Abstract

Cortical neural networks maintain autonomous electrical activity called spontaneous activity that represents the brain’s dynamic internal state even in the absence of sensory stimuli. The spatio-temporal complexity of spontaneous activity is strongly related to perceptual, learning, and cognitive brain functions; multi-fractal analysis can be utilized to evaluate the complexity of spontaneous activity. Recent studies have shown that the deterministic dynamic behavior of spontaneous activity especially reflects the topological neural network characteristics and changes of neural network structures. However, it remains unclear whether multi-fractal analysis, recently widely utilized for neural activity, is effective for detecting the complexity of the deterministic dynamic process. To verify this point, we focused on the log-normal distribution of excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) to evaluate the multi-fractality of spontaneous activity in a spiking neural network with a log-normal distribution of EPSPs. We found that the spiking activities exhibited multi-fractal characteristics. Moreover, to investigate the presence of a deterministic process in the spiking activity, we conducted a surrogate data analysis against the time-series of spiking activity. The results showed that the spontaneous spiking activity included the deterministic dynamic behavior. Overall, the combination of multi-fractal analysis and surrogate data analysis can detect deterministic complex neural activity. The multi-fractal analysis of neural activity used in this study could be widely utilized for brain modeling and evaluation methods for signals obtained by neuroimaging modalities.

Keywords: Complexity, Fluctuation, Log-normal distribution, Spiking neural network, Spontaneous activity

Introduction

Over the past decades, various types of neural activity with complex spatio-temporal patterns have been observed through studies utilizing neuroimaging modalities as well as those utilizing neural network models with high physiological neural characteristics (reviewed in Rabinovich et al. 2006; Garrett et al. 2011; Buzsáki and Mizuseki 2014; Yang and Tsai 2013; Takahashi 2013; Teramae et al. 2012; Kim and Lim 2017, 2018; Oprea et al. 2020). Among these neural activities, cortical neural networks maintain autonomous electrical activity, also termed spontaneous activity or ongoing activity, that represents the brain’s dynamic internal state even in the absence of sensory stimuli (McCormick 1999). Many studies have focused on various hierarchical levels of spontaneous neural activity, from the neuronal level measured by multi-electrode arrays to the neural population level measured by electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), to elucidate their characteristics and functions (McCormick 1999; Fox and Raichle 2007; Garrett et al. 2011; Brookes et al. 2011; Hahn et al. 2017).

At the neuronal level, neural activity exhibits four major characteristics when measured by multi-electrode arrays: irregular neural spiking among almost all neurons, high coherent spike transmission between specific neurons, low firing rate ( Hz), and high coherence between excitatory and inhibitory neural activities (Sakata and Harris 2009). To describe these characteristics, several model-based studies have been conducted over the last decade (Destexhe 2009; Vogels and Abbott 2005; Guo and Li 2010; Teramae et al. 2012). Destexhe reported that the spiking activity in low-threshold spike neurons may induce the appearance of this spontaneous activity (Destexhe 2009). In another study, spontaneous activity was generated by neural network structures such as the small-world property (Guo and Li 2010), sparse random connections (Vogels and Abbott 2005), and log-normal distribution of excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) (Teramae et al. 2012). Especially, the characteristics of spontaneous activity in the models proposed by Teramae et al. (2012) and Vogels and Abbott (2005) are congruent with the actual spiking activity with high physiological validity. Moreover, our model-based study showed that the dual complex cortical network structure, which comprises a small-world network with large EPSPs and a random network with small EPSPs, induces complex neural activity, including slow-temporal behavior; this behavior is congruent with temporal-scale dependencies of cortical neural activity (Nobukawa et al. 2019c).

At the level of brain activity, spontaneous activity is produced by multiple coupling strengths with varied distributions, heavy tails, and feedback loops within and across multiple brain regions; their fluctuations are generally measured by EEG/MEG and fMRI (Teramae et al. 2012; Stam 2005). Many recent studies support the idea that spatio-temporal fluctuations in brain activity play a vital role in the mechanism of cognitive function, aging, and psychiatric disorders (Garrett et al. 2011; Yang and Tsai 2013; Takahashi 2013; Zhang et al. 2016; Nobukawa et al. 2019a). For example, Garrett et al. reported that temporal deviations of blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signals are negatively correlated with age and positively correlated with cognitive function (Garrett et al. 2011). Furthermore, Zhang et al. suggested that spatio-temporal fluctuations in the synchronization of BOLD signals reflect specific brain functions, and are disturbed in psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Zhang et al. 2016). Additionally, we have previously demonstrated that fluctuations in phase synchronization reflect the mechanism of aging, utilizing a method with instantaneous frequency estimated by Hilbert transform in EEG signals (Nobukawa et al. 2019a).

Entropy-based indices and chaos/fractal-based indices have been widely utilized to evaluate the fluctuation of spontaneous activity (Kantz and Schreiber 2004; Yang and Tsai 2013; Takahashi 2013). The neural activities characterized by the power and phase of neural oscillations have different functions in each physiologically relevant, specific temporal-scale range (e.g., perception is associated with the power of the -band, and memory with the phase of the band) (Klimesch et al. 2007). Therefore, indices that can measure the temporal-scale profile of complexity are appropriate for evaluating neural activity. In particular, entropy-based analysis, which is a multi-scale entropy analysis evaluating the degree of dynamic complexity across a range of temporal-scales, has revealed the temporal-scale profiles of complexity in healthy brain functions, development, aging, and several psychiatric disorders (Mizuno et al. 2010; Takahashi et al. 2010; Okazaki et al. 2015; Takahashi et al. 2016; Hasegawa et al. 2018; Nobukawa et al. 2019a; Nobukawa et al. 2020). In addition to the studies with neuroimaging modalities, model-based studies, such as our recent studies with a spiking neural network, have revealed the relationships between network topology and the temporal scale profile of multi-scale entropy (Nobukawa et al. 2018b; Nobukawa et al. 2019c). In chaos/fractal-based indices, Adeli et al. proposed the maximum Lyapunov exponent and correlation dimension in band-specific EEG signals divided by wavelet transformation and revealed disease-specific changes of complexity for Alzheimer’s disease in , , and bands (Adeli et al. 2008). Adeli et al. (2005b, 2005a) and we (Nobukawa et al. 2019d) have also proposed other methods for band-specific fractal dimensions and elucidated disease-specific complexity changes. In addition to these studies with mono-fractal analyses, a multi-fractal analysis with a singularity spectrum is also an appropriate method for evaluating the temporal dependency of complexity; multi-fractal analysis can reveal the time-dependent dynamic behavior of neural activity in brain functions and psychiatric disorders (Van de Ville et al. 2010; Easwaramoorthy and Uthayakumar 2010; Uthayakumar and Easwaramoorthy 2013; La Rocca et al. 2018; Maksimenko et al. 2018).

As described above, the complexity of fluctuations in spontaneous activity is strongly related to brain functions. Moreover, our recent studies have shown that the deterministic dynamic behavior of spontaneous activity especially reflects topological neural network characteristics and the changes of neural network structures caused by aging and development (Hasegawa et al. 2018; Nobukawa et al. 2018b; Nobukawa et al. 2019a, c). However, it remains unclear whether multi-fractal analysis, recently widely utilized for neural activity, can effectively detect the complexity of the deterministic dynamic process; therefore, this study aimed to verify this point. Focusing on multi-fractal analysis, we evaluated whether multi-fractal analysis can detect the deterministic process of the aforementioned temporal fluctuations that are generated by the log-normal distribution of EPSPs as the spiking neural network involving the deterministic dynamic process. We previously reported that the spontaneous spiking activity in the spiking neural network with a log-normal distribution of EPSPs (Teramae et al. 2012) exhibited multi-fractality because of high time-dependent behaviors (Nobukawa et al. 2018a). In this study, against the time-series of neural activity (Nobukawa et al. 2018a), we investigated the existence of deterministic processes in the spontaneous spiking activity by surrogate analysis. First, we evaluated the fluctuation of neural activity in the spiking neural network with a log-normal distribution of EPSPs by multi-fractal analysis. Second, the characteristics of the fluctuations measured by multi-fractal analysis were compared between the original time-series and surrogate data.

Materials and methods

Spiking neural network

To measure the neural activity, a time-series of spike counts per a unit time was utilized. This time-series corresponds to the neural activity at neural population levels typically measured by EEG/MEG (Teplan 2002; da Silva 2013). To produce the spontaneous spiking activity, we utilized a spiking neural network with a log-normal distribution of EPSPs, as modeled by Teramae et al. (2012). The conductance, which is based on a leaky integrate-and-fire neuronal model to describe the membrane potential v(t) in the neural network, is defined as follows:

| 1 |

| 2 |

where, is the membrane decay constant; and , , and represent the reversal potentials of the AMPA receptor-mediated excitatory synaptic current, inhibitory synaptic current, and leak current, respectively. indicates an external input given by mV, where input time estimated from the Poisson process with input rate Hz, and is set to 21 to induce a spike from the resting state. To describe the dynamics of conductance, the excitatory synaptic conductance ms and inhibitory synaptic conductance ms are given by

| 3 |

where, is the decay constant of the excitatory and inhibitory synaptic conductances. , , , and represent the spike time of the synaptic input from the j-th neuron, synaptic delays, and synaptic weights of excitatory synapses, and synaptic weights of inhibitory synapses, respectively. For simulation, we used the following parameter set: mV, mV, mV, mV, mV, ms (excitatory neuron), ms (inhibitory neuron), and ms. To solve Eqs. (1)–(3), Euler’s method with a time step of ms was used. The refractory period was set to 1 ms. In excitatory-to-excitatory and other connections, the synaptic delays were set to uniform random values between 1–3 ms and 0–2 ms, respectively. The sizes of the excitatory and inhibitory neural populations were and , respectively. Each neuron was randomly connected with coupling probabilities, i.e., the probabilities for excitatory and inhibitory connections were 0.1 and 0.5, respectively. In the spiking neural network simulation, Brian2 (https://brian2.readthedocs.io/en/2.0rc/index.html) was utilized (Goodman et al. 2014).

The amplitudes of the excitatory post-synaptic potential mV, which is defined as an increasing membrane potential from resting state induced by an excitatory synaptic input, were produced from a log-normal distribution given by:

| 4 |

where, and the mode of the distribution were set. To remove unrealistic values of , mV were declined, and a new value was re-drawn from the distribution. Here, the observable value of must be translated into synaptic weight . For this translation, we considered the case of a post-synaptic neuron receiving a spike input from a single excitatory synapse at ms. The dynamics of the membrane potential v(t) in this condition can be given by

| 5 |

| 6 |

By solving Eqs. (5) and (6) numerically, the relationship between and can be introduced by . We used the constant values of 0.018 (synaptic weights for excitatory-to-inhibitory), 0.002 (inhibitory-to-excitatory), and 0.0025 (inhibitory-to-inhibitory) as the other synaptic weights. In the excitatory-to-excitatory synaptic connections, the synaptic transmissions failed according to the failing rate with a dependency on the EPSP amplitude: ( mV) (Teramae et al. 2012).

Evaluation methods

Method to observe neural activity

To quantify neural activity, the number of spikes per unit time in the excitatory neural population Hz and inhibitory neural population Hz (called spiking rate in this study) were utilized as follows:

| 7 |

where, and represent the number of spikes in excitatory and inhibitory neural populations at each time step, respectively. In this study, and were smoothed by a Gaussian-shaped window with a width of 10 ms. Gaussian-shaped windows are widely utilized for smoothing time-series of spiking activity (Tetko and Villa 2001; Nobukawa et al. 2019c) to prevent the emergence of spurious high frequency components.

Multi-fractal analysis

Wavelet leaders, which are derived from the coefficients of the discrete wavelet transform, are widely utilized in multi-fractal analysis (Jaffard et al. 2006; Wendt and Abry 2007). The coefficients of the discrete wavelet transform for the discrete time series of X(t) were given by

| 8 |

where, is the mother wavelet function with a compact time support. One-dimensional wavelet leaders were defined as

| 9 |

where, represent the dyadic intervals with scale and is the time neighborhood (Wendt and Abry 2007).

The singularity spectrum D(h), which is a distribution of fractal dimensions represented by the Hölder exponent, was introduced by these wavelet leaders as follows (Jaffard et al. 2006):

| 10 |

h and q represent the Hölder exponent which indicates signal regularity and moment for scaling exponent , respectively. The scaling exponent is the log-cumulants of the wavelet leader coefficients given by

| 11 |

Here, is the structure function given by , where represents the number of samples of X at the scale . When the Hölder exponent h approaches 1, the shape of time-series becomes close to differentiable; whereas, when the Hölder exponent h approaches zero, the shape of time-series becomes close to discontinuous. When the scaling exponent is a linear function and D(h) converges to specific h, the signal is monofractal; whereas, in the scaling exponent when deviates from linear and D(h) distributes to a wide range of h, the signal is multi-fractal. In this study, we used .

Moreover, to evaluate the complexity of the time series for the spiking rate and its temporal dependency, we used first-() and second-order cumulants () of the singularity spectrum. The multi-fractal analysis was performed with the Wavelet Toolbox in MATLAB (https://jp.mathworks.com/products/wavelet.html).

Surrogate data analysis

To evaluate whether a non-linear deterministic dynamic process was involved in the spiking activity, we used surrogate data generated from the iterative amplitude-adjusted Fourier-transformed (IAAFT) surrogate data analysis (Schreiber and Schmitz 1996) for the spiking rate . The iteration number was set to 20, and 10 IAAFT surrogate datasets were generated by different random seeds per original . Values of the 1st and 2nd cumulants were averaged and compared with those from the original . To compare the cumulants for the original data with those for IAAFT, we used a paired-sample t-test. The number of paired samples was set to 11. Two-tailed levels of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Spontaneous activity

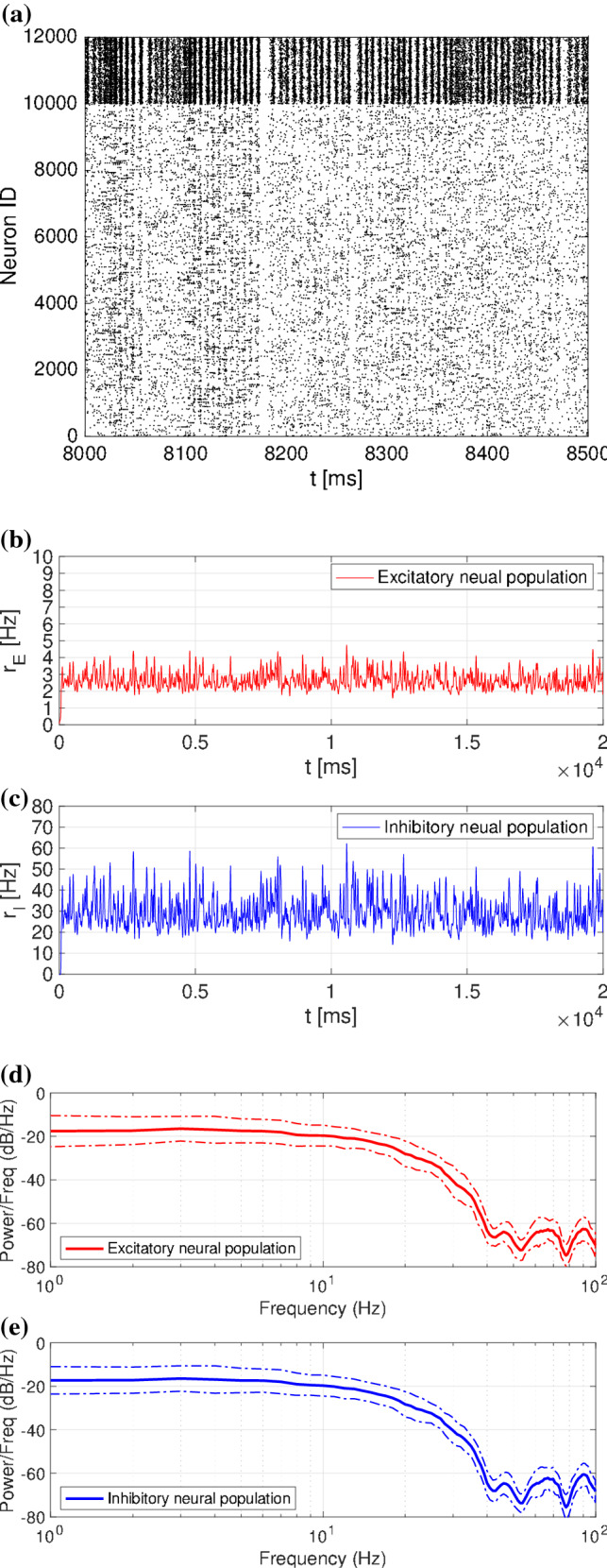

Figure 1 shows the characteristics of the spontaneous spiking activity ( Hz except for the transition period) in a spiking neural network with a log-normal distribution of EPSPs. In the raster plots (see Fig. 1a), spiking activities exhibited high irregularities. As shown in Fig. 1b, the spiking rate in the case of a log-normal distribution of EPSPs had higher variations (excitatory neural population: Hz, inhibitory neural population: Hz). The power spectrum showed that most of the components were distributed in the range of approximately 1–40 Hz (see Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of spiking activities in spiking neural networks with log-normal. a Raster plot. b Time series of spiking rate. c Power spectrum of spiking rate

Multi-fractal analysis and surrogate data analysis

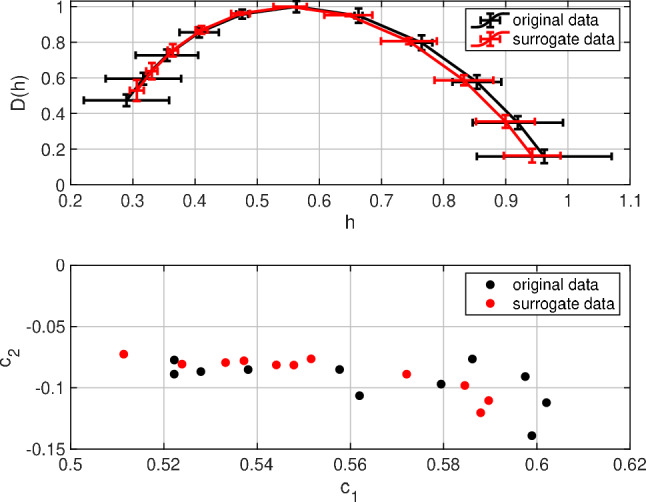

We evaluated the multi-fractal characteristic of neural activity and its non-linear deterministic dynamics. The upper part of the Fig. 2 shows the singularity spectrum D(h) for the original time-series of spiking rate Hz, and the IAAFT surrogate time-series in the spontaneous activity of a spiking neural network with a log-normal distribution of EPSPs. D(h) was distributed in in both time-series, instead of concentrating at specific h. From these results, both time-series involved the multi-fractal characteristic. To compare these distributions of D(h) in more detail, the lower part of the Fig. 2 shows the cumulants of D(h): . Table 1 summarizes the average of the original time series of from 11 trials as well as those for the IAAFT surrogate time series, and their t-values. In both and cases, there were significant differences between the original time series and the time series from the IAAFT surrogate for spontaneous activity. This suggests that multi-fractal analysis can detect the deterministic dynamics of spontaneous activity induced by a log-normal distribution of EPSPs.

Fig. 2.

Multi-fractal analysis for the original time-series of spiking rate Hz and its iterative amplitude-adjusted Fourier-transformed (IAAFT) surrogate time-series in the log-normal and normal distributions for spontaneous. Singularity spectrum D(h) for the time series of spiking rate in the excitatory neural population as a function of the Hölder exponent h (upper parts). The horizontal and vertical error bars indicate standard deviations of h and D(h) from 11 trials, respectively. The 1st and 2nd cumulants of the singularity spectrum ( and ) in 11 trials (lower parts)

Table 1.

The 1st and 2nd cumulants of the singularity spectrum in the original time series of excitatory spiking rate and iterative amplitude-adjusted Fourier-transformed (IAAFT) surrogate time series

| Ave. in original case | Ave. in IAAFT case | t value (p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.563 | 0.553 | () | |

| − 0.095 | − 0.088 | () |

Their t values using the original time series vs. the IAAFT surrogate time series are also shown. Positive t values indicate higher values in the original time series in comparison with the respective value from the IAAFT surrogate time series. Negative values indicate the opposite. The average values were calculated from 11 trials; bold characters indicate a significant difference between the original and surrogate time series

Discussion and conclusions

To confirm whether the multi-fractal analysis is effective in detecting the complexity reflecting the deterministic dynamic process, we evaluated the multi-fractality of spontaneous in spiking neural networks with a log-normal, respectively. The results indicated that the spiking activities exhibited multi-fractal characteristics. Moreover, to investigate the existence of a deterministic process in the spiking activity, we analyzed the IAAFT surrogate against the spiking activities. The result showed that the complexity measured by multi-fractal analysis reflects the deterministic dynamic behavior of spontaneous spiking activity.

Many studies have reported that brain activities acquired by neuroimaging modalities include the deterministic process (Gautama et al. 2003; Nurujjaman et al. 2009; Takahashi 2013; Hasegawa et al. 2018; Nobukawa et al. 2019a). Moreover, these characteristics have been shown to exhibit complex temporal behaviors with temporal dependency (Takahashi 2013; Mizuno et al. 2010; Takahashi et al. 2010; Okazaki et al. 2015; Takahashi 2013; Takahashi et al. 2016; Hasegawa et al. 2018). Similar to the findings of these previous studies, we obtained deterministic complex neural activity with large temporal dependency in neural networks with log-normal distribution of EPSPs. Furthermore, Samura et al. reported that the log-normal distribution of EPSPs is crucial to reproduce the properties of neural activities, such as spike-count rate probabilities and synchrony size (Samura et al. 2015). Our results add to this by providing the characteristics of neural activity produced by log-normal EPSP distributions.

It is worthwhile to discuss the superiority of multi-fractal analysis in the evaluation of neural activity. Generally, the detection of deterministic dynamics is difficult in high dimensional neural systems (Kanamaru 2017; Nobukawa et al. 2019c). Kanamaru constructed a deterministic spiking neural network comprising neurons with chaotic behaviors and evaluated the deterministic process by time-series prediction error (Theiler et al. 1992); consequently, they found that this method cannot specify the deterministic process in the neural activity (Kanamaru 2017). In our previous study, we reported that multi-scale entropy analysis cannot be used to detect the deterministic process of spontaneous activity in a random network (corresponding to the network topology used in this study), except for dual complex network structures (Nobukawa et al. 2019c). However, the multi-fractal analysis used in this study can be used to detect the deterministic process of spontaneous activity. This suggests that multi-fractal analysis may be better able to detect the deterministic neural activity in comparison with other methods of evaluating complexity.

Furthermore, the application of complex neural activity induced by the log-normal distribution of EPSPs must be considered. Recently, the application of spiking neural networks to machine learning has made rapid progress (Lee et al. 2016; Lin et al. 2017; Kulkarni and Rajendran 2018; Kheradpisheh et al. 2018; Lin et al. 2018; Tavanaei et al. 2018b; Mozafari et al. 2018; Tavanaei et al. 2028a; Wu et al. 2018; Nobukawa et al. 2019b). However, these spiking neural networks generally do not exhibit complex dynamic behavior because they possess overly simple network structures and use a simplistic spiking neuron model. Nevertheless, Bellec et al. showed that the neural dynamics and neuro-inspired recurrent structure might enhance learning ability (Bellec et al. 2018). Therefore, the long-tailed distribution of synaptic weight, which can produce complex temporal-scale-dependent dynamics, could be utilized to enhance the ability of machine learning using spiking neural networks. To achieve this, further evaluation of the functionality of neural activity with log-normal characteristics is needed. For efficient implementation of spiking neural networks to solve machine learning problems, modeling with neuro-inspired programs (Bonzon 2017) is one of the major candidates.

The limitations of this study must be considered. The structure of the spiking neural network we used is restricted to local cortical network structures. Consequently, mutual interactions among different brain regions cannot be described. In future studies, a spiking neural network with region-specific sub-networks and inter-regional connections should be constructed to evaluate the relationship between the complexity of neural activity and the connectivity topology of the structural sub-network. Furthermore, spontaneous activity should not be restricted because the evaluation of neural activities under task-related stimuli are important. It is also important to elucidate whether the advantage of multi-fractal analysis for detecting the deterministic process of neural activity is maintained when it is applied to physiological experimental data. For this, the robustness of the method to stochastic noise in experimental conditions and actual neural systems must first be evaluated.

In conclusion, the combination of multi-fractal analysis and surrogate data analysis can detect deterministic complex neural activity. Although several limitations exist, the multi-fractal analysis of neural activity used in this study could be widely utilized for brain modeling and evaluation methods for signals obtained by neuroimaging modalities.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI for Early-Career Scientists Grant Number 18K18124.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adeli H, Ghosh-Dastidar S, Dadmehr N. Alzheimer’s disease and models of computation: imaging, classification, and neural models. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7(3):187–199. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeli H, Ghosh-Dastidar S, Dadmehr N. Alzheimer’s disease: models of computation and analysis of EEGs. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2005;36(3):131–140. doi: 10.1177/155005940503600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeli H, Ghosh-Dastidar S, Dadmehr N. A spatio-temporal wavelet-chaos methodology for eeg-based diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2008;444(2):190–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellec G, Salaj D, Subramoney A, Legenstein R, Maass W (2018) Long short-term memory and learning-to-learn in networks of spiking neurons. In: Advances in neural information processing systems, pp 787–797

- Bonzon P. Towards neuro-inspired symbolic models of cognition: linking neural dynamics to behaviors through asynchronous communications. Cogn Neurodyn. 2017;11(4):327–353. doi: 10.1007/s11571-017-9435-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes MJ, Woolrich M, Luckhoo H, Price D, Hale JR, Stephenson MC, Barnes GR, Smith SM, Morris PG. Investigating the electrophysiological basis of resting state networks using magnetoencephalography. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2011;108(40):16783–16788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112685108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G, Mizuseki K. The log-dynamic brain: how skewed distributions affect network operations. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(4):264–278. doi: 10.1038/nrn3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva FL. EEG and MEG: relevance to neuroscience. Neuron. 2013;80(5):1112–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destexhe A. Self-sustained asynchronous irregular states and up–down states in thalamic, cortical and thalamocortical networks of nonlinear integrate-and-fire neurons. J Comput Neurosci. 2009;27(3):493. doi: 10.1007/s10827-009-0164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easwaramoorthy D, Uthayakumar R (2010) Analysis of biomedical EEG signals using wavelet transforms and multifractal analysis. In: 2010 international conference on communication control and computing technologies, IEEE, pp 544–549

- Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(9):700. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett DD, Kovacevic N, McIntosh AR, Grady CL. The importance of being variable. J Neurosci. 2011;31(12):4496–4503. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5641-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautama T, Mandic DP, Van Hulle MM. Indications of nonlinear structures in brain electrical activity. Phys Rev E. 2003;67(4):046204. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.67.046204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman DF, Stimberg M, Yger P, Brette R. Brian 2: neural simulations on a variety of computational hardware. BMC Neurosci. 2014;15(1):P199. [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Li C. Self-sustained irregular activity in 2-D small-world networks of excitatory and inhibitory neurons. IEEE Trans Neural Netw. 2010;21(6):895–905. doi: 10.1109/TNN.2010.2044419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn G, Ponce-Alvarez A, Monier C, Benvenuti G, Kumar A, Chavane F, Deco G, Frégnac Y. Spontaneous cortical activity is transiently poised close to criticality. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(5):e1005543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa C, Takahashi T, Yoshimura Y, Ikeda T, Saito DN, Kumazaki H, Minabe Y, Kikuchi M. Developmental trajectory of infant brain signal variability: a longitudinal pilot study. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:566. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffard S, Lashermes B, Abry P (2006) Wavelet leaders in multifractal analysis. In: Wavelet analysis and applications, Springer, pp 201–246

- Kanamaru T. Chaotic pattern alternations can reproduce properties of dominance durations in multistable perception. Neural Comput. 2017;29(6):1696–1720. doi: 10.1162/NECO_a_00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantz H, Schreiber T. Nonlinear time series analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kheradpisheh SR, Ganjtabesh M, Thorpe SJ, Masquelier T. STDP-based spiking deep convolutional neural networks for object recognition. Neural Netw. 2018;99:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Lim W. Dynamical responses to external stimuli for both cases of excitatory and inhibitory synchronization in a complex neuronal network. Cogn Neurodyn. 2017;11(5):395–413. doi: 10.1007/s11571-017-9441-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Lim W. Effect of spike-timing-dependent plasticity on stochastic burst synchronization in a scale-free neuronal network. Cogn Neurodyn. 2018;12(3):315–342. doi: 10.1007/s11571-017-9470-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch W, Sauseng P, Hanslmayr S, Gruber W, Freunberger R. Event-related phase reorganization may explain evoked neural dynamics. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31(7):1003–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni SR, Rajendran B. Spiking neural networks for handwritten digit recognition—supervised learning and network optimization. Neural Netw. 2018;103:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rocca D, Zilber N, Abry P, van Wassenhove V, Ciuciu P. Self-similarity and multifractality in human brain activity: a wavelet-based analysis of scale-free brain dynamics. J Neurosci Methods. 2018;309:175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Delbruck T, Pfeiffer M. Training deep spiking neural networks using backpropagation. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:508. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Wang X, Hao Z. Supervised learning in multilayer spiking neural networks with inner products of spike trains. Neurocomputing. 2017;237:59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Ma D, Meng J, Chen L. Relative ordering learning in spiking neural network for pattern recognition. Neurocomputing. 2018;275:94–106. [Google Scholar]

- Maksimenko VA, Pavlov A, Runnova AE, Nedaivozov V, Grubov V, Koronovslii A, Pchelintseva SV, Pitsik E, Pisarchik AN, Hramov AE. Nonlinear analysis of brain activity, associated with motor action and motor imaginary in untrained subjects. Nonlinear Dyn. 2018;91(4):2803–2817. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA. Spontaneous activity: signal or noise? Science. 1999;285(5427):541–543. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5427.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno T, Takahashi T, Cho RY, Kikuchi M, Murata T, Takahashi K, Wada Y. Assessment of EEG dynamical complexity in Alzheimer’s disease using multiscale entropy. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;121(9):1438–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozafari M, Kheradpisheh SR, Masquelier T, Nowzari-Dalini A, Ganjtabesh M. First-spike-based visual categorization using reward-modulated STDP. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2018;29:6178–6190. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2018.2826721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobukawa S, Aiura H, Yoshida H, Nishimura H, Yamanishi T (2018a) Temporal fluctuation in spontaneous activity of a spiking neural network with long-tailed synaptic weights. In: Proceedings of 2018 international symposium on nonlinear theory and its applications (NOLTA 2018), IEICE, pp 375–378

- Nobukawa S, Nishimura H, Yamanishi T (2018b) Skewed and long-tailed distributions of spiking activity in coupled network modules with log-normal synaptic weight distribution. In: International conference on neural information processing, Springer, pp 535–544

- Nobukawa S, Kikuchi M, Takahashi T. Changes in functional connectivity dynamics with aging: a dynamical phase synchronization approach. NeuroImage. 2019;188:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobukawa S, Nishimura H, Yamanishi T. Pattern classification by spiking neural networks combining self-organized and reward-related spike-timing-dependent plasticity. J Artif Intell Soft Comput Res. 2019;9(4):283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Nobukawa S, Nishimura H, Yamanishi T. Temporal-specific complexity of spiking patterns in spontaneous activity induced by a dual complex network structure. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49286-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobukawa S, Yamanishi T, Nishimura H, Wada Y, Kikuchi M, Takahashi T. Atypical temporal-scale-specific fractal changes in Alzheimer’s disease EEG and their relevance to cognitive decline. Cogn Neurodyn. 2019;13(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11571-018-9509-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobukawa S, Yamanishi T, Kasakawa S, Nishimura H, Kikuchi M, Takahashi T. Classification methods based on complexity and synchronization of electroencephalography signals in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:255. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurujjaman M, Narayanan R, Iyengar AS. Comparative study of nonlinear properties of EEG signals of normal persons and epileptic patients. Nonlinear Biomed Phys. 2009;3(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1753-4631-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki R, Takahashi T, Ueno K, Takahashi K, Ishitobi M, Kikuchi M, Higashima M, Wada Y. Changes in EEG complexity with electroconvulsive therapy in a patient with autism spectrum disorders: a multiscale entropy approach. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:106. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oprea L, Pack CC, Khadra A. Machine classification of spatiotemporal patterns: automated parameter search in a rebounding spiking network. Cogn Neurodyn. 2020;14:267–280. doi: 10.1007/s11571-020-09568-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich MI, Varona P, Selverston AI, Abarbanel HD. Dynamical principles in neuroscience. Rev Mod Phys. 2006;78(4):1213. [Google Scholar]

- Sakata S, Harris KD. Laminar structure of spontaneous and sensory-evoked population activity in auditory cortex. Neuron. 2009;64(3):404–418. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samura T, Ikegaya Y, Sato YD. A neural network model of reliably optimized spike transmission. Cogn Neurodyn. 2015;9(3):265–277. doi: 10.1007/s11571-015-9329-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber T, Schmitz A. Improved surrogate data for nonlinearity tests. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77(4):635. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam CJ. Nonlinear dynamical analysis of EEG and MEG: review of an emerging field. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116(10):2266–2301. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T. Complexity of spontaneous brain activity in mental disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;45:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Cho RY, Mizuno T, Kikuchi M, Murata T, Takahashi K, Wada Y. Antipsychotics reverse abnormal EEG complexity in drug-naive schizophrenia: a multiscale entropy analysis. Neuroimage. 2010;51(1):173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Yoshimura Y, Hiraishi H, Hasegawa C, Munesue T, Higashida H, Minabe Y, Kikuchi M. Enhanced brain signal variability in children with autism spectrum disorder during early childhood. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37(3):1038–1050. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavanaei A, Kirby Z, Maida AS (2018a) Training spiking ConvNets by STDP and gradient descent. In: 2018 international joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN), IEEE, pp 1–8

- Tavanaei A, Masquelier T, Maida A. Representation learning using event-based STDP. Neural Netw. 2018;105:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2018.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplan M, et al. Fundamentals of EEG measurement. Meas Sci Rev. 2002;2(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Teramae J, Tsubo Y, Fukai T. Optimal spike-based communication in excitable networks with strong-sparse and weak-dense links. Sci Rep. 2012;2:1–6. doi: 10.1038/srep00485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetko IV, Villa AE. A pattern grouping algorithm for analysis of spatiotemporal patterns in neuronal spike trains. 2. Application to simultaneous single unit recordings. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;105(1):15–24. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00337-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theiler J, Eubank S, Longtin A, Galdrikian B, Doyne Farmer J. Testing for nonlinearity in time series: the method of surrogate data. Physica D. 1992;58:77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Uthayakumar R, Easwaramoorthy D. Epileptic seizure detection in EEG signals using multifractal analysis and wavelet transform. Fractals. 2013;21(02):1350011. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ville D, Britz J, Michel CM. EEG microstate sequences in healthy humans at rest reveal scale-free dynamics. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2010;107(42):18179–18184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007841107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogels TP, Abbott LF. Signal propagation and logic gating in networks of integrate-and-fire neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25(46):10786–10795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3508-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt H, Abry P. Multifractality tests using bootstrapped wavelet leaders. IEEE Trans Signal Process. 2007;55(10):4811–4820. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Deng L, Li G, Zhu J, Shi L. Spatio-temporal backpropagation for training high-performance spiking neural networks. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:331. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang AC, Tsai SJ. Is mental illness complex? From behavior to brain. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;45:253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Cheng W, Liu Z, Zhang K, Lei X, Yao Y, Becker B, Liu Y, Kendrick KM, Lu G, et al. Neural, electrophysiological and anatomical basis of brain-network variability and its characteristic changes in mental disorders. Brain. 2016;139(8):2307–2321. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]