ferraro F, Yusuf RZ, Cook CM, Yu VW, Pardo-Saganta A, Sykes SM, Palchaudhuri R, Schajnovitz A, Lotinun S, Lymperi S, et al. Inhibiting stromal cell heparan sulfate synthesis improves stem cell mobilization and enables engraftment without cytotoxic conditioning. Blood. 2014;124(19):2937–2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Forristal CE, Nowlan B, Jacobsen RN, Barbier V, Walkinshaw G, Walkley CR, Winkler IG, Levesque JP. HIF-1alpha is required for hematopoietic stem cell mobilization and 4-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors enhance mobilization by stabilizing HIF-1alpha. Leukemia. 2015;29(6):1366–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Ting MJ, Day BW, Spanevello MD, Boyd AW. Activation of ephrin A proteins influences hematopoietic stem cell adhesion and trafficking patterns. Exp Hematol. 2010;38(11):1087–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Lenkiewicz AM, Adamiak M, Thapa A, Bujko K, Pedziwiatr D, Abdel-Latif AK, Kucia M, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ. The Nlrp3 inflammasome orchestrates mobilization of bone marrow-residing stem cells into peripheral blood. Stem Cell Rev Rep.2019;15(3):391–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Wang W, Yu S, Myers J, Wang Y, Xin WW, Albakri M, Xin AW, Li M, Huang AY, Xin W, Siebel CW, et al. Notch2 blockade enhances hematopoietic stem cell mobilization and homing. Haematologica. 2017;102(10):1785–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Gaiano N, Fishell G. The role of notch in promoting glial and neural stem cell fates. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:471–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Bolos V, Grego-Bessa J, de la Pompa JL. Notch signaling in development and cancer. Endocr Rev. 2007;28(3):339–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Aguirre A, Rubio ME, Gallo V. Notch and EGFR pathway interaction regulates neural stem cell number and self-renewal. Nature. 2010;467(7313):323–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Hitoshi S, Alexson T, Tropepe V, Donoviel D, Elia AJ, Nye JS, Conlon RA, Mak TW, Bernstein A, van der Kooy D. Notch pathway molecules are essential for the maintenance, but not the generation, of mammalian neural stem cells. Genes Dev. 2002;16(7):846–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Liu ZJ, Shirakawa T, Li Y, Soma A, Oka M, Dotto GP, Fairman RM, Velazquez OC, Herlyn M. Regulation of Notch1 and Dll4 by vascular endothelial growth factor in arterial endothelial cells: implications for modulating arteriogenesis and angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(1):14–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Grego-Bessa J, Luna-Zurita L, del Monte G, Bolos V, Melgar P, Arandilla A, Garratt AN, Zang H, Mukouyama YS, Chen H, Shou W, et al. Notch signaling is essential for ventricular chamber development. Dev Cell. 2007;12(3):415–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Nobta M, Tsukazaki T, Shibata Y, Xin C, Moriishi T, Sakano S, Shindo H, Yamaguchi A. Critical regulation of bone morphogenetic protein-induced osteoblastic differentiation by Delta1/Jagged1-activated Notch1 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(16):15842–15848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Wang W, Zimmerman G, Huang X, Yu S, Myers J, Wang Y, Moreton S, Nthale J, Awadallah A, Beck R, Xin W, et al. Aberrant Notch Signaling in the Bone Marrow Microenvironment of Acute Lymphoid Leukemia Suppresses Osteoblast-Mediated Support of Hematopoietic Niche Function. Cancer Res. 2016;76(6):1641–1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Zhou L, Li LW, Yan Q, Petryniak B, Man Y, Su C, Shim J, Chervin S, Lowe JB. Notch-dependent control of myelopoiesis is regulated by fucosylation. Blood. 2008;112(2):308–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Sorrentino C, Cuneo A, Roti G. Therapeutic targeting of notch signaling pathway in hematological malignancies. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2019;11(1):e2019037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Fehon RG, Kooh PJ, Rebay I, Regan CL, Xu T, Muskavitch MA, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Molecular interactions between the protein products of the neurogenic loci Notch and Delta, two EGF-homologous genes in Drosophila. Cell. 1990;61(3):523–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Rebay I, Fleming RJ, Fehon RG, Cherbas L, Cherbas P, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Specific EGF repeats of Notch mediate interactions with Delta and Serrate: implications for Notch as a multifunctional receptor. Cell. 1991;67(4):687–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Dumortier A, Wilson A, MacDonald HR, Radtke F. Paradigms of notch signaling in mammals. Int J Hematol. 2005;82(4):277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. De Strooper B, Annaert W, Cupers P, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Mumm JS, Schroeter EH, Schrijvers V, Wolfe MS, Ray WJ, Goate A, et al. A presenilin-1-dependent gamma-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain. Nature. 1999;398(6727):518–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Jeffries S, Robbins DJ, Capobianco AJ. Characterization of a high-molecular-weight Notch complex in the nucleus of Notch(ic)-transformed RKE cells and in a human T-cell leukemia cell line. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(11):3927–3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Duncan AW, Rattis FM, DiMascio LN, Congdon KL, Pazianos G, Zhao C, Yoon K, Cook JM, Willert K, Gaiano N, Reya T. Integration of Notch and Wnt signaling in hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(3):314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Karanu FN, Murdoch B, Gallacher L, Wu DM, Koremoto M, Sakano S, Bhatia M. The notch ligand jagged-1 represents a novel growth factor of human hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192(9):1365–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Stier S, Cheng T, Dombkowski D, Carlesso N, Scadden DT. Notch1 activation increases hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal in vivo and favors lymphoid over myeloid lineage outcome. Blood. 2002;99(7):2369–2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Varnum-Finney B, Xu L, Brashem-Stein C, Nourigat C, Flowers D, Bakkour S, Pear WS, Bernstein ID. Pluripotent, cytokine-dependent, hematopoietic stem cells are immortalized by constitutive Notch1 signaling. Nat Med. 2000;6(11):1278–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Maillard I, Koch U, Dumortier A, Shestova O, Xu L, Sai H, Pross SE, Aster JC, Bhandoola A, Radtke F, Pear WS. Canonical notch signaling is dispensable for the maintenance of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(4):356–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Mancini SJ, Mantei N, Dumortier A, Suter U, MacDonald HR, Radtke F. Jagged1-dependent Notch signaling is dispensable for hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Blood. 2005;105(6):2340–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Varnum-Finney B, Halasz LM, Sun M, Gridley T, Radtke F, Bernstein ID. Notch2 governs the rate of generation of mouse long- and short-term repopulating stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(3):1207–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Poulos MG, Guo P, Kofler NM, Pinho S, Gutkin MC, Tikhonova A, Aifantis I, Frenette PS, Kitajewski J, Rafii S, Butler JM. Endothelial Jagged-1 is necessary for homeostatic and regenerative hematopoiesis. Cell Rep. 2013;4(5):1022–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Yu VW, Saez B, Cook C, Lotinun S, Pardo-Saganta A, Wang YH, Lymperi S, Ferraro F, Raaijmakers MH, Wu JY, Zhou L, et al. Specific bone cells produce DLL4 to generate thymus-seeding progenitors from bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2015;212(5):759–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Yao D, Huang Y, Huang X, Wang W, Yan Q, Wei L, Xin W, Gerson S, Stanley P, Lowe JB, Zhou L. Protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 (Pofut1) regulates lymphoid and myeloid homeostasis through modulation of Notch receptor ligand interactions. Blood. 2011;117(21):5652–5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Oh P, Lobry C, Gao J, Tikhonova A, Loizou E, Manent J, van Handel B, Ibrahim S, Greve J, Mikkola H, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, et al. In vivo mapping of notch pathway activity in normal and stress hematopoiesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13(2):190–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Moloney DJ, Shair LH, Lu FM, Xia J, Locke R, Matta KL, Haltiwanger RS. Mammalian Notch1 is modified with two unusual forms of O-linked glycosylation found on epidermal growth factor-like modules. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(13):9604–9611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Rana NA, Nita-Lazar A, Takeuchi H, Kakuda S, Luther KB, Haltiwanger RS. O-glucose trisaccharide is present at high but variable stoichiometry at multiple sites on mouse Notch1. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(36):31623–31637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Shao L, Moloney DJ, Haltiwanger R. Fringe modifies O-fucose on mouse Notch1 at epidermal growth factor-like repeats within the ligand-binding site and the Abruptex region. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(10):7775–7782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Acar M, Jafar-Nejad H, Takeuchi H, Rajan A, Ibrani D, Rana NA, Pan H, Haltiwanger RS, Bellen HJ. Rumi is a CAP10 domain glycosyltransferase that modifies Notch and is required for Notch signaling. Cell. 2008;132(2):247–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Okajima T, Irvine KD. Regulation of notch signaling by o-linked fucose. Cell. 2002;111(6):893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Wang Y, Shao L, Shi S, Harris RJ, Spellman MW, Stanley P, Haltiwanger RS. Modification of epidermal growth factor-like repeats with O-fucose. molecular cloning and expression of a novel GDP-fucose protein O-fucosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(43):40338–40345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Luo Y, Haltiwanger RS. O-fucosylation of notch occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(12):11289–11294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Okajima T, Xu A, Irvine KD. Modulation of notch-ligand binding by protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 and fringe. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(43):42340–42345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Shi S, Stanley P. Protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 is an essential component of Notch signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(9):5234–5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Okamura Y, Saga Y. Pofut1 is required for the proper localization of the Notch receptor during mouse development. Mech Dev. 2008;125(8):663–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Luca VC, Kim BC, Ge C, Kakuda S, Wu D, Roein-Peikar M, Haltiwanger RS, Zhu C, Ha T, Garcia KC. Notch-Jagged complex structure implicates a catch bond in tuning ligand sensitivity. Science. 2017;355(6331):1320–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Luca VC, Jude KM, Pierce NW, Nachury MV, Fischer S, Garcia KC. Structural biology. structural basis for Notch1 engagement of Delta-like 4. Science. 2015;347(6224):847–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Chen J, Moloney DJ, Stanley P. Fringe modulation of Jagged1-induced Notch signaling requires the action of beta 4galactosyltransferase-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(24):13716–13721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Taylor P, Takeuchi H, Sheppard D, Chillakuri C, Lea SM, Haltiwanger RS, Handford PA. Fringe-mediated extension of O-linked fucose in the ligand-binding region of Notch1 increases binding to mammalian Notch ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(20):7290–7295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Rampal R, Li AS, Moloney DJ, Georgiou SA, Luther KB, Nita-Lazar A, Haltiwanger RS. Lunatic fringe, manic fringe, and radical fringe recognize similar specificity determinants in O-fucosylated epidermal growth factor-like repeats. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(51):42454–42463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Shimizu K, Chiba S, Saito T, Kumano K, Takahashi T, Hirai H. Manic fringe and lunatic fringe modify different sites of the Notch2 extracellular region, resulting in different signaling modulation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(28):25753–25758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Myers J, Huang Y, Wei L, Yan Q, Huang A, Zhou L. Fucose-deficient hematopoietic stem cells have decreased self-renewal and aberrant marrow niche occupancy. Transfusion. 2010;50(12):2660–2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Wang W, Yu S, Zimmerman G, Wang Y, Myers J, Yu VW, Huang D, Huang X, Shim J, Huang Y, Xin W, et al. Notch Receptor-Ligand Engagement Maintains Hematopoietic Stem Cell Quiescence and Niche Retention. Stem Cells. 2015;33(7):2280–2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Wu Y, Cain-Hom C, Choy L, Hagenbeek TJ, de Leon GP, Chen Y, Finkle D, Venook R, Wu X, Ridgway J, Schahin-Reed D, et al. Therapeutic antibody targeting of individual Notch receptors. Nature. 2010;464(7291):1052–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Tran IT, Sandy AR, Carulli AJ, Ebens C, Chung J, Shan GT, Radojcic V, Friedman A, Gridley T, Shelton A, Reddy P, et al. Blockade of individual Notch ligands and receptors controls graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(4):1590–1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P, Bringhurst FR, Milner LA, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425(6960):841–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Weber JM, Forsythe SR, Christianson CA, Frisch BJ, Gigliotti BJ, Jordan CT, Milner LA, Guzman ML, Calvi LM. Parathyroid hormone stimulates expression of the Notch ligand Jagged1 in osteoblastic cells. Bone. 2006;39(3):485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Guezguez B, Campbell CJ, Boyd AL, Karanu F, Casado FL, Di Cresce C, Collins TJ, Shapovalova Z, Xenocostas A, Bhatia M. Regional localization within the bone marrow influences the functional capacity of human HSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13(2):175–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Pusic I, Jiang SY, Landua S, Uy GL, Rettig MP, Cashen AF, Westervelt P, Vij R, Abboud CN, Stockerl-Goldstein KE, Sempek DS, et al. Impact of mobilization and remobilization strategies on achieving sufficient stem cell yields for autologous transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(9):1045–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167. Mohty M, Hubel K, Kroger N, Aljurf M, Apperley J, Basak GW, Bazarbachi A, Douglas K, Gabriel I, Garderet L, Geraldes C, et al. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell mobilisation in multiple myeloma and lymphoma patients: a position statement from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(7):865–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Moskowitz CH, Glassman JR, Wuest D, Maslak P, Reich L, Gucciardo A, Coady-Lyons N, Zelenetz AD, Nimer SD. Factors affecting mobilization of peripheral blood progenitor cells in patients with lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4(2):311–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169. Moreb JS, Salmasinia D, Hsu J, Hou W, Cline C, Rosenau E. Long-term outcome after autologous stem cell transplantation with adequate peripheral blood stem cell mobilization using plerixafor and G-CSF in poor mobilizer lymphoma and myeloma patients. Adv Hematol. 2011;2011:517561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170. Keating GM. Plerixafor: a review of its use in stem-cell mobilization in patients with lymphoma or multiple myeloma. Drugs. 2011;71(12):1623–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Cecyn KZ, Seber A, Ginani VC, Goncalves AV, Caram EM, Oguro T, Oliveira OM, Carvalho MM, Bordin JO. Large-volume leukapheresis for peripheral blood progenitor cell collection in low body weight pediatric patients: a single center experience. Transfus Apher Sci. 2005;32(3):269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172. Bojanic I, Dubravcic K, Batinic D, Cepulic BG, Mazic S, Hren D, Nemet D, Labar B. Large volume leukapheresis: efficacy and safety of processing patient’s total blood volume six times. Transfus Apher Sci. 2011;44(2):139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173. Michon B, Moghrabi A, Winikoff R, Barrette S, Bernstein ML, Champagne J, David M, Duval M, Hume HA, Robitaille N, Belisle A, et al. Complications of apheresis in children. Transfusion. 2007;47(10):1837–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]