Abstract

Small molecule inhibitors of calcium-dependent proteases, calpains (CAPNs), protect against neurodegeneration induced by a variety of insults including excitotoxicity and spinal cord injury (SCI). Many of these compounds, however, also inhibit other proteases, which has made it difficult to evaluate the contribution of calpains to neurodegeneration. Calpastatin is a highly specific endogenous inhibitor of classical calpains, including CAPN1 and CAPN2. In the present study, we utilized transgenic mice that overexpress human calpastatin under the prion promoter (PrP-hCAST) to evaluate the hypothesis that calpastatin overexpression protects against excitotoxic hippocampal injury and contusive SCI. The PrP-hCAST organotypic hippocampal slice cultures showed reduced neuronal death and reduced calpain-dependent proteolysis (α-spectrin breakdown production, 145 kDa) at 24 h after N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) injury compared with the wild-type (WT) cultures (n = 5, p < 0.05). The PrP-hCAST mice (n = 13) displayed a significant improvement in locomotor function at one and three weeks after contusive SCI compared with the WT controls (n = 9, p < 0.05). Histological assessment of lesion volume and tissue sparing, performed on the same animals used for behavioral analysis, revealed that calpastatin overexpression resulted in a 30% decrease in lesion volume (p < 0.05) and significant increases in tissue sparing, white matter sparing, and gray matter sparing at four weeks post-injury compared with WT animals. Calpastatin overexpression reduced α-spectrin breakdown by 51% at 24 h post-injury, compared with WT controls (p < 0.05, n = 3/group). These results provide support for the hypothesis that sustained calpain-dependent proteolysis contributes to pathological deficits after excitotoxic injury and traumatic SCI.

Keywords: calpastatin overexpression, hippocampal injury, spinal cord injury

Introduction

Traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) often results in permanent disability with a devastating impact on the patient's quality of life. The secondary injury cascade that follows the mechanical injury has numerous components, which include excitotoxic injury and excessive calpain activation.1–4 Calpain inhibition represents a viable therapeutic target after neurotrauma. Improvements obtained with small molecule calpain inhibitors have been modest, however.2,5–8 This is thought to be the result of the relatively weak potency, short half-life, and poor specificity of the small molecule calpain inhibitors and the sustained activation of calpains after SCI.1,9,10

Calpains 1 and 2 are composed of separate large subunit (CAPN1 and CAPN2) and a common small subunit (CAPNS1). The term calpain refers to the enzyme while the CAPN nomenclature refers to the individual subunits. There are fifteen calpain isoforms in mammals, which can be classified as classical and non-classical, or as conventional and unconventional based on their domain structure and subunit composition.11 Calpains 1 and 2 are referred to as both conventional calpains, containing a penta-EF hand domain, and as classical calpains, being heterodimers composed of a large and small subunit. In the mammalian central nervous system (CNS), calpain subunits include the classical/conventional calpains CAPN1/S1 and CAPN2/S1, as well as non-classical/unconventional calpains CAPN5, CAPN7, CAPN10, CAPN 15; and also unconventional/classical CAPN3 (mouse.brain-map.org)12; Of these, the classical calpains 1 and 2 are the most extensively studied because these were the first calpains discovered.13,14

Calpastatin is a highly specific and endogenous inhibitor of conventional calpains, binding to the EF hand domains of the conventional calpain subunits and positioning the inhibitory domain at the catalytic region of CAPN1 and CAPN2.15–17 Although calpastatin is present within neurons, the endogenous levels of calpastatin are unable to prevent fully the damaging and prolonged proteolytic activity of classical calpains after SCI.

In this study, increased calpastatin expression was achieved using transgenic mice that overexpress the human calpastatin (Prp-hCAST) construct under control of a calcium-calmodulin dependent kinase II α promoter. Based on the specificity of the endogenous inhibitor calpastatin to classical calpains, we therefore sought to determine whether calpastatin overexpression in the hCAST transgenic mouse model would protect against excitotoxic injury and against traumatic SCI. The PrP-hCAST mice are suitable for mechanistic studies, although pharmacological inhibitors of calpain with improved specificity are desired for therapeutic purposes.

Methods

Animals

Mice expressing human calpastatin (hCAST) under control of the prion promoter (PrP-hCAST) were maintained and genotyped as described previously.18 Thirty-five neonatal transgenic (Tg) Prp-hCAST and wild type (WT) mice were used for excitotoxic hippocampal injury. Thirty-two female adult PrP-hCAST and littermate controls of WT mice, weighing 20–25 g, were used for spinal contusion injury. Animals were kept under standard housing conditions in the Division of Laboratory Animal Resources sector of the University of Kentucky Medical Center, which is fully accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All experimental procedures were approved and performed in accordance with the Guidelines of the US National Institutes of Health and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Kentucky.

The mice were bred on a FVB/N background in our animal facilities. Mice were genotyped using primers phgPrP5' (5' GAAC TGAACCATTTCAACCGAG3') and phgPrP3' (5' AGAGCTACAGG TGGATAACC3').18 These PrP-hCAST Tg mice showed robust expression of human calpastatin, and no human calpastatin expression was noted in littermate controls (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Hippocampal calpastatin messenger ribonucleic acid mRNA expression in wild type (WT) and human calpastatin (hCAST) transgenic (Tg) mice. The hCAST Tg mice (±) positive for the hCAST gene (lane 3 and lane 4) were identified by pollymerase chain reaction with primers 5′-GAAC TGAACCATTTCAACCGAG-3′ and 5′-GCAGC TGTAGGC GACCCACAGG TGAAG-3′.

Organotypic hippocampal slice culture

Organotypic hippocampal slice cultures were prepared as described previously.19 Briefly, seven-day-old neonatal hCAST Tg or WT mouse pups were euthanized, and brains were removed immediately into ice cold culture medium. The culture medium was composed of MEM (Minimum Essential Medium containing Hanks salts and l-glutamine, Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD), 25 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO), 36 mM glucose (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 25% Hanks Balanced salt solution (Gibco), 25% heat inactivated horse serum (Sigma Aldrich Co.), and 50 mM penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco).

Bilateral hippocampi were dissected, cleaned of extra tissue under dissecting microscopy, and then sectioned coronally at 200 μm using McIlwain Tissue Chopper (Mickle Laboratory Engineering Co. Ltd., Gomshall, UK). Morphologically intact slices were placed into fresh culture medium (1 mL) in a six-well plate that contained pre-warmed porous Teflon membrane inserts (Millicell-CM 0.4 μm, Millipore, Marlborough, MA) at 37°C and 5% CO2/95% air. There were 3–5 slices plated onto each insert. To allow the slices exposure to the air, the slices were covered with only a film of medium, and extra medium from the top of the membrane insert was aspirated. The slices were cultured for four days to attach to the insert membrane before any experiments were performed. Slices were fed on day 4 with fresh culture medium.

Hippocampal slice cultures were prepared from seven-day-old mouse pups as described previously.19 Five days later, the cultures were treated with a different concentration of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) (5, 10, or 20 μM, Sigma) and propidium iodide (PI, Sigma, 2.5 μg/mL) for 24 h.

Neuronal death was assessed by measurement of PI uptake as described previously.19 Propidium iodide is a fluorescent molecule that binds to deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) by intercalating between the bases. It is excluded from healthy cells, but after membrane damage gains access to nuclear DNA in injured cells.20 The PI-labeled cell death signal at 24 h after NMDA insult was imaged and analyzed by SPOT Advanced software for Windows (W. Nushbaum Inc., Mc Henry, IL) using 5X objective on an inverted Leica DMIRB fluorescent microscopy image system (n = 5 slices per animal, n = 4–6 animals per group).

Fluorescent intensity of PI images was analyzed with Image J Software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda) for densitometry. For each animal, the calculated fluorescent intensity of PI image for cell death was averaged. Then, the average intensity per slice of all animals in each group was averaged to obtain a mean value per slice. Exposure conditions and times were identical for all images.

To determine the mechanism by which the hCAST expression protects neurons against NMDA-induced neuron death, injury, αII-spectrin breakdown (including the 145 kDa calpain specific breakdown product) was evaluated using Western blotting as described previously.51 At 24 h after NMDA insult, slices were treated with lysis buffer (62.5 mM Tris, M urea, 10% glycerol, and 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], pH 6.8) and prepared for assessment of spectrin degradation using Western blot analysis.

Contusive SCI

Contusion SCI was produced after a T9 laminectomy using an Infinite Horizons (IH) SCI device (Precision Systems & Instrumentation, Lexington, KY) as described previously.6,7 Briefly, adult female PrP-hCAST Tg or WT mice, weighing 20–25 g, were anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg, intraperitoneal [ip]) and xylazine (14 mg/kg, ip), and a laminectomy was performed to expose spinal segment T9. The exposed vertebral column was stabilized by clamping the rostral T8 and caudal T10 vertebral bodies with two spinal forceps. The SCI was then applied with the IH device using a 70 kdyn force setting, which resulted in severe contusion injury.

Impact analyses, including actual force applied to the spinal cord, displacement of spinal cord, and velocity, were recorded. The impact tip was automatically retracted immediately, the wound irrigated with saline, and the muscle and skin openings were closed with sutures. Sham animals received a laminectomy only. After the surgical procedure, all animals were placed on a heating pad set at 37°C until consciousness and mobility (upper limbs) was regained. Post-operative care included the manual expression of bladders twice daily until recovery of bladder function, injection with 3–5 mL sterile saline administered subcutaneously (sc) immediately after surgery, 33.3 mg/kg cefazolin, administered by intramuscular injection, twice a day for one week.

At 24 h post-injury, PrP-hCAST or WT mice were euthanatized by pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, ip injection) and decapitated. A 5-mm block of spinal cord centered on T9 was removed and snap-frozen on dry ice, then stored at -80°C. The spinal cord samples were homogenized in a lysis buffer and sonicated. The protein samples were obtained by microcentrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. Protein quantities in supernatant were determined using the bicinchoninic assay method.21–23

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously.21–23 Briefly, protein samples (30 μg of protein extract each sample with 2X laemmli sample buffer) were loaded on SDS-PAGE gels and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were probed with a polyclonal antibody against α-spectrin (1:1000, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) or calpastatin (1:1000, specific for human calpastatin, Santa Cruz Biotech, Dallas, TX) and reprobed with a monoclonal antibody against actin (1:1000, Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Blots were then incubated with infrared-labeled antirabbit or antimouse secondary antibodies (1:5000). All blots were visualized on the LI-COR Odyssey infrared imaging system and analyzed using LI-COR Image Studio (Lincoln, NE).

Assessment of locomotor function

Locomotor function was measured using the Basso Mouse Scale (BMS) as described previously.12,24 The BMS score is a 0 to 9 point scale, with subscore ranges from 0 to 11, which measures locomotor function after thoracic contusive SCI in mice; it is based on assessment of ankle extension, hindlimb joint movements, trunk stability, stepping coordination, paw placement, and tail position.24 Two investigators trained in BMS evaluation at Ohio State University performed the BMS testing. The two examiners were blinded to the genotype of each animal. The BMS testing was performed before injury, at three and seven days post-injury, then weekly until four weeks post-injury. The BMS scores or subscores were averaged for left and right hindlimbs to obtain a value per mouse.12,24

Assessment of tissue sparing

At four weeks post-injury, animals were euthanatized and transcardially perfused with ice-cold saline followed by phosphate-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Spinal cord blocks 2 cm in length, centered at the lesion epicenter, were dissected, post-fixed in the same 4% PFA solution overnight at 4°C followed by submersion in 25% sucrose solution at 4°C to ensure cryoprotection. The spinal cords were cryosectioned serially at a thickness of 20 μm. Each section was mounted onto gelatin-coated slides and stored at -20°C.

A modified eriochrome cyanine staining protocol for myelin that differentiates both white matter and cell bodies was used to visualize spared spinal tissue. Area measurements in lesion, gray matter, white matter, and total spinal tissue and calculation of lesion volume, total tissue sparing, white matter sparing, and gray matter sparing in transverse sections of the injured cords were performed as described previously.6,7,22,25

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using StatView (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), Group differences were evaluated by t test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), or repeated measures ANOVA, and Bonferroni post hoc test.26 Null hypotheses were rejected at the p < 0.05 level. Although the Basso Mouse Scale is an ordinal scale, differences between the treatments were compared using parametric statistical methods recommended by Scheff and colleagues.27

Results

Hippocampal slice cultures

The polymerase chain reaction analysis of DNA samples of hippocampus culture from PrP-hCAST ± and WT mice showed robust expression of human calpastatin in Prp-hCAST hippocampus, and no human calpastatin expression was noted in WT littermate controls (Fig. 1).

Calpastatin overexpression reduced α-spectrin degradation (145 kDa) 24 h after NMDA injury at all three NMDA concentrations, compared with WT control (Fig. 2, *p < 0.05 vs. WT-NMDA). These data suggest that calpastatin overexpression reduces calpain activity in hippocampal slice cultures 24 h after NMDA injury.

FIG. 2.

Calpastatin overexpression reduced calpain activity after N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) hippocampal injury. The α-Spectrin proteolysis after NMDA hippocampal injury was evaluated using Western blotting in wild type (WT) and prion promoter human calpastatin (PrP-hCAST) transgenic (Tg) organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. Both calpains and caspases cleave α-spectrin (240 kDa) to produce a 150 kDa fragment, while the 145 kDa breakdown product results exclusively from calpain proteolysis. Calpastatin overexpression reduced α-spectrin degradation (145 KDa) 24 h after NMDA injury at all three NMDA concentrations, compared with WT-control. Data are represented as the proteolytic fragment band normalized to intact spectrin (measured as optical density units) and expressed as mean +/− standard error of the mean and analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni analysis. *p < 0.05 vs. WT-NMDA Control, n = 5 slices per animal, n = 4–6 animals per group. Representative blots are shown in the top panel.

The NMDA administration (5–20 μM) caused a significant increase in PI staining in the hippocampal CA1 region, and calpastatin overexpression in PrP-hCAST mice significantly reduced the NMDA damage at 5 μM in both hippocampal regions compared with WT control (Fig. 3). At higher NMDA concentrations of 10 and 20 μM, the protection afforded by CAST overexpression did not reach statistical significance.

FIG. 3.

Calpastatin overexpression attenuated neuronal death after N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) hippocampal injury. (Bottom panel): Neuronal death was assessed by measurement of propidium iodide (PI) uptake after 24 h exposure to NMDA (5, 10, or 20 μM). The NMDA administration caused a significant increase in PI staining in the hippocampal CA1 region, and calpastatin overexpression in prion promoter human calpastatin (PrP-hCAST) mice significantly reduced the NMDA damage at 5 μM in both hippocampal regions compared with wild type (WT) control. At higher NMDA concentrations of 10 and 20 μM, the protection afforded by CAST overexpression did not reach statistical significance. (Top panel): Representative images of PI fluorescence after 24 h of NMDA exposure. Data were presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with repeated measures analyis of variance followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis. ##p < 0.01 vs. NMDA 5 μM-treated WT cultures; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. WT-control, n = 5 slices per animal, n = 4–6 animals per group.

In vivo studies, hCAST Tg mice

Western blot analysis of protein samples of spinal cord from PrP-hCAST ± or WT mice showed that the presence of the CAST transgene resulted in high expression of human calpastatin protein in the spinal cord of Tg mice (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Spinal calpastatin expression 24 h after spinal cord injury (SCI) in prion promoter human calpastatin (PrPhCAST) transgenic (Tg) mice. Western blot data using an antibody recognizing human calpastatin in the spinal cord of wild type (WT) and PrPhCAST Tg mice. The presence of the CAST transgene resulted in high expression of human calpastatin protein in spinal cord of Tg mice 24 h after SCI. Immunoblot for human calpastatin in spinal cord homogenates of Pr hCAST Tg mice at 24 h after SCI.

After contusive injury to the thoracic spinal cord, calpain activity was assessed by quantifiying αII-spectrin breakdown, particularly the 145 kDa breakdown product. In PrP-hCAST mice, calpastatin overexpression reduced α-spectrin degradation compared with WT control (Fig. 5). These data suggest that calpastatin overexpression reduces calpain activity in the spinal cord 24 h after contusive SCI in mice. This time point was chosen as a time of maximal calpain activation, as detected by spectrin breakdown.1

FIG. 5.

Calpastatin overexpression reduced calpain-mediated degradation of α-spectrin after contusive spinal cord injury (SCI) in human calpastatin (hCAST) transgenic (Tg) mice. After contusive injury to the thoracic spinal cord, calpain activity was assessed by quantifiying αII-spectrin breakdown, particularly the 145 kDa breakdown product using Western blot. In prion promoter human calpastatin (PrP-hCAST) mice, calpastatin overexpression (n = 2) reduced α-spectrin degradation 24 h after SCI compared with WT-control (n = 3). Data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean and analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis. *p < 0.05, vs. WT-control. Representative blots spectrin breakdown in spinal cord homogenates of wild type (WT) and PrP hCAST Tg mice at 24 h after SCI are shown at top panel.

Twenty-two hCAST Tg and WT mice received contusive injury using the IH impactor at the 70 kdyn force setting. Immediately after SCI, all animals exhibited complete bilateral hindlimb paralysis. Calpastatin overexpressing mice displayed a significant improvement in locomotor function at one and three weeks after contusive SCI compared with the WT controls (Fig. 6). Differences in BMS subscores did not reach statistical significance. `

FIG. 6.

Calpastatin overexpression improved locomotor function after spinal cord injury (SCI). Calpastatin overexpressing mice (n = 13) increased Basso Mouse Scale (BMS) scores at one and three weeks after contusive SCI compared with the wild type (WT) controls (n = 9). Differences in BMS subscores did not reach statistical significance. Contusive SCI was produced using the Infinite Horizons impactor, 70 kdyn setting, at T9. Data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean and analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis, *p < 0.05 vs. WT-control. hCAST-Tg, human calpastatin transgenic.

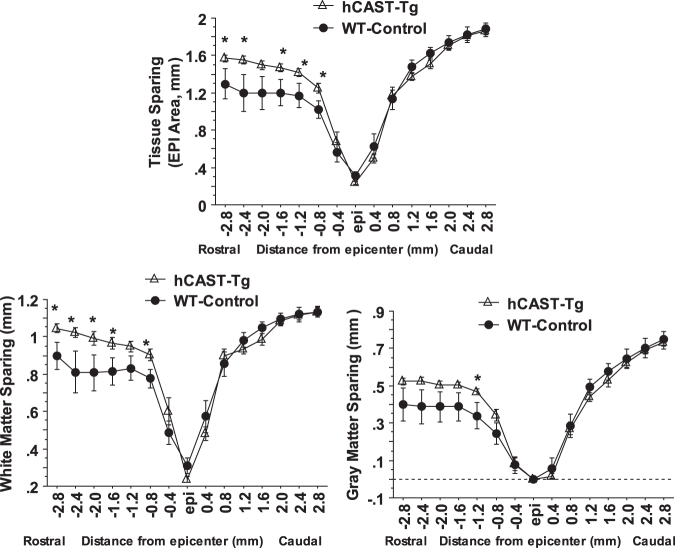

Histological assessment of lesion volume and tissue sparing showed that calpastatin overexpression resulted in a significant decrease in lesion volume (Fig. 7D) and significant increase in tissue sparing rostral to the lesion epicenter, including both white matter and gray matter sparing (Fig. 8 and 9), at four weeks post-injury compared with WT animals.

FIG. 7.

(A,B,C): Injury parameters. No significant differences in impact force, displacement, and velocity were found between the human calpastatin (hCAST) transgenic (CAST-Tg, n = 13) and wild type (WT) mice (WT-Control, n = 9), indicating similar injuries to all animals. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean. (D) Calpastatin overexpression decreased lesion volume and increased tissue sparing after contusive spina cord injury in hCAST Tg mice. Calpastatin overexpression in Tg mice resulted in a significant decrease in lesion volume after contusion injury to the spinal cord. Injury conditions and treatment groups are as described in Figure 6. Data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean and analyzed with t test, *p < 0.05 vs. WT-control.

FIG. 8.

Calpastatin overexpression increased tissue sparing after contusive SCI in human calpastatin (hCAST) transgenic mice. Calpastatin overexpression in transgenic mice resulted in a significant increase in tissue sparing, white matter sparing, and gray matter sparing rostral to the lesion epicenter at four weeks post-injury compared with wild type (WT) animals. Injury conditions and treatment groups are as described in Figure 6. Data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean and analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis, *p < 0.05 vs. WT-control.

FIG. 9.

Photomicrographs of representative transverse spinal cord sections from prion promoter human calpastatin (Prp-hCAST) transgenic mouse and WT mouse at 28 days after contusive spinal cord injury (SCI, 70 kdyn). The sections were from the lesion epicenter and rostral/caudal to the lesion epicenter, obtained from a Prp-hCAST transgenic mouse (top panel) and WT mouse (bottom panel) after contusive SCI. The sections were stained with eriochrome cyanine for myelin. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Discussion

Excessive calpain activation is strongly implicated in neurodegeneration after excitotoxic injury and SCI.1,28–30 Although small molecule calpain inhibitors protect against the neurodegeneration,2,5,6,31–33 most calpain inhibitors are non-specific and also inhibit cysteine cathepsins such as cathepsin B and other proteases.11,34,35 The only specific inhibitor of classical calpains is calpastatin.16,17,36

In the present study, we used PrP-hCAST Tg mice that overexpress calpastatin in neurons18 to evaluate the ability of calpastatin overexpression to inhibit calpain activity, protect against NMDA-mediated excitotoxicity in hippocampal slice cultures, and attenuate the pathology and functional deficits resulting from an in vivo model of traumatic SCI in mice. Our results demonstrate calpastatin overexpression results in calpain inhibition, assessed by quantifying the 145 kDa aII spectrin breakdown product after both NMDA exposure to hippocampal slice cultures and SCI.

Calpastatin overexpression also protected against NMDA-induced neuron death, particularly at lower NMDA concentrations, and improved pathological and functional outcomes after contusive injury to the thoracic spinal cord. Although calpains have both pathological and physiological functions, these results support the hypothesis that sustained activation of calpain-dependent proteolysis contributes to neurodegeneration after excitotoxic injury and traumatic SCI.

Excitotoxic hippocampal injury

Traumatic injury to the brain and spinal cord causes a primary injury at the time of trauma and a secondary damage cascade that results in further neuronal loss and neurological dysfunction.2,37,38 Glutamatergic excitotoxicity associated with increased cytosolic Ca2+ levels and calpain activation plays key roles in the development of secondary damage after excitotoxic hippocampal injury and traumatic SCI.13,19,37–39

To determine whether calpastatin overexpression attenuates calpain activity and excitotoxic injury, the organotypic hippocampal slice culture (OHSC) was chosen as an in vitro model. The OHSCs provide an intact neuronal cytoarchitecture with a high concentration of NMDA-receptors that is particularly suitable for the testing of the mechanisms of the excitotoxic injury and neuroprotection.19,40 The vulnerability of the CA1 region to NMDA is consistent with previous studies and with the high density of NMDA receptors in this region in vivo.41–43

Neuroprotection afforded by CAST overexpression was restricted to lower doses of NMDA. The decreased neuroprotection at higher NMDA doses may reflect the involvement of additional signaling pathways in NMDA toxicity including oxidative/nitrosididative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and stress-activated protein kinases.44,45 In addition, calpastatin inhibits classical calpains such as calpains 1 and 2 that contain a EF hand domain, does not inhibit non-classical calpains that contain the protease core domain, but lack a penta-EF hand domain.11 Calpastatin binds to the penta-EF hand domains in the large and small subunits of classical calpains, as well as to the substrate-binding region.16,17,36,46 Several non-classical calpains are present in the CNS, including calpains 5, 7, and 10.12

Inhibition of calpain-mediated αII-spectrin degradation

Analysis of the breakdown products of aII spectrin can distinguish between calpain and caspase proteolysis 47 Both proteases can produce breakdown products of 150 kDa, while calpain also produces a 145 kDa breakdown product. The CAST overexpression attenuated the appearance of the 145 kDa aII spectrin breakdown product after treatment of hippocampal slice cultures with each of the NMDA concentrations, demonstrating that the reduced neuroprotection observed at the higher NMDA doses was not the result of less effective calpain inhibition. Similarly, the reduced expression of 145 kDa spectrin breakdown products in the spinal cord of PrP-hCAST Tg mice compared with WT controls demonstrates effective calpain inhibition resulting from CAST overexpression in the spinal cord.

Attenuation of post-traumatic locomotor dysfunction

More severe locomotor dysfunction developed in WT mice than in hCAST-Tg mice after contusive SCI. Overexpression of calpastatin reduced calpain-specific breakdown products of αII-spectrin and also improved tissue sparing rostral to the lesion. The reason the tissue sparing achieved with calpastatin overexpression was primarily rostral to the injury epicenter is uncertain, however. One possibility is more extensive calpain activation rostral to the injury, although this was not evaluated in the present study.48 In a previous study, tissue sparing after instraspinal administration of MDL28170 was also predominantly rostral to the lesion.7 Modest tissue sparing caudal to the lesion was observed in another study, however,6 and calpain 1 knockdown resulted in tissue sparing both rostral and caudal to the injury epicenter.49

The improved functional and pathological outcomes with CAST overexpression are consistent with those obtained with treatment of small molecular calpain inhibitor and calpain 1 knockdown by lentiviral calpain 1 shRNA after SCI in our previous studies9,21 and support the involvement of calpain activation in mechanisms underlying locomotor disability after traumatic SCI. The compounds used in our previous studies have poor pharmacological characteristics and make the exact contribution of the calpains uncertain because they also inhibit other classes of proteases.

Limitation of calpastatin overexpression

While calpain overactivation is associated with pathology,2,37 calpains also serve essential physiological roles in cell signaling, cell migration, neuronal plasticity, and wound repair.13,38,50 The challenge is to inhibit the calpain overactivation contributing to pathology, but spare the essential physiological roles of various calpain isoforms.

The CAST overexpression inhibits calpains 1 and 2, but not non-classical/non-conventional calpains present in the CNS.15–17 The improved pathological and functional outcomes resulting from CAST overexpression therefore suggest that the non-classical calpains may play relatively minor roles in neurodegeneration associated with excitotoxic insult and SCI.

Recent data further suggest that calpains 1 and 2 play contrasting roles in neuroprotection and neurodegeneration. Calpain 1 activation is implicated in beneficial roles of calpain activation including synaptic plasticity and neuroprotection, while calpain-2 activation is neurodegenerative.14,51 Increased calpain 2 immunoreactivity is observed after SCI.29 Previous studies had suggested, however, that calpain 1 activation is specifically linked to excitotoxic injury,39 and calpain 1 knockdown was found to protect against SCI.49 Based on mRNA levels, calpain 2 is expressed at much higher levels than calpain 1 in the rat CNS, with similar results observed in mouse brain.12 The specific contribution of calpain 2 to neurodegeneration after SCI remains to be investigated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the KSCHIRT Grant (7-6A to C.G.Y./J.W.G) and NIH Grant P01 NS05484 (J.W.G). We thank Kashif Raza, Lauren Thompson, and Brantley Graham, DVM, for assistance with assessment of locomotor function/tissue sparing and care of the mouse colony.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Springer J.E., Azbill R.D., Kennedy S.E., George J., and Geddes J.W. (1997). Rapid calpain I activation and cytoskeletal protein degradation following traumatic spinal cord injury: attenuation with riluzole pretreatment. J. Neurochem. 69, 1592–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ray S.K., Hogan E.L,. and Banik N.L. (2003). Calpain in the pathophysiology of spinal cord injury: neuroprotection with calpain inhibitors. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 42, 169–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dumont R.J., Okonkwo D.O., Verma S., Hurlbert R.J., Boulos P.T., Ellegala D.B., and Dumont A.S. (2001). Acute spinal cord injury, part I: pathophysiologic mechanisms. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 24, 254–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siddiqui A.M., Khazaei M., and Fehlings M.G. (2015). Translating mechanisms of neuroprotection, regeneration, and repair to treatment of spinal cord injury. Prog. Brain Res. 218, 15–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schumacher P.A., Siman R.G., and Fehlings M.G. (2000). Pretreatment with calpain inhibitor CEP-4143 inhibits calpain I activation and cytoskeletal degradation, improves neurological function, and enhances axonal survival after traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Neurochem. 74, 1646–1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yu C.G., and Geddes J.W. (2007). Sustained calpain inhibition improves locomotor function and tissue sparing following contusive spinal cord injury. Neurochem. Res. 32, 2046–2053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yu C.G., Joshi A., and Geddes J.W. (2008). Intraspinal MDL28170 microinjection improves functional and pathological outcome following spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 25, 833–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Colak A., Kaya M., Karaoglan A., Sagmanligil A., Akdemir O., Sahan E., and Celik O. (2009). Calpain inhibitor AK 295 inhibits calpain-induced apoptosis and improves neurologic function after traumatic spinal cord injury in rats. Neurocirugia (Astur) 20, 245–254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang S.X., Bondada V., and Geddes J.W. (2003). Evaluation of conditions for calpain inhibition in the rat spinal cord: effective postinjury inhibition with intraspinal MDL28170 microinjection. J. Neurotrauma 20, 59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Siklos M., BenAissa M., and Thatcher G.R. (2015). Cysteine proteases as therapeutic targets: does selectivity matter? A systematic review of calpain and cathepsin inhibitors. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 5, 506–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ono Y., Saido T.C., and Sorimachi H. (2016). Calpain research for drug discovery: challenges and potential. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 854–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Singh R., Brewer M.K., Mashburn C.B., Lou D., Bondada V., Graham B., and Geddes J.W. (2014). Calpain 5 is highly expressed in the central nervous system (CNS), carries dual nuclear localization signals, and is associated with nuclear promyelocytic leukemia protein bodies. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 19383–19394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu J., Liu M.C., and Wang K.K. (2008). Calpain in the CNS: from synaptic function to neurotoxicity. Sci. Signal. 1, re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baudry M., and Bi X. (2016). Calpain-1 and calpain-2: The yin and yang of synaptic plasticity and neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci. 39, 235–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goll D.E., Thompson V.F., Li H., Wei W., and Cong J. (2003). The calpain system. Physiol. Rev. 83, 731–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wendt A., Thompson V.F., and Goll D.E. (2004). Interaction of calpastatin with calpain: a review. Biol. Chem. 385, 465–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hanna R.A., Campbell R.L., and Davies P.L. (2008). Calcium-bound structure of calpain and its mechanism of inhibition by calpastatin. Nature 456, 409–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schoch K.M., von Reyn C.R., Bian J., Telling G.C., Meaney D.F., and Saatman K.E. (2013). Brain injury-induced proteolysis is reduced in a novel calpastatin-overexpressing transgenic mouse. J. Neurochem. 125, 909–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Butler T.R., Self R.L., Smith K.J., Sharrett-Field L.J., Berry J.N., Littleton J.M., Pauly J.R., Mulholland P.J., and Prendergast M.A. (2010). Selective vulnerability of hippocampal cornu ammonis 1 pyramidal cells to excitotoxic insult is associated with the expression of polyamine-sensitive N-methyl-D-asparate-type glutamate receptors. Neuroscience 165, 525–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cummings B.S., and Schnellmann R.G. (2004). Measurement of cell death in mammalian cells. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. Chapter 12, Unit. 12.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Amini M., Ma C.L., Farazifard R., Zhu G., Zhang Y., Vanderluit J., Zoltewicz J.S., Hage F., Savitt J.M., Lagace D.C., Slack R.S., Beique J.C., Baudry M., Greer P.A., Bergeron R., and Park D.S. (2013). Conditional disruption of calpain in the CNS alters dendrite morphology, impairs LTP, and promotes neuronal survival following injury. J. Neurosci. 33, 5773–5784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yu C.G., Yezierski R.P., Joshi A., Raza K., Li Y., and Geddes J.W. (2010). Involvement of ERK2 in traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Neurochem. 113, 131–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yu C.G., and Yezierski R.P. (2005). Activation of the ERK1/2 signaling cascade by excitotoxic spinal cord injury. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 138, 244–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Basso D.M., Fisher L.C., Anderson A.J., Jakeman L.B., McTigue D.M., and Popovich P.G. (2006). Basso Mouse Scale for locomotion detects differences in recovery after spinal cord injury in five common mouse strains. J. Neurotrauma 23, 635–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rabchevsky A.G., Fugaccia I., Sullivan P.G., Blades D.A., and Scheff S.W. (2002). Efficacy of methylprednisolone therapy for the injured rat spinal cord. J. Neurosci. Res. 68, 7–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McTigue D.M., Tripathi R., Wei P., and Lash A.T. (2007). The PPAR gamma agonist Pioglitazone improves anatomical and locomotor recovery after rodent spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 205, 396–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Scheff S.W., Saucier D.A., and Cain M.E. (2002). A statistical method for analyzing rating scale data: the BBB locomotor score. J. Neurotrauma 19, 1251–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. del Cerro S., Arai A., Kessler M., Bahr B.A., Vanderklish P., Rivera S.. and Lynch G. (1994). Stimulation of NMDA receptors activates calpain in cultured hippocampal slices. Neurosci. Lett. 167, 149–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li Z., Hogan E.L., and Banik N.L. (1995). Role of calpain in spinal cord injury: increased mcalpain immunoreactivity in spinal cord after compression injury in the rat. Neurochem. Int. 27, 425–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berry J.N., Sharrett-Field L.J., Butler T.R., and Prendergast M.A. (2012). Temporal dependence of cysteine protease activation following excitotoxic hippocampal injury. Neuroscience 222, 147–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nimmrich V., Reymann K.G., Strassburger M., Schoder U.H., Gross G., Hahn A., Schoemaker H., Wicke K., and Moller A. (2010). Inhibition of calpain prevents NMDA-induced cell death and beta-amyloid-induced synaptic dysfunction in hippocampal slice cultures. Br. J. Pharmacol. 159, 1523–1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lopez-Picon F.R., Kukko-Lukjanov T.K., and Holopainen I.E. (2006). The calpain inhibitor MDL-28170 and the AMPA/KA receptor antagonist CNQX inhibit neurofilament degradation and enhance neuronal survival in kainic acid-treated hippocampal slice cultures. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 2686–2694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang Z., Huang Z., Dai H., Wei L., Sun S., and Gao F. (2015). Therapeutic efficacy of E-64-d, a selective calpain inhibitor, in experimental acute spinal cord injury. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 134242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang K.K. (1990). Developing selective inhibitors of calpain. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 11, 139–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mehdi S. (1991). Cell-penetrating inhibitors of calpain. Trends Biochem. Sci. 16, 150–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moldoveanu T., Gehring K., and Green D.R. (2008). Concerted multi-pronged attack by calpastatin to occlude the catalytic cleft of heterodimeric calpains. Nature 456, 404–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saatman K.E., Creed J., and Raghupathi R. (2010). Calpain as a therapeutic target in traumatic brain injury. Neurotherapeutics 7, 31–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Doshi S., and Lynch D.R. (2009). Calpain and the glutamatergic synapse. Front. Biosci. (Schol. Ed.) 1, 466–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Siman R., Noszek J.C., and Kegerise C. (1989). Calpain I activation is specifically related to excitatory amino acid induction of hippocampal damage. J. Neurosci. 9, 1579–1590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ebrahimi F., Hezel M., Koch M., Ghadban C., Korf H.W., and Dehghani F. (2010). Analyses of neuronal damage in excitotoxically lesioned organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. Ann. Anat. 192, 199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kristensen B.W., Noraberg J., and Zimmer J. (2001). Comparison of excitotoxic profiles of ATPA, AMPA, KA and NMDA in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. Brain Res. 917, 21–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vornov J.J., Tasker R.C., and Coyle J.T. (1991). Direct observation of the agonist-specific regional vulnerability to glutamate, NMDA, and kainate neurotoxicity in organotypic hippocampal cultures. Exp. Neurol. 114, 11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Monaghan D.T., and Cotman C.W. (1985). Distribution of N-methyl-D-aspartate-sensitive L-[3H]glutamate-binding sites in rat brain. J. Neurosci. 5, 2909–2919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Forder J.P., and Tymianski M. (2009). Postsynaptic mechanisms of excitotoxicity: involvement of postsynaptic density proteins, radicals, and oxidant molecules. Neuroscience 158, 293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hardingham G.E. (2009). Coupling of the NMDA receptor to neuroprotective and neurodestructive events. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 1147–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kiss R., Kovacs D., Tompa P., and Perczel A. (2008). Local structural preferences of calpastatin, the intrinsically unstructured protein inhibitor of calpain. Biochemistry 47, 6936–6945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang Z., Larner S.F., Liu M.C., Zheng W., Hayes R.L., and Wang K.K. (2009). Multiple alphaII-spectrin breakdown products distinguish calpain and caspase dominated necrotic and apoptotic cell death pathways. Apoptosis 14, 1289–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sribnick E.A., Matzelle D.D., Banik N.L., and Ray S.K. (2007). Direct evidence for calpain involvement in apoptotic death of neurons in spinal cord injury in rats and neuroprotection with calpain inhibitor. Neurochem. Res. 32, 2210–2216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yu C.G., Li Y., Raza K., Yu X.X., Ghoshal S., and Geddes J.W. (2013). Calpain 1 knockdown improves tissue sparing and functional outcomes after spinal cord injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma 30, 427–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kuchay S.M., and Chishti A.H. (2007). Calpain-mediated regulation of platelet signaling pathways. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 14, 249–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Baudry M. (2019). Calpain-1 and calpain-2 in the brain: Dr. Jekill and Mr. Hyde? Curr. Neuropharmacol. 17, 823–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]