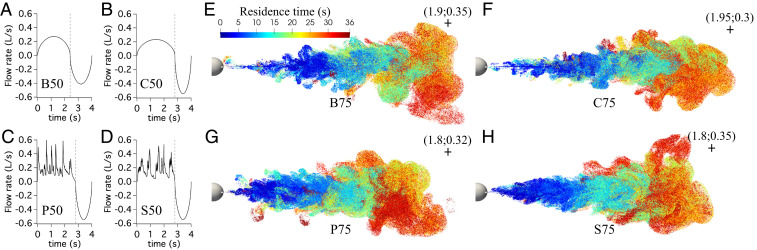

Fig. 4.

Numerical simulations of periodic breathing versus speaking signals for cycles of 4.0 s. The jets issue from a sphere with an open elliptic orifice of semiaxes 1.0 and 1.5 cm. (A–D) volumetric flow rate signals for cases with 0.5 L per breath (hence the “50” in the labels), where the vertical dashed lines mark the separation between exhalation and inhalation. (A) Case B50 is a breathing-like signal with 2.4 s exhalation and 1.6 s inhalation. (C) Case P50 and (D) case S50 are speaking signals sampled from ref. 25 and recorded during articulation of “Peter Piper picked a peck” and “Sing a song of six pence,” respectively, with speaking time of 2.8 s and a 1.2-s inhalation. The P50 and S50 signals have been adjusted to 0.5 L per breath. (B) Case C50 is a calm signal of the same macroscopic characteristics as P50 and S50, but with a smooth signal similar to B50. Three series of simulations have been performed at different volumes per breath, i.e., 0.5, 0.75, and 1.0 L per breath. For the simulation of “Peter Piper picked a peck” for instance, the simulations at 0.75 and 1.0 L per breath are referred to as P75 and P100 and are obtained by multiplying the input flow rate signal of P50 by 1.5 and 2.0, respectively. (E–H) Examples of jets obtained for cases B75, C75, P75, and S75 after nine cycles (36 s), as visualized by perfect tracers issued from the mouth and color coded by their residence time in the computational domain (dark blue tracers were exhaled during the last cycle). The scale is the same for all plots. For each case, a point marked by a “+” is positioned to indicate the axial and radial extent of the jet. The and coordinates of the point are reported as () in E–H. The sphere representing the head is shown to the left in E–H.