Abstract

Conventional long-term ventricular assist devices continue to be extremely problematic due to infections caused by percutaneous drivelines and thrombotic events associated with the use of blood-contacting surfaces. Here we describe a muscle-powered cardiac assist device that avoids both these problems by using an internal muscle energy converter to drive a non-blood-contacting extra-aortic balloon pump. The technology was developed previously in this lab and operates by converting the contractile energy of the latissimus dorsi muscle into hydraulic power that can be used, in principle, to drive any blood pump amenable to pulsatile actuation. The two main advantages of this implantable power source are that it 1) significantly reduces infection risk by avoiding a constant skin wound, and 2) improves patient quality-of-life by eliminating all external hardware components. The counterpulsatile balloon pumps, which compress the external surface of the ascending aorta during the diastolic phase of the cardiac cycle, offer another critical advantage in the setting of long-term circulatory support in that they increase cardiac output and improve coronary perfusion without touching the blood. The goal of this work is to combine these two technologies into a single circulatory support system that eliminates driveline complications and avoids surface- mediated thromboembolic events, thereby providing a safe, tether-free means to support the failing heart over extended - or even indefinite - periods of time.

Index Terms: EABP, extra-aortic balloon pump, cardiac assist device, cardiac support, counterpulsation, destination therapy, muscle-powered, VAD, ventricular assist device

I. Introduction

A. Congestive Heart Failure

CONGESTIVE heart failure (CHF), a progressive condition in which cardiac function deteriorates over time, remains one of the most costly diseases in the industrialized world, both in terms of healthcare dollars and the loss of human life. It is the number one cause of death worldwide. In the United States alone, where roughly 5 million are currently living with CHF, the economic impact is estimated to exceed $40 billion per year in medical costs and lost productivity [1], [2]. Worse still, roughly half of all people who develop CHF die within five years of diagnosis due to the limitations of current long-term treatment strategies [2], [3].

Cardiac transplantation is considered to be the best recourse for end-stage CHF patients, but this treatment option is not available to most patients due to a limited donor pool. Pharmacologic therapies can relieve the symptoms and improve heart function in the short term but are unable to restore and maintain normal heart function over the long term. Therefore, ventricular assist devices (VADs) became a major treatment option over the years. Despite decades of developmental work however, the majority of VADs are still used in a limited capacity—usually as a stopgap measure to ‘bridge’ patients to transplantation—due to two persistent limitations: bacterial infection of percutaneous drivelines and thromboembolic complications associated with blood-contacting surfaces [4]–[6]. The development of a completely self-contained, non-blood-contacting cardiac assist device for long-term use could therefore be a significant advance in circulatory support technology.

B. Harnessing Skeletal Muscle as an Internal Power Source

Given the persistent difficulties encountered with existing blood pump technologies used in the chronic setting, the promise of safe, reliable long-term circulatory support is likely to remain unfulfilled unless and until there is a fundamental change in the way we approach this problem. The research by our group suggests an entirely new means to deal with longstanding problems created by drivelines and blood contacting surfaces. Our approach is to avoid them altogether by harnessing the body’s own endogenous energy stores (i.e., skeletal muscle) and applying this power to the external surface of the heart or ascending aorta [7]–[9].

The primary enabling technology behind this work is an implantable muscle energy converter (MEC, Fig. 1A) developed by the senior author (DRT) under the auspices of the Whitaker Foundation and the National Institutes of Health [10]. The MEC is an internal energy transfer mechanism that utilizes electrically stimulated latissimus dorsi muscle (LDM) as an endogenous power source and transmits this energy in hydraulic form. Through numerous iterative design improvements implemented over several years, this device has been refined and shown to exhibit excellent anatomic fit, extreme mechanical durability and high energy transfer efficiency (>90%) with the capacity to transmit more than 1.25 J of energy per actuation cycle [7], [10]–[12]. This compares favorably to the work generated by healthy left ventricles, which, when pumping 5.0 L/min against a mean pressure of 100 mmHg at 72 beats per minute, deliver 0.925 joules/stroke to the bloodstream. From an energetic perspective, this means that the MEC could, in principle, provide 100% systemic circulatory support if a target VAD could be made to deliver maximum sustainable MEC power to the bloodstream with an efficiency of 74% with every heartbeat.

Fig. 1.

Computer rendering of the MEC device shown in full (A) and ¾ cross sectional (B) views. 1) Actuator Arm, 2) Rotary Cam, 3) Spring Bellows, 4) Piston, and 5) Outlet Port.

The LDM is especially well-suited for use as the MEC’s power source due to its large size, surgical accessibility, proximity to the thoracic cavity, and steady state work capacity sufficient for long-term cardiac support [13]. Secure muscle-device fixation is achieved using an artificial tendon sewn into the humeral insertion of the LDM, which is then anchored to the actuator arm (Fig. 1B–1) of the MEC using a patented clamp-and-loop technique [10]. LDM contractions are controlled by a programmable pacemaker-like device (cardiomyostimulator) that coordinates muscle activity with the cardiac cycle. As the actuator arm (Fig. 1B–1) rotates upward in response to LDM shortening, a rotary cam (Fig. 1B–2) compresses a metallic spring bellows (Fig. 1B–3) and a piston (Fig. 1B–4) located directly underneath, ejecting 5 mL of pressurized fluid through the outlet port (Fig. 1B–5).

The potential advantages of this approach to long-term circulatory support are significant. By efficiently translating stimulated contractile energy into hydraulic power, the MEC serves to both reduce the risk of infection across the skin and enhance patient quality-of-life by eliminating the need for external hardware components such as extracorporeal battery packs, transmission coils, and percutaneous drivelines. Moreover, muscle-powered VADs would, in principle, be far simpler to maintain and hence much less expensive in aggregate than traditional blood pumps used for destination therapy, thereby resulting in wider availability and reduced costs for healthcare providers [7], [10]–[12].

C. Extra Aortic Counterpulsation

This novel method of converting contractile energy into hydraulic power attains its value when this energy is successfully delivered to the bloodstream. Since Kantrowitz et al. first introduced extra-aortic counterpulsation in the early 1950’s, the diastolic counterpulsation technique has been a commonly used cardio-therapeutic mechanism that assists left ventricular function and augments coronary blood flow by lowering pressure afterloads in the aorta while increasing coronary perfusion [10]–[12], [14]–[16]. More recently, this support mechanism has been typically accomplished with inflatable balloon pumps that displace blood from within the aorta during the filling phase of the cardiac cycle. However, unlike current intra-aortic balloon pumps (IABPs) (Fig. 2A) that displace blood from the inside of the vessel, extra-aortic balloon pumps (EABP) (Fig. 2B) squeeze the aorta from the outside. Although this method still retains the risk of atheroembolism from atherosclerotic plaques due to the repeated compression of the ascending aorta, it largely precludes secondary complications associated with thromboembolism by avoiding contact with the bloodstream [17]–[21]. In this context, the C-Pulse EABP (Sunshine Heart Inc., Eden Prairie, MN) is an attractive target for muscle-powered cardiac assist due to its low power requirements and positive results in early clinical trials [17], [22]. Results from a study performed in eight CHF patients over a 6-month period show that the C-Pulse balloon inflation (20 mL) at the aortic root can effectively counterpulsate the heart and improve patient outcomes [23]. Unfortunately, direct application of the MEC for C-Pulse actuation is not possible since the MEC was designed for high-pressure, low-volume (5 mL) energy transmission. Thus, to combine these two technologies into a single circulatory support system, an intermediate device is needed to increase effective MEC displacement volume to match the target inflation volume of the C-Pulse device. Toward that end, an implantable volume amplification mechanism (iVAM) was designed to boost MEC output volumes by a factor of four. This tether-free, non-blood-contacting MEC-iVAM/EABP coupling will provide partial, but meaningful, circulatory support.

Fig. 2.

Unlike conventional intra-aortic copulsation balloon pump (A), extra-aortic counterpulsation balloon pump (B) wraps around the external surface of the ascending aorta and inflates and deflates in synchrony with ventricular diastole and systole (C), respectively, without touching the blood [22], [23], [40].

II. iVAM Design Elements

The following design elements and their attendant performance criteria were used to guide the course of iVAM development: A) volume amplification, B) anatomic fit, C) energy transfer efficiency, D) muscle force and speed requirements, E) work storage and delivery, F) material selection, and G) device durability. These seven key aspects of iVAM design are described below.

A. Volume Amplification

Volume amplification was accomplished using the area difference between two nested cylindrical spring bellows: an inner bellows that contains a partial vacuum within its area Ai and an outer bellows with an area Ao (Fig. 3). The 5 mL of pressurized fluid ejected from the MEC directly enters the iVAM, fills the annulus passage area (Aa) and extends the two bellows in unison. The input volume is amplified as the bellows pushes down piston B, ejecting the output fluid towards the EABP. Fine tuning of these internal component dimensions was required to create a durable) and implantable (i.e., compact for comfortable fit) device that amplifies the 5 mL MEC output to meet the 20 mL EABP inflation requirement.

Fig. 3.

Free body diagram of the MEC-iVAM complex showing the force distribution profile created during the ejection phase of device actuation.

B. Anatomic Fit

The MEC-iVAM complex (Fig. 4) was designed to sit across the ribcage with the upper portion of the MEC housing and sewing ring resting above the ribs, the lower portion of the MEC passing through the ribs, and the iVAM positioned below (i.e., completely within the chest cavity). Optimum anatomic fit was accomplished by minimizing the device dimensions (10.3 cm × 12.9 cm x 6.2 cm) and stacking the two devices one against the other so that the iVAM portion of the combined device is able to sit comfortably against in inner lining of the chest wall with minimal lung displacement. This arrangement not only provides a low-profile transthoracic fit but also reduces device weight and minimizes energy loss by shortening the fluid travel distance as explained in the following section.

Fig. 4.

The full (A) and ¾ cross-sectional (B) views of the linearly stacked MEC-iVAM complex that ensures a comfortable fit above the ribcage as well as within the thoracic cavity.

C. Energy Transfer Efficiency

The MEC-iVAM complex was designed to minimize turbulence and pressure gradients (ΔP) throughout the fluid flow path. To accomplish this, parametric computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations were run for five different MEC- iVAM interface opening designs (Table IA) and ten different iVAM outlet port designs (Table IB) using ANSYS Workbench (Canonsburg, PA). After the simulations were evaluated for low pressure gradients, low turbulence kinetic energy (TKE) and high laminarity of the flow path, we chose a combination of the Interface Opening Design #5 (Table IA) and Outlet Port Design #10 (Table IB), which features an enlarged flow path via eight interface openings positioned 30 degrees apart for low hydraulic resistance, a centered outlet port for minimal flow turbulence, and a linearly stacked configuration for short fluid travel distance.

TABLE I.

The Pressure Gradients (ΔP), Turbulence Kinetic Energies (TKE), and Flow Path Profiles of Five Different MEC-iVAM Interface Opening Designs (Shown in 1/4 Cross-Sectional Views) (A) and Ten Different iVAM Outlet Port Designs (Shown in 1/2 Cross-Sectional Views) (B)

| Design Iterations | ΔP [psi] | Max TKE [ft2/s2] | TKE Profile | Flow Path/Velocity Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A) MEC-iVAM Interface Opening Designs | ||||

| 1 | 0.0401 | 1.140 |  |

|

| 2 | 0.0104 | 1.579 |  |

|

| 3 | 0.0197 | 1.356 |  |

|

| 4 | 0.0119 | 0.503 |  |

|

| 5 | 0.0238 | 0.473 |  |

|

| B) iVAM Outlet Port Designs | ||||

| 1 | 0.031 | 3.846 |  |

|

| 2 | 0.041 | 1.967 |  |

|

| 3 | 0.210 | 4.451 |  |

|

| 4 | 0.209 | 4.924 |  |

|

| 5 | 0.210 | 5.148 |  |

|

| 6 | 0.660 | 3.938 |  |

|

| 7 | 0.531 | 5.221 |  |

|

| 8 | 0.552 | 2.342 |  |

|

| 9 | 0.121 | 2.152 |  |

|

| 10 | 0.162 | 2.006 |  |

|

To investigate the complete flow profile of the selected design combination, one-eighth of the MEC-iVAM complex 3D model was reconstructed for expedited flow analyses within the selected reduced volume. Boundary pressure and inlet and outlet flow rates were set to 1 atm and 19.9 mL/s, respectively, for water (ρH2O = 0.98 g/mL) operating at body temperature. Results show a laminar flow throughout the fluid path with the streamline velocity, density and trajectory (Fig. 5A) and an even pressure drop profile (Fig. 5B). The pressure drop across the entire fluid path was 0.0238 psi (1.23 hich was small enough to be neglected with respect to overall energy loss calculations (<0.2%).

Fig. 5.

CFD of a one-eighth section of the MEC-iVAM complex design that exhibits the most laminar flow (A) and even distribution of pressure gradient (B).

D. Muscle Force and Speed Requirements

The device is designed to operate at contractile force and velocity levels compatible with the functional capacity of fully conditioned human LDM, which at peak sustainable power production generates roughly 95 N force and shortens at a rate of 11 cm/s [24]. To confirm the muscle’s ability to reliably power this device, actuation force requirements of the MEC-iVAM complex were calculated.

Device actuation begins with lifting the MEC actuator arm, which was designed with a 5N preload force to allow the actuator arm to overcome the passive resting tension of a fully-trained LDM [10], [11]. Rapid rotation of the actuator arm (≤350 ms) is essential in order to complete inflation of the EABP during the first half of the diastolic period, but rapid return of the actuator arm to the home position is equally important since balloon deflation must be complete before the onset of cardiac systole (Fig. 2C) [25], [26]. Hence, the distribution of actuator arm forces in both forward- and return-stroke directions is a critical design consideration. These forces were adjusted via manipulation of two dynamic components internal to the MEC-iVAM complex: 1) metal bellows spring constants and directions and 2) partial vacuum pressures.

Material, thickness, inner and outer diameter, number of diaphragms, and the contour of the convolutions determine the spring constant of the bellows. The iVAM bellows material and thickness were set to stainless steel and 0.0762 mm (0.003 in) for a high spring constant for appropriate force contribution. The number of bellows convolutions, stroke length, and inner and outer diameters were set to fourteen, 0.411 cm (0.162 in), 7.092 cm (2.792 in), and 8.189 cm (3.224 in), respectively, to create an acceptable bellows life span (i.e., 194,040,000 cycles). Both MEC and iVAM bellows were installed at partially compressed states and tuned to produce both preload return-stroke force (KMEC • ΔSMEC) and an opposing force in the forward-stroke direction (KiVAM·• ΔSiVAM). The partial vacuum spaces created within the MEC housing (PMEC Vac ·• Am) and iVAM inner bellows (PMEC Vac ·• Ai) add force in the return-stroke direction, which helps to store energy within the device during LDM contraction (FLDM) for a rapid EABP deflation and reset of the actuator arm between contractions. These force vectors were compiled into a free body diagram (Fig. 3) and a force balance equation (1), which were used to determine that maximum actuation force.

| (1) |

Equation (1) is a force balance equation of the MEC-iVAM complex at equilibrium; Fcam: cam force; KMEC : spring constant of the MEC bellows; SMEC : stroke length of the MEC bellows; PMEC_Vac: pressure within the MEC vacuum space; Am: cross-sectional area of the MEC bellows; KiVAM: spring constant of the iVAM bellows; SiVAM: stroke length of the iVAM bellows; PiVAM_Vac: pressure within the iVAM vacuum space; Ai: cross-sectional area of the inner iVAM bellows; PMEC: hydraulic pressure of the 5mL fluid; Aa: annulus area between the inner and outer iVAM bellows; PiVAM: hydraulic pressure of the 20mL fluid; Ao: cross-sectional area of the outer iVAM bellows (Fig. 3).

The initial MEC vacuum pressure (PMEC Vac) and volume (VMEC Vac) were set to 1 atm and 27.252 cm3 (1.663 in3), and the initial iVAM vacuum pressure (PiVAM Vac) and volume (ViVAM Vac) were set to —3.5 psig and 9.652 cm3 (0.589 in3), respectively (Fig. 3). The actuation force requirement by the LDM (FLDM), which is one-eighth of the cam force (FCam) (2), over the course of 90 degrees actuator arm rotation was computed and plotted (Fig. 6A). The max actuation force against 1 atm was predicted to be 36.5 N by hand-calculations.

Fig. 6.

A) Force required to lift the actuator arm over the course of forward stroke against 1 atm. B) Work distribution projection at each component of the MEC-iVAM complex (W1: work stored in the MEC bellows; W2: work stored in the MEC vacuum space; W3: work stored in the iVAM bellows; W4: work stored in the iVAM vacuum space; and W1~W4: the sum of W1, W2, W3, and W4) during the forward-stroke.

| (2) |

E. Work Storage and Delivery

The generatable LDM force applied over the muscle shortening length (d = 32 mm) can be directly translated to the amount of energy producible by the muscle with each contraction. In this section, we compute how much of this energy will be distributed to where over the course of complete actuation cycles. One complete cycle is the sum of two phases: 1) the forward-stroke where the output fluid enters and inflates the EABP and 2) the return-stroke where the fluid exits and deflates the EABP. The total work (W) is how much contractile energy is required from the latissimus dorsi for proper EABP actuations against end-systolic pressure. A fraction of input work (W) is distributed among four different ‘storage’ sites (W1: work stored in the MEC bellows; W2: work stored in the MEC vacuum space; W3: work stored in the iVAM bellows; and W4: work stored in the iVAM vacuum space) and the EABP (W5: work delivered to the balloon) during forward-stroke (3). During the return-stroke, the stored energies work to pull the fluid back into the MEC-iVAM system.

| (3) |

Device actuation begins with lifting the actuator arm. As the actuator arm lifts, the rotary cam underneath pushes down piston A and compresses the MEC spring bellows (Fig. 3). During this forward-stroke, 0.0424 J of energy (W1) is stored in the MEC bellows (KMEC: spring constant; SMEC: stroke length of the MEC bellows over the course of forward-stroke) (4).

| (4) |

As piston A lowers, the vacuum space in the MEC housing expands, creating a negative gauge pressure within (Fig. 3). With increasing volume and decreasing pressure, 0.459 J of work (W2) is stored in the MEC vacuum space (PMEC_vac: pressure; VMEC_Vac: volume of the MEC vacuum space over the course of forward-stroke) in a form of potential energy that is later used to pull the piston A back up during the return-stroke (5).

| (5) |

Conversely, the iVAM spring bellows contributes 0.126 J of energy (W3) to the forward-stroke as it expands from its initially installed compressed state as fluid is expelled from the iVAM (Fig. 3). Accordingly, the W3 stored in the iVAM bellows (KiVAM: spring constant; SiV AM: stroke length of the iVAM bellows over the course of forward-stroke) values calculate to be negative (6) in the overall energy balance equation.

| (6) |

The expanding iVAM bellows will push down piston B and increase the volume of the iVAM vacuum space, lowering the negative pressure within (Fig. 3). This air pocket stores 0.731 J of potential energy (W4; PiV AM_Vac: pressure; ViV AM_V ac: volume of the iVAM vacuum space over the course of forward-stroke) which helps to retract the fluid from the balloon with muscle relaxation (7).

| (7) |

The remainder (W5) is delivered to the counterpulsation EABP (PEABP: pressure; VEABP : volume of the EABP over the course of forward-stroke) to actuate it against patient’s aortic end-systolic pressure during forward-stroke (8).

| (8) |

Ideally, the sum of the energy storages and delivery (W1 + W2 + W3 + W4 + W5) should equal to the total work required by the LDM (W) because totality of the five distributed energy components would either contribute to aortic compression or EABP deflation and actuator arm return. In reality, however, the sum of these compartmental energies will not perfectly match up with the total work put into the system owing to energy losses in the form of heat due to friction. The exact amount of non-recoverable energy loss will be empirically measured via bench tests. The theoretical energy distributions are compiled into a plot (Fig. 6B).

F. Material Selection

A completed muscle-powered counterpulsation system will consist of the MEC, iVAM, connecting conduit, and EABP (Fig. 7A). Heat treatable Stainless Steel (AM 350) was chosen for the MEC-iVAM body build due to its superior biocompatibility and weldability [27], [28]. The excellent corrosion resistance and high fusibility of this material combine to form a robust weld between the bellows and housing, which is essential for device durability. The high spring constant of the Stainless Steel bellows (Kss = 14.9 N/mm) also add extra resistance and flex life to the device [27], [28]. Sterile deionized water is the energy transmission fluid of choice due to its high specific heat capacity, incompressibility, low density and low viscosity, which make the system less susceptible to temperature changes, turbulent flow, and energy losses over the course of device actuation. An implantable plastic material with high biocompatibility and flexibility such as Polyurethane, Silicone, or PVC, designed to withstand pressurized fluid delivery over millions of cycles, would all be suitable for the tubing and balloon bodies. The tubing will be secured on both iVAM and EABP ends with implant-grade stainless steel band clips.

Fig. 7.

A) A 3D CAD model of a complete muscle-powered counterpulsation system (MEC-iVAM complex, connecting conduit, and EABP) isolated and B) implanted in a human thoracic cavity. The virtual model in reference to human anatomy validates comfortable fit and orientation (artificial tendon and muscle stimulator not shown).

G. Device Durability

The device, once implanted, is expected to function reliably for long-term, if not permanent, use. Engineering the bellows configurations most suitable for this extreme operational condition is the key to designing a durable device. Bellows height, width, effective area, convolution profile, and stroke length must all be carefully tuned to create appropriate volume amplification in a limited space while minimizing bellows flexion stress. The current bellows design amplifies fluid volume displacement while incorporating the minimum bellows stroke lengths possible in this design space. The durability of the bellows was examined using ANSYS finite element analyses (FEA) to quantify flex life. The life expectancy of the MEC and iVAM bellows exceed 450 million and 190 million cycles, respectively, which surpass the number of cycles considered as “infinite life” for AM 350 Stainless Steel (107 cycles) as per ASTM [27]–[29]. Therefore, the current bellows design can be rated as “fatigue-free” for an infinite life span. Other internal components, including seals, camshaft and needle bearings, were also designed for extreme wear and biochemical resistance. The durability of the spring-energized PTFE lip seals was tested in vitro using a cycling apparatus, which indicated no sign of wear throughout the test period. The only component that showed any amount of wear was the camshaft, which was very slight shown by electron microscopy [11].

III. Prototyping and Assessment

The MEC-iVAM complex (Fig. 8) was manufactured by Flex- ial Corporation (Cookeville, TN), a high-aspect-ratio welded bellows and accumulators company that specializes in industrial level engineering and manufacturing for sophisticated and complex applications. The manufactured and assembled device was then bench tested to assess its viability as a long-term VAD.

Fig. 8.

The MEC-iVAM complex manufactured and assembled.

A. Test Bench Setup

Dynamic testing of the counterpulsation system was first conducted in vitro to confirm proper system function and assess overall mechanical reliability prior to live animal trials. During this series of tests, muscular actuation was simulated via a programmable linear actuator (VLCT 45-0050-060R-AN, Animatics Inc., Elma, NY) (Fig. 9–1) attached to a smart motor (SM23216MH-EIP, Animatics Inc.) (Fig. 9–2) that features a microprocessor, servo amplifier, memory module, high capacity roller thrust bearing, and encoder. The actuator was attached to the actuator arm of the MEC (Fig. 9–3) via a thin metal chain to simulate the pull of the LDM while allowing the actuator arm to reset without assistance from the linear actuator return stroke mechanism (as is the case with muscular actuation wherein the LDM actively shortens to empty the MEC pump and passively stretches as the device fills between contractions). Motor speed and piston/MEC coupling dynamics were programmed via the Smart Motor Interface (Animatics Inc.) (Fig. 9–4) to replicate LDM actuation profiles, the primary components being a 32-mm draw over a 1/3-s ‘contraction’ period. Target speed was set to 96 mm/s at cycle rates of 60 bpm. A miniature in-line force transducer (Load Cell ELFS-T3E-250N, Entran, Edmonton, Canada) (Fig. 9–5) was placed between the linear actuator and the MEC actuator arm to monitor actuation dynamics and calculate total ‘contractile’ energy used to actuate the MEC-iVAM complex. The MEC-iVAM complex communicated with a counterpulsation EABP (C-Pulse #93020, Sunshine Heart Inc., Tustin, CA) (Fig. 9–6) via a conduit identical to the internal driveline that will be used in subsequent implant trials. The EABP was then secured around a silicone replica of the ascending aorta (Model #1454, The Chamberlain Group, Oak Brook, IL) (Fig. 9–7) made to empty into a mock circulatory system adjusted to provide mean afterload pressures from 80 to 180 mmHg using a syringe and a clamp (Fig. 9–8). The afterload in the mock aorta was monitored real-time using a Harvard pressure transducer (Model #00153, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) (Fig. 9–9). These waveforms were amplified by an amplifier module (#PS-30A, Entran) (Fig. 9–10), collected by a data acquisition system (USB-6001, National Instruments, Austin, TX) (Fig. 9–11), and recorded with LabView (National Instruments) (Fig. 9–4 to quantify MEC-iVAM/EABP coupling dynamics, determine energy transmission levels, and gauge the mechanical reliability of the actuation scheme.

Fig. 9.

Bench setup schematics for the muscle-powered counterpulsation VAD.

B. In vitro Test Results for System Accuracy and Viability

A series of assessments were performed to check if the manufactured MEC-iVAM complex meets the following requirements: 1) volume amplification for proper EABP inflation, 2) sufficient balloon actuation force against hypertension, 3) minimal balloon actuation speed for tachycardia, and 4) muscle energy distribution for energy efficient actuation cycles.

1). Volume Amplification

The measured output fluid volume ejected from the manufactured MEC-iVAM assembly (Fig. 8) was 13.68 (±0.41) mL, which was an amplification of roughly 2.73 times of the original MEC output volume. This is thought to be due, in large part, to manufacturing difficulties encountered during the fabrication of iVAM bellows convolutions (Fig. 3). Subsequent root-cause investigation revealed the pressure differentials in the iVAM vacuum space created during the inlet pressurization was large enough to have the edge welded bellows “bulge” or comply, changing the area ratio of the inner bellows and outer bellows creating the shortage in volume transfer. It is important to note, however, that although a volume amplification factor of 4 × (20 mL) was originally targeted to match the larger size C-Pulse devices used to treat adult male heart failure patients in early clinical trials, this initial 13.7 mL prototype was still able to produce clinically significant ascending aorta counterpulsation pressures in benchtop simulations [17], [18], [22].

2). Force Competency for Hypertensive Cases

Peak actuation forces against 1 atm, normal blood pressure, and hypertension pressures were empirically measured with a miniature in-line load cell placed between a linear actuator and the MEC actuator arm. The 1 atm afterload was achieved when nothing was attached at the end of the MEC-iVAM outlet port. The afterloads of normal blood pressure and hypertension were achieved by pressurizing a mock silicone aorta with a syringe plug (Fig. 10). Because the counterpulsation EABP is designed to inflate at the dicrotic notch (DN) of the aortic blood pressure waveform where the aortic valve closes, we set the DN pressure to 100 mmHg and 125 mmHg for normal and high blood pressure cases, respectively [29]–[32].

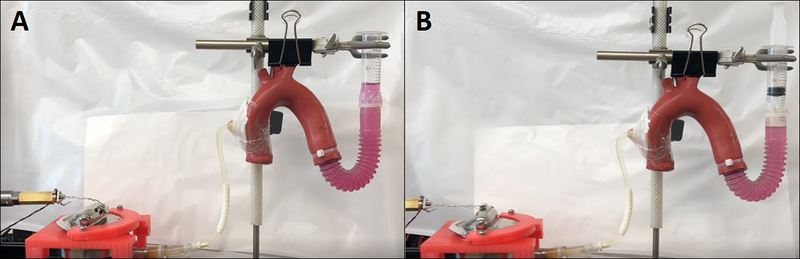

Fig. 10.

The test bench setup in rest (A) and in actuation (B) with the MEC actuator arm pulled to a 90-degree angle against a pressurized mock silicone aorta.

The measured peak tensile force (FMEC-iVAM) against 1 atm was 35.7 (±1.9) N (Fig. 11A), which is comparable with the theoretical max actuation force of 36.5 N (Δ ≅ 2.15%) that was hand-calculated in section 2.4. This test demonstrated that the tensile and contractile components (i.e., spring bellows and vacuum spaces) of the MEC-iVAM prototype performed precisely as designed. The measured peak forces against normal and high blood pressures were 73.5 (± 1.5) N (Fig. 11B) and 76.4 (±4.7) N (Fig. 11C). Considering an LDM of average mass can be trained to generate 95 N under peak sustainable power output conditions, these results (Fig. 11D) confirm that this muscle is a viable power source for chronic cardiac counterpulsation in both normal and hypertensive patients [24].

Fig. 11.

The peak MEC-iVAM actuation forces measured by a load cell placed between a linear actuator that was programmed to displace 32 mm at a speed of 96 mm/s and the MEC actuator arm that actuated against 1 atm (A), 100 mmHg (B), and 125 mmHg (C) were 35.7 (±1.9) N, 73.5 (±1.5) N, and 76.4 (±4.7) N, respectively (D)

3). Speed Competency for Tachycardia

To synchronize balloon inflation to the dicrotic notch of the aortic blood pressure waveform where the aortic valve closes while achieving complete deflation prior to the beginning of the R-wave on the electrocardiogram where isovolumic ventricular contraction begins, rapid inflation and deflation of the balloon are essential [17], [18], [22]. Since fully conditioned human LDM generates its peak sustainable power at a shortening rate of 11 cm/s, the shortest possible balloon inflation time is 0.291 seconds [24]. The measured deflation time of a hydraulic balloon attached to the outlet port of the MEC-iVAM complex was 0.136 (±0.0294) seconds, providing enough time to empty the balloon without interfering with ventricular ejection and reset the MEC-iVAM system in preparation for the next pump cycle. With this 0.427-second actuation period, the maximum cycle rate of the system (assuming a typical systolic period of 0.250 seconds) calculates to be roughly 89 bpm. This demonstrates that the actuation cycle rate of the system is applicable for both normal heart rates and cases of mild tachycardia.

4). Energy Distribution

Lastly, we assessed how LD muscle input energy was distributed during the actuation cycle. The peak force required by the LDM to actuate the system (FLDM) was quantified by measuring the tensile force when the MEC actuator arm was fully lifted to 90 degrees. Actuation force was integrated over the muscle contraction distance (XLDM) to compute the input work. The amount of energy delivered to the bloodstream was found by integrating the measured aortic pressure (PA0) over blood volume displacement (VAo). The amount of energy stored in the MEC-iVAM complex was found by integrating the actuator arm lift force (FMEC_iVAM) over the arc length of the actuator arm (XMEC-iVAM) when nothing was attached to the outlet port of the MEC-iVAM complex at 1 atm. Ideally, all of input energy should be either delivered to the bloodstream or stored in the system. But in reality, there will always be some minor miscellaneous (Misc.) energy losses due to non-conservative friction forces at the bearing sites. The theoretical energy distribution is compiled to an equation below (9).

| (9) |

Against normal blood pressure (DN: 100 mmHg), it required 0.848 (±0.032) J of energy to actuate the MEC-iVAM system, of which 0.221 (±0.0042) J was transferred to the bloodstream during balloon inflation and 0.547 (±0.0463) J was stored in the system for a rapid balloon deflation and return of the actuator arm to its original position. This indicates that 90.56 (±6.58) % of the input energy was used towards EABP actuation. Against high blood pressure (DN: 125 mmHg), it required 0.866 (±0.037) J of energy to actuate the system, of which 0.266 (±0.0014) J was delivered to the EABP and 0.547 (±0.0463) J was stored in the device. This means 93.88 (±5.86) % of the input energy was used for the EABP actuation, making our muscle-powered counterpulsation VAD an energy efficient system. The remainder was most likely contributed to various processes such as the EABP pushing against elastic aortic wall, fluid flow resistance at turbulent regions near step-down connectors between the iVAM outlet port and the balloon hose, heat energy loss due to friction during fluid travel, and measurement errors either at force or pressure gauges.

IV. Discussion

A. Does Our Prototype Meet Design Criteria?

The following seven design criteria were used to guide the development of the muscle-powered counterpulsation system: 1) anatomic fit, 2) muscle force and speed requirements, 3) work storage and delivery, 4) energy transfer efficiency, 5) material selection, 6) volume amplification, and 7) device durability. Anatomic fit was achieved by linearly stacking two already-compact devices. The MEC-iVAM complex will sit across the upper left ribcage to ensure device stability and patient comfort. The sizes and inward pressures of both EABP and securing strap should also be carefully adjusted to meet individual patient anatomic requirements and care should be taken to account for potential contraindications like aortectasia or aortic aneurysm [33]–[35]. The surgical approach and implant configuration plans are further described below. After completion of muscle force tests comparing peak actuation force requirement against high blood pressures and the LDM’s known peak sustainable force, and actuation speed requirements set by the minimum balloon inflation and deflation durations, the LDM was found to be an appropriate power source for cardiac assistance for hypertensive and tachycardiac patients. For muscle energy distribution analysis, results show that roughly 30.7% of the input energy is transmitted to the bloodstream and 63.2% is stored in the MEC-iVAM complex to power the return-strokes. Considering only about 6% of the muscle energy is lost to processes like aortic wall compression and flow turbulence, the muscle-powered counterpulsation EABP can be considered an energy efficient system. Biocompatibility of the entire system is ensured by carefully selecting implant-safe materials such as medical-grade Stainless Steel and Polyurethane for each part of the system. In regard to volume amplification, our first prototype amplifies the MEC output displacement volume by 2.73 times, yielding roughly 13.7 mL for EABP actuation. Byrefining manufacturing process of the iVAM, we will be able to produce 20 mL output volume for balloon actuation with the next prototype. Lastly, while the durability of the MEC and iVAM bellows and other internal parts, including seals and bearings, met the criteria for an “infinite” life rating, the longevity of the flexible EABP should be confirmed via cycle testing on the bench.

B. Surgical Approach and Implant Configuration

The upper left ribcage is an ideal location for MEC-iVAM implantation due to its proximity to both the LDM insertion point and the ascending aorta. Comfortable implantation and secure fixation will be achieved by placing the device across a transthoracic window created by resection of a 6.5 cm portion of one rib. The MEC suture ring will be anchored to the adjacent ribs with wire suture while the bottom two-thirds of the device will fit across and within the chest wall as shown in Fig. 7B. The outer (MEC) portion of the device will be oriented so that the direction of actuator arm rotation aligns with the direction of LDM shortening for maximum energy transfer efficiency (Fig. 7B). Inside the chest wall, the orientation of the outlet port will be arranged to stabilize the flow path and hence optimize fluid transfer efficiency between the MEC-iVAM complex and EABP. Both left and right sides of the mid-sternal line are viable options for EABP placement. Based on previous studies, the strength of fixation sites linking the device, muscle and chest wall is expected to improve and stabilize over time as fibrous tissue in-growth proceeds during the initial 2 to 4 weeks of device implantation [36]—[38].

C. Limitations

The shortage in volume amplification due to initial manufacturing limitations produces partial counterpulsation instead of the full 20 mL actuation originally targeted. Because this test was conducted with only our first prototype, this issue can be resolved when manufacturing next generation prototypes. Experimental limitations in force and pressure measurements may exist in forms of instrumental, observational, environmental, and/or theoretical errors. In an effort to minimize experimental errors, however, repeated measures design (N = 30) were used. Although the energy requirement for compressing the aortic wall in a pinching motion is expected to be miniscule, there is expected to be a small difference in wall resistances between an actual human aorta and the mock silicone aorta. This difference can be measured by repeating the test with a replaced human aorta in the future. Despite the fact that this muscle-powered counterpulsation VAD is already an energy efficient system, we can further reduce energy waste by enlarging the balloon opening, thereby eliminating the need for step-down inline connectors between the iVAM outlet port and EABP. This will significantly lower flow turbulence and frictional heat loss. Rigorous durability testing is essential for any destination therapy. Fatigue and cyclic loading of the soft polymeric EABP will be examined prior to preclinical testing.

D. Alternate Application

The MEC’s potential to drive pulsatile blood pumps extends to any form of hydraulic device designed to squeeze or otherwise manipulate the heart or aorta, preferably from the outside. One such example is a device currently under development in our lab called a soft-robotic direct cardiac compression sleeve (DCCS) [6], [8]. The DCCS is a copulsation device that would operate in synchrony with left ventricular ejection. A DCCS consists of thin-walled polymer tubing arrays that can be arranged to form a hydraulic sleeve that covers and compresses the ventricles from the outside. The mechanism of action behind this DCCS is relatively simple. When fluid enters an empty array of tubes, they transition from a flat cross-sectional configuration to a circular one, leading to decreased tube widths, and therefore, reduced sleeve diameter overall (Fig. 12A) [9]. Using this geometric advantage of tubing arrays placed side-by-side, the sleeve can induce clinically significant left and right ventricular stroke volumes when implanted in heart failure patients (Fig. 12B) [39]. This alternative means to harness endogenous muscle power for cardiac assistance will be 3D-printed using low modulus polymeric soft materials and developed in parallel with the counterpulsation system described in this paper (Fig. 12C).

Fig. 12.

Thin-walled tubes are arranged in a circle and drawn toward the center during inflation (A) to form a soft-robotic direct cardiac compression sleeve (C) that will be implanted on the epicardium of heart failure patients (B).

V. Conclusion

Whether the application is counterpulsation EABP or copulsation DCCS, the muscle-powered system serves to both reduce the risk of infection across the skin and enhance patient quality-of-life by eliminating the need for external hardware components such as extracorporeal battery packs, transmission coils, and percutaneous drivelines. Moreover, using muscle power to actuate non-blood-contacting pumps avoids thromboembolic events, and obviates the need for long-term antithrombotic therapies like anticoagulant drugs, antiplatelet agents, and routine surveillance [6]. The muscle-powered VAD would, in principle, be a more attractive option for destination therapy as it would be simpler to maintain and hence less expensive in aggregate than traditional blood pumps, thereby resulting in wider availability and reduced costs for healthcare providers.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank G. Peters, D. Benson, and S. Higbie from Flexial Corporation (Cookeville, TN) for their assistance in the design and manufacture of the iVAM device.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grant 5 R01 EB019468-02.

Contributor Information

Jooli Han, Biomedical Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213-3815 USA.

Edgar Aranda-Michel, Biomedical Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University.

Dennis R. Trumble, Biomedical Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University.

References

- [1].“Heart failure statistics,” Accessed: Aug. 04, 2019 [Online]. Available: https://www.emoryhealthcare.org/heart-vascular/wellness/heart-failure-statistics.html

- [2].Ambrosy AP et al. , “The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: Lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries,” J. Amer. College Cardiol, vol. 63, no. 12, pp. 1123–1133, Apr. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lloyd-Jones DM, “The risk of congestive heart failure: Sobering lessons from the Framingham heart study,” Curr. Cardiol. Rep, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 184–190, May 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lahpor JR, “State of the art: Implantable ventricular assist devices,” Curr. Opin Organ Transplantation, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 554–559, Oct. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Boyle A, “Current status of cardiac transplantation and mechanical circulatory support,” Curr. Heart Failure Rep, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 28–33, Mar. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Han J and Trumble DR, “Cardiac assist devices: Early concepts, current technologies, and future innovations,” Bioengineering (Basel), vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 9–10, Feb. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Trumble DR and Magovern JA, “Muscle-powered mechanical blood pumps,” Science, vol. 296, no. 5575, pp. 1967–1967, Jun. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Aranda-Michel E, Han J, and Trumble DR, “Design of a muscle-powered extra-aortic counterpulsation device for long-term circulatory support,” presented at the 2017 Des. Med. Devices Conf., 2017, Art. no. V001T01A002. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Han J, Kubala M, and Trumble DR, “Design of a muscle-powered soft robotic Bi-VAD for long-term circulatory support,” presented at the Proc. Des. Med. Devices Conf., 2018, Art. no. V001T01A003. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Trumble DR, “A muscle-powered counterpulsation device for tether-free cardiac support: Form and function,” J. Med. Devices, vol. 10, no. 2, Jun. 2016, Art. no. 020903. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Trumble DR, Norris M, and Melvin A, “Design improvements and in vitro testing of an implantable muscle energy converter for powering pulsatile cardiac assist devices,” J. Med. Devices, vol. 4, no. 3, Sep. 2010, Art. no. 035002. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Trumble DR and Magovern JA, “Linear muscle power for cardiac support: Aprogress report,” Basic Appl. Myol, vol. 9, pp. 175–186, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Trumble etal DR., “Improved mechanism for capturing muscle power for circulatory support,” Artif. Organs, vol. 29, no. 9, pp. 691–700, Sep. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kantrowitz A et al. , “Initial clinical experience with a new permanent mechanical auxiliary ventricle: The dynamic aortic patch,” Trans. Amer. Soc. Artif. Internal Organs, vol. 18, pp. 159–167, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kantrowitz A, “Experimental augmentation of coronary flow by retardation of the arterial pressure pulse,” Surgery, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 678–687, Oct. 1953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kantrowitz A, “Origins of intraaortic balloon pumping,” Ann. Thoracic. Surgery, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 672–674, Oct. 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Legget ME et al. , “Extra-aortic balloon counterpulsation: An intraoperative feasibility study,” Circulation, vol. 112, no. 9, pp. I26–31, Aug. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mitnovetski S et al. , “Extra-aortic implantable counterpulsation pump in chronic heart failure,” Ann. Thoracic Surgery, vol. 85, no. 6, pp. 2122–2125, Jun. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Izzo J, Gabbay S, and Mayott C, “In vitro testing and evaluation of intraaortic and extraaortic balloon counterpulsation devices,” in Proc.20th Annu. Northeast Bioengineering Conf, 1994, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Venturelli C et al. , “Cholesterol crystal embolism (atheroembolism),” Heart Int, vol. 2, no. 3–4, pp. 155–156, Dec. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rafieian-Kopaei M et al. , “Atherosclerosis: Process, indicators, risk factors and new hopes,” Int. J. Preventive Med, vol. 5, no. 8, pp. 927–946, Aug. 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sales VL and McCarthy PM, “Understanding the C-pulse device and its potential to treat heart failure,” Curr. Heart Failure Rep, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 27–34, Mar. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schulz A et al. , “Preliminary results from the C-Pulse options HF European multicenterpost-market study,” Med. Sci. Monitor Basic Res, vol. 22, pp. 14–19, Feb. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Trumble D, “Linear muscle power for cardiac support: Current progress and future directions,” Basic Appl. Myol, vol. 19, pp. 35–40, Jan. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gopinathannair R and Olshansky B, “Management of tachycardia,” F1000Prime Rep, vol. 7, May 2015, doi: 10.12703/P7-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bibas L, Levi M, and Essebag V, “Diagnosis and management of supraventricular tachycardias,” Can. Med. Assoc. J, vol. 188, no. 17–18, pp. E466–E473, Dec. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].“AM 350 Tech Data,”Accessed: Aug. 4, 2019 [Online]. Available: https://www.hightempmetals.com/techdata/hitempAM350data.php.

- [28].“AM-350-Stainless-Steel-Wire-UNS-S35000.pdf.” [Online]. Available: https://www.ulbrich.com/uploads/data-sheets/AM-350%C2%AE-STAINLESS-STEEL-UNS-S35000.pdf

- [29].Lloyd-Jones DM et al. , “Lifetime risk for developing congestive heart failure: The Framingham heart study,” Circulation, vol. 106, no. 24, pp. 3068–3072, Dec. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mahmud A, Hennessy M, and Feely J, “Effect of sildenafil on blood pressure and arterial wave reflection in treated hypertensive men,” J Human Hypertension, vol. 15, no.10, pp. 707–713, Oct. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Herbert J-L et al. , “Relation between aortic dicrotic notch pressure and mean aortic pressure in adults,” Amer. J. Cardiol, vol. 76, no. 4, pp. 301–306, Aug. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kamada T et al. , “Antihypertensive efficacy and safety of the angiotensin receptor blocker Azilsartan in elderly patients with hypertension,” Drug Chem. Toxicol, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 110–114, Jan. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Salibaand E Sia Y, “The ascending aortic aneurysm: When tointervene?,” Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc, vol. 6, pp. 91–100, Jan. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hong MS et al. , “Ectatic Aortas (2.5–2.9 cm) are at risk for progression to abdominal aortic aneurysm,” Ann. Vascular Surgery, vol. 34, pp. 27–28, Jul. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Elefteriades JA and Farkas EA, “Thoracicaortic aneurysm clinically pertinent controversies and uncertainties,” J. Amer. College Cardiol, vol. 55, no. 9, pp. 841–857, Mar. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Trumble DR and Magovern JA, “A muscle-powered energy delivery system and means for chronic in vivo testing,” J. Appl. Physiol, vol. 86, no. 6, pp. 2106–2114, Jun. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Trumble DR and Magovern JA, “A permanent prosthesis for converting in situ muscle contractions into hydraulic power for cardiac assist,” J. Appl. Physiol, vol. 82, no. 5, pp. 1704–1711, May 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Trumble DR and Magovern JA, “Method for measuring long-term function of muscle-powered implants via radiotelemetry,” J. Appl. Physiol, vol. 90, no. 5, pp. 1977–1985, May 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].“Ventricle-specific epicardial pressures as a means to optimize direct cardiac compression for circulatory support: A pilot study,” Accessed: Aug. 04, 2019 [Online]. Available: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0219162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [40].de Waha S et al. , “Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation — Basic principles and clinical evidence,” Vascular Pharmacol, vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 52–56, Feb. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]