Abstract

Simple Summary

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) can be safely discontinued in chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Achieving a sustained deep molecular response (DMR) before stop is recommended. Currently, the proportion of patients who achieve a sustained DMR remains to be determined. Based on the follow-up of 398 patients over a ten-years period, we evaluate that 46% of them have achieved a sustained DMR. Gender, BCR-ABL1 transcript type, and disease risk scores were significantly associated with the probability of achieving a DMR. 95/398 (24%) patients stopped TKI with a probability of maintaining molecular reponse without TKI resumption of 47% at 48 months after stop. In this study, TKI duration before stop and second (nilotinib, dasatinib, bosutinib) generation frontline TKI compared to imatinib were significantly associated with a lower risk of molecular relapse after stop in patients who have achieved a sustained DMR.

Abstract

Background: Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs) discontinuation in patients who had achieved a deep molecular response (DMR) offer now the opportunity of prolonged treatment-free remission (TFR). Patients and Methods: Aims of this study were to evaluate the proportion of de novo chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CP-CML) patients who achieved a sustained DMR and to identify predictive factors of DMR and molecular recurrence-free survival (MRFS) after TKI discontinuation. Results: Over a period of 10 years, 398 CP-CML patients treated with first-line TKIs were included. Median age at diagnosis was 61 years, 291 (73%) and 107 (27%) patients were treated with frontline imatinib (IMA) or second- or third-generation TKIs (2–3G TKI), respectively. With a median follow-up of seven years (range, 0.6 to 13.8 years), 182 (46%) patients achieved a sustained DMR at least 24 months. Gender, BCR-ABL1 transcript type, and Sokal and ELTS risk scores were significantly associated with a higher probability of sustained DMR while TKI first-line (IMA vs. 2–3G TKI) was not. We estimate that 28% of CML-CP would have been an optimal candidate for TKI discontinuation according to recent recommendations. Finally, 95 (24%) patients have entered in a TFR program. MRFS rates at 12 and 48 months were 55.1% (95% CI, 44.3% to 65.9%) and 46.9% (95% CI, 34.9% to 58.9%), respectively. In multivariate analyses, first-line 2–3G TKIs compared to IMA and TKI duration were the most significant factors of MRFS. Conclusions: Our results suggest that frontline TKIs have a significant impact on TFR in patients who fulfill the selection criteria for TKI discontinuation.

Keywords: chronic myeloid leukemia, tyrosine kinase inhibitor, deep molecular responses, treatment-free remission

1. Introduction

Targeting the deregulated tyrosine kinase activity of the BCR-ABL1 fusion protein with selective agents, namely the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients constitutes one of the most impressive therapeutic progress over the past 20 years. With the exception of a minority of patients diagnosed in the late phase of the disease or patients who progress on TKIs, most patients achieve a response associated with a very low risk of disease progression and an overall survival close to the healthy population [1,2,3,4]. The main treatment goals in chronic phase CML (CP-CML) patients are now to minimize the risks associated with TKI in the long-term issue and to avoid lifelong TKI exposure.

Several published studies have demonstrated that TKIs can be safely discontinued in CP-CML patients who have achieved a sustained deep molecular response (DMR) from therapy with an overall likelihood of maintaining a major molecular response (MMR) of 40 to 70% after TKI cessation (Review in Dulucq et al. and Cortes et al. [5,6]). Indeed, TKI resumption after the loss of MMR leads to a second DMR in most if not all patients provided that TKI had been restarted and the follow-up after resumption is sufficient [7,8,9,10,11]. The depth and duration of DMR, as well as TKI duration before discontinuation, are essential factors for a successful attempt. Currently, achieving an MR4.5 log reduction in the BCR-ABL1/ABL1 ratio during at least two years or an MR4 log reduction lasting more than three years before stopping together with an M BCR-ABL1 transcript, chronic phase at diagnosis and the absence of suboptimal response or failure during TKI treatments are recommended for TKI discontinuation outside a clinical trial [12,13,14]. Less stringent criteria are still under evaluation in some ongoing clinical trials [15,16,17]. It has been estimated that 28 to 36% of CP-CML patients receiving imatinib frontline or after interferon achieved a sustained DMR defined as BCR-ABL1/ABL1 4 log (MR4) or 4.5 (MR4.5) log reduction sustained for at least two years [18,19]. Based on the results of frontline randomized clinical trials, second-generation TKIs, i.e., dasatinib and nilotinib ten years ago and more recently bosutinib, have been approved as first-line therapeutic options [20,21,22]. Final updates of the Dasatinib vs. the Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naïve Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients Trial (DASISION) and the Evaluating Nilotinib Efficacy and Safety in Clinical Trials-Newly Diagnosed Patients (ENESTnd) demonstrated that frontline second-generation TKIs were associated with higher cumulative incidences of DMR compared to imatinib [23,24].

However, maintenance and duration of these DMR are unknown. Hence, currently, the proportion of CML patients receiving frontline TKIs who achieve a sustained DMR needs to be re-evaluated. We conducted a multicenter, retrospective, and observational study. The primary objective was to assess in de novo TKI CP-CML patients the incidence and predictive factors of sustained DMR. The secondary objective was to evaluate the rate and predictive factors of molecular recurrence-free survival (MRFS) in patients who discontinued TKIs.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

From January 2006 to December 2015, we included adult patients (≥18 years old), diagnosed in CP of the disease and treated with any first-line TKI at any dose in the 9 southwest French participating centers. Patients who received frontline TKIs within clinical trials were not excluded. All patients agreed to be included in this observational study and provided informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Definitions

Chronic, accelerated, and blastic phases of the disease (CP, AP, and BP) as well as responses, overall and progression survivals were defined in line with the ELN recommendations [25,26]. Deaths were considered CML-related when occurred in AP or BP and related to the progression of the disease. Sokal and EUTOS Long-Term Survival (ELTS) risk scores were calculated according to the proposed formulations [27,28]. The molecular response was assessed by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and reported as ratios of BCR-ABL1 to ABL1 standardized to the international scale (IS) (BCR-ABLIS) according to previously reported recommendations [29,30]. All BCR-ABL1/ABL1 assessments were performed in a unique central laboratory belonging to the Groupe des Biologistes Moléculaires des Hémopathies Malignes (GBMHM) and European Treatment Outcome Study (EUTOS) labs group. BCR-ABL1/ABL1 assessments were performed every 3 to 4 months and MMR, MR4, and MR4.5 were defined as 3-log reduction or BCR-ABL1IS ≤ 0.1%, 4-log reduction or BCR-ABL1IS ≤ 0.01%, and 4.5-log reduction or BCR-ABL1IS ≤ 0.0032%, respectively.

Each molecular response had to be confirmed on two consecutive analyses at least two months apart. The date of each molecular response corresponds to the first date of obtaining a molecular response. MR4.5 was defined as sustained if no more than one BCR-ABL1IS assessment in a twelve-month period demonstrated an MR4.5 loss with retained MR4. Molecular follow-up after TKI discontinuation was performed as recommended [13]. Molecular recurrence after TKI discontinuation was defined either as a confirmed positivity of BCR-ABL1IS with an increase of one log on two consecutive assessments or MMR loss. In the case of molecular recurrence, restart TKI used before discontinuation was recommended. Molecular recurrence-free survival was measured from the date of TKI stop to the date of the first event, i.e., molecular recurrence or death, or to the date of last available follow-up.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Quantitative variables were described using the median and the range (min – max). For qualitative parameters, the results were presented as numbers (proportions). Qualitative and quantitative variables were compared according to frontline TKI type or the occurrence of molecular recurrence using Chi-square or Fisher exact tests for qualitative variables and Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for quantitative parameters. Baseline patients’ characteristics such as gender (female vs. male), age, BCR-ABL1 transcript (B3A2 vs. each type), additional cytogenetic abnormalities vs. none, Sokal and ELTS (low vs. Intermediate, low vs. high) risk scores, first-line TKI (IMA vs. 2–3G TKI) were analyzed as potential factors for achieving MR4.5, MR4.5 sustained more than 24 months, or for experiencing molecular recurrence after TKI discontinuation. Ongoing characteristics (e.g., duration of TKI treatment, time to MR4.5, MR4.5 duration, history of TKI switch due to intolerance or lack of efficacy) were also tested as prognostic factors for molecular recurrence. Associations between MR4.5 and sustained MR4.5 and the variables were analyzed using the competing risks method. Allogenic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (AHSCT) or death without DMR were considered as competing events. The effect of covariates was estimated using the Fine and Gray model. The proportional hazard assumption was tested using the Lin test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using Cox regression to analyze factors associated with the molecular recurrence because of no competing events to the occurrence of molecular recurrence. Variables were included in the multivariate analysis if they were significantly associated with the outcome in the univariate analysis (p < 0.05) or if they were clinically relevant based on previously published results.

To establish factors associated with molecular recurrence, patients with TKI cessation for efficacy only and with a follow up of at least 6 months after discontinuation were analyzed.

Results were presented as subdistribution hazard ratios (SHR) with their 95% confidence interval.

Cumulative incidences of DMR (MR4.5 and sustained MR4.5) were measured from frontline TKI start to the date of confirmed MR4.5 or to the date from which MR4.5 remained sustained and were compared using the Gray test. Molecular recurrence-free survival (MRFS) was measured from the date of TKI discontinuation to the date of molecular recurrence or the last follow-up for patients who did not relapse. MRFS was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and survival differences were assessed using a log-rank test. Progression-free survival (PFS) from TKI start to the day of AP or BP phase or death, and overall survival (OS) were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method.

All statistical analyses were carried with R software and IBM® SPSS software, version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The statistical significance level was (two-sided) 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

From January 2006 to December 2015, 398 CML patients in CP at diagnosis were recruited in the nine southwest French participating centers and were included in the study. The baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis and the proportion of high Sokal risk score significantly differ between patients receiving frontline 2–3G TKIs or IMA.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (N = 398 patients).

| Characteristics | All Patients (N = 398) |

Frontline IMA Patients (N = 291) |

Frontline 2–3G TKI Patients (N = 107) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at diagnosis, years (range) | 61.6 (18.6–90.2) | 63.9 (18.6–90.2) | 54.0 (22.7–82.9) | <0.001 |

| ≥70, n pts (%) <45, n pts (%) |

106 (26.6) 77 (19.3) |

94 (32.3) 40 (13.7) |

12 (11.2) 37 (34.5) |

<0.001 <0.001 |

| Gender, female, n pts (%) | 168 (42.2) | 123 (42.2) | 45 (42.0) | 0.532 |

| Sokal risk score, n pts (%) | 0.022 | |||

| Low | 112 (28.1) | 81 (27.8) | 31 (28.9) | |

| Intermediate | 193 (49.7) | 149 (51.2) | 44 (41.2) | |

| High | 76 (19.0) | 46 (15.8) | 30 (28.0) | |

| Unknown | 17 (4.2) | 15 (5.1) | 2 (1.8) | |

| ELTS risk score, n pts (%) | 0.054 | |||

| Low | 199 (50.0) | 138 (47.7) | 61 (56.0) | |

| Intermediate | 122 (30.6) | 98 (33.3) | 24 (23.3) | |

| High | 53 (13.3) | 35 (12.0) | 18 (16.8) | |

| Unknown | 24 (6.0) | 20 (6.8) | 4 (3.7) | |

| Non-M BCR-ABL1 transcript, n pts | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0.373 |

| ACA at diagnosis, n pts (%) | 30 (7.5) | 22 (7.5) | 8 (7.4) | 0.584 |

| ACA major route at diagnosis, n pts (%) | 12 (3.0) | 8 (2.7) | 4 (3.7) | 0.410 |

| First-line TKI type and initial daily dose, n pts (%) | ||||

| Imatinib 400 | 276 (69.3) | 276 (94.8) | NA | |

| Imatinib > 400 | 7 (1.7) | 7 (2.4) | NA | |

| Imatinib < 400 | 8 (2.0) | 8 (2.7) | NA | |

| Nilotinib 600 | 69 (17.3) | NA | 69 (64.4) | |

| Nilotinib 800 | 8 (2.0) | NA | 8 (7.4) | |

| Dasatinib 100 | 26 (6.5) | NA | 26 (24.3) | |

| Bosutinib 500 | 2 (0.5) | NA | 2 (1.8) | |

| Ponatinib 45 | 2 (0.5) | NA | 2 (1.8) |

Abbreviations: IMA, Imatinib; TKI, Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor; 2–3G TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor of second and third generation; pts, patients; ACA, Additional Cytogenetic Abnormalities; NA, Not Applicable.

3.2. Outcome

The median follow-up from diagnosis to last date of follow-up or death was seven years (range: 0.6 to 13.8). Seventeen (4.2%) patients have progressed to AP or BP of the disease. Sixteen (4%) patients underwent AHSCT while in the first chronic phase (n = 8) or after progression to AP or BP (n = 8), whereas one patient progressed to myeloid blast crisis during year six—all the progression events occurred during the four years following CML diagnosis. Sixty (15%) patients died. Ten deaths were considered as CML-related (myeloid blast crisis in nine patients, lymphoid in one). Fifty patients died due to CML-unrelated causes (secondary neoplasm, n = 18; cardiovascular diseases, n = 10; non-cardiac chronic organ failures, n = 13; death related to AHSCT, n = 4; infectious diseases, n = 3; suicide, n = 1; unknown, n = 1). Five- and 10-year overall and progression-free survivals are 90% (95% confidence interval (CI 95%) CI, 87.06% to 92.94%) and 81% (95% CI, 76.0% to 85.8%), and 88% (95% CI, 85.16% to 91.44%) and 79% (95% CI, 74.4% to 84.2%), respectively.

3.2.1. Cumulative Incidences of Deep Molecular Responses (MR4.5 and Sustained MR4.5 at Least 24 Months)

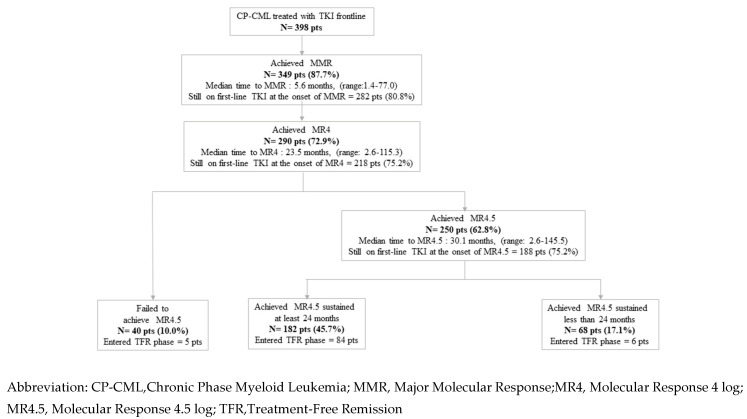

Overall, 349 (87%) patients achieved an MMR, 290 (72%) an MR4, and 250 (62%) an MR4.5. The median times from TKI start to molecular response were 9.3 months (range: 1.4 to 84.2) for MMR, 23.5 months (range: 2.6 to 115.3) for MR4, and 30.1 months (range: 2.6 to 145.5) for MR4.5. The proportion of patients still on first-line TKI was 80% at the time of MMR, 75% at the time of MR4, and 75% at the time of MR4.5. Incidences of MMR, MR4, MR4.5, and sustained MR4.5 of at least 24 months and TKI discontinuation are summarized in the flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of molecular response (major molecular response, molecular response 4 log, molecular response 4.5 log, molecular response 4.5 log sustained at least 24 months) and TKI discontinuation (N = 398 pts).

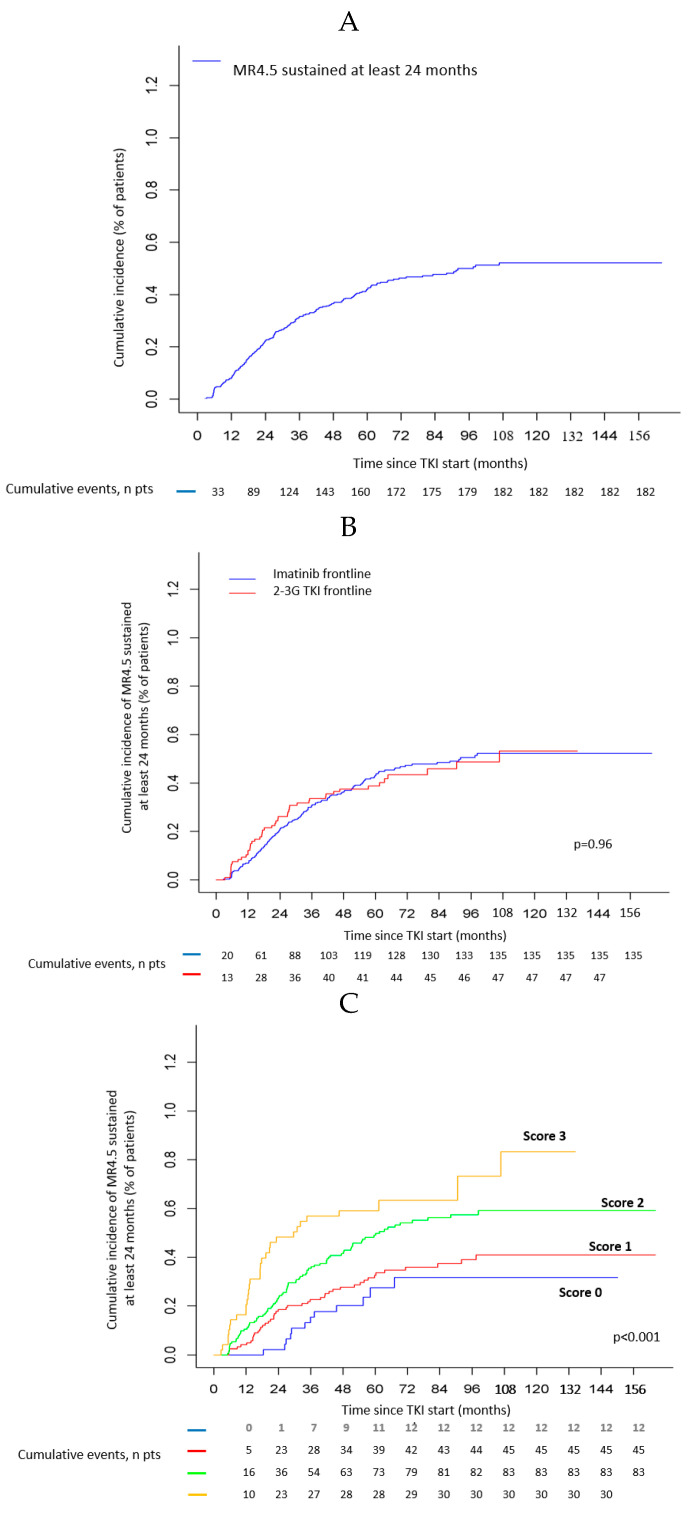

Finally, 182 (46%) patients experienced a sustained MR4 with a median time from TKI start to the onset of sustained MR4.5 of 25.5 months (range: 2.6 to 106.7). The cumulative incidence of sustained MR4.5 for the whole study population is presented in Figure 2A.

Figure 2.

(A): Cumulative incidence of molecular response 4.5 log sustained for at least 24 months (N = 398 patients). (B): Cumulative incidence of sustained molecular response 4.5 log of at least 24 months according to first-line TKIs (Imatinib vs. 2nd or 3rd generation TKI). (C): Cumulative incidences of sustained MR4.5 of at least 24 months according to predictive factors. For each positive factor, female gender, B3A2 BCR-ABL1 transcript type, and low risk ELTS score, one point is scored. The sum of points defined as the number of positive factors (0, 1, 2, or 3).

3.2.2. Predictive Factors of Deep Molecular Responses (MR4.5 and MR4.5 Sustained for at Least 24 Months)

Predictive factors of MR4.5: By univariate analysis, female gender (p = 0.0097), B3A2 vs. B2A2 (p = 0.0056), low vs. intermediate Sokal (p = 0.01), low vs. high Sokal (p < 0.001) risk, low vs. intermediate ELTS (p < 0.001), low vs. high ELTS (p < 0.001) risk, were statistically significantly associated with a higher MR4.5 cumulative incidence whereas only a trend was observed for patients without ACA vs. others (p = 0.065). Frontline TKI type was not statistically significant (p = 0.22).

In the final multivariate analysis model, the following were associated with a higher cumulative incidence rate: female gender (SHR ± 95% CI: 1.44 ± 0.27, p = 0.008), B3A2 vs. B2A2 (SHR ± 95% CI: 1.50 ± 0.29, p = 0.006), low vs. intermediate ELTS risk (SHR ± 95% CI: 2.28 ± 0.32, p < 0.001), low vs. high ELTS risk (SHR ± 95% CI: 2.91 ± 0.48, p < 0.001). We observed similar results with the Sokal risk score in the final multivariate analysis model.

Predictive factors of sustained MR4.5 for at least 24 months: The same variables as for MR4.5 were analyzed to identify predictive factors of sustained MR4.5 of at least 24 months. Univariate analysis showed that the female gender (p = 0.021), low vs. intermediate Sokal (p = 0.016), low vs. high Sokal (p < 0.001) risk, low vs. intermediate ELTS (p < 0.001), and low vs. high ELTS (p = 0.003) risk, were statistically associated with a higher sustained MR4.5 cumulative incidence (Table 2). We observed only a trend for B3A2 vs. B2A2 BCR-ABL1 transcript type (p = 0.082). The cumulative incidence of sustained MR4.5 for at least 24 months according to TKI first-line (IMA vs. 2–3G TKI) is presented in Figure 2B. No statistically significant difference between the two TKI treatment groups was demonstrated (p = 0.96). At the onset of sustained MR4.5 for at least 24 months, the majority of patients were still receiving the first-line TKIs (76.6% and 85.1% for IMA and 2–3G TKI, respectively). Only 6.6% of patients treated with IMA frontline had switched to 2–3G TKI for failure or suboptimal response according to the 2013 ELN definitions [26]. In multivariate analyses, the following factors retained statistical significance: female gender (SHR ± 95% CI: 1.40 ± 0.30, p = 0.028), low vs. intermediate ELTS risk (SHR ± 95% CI: 2.18 ± 0.37, p < 0.001), low vs. high ELTS risk (SHR ± 95% CI: 2.10 ± 0.50, p = 0.004). In the multivariate model where ELTS was replaced by Sokal risk score, similar results were observed. Finally, we identified three potential baseline risk factors for the occurrence of sustained MR4.5 for at least 24 months: female gender, B3A2 BCR-ABL1 transcript type, and low ELTS (or Sokal) risk score. The cumulative incidence of sustained MR4.5 for at least 24 months reached 85% in female patients with a B3A2 BCR-ABL1 transcript type and a low ELTS risk score. In contrast, the cumulative incidence observed in male patients harboring a non B3A2 BCR-ABL1 transcript type and an intermediate or high ELTS risk score was only 30%. The cumulative incidence of sustained MR4.5 of at least 24 months in patients presenting with either none, one, two, or three of the latter potential risk factors are presented in Figure 2C.

Table 2.

Predictive factors of sustained MR4.5 for at least 24 months by univariate and multivariate Gray’s test and Fine and Gray Model Analyses.

| Cumulative Incidence of Sustained MR4.5 beyond 24 Months (n = 398) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||||

| Variable | No. Patients | SHR | 95%CI | p | SHR | 95%CI | p |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 230 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Female | 168 | 1.41 | 1.12–1.70 | 0.021 | 1.4 | 1.10–1.70 | 0.028 |

| Age at diagnosis (years old) | 398 | 0.99 | 0.9816–0.9984 | 0.24 | |||

| Type of transcript | |||||||

| B2A2 | 130 | - | - | - | |||

| B3A2 | 209 | 1.33 | 1.02–1.64 | 0.082 | |||

| B3A2 +B2A2 | 23 | 1.11 | 0.46–1.76 | 0.75 | |||

| E8A2 | 1 | 0 | −3.96 | <0.001 | |||

| E19A2 | 2 | 0 | −2.82 | <0.001 | |||

| ACA | |||||||

| No | 368 | - | - | - | |||

| Yes | 30 | 0.74 | 0.13–1.35 | 0.32 | |||

| Sokal | |||||||

| Low | 112 | - | - | - | |||

| Intermediate | 193 | 0.67 | 0.36–0.98 | 0.016 | |||

| High | 76 | 0.46 | 0.01–0.91 | <0.001 | |||

| ELTS | |||||||

| Low | 199 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Intermediate | 122 | 0.46 | 0.089–0.83 | <0.001 | 0.46 | 0.09–0.83 | <0.001 |

| High | 53 | 0.47 | −1.02 | 0.003 | 0.48 | −1.01 | 0.004 |

| TKI first-line | |||||||

| IMA | 291 | - | - | - | |||

| 2–3G TKI | 107 | 0.99 | 0.66–1.32 | 0.96 | |||

Abbreviations: ACA, Additional Cytogenetic Abnormalities; ELTS, EUTOS Long-Term Survival; IMA, Imatinib; 2–3G TKI, 2nd and 3rd Generation Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors.

3.2.3. Proportion of Patients Who Stopped TKI and Molecular Relapse-Free Survival

Among the 182 patients who achieved a sustained MR4.5 at least 24 months, 84 (46%) patients have TKI discontinuation for efficacy with a TFR objective. Eleven additional patients discontinued TKIs for efficacy, six after obtaining an MR4.5 sustained less than 24 months and five without a prior sustained MR4.5. Most patients (75%) who stopped TKI were followed in a university hospital.

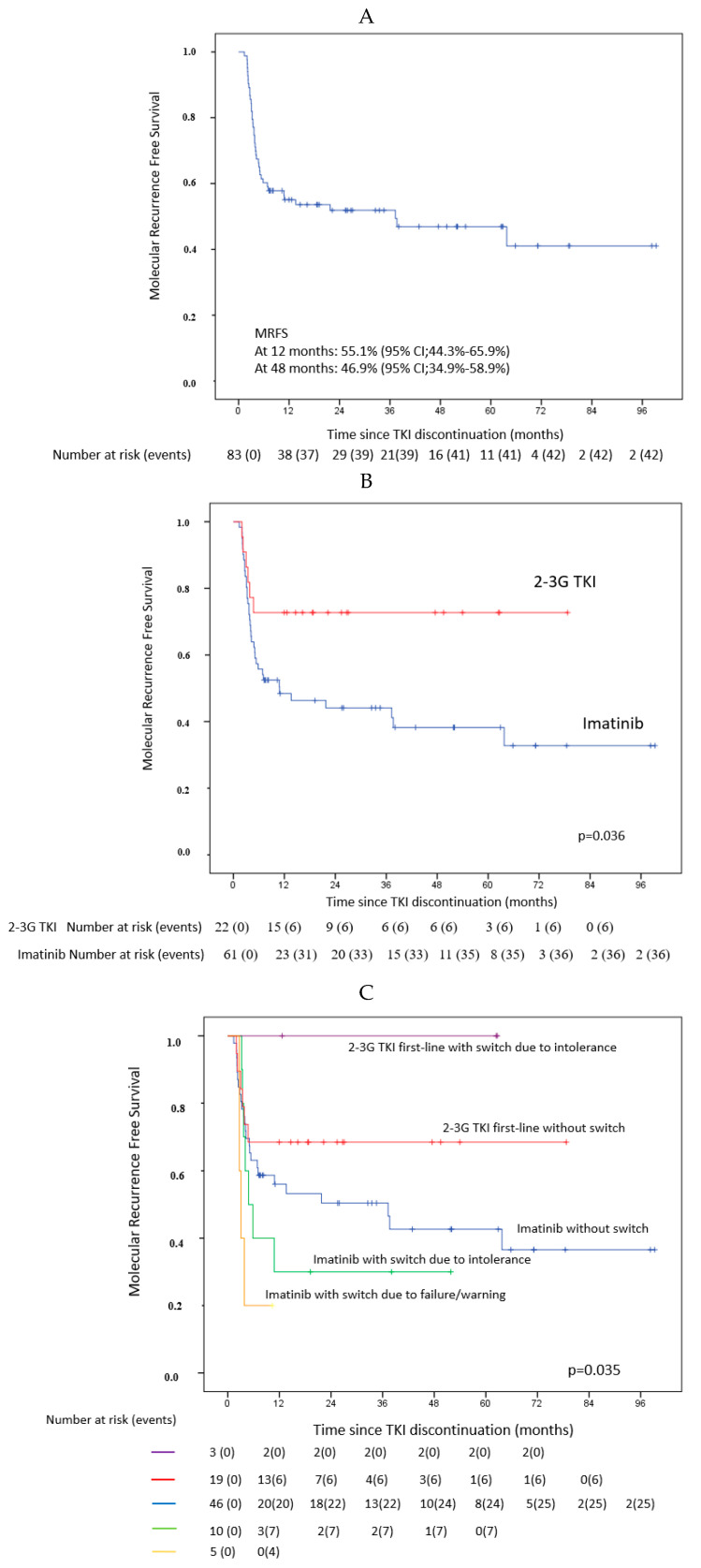

Thus, 95/398 (24%) patients have TKI discontinuation for efficacy. Among these 95 patients, 83 patients were included in the TFR analyses. Twelve patients, with a follow-up lower than 6 months after TKI discontinuation were excluded from the TFR analyses. The baseline and ongoing characteristics of the 83 patients are presented in Table 3. Among them, 42/83 patients had molecular relapse consisting of MMR loss in 36 patients and BCR-ABL1IS increase of at least 1 log with sustained MMR in six patients. MRFS rates at 12 and 48 months were 55.1% (95% CI, 44.3% to 65.9%) and 46.9% (95% CI, 34.9 to 58.9%), respectively (Figure 3A).

Table 3.

Baseline and ongoing characteristics of the treatment-free remission population (N = 83) pts).

| Characteristics | All Patients (N = 83) | With MolRec (N = 42) | Without MolRec (N = 41) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at diagnosis, years (range) | 61.8 (19.2–85.6) |

61.31 (19.2–85.6) |

62.69 (27.6–81.7) |

0.318 |

| Gender, female, n pts (%) | 46 (55.4) | 21 (50) | 25 (61) | 0.216 |

| Sokal risk score, n pts (%) | 0.982 | |||

| Low | 20 (24.1) | 11 (26) | 9 (22) | |

| Intermediate | 40 (48.2) | 21 (50) | 19 (46) | |

| High | 19 (22.9) | 10 (24) | 9 (22) | |

| Unknown | 4 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 4 (9.8) | |

| ELTS risk score, n pts (%) | 0.774 | |||

| Low | 46 (55.4) | 26 (62) | 20 (49) | |

| Intermediate | 19 (22.9) | 9 (21) | 10 (24) | |

| High | 12 (14.5) | 6 (14) | 6 (15) | |

| Unknown | 6 (7.2) | 1 (2) | 5 (12) | |

| Type of Transcript | 0.346 | |||

| Transcript B2A2, n pts (%) | 28 (33.7) | 17 (41) | 11 (27) | |

| Transcript B3A2, n pts (%) | 45 (54.2) | 20 (48) | 25 (61) | |

| Transcripts B3A2 + B2A2, n pts (%) | 3 (3.6) | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.4) | |

| M BCR-ABL1 Nos, n pts (%) | 7 (8.4) | 3 (7.1) | 4 (9.8) | |

| University Hospital, n pts (%) | 65 (78.3) | 30 (71.4) | 35 (85.4) | 0.101 |

| First-line TKI | 0.010 | |||

| IMA, n pts (%) | 61 (73.5) | 36 (85.7) | 25 (60.98) | |

| 2–3G TKI, n pts (%) | 22 (26.5) | 6 (14) | 16 (39) | |

| Median time from TKI start to onset of sustained MR4.5 at least 24 months, months (range) * | 21.5 (2.6–88) |

21.21 (2.6–67.4) |

21.85 (5.3–88) |

0.339 |

| Median time from TKI start to TKI discontinuation, years (range) | 5.77 (2.8–11.2) |

5.13 (2.8–10.6) |

6.46 (3–11.2) |

0.014 |

| Still on first-line TKI at the date of discontinuation, n pts (%) | 64 (77.1) | 31 (73.8) | 34 (82.9) | 0.230 |

| Sustained MR4.5 at least 24 months at the time of TKI discontinuation, n pts (%) | 74 (89.2) | 37 (88.1) | 37 (90.2) | 0.516 |

| Median MR4.5 duration at the time of TKI discontinuation, months (range) | 41.4 (13.1–113.4) |

38.4 (20–104.4) |

62.69 (27.6–81.7) |

0.038 |

Abbreviations: ELTS, EUTOS Long-Term Survival; IMA, Imatinib; 2–3G TKI, 2nd or 3rd Generation Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor; Nos, Not Otherwise Specified; War, warning; Fail, Failure according to the 2013 ELN recommendations18; MolRec, Molecular Recurrence. * Among patients with MR4.5 sustained >24 months.

Figure 3.

Molecular Recurrence-free survival (MRFS) (N = 83 pts). (A): all patients, (B): according to first-line TKI (Imatinib vs. 2nd or 3rd generation TKI), (C): according to first-line TKIs (Imatinib vs. 2nd or 3rd generation TKI) and history of switch for intolerance or insufficient efficacy (failure or warning as defined in the 2013 ELN recommendations [26]).

Among the 83 patients included in the TFR analyses, 61 (73.5%) patients received first-line IMA, and 22 (26.5%) first-line 2–3G TKIs. At the time of TKI discontinuation 15 patients treated with first-line IMA had switched to 2–3G TKIs (10 for intolerance to IMA and 5 because of warning or failure) with a median time on IMA of 7.4 months (range, 1.4 to 99.3 months) and 3/22 patients treated with first-line 2–3G TKI had switched to another 2–3G TKI (intolerance to first-line 2–3G TKI in 3). Among the patients who had a previous switch, eight patients had BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase mutation analyses (using Next Generation Sequencing). Among them, five patients had a previous history of warning or failure and three patients had TKI switch due to intolerance without MMR at the time of switch. None of these patients harbored a BCR-ABL1 domain tyrosine kinase mutation. The median follow-ups from the date of TKI discontinuation to the date of last visit for patients with or without molecular relapse were 26.0 months (range: 11.9 to 78.7) and 34.6 months (range: 7.3 to 99.2), respectively. Three patients died of CML-unrelated causes (cirrhosis, n = 1; myocardial infarction, n = 1; infectious disease, n = 1). All patients died after molecular relapse and TKI resumption.

By univariate analysis, among the patients’ baseline and ongoing characteristics analyzed to identify predictive factors of MRFS, first-line TKI (2–3G TKI vs. IMA), was statistically significantly associated with a better MRFS and a trend was observed for TKI duration and MR4.5 duration.

We performed 2 different multivariate analyses adjusted either on TKI duration or on MR4.5 duration. Considering that some patients receiving first-line IMA had switched to 2–3G TKI in case of intolerance or lack of efficacy, we included in multivariate analysis the history of a switch before TKI discontinuation (Table 4, additional Table 5). The duration of TKI treatment and frontline 2–3G TKIs were the most significant factors. Patients with frontline 2–3G TKI whether or not they had switched, had near three times less risk of molecular relapse than those treated with IMA frontline (HR: 0.36; 95%CI: 0.15 to 0.85; p = 0.027) (Table 4, Figure 3B). MRFS according to frontline TKIs and previous switch to other TKIs are presented in Figure 3C. If we take into account patients with MMR loss only as a definition of molecular relapse, the same results were observed (data not shown).

Table 4.

Predictive factors of molecular recurrence after tyrosine kinase inhibitors discontinuation by univariate and multivariate Cox regression model analyses.

| Cumulative Incidence of MolRec over Time (n = 83) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||||

| Variable | No Patients | SHR | 95%CI | p | SHR | 95%CI | p |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 37 | - | - | ||||

| Female | 46 | 0.7 | 0.38–1.28 | 0.249 | |||

| Age at diagnosis (years old) | 83 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.00 | 0.229 | |||

| Type of transcript | |||||||

| B2A2 | 28 | - | - | ||||

| B3A2 | 45 | 0.6 | 0.31–1.15 | 0.123 | |||

| B3A2 +B2A2 | 3 | 0.88 | 0.20–3.83 | 0.866 | |||

| ACA | |||||||

| No | 79 | - | - | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 0.37 | 0.05–2.69 | 0.326 | |||

| Sokal | |||||||

| Low | 20 | - | - | ||||

| Intermediate | 40 | 0.94 | 0.45–1.95 | 0.867 | |||

| High | 19 | 0.95 | 0.40–2.24 | 0.908 | |||

| ELTS | |||||||

| Low | 46 | - | - | ||||

| Intermediate | 19 | 1.07 | 0.50–2.29 | 0.867 | |||

| High | 12 | 0.81 | 0.33–1.97 | 0.64 | |||

| First-line TKI | |||||||

| IMA | 61 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2–3G TKI | 22 | 0.41 | 0.17–0.97 | 0.043 | 0.36 | 0.15–0.87 | 0.023 |

| TKI switch | |||||||

| No | 65 | - | - | ||||

| Yes | 18 | 1.48 | 0.74–2.97 | 0.266 | 1.4 | 0.70–2.81 | 0.344 |

| TKI duration (years) | 83 | 0.87 | 0.75–1.01 | 0.066 | 0.85 | 0.73–0.98 | 0.029 |

| Time to sustained MR4.5 at least 24 months (months) | 78 | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.467 | |||

| MR4.5 duration (months) | 78 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.00 | 0.095 | |||

Table 5.

Supplemental. Predictive factors of molecular recurrence after tyrosine kinase inhibitors discontinuation by multivariate Cox regression model analyses.

| Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No Patients | SHR | 95%CI | p |

| TKI | ||||

| IMA | 61 | - | - | |

| 2–3G TKI | 22 | 0.42 | 0.17–1.00 | 0.05 |

| Switch | ||||

| No | 65 | - | - | |

| Yes | 18 | 0.92 | 0.41–2.05 | 0.838 |

| MR4.5 duration (months) | 78 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.00 | 0.095 |

4. Discussion

With a median follow-up of seven years, the 10-year estimated OS and PFS observed in the study cohort were 81% and 79%, respectively. These results are similar to the findings reported in previous clinical trials evaluating IMA alone or IMA-based regimens in de novo CP-CML patients [3,4]. As expected and due to the age of our study population, the rate of CML-unrelated death (83% in this study) is higher than that reported in younger CML patient cohorts. Conversely, the incidences of progression events and AHSCT in the first chronic phase—which may prevent progression to late phases of the disease in several patients—were less frequent in our patient’s population than others despite a similar proportion of high Sokal and ELTS risk scores. These differences may be explained in part by the recruitment period (2006 to 2015) with the access to 2nd and 3rd generation TKIs (as frontline treatment or in the case of intolerance or resistance to IMA). Overall, 250 (62.8%) patients had obtained an MR4.5. Among them, 188 (75%) patients were still on first-line TKIs whereas 25% had switched to another TKI before achieving MR4.5 because of TKI intolerance rather than an unsatisfactory response. In the group of the 68 patients who did not achieve sustained MR4.5 for at least 24 months, approximately half of them had a follow-up between the onset of MR4.5 and the last BCR-ABL1/ABL1 available assessment below 24 months. These patients will probably achieve a further stable MR4.5 as the median delay to obtain sustained MR4.5 is 30 months in our cohort.

Provided that only 27% of the patients included in this study were treated with 2–3G TKIs, the cumulative incidence of MR4.5 is comparable to the rates in patients with available molecular assessment from the IRIS trial and the CML-Study IV [3,31]. As sustained MR4.5 were recorded whatever the TKI at the time of the onset of MR4.5 together with a longer follow-up may explain the higher cumulative incidence of stable MR4.5 in this study compared to previous evaluation reported by Branford et al. seven years ago [18].

Several characteristics were associated with a higher probability of achieving an MR4.5 and sustained MR4.5 of at least 24 months. As previously reported, the female gender, B3A2 BCR-ABL1 transcript type, and low-risk scores were associated with a higher probability of MR4.5 [18,32,33,34]. Surprisingly, first-line 2–3G TKI (vs. IMA) was not associated with a higher probability of achieving a sustained MR4.5. Several explanations may be suggested. On the one hand, 28% of the 291 patients treated with first-line IMA had switched to 2–3G TKI before achieving MR4.5 leading to a higher rate of DMR as previously reported [35,36]. On the other hand, patients receiving first-line 2–3G TKI were significantly younger than those receiving first-line IMA treatment (53 years vs. 63 years, p < 0.001). Taking into account that CML phenotype at diagnosis is more aggressive in children and young adults than in older patients [37,38], and that CML genotype including BCR-ABL1 transcript type and somatic variants may also differ with a higher incidence of B2A2 transcript and some (un)known genetic variants in young patients [34,39,40,41]. These differences may be accountable for higher rates of IMA failures and lower rates of DMR observed in the young adult populations than the older population [32,42]. This negative impact of young age on the disease course seems to be reduced with first-line 2nd generation TKIs [42,43,44]. Finally, we believe that the absence of a significant difference in terms of cumulative incidence of DMR between IMA and 2–3G TKI first-line observed in this study is related to the fact that younger patients were preferentially treated with 2–3G TKIs and older patients with first-line IMA.

One of the objectives of this study was to evaluate the proportion of CP-CML patients treated with frontline TKIs eligible for TFR. Among the 398 patients included in this study, 250 (62.8%) patients have achieved an MR4.5, and 182 (46%) a sustained MR4.5 of at least 24 months. Among these 182 patients, 72 patients had a TKI duration below five years and or a prior history of failure or warning according to the 2013 ELN recommendations [26]. Finally, 110/398 (28%) patients fulfilled the criteria for TFR proposed by the French Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia Study Group (Fi-LMC) [13]. Approximately half of the patients who achieved a sustained MR4.5 had entered in a TFR phase. Most patients included in a TFR phase were treated in a university hospital illustrating that TFR evaluation was first performed inside clinical discontinuation trials available only in university hospitals and started later in non-university centers as soon as TFR study results and or recommendations were available.

MRFS at 12 and 48 months after TKI discontinuation were estimated at 55.1% (95% CI, 44.3% to 65.9%) and 46.9% (95% CI, 34.9 to 58.9%), respectively. As no patient resumed TKI without molecular relapse and no death was observed in patients without molecular relapse, the probabilities of TFR and MRFS do not differ.

Although both studies are not comparable, MRFS observed in our study appeared to be lower than the one reported in the previous year by Fava et al. [45]. We hypothesize that baseline characteristics of the populations with a higher proportion of low-risk Sokal score (59% vs. 24%) and a longer TKI duration before stop (7.2 vs. 5.7 years) may account for these differences.

Interestingly, in multivariate analysis first-line TKIs (IMA vs. 2–3G TKIs) in addition to TKI duration were the most predictive factors of MRFS regardless of the definition of molecular recurrence leading to TKI resumption. Whether BCR-ABL1 dependent or independent mechanisms reported to be associated with leukemic stem cells’ persistence leading to molecular relapse after TKI discontinuation are differently impacted by TKIs remains to be determined. However, our results suggest that frontline 2–3G TKIs compared to IMA induce more frequent durable DMR after TKI discontinuation.

In this study, we have analyzed the cumulative incidence of DMR and MRFS after TKI stop taking into account the frontline TKI type and compared IMA vs. other available TKIs inside or outside clinical trials. This comparison remains debatable. However, distinct randomized frontline clinical trials have compared 2nd (nilotinib, dasatinib, bosutinib) and 3rd (ponatinib) generation TKIs to IMA [22,23,24,46]. Except for ponatinib and to a lesser extent bosutinib, 2nd generation TKIs lead to significant sustained higher rates of MMR, MR4, and MR4.5 when compared to IMA [23,24]. Currently, as no head to head comparison between 2nd generation TKI has been done in the frontline setting, we hypothesized that the incidences of DMR would not significantly differ between 2nd and 3rd generation TKIs. In addition, discontinuation of 2nd generation TKIs as front-line or after IMA lead to similar rates of molecular recurrence-free remission [11,47,48,49,50,51].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, whatever the type of frontline TKI, nearly 30% of CP-CML patients receiving first-line TKIs would be optimal candidates for TFR. Due to the different choices of first-line TKI mainly based on a patient’s age at diagnosis, first-line 2–3G TKIs and IMA lead to the same rates of DMR. However, when patients entered into a TFR phase, our results suggested that TKI duration and treatment by first-line 2–3G TKIs were both associated with higher MRFS.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fanny Robbesyn, Marie-Pierre Fort, and Carole Faberes for monitoring the clinical data.

Author Contributions

G.E., C.F., S.D., and F.-X.M. co-designed the study and interpreted the results; G.E., C.F., M.-P.F., L.V., and S.D. collected data and wrote the manuscript; C.F., S.D., and S.K. performed statistical analyses; S.D., F.R., B.T., and E.K. performed molecular analyses; G.E., F.B. (Frederic Bauduer), D.A., F.L., C.L., A.S., S.M., F.B. (Fontanet Bijou), C.D., M.M., F.D., L.V., A.L., and F.-X.M. took care of patients. All authors critically reviewed and approved the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest for the current work. G.E. is a consultant for Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Incyte Pharma and has given some lectures for Bristol Myers Squibb, Incyte Pharma, Pfizer, and Novartis. He has received research grants from Novartis and Bristol Myers Squibb. S.D. has given some lectures for Novartis and Incyte Pharma. F.-X.M. is a consultant for Novartis and Bristol Myers Squibb and has given some lectures for Bristol Myers Squibb, Incyte Pharma, Novartis, and Pfizer. He holds a research grant from Novartis. F.B. (Frederic Bauduer), D.A., F.L., C.D., C.L., A.S., E.K., S.M., M.-P.F., F.B. (Fontanet Bijou), M.M., B.T., F.R., F.D., C.F., L.V., S.K., and A.L. have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Gambacorti-Passerini C., Antolini L., Mahon F.X., Guilhot F., Deininger M., Fava C., Nagler A., Della Casa C.M., Morra E., Abruzzese E., et al. Multicenter independent assessment of outcomes in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with imatinib. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011;103:553–561. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bower H., Bjorkholm M., Dickman P.W., Hoglund M., Lambert P.C., Andersson T.M. Life Expectancy of Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Approaches the Life Expectancy of the General Population. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:2851–2857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hochhaus A., Larson R.A., Guilhot F., Radich J.P., Branford S., Hughes T.P., Baccarani M., Deininger M.W., Cervantes F., Fujihara S., et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Imatinib Treatment for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:917–927. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hehlmann R., Lauseker M., Saussele S., Pfirrmann M., Krause S., Kolb H.J., Neubauer A., Hossfeld D.K., Nerl C., Gratwohl A., et al. Assessment of imatinib as first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: 10-year survival results of the randomized CML study IV and impact of non-CML determinants. Leukemia. 2017;31:2398–2406. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dulucq S., Astrugue C., Etienne G., Mahon F.X., Benard A. Risk of molecular recurrence after tyrosine kinase inhibitor discontinuation in chronic myeloid leukaemia patients: A systematic review of literature with a meta-analysis of studies over the last ten years. Br. J. Haematol. 2020;189:452–468. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortes J., Rea D., Lipton J.H. Treatment-free remission with first- and second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am. J. Hematol. 2019;94:346–357. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rousselot P., Charbonnier A., Cony-Makhoul P., Agape P., Nicolini F.E., Varet B., Gardembas M., Etienne G., Rea D., Roy L., et al. Loss of major molecular response as a trigger for restarting tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in patients with chronic-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia who have stopped imatinib after durable undetectable disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:424–430. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S.E., Choi S.Y., Song H.Y., Kim S.H., Choi M.Y., Park J.S., Kim H.J., Kim S.H., Zang D.Y., Oh S., et al. Imatinib withdrawal syndrome and longer duration of imatinib have a close association with a lower molecular relapse after treatment discontinuation: The KID study. Haematologica. 2016;101:717–723. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.139899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Etienne G., Guilhot J., Rea D., Rigal-Huguet F., Nicolini F., Charbonnier A., Guerci-Bresler A., Legros L., Varet B., Gardembas M., et al. Long-Term Follow-up of the French Stop Imatinib (STIM1) Study in Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:298–305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rea D., Nicolini F.E., Tulliez M., Guilhot F., Guilhot J., Guerci-Bresler A., Gardembas M., Coiteux V., Guillerm G., Legros L., et al. Discontinuation of dasatinib or nilotinib in chronic myeloid leukemia: Interim analysis of the STOP 2G-TKI study. Blood. 2017;129:846–854. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-742205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagafuji K., Matsumura I., Shimose T., Kawaguchi T., Kuroda J., Nakamae H., Miyamoto T., Kadowaki N., Ishikawa J., Imamura Y., et al. Cessation of nilotinib in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia who have maintained deep molecular responses for 2 years: A multicenter phase 2 trial, stop nilotinib (NILSt) Int. J. Hematol. 2019;110:675–682. doi: 10.1007/s12185-019-02736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes T.P., Ross D.M. Moving treatment-free remission into mainstream clinical practice in CML. Blood. 2016;128:17–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-694265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rea D., Ame S., Berger M., Cayuela J.M., Charbonnier A., Coiteux V., Cony-Makhoul P., Dubruille V., Dulucq S., Etienne G., et al. Discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia: Recommendations for clinical practice from the French Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Study Group. Cancer. 2018;124:2956–2963. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochhaus A., Baccarani M., Silver R.T., Schiffer C., Apperley J.F., Cervantes F., Clark R.E., Cortes J.E., Deininger M.W., Guilhot F., et al. European LeukemiaNet 2020 recommendations for treating chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2020;34:966–984. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0776-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saussele S., Richter J., Guilhot J., Gruber F.X., Hjorth-Hansen H., Almeida A., Janssen J.J.W.M., Mayer J., Koskenvesa P., Panayiotidis P., et al. Discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in chronic myeloid leukaemia (EURO-SKI): A prespecified interim analysis of a prospective, multicentre, non-randomised, trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:747–757. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30192-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark R.E., Polydoros F., Apperley J.F., Milojkovic D., Pocock C., Smith G., Byrne J.L., de Lavallade H., O’Brien S.G., Coffrey T., et al. De-escalation of tyrosine kinase inhibitor dose in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia with stable major molecular response (DESTINY): An interim analysis of a non-randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:e310–e316. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark R.E., Polydoros F., Apperley J.F., Milojkovic D., Rothwell K., Pocock C., Byrne J., de Lavallade H., Osborne W., Robinson L., et al. De-escalation of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy before complete treatment discontinuation in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia (DESTINY): A non-randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6:e375–e383. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Branford S., Yeung D.T., Ross D.M., Prime J.A., Field C.R., Altamura H.K., Yeoman A.L., Georgievski J., Jamison B.A., Phillis S., et al. Early molecular response and female sex strongly predict stable undetectable BCR-ABL1, the criteria for imatinib discontinuation in patients with CML. Blood. 2013;121:3818–3824. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-462291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrero D., Cerrano M., Crisa E., Aguzzi C., Giai V., Boccadoro M. How many patients can proceed from chronic myeloid leukaemia diagnosis to deep molecular response and long-lasting imatinib discontinuation? A real life experience. Br. J. Haematol. 2017;176:669–671. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kantarjian H., Shah N.P., Hochhaus A., Cortes J., Shah S., Ayala M., Moiraghi B., Shen Z., Mayer J., Pasquini R., et al. Dasatinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:2260–2270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saglio G., Kim D.W., Issaragrisil S., le Coutre P., Etienne G., Lobo C., Pasquini R., Clark R.E., Hochhaus A., Hughes T.P., et al. Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:2251–2259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cortes J.E., Gambacorti-Passerini C., Deininger M.W., Mauro M.J., Chuah C., Kim D.W., Dyagil I., Glushko N., Milojkovic D., le Coutre P., et al. Bosutinib versus Imatinib for Newly Diagnosed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Results from the Randomized BFORE Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36:231–237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cortes J.E., Saglio G., Kantarjian H.M., Baccarani M., Mayer J., Boqué C., Shah N.P., Chuah C., Casanova L., Bradley-Garelik B., et al. Final 5-Year Study Results of DASISION: The Dasatinib versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naive Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:2333–2340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hochhaus A., Saglio G., Hughes T.P., Larson R.A., Kim D.W., Issaragrisil S., le Coutre P.D., Etienne G., Dorlhiac-Llacer P.E., Clatk R.E., et al. Long-term benefits and risks of frontline nilotinib vs. imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: 5-year update of the randomized ENESTnd trial. Leukemia. 2016;30:1044–1055. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guilhot J., Baccarani M., Clark R.E., Cervantes F., Guilhot F., Hochhaus A., Kulikov S., Mayer J., Petzer A.L., Rosti G., et al. Definitions, methodological and statistical issues for phase 3 clinical trials in chronic myeloid leukemia: A proposal by the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2012;119:5963–5971. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-383711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baccarani M., Deininger M.W., Rosti G., Hochhaus A., Soverini S., Apperley J.F., Cervantes F., Clark R.E., Cortes J.E., Guilhot F., et al. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. Blood. 2013;122:872–884. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-501569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sokal J.E., Cox E.B., Baccarani M., Tura S., Gomez G.A., Robertson J.E., Tso C.Y., Braun T.J., Clarkson B.D., Cervantes F., et al. Prognostic discrimination in “good-risk” chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1984;63:789–799. doi: 10.1182/blood.V63.4.789.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfirrmann M., Baccarani M., Saussele S., Guilhot J., Cervantes F., Ossenkoppele G., Hoffmann V.S., Castagnetti F., Hasford J., Hehlmann R., et al. Prognosis of long-term survival considering disease-specific death in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30:48–56. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cross N.C., White H.E., Muller M.C., Saglio G., Hochhaus A. Standardized definitions of molecular response in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2012;26:2172–2175. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cross N.C., White H.E., Colomer D., Ehrencrona H., Foroni L., Gottardi E., Lange T., Lion T., Machova Polakova K., Dulucq S., et al. Laboratory recommendations for scoring deep molecular responses following treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2015;29:999–1003. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hehlmann R., Muller M.C., Lauseker M., Hanfstein B., Fabarius A., Schreiber A., Proetel U., Pletsch N., Pfirrmann M., Haferlach C., et al. Deep molecular response is reached by the majority of patients treated with imatinib, predicts survival, and is achieved more quickly by optimized high-dose imatinib: Results from the randomized CML-study IV. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:415–423. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.9020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castagnetti F., Di R.F., De V.A., Spilateri A., Gugliotta G., Fabbiano F., Capodanno I., Mannina D., Salvucci M., Antolino A., et al. A population-based study of chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with imatinib in first line. Am. J. Hematol. 2017;92:82–87. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanfstein B., Lauseker M., Hehlmann R., Saussele S., Erben P., Dietz C., Fabarius A., Proetel U., Schnittger S., Haferlach C., et al. Distinct characteristics of e13a2 versus e14a2 BCR-ABL1 driven chronic myeloid leukemia under first-line therapy with imatinib. Haematologica. 2014;99:1441–1447. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.096537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jain P., Kantarjian H., Patel K.P., Gonzalez G.N., Luthra R., Kanagal Shamanna R., Sasaki K., Jabbour E., Romo C.G., Kadia T.M., et al. Impact of BCR-ABL transcript type on outcome in patients with chronic-phase CML treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Blood. 2016;127:1269–1275. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-10-674242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hughes T.P., Lipton J.H., Spector N., Cervantes F., Pasquini R., Clementino N.C.D., Dorlhiac LLacer P.E., Schwarer A.P., Mahon F.X., Rea D., et al. Deep molecular responses achieved in patients with CML-CP who are switched to nilotinib after long-term imatinib. Blood. 2014;124:729–736. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-544015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes T.P., Leber B., Cervantes F., Spector N., Pasquini R., Clementino N.C.D., Schwarer A.P., Dorlhiac-Llacer P.E., Mahon F.X., Rea D., et al. Sustained deep molecular responses in patients switched to nilotinib due to persistent BCR-ABL1 on imatinib: Final ENESTcmr randomized trial results. Leukemia. 2017;31:2529–2531. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castagnetti F., Gugliotta G., Baccarani M., Breccia M., Specchia G., Levato L., Abruzzese E., Rossi G., Iurlo A., Martino B., et al. Differences among young adults, adults and elderly chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Ann. Oncol. 2015;26:185–192. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hijiya N., Schultz K.R., Metzler M., Millot F., Suttorp M. Pediatric chronic myeloid leukemia is a unique disease that requires a different approach. Blood. 2016;127:392–399. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-648667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baccarani M., Castagnetti F., Gugliotta G., Rosti G., Soverini S., Albeer A., Pfirrmann M., International BCR-ABL Study Group The proportion of different BCR-ABL1 transcript types in chronic myeloid leukemia. An international overview. Leukemia. 2019;33:1173–1183. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castagnetti F., Gugliotta G., Breccia M., Iurlo A., Levato L., Albano F., Vigneri P., Abruzzese E., Rossi G., Rupoli S., et al. The BCR-ABL1 transcript type influences response and outcome in Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated frontline with imatinib. Am. J. Hematol. 2017;92:797–805. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ernst T., Busch M., Rinke J., Ernst J., Haferlach C., Beck J.F., Hochhaus A., Gruhn B. Frequent ASXL1 mutations in children and young adults with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2018;32:2046–2049. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pemmaraju N., Kantarjian H., Shan J., Jabbour E., Quintas-Cardama A., Verstovsek S., Ravandi F., Wierda W., O’Brien S., Cortes J. Analysis of outcomes in adolescents and young adults with chronic myelogenous leukemia treated with upfront tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Haematologica. 2012;97:1029–1035. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.056721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giles F.J., Rea D., Rosti G., Cross N.C.P., Steegmann J.L., Griskevicius L., le Coutre P., Coriu D., Petrov L., Ossenkoppele G.J., et al. Impact of age on efficacy and toxicity of nilotinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: ENEST1st subanalysis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2017;143:1585–1596. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2402-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nteliopoulos G., Bazeos A., Claudiani S., Gerrard G., Curry E., Szydlo R., Alikian M., Foong H.E., Nikolakopoulou Z., Loaiza S., et al. Somatic variants in epigenetic modifiers can predict failure of response to imatinib but not to second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Haematologica. 2019;104:2400–2409. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.200220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fava C., Rege-Cambrin G., Dogliotti I., Cerrano M., Berchialla P., Dragani M., Rosti G., Castagnetti F., Gugliotta G., Martino B., et al. Observational study of chronic myeloid leukemia Italian patients who discontinued tyrosine kinase inhibitors in clinical practice. Haematologica. 2019;104:1589–1596. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.205054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lipton J.H., Chuah C., Guerci-Bresler A., Rosti G., Simpson D., Assouline S., Etienne G., Nicolini F.E., le Coutre P., Clark R.E., et al. Ponatinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukaemia: An international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:612–621. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hochhaus A., Masszi T., Giles F.J., Radich J.P., Ross D.M., Gomez Casares M.T., Hellmann A., Stentoft J., Conneally E., Garcia-Gutiérrez V., et al. Treatment-free remission following frontline nilotinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: Results from the ENESTfreedom study. Leukemia. 2017;31:1525–1531. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahon F.X., Boquimpani C., Kim D.W., Benyamini N., Clementino N.C.D., Shuvaev V., Ailawadhi S., Lipton J.H., Turkina A.G., De Paz R., et al. Treatment-Free Remission after Second-Line Nilotinib Treatment in Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in Chronic Phase: Results from a Single-Group, Phase 2, Open-Label Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018;168:461–470. doi: 10.7326/M17-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumagai T., Nakaseko C., Nishiwaki K., Yoshida C., Ohashi K., Takezako N., Takaho H., Kouzai Y., Murase T., Matsue K., et al. Dasatinib cessation after deep molecular response exceeding 2 years and natural killer cell transition during dasatinib consolidation. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:182–192. doi: 10.1111/cas.13430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kimura S., Imagawa J., Murai K., Hino M., Kitawaki T., Okada M., Tanaka H., Shindo M., Kumagai T., Ikezoe T., et al. Treatment-free remission after first-line dasatinib discontinuation in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia (first-line DADI trial): A single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e218–e225. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shah N.P., Garcia-Gutierrez V., Jimenez-Velasco A., Larson S., Saussele S., Rea D., Mahon F.X., Levy M.Y., Gomez-Casares M.T., Pane F., et al. Dasatinib discontinuation in patients with chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia and stable deep molecular response: The DASFREE study. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2020;61:650–659. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2019.1675879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]