Abstract

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors improve survival in BRCA-mutant high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. As a result, germline and somatic BRCA1/2 testing has become standard practice in women diagnosed with ovarian cancer. We outline changes in testing and detection rates of germline BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants (PVs) in cases of non-mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer diagnosed during three eras, spanning 12 years, within the North West of England, and compare the uptake of cascade testing in families identified by oncology-led mainstreaming versus regional genetics clinics. Eras included: Period 1 (20% risk threshold for testing): between January 2007 and May 2013; Period 2 (10% risk threshold for testing): between June 2013 and October 2017 and; Period 3 (mainstream testing): between November 2017 and November 2019. A total of 1081 women underwent germline BRCA1/2 testing between January 2007 and November 2019 and 222 (20.5%) were found to have a PV. The monthly testing rate increased by 3.3-fold and 2.5-fold between Periods 1–2 and Periods 2–3, respectively. A similar incidence of germline BRCA1/2 PVs were detected in Period 2 (17.2%) and Period 3 (18.5%). Uptake of cascade testing from first-degree relatives was significantly lower in those women undergoing mainstream testing compared with those tested in regional genetics clinics (31.6% versus 47.3%, P = 0.038). Mainstream testing allows timely detection of germline BRCA1/2 status to select patients for PARP inhibitors, but shortfalls in the uptake of cascade testing in first-degree relatives requires optimisation to broaden benefits within families.

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Risk factors

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the commonest cause of gynaecological-related cancer death in Europe and North America [1]. Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is histologically classified into five main subtypes, including: high-grade serous (HGS), low-grade serous, endometrioid, clear cell and mucinous [2]. High-grade serous carcinoma accounts for approximately 80% of all EOC and 70% of all ovarian tumours. These highly aggressive tumours have an insidious clinical prodrome and commonly present with advanced stage disease in which cure is unlikely [3]. For advanced stage HGS carcinoma, standard therapy includes cytoreductive surgery and platinum/taxane-based chemotherapy plus maintenance bevacizumab or poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors [4, 5]. Randomised trials have demonstrated that PARP inhibitors significantly improve survival in HGS carcinoma, with the greatest benefits in BRCA-mutant tumours [6–14]. It is estimated that approximately 20% of all HGS carcinomas contain a germline or somatic BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant (PV) [15, 16].

The incorporation of PARP inhibitors in standard therapy for HGS carcinoma has significantly increased demand for germline and somatic BRCA1/2 testing [17–23]. As a result, mainstream (oncology-led) germline BRCA1/2 testing has been implemented in unselected populations of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Although mainstream testing has increased the absolute number of BRCA1/2 variants detected, it is not known how this new model of testing impacts on cascade testing of first-degree relatives. In this study, we outline how the rate of germline BRCA1/2 testing in cases of non-mucinous EOC, diagnosed in the North West of England, has varied across three eras of testing, spanning 12 years. Moreover, we report the uptake of pre-symptomatic testing in families in whom the germline BRCA1/2 PV was identified through mainstreaming versus standard regional genetics testing.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

Women diagnosed with non-mucinous epithelial cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube or peritoneum who underwent germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing between 1st January 2007 and 1st November 2019 were included. Index cases with a diagnosis of carcinosarcoma were also included. Germline BRCA1/2 testing took place primarily in the genetics clinics at St Mary’s Hospital, Manchester. In the latter 24 months, mainstream testing was carried out by oncologists or surgeons in gynaecological oncology clinics in the North West England including: The Christie Hospital (Manchester), Royal Preston Hospital (Preston) and Blackpool Victoria Hospital (Blackpool). Pathogenic (ACMG Class 5) or likely pathogenic (ACMG Class 4) BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants are included and will be referred to collectively as BRCA1/2 PVs throughout this paper [24]. Variants of unknown clinical significance (ACMG Class 3) were excluded. Index cases of mucinous ovarian carcinoma or non-EOC were excluded.

All women from an Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry found to have a BRCA1/2 founder mutation were excluded because the Manchester BRCA Scoring System was not designed to assess risk in this population [25]. In the North West of England, all women from an Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry undergo founder testing for the three common germline PVs (BRCA1:c.68_69del, BRCA1:c.5266dup and BRCA2:c.5946del) before full gene sequencing.

A family history was defined as any index case of non-mucinous EOC with a first-degree or second-degree relative with breast, ovarian, prostate or pancreatic cancer. An index case was categorised as ‘sporadic appearing’ non-mucinous EOC if there was no first-degree or second-degree relative with breast, ovarian, prostate or pancreatic cancer.

All demographic data were extracted from clinical case notes and electronic patient records.

Germline BRCA1/2 testing

Germline BRCA1/2 variants were detected by testing DNA extracted from peripheral circulating lymphocytes. Next generation sequencing was used to detect variants throughout the whole coding sequence of BRCA1/2, including at least 15 base pairs beyond each exon-intron junction. Single nucleotide variants and small deletions, duplications, insertions and insertion-deletions variants (<40 base pairs) were called using an inhouse bioinformatic pipeline that has been validated to detect heterozygous and mosaic variants to an allele fraction ≥0.04.

Testing for large genomic rearrangements (e.g., whole exon/gene deletions or duplications) in BRCA1/2 was performed by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) [26]. The MLPA probe kits P002-D1 (BRCA1 P002-D1 used from August 2015; prior to this, earlier versions of P002 probe kit were used) and P045-C1 (BRCA2 P045-C1 used from December 2016; prior to this, earlier versions of P045 probe kits were used) (MRC Holland, Amsterdam, Netherlands) were used. Amplified ligation products were subject to fragment analysis using an ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyser and size called using GeneMapper 2.0 (Applied Biosystems®, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Calling of copy-number status was performed using data exported from GeneMapper using custom developed MLPA spreadsheets that report relative dosage quotient for each probe compared to five reference control samples. All MLPA assays were performed in duplicate for confirmation of results.

Pre-symptomatic testing for germline BRCA1/2 PVs was performed using bi-directional Sanger sequencing using BigDye v3.1 chemistry and analysis was performed using Mutation Surveyor. Polymerase chain reaction primers for pre-symptomatic testing were designed to avoid hybridising to the sites of common polymorphic variants (minor allele frequency > 0.01). Pre-symptomatic testing for pathogenic copy-number variants was carried out using MLPA using the MRC Holland probe-sets outlined above. Familial PV positive controls were run alongside all pre-symptomatic tests.

Manchester BRCA Scoring System

The Manchester BRCA Scoring System is a paper-based model that can be utilised to determine the combined BRCA1 and BRCA2 carrier probability of an index case (Table 1) [27]. The development of the Manchester BRCA Scoring System was based on empirical data gathered from the Manchester genetic variant screening programme [28]. Each individual, from one side of the family, is scored for BRCA1 and BRCA2 separately. For an index case of breast cancer or ovarian cancer, or, an unaffected relative of an index case of ovarian cancer (<60 years old), the BRCA1 and BRCA2 scores are adjusted according to pathology. A Manchester Score of 15–19 equates to a combined BRCA1/2 probability of 10%, and 20 points a probability of 20%.

Table 1.

The Manchester Scoring System with pathology adjustment.

| BRCA1 | BRCA2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer, age at diagnosis | ||

| FBC, <30 | 6 | 5 |

| FBC, 30–39 | 4 | 4 |

| FBC, 40–49 | 3 | 3 |

| FBC, 50–59 | 2 | 2 |

| FBC, >59 | 1 | 1 |

| MBC, <60 | 5 | 8 |

| MBC, >59 | 5 | 5 |

| Ovarian cancer, <60 | 8 | 5 |

| Ovarian cancer, >59 | 5 | 5 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 0 | 1 |

| Prostate cancer, <60 | 0 | 2 |

| Prostate cancer, >59 | 0 | 1 |

| Pathology adjustment | ||

| Breast cancer (index case only) | ||

| Grade 3 | +2 | 0 |

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Grade 1 | −2 | 0 |

| ER positive | −1 | 0 |

| ER negative | +1 | 0 |

| Triple-negativea | +4 | 0 |

| HER2 amplifiedb | −6 | 0 |

| Ductal carcinoma in situ | −2 | 0 |

| Lobular | −2 | 0 |

| Ovarian cancer (any case in familyc) | ||

| Mucinous, germ cell or borderline tumours | 0 | 0 |

| High-grade serous, <60 | +2 | 0 |

| Adopted (no known status in blood relatives) | +2 | +2 |

Each individual and family relevant tumour (from one side of the family only) is given a numerical weight and these are summated to provide a score for each of the two genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2 [23]. Score ‘Cancer, age at diagnosis’ first and then adjust score through ‘Pathology adjustment’.

FBC female breast cancer, MBC male breast cancer, ER oestrogen receptor.

aAlso score grade in addition to triple-negative.

bAlso score grade and ER status in addition to HER2 status.

cOnly if the relative is not related to index case through more than one unaffected woman aged > 60 years.

Eras assessed

Three time periods were assessed. In 2004, NICE published familial breast cancer guidelines indicating that testing should use a 20% likelihood threshold for implementing germline testing for BRCA1/2 variants. This changed to a 10% threshold in May 2013. In November 2017, after training of oncologists in obtaining informed consent for germline BRCA1/2 testing, all non-mucinous EOC cases could be offered testing for germline BRCA1/2 PVs in oncology clinics, although clinicians were encouraged to refer any index case with a family history to their regional genetics centre. We therefore used an initial time period of 77 months from January 2007 to May 2013 when a 20% threshold applied (Period 1). The second period was a 53-month period from June 2013 to October 2017 when a 10% threshold pertained (Period 2). The final 24 months from November 2017 to November 2019 was the mainstreaming period (Period 3).

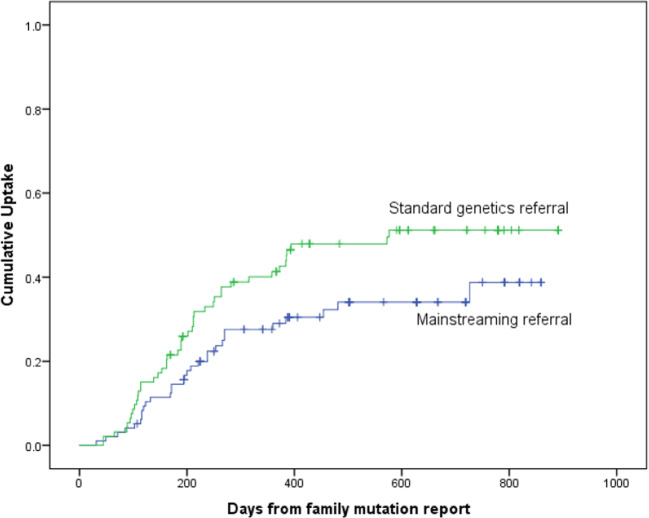

Uptake of pre-symptomatic testing was assessed by Kaplan–Meier statistics. Pre-symptomatic testing involved a targeted search for a germline BRCA1/2 PV that had been found in an index case with non-mucinous EOC within the family.

Results

One thousand and eighty-one women of non-Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry underwent germline BRCA1/2 testing following a diagnosis of non-mucinous EOC. In total, 222 women (20.5%) had a germline BRCA1/2 PV (BRCA1: 131, BRCA2: 91).

The mean age at diagnosis of EOC was lower in BRCA1 (52.1 years, range: 33–75) than BRCA2 heterozygotes (59.5 years, range: 33–86) and germline wild type (58.15 years, range: 20–87). This was similar during Period 3 (mainstreaming): BRCA1: 53.1 years (range: 33–67), BRCA2: 60.5 years (range: 47–82) and germline wild type: 60.5 years (range: 23–85).

The monthly rate of germline BRCA1/2 sample testing rose 3.3-fold from Period 1 to Period 2 and 8.4-fold from Period 1 to Period 3 (Table 2). Despite lowering of (Period 2) and subsequent removal of the testing thresholds (Period 3) there was an equivalent incidence of germline BRCA1/2 PVs detected in Period 2 (17.2%) and Period 3 (18.5%) (Table 2). However, the monthly rate of germline BRCA1/2 detection rose 2.7-fold from Period 2 to Period 3 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Monthly sampling and detection rates of germline BRCA1/2 PVs over three eras in the North West of England.

| Era | No. tested | gBRCA1/2 PV | Monthly sampling rate | Monthly detection rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 2007 to May 2013 (20% threshold) Period 1 | 183 | 61 (33.3) | 2.38 | 0.79 |

| June 2013 to October 2017 (10% threshold) Period 2 | 418 | 72 (17.2) | 7.89 | 1.36 |

| November 2017 to November 2019 (mainstreaming) Period 3 | 480 | 89 (18.5) | 20 | 3.71 |

| Total | 1081 | 222 (20.5) | – | – |

Data presented as number or number (percentage).

gBRCA1/2 PVs germline BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants.

The pathology-adjusted Manchester Score performed well, with scores ≤ 14 points associated with BRCA1/2 likelihoods < 10% (Table 3). Index cases of non-mucinous EOC with no relevant personal or family history had detection rates of 11.3% if <60 years old and 5.95% if ≥60 years old. Of the 20 BRCA2 heterozygotes diagnosed at ≥60 years old, 6 (30%) had no relevant personal or family history. In the mainstreaming era, most BRCA1/2 PVs were detected in women diagnosed with HGS carcinoma, although women with this histological diagnosis were more likely to be tested (Table 4).

Table 3.

Germline BRCA1/2 PVs detected in non-mucinous EOC index cases from January 2007 to November 2019 in the North West of England categorised according to Manchester Score.

| Manchester Score (pathology adjusted) | No. tested | gBRCA1/2 PVs |

|---|---|---|

| Single ovary only, non-mucinous, ≥60 years old | 168 | 10 (6.0) |

| Single ovary only, non-mucinous, <60 years old | 294 | 35 (11.9) |

| Manchester Score <11 | 186 | 10 (5.4) |

| Manchester Score 11–14 | 126 | 11 (8.7) |

| Manchester Score 15–19 | 451 | 64 (14.2) |

| Manchester Score 20–24 | 131 | 44 (33.6) |

| Manchester Score 25–39 | 160 | 71 (44.4) |

| Manchester Score ≥40 | 27 | 22 (81.5) |

| Total | 1081 | 222 (20.5) |

Data presented as number or number (percentage).

gBRCA1/2 PVs germline BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants.

Table 4.

Germline BRCA1/2 PVs detected in non-mucinous EOC index cases from November 2017 to November 2019 in the North West of England categorised according to histology.

| Histology | No. tested | gBRCA1/2 PVs |

|---|---|---|

| High-grade serous | 427 | 86 (20.1) |

| Low-grade serous | 8 | 0 |

| Endometrioid | 21 | 2 (9.5) |

| Clear cell | 14 | 0 |

| Carcinosarcoma | 11 | 1 (9.1) |

| Total | 481 | 89 (18.5) |

Data presented as number or number (percentage).

gBRCA1/2 PVs germline BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants.

During the mainstream testing period, 50 BRCA1/2 PVs were detected through mainstreaming and 39 from direct referral to clinical genetics, including 18 patients diagnosed with non-mucinous EOC prior to mainstreaming testing. Of the remaining 71/89 BRCA1/2 PVs detected, results were obtained between 6 weeks and 3 years following the date of the ovarian cancer diagnosis (mean: 9 months, median: 6.5 months). Of the 50 mainstream BRCA-positive cases, 6 were from out-of-region and were referred to their own regional genetics service. Three patients died before an appointment with clinical genetics was possible and two were already known to genomic medicine with a BRCA1/2 PV, but apparently not to the oncology service and underwent repeat testing. Referrals were received for 35/39 of the remaining BRCA-positive cases within 6 weeks of the test result being reported. Three referrals were received 3–5 months after the report was issued. In five BRCA-positive cases, reminder letters to oncologists were sent to chase referrals. Patients referred were offered appointments within 10 weeks, but several patients delayed appointments whilst undergoing cancer treatment. Two patients declined appointments, but in one of these families another member had been referred to clinical genetics.

From the 44 families eligible to be seen by the regional genetics service, 39 have been seen and 98 first-degree relatives were eligible for pre-symptomatic testing (Table 5). To date, 31 (31.6%) have undergone pre-symptomatic testing compared to 44/93 (47.3%) from non-mainstreamed families from the same time period (Table 5). Kaplan–Meier uptake curves of pre-symptomatic testing for unaffected first-degree relatives are shown in Fig. 1. There was a significantly higher uptake in those seen through a standard genetics referral compared to those seen through a mainstreaming approach (P = 0.038).

Table 5.

Pre-symptomatic tests in first-degree relatives of germline BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant heterozygotes since November 2017 in the North West of England.

| Index cases since November 2017 | No. of families | Predictive tests | Total unaffected FDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard genetics referral | 39 | 44 | 93 (47.3) |

| Mainstreaming | 39 | 31 | 98 (31.6) |

Data presented as number or number (percentage). There was a significantly higher uptake in those with standard genetics referral compared to those with a mainstreaming approach (P = 0.038).

FDR first-degree relative.

Fig. 1. Kaplan–Meier curve.

Figure 1 shows the difference in cumulative uptake of pre-symptomatic germline BRCA1/2 testing between standard genetics referral (green line) compared to mainstreaming referral (blue line) (P = 0.038).

Discussion

Until recently the model for germline DNA testing for cancer predisposition genes was genetics led with clinical geneticists acting as the ‘gatekeepers’ to access testing of genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2. With the arrival of PARP inhibitors for the treatment of ovarian and breast cancer, which require knowledge of germline BRCA1/2 status prior to prescribing, diagnostic pathways have shifted to curtail specialist genetic counselling for more focused informed consent by oncologists/surgeons [17–22]. The main advantage of this approach is that there is no waiting time for an appointment with clinical genetics. The priority of family screening has therefore been superseded by the drive to establish eligibility for PARP inhibitors in index cases. Now that PARP inhibitors are being used as part of primary therapy in HGS carcinoma, there is an even greater demand for oncology-led germline and somatic BRCA1/2 testing [6–8].

We have evaluated the effect of mainstreaming (oncology led) testing in non-mucinous EOC index cases compared with two previous eras of testing. Testing rates increased approximately eightfold compared to when a 20% threshold pertained (Period 1) and approximately threefold from the 10% era (Period 2). Despite the lack of a threshold during mainstreaming, germline BRCA1/2 PV detection rates remained approximately 18%, only slightly higher than when utilising a 10% threshold during Period 2. However, during mainstream testing the germline BRCA1/2 PV detection rates increased from 0.79 to 3.71 per month, demonstrating the utility of oncology-led testing.

The pathology-adjusted Manchester Score performed as expected with a score of 15 points indicating the 10% threshold and 20 points the 20% threshold. Although likelihood scores are no longer relevant to women diagnosed with ovarian cancer, these scores are still relevant to unaffected relatives where no living relative is available, e.g., a score of 20 points in an affected deceased mother of unknown germline BRCA1/2 status would make her unaffected children eligible for germline testing at the 10% threshold.

The detection rate of germline BRCA1/2 variants in our study was 20.5%; comparable to 22.6% found by Alsop et al. in a similar sized Australian study of 1001 women diagnosed with non-mucinous ovarian cancer [29], but higher than 11.1% described by Song et al. in 2222 cases of EOC [30]. The lower rates of germline BRCA1/2 PVs detected in non-serous tumours likely reflect the differences in biology of the unique histological and molecular subtypes of EOC. Although the numbers of cases of non-serous tumours tested within our cohort was small (<50 cases), the detection rates of <10% germline BRCA1/2 PVs reaffirm the necessity to stratify BRCA1/2 testing by histology.

Whilst the huge upward increment in testing is highly encouraging, our data unlikely represent full uptake. The mean age at testing of around 60 years suggests that older patients are less likely to be tested. This may be because of the initial confusion over whether testing was limited in sporadic appearing index cases aged >60 years old who fell below the 10% detection rate. In BRCA2-positive cases the mean age of onset was similar to germline wild-type cases across all time periods, although the detection rate dropped from approximately 11% in sporadic appearing cases <60 years old to around 6% in those aged ≥60 years. Indeed, we have recently noted that in certain populations, such as women diagnosed with ovarian cancer >60 years old, the frequency of BRCA2 PVs is higher than previously thought; a phenomenon uncovered through population-based testing as opposed to risk-based testing [31].

The rate of uptake of testing in first-degree relatives was significantly less in those from mainstream referrals compared with standard genetics referral. This likely reflects differences in counselling offered, sense of urgency and prioritisation by individuals referred. There is a paucity of literature focused on relatives’ motivations for accepting genetic testing since mainstream testing begun, although uptake in index cases has been noted to be heavily motivated by the desire to protect and inform family members [32]. As mainstream testing continues, this area will require further research.

There was some delay in index cases accessing genetics services during mainstream testing mainly due to women cancelling appointments. This led to an initial slower uptake of pre-symptomatic testing from the date of the index case’s original BRCA1/2 PV report being issued. However, in our analysis we have not considered that mainstreamed women are likely to have undergone germline testing earlier in their treatment pathway, meaning the difference identified may be non-significant.

Conclusions

Mainstreaming has led to an increase in the absolute number of germline BRCA1/2 PVs detected in cases of non-mucinous EOC, demonstrating the clinical utility of this approach to identify patients that may benefit from PARP inhibitors. However, long-term consequences of the impact of germline BRCA-positive results within families require further evaluation.

Acknowledgements

ERW, EJC, EFH, and DGRE are supported by the all Manchester National Institute for Health Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (IS-BRC-1215-20007).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The germline BRCA1/2 database is approved by North Manchester Research Ethics Committee (08/H1006/77). All women included in this study provided informed verbal and/or written consent to undergo germline BRCA1/2 testing.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Nicola Flaum, Robert D. Morgan

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS, Young RH. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2014.

- 3.Lheureux S, Gourley C, Vergote I, Oza AM. Epithelial ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2019;393:1240–53.. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NCCN. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines in ovarian cancer. 2020. https://www.nccn.org/.

- 5.Ledermann JA, Raja FA, Fotopoulou C, Gonzalez-Martin A, Colombo N, Sessa C, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(Suppl 6):vi24–32. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman RL, Fleming GF, Brady MF, Swisher EM, Steffensen KD, Friedlander M, et al. Veliparib with first-line chemotherapy and as maintenance therapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;385:2403–15.. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1909707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez-Martin A, Pothuri B, Vergote I, DePont Christensen R, Graybill W, Mirza MR, et al. Niraparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N. Engl J Med. 2019;381:2391–402. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, Kim BG, Oaknin A, Friedlander M, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495–505.. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1810858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D, Aghajanian C, Oaknin A, Dean A, et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1949–61.. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32440-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, Oza AM, Mahner S, Redondo A, et al. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2154–64.. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F, Gebski V, Penson RT, Oza AM, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1274–84.. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penson RT, Valencia RV, Cibula D, Colombo N, Leath CA, III, Bidzinski M, et al. Olaparib versus nonplatinum chemotherapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO3): a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1164–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swisher EM, Lin KK, Oza AM, Scott CL, Giordano H, Sun J, et al. Rucaparib in relapsed, platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL2 part 1): an international, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:75–87. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30559-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore KN, Secord AA, Geller MA, Miller DS, Cloven N, Fleming GF, et al. Niraparib monotherapy for late-line treatment of ovarian cancer (QUADRA): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:636–48.. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang KL, Mashl RJ, Wu Y, Ritter DI, Wang J, Oh C, et al. Pathogenic germline variants in 10,389 adult cancers. Cell. 2018;173:355–70.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–15. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman B, Lanceley A, Kristeleit RS, Ledermann JA, Lockley M, McCormack M, et al. Mainstreamed genetic testing for women with ovarian cancer: first-year experience. J Med Genet. 2019;56:195–8. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-105140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plaskocinska I, Shipman H, Drummond J, Thompson E, Buchanan V, Newcombe B, et al. New paradigms for BRCA1/BRCA2 testing in women with ovarian cancer: results of the genetic testing in epithelial ovarian cancer (GTEOC) study. J Med Genet. 2016;53:655–61. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-103902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rust K, Spiliopoulou P, Tang CY, Bell C, Stirling D, Phang T, et al. Routine germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing in patients with ovarian carcinoma: analysis of the Scottish real-life experience. BJOG. 2018;125:1451–8. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George A, Riddell D, Seal S, Talukdar S, Mahamdallie S, Ruark E, et al. Implementing rapid, robust, cost-effective, patient-centred, routine genetic testing in ovarian cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29506. doi: 10.1038/srep29506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colombo N, Huang G, Scambia G, Chalas E, Pignata S, Fiorica J, et al. Evaluation of a streamlined oncologist-led BRCA mutation testing and counseling model for patients with ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1300–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kentwell M, Dow E, Antill Y, Wrede CD, McNally O, Higgs E, et al. Mainstreaming cancer genetics: a model integrating germline BRCA testing into routine ovarian cancer clinics. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:130–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan RD, Burghel GJ, Flaum N, Bulman M, Clamp AR, Hasan J, et al. Prevalence of germline pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants in sequential epithelial ovarian cancer cases. J Med Genet. 2019;56:301–7. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans DG, Harkness EF, Plaskocinska I, Wallace AJ, Clancy T, Woodward ER, et al. Pathology update to the Manchester Scoring System based on testing in over 4000 families. J Med Genet. 2017;54:674–81.. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schouten JP, McElgunn CJ, Waaijer R, Zwijnenburg D, Diepvens F, Pals G. Relative quantification of 40 nucleic acid sequences by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans DG, Harkness EF, Plaskocinska I, Wallace AJ, Clancy T, Woodward ER, et al. Pathology update to the Manchester Scoring System based on testing in over 4000 families. J Med Genet. 2017;54:674–81.. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans DG, Eccles DM, Rahman N, Young K, Bulman M, Amir E, et al. A new scoring system for the chances of identifying a BRCA1/2 mutation outperforms existing models including BRCAPRO. J Med Genet. 2004;41:474–80. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.017996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, deFazio A, Emmanuel C, George J, et al. BRCA mutation frequency and patterns of treatment response in BRCA mutation-positive women with ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2654–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song H, Cicek MS, Dicks E, Harrington P, Ramus SJ, Cunningham JM, et al. The contribution of deleterious germline mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2 and the mismatch repair genes to ovarian cancer in the population. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:4703–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flaum N, Crosbie EJ, Woodward ER, Lalloo F, Evans DGR. Challenging the believed proportion of ovarian cancer attributable to BRCA2 versus BRCA1 pathogenic variants. Eur J Cancer. 2020;124:88–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright S, Porteous M, Stirling D, Lawton J, Young O, Gourley C, et al. Patients’ views of treatment-focused genetic testing (TFGT): some lessons for the mainstreaming of BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing. J Genet Couns. 2018;27:1459–72. doi: 10.1007/s10897-018-0261-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]