Abstract

The diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) is one of the most destructive pests to cruciferous plants worldwide. The oligophagous moth primarily utilizes its host volatiles for foraging and oviposition. Chemosensory proteins (CSPs) are soluble carrier proteins with low molecular weight, which recognize and transport various semiochemicals in insect chemoreception. At present, there is limited information on the recognition of host volatiles by CSPs of P. xylostella. Here, we investigated expression patterns and binding characteristics of PxylCSP11 in P. xylostella. The open reading frame of PxylCSP11 was 369-bp encoding 122 amino acids. PxylCSP11 possessed four conserved cysteines, which was consistent with the typical characteristic of CSPs. PxylCSP11 was highly expressed in antennae, and the expression level of PxylCSP11 in male antennae was higher than that in female antennae. Fluorescence competitive binding assays showed that PxylCSP11 had strong binding abilities to several ligands, including volatiles of cruciferous plants, and (Z)-11-hexadecenyl acetate (Z11-16:Ac), a major sex pheromone of P. xylostella. Our results suggest that PxylCSP11 may play an important role in host recognition and spouse location in P. xylostella.

Keywords: chemosensory protein, tissue expression, fluorescence competitive binding, host volatiles

Insects mainly rely on their chemosensory system, especially olfactory repertoires, to distinguish the specific chemical information in the external environment to mediate their behaviors, such as foraging, mating, oviposition, and avoiding natural enemies (Field et al. 2000, Arimura et al. 2009, Hansson and Stensmyr 2011, Leal 2013). The entire olfactory system of insects has become a complex and precise chemical information processing network in the long-term evolution. As one of the most important olfactory organs in insects, antennae are used to perceive chemical cues from the environment (Yan et al. 2014, Li et al. 2018). There is an abundance of olfactory sensilla on antennae. Sensilla basiconica mainly sense host volatiles, and sensilla trichodea detect sex pheromones (Ammagarahalli and Gemeno 2014, Yan et al. 2017, Faucheux et al. 2019). Furthermore, the high sensitivity and specificity of the olfactory system are closely related to olfactory proteins located in antennae, such as odorant binding proteins (OBPs), chemosensory proteins (CSPs), olfactory receptors (ORs), ionotropic receptors (IRs), sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs), and odorant-degrading enzymes (ODEs) (Pelosi et al. 2006, Vogt et al. 2009, Abuin et al. 2011, Leal 2013, Pelosi et al. 2018, Fleischer et al. 2018). The first step in olfactory recognition is the entrance of semiochemicals into the hemolymph through micropores in olfactory sensilla (Kaissling 2001, Pelosi et al. 2006, Kaissling 2009, Leal 2013, Sun et al. 2016). Due to the hydrophilicity of the lymph fluid, hydrophobic odors are transported by carrier proteins to reach the dendritic membranes of sensory neurons (Pelosi et al. 2018). CSPs, as a type of carrier proteins, play a significant role in the process of binding and delivering odors.

CSPs, also known as olfactory specific-D (OS-D) (Mckenna et al. 1994) and sensory appendage proteins (Robertson et al. 1999), are soluble proteins with low molecular weight and are generally composed of 100–120 amino acid residues. Almost all CSPs contain four highly conserved cysteines, which is a typical characteristic of these proteins (Wanner et al. 2004, Zeng et al. 2018b). The first CSP member of insects was obtained from the antennae of Drosophila melanogaster Meigen (Diptera: Drosophilidae) through subtractive cDNA hybridization (Mckenna et al. 1994). Subsequently, CSPs have also been identified from the antennae of different insect species, including Bombyx mori L. (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae) (Gong et al. 2007), Frankliniella occidentalis Pergande (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) (Zhang and Lei 2015), Sitobion avenae Fabricius (Hemiptera: Aphididae) (Xue et al. 2016), and Monochamus alternatus Hope (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) (Ali et al. 2019). Many studies have demonstrated that antennae-enriched CSPs bind and transport a variety of host plant volatiles and/or sex pheromones (Zhang et al. 2013, He et al. 2017, Chen et al. 2018). Three CSPs of Adelphocoris lineolatus Goeze (Hemiptera: Miridae) highly expressed in antennae are related to host recognition (Gu et al. 2012). When Mythimna separate Walker (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) MsepCSP5 specifically expressed in the antennae is silenced by RNAi, the behavioral responses of adults to volatile attractants decrease (Younas et al. 2018).

CSPs are also broadly distributed in other insect tissues, such as head, maxillary palps, labial palps, legs, thorax, wings, proboscis, pheromone glands, and ejaculatory duct, indicating that CSPs have multiple physical functions (Maleszka and Stange 1997, Marchese et al. 2000, Jin et al. 2005, Zhou et al. 2010, Gu et al. 2012, Zhu et al. 2016). Interestingly, a CSP has been demonstrated to participate in the morphological and behavioral transformation of Locusta migratoria Meyen (Orthoptera: Acrididae) from the solitary phase to the gregarious phase (Hassanali et al. 2005). Other special functions of CSPs have also been reported, such as CO2 detection in Cactoblastis cactorum Berg (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) (Maleszka and Stange 1997), leg regeneration of Periplaneta Americana L. (Blattaria: Blattidae) (Kitabayashi et al. 1998), embryonic development of Apis mellifera L. (Hymenoptera: Apidae) (Forêt et al. 2007, Maleszka et al. 2007), and insecticide resistance of Spodoptera litura Fabricius (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) SlitCSP18 (Lin et al. 2018). In addition, the function of CSPs is related to the age, sex, and mating status in insects (Zhou et al. 2013, Xue et al. 2016).

The diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae), is a destructive pest that damages the quality and quantity of cruciferous vegetables worldwide. P. xylostella mainly relies on volatile compounds released by host plants to find food and oviposition sites (Pivnick et al. 1994). Olfactory recognition in insects requires the cooperation of various olfactory proteins. Silencing olfactory genes responsible for identifying signals affects the feeding and mating behaviors of insects, thereby efficiently controlling the pest population (Pitino et al. 2011). Thus, identification and functional characterization of olfactory genes are of significant importance. In P. xylostella, a total of 118 olfactory genes, including 54 ORs, 16 IRs, 7 gustatory receptors (GRs), 15 CSPs, 24 OBPs, and 2 SNMPs, have been identified from antennal transcriptome (Yang et al. 2017). PxylCSP1 and PxylCSP2 have a high expression in the antennae of both male and female adults, while PxylCSP3 and PxylCSP4 are distributed in various tissues (Liu et al. 2010b). At present, only the binding characteristic of PxylCSP1 has been deeply studied. The protein has a binding specificity to Rhodojaponin-III (R-III), a nonvolatile oviposition inhibitor (Liu et al. 2010b). However, limited information has been focused on functions of other CSPs in diamondback moth.

We have detected the tissue expression profiles of some CSPs in P. xylostella (unpublished data), and the results show that PxylCSP11 is highly expressed in the antennae of the male and female moth, indicating its potential olfactory function. In order to better understand the function of PxylCSP11 in the olfactory communication system, we analyzed characteristics of PxylCSP11 sequence, constructed the recombinant expression vector of PxylCSP11 in a prokaryotic expression system, and tested the binding affinities of PxylCSP11 to volatile molecules through the fluorescence competitive binding assays. Our study enriches the understanding in functions of CSPs from P. xylostella and complex olfactory mechanisms in insects.

Materials and Methods

Insects Rearing and Tissue Collection

P. xylostella was reared in the Insect Neuroethology and Sensory Biology Laboratory, Shanxi Agricultural University and was maintained under constant conditions of 25 ± 1°C, 75% relative humidity, and a 14:10 (L:D) h photoperiod. For collecting various tissues, we dissected 300, 50, 30, 30, 100, and 100 3-day-old adults for antennae, heads without antennae, thoraxes, abdomens, legs, and wings, respectively. The adults were classified into two groups by sex. There were 12 tissue samples with three biological replicates. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA of different tissue samples was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Sangon, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The integrity of the extracted RNA was detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the purity was examined by the Ultra low volume spectrometer (BioDrop, United Kingdom). The first strand of cDNA was synthesized from total RNA (1 μg) using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (Takara, Dalian, China), and was used for PCR and qRT-PCR.

cDNA Cloning and Sequence Analysis

We obtained the sequence of PxylCSP11 (Accession no. XM_011564896.1) from the transcriptional data of P. xylostella submitted by NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/?term=txid51655[orgn]), and validated the nucleotide sequence of the gene by PCR. PCR assays were performed in a mixture of 25 μl containing 2 μl of antennae cDNA (100 ng), 12.5 μl of 2×Taq PCR Mastermix (Tiangen, Beijing, China), 1 μl of each primer (10 μM), and 8.5 μl of sterilized ddH2O. The PCR amplification procedure was as follows: predenaturation at 95°C for 1 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 48°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min; and final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR product was visualized by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The target gene was recovered, and ligated into T-Vector pMDTM 19 (Simple) (Takara). The recombinant T-Vector was transformed into E. coli (DH5α) competent cells (Takara), and sequenced with standard M13 primers. The obtained sequence was used to analyze basic characteristics of PxylCSP11. The open reading frame (ORF) of PxylCSP11 was found by utilizing the ORF Finder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html) (Min et al. 2005). The signal peptide of PxylCSP11 was predicted by SignalP 5.0 Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) (Almagro Armenteros et al. 2019). Molecular weight (MW) and isoelectric point (pI) were computed through the ExPASy ProtParam tool (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/). Multiple sequence alignment was produced with DNAMAN (Lynnon Biosoft, USA). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA7.0 based on the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates (Hall 2013).

qRT-PCR Analysis

The qRT-PCR assay was performed with the Bio-Rad CFX Connect Real-Time Detection System (USA). Ribosomal protein S4 (RPS4, GenBank XM_011555372) was used as an endogenous gene. The specificity of each primer pair was validated by melting curve analysis, and the efficiency was calculated by analyzing standard curves with a fivefold cDNA dilution series. In the experiment, the amplification efficiencies of all primers were 90–110%. The qRT-PCR assay was conducted in a 20 μl mixture containing 10 μl of 2× SG Fast qPCR Master Mix (Sangon), 0.4 μl of each primer (10 μM), 2 μl of sample cDNA, and 7.2 μl of sterilized ddH2O. The procedure of qRT-PCR reaction was as follows: denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 58°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 30 s; and melting curve analysis from 60 to 95°C. Three biological replicates and three technical replicates were performed for each tested sample. The expression level in different tissues was calculated by the comparative 2-ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). All data were analyzed through a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test (P < 0.05) in SPSS Statistics 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Expression Vector Construction

PxylCSP11 sequence without signal peptide for prokaryotic expression vector construction was amplified by PCR with a forward primer containing a BamH I-restriction site and a reverse primer containing a Xho I-restriction site (listed in Supp Table 1 [online only]). The recovered target gene was ligated into the T-Vector pMDTM 19 (Simple), and the product was transformed into E. coli (DH5α) competent cells. After sequencing, the correct reconstructed T-Vector was digested with BamH I and Xho I at 30°C for 4 h. The purified fragment was ligated into the expression vector pET28a (+) (Novagen, Madison, WI) linearized with the same restriction enzymes, and transformed into E. coli (DH5α) competent cells. Positive clones were sequenced to verify whether the sequence was consistent with PxylCSP11. The confirmed recombinant plasmid was then transformed into chemically competent E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells, and the strains were sequenced. Correct strains were induced to express recombinant proteins.

Induction and Purification of Recombinant PxylCSP11

The PxylCSP11 recombinant protein was induced at 30°C for 4 h with a final concentration of 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Bacteria cells were collected by centrifugation at 8,000 g for 10 min, suspended in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), sonicated in ice, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) showed that recombinant PxylCSP11 was expressed mainly in the supernatant. Protein purification was accomplished by Ni-NTA Resin (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). Purified recombinant proteins were analyzed by 15% SDS–PAGE and dialyzed overnight with 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4).

Fluorescence Competitive Binding Assays

Fluorescence binding assays were performed with a 1 cm light path quartz cuvette on an RF-5301 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan). The slit widths of excitation and emission were 5 nm. The emission spectra of the fluorescent probe, 4,4’-dianilino-1,1’-binaphthyl-5,5’-sulfonate (Bis-ANS, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), were recorded from 400 to 580 nm with an excitation wavelength of 365 nm (Zhang et al. 2011, Hua et al. 2013). To measure the affinity of Bis-ANS to PxylCSP11, 1 µM protein in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) was titrated with 1 mM Bis-ANS to final concentrations ranging from 1 to 10 µM. The recorded fluorescence intensity at the maximum emission wavelength of 485 nm was linearized using the Scatchard equation (Sideris et al. 1992), and the dissociation constants for Bis-ANS were then calculated.

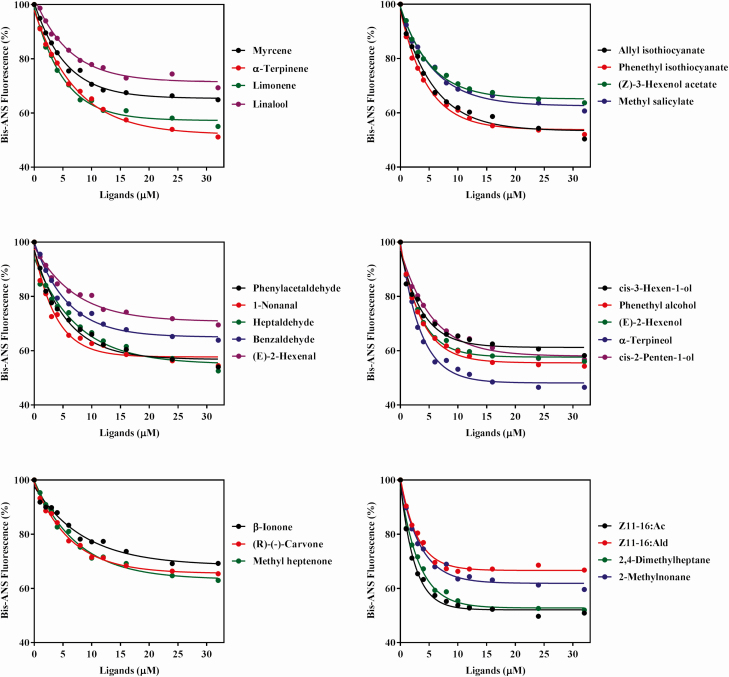

Twenty-five ligands, including host volatiles and two main sex pheromone components, (Z)-11-hexadecenyl acetate (Z11-16:Ac) and (Z)-11-hexadecenal (Z11-16:Ald), were used to detect the affinities of PxylCSP11. Ligands with concentrations ranging from 1 to 32 µM were added into the mixed solution of protein (1 μM) and probe (1 μM). All values were obtained from three independent measurements. The data were analyzed based on the assumption that the protein was 100% active with a stoichiometry of protein and ligand at a 1:1 ratio. Dissociation constants (Kd) of the competitor were calculated using the following equation: Kd = [IC50]/(1 + [Bis-ANS]/KBis-ANS, where [IC50] is the ligand’s concentration, [Bis-ANS] is the free concentration of Bis-ANS, and KBis-ANS is the dissociation constant of the complex of PxylCSP11 and Bis-ANS (Campanacci et al. 2001).

Results

Sequence Analysis of PxylCSP11

The cDNA sequence of PxylCSP11 contained a 369-bp ORF encoding 122 amino acid residues. At the N-terminus of the polypeptide chain, PxylCSP11 possessed a predicted 16-residue signal peptide. As the signal peptide was cleaved off, molecular weight of the mature protein PxylCSP11 was 12.34 kDa with an isoelectric point of 8.89. The results of multiple alignments showed that PxylCSP11 presented four conserved cysteines (Fig. 1), which formed two pairs of disulfide bonds. The sequence identity of PxylCSP11 with Spodoptera exigua Hübner (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) CSP11 was 87.10%. A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the amino acid sequences of P. xylostella and different insect orders, including Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Orthoptera, Hemiptera, and Hymenoptera (Fig. 2). The phylogenetic analysis showed that the CSPs of the same order were clustered in the same group and that PxylCSP11 was clearly located in the Lepidoptera group. PxylCSP11 and Lobesia botrana (Denis and Schiffermüller) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) LbotCSP16 shared the highest bootstrap support value of 100%, suggesting that these two proteins may be evolutionarily homologous.

Fig. 1.

Multiple alignments of PxylCSP11 and other CSPs from lepidopteran species. Conserved cysteine residues were labeled in red stars. The black, pink, and blue backgrounds indicated 100, 75, and 50% similarities, respectively. The Lepidoptera insects used for multiple sequence alignments were: Eogystia hippophaecolus (Hua et al.) (Lepidoptera: Cossidae) (EhipCSP, AOG12897.1), Heortia vitessoides Moore (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) (HvitCSP7, AZB49399.1), Ostrinia furnacalis Guenée (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) (OfurCSP13, BAV56817.1), L. botrana (LbotCSP10, AXF48709.1), Athetis dissimilis Hampson (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) (AdisCSP10, AND82452.1), Conogethes punctiferalis Guenée (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) (CpunCSP5, AHX37227.1), Operophtera brumata L. (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) (ObruCSP, KOB75936.1), Choristoneura fumiferana Clemens (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) (CfumCSP4, AAW23971.1), Ectropis obliqua Prout (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) (EoblCSP10, ALS03835.1), S. exigua (SexiCSP11, AKT26487.1), and Dendrolimus kikuchii Matsumura (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae) (DkikCSP, AII01028.1).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of PxylCSP11 with other CSPs from various insect orders. Different orders were marked as follows: Lepidoptera (red), Orthoptera (purple), Coleoptera (green), Hemiptera (yellow), Hymenoptera (blue). Lepidoptera insects included L. botrana (Lbot), C. medinalis (Cmed), Helicoverpa armigera Hübner (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) (Harm), O. furnacalis (Ofur), and Ectropis oblique Warren (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) (Eobl); Orthoptera insects included Oedaleus asiaticus (Bey-Bienko) (Orthoptera: Acrididae) (Oasi); Coleoptera insects included Tribolium castaneum Herbst (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) (Tcas) and Tenebrio molitor L. (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae); Hemiptera insects included Adelphocoris lineolatus (Alin) and Myzus persicae Sulzer (Homoptera: Aphididae) (Mper); Hymenoptera insects included Meteorus pulchricornis Wesmael (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) (Mpul), Microplitis mediator Haliday (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) (Mmed), A. mellifera (Amel), and Apis cerana cerana (Acer) Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Accession no. of CSPs for constructing phylogentic tree are in Supp. Table 2 (online only).

Tissue Expression Patterns of PxylCSP11

To better understand the function of PxylCSP11, we examined its expression pattern in different tissues by qRT-PCR. PxylCSP11 had a broad expression profile in all tissues of male and female moths, but it was predominantly expressed in antennae (Fig. 3). The expression level of PxylCSP11 in male antennae was higher than that in female antennae. Additionally, its expression was evident in the male moth abdomen. The expression of PxylCSP11 in other tissues was low, and there was no significant difference.

Fig. 3.

Tissue expression patterns of PxylCSP11 in the male and female Plutella xylostella by qRT-PCR. Various tissues included antennae, heads without antennae, thoraxes, abdomens, legs, and wings of male and female P. xylostella. Lower letters above each error bar showed significant differences in various tissues analyzed by using Turkey’s HSD method (P < 0.05).

Purification of the Recombinant Protein

After the PxylCSP11 cDNA was cloned into the pET28a (+) prokaryotic expression vector, the PxylCSP11 recombinant protein was induced to express in E. coli BL21 (DE3) strains. The induced recombinant PxylCSP11 was confirmed by 15% SDS–PAGE (Fig. 4A). The target protein mainly existed in the supernatant after bacterial lysis by ultrasonication (Fig. 4A). Proteins were subsequently purified using ProteinIso Ni-NTA Resin. Figure 4B shows the SDS–PAGE analysis indicated a single protein band of approximately 17 kDa, which is consistent with the predicted recombinant protein molecular weight. The purified recombinant proteins were used for fluorescent competitive binding assays.

Fig. 4.

Expression and purification of PxylCSP11 recombinant protein analyzed by SDS–PAGE. M: protein molecular weight marker. (A) Lane 1: non-induced PxylCSP11/pET28a (+); Lane 2: the crude bacterial extracts after induction by 1 mM IPTG; Lane 3: the supernatant of crude bacterial extracts after the induction; (B) Lane 1: the purified PxylCSP11 recombinant protein.

Binding Properties of Recombinant PxylCSP11

For analysis of the PxylCSP11 binding affinity, Bis-ANS was used as a competitive fluorescent reporter. When Bis-ANS was added dropwise to the protein solution, the maximum emission peak at 418 nm was shifted to approximately 485 nm. The Kd of Bis-ANS to PxylCSP11 was 1.98 ± 0.09 µM as calculated using the Scatchard equation (Fig. 5). The competitive binding curves of PxylCSP11 to various ligands are shown in Fig. 6. The IC50 values and Kd of PxylCSP11 to different ligands were then calculated (Table 1). In all tested volatiles, PxylCSP11 showed strong binding abilities to two special volatiles of cruciferous vegetables, namely, phenethyl isothiocyanate (19.53 µM) and allyl isothiocyanate (19.79 µM). PxylCSP11 also exhibited strong binding affinities to several other volatiles, including α-terpineol (10.69 µM), 2,4-dimethylheptane (16.34 µM), α-terpinene (20.19 µM), phenethyl alcohol (21.00 µM). In addition, PxylCSP11 had a high binding affinity for Z11-16:Ac (13.80 µM), which is one of the major sex pheromone components of P. xylostella.

Fig. 5.

Binding curve of Bis-ANS to PxylCSP11 and relative Scatchard plot analysis.

Fig. 6.

Competitive binding curves of PxylCSP11 with different volatile ligands.

Table 1.

Different affinity of PxylCSP11 with different volatile ligands

| Ligands | CSA No. | Company | Purity% | IC50 (μM) | Kd (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant volatiles a | |||||

| Monoterpenes | |||||

| Myrcene | 123-35-3 | Sigma–Aldrich | 90 | >32 | — |

| α-Terpinene | 99-86-5 | Sigma–Aldrich | 95 | 28.79 | 20.19 |

| (S)-(-)-Limonene | 5989-54-8 | Sigma–Aldrich | 95 | >32 | — |

| Linalool | 78-70-6 | Sigma–Aldrich | 97 | >32 | — |

| Esters | |||||

| Allyl isothiocyanate | 57-06-7 | Sigma–Aldrich | 95 | 27.99 | 19.79 |

| Phenethyl Isothiocyanate | 2257-09-2 | Sigma–Aldrich | 99 | 27.57 | 19.53 |

| (Z)-3-Hexenol acetate | 3681-71-8 | Sigma–Aldrich | 98 | >32 | — |

| Methyl salicylate | 119-36-8 | Sigma–Aldrich | 99 | >32 | — |

| Aldehydes | |||||

| Phenylacetaldehyde | 122-78-1 | Sigma–Aldrich | 95 | >32 | — |

| 1-Nonanal | 124-19-6 | Sigma–Aldrich | 95 | >32 | — |

| Heptaldehyde | 111-71-7 | Sigma–Aldrich | 95 | >32 | — |

| Benzaldehyde | 100-52-7 | Sigma–Aldrich | 98 | >32 | — |

| (E)-2-Hexenal | 6728-26-3 | Sigma–Aldrich | 98 | >32 | — |

| Alcohols | |||||

| (Z)-2-Penten-1-ol | 1576-95-0 | Sigma–Aldrich | 95 | >32 | — |

| (Z)-3-Hexen-1-ol | 928-96-1 | Sigma–Aldrich | 98 | >32 | — |

| Phenethyl alcohol | 60-12-8 | Sigma–Aldrich | 99 | 29.84 | 21.00 |

| (E)-2-Hexenol | 928-95-0 | Sigma–Aldrich | 95 | >32 | — |

| α-Terpineol | 98-55-5 | Sigma–Aldrich | 96 | 15.14 | 10.69 |

| Ketones | |||||

| β-Ionone | 79-77-6 | Sigma–Aldrich | 96 | >32 | — |

| (R)-(-)-Carvone | 6485-40-1 | Sigma–Aldrich | 99 | >32 | — |

| Methyl heptenone | 110-93-0 | Sigma–Aldrich | 98 | >32 | — |

| Alkanes | |||||

| 2,4-Dimethylheptane | 2213-23-2 | Aladdin | 98 | 23.12 | 16.34 |

| 2-Methylnonane | 871-83-0 | Sigma–Aldrich | 98.5 | >32 | — |

| Sex pheromone components from Plutella xylostella | |||||

| Z11-16:Ac | 34010-21-4 | Shin-Etsu | >95% | 19.63 | 13.80 |

| Z11-16:Ald | 53939-28-9 | Shin-Etsu | >95% | >32 | — |

For IC50 values more than 32 μM, the corresponding Kd values are not calculated and was represent by ‘—’.

a2,4-Dimethylheptane was from Mentha haplocalyx (a non-host plant of Plutella xylostella) in our previous work (unpublished data). The other plant volatiles were detected in cruciferous vegetables, including Brassica oleracea, Brassica campestris, and Brassica rapa (Blaakmeer et al. 1994, Geervliet et al. 1997, Ômura et al. 1999, Reddy et al. 2002, Bukovinszky et al. 2005).

Discussion

In this study, we cloned and sequenced the PxylCSP11 cDNA from P. xylostella and analyzed the properties of PxylCSP11 protein. The PxylCSP11 from P. xylostella possesses four conserved cysteines, which are common in a typical CSP. The low molecular, N-terminal signal peptide and two disulfide bridges of PxylCSP11 also represent the common characteristics of insect CSPs (Angeli et al. 1999, Zhang and Lei 2015, Ali et al. 2019). Generally, insect CSPs are highly conserved in evolution, and their sequence identifies are between 40 and 50% even among different insect orders (Wanner et al. 2004, Pelosi et al. 2006, Zhu et al. 2016). Our results showed that the sequence identity of PxylCSP11 and other Lepidoptera CSPs was as high as 80% and that PxylCSP11 was clustered with lepidopterous CSPs in a group according to the phylogenetic tree, indicating the conservation of CSP evolution in insects. As the bootstrap support value of PxylCSP11 and L. botrana LbotCSP16 reached 100%, two proteins might come from a close ancestor. We speculated that PxylCSP11 and LbotCSP16 have similar functions. LbotCSP16 was expressed in antennae of male and female moths (Rojas et al. 2018). However, there are no reports on the function of LbotCSP16.

The expression of CSPs in various tissues is closely related to their functions (Gu et al. 2012, Yang et al. 2014). Increasing studies show that CSPs highly expressed in antennae participate in olfactory recognition (Khuhro et al. 2018, Wu et al. 2019, Zhang et al. 2020). In our study, the result that PxylCSP11 was highly expressed in antenna of male and female adults suggested that PxylCSP11 may be involved in olfactory perception. It has been shown that CSPs with high expression in the antennae can recognize host volatiles (Zhang et al. 2013, He et al. 2017, Chen et al. 2018). M. alternatus MaltCSP5 is mainly expressed in male and female antennae, and the protein has a high binding affinity to most pine volatiles (Ali et al. 2019). An antenna-enriched CmedCSP33 protein in Cnaphalocrocis medinalis Guenée (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) exhibites strong binding abilities to seven compounds of rice volatiles (Duan et al. 2019). Based on the above-mentioned study, the antennae-predominant PxylCSP11 may be responsible for binding host volatiles in olfactory recognition.

Interestingly, the expression of PxylCSP11 in antennae of males was higher than that in antennae of females, which was similar to the expression profiles of other insect CSPs, including SinfCSP19 of Sesamia inferens Walker (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) (Zhang et al. 2014), SexiCSP3 of S. exigua (Zhu et al. 2015) and MaltCSP5 of M. alternatus (Ali et al. 2019). The male-biased SinfCSP19 has strong binding abilities to three sex pheromones released from females (Zhang et al. 2014). Unlike female insects, which need to seek host plants for surviving and oviposition, males are less dependent on host plants. The main task of male adults is to locate sexual partners for mating in their life (Pivnick et al. 1990, Bonduriansky 2001, Reddy and Guerrero 2004). These complex physiological activities are also reflected in the difference of perception of host volatiles and sex pheromones of males and females. It is common that electroantennogram (EAG) responses to sex pheromone components are stronger in males than in females but weaker to host volatiles. In P. xylostella, the response of males to sex pheromone constituents is higher than to host plant odorants, but females have a higher EAG response to plant odorants than to sex pheromones (Palaniswamy et al. 1986, Pivnick et al. 1994, Wu et al. 2020). Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that PxylCSP11 may be sensitive to the sex pheromone besides plant volatiles in the olfactory communication.

In addition, PxylCSP11 was also highly expressed in male abdomen. Although the function of CSPs in the abdomen is not completely clear, it has been confirmed that CSPs are expressed in this tissue in other insects. For example, B. mori BmorCSP6, BmorCSP9, BmorCSP11, and BmorCSP14 are expressed in the pheromone gland, and BmorCSP11 and BmorCSP13 are strictly limited in the spermary (Gong et al. 2007). More importantly, L.migratoria LmigCSP91, which is abundant in the reproductive organs of male locusts, participates in the transmission of pheromones during mating (Zhou et al. 2013). Additionally, the low expression of PxylCSP11 in other tissues does not exclude other potential unknown functions of the protein.

The premise that CSPs possess olfactory recognition function is that the proteins recognize and bind semiochemicals released from host plants and intraspecific or interspecific insects. Therefore, we investigated if PxylCSP11 binds to chemical cues by fluorescence competitive binding assays. The results showed that PxylCSP11 had strong binding affinities to several chemicals, including Z11-16:Ac, α-terpineol, phenethyl isothiocyanate, allyl isothiocyanate, α-terpinene, phenethyl alcohol, and 2,4-dimethylheptane. Among these chemicals, Z11-16:Ac is one of the major sex pheromone components of P. xylostella, α-terpineol, phenethyl isothiocyanate, allyl isothiocyanate, α-terpinene, and phenethyl alcohol are cruciferae plant volatiles, and 2,4-dimethylheptane is released from non-host plants. The binding of PxylCSP11 to Z11-16:Ac supported the above hypothesis that PxylCSP11 was sensitive to the sex pheromone. Over decades, the management strategies based on sex pheromones of P. xylostella in the agronomy practices can lure the male moths and reduce the mating rate of the adults, thereby effectively controlling the damage of P. xylostella (Reddy and Guerrero 2000b, Li et al. 2012, Wu et al. 2012). Although PBPs (pheromone binding proteins) are as the transporters of sex pheromones, there are some reports on binding properties of CSPs to sex pheromones in various insect species recently. In C. medinalis, CmedCSP3 has a binding affinity to Z11-16:Ac, one of the major sex pheromones of C. medinalis, and the EAG response of the insect to Z11-16:Ac is decreased when the CmedCSP3 gene is silenced by RNAi (Zeng et al. 2018a). PxylCSP11 showed a binding specificity to the sex pheromone, suggesting the protein may function in courtship and mating.

The preference of herbivorous insects for plants is determined by host volatiles. Therefore, the volatiles of cruciferae plants play an inevitable role in the life activities of P. xylostella. Allyl isothiocyanate and phenethyl isothiocyanate are special volatiles of cruciferous vegetables, which are from the glucosinolates by hydrolysis (Reddy and Guerrero 2000a, Bones and Rossiter 2006, Tian et al. 2018). Allyl isothiocyanate is an attractant to P. xylostella, which lures the moth to foraging and oviposition (Griffiths et al. 2001, Renwick et al. 2006, Dai et al. 2008, Tian et al. 2018). Thus, PxylCSP11 may involve in the behavior of P. xylostella to find cruciferous plants in some way. Previous studies have reported that an antennal binding protein (PxylABP, accession no. AB189031.1) has the ability to bind allyl isothiocyanate (Kd = 0.91) (Deng et al. 2016). The binding and transportation of the same ligands seem to be performed by different types of proteins to ensure the high efficiency of olfactory recognition. As an example, PBPs usually are the carrier proteins of sex pheromones, while GOBPs (general odorant binding proteins) and CSPs also have abilities to bind sex pheromones (Zhou et al. 2009, Zhang et al. 2014). Alpha-terpinene released from cruciferae plants (Geervliet et al. 1997) has an effect on feeding and oviposition of P. xylostella (Zhang et al. 2004). Our results showed that PxylCSP11 has a strong binding affinity to α-terpinene. Meanwhile, PxylCSP11 showed a binding activity towards α-terpineol. Alpha-terpineol is similar to α-terpinene in structure, both of which have a six-carbon ring with a double bond. It has been reported that the binding of CSPs to ligands depends on the interaction between the functional atoms of ligands and the amino acids of CSPs (Tan et al. 2018, Younas et al. 2018). Therefore, the binding of PxylCSP11 to these two chemicals may be accomplished through similar binding sites in its active binding cavity. Phenethyl alcohol, a binding ligand of PxylCSP11, is an aromatic compound, which is commonly present in various plants such as Brassicaceae species (Ômura et al. 1999). The chemical can cause EAG responses and attraction behaviors of some lepidopterous insects (Honda et al. 1998). In addition, phenylethanol is also found in the hairpencils of male moths, such as Mamestra brassicae L. (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) (Jacquin et al. 1991) and Mamsetra configurata Walker (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) (Clearwater 1975). When the male moth mates with the female of the same species, the hairpencils of the male will release some volatiles (e.g., phenethyl alcohol). The chemicals may inhibit the release of sex pheromones by the female, and prevent other males from interfering with mating process (Huang et al. 2015). PxylCPS11 showed similar levels of sensitivities to the sex pheromone component and plant volatiles, suggesting that PxylCPS11 plays important roles not only for mating but also for host plant finding in the olfactory communication system.

2,4-dimethylheptane is another binding ligand of PxylCSP11. To date, the compound has been reported to exist in Sims (Parietales: Passifloraceae) (Liu et al. 2010a) and Ambrosia trifida L. (Campanulales: Asteraceae) (Wang and Zhu 1996), non-host plants of P. xylostella. In our previous work, 2,4-dimethylheptane was identified from Mentha haplocalyx Briq. (Lamiales: Labiatae), a repellent plant against P. xylostella, by GC-EAD with electrophysiological activity to P. xylostella, and the compound was a repellent of the moth investigated by the Y-tube olfactometer (unpublished data). PxylCSP11 has a binding affinity to 2,4-dimethylheptane, suggesting that PxylCSP11 may mediate P. xylostella to distinguish the non-hosts and host plants from the complex environment, and tune the corresponding physiological or behavioral responses of P. xylostella.

In conclusion, our results showed that PxylCSP11 mainly expressed in the antennae of male and female adults and that PxylCSP11 mainly had an affinity to host volatiles and Z11-16:Ac. Therefore, PxylCSP11 may play a dual role in the perception of host volatiles and the sex pheromone in the olfactory recognition of P. xylostella. The characterization and function of PxylCSP11 from P. xylostella contribute to understanding the underlying mechanisms of the complex olfactory communication in insects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shanxi, China (201801D121250 and 201901D111231), and Scientific Research Foundation of Shanxi Agricultural University (2014ZZ08).

References Cited

- Abuin L, Bargeton B, Ulbrich M H, Isacoff E Y, Kellenberger S, and Benton R. . 2011. Functional architecture of olfactory ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron. 69: 44–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S, Ahmed M Z, Li N, Ali S A I, and Wang M Q. . 2019. Functional characteristics of chemosensory proteins in the sawyer beetle Monochamus alternatus Hope. Bull. Entomol. Res. 109: 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almagro Armenteros J J, Tsirigos K D, Sønderby C K, Petersen T N, Winther O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, and Nielsen H. . 2019. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 37: 420–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammagarahalli B, and Gemeno C. . 2014. Response profile of pheromone receptor neurons in male Grapholita molesta (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). J. Insect Physiol. 71: 128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angeli S, Ceron F, Scaloni A, Monti M, Monteforti G, Minnocci A, Petacchi R, and Pelosi P. . 1999. Purification, structural characterization, cloning and immunocytochemical localization of chemoreception proteins from Schistocerca gregaria. Eur. J. Biochem. 262: 745–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura G, Matsui K, and Takabayashi J. . 2009. Chemical and molecular ecology of herbivore-induced plant volatiles: proximate factors and their ultimate functions. Plant Cell Physiol. 50: 911–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaakmeer A, Geervliet J B F, Loon J J A, Posthumus M A, Beek T A, and Groot A. . 1994. Comparative headspace analysis of cabbage plants damaged by two species of Pieris caterpillars: consequences for in-flight host location by Cotesia parasitoids. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 73: 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Bonduriansky R. 2001. The evolution of male mate choice in insects: a synthesis of ideas and evidence. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 76: 305–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bones A M, and Rossiter J T. . 2006. The enzymic and chemically induced decomposition of glucosinolates. Phytochemistry 67: 1053–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukovinszky T, Gols R, Posthumus M A, Vet L E, and Van Lenteren J C. . 2005. Variation in plant volatiles and attraction of the parasitoid Diadegma semiclausum (Hellén). J. Chem. Ecol. 31: 461–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanacci V, Krieger J, Bette S, Sturgis J N, Lartigue A, Cambillau C, Breer H, and Tegoni M. . 2001. Revisiting the specificity of Mamestra brassicae and Antheraea polyphemus pheromone-binding proteins with a fluorescence binding assay. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 20078–20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G L, Pan Y F, Ma Y F, Wang J, He M, and He P. . 2018. Binding affinity characterization of an antennae-enriched chemosensory protein from the white-backed planthopper, Sogatella furcifera (Horvath), with host plant volatiles. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 152: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clearwater J R. 1975. Pheromone metabolism in male Pseudaletia separata (Walk.) and Mamsetra configurata (Walk.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 50: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J Q, Deng J Y, and Du J W. . 2008. Development of bisexual attractants for diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) based on sex pheromone and host volatiles. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 43: 631–638. [Google Scholar]

- Deng P, Yuan W, Li Y, Wang L, and Li C. . 2016. Study on binding pattern of antennal binding protein PxylABP in Plutella xylostella. Acta Agricultural Boreali Sinica 31: 233–238. (Chin: Hebei Nongxuebao) [Google Scholar]

- Duan S G, Li D Z, and Wang M Q. . 2019. Chemosensory proteins used as target for screening behaviourally active compounds in the rice pest Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Insect Mol. Biol. 28: 123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faucheux M J, Hamidi R, Mercadal M, Thomas M, and Frerot B. . 2019. Antennal sensilla of male and female of the nut weevil, Curculio nucum Linnaeus, 1758 (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Ann. Soc. Entomol. Fr. 55: 395–409. [Google Scholar]

- Field L M, Pickett J A, and Wadhams L J. . 2000. Molecular studies in insect olfaction. Insect Mol. Biol. 9: 545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer J, Pregitzer P, Breer H, and Krieger J. . 2018. Access to the odor world: olfactory receptors and their role for signal transduction in insects. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75: 485–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forêt S, Wanner K W, and Maleszka R. . 2007. Chemosensory proteins in the honey bee: insights from the annotated genome, comparative analyses and expressional profiling. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37: 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geervliet J B F, Posthumus M A, Vet L E M, and Dicke M. . 1997. Comparative analysis of headspace volatiles from different caterpillar-infested or uninfested food plants of Pieris species. J. Chem. Ecol. 23: 2935–2954. [Google Scholar]

- Gong D P, Zhang H J, Zhao P, Lin Y, Xia Q Y, and Xiang Z H. . 2007. Identification and expression pattern of the chemosensory protein gene family in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37: 266–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths D W, Deighton N, Birch A N, Patrian B, Baur R, and Städler E. . 2001. Identification of glucosinolates on the leaf surface of plants from the Cruciferae and other closely related species. Phytochemistry 57: 693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S H, Wang S Y, Zhang X Y, Ji P, Liu J T, Wang G R, Wu K M, Guo Y Y, Zhou J J, and Zhang Y J. . 2012. Functional characterizations of chemosensory proteins of the alfalfa plant bug Adelphocoris lineolatus indicate their involvement in host recognition. PLoS One 7: e42871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall B G. 2013. Building phylogenetic trees from molecular data with MEGA. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30: 1229–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson B S, and Stensmyr M C. . 2011. Evolution of insect olfaction. Neuron. 72: 698–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanali A, Njagi P G, and Bashir M O. . 2005. Chemical ecology of locusts and related acridids. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 50: 223–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He P, Li Z Q, Zhang Y F, Chen L, Wang J, Xu L, Zhang Y N, and He M. . 2017. Identification of odorant-binding and chemosensory protein genes and the ligand affinity of two of the encoded proteins suggest a complex olfactory perception system in Periplaneta americana. Insect Mol. Biol. 26: 687–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K, ÔMura H, and Hayashi N. . 1998. Identification of floral volatiles from Ligustrum japonicum that stimulate flower-visiting by cabbage butterfly, Pieris rapae. J. Chem. Ecol. 24: 2167–2180. [Google Scholar]

- Hua J F, Zhang S, Cui J J, Wang D J, Wang C Y, Luo J Y, Lv L M, and Ma Y. . 2013. Functional characterizations of one odorant binding protein and three chemosensory proteins from Apolygus lucorum (Meyer-Dur) (Hemiptera: Miridae) legs. J. Insect Physiol. 59: 690–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C F, You X F, Wang J, Li W Z, and Yan F M. . 2015. Antennal responses of the cabbage butterfly, Pieris rapae, to some common volatiles of Brassicaceae and a long-term field trapping based on uniform mixture design. J. Environ. Entomol. 37: 1219–1226. (Chin: Huanjing Kunchong Xuebao) [Google Scholar]

- Jacquin E, Nagnan P, and Frerot B. . 1991. Identification of hairpencil secretion from male Mamestra brassicae (L.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and electroantennogram studies. J. Chem. Ecol. 17: 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Brandazza A, Navarrini A, Ban L, Zhang S, Steinbrecht R A, Zhang L, and Pelosi P. . 2005. Expression and immunolocalisation of odorant-binding and chemosensory proteins in locusts. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62: 1156–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaissling K E. 2001. Olfactory perireceptor and receptor events in moths: a kinetic model. Chem. Senses 26: 125–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaissling K E. 2009. Olfactory perireceptor and receptor events in moths: a kinetic model revised. J. Comp. Physiol. A. Neuroethol. Sens. Neural. Behav. Physiol. 195: 895–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khuhro S A, Yan Q, Liao H, Zhu G H, Sun J B, and Dong S L. . 2018. Expression profile and functional characterization suggesting the involvement of three chemosensory proteins in perception of host plant volatiles in Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). J. Insect Sci. 18: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitabayashi A N, Arai T, Kubo T, and Natori S. . 1998. Molecular cloning of cDNA for p10, a novel protein that increases in the regenerating legs of Periplaneta americana (American cockroach). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 28: 785–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal W S. 2013. Odorant reception in insects: roles of receptors, binding proteins, and degrading enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58: 373–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Wang P, Zhang L, Xu X, Cao Z, and Zhang L. . 2018. Expressions of olfactory proteins in locust olfactory organs and a palp odorant receptor involved in plant aldehydes detection. Front. Physiol. 9: 663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P Y, Zhu J W, and Qin Y C. . 2012. Enhanced attraction of Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) to pheromone-baited traps with the addition of green leaf volatiles. J. Econ. Entomol. 105: 1149–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X D, Mao Y W, and Zhang L. . 2018. Binding properties of four antennae-expressed chemosensory proteins (CSPs) with insecticides indicates the adaption of Spodoptera litura to environment. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 146: 43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H X, Huang C S, Lin S, and Sun Z J. . 2010a. Extraction of volatile oil from Passiflora edulis Sims seed. China Brew. 29: 150–153. (Chin: Zhongguo Niangzao) [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Luo Q, Zhong G, Rizwan-Ul-Haq M, and Hu M. . 2010b. Molecular characterization and expression pattern of four chemosensory proteins from diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). J. Biochem. 148: 189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K J, and Schmittgen T D. . 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25: 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleszka R, and Stange G. . 1997. Molecular cloning, by a novel approach, of a cDNA encoding a putative olfactory protein in the labial palps of the moth Cactoblastis cactorum. Gene. 202: 39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleszka J, Forêt S, Saint R, and Maleszka R. . 2007. RNAi-induced phenotypes suggest a novel role for a chemosensory protein CSP5 in the development of embryonic integument in the honeybee (Apis mellifera). Dev. Genes Evol. 217: 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchese S, Angeli S, Andolfo A, Scaloni A, Brandazza A, Mazza M, Picimbon J, Leal W S, and Pelosi P. . 2000. Soluble proteins from chemosensory organs of Eurycantha calcarata (Insects, Phasmatodea). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 30: 1091–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna M P, Hekmat-Scafe D S, Gaines P, and Carlson J R. . 1994. Putative Drosophila pheromone-binding proteins expressed in a subregion of the olfactory system. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 16340–16347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min X J, Butler G, Storms R, and Tsang A. . 2005. OrfPredictor: predicting protein-coding regions in EST-derived sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 33: W677–W680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ômura H, Honda K, and Hayashi N. . 1999. Chemical and chromatic bases for preferential visiting by the cabbage butterfly, Pieris rapae, to rape flowers. J. Chem. Ecol. 25: 1895–1906. [Google Scholar]

- Palaniswamy P, Gillott C, and Slater G P. . 1986. Attraction of diamondback moths, Plutella xylostella (L.) (Lepidoptera, Plutellidae), by volatile compounds of canola, white mustard and faba bean. Can. Entomol. 118: 1279–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi P, Iovinella I, Zhu J, Wang G, and Dani F R. . 2018. Beyond chemoreception: diverse tasks of soluble olfactory proteins in insects. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 93: 184–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi P, Zhou J J, Ban L P, and Calvello M. . 2006. Soluble proteins in insect chemical communication. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63: 1658–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitino M, Coleman A D, Maffei M E, Ridout C J, and Hogenhout S A. . 2011. Silencing of aphid genes by dsRNA feeding from plants. PLoS One 6: e25709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivnick K A, Jarvis B J, and Slater G P. . 1994. Identification of olfactory cues used in host-plant finding by diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 20: 1407–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivnick K A, Jarvis B J, Slater G P, Gillott C, and Underhill E W. . 1990. Attraction of the diamondback moth (Lepidoptera, Plutellidae) to volatiles of oriental mustard-the influence of age, sex, and prior exposure to mates and host plants. Environ. Entomol. 19: 704–709. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G V P, and Guerrero A. . 2000a. Behavioral responses of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella, to green leaf volatiles of Brassica oleracea subsp. capitata. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48: 6025–6029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G V P, and Guerrero A. . 2000b. Pheromone-based integrated pest management to control the diamondback moth Plutella xylostella in cabbage fields. Pest Manage. Sci. 56: 882–888. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G V P, and Guerrero A. . 2004. Interactions of insect pheromones and plant semiochemicals. Trends Plant Sci. 9: 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G V, Holopainen J K, and Guerrero A. . 2002. Olfactory responses of Plutella xylostella natural enemies to host pheromone, larval frass, and green leaf cabbage volatiles. J. Chem. Ecol. 28: 131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renwick J A, Haribal M, Gouinguené S, and Städler E. . 2006. Isothiocyanates stimulating oviposition by the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella. J. Chem. Ecol. 32: 755–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson H M, Martos R, Sears C R, Todres E Z, Walden K K, and Nardi J B. . 1999. Diversity of odourant binding proteins revealed by an expressed sequence tag project on male Manduca sexta moth antennae. Insect Mol. Biol. 8: 501–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas V, Jiménez H, Palma-Millanao R, González-González A, Machuca J, Godoy R, Ceballos R, Mutis A, and Venthur H. . 2018. Analysis of the grapevine moth Lobesia botrana antennal transcriptome and expression of odorant-binding and chemosensory proteins. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D. Genom. Proteom. 27: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sideris E E, Valsami G N, Koupparis M A, and Macheras P E. . 1992. Determination of association constants in cyclodextrin/drug complexation using the Scatchard plot: application to beta-cyclodextrin-anilinonaphthalenesulfonates. Pharm. Res. 9: 1568–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H Z, Song Y Q, Du J, Wang X D, and Cheng Z J. . 2016. Identification and tissue distribution of chemosensory protein and odorant binding protein genes in Athetis dissimilis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 51: 409–420. [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Song X, Fu X, Wu F, Hu F, and Li H. . 2018. Combinatorial multispectral, thermodynamics, docking and site-directed mutagenesis reveal the cognitive characteristics of honey bee chemosensory protein to plant semiochemical. Spectrochim. Acta. A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 201: 346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H J, Shuo L, Yong C, Chen Y X, Zhao J W, Gu X J, and Hui W. . 2018. Electroantennogram responses to plant volatiles associated with fenvalerate resistance in the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 111: 1354–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt R G, Miller N E, Litvack R, Fandino R A, Sparks J, Staples J, Friedman R, and Dickens J C. . 2009. The insect SNMP gene family. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39: 448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D L, and Zhu X R. . 1996. GC and GC/MS analysis of volatile of Ambrosia artemissifolia and A. trifida. J. Chin. Mass Spectrom. Soc. 17:37–41. (Chin: Zhipu Xuebao). [Google Scholar]

- Wanner K W, Willis L G, Theilmann D A, Isman M B, Feng Q, and Plettner E. . 2004. Analysis of the insect os-d-like gene family. J. Chem. Ecol. 30: 889–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z Z, Cui Y, Qu M Q, Lin J H, Chen M S, Bin S Y, and Lin J T. . 2019. Candidate genes coding for odorant binding proteins and chemosensory proteins identified from dissected antennae and mouthparts of the southern green stink bug Nezara viridula. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D. Genom. Proteom. 31: 100594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu A, Li X, Yan X, Fan W, and Hao C. . 2020. Electroantennogram responses of Plutella xylostella (L.), to sex pheromone components and host plant volatile semiochemicals. J. Appl. Entomol. 144: 396–406. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q J, Zhang S F, Yao J L, Xu B Y, Wang S L, and Zhang Y J. . 2012. Management of diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) by mating disruption. Insect Sci. 19: 643–648. [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Fan J, Zhang Y, Xu Q, Han Z, Sun J, and Chen J. . 2016. Identification and expression analysis of candidate odorant-binding protein and chemosensory protein genes by antennal transcriptome of Sitobion avenae. PLoS One 11: e0161839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X Z, Deng C P, Sun X J, and Hao C. . 2014. Effects of various degrees of antennal ablation on mating and oviposition preferences of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella L. J. Integr. Agric. 13: 1311–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Yan X Z, Deng C P, Xie J X, Wu L J, Sun X J, and Hao C. . 2017. Distribution patterns and morphology of sensilla on the antennae of Plutella xylostella (L.). A scanning and transmission electron microscopic study. Micron. 103: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S Y, Cao D P, Wang G R, and Liu Y. . 2017. Identification of genes involved in chemoreception in Plutella xyllostella by antennal transcriptome analysis. Sci. Rep. 7: 11941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, He P, and Dong S L. . 2014. Different expression profiles suggest functional differentiation among chemosensory proteins in Nilaparvata lugens (Hemiptera: Delphacidae). J. Insect Sci. 14: 270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younas A, Waris M I, Chang X Q, Shaaban M, Abdelnabby H, Ul Qamar M T, and Wang M Q. . 2018. A chemosensory protein MsepCSP5 involved in chemoreception of oriental armyworm Mythimna separata. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 14: 1935–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng F F, Liu H, Zhang A, Lu Z X, Leal W S, Abdelnabby H, and Wang M Q. . 2018a. Three chemosensory proteins from the rice leaf folder Cnaphalocrocis medinalis involved in host volatile and sex pheromone reception. Insect Mol. Biol. 27: 710–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Yang Y T, Wu Q J, Wang S L, Xie W, and Zhang Y J. . 2018b. Genome-wide analysis of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in the sweet potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci. Insect Sci. 26: 620–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z K, and Lei Z R. . 2015. Identification, expression profiling and fluorescence-based binding assays of a chemosensory protein gene from the Western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis. PLoS One 10: e0117726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Chen L Z, Gu S H, Cui J J, Gao X W, Zhang Y J, and Guo Y Y. . 2011. Binding characterization of recombinant odorant-binding proteins from the parasitic wasp, Microplitis mediator (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 37: 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Chen J L, Lin J H, Lin J T, and Wu Z Z. . 2020. Odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins potentially involved in host plant recognition in the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri. Pest Manag. Sci. 76: 2609–2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M X, Ling B, Chen S Y, Liang G W, and Pang X F. . 2004. Repellent and oviposition deterrent activities of the essential oil from Mikania micrantha and its compounds on Plutella xylostella. Insect Sci. 11: 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T T, Wang W X, Zhang Z D, Zhang Y J, and Guo Y Y. . 2013. Functional characteristics of a novel chemosensory protein in the cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner). J. Integr. Agric. 12: 853–861. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y N, Ye Z F, Yang K, and Dong S L. . 2014. Antenna-predominant and male-biased CSP19 of Sesamia inferens is able to bind the female sex pheromones and host plant volatiles. Gene. 536: 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J J, Robertson G, He X, Dufour S, Hooper A M, Pickett J A, Keep N H, and Field L M. . 2009. Characterisation of Bombyx mori odorant-binding proteins reveals that a general odorant-binding protein discriminates between sex pheromone components. J. Mol. Biol. 389: 529–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S H, Zhang J, Zhang S G, and Zhang L. . 2010. Expression of chemosensory proteins in hairs on wings of Locusta migratoria (Orthoptera: Acrididae). J. Appl. Entomol. 132: 439–450. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X H, Ban L P, Iovinella I, Zhao L J, Gao Q, Felicioli A, Sagona S, Pieraccini G, Pelosi P, Zhang L, . et al. 2013. Diversity, abundance, and sex-specific expression of chemosensory proteins in the reproductive organs of the locust Locusta migratoria manilensis. Biol. Chem. 394: 43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J Y, Ze S Z, and Yang B. . 2015. Identification and expression profiling of six chemosensory protein genes in the beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 18: 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Iovinella I, Dani F R, Liu Y L, Huang L Q, Liu Y, Wang C Z, Pelosi P, and Wang G. . 2016. Conserved chemosensory proteins in the proboscis and eyes of Lepidoptera. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 12: 1394–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.