Abstract

Introduction

The literature around use of Large Diameter Heads (LDH) is abundantly available for revision Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA) but is lacking for primary uncomplicated THA. This systematic review was undertaken to synthesize data around primary THA involving LDH and analyze the associated complications (dislocation, volumetric wear, implant survivorship and functional score) along with reported effects on range of motion (ROM), patient reported outcomes and impingement rate/groin pain.

Methods

A PRISMA compliant systematic review was done using extensive search in PubMed database, along with offline search looking for the literature published in English language between 2008 and 2018. The articles providing data on the use of large diameter heads (LDH) (36 mm or larger) on various bearing surfaces were collected. This included robust national joint registries of different countries. Narrative approach to data synthesis was used.

Results

A total of 23 papers met our inclusion criteria, including six national joint registries. It was observed that LDH had significantly low dislocation rates, excellent implant survival rate as per Kaplan–Meier survivorship (> 90% at five years). Surgical approaches, except Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS), did not increase any risk of dislocation as long as it was meticulously repaired. There was no significant improvement in any functional scores or improved ROM.

Conclusions

LDH of 32–36 mm are now commonly used in primary THA and is accepted as a popular size. The beneficial effects of a large head size are negated beyond 38 mm. The most favored size for LDH THA, therefore, is 36 mm contrary to the older literature favoring 28 mm.

Keywords: Total hip arthroplasty, Primary, Adverse effect, Dislocation, Bearing surfaces

Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is one of the most common and widely performed operations throughout the world which aims to relieve pain, restore function and mobility and improve overall quality of life [1]. It is also regarded as a highly successful and reproducible procedure with cost-effective results [2] and with minimal associated complications.

Large Diameter Head (LDH) in THA is reported to have improved range of motion (ROM), greater jump distance, decreased impingement and resultant increased stability [3–5] and the drawbacks being increased rate of wear leading to implant loosening and taper corrosion (trunnionosis), generation of wear particles leading to problems like metallosis and ALVAL (Aseptic Lymphocyte-dominant Vasculitis-Associated Lesions) and reduced implant survivorship due to limitation of using a thick insert. There is also reported higher risk of groin pain in a small number of patients [6] possibly due to iliopsoas impingement.

As the diameter of head increases, the rate of volumetric wear increases (more than linear wear) especially on hard on soft bearing (metal-on-poly) which can be the cause for early failure of THA [7]. However, with the introduction of improved hard-on-hard (ceramic on ceramic, metal on ceramic) bearing surfaces, as well as the development of newer liners such as highly cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE) or Vitamin E supplemented poly ethylene, this has encouraged surgeons to use large femoral heads with thinner acetabular liners in the attempt to reduce dislocations. Currently, there are several studies assessing the wear rate of large femoral heads with XLPE and are recording low wear rates over 5 years and advocate the use of these implants. [8]

The National Joint Registry [9] (NJR) shows a 20% increase in use of heads larger than 36 mm since 2006. However, later annual reports do not reveal any further changes in the usage of large femoral heads. The value of LDH arthroplasty (LDHA) in primary THA is questionable because many studies which demonstrate their contribution in stability in vivo, have no representation in their influence in joint ROM and functional recovery [10]. At this current period, we are not sure if increasing the head size (with other factors considered neutral) is the only solution to address problem of dislocation. On the other hand, this leads to increased volumetric wear rate and a risk of early revisions. We aimed to address this gap in knowledge in our study.

Methodology

A systematic review was performed following the principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and adhering to the strict inclusion criteria.

The primary outcome measures included reported incidences of post-operative dislocations (early or late), volumetric wear rate, revision rate and implant survivorship rate. The secondary outcome measures included functional improvement expressed by improvement in Harris Hip Score (HHS) post operatively, patient reported outcome measures (PROMs), post-operative range of motion (ROM) improvement and miscellaneous outcomes such as reported impingement or groin pain, liner fracture, ALVAL and ARMD (Adverse Reaction to Metal Debris).

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The population of interest for our study purpose were adult human subjects (age > 18 years) who have undergone primary THA, not complicated by any pre-existing anatomic, structural or metabolic abnormalities (osteoporosis, storage disorders, tumours) which affect the bone quality. All studies using head diameter 36 mm or more, irrespective of the type, were included in the study.

We considered only papers pertaining to primary arthroplasty and excluded those done for congenital hip conditions such as Developmental Dysplasia of Hip (DDH), Achondroplasia, dwarfism or gigantism. We also excluded surgeries done in high risk patients for dislocation. We excluded studies done on dual mobility cups and constrained liners to make the study population homogeneous and generalizable.

We included all publications in English language between 2008 and 2018 with all relevant patient data and a follow-up period of minimum one year. We excluded animal or laboratory studies showing effects in a simulated setting because of the inherent clinical limitations. We excluded abstracts and letters to editors. Case reports and case series comprising of less than twenty-five hips were excluded (Appendix 2).

Search Strategy

The comprehensively searched database engine was PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov./en-trez/query.fcgi) and literature search was done on two separate occasions (Nov. and Dec. 2018). Searches were restricted to English language, published in the last 10 years. A detailed search strategy with used MeSH terms are shown in Appendix 1. A search of unpublished and grey literature search was also done using electronic database SIGLE. Google scholar, expert opinion and web search were considered to be unpublished literature.

Study Selection

We identified and generated a list of titles and abstracts for the relevant articles. Full paper was retrieved if decision could not be made from the abstracts. We utilized the method of ‘reference checking’ to gain access to grey literature as well as to avoid any relevant study which would have been missed by electronic database search. We also cross-checked references, citations in review papers.

Titles and abstracts were screened by two authors independently with the agreed and defined inclusion criteria. A full article was then extracted for the each of the potentially eligible study and printed. Each full text paper was allocated a unique number for record keeping and easy identification in the subsequent stages (e.g. Record no 1, 2 and so on). Any eligible study with insufficient data/information or not accessible by internet, the authors were contacted by email in the correspondence address provided requesting for the required information. If the author did not respond till data extraction stage or if data were irrelevant to our study, we excluded such study.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

All included articles were weighed on their quality and all of them had received appropriate ethical clearance from their respective institutional boards before publication. None of them had any conflicts of interest and had been declared on publication.

All of these studies assessed same intervention (i.e. femur head size 36 mm or larger) but were not stratified according to bearing surfaces, surgical approaches, age or gender. So, the total cohort is a mix of variable bearing surfaces, cemented or uncemented fixation, done for various indications.

The reported lost to follow-up or dead patients have been excluded from the total number reported. The outcomes of our interest (primary and secondary) have been extracted from a list of many outcomes available and has been presented in tabulated form and text. The studies that did not include quantitative results in text, we read through the graphical or tabulated forms provided in figures/tables. For any data inconsistent with our analysis, we attempted to calculate the data required for our study, failure to do so, we excluded them from analysis.

Quality Assessment of Included Studies

The Newcastle–Ottawa scale was used to assess the methodological quality of each study (Appendix 4). It was carried out for each included study by each reviewer and any disagreements resolved by third reviewer.

Results of Screening

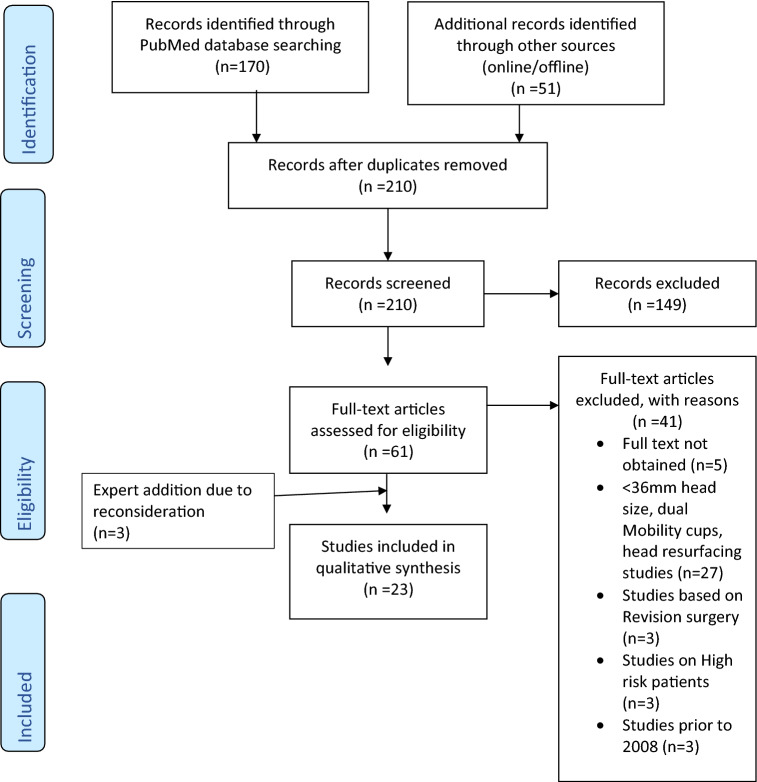

Total of 23 papers were selected after extensive search and subjected to quality assessment, which was done prior to data extraction to avoid selection bias. The flow diagram (Fig. 1) depicts the selection at each stage and the reasons for exclusion.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2009 four phase flow diagram (from https://www.prisma-statement.org)

Unfortunately, there were very few meta-analyses available and were not directly related to this topic. The only available three RCTs relevant to our study were evaluated and two of them were based on revision surgeries that had to be excluded, leaving only one RCT to be included. The nature of heterogenous data and the study characteristics (Appendix 3) obtained due to different follow-up times and periods and with different combination of bearing surfaces, effect measures precluded a meta-analysis.

Results and Discussion

The National Joint Registry of England, Wales and Northern Ireland represented 5% THA in 2005, 26% in 2009 and 35% in 2011 using femoral head size 36 mm and shows increasing trend of LDH being favoured by surgeons to decrease risk of dislocation and increase range of motion. There is corresponding drop in rate of dislocations from 1.12% (2005) to 0.86% (2009) with the use of LDH [11]. Historically, the THA does not favour the use of LDH due to high wear rates especially on hard-on-soft articulations, but there has been rejuvenated interests after introduction of hard-on-hard bearings and especially with the introduction of cross-linked PolyEthylene (XLPE) and Vitamin E supplemented PolyEthylene liners.

Head Size, Dislocation Rate and Surgical Approach

The current literature base establishes the inverse relationship of head size with dislocation, provided implant is placed in acceptable position. Our results strongly support this fact based on long term follow-up studies in joint registry studies and high-volume studies. 9 out of 20 studies reported 0% to < 1% dislocation rate, majority of them being done through the posterior or postero-lateral approach. Three papers report dislocation rate > 1% up to 5%, however, these are small sample size studies. Posterior or postero-lateral approach have equal dislocation risk as other approaches, but Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS) has the highest dislocation risk unrelated to the head size or the approach [20]. The stability benefit provided by increased head size is dependent on cup orientation and is lost in case of mal positioning [12] (cup in abduction).

The overall 6-year rate of revision for dislocation, stratified by surgical approach was 0.5–0.6%. The cause of hip instability being multifactorial, capsular repair, restoration of the offset of the femur and the acetabulum either individually or in combination, maintaining soft tissue balance coupled with large head diameter add to the stability of the hip and thus reduce the incidence of dislocation. At this point in time, we feel that it is difficult to ascertain whether that a large femoral head in isolation reduces the dislocation rate. At best, it adds to the stability of the hip and minimises if not excludes the risk of dislocation.

Head Size: Effect on Bearing Surfaces and Volumetric Wear Rate

Five studies discussed head size correlation against measured volumetric wear. It was found that highest volumetric wear rate occurs in hard-on-soft interface (e.g. MoPE) to insignificant in hard-on-hard interface (e.g. CoC). With larger head size, the larger surface area in contact causes more wear. The causes of increase wear volume with increasing head diameter are related to increased contact distance and speed during movement and to reduced liner thickness. This increases not only wear but also stress within the material, leading to mechanical degradation of the PE resulting in fracture of liner, fatigue failure and delamination of the liner. A minimum thickness of 8 mm is recommended to limit these effects [13]. By increment of 1 mm femoral head diameter, the wear rate increased from 7.5% to 10% in MoPE bearings [14]. Thus, while using large head (36 mm or more), wear-resistant bearings need to be chosen to minimise this problem. Johnson et al. [15] advised to consider the minimum recommended thickness of poly ethylene liner, traditionally which was 6 mm, can be reduced up to 3.9 mm with Ultra High Molecular Weight PE (UHMWPE). The evolution of the newer liners has seen vitamin E supplemented cross-linked PE, however, the current argument for the ‘gold standard’ liner thickness remains to be minimum 6 mm regardless of the type of bearing [16].

Medium to long term risk of revision is lowest in MoPE bearings across worldwide registries and published trials, and no functional benefit of alternative bearings have so far been found [17]. The material used for the articulating surfaces does not appear to influence the risk of revision and metal on polyethylene appears to be safe and acceptable [7, 34, 36].

Head Size and Its Effect on Revision Rate

We observed six studies [18–23] which describe the overall revision rate in larger sample sizes with the risk of revision ranging from 1 to 5%.

Instability was the most common cause for overall revision followed by infection [18–22]. The other causes were aseptic loosening (either stem or cup or both), mal-positioning of implants and peri-prosthetic fractures. We did not find liner fracture, squeaking or impingement to be the reasons for revision. This was in various combinations of the liner surfaces as all the above listed articles are based on large scale population registry studies. The highest reported revision rate (7.5%) is in MoM combination and is due to ARMD complications [23]. The Swedish registry study shows that the risk of revision factors to be associated with small head size [18] (RR = 2.5, CI 1.1–5.7; p = 0.03), female sex, posterior approach and MIS.

The Finnish registry shows revision risk factors to be male sex and higher in the time period 2006–2010 and similar risk with resurfacing arthroplasty for LDH MoM THA [19]. Another Finnish registry study shows LDH MoM THA done in female sex, aged 55 or more had increased risk of revision when compared to cemented THA and the head diameter or diagnosis did not have any statistically significant influence on revision rate [21].

In another registry study done in USA, the risk factors for revision were female sex (1.35 times higher), white race, CoC and CoPE/MoPE interface had higher risk of revision [22]. Lombardi et al. found out that age at surgery (older patients had better outcome), cup inclination (increasing angle has poor survivorship) and female sex were risk factors for component revision and not BMI, diagnosis, activity level, surgical approach, cup or stem type [23]. The Dutch arthroplasty register study shows 36 mm heads have a significantly higher risk of revision (2.7%) (RR = 2.67, CI 2.42–3.00; p < 0.05) for other reasons than dislocation [20].

The available data suggest varying confounding variables contributing to revisions and with little evidence to suggest that larger femoral heads increase the risk of revision. We believe in the coming years with increasing numbers of LDHA and with due consideration for other varied factors, better consistent information will be available.

Head Size and Kaplan–Meier Survivorship

Seven papers, including three registry studies, evaluated implant survivorship. An excellent survivorship (> 95%) was noted mainly in MoM bearing surfaces. Between 90 and 95% survivorship reported in one paper and < 90% in one paper having a long follow-up (87% at 8 years).

With the endpoint of revision for any reason except infection, the implant survival rate was excellent 94.8% (95% CI 90.9–98.8) and for revision due to any reason as end point the survival rate reached excellent 92.7% (95% CI 87.9–97.5) [24]. Hu et al. [25], in Taiwan claim that they achieved 100% implant survival with mean follow-up of 8.4 years, but they have abandoned the use of Durom® cup due to its technical difficulty related to it. They attribute the success to enhanced stability from use of muscle-sparing surgical techniques.

Another study [23] shows 1235 out of 1440 patients having LDH MoM THA implants survived over 12 years which is reasonably good. They report taper junction wear in 40% (18 of 45) and pseudo-tumours in 49% (22 of 45) in revised patients. Khatod report an excellent survival rate of 96.4% at 8 years the end point being revision due to any cause. The recalled ASR® Hip system was found to have an increased risk of failure over time compared to other brands in this study and after 500 days they have greater risk of failure [22].

Head Size and Harris Hip Score (HHS) Improvement

Eleven studies discussed functional outcome based on final HHS. Majority of the studies were small size studies [25–28] and although all of them reported improvement in mean HHS at final follow-up, the results were not statistically significant in comparison to preoperative HHS. Hip function scores are subjective assessments and so are highly variable across studies and necessarily do not reflect the true functionality of the implant. Different scoring systems use different parameters of everyday functions and are generally applicable across large population subsets. The wide variation in the scores are probably due to lack of a uniform system of assessment and the time and method used at the time of recording the findings.

HHS cannot be a reliable predictor of functionality as various other factors affect the true functioning. And many of them were recorded on the basis of telephonic conversation with the patients. These factors which affect the HHS could be due to inaccurate reporting or variable timing (ranging from as early as 6 weeks post-operative till 5 years post-operative period) when these were recorded. The cohort of the patients is not uniform as the implants have variable bearing surfaces although the head size was 36 mm or larger. In few studies, HHS did not depend on the femoral head size [10, 33–35].

In summary we can conclude that HHS is not a reliable secondary outcome indicator of a well-functioning hip and is not directly related to the femoral head diameter in isolation. We recommend using a uniform assessment score at specific post-operative periods (e.g. 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and annual) using objective assessment methods such as pedometer to measure the number of steps cycles the patient takes, and jig to assess range of motions.

Head Size and Improvement in Range of Motion (ROM)

Increased head size improves ROM especially flexion range in reported studies but failed to reach statistical significance. This is in contrast to the results shown in vitro studies where large head size (38 mm or more) have additional 12 degrees of globally improved ROM [29].

Lu [28] reported significantly better improved flexion range when > 36 mm CoC articulation was used. Another study [30] showed improved flexion from mean 95 degrees (range 50–115) to 101 degrees (range 90–120, p < 0.0001) post-operatively. Singh et al. agree that there is improved post-operative ROM with large head size [31] but was not statistically significant. The ROM improvement did not show any statistically significant difference according to head size [10, 33–35].

The methods to assess ROM in all these studies was done by measurement with a goniometer and manual assessment (sometimes visual assessment) which are not very reliable methods and can have clinical discrepancies. We feel that absolute head size is not critical in determining ROM, but the head neck and head cup ratio secondarily influences impingement and ROM.

Head Size and Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs)

Most studies suggest good outcomes of > 90% rating the procedure to be above Good (good, very good, excellent) as reported in five papers. Saragaglia et al., in their single centre-single surgeon study involving 156 hips using LDH MoM THA, reported 90.4% (n = 132) patients were very satisfied or satisfied, 3.4% (n = 5) dissatisfied and the rest unsure [24]. Hu et al., claim all of their patients were satisfied with the procedure with few complications [25] (mal-positioned cup, inadequately seated cups and acetabular fracture). One study compared PROM based on bearing surfaces and head size and found no statistically significant difference among bearing surfaces MoPE, CoPE, CoC (p = 0.05) but patients were clearly more satisfied when using LDH 36 mm or more (p = 0.001) with mean days of PROM completion 210 (range 183–363). Sachde et al., reported good to fair results (96%) on PROM based on pain score improvement, HHS and function [27]. No one required revision surgery due to complications or unimproved scores. These are subjective grading from the patients’ description of their capability, so it is very much possible that it might overestimate or underestimate the true functionality and outcome.

Head Size and Other Effects

Impingement and Thigh Pain

Several studies in our review report thigh pain ranging from 8.6 to 21.5% patients in small scale studies [27, 32, 36] which is comparable with studies by Steven et al. [16] and Berton et al. [32]. The studies however do not specifically attribute the head size as a cause of pain but due to a combination of factors such as implant mal-positioning, early infection and short neck length as possible contributing factors. We agree that impingement can be due to bony cause (resulting from too little neck resection) or implant cause (resulting from excessive neck resection), so it may not be directly dependent on the head size.

There have been reports of unexplained post-operative hip pain and we attribute it to impingement pain due to low head-neck ratio, low neck-cup distance causing cam effect of the oversized implant, but it has not been sufficiently severe to warrant a revision surgery [24, 26, 36].

ALVAL, ARMD & Pseudotumour

We note few studies [23–25] reporting the incidence of ARMD and pseudo-tumour formation in MoM interface which warranted revision surgery. They have also reported metallosis and hypersensitivity reactions. The ALVAL and ARMD effects were very frequent and required component revision or explantation and were clearly one of the causes of revision. This also had poor HHS and poor satisfaction from patient’s perspective as shown in PROMs. Currently, there is a trend in moving away from MoM articulations and we do hope these issues will be eliminated in course of time.

Liner Fracture

We did note one study [22] mentioning component fracture at 1.7% (n = 11) as a cause for revision, but it is not attributed to LDH.

Squeaking or Grinding Noise

In a study [28] in Taiwan, it mentions 0 squeaking and 2.4% noise (grinding) in large head group but not showing a significant association (p = 0.868) and did not warrant any surgical intervention.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

A major strength of our study is the large cohort of patients in registry data which allowed us to compare large number of THAs. The limitations to this study are the observational nature of most of the studies, some missing data and attrition, which could lead to information bias. It was impossible to match populations based on age and sex categories as well as bearing surfaces or fixation modes due to heterogeneity in the available selected studies.

Our review includes many national joint registries that do not record dislocations which were managed by closed reduction (that did not have revision operations or operative interventions). Therefore, it misses those dislocations that were managed by closed reductions under anaesthesia or those not revisable hips due to poor general health. The numbers of such unreported dislocations can be very high, therefore underreporting of these leads to reporting bias in the published literature. Most studies examined revision surgery as an end point for implant survivorship and most do not capture the failed implants which may have not been revised (due to not seeking medical attention or due to poor general health making them unsuitable candidates for surgery).

Due to exclusion of smaller studies (less than 25 cases), it was possible that the results could have been influenced by publication bias by favouring statistically significant results. The studies having relatively short follow-up do not capture unstable hips, and some papers not monitoring PROMs and radiographic assessment for loosening tend to underestimate the magnitude of the dislocation or loosening as well as functional outcome.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The current trend has now reversed back in favor of medium-sized head (i.e. 36 mm) from the practice of using very large diameter heads, with the phasing out of the hip resurfacing type of arthroplasty. Many surgeons prefer ceramic heads with LDH used with XLPE or Vitamin E supplemented PE liner.

The importance of good technical skills for correct placement of implant to provide optimal outcomes cannot be replaced by mere use of LDH. However, the choice of femoral head size has increased over recent years, especially with the availability of improved liner surfaces as evidenced clinically in the joint registries, seems to be a correct decision. But the resurgence of very large diameter heads (> 36 mm) and MoM bearings is not expected due to past failures and bad track record.

Many joint registry studies are not stratified according to fixation modes (cemented/uncemented), prosthesis material and design thus precluding a true representation of the result [18, 19, 22, 23]. Further studies comprising a large population of patients with robust record keeping and follow-up studies are recommended in this area to precisely determine the effect of liner surface, modes of fixation and implant design on the survivorship and functionality. Factors like surgery by trainees, associated co-morbidities, low theatre efficiency and unfamiliar theatre setup may contribute to increased risk of dislocation.

Appendix 1 Search Strategy in PubMed

PubMed advanced search using MeSH terms “arthroplasty, replacement, hip” with Boolean ‘AND’ Mesh subheading “adverse effects” OR “complications/trends” retrieved 7102 results. Further screening of these results for “hip dislocation*/etiology” and “hip dislocation/epidemiology” and “Hip prosthesis/methods” narrowed down search to 5524 results. Refining further with search words and after defining “large diameter” AND Human subjects NOT animal studies AND English literature published in the last 10 years in the search builder.

Appendix 2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| S. No. | Inclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Population |

Any country of study English language Any setting (single/multi-centric) Industry sponsored or non-sponsored Published or unpublished Studies from last 10 years (2008 till 2018) Number of participants (at least 25) Minimum one year follow-up Primary arthroplasty surgery only |

| 2 | Intervention | Large diameter head (36 mm or larger size of prosthetic femur head) (cobalt–chromium, alumina or ceramic) done in primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) |

| 3 | Comparison | Small diameter heads (< 36 mm) |

| 4 | Outcomes |

Primary: post-operative dislocation rates, implant survivorship including (volumetric wear rate), revision rate Secondary: improvement in function measured by Harris Hip Score, improvement in ROM, patient satisfaction level as reported on PROMs and miscellaneous (ALVAL, impingement & groin pain, liner fracture etc.) |

| 5 | Study design | Any (meta-analysis, systematic reviews, RCT, case–control, cohort, case series) |

| Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|

|

Abstracts, letter to editor/author, expert opinion Case reports and case series comprising of less than twenty-five hips Non-human studies Laboratory/experimental studies Revision surgeries Primary arthroplasty done in complications (infection/peri-prosthetic fractures/conversion surgeries) Complex primary surgery (DDH, achondroplasia, dwarfism, gigantism) and done in high risk for dislocation patients (see table for high risk factors) |

Appendix 3 Characteristics of Included Studies

| Author (year) | Head size (mm)/type | Type/level of study | Single/multi centric study | Total no pt (hips) | Male (%) | Female (%) | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu (2012) | Durom LDH | Prospective III/IV | Multi | 59 (70) | 66 | 34 | Taiwan |

| Saragalia (2015) | 38–56 | Retrospective IV | Single | 146(156) | 53 | 47 | France |

| Lu (2015) | ≥ 36 | Retrospective IV | ? | 41 (42) | 51 | 49 | Taiwan |

| Hu (2017) | Durom LDH | Retrospective IV | ? | 80 (96) | 72.5 | 27.5 | Taiwan |

| Howie (2016) | 36 | RCT II | Single | 29 (*) | 52 | 48 | Australia |

| Shah (2017) | 36 | Prospective IV | Multi | (192,275) | NA | NA | Australia |

| Kindsfater (2012) | 36 | Prospective III/IV | Single | (85) | 60 | 40 | USA |

| Jameson (2015) | 36 | Prospective IV | Multi | (1863) | 58 | 42 | UK |

| Zijlstra (2017) | Retrospective IV | Multi | (166,231) | NA | NA | Netherlands | |

| Singh (2013) | 36 | Prospective III/IV | single |

281 (317) |

72.8 | 27.2 | India |

| Mokka (2013) | Retrospective IV | Multi | (25,037) | 54 | 46 | Finland | |

| Delay (2016) | 38–56 | Case control III/IV | Single |

101 (112) |

NA | NA | France |

| Agarwala (2014) | 36–44 | Retrospective IV | Single |

59 (62) |

NA | NA | India |

| Stroh-Alex (2012) | 36, 40 | Case control III/IV | Single |

225 (248) |

60.8 | 39.2 | USA |

| Allen (2014) | ≥ 36 | Prospective III/IV | Single | (327) | 63 | 37 | New Zealand |

| Lachiewicz (2018) | 36–40 | Retrospective IV | single |

93 (107) |

NA | NA | USA |

| Hammerberg (2010) | 38, 44 | Prospective III/IV | ? |

30 (33) |

NA | NA | USA |

| Ho (2012) | 36 | Retrospective IV | ? |

404 (421) |

42 | 58 | UK |

| Lombardi (2015) | ≥ 38 | Retrospective IV | Single |

1235 (1440) |

55 | 45 | USA |

| Khatod (2014) | ≥ 36 | Retrospective IV | Multi | (35,960) | 42.6 | 57.4 | USA |

| Sachde (2012) | 36 | Retrospective IV | Single | 28 | 71 | 29 | India |

| Hailer (2012) | 36 (4%) | Prospective III/IV | Multi | 2722 out of 61,743 pt (78,098) | 40 | 60 | Sweden |

| Kostensalo (2013) | 36, > 36 | Prospective III/IV | Multi | (13,764) | NA | NA | Finland |

| Author (year) | Country type of study | Study period | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion | Final no of pts (hips) | Mean F/U in year (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hailer (2012) | Sweden (SHAR) | 2005 to 2010 | HD 22–36 mm |

Rarely used HD (24, 26, 30, 40) Missing data No info on approach |

61,743 (78,098) | 2.7 (0–6) |

| Khatod (2014) | USA (TJRR) | 2001 to 2010 | < 36, > 36 | Revision, conversion, MoC, CoCPE | (36,834) | 2.9 (1.2–5.1) |

| Zijlstra (2017) | Dutch (LROI) | 2007 to 2015 | All non-MoM primary THA 22 to > 38 | AVN, dysplasia, NOF # | (166,231) | 3.3 (?–9) |

| Shah (2017) | Australian NJR | 1999 to 2014 |

Primary THA, MoXLPE, CoXLPE, CoC 28,32,36 |

THA with LDH MoM | (192,275) | 13 (N/A) |

| Jameson (2015) | NJR for England & Wales | 2008 to 2010 | Primary cementless THA | NOF# | 247,546 | 1.5 (N/A) |

| Kostensalo (2013) |

Finland Finnish Arthroplasty Register |

1996 to 2010 | Primary THA & hip resurfacing, age 18–100, 28, 32, 36, > 36 mm | Operated before 1996, missing data | 42,379 | 4.1 (2.4–7.6) |

| Mokka (2013) |

Finland Register |

2002 to 2009 | Pri & sec OA, cemented LDH THA, MoPE, MoM | Age > 85 years, RA |

(16,978) + (8059) |

4.1 (0–8) 2.4 (0–7.8) |

| Lombardi (2015) | USA | 2001 to 2010 | LDH MoM primary THA ≥ 38 | < 2 year F/U | 1235 (1440) | 7(2–12) |

Appendix 4 Quality Assessment Using Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

| Cohort studies | Representativeness of cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Ascertainment of outcome | Adjustment for confounder | Duration of follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu (2012) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Saragalia (2015) | U | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Lu (2015) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Hu (2017) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Shah (2017) | U | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Kindsfater (2012) | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

| Jameson (2015) | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Zijlstra (2017) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Singh (2013) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Mokka (2013) | Y | U | Y | U | Y |

| Delay (2016) | U | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Agarwala (2014) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Stroh-Alex (2012) | U | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Allen (2014) | U | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Lachiewicz (2018) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hammerberg (2010) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Ho (2012) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Lombardi (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Khatod (2014) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

|

Sachde (2012) |

Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

|

Hailer (2012) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

|

Kostensalo (2013) |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| RCT | Randomization | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Incomplete outcome report | Selective outcome report |

| Howie (2016) | Y | U | Y | Y | Y |

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standard statement

This study (Systematic Review) does not deal with direct participation of patients, but assimilating data of studies done by others who have obtained permission from their respective boards. Hence, ethical approval is not required to do a systematic review. This was confirmed after subjecting the information to Medical Research Council (MRC) Health Research authority.

Informed consent

Not required for this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Noordin S, Lakdawala R, Masri BA. Primary total hip arthroplasty: Staying out of trouble intraoperatively. Annals of Medicine and Surgery (London) 2018;29:30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry DJ, von Knoch M, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS. Effect of femoral head diameter and operative approach on risk of dislocation after primary total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American. 2005;87-A:2456–2463. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartz RL, Nobel PC, Kadakia NR. The effect of femoral component head size on posterior dislocation of the artificial hip joint. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American. 2000;9:1300. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200009000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cross M, Nam D, Mayman D. Ideal femoral head size in total hip arthroplasty balances stability and volumetric wear. HSS Journal Springer-Verlag. 2012;8(3):270–274. doi: 10.1007/s11420-012-9287-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rathi P, Pereira GC, Giordani M. The pros and cons of using larger femoral heads in total hip arthroplasty. American Journal of Orthopedics (Belle Mead NJ) 2013;8:E53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Browne JA, Polga DJ, Sierra RJ, Trousdale RT, Cabanela ME. Failure of larger-diameter metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty resulting from anterior iliopsoas impingement. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2011;26(6):978.e5–978.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lachiewicz PF, Heckman DS, Soileau ES. Femoral head size and wear of highly cross-linked polyethylene at 5 to 8 years. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2009;467(12):3290. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1038-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen C, Hooper G, Frampton C. Do larger femoral heads improve the functional outcome in total hip arthroplasty? The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2014;29:401–404. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Joint Registry for England and Wales (NJR England-Wales): 10th Annual Report 2013. https://www.njrcentre.org.uk. Accessed 16 Dec 2018

- 10.Delay C, Putman S, Dereudre G, Girard J, Lancelier-Bariatinsky V, Drumez E, Migaud H. Is there any range of motion advantage to using bearings larger than 36 mm in primary hip arthroplasty: a case control study comparing 36 mm and large diameter heads. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research. 2016;102:735–740. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jameson SS, Lees D, James P, Serrano-Pedraza I, Partington PF, Muller SD, Meek RM, Reed MR. Lower rates of dislocation with increased femoral head size after primary total hip replacement: a five-year analysis of NHS patients in England. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 2011;93(7):876–880. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B7.26657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crowninshield RD, Maloney WJ, Humphrey SM, Blanchard CR. Biomechanics of large femoral heads. What they do and don’t do. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2004;429:102–107. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000150117.42360.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Triclot P, Gouin F. Update- Big head: the solution to the problem of hip implant dislocation? Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research. 2011;97S:S42–S48. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jasty M, Maloney WJ, Bragdon CR. The initiation of failure in cemented femoral components of hip arthroplasties. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 1991;73:551–558. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B4.2071634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson AJ, Le Duff MJ, Yoon JP, Al-Hamad M, Amstutz HC. Metal ion levels in total hip arthroplasty versus hip resurfacing. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2013;28(7):1235–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girard J. Femoral head diameter considerations for primary total hip arthroplasty. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research. 2015;101:S25–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sedrakyan A, Normand SL, Dabic S. Comparative assessment of implantable hip devices with different bearing surfaces: systematic appraisal of evidence. BMJ. 2011;343:7434. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hailer NP, Garellick G, Karrholm J. Uncemented and cemented primary total hip arthroplasty in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthopedics. 2010;81:34. doi: 10.3109/17453671003685400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kostensalo I, Junnila M, Virolainen P, Remes V, Matilainen M, Vahlberg T, Pulkkinen P, Eskelinen A, Makela KT. Effect of femoral head size on risk of revision for dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: a population-based analysis of 42,379 primary procedures from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthopedics. 2013;84:342–347. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.810518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zijlstra WP, van den Akker-Scheek I, Zee MJ. No clinical difference between large metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty and 28-mm-head total hip arthroplasty? International Orthopaedics. 2011;35(12):1771. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1233-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mokka J, Makela K, Virolainen P, Remes V, Pulkkinen P, Eskelinen A. Cementless total hip arthroplasty with large diameter metal on metal heads: short term survivorship of 8059 hips from the finnish arthroplasty register. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. 2013;102:117–123. doi: 10.1177/1457496913482235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khatod M, Cafri G, Namba RS, Inacio MC, Paxton EW. Risk factors for total hip arthroplasty aseptic revision. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2014;29(7):1412–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lombardi AV, Jr, Berend KR, Morris MJ, Adams JB, Sneller MA. Large-diameter metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: dislocation infrequent but survivorship poor. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2015;473(2):509–520. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3976-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saragaglia D, Belvisi B, Rubens-Duval B, Pailhé R, Rouchy R, Mader R. Clinical and radiological outcomes with the Durom acetabular cup for large-diameter total hip arthroplasty: 177 implants after a mean of 80 months. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research. 2015;101(4):437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu CC, Huang TW, Lin SJ, et al. Surgical approach may influence survival of large-diameter head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: A 6- to 10-year follow-up study. BioMed Research International. 2017;2017(2017):4209634. doi: 10.1155/2017/4209634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu PT, Wang CJ, Yen CY, Jian JS, Lai K. Cementless large-head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 60 years—a multicenter early result. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences. 2012;28(1):30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2011.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sachde B, Maru ND. Mid-term results of large diameter heads on cross-linked polyethylene liners in total hip replacement. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics Trauma. 2012;3(2):94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu YD, Yen SH, Kuo FC, Wang JW, Wang CJ. No benefit on functional outcomes and dislocation rates by increasing head size to 36 mm in ceramic-on-ceramic total hip arthroplasty. Biomedical Journal. 2015;38:538–543. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burroughs BR, Hallstrom B, Golladay GJ. Range of Motion and stability in total hip arthroplasty with 28,32,38,44 mm femoral head sizes. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2005;20:11. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kindsfater KA, Sychterz Terefenko CJ, Gruen TA, Sherman CM. Minimum 5-year results of modular metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2012;27:545–550. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh G, Meyer H, Ruetschi M, Cha-maon K, Feuerstein B, Lohmann CH. Large-diameter metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasties: a page in orthopedic history? Journal of Biomedical Materials Research A. 2013;101:3320–3326. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berton C, Girard J, Krantz N, Migaud H. Early results with a large-diameter metal-on-metal bearing. Journal of Bone Joint Surgery (Br) 2010;92(2):202–208. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B2.22653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammerberg EM, Wan Z, Dastane M, Dorr LD. Wear and range of motion of different femoral head sizes. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2010;25(6):839–843. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stroh A, Issa K, Johnson A, Delanois R, Mont M. Reduced dislocation rates and excellent functional outcomes with large-diameter femoral heads. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1415–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agarwala S, Mohrir G, Moonot P. Functional outcome following a large head total hip arthroplasty: A retrospective analysis of mid-term results. Indian J Orthopaedics. 2014;48:410–414. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.136295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lachiecwicz PF, O’Dell JA, Martell JM. Large metal heads and highly cross-linked polyethylene provide low wear and complications at 5–13 years. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2018;33(7):2187–2191. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]