Abstract

Of all the ESKAPE pathogens, carbapenem-resistant and multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii is the leading cause of hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia. A. baumannii infections are notoriously hard to eradicate due to its propensity to rapidly acquire multitude of resistance determinants and the virulence factor cornucopia elucidated by the bacterium that help it fend off a wide range of adverse conditions imposed upon by host and environment. One such weapon in the arsenal of A. baumannii is the outer membrane protein (OMP) compendium. OMPs in A. baumannii play distinctive roles in facilitating the bacterial acclimatization to antibiotic- and host-induced stresses, albeit following entirely different mechanisms. OMPs are major immunogenic proteins in bacteria conferring bacteria host-fitness advantages including immune evasion, stress tolerance, and resistance to antibiotics and antibacterials. In this review, we summarize the current knowledge of major A. baumannii OMPs and discuss their versatile role in antibiotic resistance and virulence. Specifically, we explore how OmpA, CarO, and OprD-like porins mediate antibiotic and amino acid shuttle and host virulence.

Keywords: OmpA, CARO, OprD, antibiotic resistance, virulence

Introduction

The Gram-negative coccobacillus Acinetobacter baumannii is an aerobic opportunistic pathogen responsible for some of the most morbid hospital-acquired infections (Bouvet and Grimont, 1987; Peleg et al., 2008; Lin and Lan, 2014; Lee et al., 2017). The global threat from this pathogen comes from its high rate of resistance gene acquisition leading to rapid emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) clinical isolates (Abbott et al., 2013; Giammanco et al., 2017; Rodloff and Dowzicky, 2017). Increasing number of studies show frequent isolation of carbapenem and colistin-resistant strains of A. baumannii from clinical settings (Garnacho-Montero et al., 2005; Asadollahi et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2015; Benmahmod et al., 2019; Pormohammad et al., 2020). Swift accumulation and dispersion of antibiotic resistance markers along with the ability to cause urinary tract infections, skin and soft tissue infections and wound infections (Sievert et al., 2013; Weiner et al., 2016; Giammanco et al., 2017) makes A. baumannii, a pathogen of great significance for both humans and animals (Sen and Joshi, 2016; van der Kolk et al., 2019). In light of this, the World Health Organization (WHO) categorized this organism as a priority-1 critical pathogen for which discovery of new treatment options is of utmost importance (World Health Organization [WHO], 2017). The potency of A. baumannii as a successful pathogen can be elaborated by the high number of deaths associated with its infection. A recent finding showed that bacteremia caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) A. baumannii exhibited 56.2% mortality rate among infected patients (Zhou et al., 2019).

A plethora of virulence factors are elucidated by A. baumannii (Harding et al., 2018), some of which include, but are not limited to, porin proteins, efflux pumps, outer membrane vesicles, metal acquisition systems, secretion systems, phospholipases, and capsular polysaccharides (Lee et al., 2017; Sharma et al., 2019; Skariyachan et al., 2019). Recent advances in research have not only provided better knowledge of these determinants, but also shed light on how these can be used as potential drug targets (Bhattacharyya et al., 2017; Iyer et al., 2018). However, growth conditions like temperature, oxygen content, osmolarity, and media components regulate the expression of porins in A. baumannii (Hwa et al., 2010; Fernando and Kumar, 2012; Bazyleu and Kumar, 2014). Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory networks (Kuo et al., 2017; Sharma et al., 2018) also determine the virulence and antibiotic resistance of A. baumannii.

Among the vast diversity of antibiotic resistance and virulence determinants and A. baumannii specific regulatory networks, one group of bacterial proteins, termed outer membrane proteins (OMPs) due to their localization, have been studied with utmost interest due to their distribution, functional relevance and stipulated role in both antibiotic resistance and virulence (Sato et al., 2017; Nie et al., 2020). OMPs in general are beta barrel-shaped monomeric or trimeric porins (Table 1) that allow diffusion of small molecules into and out of periplasmic space of Gram-negative bacteria (Nitzan et al., 1999; Nikaido, 2003; Slusky and Dunbrack, 2013). A. baumannii outer membrane holds scores of OMPs including OmpA, CarO, OprD- like OMPs, Omp 33-36 kDa, AbuO, TolB, DcaP, Oma87/BamA, NmRmpM, CadF, OprF, etc. (Borneleit and Kleber, 1991; Park et al., 2012; Srinivasan et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017; Bhamidimarri et al., 2019; Rasooli et al., 2020). OMPs participate in a wide range of functions that assist the bacterium in enduring the harsh environmental conditions, in combating the threat posed by antimicrobial compounds (Limansky et al., 2002; del Mar Tomás et al., 2005; Dupont et al., 2005; Mussi et al., 2007; Choi et al., 2008a; Srinivasan et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015), host (Choi et al., 2008b,c; Lee et al., 2008; Gaddy, 2010), and surprisingly, in degrading crude oil (Hanson et al., 1994). Immunization with A. baumannii OMPs ensued significant rise in protective immune parameters (McConnell et al., 2011; Alzubaidi and Alkozai, 2015; Bazmara et al., 2019) and antibodies against OMPs passively protected experimental animals (Goel and Kapil, 2001). Clinical studies frequently identify differential expression of OMPs in antibiotic resistant A. baumannii strains, establishing their role in conferring resistance (Cuenca et al., 2003; Yun et al., 2008; Vashist et al., 2010; Moganty et al., 2011; Mostachio et al., 2012). Here, we explore and summarize how antibiotic resistance and virulence in A. baumannii is mediated by different OMPs like OmpA, CarO and OprD.

TABLE 1.

Structure and function of major outer membrane proteins of A. baumannii.

| Name of porin | Molecular weight | Structure | Proposed role in A. baumannii | References |

| OmpA | 28–36 kDa | Eight-stranded Beta barrel shaped | Cytotoxic protein. Mediates attachment to host cells via fibronectin. | Choi et al., 2005; Smani et al., 2012; Confer and Ayalew, 2013 |

| CarO | 25/29 kDa | Eight-stranded beta barrel shaped | Uptake of glycine and ornithine. Also implicated in carbapenem resistance. | Limansky et al., 2002; Siroy et al., 2005; Zahn et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2019 |

| OprD/OccAB1 | 43 kDa | Eighteen-stranded beta-barrel shaped | Allows diffusion of basic amino acids and beta-lactam class of antibiotics into the cell. | Dupont et al., 2005; Zahn et al., 2016 |

| Omp33-36 | 33–36 kDa | Yet to be studied | Implicated in imipenem resistance. Induces apoptosis in host cells by activating caspases 3 and 9. | Clark, 1996; Rumbo et al., 2014 |

| AbuO | 50.2 kDa (Theoretical) | Three domains—four-stranded beta barrel, α-helical barrel and α- β mixed barrel | Homolog of E. coli TolC protein. Involved in pH and bile salt tolerance. | Srinivasan et al., 2015 |

| DcaP | 47–50 kDa | Sixteen-stranded beta-barrel shaped | An Omp with preference for anionic compounds. Involved in transport of phthalates into the cell. | Bhamidimarri et al., 2019 |

| OmpW | Yet to be studied | Eight-stranded beta-barrel shaped. (Theoretical) | Serves as a colistin binding site. Facilitates iron uptake into the cell. | Catel-Ferreira et al., 2016 |

OmpA

OmpA, a beta barrel-shaped monomeric protein (Park et al., 2011) is one of the most abundant OMPs (Gribun et al., 2003), which has been reported to impart drug resistance to A. baumannii by allowing slower diffusion of negatively charged beta-lactam antibiotics (Nitzan et al., 2002) and virulence (Sato and Nakae, 1991; Sato et al., 2017; Sánchez-Encinales et al., 2017) by its toxicity to host cells. Clinical isolates of A. baumannii overexpressing OmpA arbitrate higher morbidity and even mortality in patients (Sato et al., 2017; Sánchez-Encinales et al., 2017). The global repressor H-NS binds to the promoter region of OmpA gene and gene locus A1S_0316 and the two component system BfmSR function as a possible anti-repressor and repressor of OmpA in A. baumannii, respectively (Liou et al., 2014; Oh et al., 2020).

Role of OmpA in Antibiotic Resistance in A. baumannii

Being the most abundant porin in A. baumannii, the role of OmpA in antibiotic resistance was more prominent in disruption mutants of the gene, which showed increased susceptibility to nalidixic acid, chloramphenicol, aztreonam, imipenem, and meropenem. Besides diffusion, research indicates that OmpA possibly couples with efflux pumps and forces out antibacterial compounds from the periplasm (Smani et al., 2013; Fahmy et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2020). OmpA also couples to A. baumannii peptidoglycan (PG) via its C-terminal region, where Asp271 and Arg286 bind to diaminopimelic acid of PG (Park et al., 2012). This binding may regulate outer membrane vesicle (OMV) production and the membrane stability in the bacteria (Moon et al., 2012). OMVs with OmpA in their membrane (Walzer et al., 2006; Jin et al., 2011; Yun et al., 2018) mediate antibiotic resistance by actively siphoning extracellular drugs (Agarwal et al., 2019). Recently, resistance to colistin, a last-resort antibiotic, was also attributed to the presence of OmpA in A. baumannii. An isogenic mutant of OmpA resulted in loss of cell wall integrity, thus making the bacterium 20-fold more sensitive to colistin (Kwon et al., 2019) and 5.3 fold more sensitive to trimethoprim (Kwon et al., 2017) than wild type A. baumannii. The distinctive role of OmpA in conferring antibiotic resistance thrusts researchers to discover novel antibacterials against the protein. In one study, a novel diazabicyclooctenone beta-lactamase inhibitor that inhibits major classes of carbapenemases and in turn potentiates sulbactam activity was shown to be OmpA-dependent (Iyer et al., 2018). OmpA blockers can function synergistically with last resort antibiotics like colistin in eradicating MDR strains of A. baumannii (Vila-Farrés et al., 2017; Parra-Millán et al., 2018). OmpA also interacts with antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) of diverse origin and confers resistance against them (Lin et al., 2015; Guo Y. et al., 2018). Minimum inhibitory concentrations of human AMP LL-37 and bovine AMP BMAP-28 increased upon binding to N-terminal region of OmpA. The multifaceted role of OmpA in A. baumannii membrane permeability and cell wall integrity indicates its potential as a candidate for novel antibacterial development via chemical genetic screens.

Role of OmpA in A. baumannii Adherence and Invasion of Host Cells

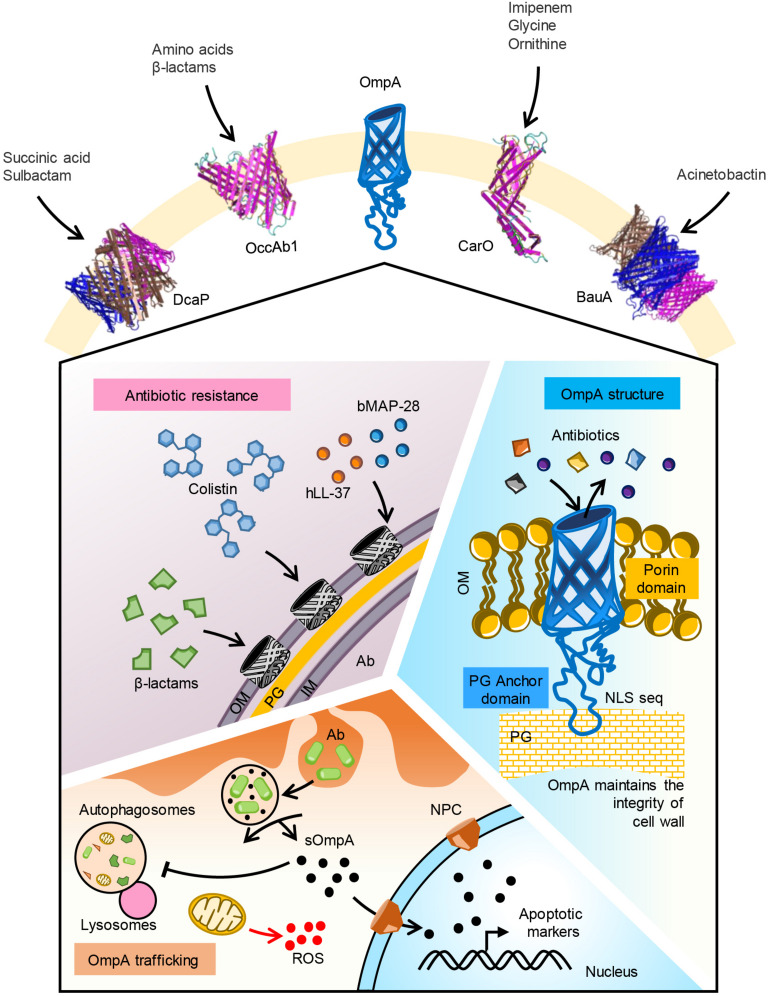

Besides their distinguishable role in antibiotic resistance, OMPs confer virulence to A. baumannii. The bacterium is capable of invading and persisting in host epithelial and immune cells (Figure 1). The primary requisite for invasion is to adhere to the host cells, which is mediated by many virulence factors expressed by A. baumannii viz., OmpA (Nie et al., 2020), BapA (Brossard and Campagnari, 2012), fimbrial like protrusions (Mortensen and Skaar, 2012). A. baumannii adherence to host cells can be both host cell and bacterial sequence-type specific. For instance, two types of adherence patterns have been elucidated in A. baumannii; dispersed adherence of bacteria to the host cells, and adherence of clusters of bacteria at localized areas of the host cells (Lee et al., 2006). Bacterial clusters can be a result of amyloidogenic BAP protein mediated biofilm formation. Interestingly, OmpA specifically mediates bacterial binding to healthy cells than cancerous cells (Choi et al., 2008c). A. baumannii cells devoid of OmpA were found to be less virulent to human airway epithelium due to decreased adherence to cells (Gaddy, 2010) and formed weaker biofilms (Gaddy et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2020).

FIGURE 1.

Function of major OMPs in A. baumannii. Five major OMPs with their substrate specificity is shown. OmpA porin mediates uptake of β-lactam and colistin antibiotics. Human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 and bovine AMP BMAP-28 may bind to the porin. OmpA pore size is optimal for uptake of iron siderophores like acenitobactin. A coiled loop in the C-terminal region of the protein binds to peptidoglycan maintaining the membrane integrity. Phagocytosed A. baumannii releases OmpA into the cytoplasm of host cells. Secreted OmpA inhibits lysosome fusion to autophagosomes, enters into mitochondria inducing ROS generation. Secreted OmpA actively localizes to nucleus via nuclear pore complex where it activates apoptotic markers like caspases. Ab, A. baumannii; OM, outer membrane; PG, peptidoglycan; IM, inner membrane; sOmpA, secreted OmpA; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Following adherence to host cells, A. baumannii invades into the cell cytoplasm. The bacterial penetration into epithelial cells is microfilament- and microtubule-dependent following zipper-like mechanism (Choi et al., 2008c). Upon internalization, A. baumannii cells localize to membrane-bound vacuoles and finally traffic to the nucleus. Bacterial cells actively divide and finally kill the host cell to release into the blood stream. In this process, OmpA actively assists bacterial invasion, although by unknown mechanisms (Kim et al., 2016). Iron homeostasis is found to be a key factor regulating the survival of A. baumannii in the cytoplasm (Gaddy, 2010). Other adherence factors like BapA are not found to mediate invasion of A. baumannii (Brossard and Campagnari, 2012; De Gregorio et al., 2015) indicating that OmpA specific pathways regulate A. baumannii virulence. The functional dynamics of such a feature for a protein can be emphasized succinctly by looking into immune responses in the host.

Immune Response Configuration Against A. baumannii OmpA

In healthy individuals, A. baumannii cells in the blood stream and airways are actively phagocytosed by circulatory or tissue-resident immune cells like macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells (DCs), etc. (Harding et al., 2018) before leading to fulminant A. baumannii sepsis, although the latter is the case frequently encountered in immunocompromised patients. A. baumannii induces host cell cytotoxicity by targeting mitochondrial system and nuclear localization. In epithelial cells, OmpA induces the surface expression of Toll-like receptor 2 and the production of inducible nitric oxide synthase (Kim et al., 2008). Phagocytosed bacteria release several structural and cytoplasmic proteins that induce cytotoxicity directly (e.g., Type VI secretion system effector enzymes, and toxins) or indirectly by activating caspases (e.g., OmpA). In macrophages and epithelial cells, OmpA triggers autophagy, albeit incomplete, by preventing the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes, activating MAPK/JNK signaling pathway (Kim et al., 2008; An and Su, 2019) and enhancing the levels of phosphorylated JNK, p38, ERK and c-Jun (An et al., 2019). Early response in DCs treated with OmpA includes augmenting the expression of CD40, CD54, CD80, CD86 and MHC-I and II surface markers. The marker expression is accompanied by secretion of Th-1 promoting IL-12 (Lee et al., 2007). However, upon prolonged exposure, secreted OmpA in DCs targets mitochondria and induces production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Lee et al., 2008 and 2010). ROS stimulates early-onset apoptosis and delayed-onset necrosis in DCs, thus impairing T-cell response against A. baumannii. Besides induction of ROS, OmpA in conjunction with carbonic anhydrase IX stimulates DCs to generate potent anti-tumor immune response against renal cell carcinoma (Kim B.R. et al., 2011; Kim D.Y. et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2012).

All these observations in the host indicate that OmpA might be toxic in nature, unlike other outer membrane proteins. The toxicity of A. baumannii OmpA can be attributed to its unique structural features and vast diversity of alleles (Viale and Evans, 2020) with conserved domains. OmpA protein is comprised of two domains; an N-terminal 8-stranded β-barrel domain and a C-terminal periplasmic peptidoglycan binding domain. OmpA possesses a basic amino-acid rich signal termed nuclear localization signal (NLS) ‘KTKEGRAMNRR’ (Choi et al., 2007) on its C-terminal domain. Karyopherin β family proteins on nuclear pore complex recognize the NLS via its lysine (K) residues and shuttle OmpA to nucleus from cytoplasm. It can thus be speculated that OmpA devoid of NLS can be a non-toxic variant. Studies to reduce the host cell toxicity of recombinant A. baumannii revealed the importance of both N and C-terminal regions and the importance of lysine residues in NLS sequence. A synthetic OmpA with mutations at K320 and K322 to Alanine, replacing “NADEEFWN” sequence with “YKYDFDGVNRGTRGTSEEGTL” and deleting N-terminal signal sequence and “VVQPGQEAAAPAAAQ” at C-terminal resulted in least toxic but highly immunogenic OmpA (Jahangiri et al., 2017). In addition to NLS, the N-terminal region of OmpA is bioinformatically predicted to be more immunogenic (Darbandian and Sefid, 2016). The epitopes “QIQDSEHSGKMVAKRQ” at position 100–115 and “HTSFDKLPEGGRAT” at position 125–138 are delineated best by Ellipro software. A peptide at N-terminal region located at 24–50 position, “VTVTPLLLGYTFQDSQHNNGGKDGNLT” alone is immunogenic and elicited similar levels serum antibodies like OmpA (Mehdinejadiani et al., 2019). It is clear that OmpA is toxic to host when secreted and when intact, it provides antibiotic resistance to the bacterium. Whether these observations can be implied to the clinical manifestations of A. baumannii is yet to be elucidated.

CarO

Carbapenem susceptibility porin or CarO was first reported in imipenem (IMP) sensitive A. baumannii isolates that acquired resistance upon the loss of a 29 kDa protein (Limansky et al., 2002). CarO is an 8-stranded beta barrel-shaped outer membrane channel protein that does not have a continuous channel (Mussi et al., 2005 and 2011; Siroy et al., 2005; Zahn et al., 2015) but mediates influx of beta lactams (selectively imipenem) into A. baumannii (Mussi et al., 2005). However, contradicting these observations, liposome model system embedded with CarO revealed its ability to transport small amino acids such as glycine and ornithine, but not carbapenem antibiotics (Zahn et al., 2016). Despite this lonesome tangential observation, the excessive evidence from diverse research groups denotes the role of CarO in antibiotic resistance.

CarO is classified into two sub-groups; CarOa and CarOb; of which CarOb exhibits a two-fold greater specificity for IMP (Catel-Ferreira et al., 2011). However, there has been a recent call to rethink the CarO classification system based on phylogenetic analysis (Catel-Ferreira et al., 2011; Novovic et al., 2015). So far, at least six polymorphic variants of CarO have been reported to co-exist in A. baumannii populations with varied specificities to imipenem, highlighting the importance of the protein. The alterations in CarO gene are posited to be a result of rapid adaptation of A. baumannii to diverse habitats and hosts. Besides gene alterations, conformational changes in primary structure, intra-genic insertion sequences (Lee et al., 2011), posttranscriptional (Kuo et al., 2017) and transcriptional (Fonseca et al., 2013; Cardoso et al., 2016) regulation dramatically affect CarO function (summarized in Supplementary Table 1). The recent identification that CarO is significantly up-regulated in an Hfq deletion mutant strain of A. baumannii indicate that it is kept under post-transcriptional control by the bacterium to regulate its expression in response to the changing environment (Kuo et al., 2017). Finally, the occasional isolation of antibiotic resistant strains with a loss of CarO gene signifies the diversity of resistance mechanisms in A. baumannii (Li et al., 2015). In contrast to these studies linking carbapenem resistance to the loss of CarO, there are a few reports of the presence of CarO porin on the OM of carbapenem resistant clinical isolates of A. baumannii. However, this can possibly be explained by the “porin-localized toxin inactivation” model, where carbapenemases like Oxa-23 interact with the periplasmic region of OMPs like CarO or OmpA to act as an efficient selective filter to inactivate incoming antibacterial compounds (Li et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2016; Royer et al., 2018).

The clinical relevance of CarO has also been ascertained by many hospital epidemiological studies. These revealed that there is a prevalence of CarO deficiency amongst carbapenem resistant isolates expressing BlaOXA (Pajand et al., 2013; Abbasi et al., 2020) and TEM-1 (Nan et al., 2018) genes among the hospital isolates of A. baumannii. Various carbapenem resistant clinical isolates demonstrated a disruption in the CarO gene by insertion sequences like ISAba1, ISAba125, ISAba825, ISAba10, ISAba15, and ISAba36 (Mussi et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2011; Ravasi et al., 2011; Kim and Ko, 2015; Khorsi et al., 2018; Mirshekar et al., 2018). When exposed to a high concentration of monovalent cations, A. baumannii release a variety of OMPs including CarO into the surrounding media and becomes more tolerant to IMP stress. This finding implicated that MICs of antibiotics determined in vitro may not help eradicate A. baumannii infection from within the host system, especially in the case of urinary tract infections where there is the presence of a high concentration of monovalent cations like NaCl and KCl (Hood et al., 2010).

The immunological role of CarO protein in A. baumannii is studied inadequately. Sato et al. (2017) showed that clinical A. baumannii isolates expressing higher CarO mRNA levels negatively regulated TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8 in lung epithelial cells. Recently, CarO has been linked to A. baumannii adhesion and virulence in host cells via inhibition of NF-kβ signaling (Zhang et al., 2019). However, the significance of this observation is debatable as the strain used in the study is ATCC 19606 where expression of CarO is significantly lesser than that of clinical strains (Sato et al., 2017).

OprD

OprD was first identified during outer membrane investigations of carbapenem resistant A. baumannii isolates (Dupont et al., 2005). It is an orthologous protein to a porin involved in the basic amino acid and imipenem transport in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Hancock and Brinkman, 2002). Crystallographic studies of a conserved P. aeruginosa OprD revealed a monomeric 18-stranded β-barrel structure characterized by a very narrow pore constriction (Biswas et al., 2007). The amino acid conservation at structural domains between A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa OprD porins indicate its putative function in A. baumannii. However, sequence and homology analysis of A. baumannii OprD showed that it belongs to P. aeruginosa OprQ, a protein involved in resisting low-iron or magnesium and low oxygen stresses (Catel-Ferreira et al., 2012). Recombinant A. baumannii OprD did not conduct antibiotics but partially bound to Fe2+ and Mg2+ cations. An isogenic deletion mutant of A. baumannii OprD did not affect MICs of β-lactams (Smani and Pachón, 2013), but in A. baylyi spp., a significant reduction in MIC of imipenem, ertapenem and meropenem is observed (Morán-Barrio et al., 2017). Despite these two heralding reports on lack of relationship between OprD and antibiotic resistance in A. baumannii, single nucleotide polymorphisms and insertional elements in OprD have been frequently identified in MDR A. baumannii signifying its role in resistance. For instance, Yang et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016 and Lai et al., 2018 showed SNP clusters in OprD in MDR and tigecycline-resistant A. baumannii, respectively. Downregulation of OprD was observed in MDR (Asai et al., 2014) and pan drug-resistant (Cuenca et al., 2011) A. baumannii clinical strains. Insertion of mobile element ISAba1 upstream to the gene was also associated with increased carbapenem MICs of A. baumannii sequence type 107 strains (Costa et al., 2019). OprD was renamed to OccAB1 by Zahn et al. (2016), while solving its crystal structure. In their work, Zahn et al., resolved structures of four carboxylate channels OccAB1, 2, 3, and 4 and showed that OccAB1 has the largest channel size with corresponding high rates of small-molecule shuttle, including amino acids, sugars, and antibiotics, contrary to previous observations. The particularly large pore size of OccAB1 facilitates the objective translocation of both positive and negative substrates at low energy cost (Benkerrou and Ceccarelli, 2018). On the other hand, OccAB2, OccAB3, and OccAB4 mediate hydroxycinnamate (Smith et al., 2003), vanillate (Segura et al., 1999), and benzoate (Clark et al., 2002) transport, respectively. Being induced by limitation of metal ions, it can be presumed that OccAB1 may play a significant role in combating host-induced nutritional immunity and stress survival.

Diversity in A. baumannii OMP Architecture, Expression, and Function

Besides the above three OMPs, a variety of proteins are identified in the outer membrane of A. baumannii with varied expressions and distinctive roles. One of the most abundant OMPs in A. baumannii is Omp33. Crystal structure of the protein revealed its function as a putative gated channel contributing to low permeability of the outer membrane (Abellón-Ruiz et al., 2018). Intracellular A. baumannii in the host cell expresses DcaP OMP in abundance. Crystallographic studies on DcaP revealed a trimeric porin structure with affinity to dicarboxylic acids and sulbactam (Bhamidimarri et al., 2019). The most abundant OMP under osmotic stress in A. baumannii is Omp38 (Jyothisri et al., 1999). Intracellular A. baumannii secretes Omp38, which localizes to the mitochondria stimulating the release of proapoptotic molecules such as cytochrome c and apoptosis-inducing factor (Choi et al., 2005). Oxidative stress in A. baumannii induces expression of AbuO, a homolog of Escherichia coli TolC OMP involved in resistance to amikacin, carbenicillin, ceftriaxone, meropenem, streptomycin, and tigecycline, and hospital-based disinfectants like benzalkonium chloride and chlorhexidine (Srinivasan et al., 2015). Under iron-limiting conditions, a 76-kDa iron-repressible OMP termed fhuE was overexpressed in A. baumannii to facilitate uptake of xenosiderophores desferricoprogen, rhodotorulic acid and desferrioxamine B (Funahashi et al., 2012). Besides fhuE, two other siderophore (acinetobactin) uptake proteins, BfnH and BauA are also elucidated in the outer membrane of A. baumannii (Sefid and Rasooli, 2012; Aghajani et al., 2019). The translation initiation factor EF-Tu, typically a cytoplasmic protein, is also found to localize in the outer membrane in A. baumannii (Dallo et al., 2012). Membrane associated EF-Tu binds to DsbA protein in the periplasm and assists in disulfide bonding during protein folding (Premkumar et al., 2014). Externally, EF-Tu binds to fibronectin thus mediating host cell adhesion (Dallo et al., 2012; Harvey et al., 2019). Decreased expression of a 33–36 kDa OMP (Clark, 1996; del Mar Tomás et al., 2005) and a 29 kDa (Jeong et al., 2009) is associated with imipenem resistance among A. baumannii. Serodiagnostic studies revealed an antigenic 34.4-kDa OMP specific to sera from A. baumannii infected patients (Islam et al., 2011). Upregulation of this protein along with downregulation of CarO and OprD was found to mediate imipenem resistance (Luo et al., 2011). The protein along with OmpA and TonB-dependant copper receptor was identified as fibronectin binding protein during infection (Smani et al., 2012). In silico exploration into the genome of A. baumannii revealed a nuclease (NucAb), BamA (Oma87), FilF, and TolB in the outer membrane as potential vaccine targets. Immunization with these recombinant proteins protected mice from lethal challenge with A. baumannii (Singh et al., 2014, 2016 and Singh et al., 2017; Garg et al., 2016; Song et al., 2018; Rasooli et al., 2020). In another effort toward developing a subunit vaccine against A. baumannii infections, a fusion protein of OmpK and Omp22 was synthesized which provided significantly greater protection against A. baumannii challenge in mice than those immunized with either of the two proteins individually (Huang et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2017; Guo S.J. et al., 2018).

Conclusion

One of the critical gaps in combating A. baumannii is deciphering its overall membrane permeability. Significant progress has been made during the last decade in our understanding of how A. baumannii OMPs mediate antibiotic resistance and virulence in the host cells. Remarkable breakthroughs have also been made in understanding the regulatory mechanisms behind OMP expression and the mechanisms of antibiotic uptake. However, these efforts fall short in many aspects. The knowledge about in vitro or in vivo OMP assembly and folding dynamics in lipid bilayers is scarce. The crystal structure of most studied A. baumannii OMP, OmpA is still elusive, although NLS domain structure has been resolved. Due to its complex structure and hydrophobic loops in its structure, expression and purification of recombinant OmpA presents various hurdles. The solution of crystal structure is decisive in molecular dynamic studies tracking the antibiotic entry and exit through OMPs. Many questions still remain unanswered. How does the beta barrel assembly complex in A. baumannii function? What are the different chaperones mediating OMP folding in A. baumannii? Does the expression of OMPs in A. baumannii depend on transcription factors alone or is it small RNA mediated? Although in small number, concerted efforts are directed toward solving these problems. Crystal structures of CarO1, CarO2, OccAB1 through 4, DcaP, PiuA, Omp33 BauA have been resolved. Understanding the magnitude of posttranscriptional regulation in A. baumannii OMP synthesis is a necessary goal, as this aspect has been overlooked till date. In the next few years, it is likely that A. baumannii OMP compendium will be resolved with novel insights into its structure, diversity, biogenesis, and expression, furthering our efforts in confronting antibiotic resistance and virulence in A. baumannii.

Author Contributions

SU, AS, and RP conceptualized the manuscript and contributed the ideas on the texts. SU and AS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SU and RP edited the subsequent versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.589234/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abbasi E., Goudarzi H., Hashemi A., Chirani A. S., Ardebili A., Goudarzi M., et al. (2020). Decreased carO gene expression and OXA-type carbapenemases among extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated from burn patients in Tehran, Iran. Acta Microbiol. Immunol Hung. 10.1556/030.2020.01138 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott I., Cerqueira G. M., Bhuiyan S., Peleg A. Y. (2013). Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: laboratory challenges, mechanistic insights and therapeutic strategies. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 11 395–409. 10.1586/eri.13.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abellón-Ruiz J., Zahn M., Baslé A., van den Berg B. (2018). Crystal structure of the Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein Omp33. Acta Crystallogr D Struct. Biol. Struct. Biol. 74(Pt 9), 852–860. 10.1107/S205979831800904X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal B., Karthikeyan R., Gayathri P., RameshBabu B., Ahmed G., Jagannadham M. V. (2019). Studies on the mechanism of multidrug resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii by proteomic analysis of the outer membrane vesicles of the bacterium. J. Proteins Proteo 10 1–15. 10.1007/s42485-018-0001-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajani Z., Rasooli I., Mousavi Gargari S. L. (2019). Exploitation of two siderophore receptors, BauA and BfnH, for protection against Acinetobacter baumannii infection. APMIS 127 753–763. 10.1111/apm.12992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzubaidi A. N., Alkozai Z. M. (2015). Immunogenic properties of outer membrane protein of Acinetobacter baumannii that loaded on chitosan nanoparticles. Am. J. Bio Med. 3 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- An Z., Huang X., Zheng C., Ding W. (2019). Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A induces HeLa cell autophagy via MAPK/JNK signaling pathway. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 309 97–107. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An Z., Su J. (2019). Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein 34 elicits NLRP3 inflammasome activation via mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species in RAW264. 7 macrophages. Microbes Infect. 21 143–153. 10.1016/j.micinf.2018.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadollahi P., Akbari M., Soroush S., Taherikalani M., Asadollahi K., Sayehmiri K., et al. (2012). Antimicrobial resistance patterns and their encoding genes among Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated from burned patients. Burns 38 1198–1203. 10.1016/j.burns.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai S., Umezawa K., Iwashita H., Ohshima T., Ohashi M., Sasaki M., et al. (2014). An outbreak of blaOXA-51-like- and blaOXA-66-positive Acinetobacter baumannii ST208 in the emergency intensive care unit. J. Med. Microbiol. 63(Pt 11), 1517–1523. 10.1099/jmm.0.077503-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazmara H., Rasooli I., Jahangiri A., Sefid F., Astaneh S. D. A., Payandeh Z. (2019). Antigenic properties of iron regulated proteins in Acinetobacter baumannii: an in silico approach. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 25 205–213. 10.1007/s10989-017-9665-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bazyleu A., Kumar A. (2014). Incubation temperature, osmolarity, and salicylate affect the expression of resistance-nodulation-division efflux pumps and outer membrane porins in Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC19606T. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 357 136–143. 10.1111/1574-6968.12530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkerrou D., Ceccarelli M. (2018). Free energy calculations and molecular properties of substrate translocation through OccAB porins. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20 8533–8546. 10.1039/c7cp08299a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benmahmod A. B., Said H. S., Ibrahim R. H. (2019). Prevalence and Mechanisms of Carbapenem Resistance among Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates in Egypt. Microb. Drug Resist. 25 480–488. 10.1089/mdr.2018.0141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhamidimarri S. P., Zahn M., Prajapati J. D., Schleberger C., Söderholm S., Hoover J., et al. (2019). A multidisciplinary approach toward identification of antibiotic scaffolds for Acinetobacter baumannii. Structure 27 268.e6–280.e6. 10.1016/j.str.2018.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya T., Sharma A., Akhter J., Pathania R. (2017). The small molecule IITR08027 restores the antibacterial activity of fluoroquinolones against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii by efflux inhibition. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 50 219–226. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S., Mohammad M. M., Patel D. R., Movileanu L., van den Berg B. (2007). Structural insight into OprD substrate specificity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14 1108–1109. 10.1038/nsmb1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borneleit P., Kleber H. P. (1991). “The outer membrane of acinetobacter: structure-function relationships,” in The Biology of Acinetobacter, Federation of European Microbiological Societies Symposium Series, Vol. 57, eds Towner K. J., Bergogne-Bérézin E., Fewson C. A. (Boston, MA: Springer; ). 10.1007/978-1-4899-3553-3_18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvet P. J., Grimont P. A. (1987). Identification and biotyping of clinical isolates of Acinetobacter. Ann. Inst. Pasteur Microbiol. 138 569–578. 10.1016/0769-2609(87)90042-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brossard K. A., Campagnari A. A. (2012). The Acinetobacter baumannii biofilm-associated protein plays a role in adherence to human epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 80 228–233. 10.1128/IAI.05913-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso J. P., Cayô R., Girardello R., Gales A. C. (2016). Diversity of mechanisms conferring resistance to β-lactams among OXA-23-producing Acinetobacter baumannii clones. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 85 90–97. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catel-Ferreira M., Coadou G., Molle V., Mugnier P., Nordmann P., Siroy A., et al. (2011). Structure-function relationships of CarO, the carbapenem resistance-associated outer membrane protein of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66 2053–2056. 10.1093/jac/dkr267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catel-Ferreira M., Nehmé R., Molle V., Aranda J., Bouffartigues E., Chevalier S., et al. (2012). Deciphering the function of the outer membrane protein OprD homologue of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56 3826–3832. 10.1128/AAC.06022-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catel-Ferreira M., Marti S., Guillon L., Jara L., Coadou G., Molle V., et al. (2016). The outer membrane porin OmpW of Acinetobacter baumannii is involved in iron uptake and colistin binding. FEBS Lett. 590 224–231. 10.1002/1873-3468.12050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. H., Hyun S. H., Kim J., Lee Y. C., Seol S. Y., Cho D. T., et al. (2008a). Nuclear translocation and DNAse I-like enzymatic activity of Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 288 62–67. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01323.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. H., Hyun S. H., Lee J. Y., Lee J. S., Lee Y. S., Kim S. A., et al. (2008b). Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A targets the nucleus and induces cytotoxicity. Cell Microbiol. 10 309–319. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. H., Lee J. S., Lee Y. C., Park T. I., Lee J. C. (2008c). Acinetobacter baumannii invades epithelial cells and outer membrane protein A mediates interactions with epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 8:216. 10.1186/1471-2180-8-216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. H., Lee E. Y., Lee Y. C., Park T. I., Kim H. J., Hyun S. H., et al. (2005). Outer membrane protein 38 of Acinetobacter baumannii localizes to the mitochondria and induces apoptosis of epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 7 1127–1138. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00538.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. H., Lee J. S., Lee J. C. (2007). “A versatile role of outer membrane protein a in pathogenesis of Acinetobacter baumannii,” in Proceedings of the Microbiological Society of Korea Conference, (South Korea: The Microbiological Society of Korea; ), 107–108. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. B. (1996). Imipenem resistance among Acinetobacter baumannii: association with reduced expression of a 33-36 kDa outer membrane protein. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 38 245–251. 10.1093/jac/38.2.245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark T. J., Momany C., Neidle E. L. (2002). The benPK operon, proposed to play a role in transport, is part of a regulon for benzoate catabolism in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. Microbiology 148(Pt 4), 1213–1223. 10.1099/00221287-148-4-1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Confer A. W., Ayalew S. (2013). The OmpA family of proteins: roles in bacterial pathogenesis and immunity. Vet. Microbiol. 163 207–222. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa R. F., Cayô R., Matos A. P., Girardello R., Martins W., Carrara-Marroni F. E., et al. (2019). Temporal evolution of Acinetobacter baumannii ST107 clone: conversion of blaOXA-143 into blaOXA-231 coupled with mobilization of ISAba1 upstream occAB1. Res. Microbiol. 170 53–59. 10.1016/j.resmic.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca F. F., Pascual A., Martínez L. M., Conejo M. C., Perea E. J. (2003). Evaluation of SDS-polyacrylamide gel systems for the study of outer membrane protein profiles of clinical strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Basic Microbiol. 43 194–201. 10.1002/jobm.200390022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca F. F., Smani Y., Gómez-Sánchez M. C., Docobo-Pérez F., Caballero-Moyano F. J., Domínguez-Herrera J., et al. (2011). Attenuated virulence of a slow-growing pandrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii is associated with decreased expression of genes encoding the porins CarO and OprD-like. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 38 548–549. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallo S. F., Zhang B., Denno J., Hong S., Tsai A., Haskins W., et al. (2012). Association of Acinetobacter baumannii EF-Tu with cell surface, outer membrane vesicles, and fibronectin. ScientificWorldJournal 2012:128705. 10.1100/2012/128705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbandian P., Sefid F. (2016). Evaluation of OMP A (Outer Membrane Protein A) linear and conformational epitopes in Acinetobacter baumannii. Int. J. Adv. Biotechnol. Res. 7:3. [Google Scholar]

- De Gregorio E., Del Franco M., Martinucci M., Roscetto E., Zarrilli R., Di Nocera P. P. (2015). Biofilm-associated proteins: news from Acinetobacter. BMC Genomics 16:933. 10.1186/s12864-015-2136-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Mar Tomás M., Beceiro A., Pérez A., Velasco D., Moure R., Villanueva R., et al. (2005). Cloning and functional analysis of the gene encoding the 33- to 36-kilodalton outer membrane protein associated with carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49 5172–5175. 10.1128/AAC.49.12.5172-5175.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont M., Pagès J. M., Lafitte D., Siroy A., Bollet C. (2005). Identification of an OprD homologue in Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Proteome Res. 4 2386–2390. 10.1021/pr050143q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy I. L., Amin M. H., Mohamed F. A., Hashem A. G. (2018). Colonization of multi-drug resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from tertiary hospitals in Egypt and the possible role of the outer membrane protein (OmpA.). Int. Res. J. Pharm. 9 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Fernando D., Kumar A. (2012). Growth phase-dependent expression of RND efflux pump- and outer membrane porin-encoding genes in Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67 569–572. 10.1093/jac/dkr519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca E. L., Scheidegger E., Freitas F. S., Cipriano R., Vicente A. C. (2013). Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii from Brazil: role of CarO alleles expression and blaOXA-23 gene. BMC Microbiol. 13:245. 10.1186/1471-2180-13-245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funahashi T., Tanabe T., Mihara K., Miyamoto K., Tsujibo H., Yamamoto S. (2012). Identification and characterization of an outer membrane receptor gene in Acinetobacter baumannii required for utilization of desferricoprogen, rhodotorulic acid, and desferrioxamine B as xenosiderophores. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 35 753–760. 10.1248/bpb.35.753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaddy J. A. (2010). Acinetobacter baumannii Virulence Attributes: The Roles of Outer Membrane Protein A, Acinetobactin-mediated Iron Acquisition Functions, and Blue Light Sensing Protein A. Doctoral dissertation, Miami University, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Gaddy J. A., Tomaras A. P., Actis L. A. (2009). The Acinetobacter baumannii 19606 OmpA protein plays a role in biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces and in the interaction of this pathogen with eukaryotic cells. Infect. Immun. 77 3150–3160. 10.1128/IAI.00096-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg N., Singh R., Shukla G., Capalash N., Sharma P. (2016). Immunoprotective potential of in silico predicted Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane nuclease. NucAb. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 306 1–9. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2015.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnacho-Montero J., Ortiz-Leyba C., Fernández-Hinojosa E., Aldabó-Pallás T., Cayuela A., Marquez-Vácaro J. A., et al. (2005). Acinetobacter baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia: epidemiological and clinical findings. Intensive Care Med. 31 649–655. 10.1007/s00134-005-2598-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giammanco A., Calà C., Fasciana T., Dowzicky M. J. (2017). Global assessment of the activity of tigecycline against multidrug-resistant gram-negative pathogens between 2004 and 2014 as part of the tigecycline evaluation and surveillance trial. mSphere 2:e00310-16. 10.1128/mSphere.00310-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel V. K., Kapil A. (2001). Monoclonal antibodies against the iron regulated outer membrane proteins of Acinetobacter baumannii are bactericidal. BMC Microbiol. 1:16. 10.1186/1471-2180-1-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribun A., Nitzan Y., Pechatnikov I., Hershkovits G., Katcoff D. J. (2003). Molecular and structural characterization of the HMP-AB gene encoding a pore-forming protein from a clinical isolate of Acinetobacter baumannii. Curr. Microbiol. 47 434–443. 10.1007/s00284-003-4050-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S. J., Ren S., Xie Y. E. (2017). Recombinant expression and purification of the OmpK outer membrane protein of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Pathog. Biol. 12 837–839. [Google Scholar]

- Guo S. J., Ren S., Xie Y. E. (2018). Evaluation of the protective efficacy of a fused OmpK/Omp22 protein vaccine Candidate against Acinetobacter baumannii Infection in Mice. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 31 155–158. 10.3967/bes2018.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Xun M., Han J. (2018). A bovine myeloid antimicrobial peptide (BMAP-28) and its analogs kill pan-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii by interacting with outer membrane protein A (OmpA). Medicine 97:e12832. 10.1097/MD.0000000000012832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock R. E., Brinkman F. S. (2002). Function of Pseudomonas porins in uptake and efflux. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56 17–38. 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson K. G., Kale V. C., Desai A. J. (1994). The possible involvement of cell surface and outer membrane proteins of Acinetobacter sp. A3 in crude oil degradation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 122 275–279. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07180.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harding C. M., Hennon S. W., Feldman M. F. (2018). Uncovering the mechanisms of Acinetobacter baumannii virulence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16 91–102. 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey K. L., Jarocki V. M., Charles I. G., Djordjevic S. P. (2019). The diverse functional roles of elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu) in microbial pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 10:2351. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood M. I., Jacobs A. C., Sayood K., Dunman P. M., Skaar E. P. (2010). Acinetobacter baumannii increases tolerance to antibiotics in response to monovalent cations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54 1029–1041. 10.1128/AAC.00963-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Yao Y., Wang S., Xia Y., Yang X., Long Q., et al. (2016). Immunization with a 22-kDa outer membrane protein elicits protective immunity to multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci. Rep. 6:20724. 10.1038/srep20724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwa W. E., Subramaniam G., Mansor M. B., Yan O. S., Gracie, Anbazhagan D., et al. (2010). Iron regulated outer membrane proteins (IROMPs) as potential targets against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. isolated from a Medical Centre in Malaysia. Indian J. Med. Res. 131 578–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam A. H., Singh K. K., Ismail A. (2011). Demonstration of an outer membrane protein that is antigenically specific for Acinetobacter baumannii. Diagn. Microbiol. Infec.t Dis. 69 38–44. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer R., Moussa S. H., Durand-Réville T. F., Tommasi R., Miller A. (2018). Acinetobacter baumannii OmpA is a selective antibiotic permeant porin. ACS Infect. Dis. 4 373–381. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahangiri A., Rasooli I., Owlia P., Fooladi A. A., Salimian J. (2017). In silico design of an immunogen against Acinetobacter baumannii based on a novel model for native structure of outer membrane protein A. Microb. Pathog. 105 201–210. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H. W., Cheong H. J., Kim W. J., Kim M. J., Song K. J., Song J. W., et al. (2009). Loss of the 29-kilodalton outer membrane protein in the presence of OXA-51-like enzymes in Acinetobacter baumannii is associated with decreased imipenem susceptibility. Microb. Drug Resist. 15 151–158. 10.1089/mdr.2009.0828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J. S., Kwon S. O., Moon D. C., Gurung M., Lee J. H., Kim S. I., et al. (2011). Acinetobacter baumannii secretes cytotoxic outer membrane protein A via outer membrane vesicles. PLoS One 6:e17027. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jyothisri K., Deepak V., Rajeswari M. R. (1999). Purification and characterization of a major 40 kDa outer membrane protein of Acinetobacter baumannii. FEBS lett. 443 57–60. 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01679-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorsi K., Messai Y., Ammari H., Hamidi M., Bakour R. (2018). ISAba36 inserted into the outer membrane protein gene carO and associated with the carbapenemase gene blaOXA-24-like in Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 15 107–108. 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. R., Yang E. K., Kim D. Y., Kim S. H., Moon D. C., Lee J. H., et al. (2012). Generation of anti-tumour immune response using dendritic cells pulsed with carbonic anhydrase IX-Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A fusion proteins against renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 167 73–83. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04489.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. R., Yang E. K., Kim S. H., Moon D. C., Kim H. J., Lee J. C., et al. (2011). Immunostimulatory activity of dendritic cells pulsed with carbonic anhydrase IX and Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A for renal cell carcinoma. J. Microbiol. 49 115–120. 10.1007/s12275-011-1037-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. Y., Kim B., Kim S. H., Lee J., Kim J. C., Park C. H., et al. (2011). 242 Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein a enhance immune responses to renal cell carcinoma vaccines targeting carbonic anhydrase IX. J. Urol. 185:e98 10.1016/j.juro.2011.02.311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. H., Ko K. S. (2015). ISAba15 inserted into outer membrane protein gene carO in Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Bacteriol. Virol. 45 51–53. 10.4167/jbv.2015.45.1.51 27650591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. A., Yoo S. M., Hyun S. H., Choi C. H., Yang S. Y., Kim H. J., et al. (2008). Global gene expression patterns and induction of innate immune response in human laryngeal epithelial cells in response to Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 54 45–52. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00446.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. W., Oh M. H., Jun S. H., Jeon H., Kim S. I., Kim K., et al. (2016). Outer membrane Protein A plays a role in pathogenesis of Acinetobacter nosocomialis. Virulence 7 413–426. 10.1080/21505594.2016.1140298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo H. Y., Chao H. H., Liao P. C., Hsu L., Chang K. C., Tung C. H., et al. (2017). Functional Characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii Lacking the RNA Chaperone Hfq. Front. Microbiol. 8:2068. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H. I., Kim S., Oh M. H., Na S. H., Kim Y. J., Jeon Y. H., et al. (2017). Outer membrane protein A contributes to antimicrobial resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii through the OmpA-like domain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 3012–3015. 10.1093/jac/dkx257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H. I., Kim S., Oh M. H., Shin M., Lee J. C. (2019). Distinct role of outer membrane protein A in the intrinsic resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii and Acinetobacter nosocomialis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 67 33–37. 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C. C., Chen C. C., Lu Y. C., Chuang Y. C., Tang H. J. (2018). In vitro activity of cefoperazone and cefoperazone-sulbactam against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Drug. Resist. 12 25–29. 10.2147/IDR.S181201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. R., Lee J. H., Park M., Park K. S., Bae I. K., Kim Y. B., et al. (2017). Biology of Acinetobacter baumannii: pathogenesis, antibiotic resistance mechanisms, and prospective treatment options. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 7:55. 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. C., Koerten H., van den Broek P., Beekhuizen H., Wolterbeek R., van den Barselaar M., et al. (2006). Adherence of Acinetobacter baumannii strains to human bronchial epithelial cells. Res. Microbiol. 157 360–366. 10.1016/j.resmic.2005.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. S., Choi C. H., Kim J. W., Lee J. C. (2010). Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A induces dendritic cell death through mitochondrial targeting. J. Microbiol. 48 387–392. 10.1007/s12275-010-0155-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. S., Kim J. W., Choi C. H., Lee W. K., Chung H. Y., Lee J. C. (2008). Anti-tumor activity of Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A on dendritic cell-based immunotherapy against murine melanoma. J. Microbiol. 46 221–227. 10.1007/s12275-008-0052-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. S., Lee J. C., Lee C. M., Jung I. D., Jeong Y. I., Seong E. Y., et al. (2007). Outer membrane protein A of Acinetobacter baumannii induces differentiation of CD4+ T cells toward a Th1 polarizing phenotype through the activation of dendritic cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 74 86–97. 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Kim C. K., Lee H., Jeong S. H., Yong D., Lee K. (2011). A novel insertion sequence, ISAba10, inserted into ISAba1 adjacent to the bla(OXA-23) gene and disrupting the outer membrane protein gene CarO in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55 361–363. 10.1128/AAC.01672-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Li Z., Qu Y., Li H., Xing J., Hu D. (2015). A study of outer membrane protein and molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 27 611–615. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2015.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limansky A. S., Mussi M. A., Viale A. M. (2002). Loss of a 29-kilodalton outer membrane protein in Acinetobacter baumannii is associated with imipenem resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40 4776–4778. 10.1128/jcm.40.12.4776-4778.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M. F., Lan C. Y. (2014). Antimicrobial resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: From bench to bedside. World J. Clin. Cases 2 787–814. 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i12.787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M. F., Lin Y. Y., Lan C. Y. (2020). Characterization of biofilm production in different strains of Acinetobacter baumannii and the effects of chemical compounds on biofilm formation. PeerJ 8:e9020. 10.7717/peerj.9020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M. F., Tsai P. W., Chen J. Y., Lin Y. Y., Lan C. Y. (2015). OmpA binding mediates the effect of antimicrobial peptide LL-37 on Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS One 10:e0141107. 10.1371/journal.pone.0141107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou M. L., Soo P. C., Ling S. R., Kuo H. Y., Tang C. Y., Chang K. C. (2014). The sensor kinase BfmS mediates virulence in Acinetobacter baumannii. Microbiol. Immunol. Infec. 47 275–281. 10.1016/j.jmii.2012.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Cui Y., Zheng B., Jiang S., Yu W., Shen P., et al. (2016). Analysis of tigecycline resistance development in clinical Acinetobacter baumannii isolates through a combined genomic and transcriptomic approach. Sci. Rep. 6:26930. 10.1038/srep26930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L., Jiang X., Wu Q., Wei L., Li J., Ying C. (2011). Efflux pump overexpression in conjunction with alternation of outer membrane protein may induce Acinetobacter baumannii resistant to imipenem. Chemotherapy 57 77–84. 10.1159/000323620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell M. J., Domínguez-Herrera J., Smani Y., López-Rojas R., Docobo-Pérez F., Pachón J. (2011). Vaccination with outer membrane complexes elicits rapid protective immunity to multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Infect. Immun. 79 518–526. 10.1128/IAI.00741-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehdinejadiani K., Bandehpour M., Hashemi A., Ranjbar M. M., Taheri S., Jalali S. A., et al. (2019). In Silico design and evaluation of Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein a antigenic peptides as vaccine candidate in immunized mice. Iran J. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 18 655–663. 10.18502/ijaai.v18i6.2178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirshekar M., Shahcheraghi F., Azizi O., Solgi H., Badmasti F. (2018). Diversity of Class 1 integrons, and disruption of carO and dacD by insertion sequences among Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates in Tehran. Iran. Microb. Drug. Resist. 24 359–366. 10.1089/mdr.2017.0152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moganty R. R., Vashistt J., Tiwari V., Kapil A. (2011). Differential expression of Outer membrane proteins in early stages of meropenem-resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Integrat. OMICS 1 281–287. 10.5584/jiomics.v1i2.67 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moon D. C., Choi C. H., Lee J. H., Choi C. W., Kim H. Y., Park J. S., et al. (2012). Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A modulates the biogenesis of outer membrane vesicles. J. Microbiol. 50 155–160. 10.1007/s12275-012-1589-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morán-Barrio J., Cameranesi M. M., Relling V., Limansky A. S., Brambilla L., Viale A. M. (2017). The Acinetobacter outer membrane contains multiple specific channels for carbapenem β-lactams as revealed by kinetic characterization analyses of imipenem permeation into Acinetobacter baylyi Cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:e01737-16. 10.1128/AAC.01737-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen B. L., Skaar E. P. (2012). Host-microbe interactions that shape the pathogenesis of Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Cell Microbiol. 14 1336–1344. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01817.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostachio A. K., Levin A. S., Rizek C., Rossi F., Zerbini J., Costa S. F. (2012). High prevalence of OXA-143 and alteration of outer membrane proteins in carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. isolates in Brazil. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 39 396–401. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussi M. A., Limansky A. S., Relling V., Ravasi P., Arakaki A., Actis L. A., et al. (2011). Horizontal gene transfer and assortative recombination within the Acinetobacter baumannii clinical population provide genetic diversity at the single carO gene, encoding a major outer membrane protein channel. J. Bacterial. 193 4736–4748. 10.1128/JB.01533-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussi M. A., Limansky A. S., Viale A. M. (2005). Acquisition of resistance to carbapenems in multidrug-resistant clinical strains of Acinetobacter baumannii: natural insertional inactivation of a gene encoding a member of a novel family of beta-barrel outer membrane proteins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49 1432–1440. 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1432-1440.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussi M. A., Relling V. M., Limansky A. S., Viale A. M. (2007). CarO, an Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein involved in carbapenem resistance, is essential for L-ornithine uptake. FEBS Lett. 581 5573–5578. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.10.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan L. I., Zhang H. J., Wang Y., Meng Q. I., Guo W. X., Wang Z., et al. (2018). Study on the drug resistance of clinical strain of Acinetobacter baumannii mediated by TEM-1 beta-lactamases and porin CarO. Tianjin Med. J. 46 246–250. [Google Scholar]

- Nie D., Hu Y., Chen Z., Li M., Hou Z., Luo X., et al. (2020). Outer membrane protein A (OmpA) as a potential therapeutic target for Acinetobacter baumannii infection. J. Biomed. Sci. 27:26. 10.1186/s12929-020-0617-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H. (2003). Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67 593–656. 10.1128/mmbr.67.4.593-656.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitzan Y., Deutsch E. B., Pechatnikov I. (2002). Diffusion of beta-lactam antibiotics through oligomeric or monomeric porin channels of some gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Microbiol. 45 446–455. 10.1007/s00284-002-3778-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitzan Y., Pechatnikov I., Bar-El D., Wexler H. (1999). Isolation and characterization of heat-modifiable proteins from the outer membrane of Porphyromonas asaccharolytica and Acinetobacter baumannii. Anaerobe 5 43–50. 10.1006/anae.1998.0181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novovic K., Mihajlovic S., Vasiljevic Z., Filipic B., Begovic J., Jovcic B. (2015). Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii from Serbia: revision of CarO classification. PLoS One 10:e0122793. 10.1371/journal.pone.0122793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh K. W., Kim K., Islam M. M., Jung H. W., Lim D., Lee J. C., et al. (2020). Transcriptional Regulation of the Outer Membrane Protein A in Acinetobacter baumannii. Microorganisms 8:706. 10.3390/microorganisms8050706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajand O., Rezaee M. A., Nahaei M. R., Mahdian R., Aghazadeh M., Soroush M. H., et al. (2013). Study of the carbapenem resistance mechanisms in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii: comparison of burn and non-burn strains. Burns 39 1414–1419. 10.1016/j.burns.2013.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. S., Lee W. C., Choi S., Yeo K. J., Song J. H., Han Y. H., et al. (2011). Overexpression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of the periplasmic domain of outer membrane protein A from Acinetobacter baumannii. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 67(Pt 12), 1531–1533. 10.1107/S1744309111038401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. K., Jung S. I., Park K. H., Kim S. H., Ko K. S. (2012). Characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter spp. other than Acinetobacter baumannii in South Korea. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 39 81–85. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Millán R., Vila-Farrés X., Ayerbe-Algaba R., Varese M., Sánchez-Encinales V., Bayó N., et al. (2018). Synergistic activity of an OmpA inhibitor and colistin against colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanistic analysis and in vivo efficacy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73 3405–3412. 10.1093/jac/dky343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg A. Y., Seifert H., Paterson D. L. (2008). Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21 538–582. 10.1128/CMR.00058-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pormohammad A., Mehdinejadiani K., Gholizadeh P., Nasiri M. J., Mohtavinejad N., Dadashi M., et al. (2020). Global prevalence of colistin resistance in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Microb. Pathog. 139:103887. 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar L., Kurth F., Duprez W., Grøftehauge M. K., King G. J., Halili M. A., et al. (2014). Structure of the Acinetobacter baumannii dithiol oxidase DsbA bound to elongation factor EF-Tu reveals a novel protein interaction site. J. Biol. Chem. 289 19869–19880. 10.1074/jbc.M114.571737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasooli I., Abdolhamidi R., Jahangiri A., Darvish Alipour Astaneh S. (2020). Outer membrane protein, Oma87 Prevents Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 1–8. 10.1007/s10989-020-10056-0 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravasi P., Limansky A. S., Rodriguez R. E., Viale A. M., Mussi M. A. (2011). ISAba825, a functional insertion sequence modulating genomic plasticity and bla(OXA-58) expression in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55 917–920. 10.1128/AAC.00491-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodloff A. C., Dowzicky M. J. (2017). Antimicrobial susceptibility among european gram-negative and gram-positive isolates collected as part of the tigecycline evaluation and surveillance Trial (2004-2014). Chemotherapy 62 1–11. 10.1159/000445022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer S., de Campos P. A., Araújo B. F., Ferreira M. L., Gonçalves I. R., Batistão D., et al. (2018). Molecular characterization and clonal dynamics of nosocomial blaOXA-23 producing XDR Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS One 13:e0198643. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbo C., Tomás M., Moreira E. F., Soares N. C., Carvajal M., Santillana E., et al. (2014). The Acinetobacter baumannii Omp33-36 porin is a virulence factor that induces apoptosis and modulates autophagy in human cells. Infect. Immun. 82 4666–4680. 10.1128/IAI.02034-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Encinales V., Álvarez-Marín R., Pachón-Ibáñez M. E., Fernández-Cuenca F., Pascual A., Garnacho-Montero J., et al. (2017). Overproduction of outer membrane protein A by Acinetobacter baumannii as a risk factor for nosocomial pneumonia. Bacteremia, and Mortality Rate Increase. J. Infect. Dis. 215 966–974. 10.1093/infdis/jix010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Nakae T. (1991). Outer membrane permeability of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and its implication in antibiotic resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 28 35–45. 10.1093/jac/28.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y., Unno Y., Kawakami S., Ubagai T., Ono Y. (2017). Virulence characteristics of Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates vary with the expression levels of omps. J. Med. Microbiol. 66 203–212. 10.1099/jmm.0.000394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sefid F., Rasooli I. (2012). “Cleft analysis Of BauA outer membrane protein in Acinetobacter Baumannii,” in Bioinformatics conference, (Tehran: Shahed University; ). [Google Scholar]

- Segura A., Bünz P. V., D’Argenio D. A., Ornston L. N. (1999). Genetic analysis of a chromosomal region containing vanA and vanB, genes required for conversion of either ferulate or vanillate to protocatechuate in Acinetobacter. J. Bacteriol. 181 3494–3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen B., Joshi S. G. (2016). Studies on Acinetobacter baumannii involving multiple mechanisms of carbapenem resistance. J. Appl. Microbiol. 120 619–629. 10.1111/jam.13037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Dubey V., Sharma R., Devnath K., Gupta V. K., Akhter J., et al. (2018). The unusual glycine-rich C terminus of the Acinetobacter baumannii RNA chaperone Hfq plays an important role in bacterial physiology. J. Biol. Chem. 293 13377–13388. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M., Sapkota J., Jha B., Mishra B., Bhatt C. P. (2019). Biofilm formation and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producer among Acinetobacter species isolated in a tertiary care hospital: a descriptive cross-sectional study. JNMA J. Nepal. Med. Assoc. 57 424–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievert D. M., Ricks P., Edwards J. R., Schneider A., Patel J., Srinivasan A., et al. (2013). Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the centers for disease control and prevention, 2009-2010. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 34 1–14. 10.1086/668770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Capalash N., Sharma P. (2017). Immunoprotective potential of BamA, the outer membrane protein assembly factor, against MDR Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci. Rep. 7:12411. 10.1038/s41598-017-12789-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Garg N., Capalash N., Kumar R., Kumar M., Sharma P. (2014). In silico analysis of Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein BamA as a potential immunogen. Int. J. Pure Appl. Sci. Technol. 21 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Garg N., Shukla G., Capalash N., Sharma P. (2016). Immunoprotective efficacy of Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein. FilF, Predicted In silico as a potential vaccine candidate. Front. Microbiol. 7:158. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siroy A., Molle V., Lemaître-Guillier C., Vallenet D., Pestel-Caron M., Cozzone A. J., et al. (2005). Channel formation by CarO, the carbapenem resistance-associated outer membrane protein of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49 4876–4883. 10.1128/AAC.49.12.4876-4883.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skariyachan S., Taskeen N., Ganta M., Venkata Krishna B. (2019). Recent perspectives on the virulent factors and treatment options for multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 45 315–333. 10.1080/1040841X.2019.1600472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slusky J. S., Dunbrack R. L., Jr. (2013). Charge asymmetry in the proteins of the outer membrane. Bioinformatics 29 2122–2128. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smani Y., Dominguez-Herrera J., Pachón J. (2013). Association of the outer membrane protein Omp33 with fitness and virulence of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Infect. Dis. 208 1561–1570. 10.1093/infdis/jit386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smani Y., McConnell M. J., Pachón J. (2012). Role of fibronectin in the adhesion of Acinetobacter baumannii to host cells. PLoS One 7:e33073. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smani Y., Pachón J. (2013). Loss of the OprD homologue protein in Acinetobacter baumannii: impact on carbapenem susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:677. 10.1128/AAC.01277-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. A., Weaver V. B., Young D. M., Ornston L. N. (2003). Genes for chlorogenate and hydroxycinnamate catabolism (hca) are linked to functionally related genes in the dca-pca-qui-pob-hca chromosomal cluster of Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69 524–532. 10.1128/aem.69.1.524-532.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Zhang H., Zhang D., Xie W., Zhao G. (2018). Bioinformatics analysis and epitope screening of a potential vaccine antigen TolB from Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein. Infect. Genet. Evol. 62 73–79. 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan V. B., Vaidyanathan V., Rajamohan G. (2015). AbuO, a TolC-like outer membrane protein of Acinetobacter baumannii, is involved in antimicrobial and oxidative stress resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59 1236–1245. 10.1128/AAC.03626-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohidinia M., Moshtaghioun S. M., Sefid F., Falahati A. (2019). Functional exposed amino acids of CarO analysis as a potential vaccine candidate in Acinetobacter Baumannii. Int. J. Peptide Res. Thera. 26, 1185–1197. 10.1007/s10989-019-09923-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai Y. K., Liou C. H., Lin J. C., Fung C. P., Chang F. Y., Siu L. K. (2020). Effects of different resistance mechanisms on antimicrobial resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: a strategic system for screening and activity testing of new antibiotics. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 55:105918. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk J. H., Endimiani A., Graubner C., Gerber V., Perreten V. (2019). Acinetobacter in veterinary medicine, with an emphasis on Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 16 59–71. 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashist J., Tiwari V., Kapil A., Rajeswari M. R. (2010). Quantitative profiling and identification of outer membrane proteins of beta-lactam resistant strain of Acinetobacter baumannii. Proteome Res. 9 1121–1128. 10.1021/pr9011188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viale A. M., Evans B. A. (2020). Microevolution in the major outer membrane protein OmpA of Acinetobacter baumannii. Microb. Genom. 6:e000381. 10.1099/mgen.0.000381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila-Farrés X., Parra-Millán R., Sánchez-Encinales V., Varese M., Ayerbe-Algaba R., Bayó N., et al. (2017). Combating virulence of Gram-negative bacilli by OmpA inhibition. Sci. Rep. 7 14683. 10.1038/s41598-017-14972-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walzer G., Rosenberg E., Ron E. Z. (2006). The Acinetobacter outer membrane protein A (OmpA) is a secreted emulsifier. Environ. Microbiol. 8 1026–1032. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.00994.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Yuan Q., Ling B. (2015). Analysis of the expression of the outer membrane protein in carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Int. J. Lab. Med. 2015 2295–2296. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner L. M., Webb A. K., Limbago B., Dudeck M. A., Patel J., Kallen A. J., et al. (2016). Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the national healthcare safety network at the centers for disease control and prevention, 2011-2014. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 37 1288–1301. 10.1017/ice.2016.174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization [WHO] (2017). Global Priority list of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria to Guide Researach, Discovery and Development of New Antibiotics. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Chavez J. D., Schweppe D. K., Zheng C., Weisbrod C. R., Eng J. K., et al. (2016). In vivo protein interaction network analysis reveals porin-localized antibiotic inactivation in Acinetobacter baumannii strain AB5075. Nat. Commun. 7:13414. 10.1038/ncomms13414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Huang L., Barnie P. A., Su Z., Mi Z., Chen J., et al. (2015). Characterization and distribution of drug resistance associated β-lactamase, membrane porin and efflux pump genes in MDR A. baumannii isolated from Zhenjiang. China. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8 15393–15402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun S. H., Choi C. W., Park S. H., Lee J. C., Leem S. H., Choi J. S., et al. (2008). Proteomic analysis of outer membrane proteins from Acinetobacter baumannii DU202 in tetracycline stress condition. J. Microbiol. 46 720–727. 10.1007/s12275-008-0202-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun S. H., Park E. C., Lee S. Y., Lee H., Choi C. W., Yi Y. S., et al. (2018). Antibiotic treatment modulates protein components of cytotoxic outer membrane vesicles of multidrug-resistant clinical strain, Acinetobacter baumannii DU202. Clin. Proteomics 15:28. 10.1186/s12014-018-9204-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn M., Bhamidimarri S. P., Baslé A., Winterhalter M., van den Berg B. (2016). Structural insights into outer membrane permeability of Acinetobacter baumannii. Structure 24 221–231. 10.1016/j.str.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn M., D’Agostino T., Eren E., Baslé A., Ceccarelli M., van den Berg B. (2015). Small-molecule transport by CarO, an abundant eight-stranded β-Barrel outer membrane protein from Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Mol. Biol. 427 2329–2339. 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Liang W., S-G Xu, Mei J., Di Y. Y., Lan H. H., et al. (2019). CarO promotes adhesion and colonization of Acinetobacter baumannii through inhibiting NF-êB pathways. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 12 2518–2524. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S. Y., Jiang D. Y., Xu P. C., Zhang Y. K., Shi H. F., Cao H. L., et al. (2015). An investigation of drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections in a comprehensive hospital of East China. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 14:7. 10.1186/s12941-015-0066-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Yao Y., Zhu B., Ren D., Yang Q., Fu Y., et al. (2019). Risk factors for acquisition and mortality of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia: a retrospective study from a Chinese hospital. Medicine 98:e14937. 10.1097/MD.0000000000014937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L. J., Chen X. Y., Hou P. F. (2019). Mutation of CarO participates in drug resistance in imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 33:e22976. 10.1002/jcla.22976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.