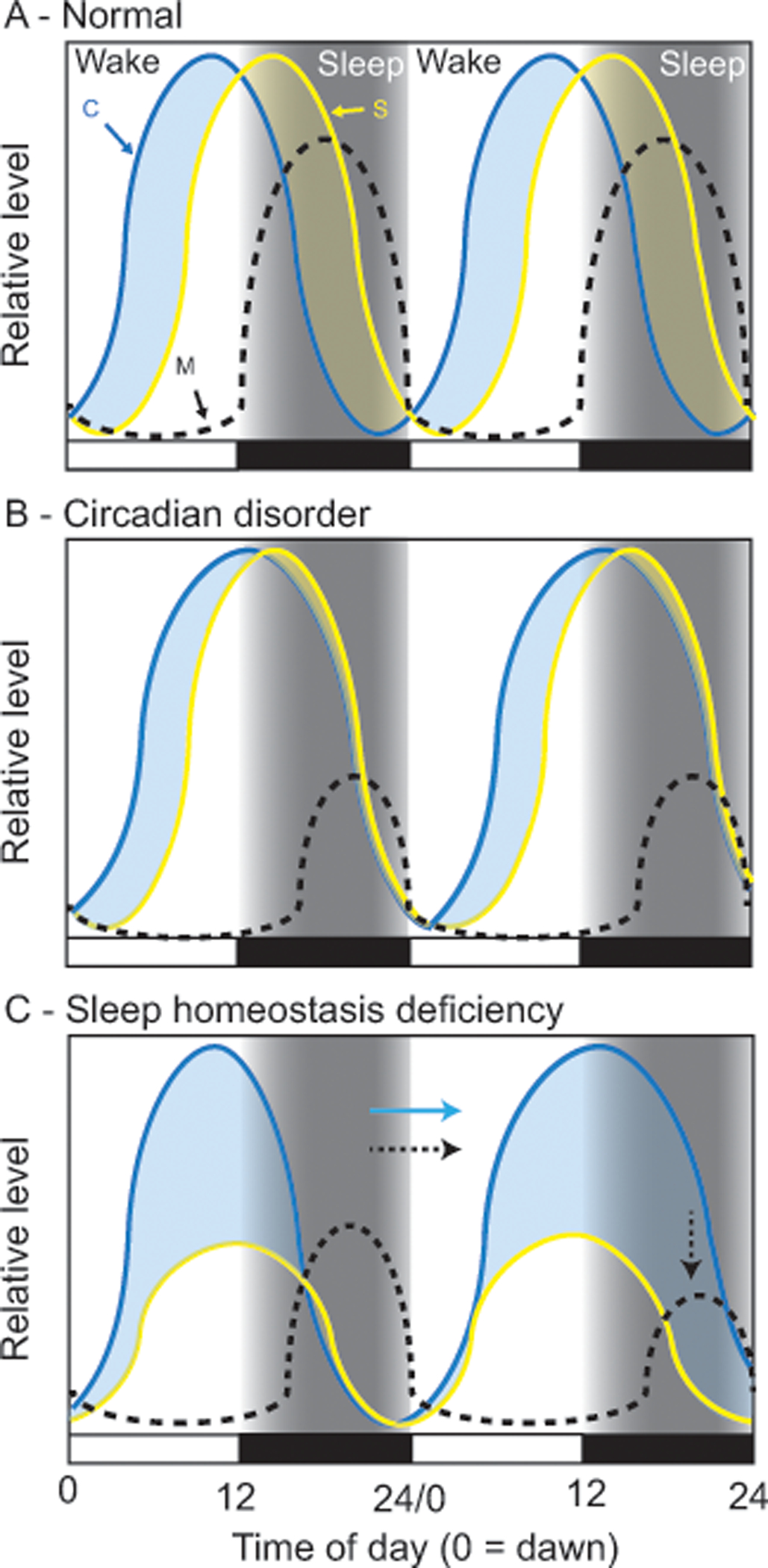

Figure 1: Two-process model depictions of how sleep might be altered in Angelman syndrome.

In these simplified models, Process C (C; circadian clock) provides drive for wakefulness and Process S (S; sleep homoeostasis) builds pressure to sleep. At any time of day, whichever drive is higher dictates sleep-state (light blue shading = wake, yellow shading = sleep). Under normal conditions (A) Wake drive (blue curve), driven by Process C, dominates during the day keeping the subject awake; sleep-drive (yellow curve) is building simultaneously, just at a slower rate. At night, melatonin (M) is produced, the circadian clock stops providing wake drive, and the accumulation of sleep drive causes the subject to fall asleep; sleep causes sleep drive to dissipate. In Angelman syndrome, sleep disorders could be caused by changes to circadian control (B), sleep homeostatic control (C), or both (not shown). Data suggest that AS patients may have a long circadian period and/or a delayed and suppressed nighttime melatonin rhythm, as depicted by Process C and melatonin curves (B). If Process S is normal, then Process C may compete against it during the night, delaying and suppressing both sleep and melatonin production. Alternatively, data also suggest the sleep homeostatic process is blunted (C) and may accumulate less efficiently. In this scenario, overall sleep drive is reduced, leading to decreases in sleep. In either B or C, not sleeping may also lead to an increase of light exposure at night (i.e. turning on lights or TV) that may further contribute to circadian-like deficits in sleep regulation (indicated by the arrows in C).