Abstract

The present study investigates the cytotoxicity of hexagonal MgO nanoparticles synthesized via Amaranthus tricolor leaf extract and spherical MgO nanoparticles synthesized via Amaranthus blitum and Andrographis paniculata leaf extracts. In vitro cytotoxicity analysis showed that the hexagonal MgO nanoparticles synthesized from A. tricolor extract demonstrated the least toxicity to both diabetic and non-diabetic cells at 600 μl/ml dosage. The viability of the diabetic cells (3T3-L1) after incubation with varying dosages of MgO nanoparticles was observed to be 55.3%. The viability of normal VERO cells was 86.6% and this stabilized to about 75% even after exposure to MgO nanoparticles dosage of up to 1000 μl/ml. Colorimetric glucose assay revealed that the A. tricolor extract synthesized MgO nanoparticles resulted in ~ 28% insulin resistance reversal. A reduction in the expression of GLUT4 protein at 54 KDa after MgO nanopaSrticles incubation with diabetic cells was observed via western blot analysis to confirm insulin reversal ability. Fluorescence microscopic analysis with propidium iodide and acridine orange dyes showed the release of reactive oxygen species as a possible mechanism of the cytotoxic effect of MgO nanoparticles. It was inferred that the synergistic effect of the phytochemicals and MgO nanoparticles played a significant role in delivering enhanced insulin resistance reversal capability in adipose cells.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-020-02480-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Phytosynthesis, MgO nanoparticles, Insulin resistance, Adipose cells, Diabetes

Introduction

Plants act as a necessary food and nutrient source for humans and animals as they have the potential to acquire energy from sunlight via photosynthesis process (Cardona et al. 2018; Polat et al. 2015). Plants contain several functional secondary metabolites and bioactive compounds (Freiesleben and Jäger 2014), hence they are employed as medicinal and therapeutic agents (Wood 2017). These functional secondary metabolites are known as phytochemicals and are proven to be beneficial in biomedical applications (Kabera et al. 2014). There are numerous phytochemicals that have been extracted, characterized, and investigated for specific biomedical applications. These include phenols (Al-Brashdi et al. 2016), terpenoids (Malik et al. 2018), flavonoids (Zahid et al. 2018), carotenoids (Singh 2015), xanthophylls (Saini et al. 2018) and phytocompounds, that are specific to unique plant species (Sangeetha and Baskaran 2010; Shen et al. 2016). Phytochemicals are rich in antioxidant (Tan and Lim 2015), antimicrobial (Friedman et al. 2017), anticancer (Solowey et al. 2014), antidiabetic (Eruygur et al. 2019), anti-inflammation (Dzoyem and Eloff 2015) and antiatherogenic properties (Carluccio et al. 2003).

Diabetes has emerged as a critical metabolic deficiency amongst humans in the last decade (Zaccardi et al. 2016). There is no efficient drug entity for diabetes treatment, even with the ever-growing modern medical sciences (Buse et al. 2009), as evidenced by the recent escalation in the number of diabetic patient. Several phytochemicals extracted from plants have been used for diabetes treatment from traditional to modern medicinal practices (Oh 2015; Widjajakusuma et al. 2018). However, there are certain drawbacks, such as lack of proper documentation associated with traditional approaches (Sheng-Ji 2001) and the instability of phytochemicals in cellular environments as well as body fluids (Sivagnaname and Kalyanasundaram 2004). Thus, it is necessary to develop an alternative approach to overcome the challenges and enhance the use of phytochemicals for biomedical applications.

Biosynthesized nanoparticles are gaining more interest than conventional chemically and physically synthesized nanoparticles for biomedical applications, due to their potential to reduce undesirable cytotoxic effects (Schröfel et al. 2014). Metal nanoparticles, particularly metal oxide nanoparticles, are identified to be beneficial in various pharmaceutical applications due to their structural stability (Singh et al. 2016; Singh 2017). Moreover, synthesizing metal oxide nanoparticles via biological approaches, further enhances their bioactivity, biocompatibility and bioavailability (Pereira et al. 2015). Recently, bacteria (Singh et al. 2015), fungi (Amerasan et al. 2016) and plant (Hanan et al. 2018) mediated synthesis methods have been developed for the synthesis of metal oxide nanoparticles. However, bacterial and fungal synthesis methods possess limitations, such as extended metabolic processes and scale-up difficulties (Jeevanandam et al. 2016). Thus, phytosynthesis approach has gained significant attention amongst researchers in metal oxide nanoparticle synthesis for exclusive biomedical and pharmaceutical applications (Andra et al. 2019). Amongst metal oxide nanoparticles, magnesium oxide (MgO) nanoparticles are reported to be useful in the applications, such as cancer treatment (Krishnamoorthy et al. 2012), nanocryosurgery (Di et al. 2012), antimicrobial formulations (Leung et al. 2014) and tumor imaging (Dowsett and Wirtz 2017). This is due to its high biostability, bioactivity and bioavailability with less cytotoxicity and genotoxicity (Liu and Webster 2016; Mirhosseini and Afzali 2016).

Magnesium has been incorporated into various treatment strategies for diabetes (Petrak et al. 2015; Simental-Mendía et al. 2016; Whitfield et al. 2016). Several studies have reported that magnesium level and insulin resistance are indirectly proportional, and hypomagnesemia leads to diabetes complications (Bertinato et al. 2015; Kurstjens et al. 2017). Thus, magnesium supplements are used routinely to restore insulin resistance and reduce complications in patients (Asemi et al. 2015). Also, we have previously reported that chemical synthesized MgO nanoparticles as magnesium supplement has the ability to reverse insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes (Jeevanandam et al. 2015, 2019b). In line with this, the effect of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles in reversing insulin resistance is investigated in the current study. MgO nanoparticles are synthesized using Amaranthus blitum, Amaranthus tricolor and Andrographis paniculata. Since the aqueous extracts of these plants are rich in phytochemicals and demonstrated to possess antidiabetic activities, the present study aims to demonstrate the insulin resistance reversal ability of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles via in vitro cytotoxic and diabetic analysis. Additionally, the molecular mechanisms responsible for cytotoxicity and insulin resistance reversal ability are discussed.

Experimental procedure

Extraction of crude phytochemicals

Amaranthus blitum, Amaranthus tricolor and Andrographis paniculata are the plants used in the current study and were purchased from the local market in Miri, Sarawak, Malaysia. A detailed description of the extraction procedure is provided in our previous work (Jeevanandam et al. 2017c). The fresh plant leaves were collected, cut into smaller pieces, and washed in distilled water several times. The leaves were suspended in distilled water (1:10 w/v) and heated at 100 °C for 20 min to extract phytochemicals. The crude extracts were cooled to room temperature, filtered using a mesh and Whatman No.1 filter paper to eliminate impurities and solid particles. The filtered crude leaf extracts from all the three plants were stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C for nanoparticle synthesis.

Synthesis and characterization of MgO nanoparticles using plant leaf extracts

The crude, aqueous leaf extracts stored at 4 °C were added to magnesium nitrate hexahydrate (98%), purchased from Alfa Aesar® (USA), and heated at 60 °C for 10 min for the synthesis of MgO nanoparticles. The optimized process parameters from our previous work was utilized to generate defined MgO nanoparticle size (Jeevanandam et al. 2017c). The synthesized nanoparticles were characterized using UV–visible spectrophotometric measurements (Perkin Elmer® Lambda 25) and dynamic light scattering analysis (Malvern® Zetasizer Nano ZS). The colloidal MgO nanoparticles were by freeze-dried using Fisher brand Labconco* 1.5L Freeze dry system under 0.133 mBar vacuum at − 40 °C. The freeze-dried MgO nanoparticle samples were characterized using Fourier transform infrarRed spectroscopy (Thermo scientific model NICOLET iS10) and transmission electron microscopy (Tecnai™ G2 Spirit BioTWIN, FEI Company) to reveal the existence of surface functional groups and morphology, respectively.

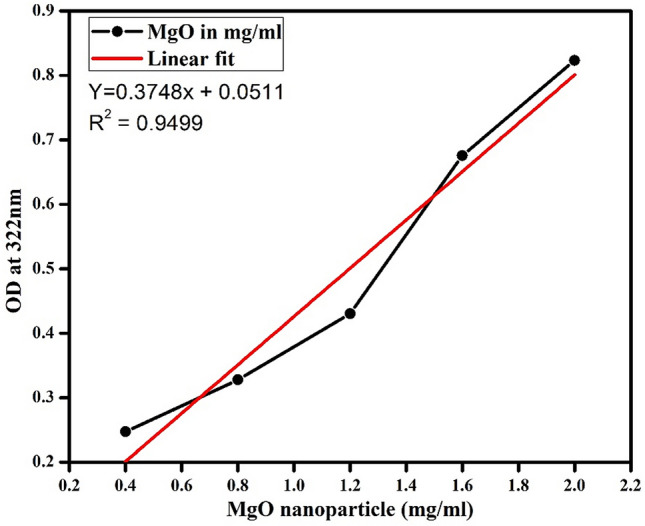

Concentration of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles

The concentration and type of phytochemicals present in each plant species can vary, and this may affect the size and quantity of nanoparticles generated. Thus, it is necessary to quantify the concentration of MgO nanoparticles, that are synthesized from each plant leaf extracts. Spherical shaped, chemically synthesized MgO nanoparticles from our previous work (Jeevanandam et al. 2017b) was used to develop MgO concentration calibration curve as shown in Fig. 1. The absorbance value of the phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles at 322 nm was used to determine the concentration of MgO nanoparticles from the different plant extracts as shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Calibration curve to determine MgO nanoparticle concentration. Different concentrations (0.4–2 mg/ml) of MgO nanopowders were dissolved double distilled water and obtained an OD value at 322 nm wavelength and its subsequent linear fit equation for the determination of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticle concentration

Table 1.

Concentration of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles from different plant leaf extracts

| Sample | Absorbance at 322 nm | Concentration (mg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Sample A | 0.26 | 0.56 |

| Sample B | 0.39 | 1.08 |

| Sample C | 0.33 | 0.82 |

*Sample A—MgO nanoparticles prepared using magnesium nitrate and A. tricolor leaf extract; sample B—MgO nanoparticles prepared using magnesium nitrate and A. blitum leaf extract; and sample C—MgO nanoparticles prepared using magnesium nitrate and A. paniculata leaf extract

*Sample A–MgO nanoparticles prepared using magnesium nitrate and A. tricolor leaf extract; sample B—MgO nanoparticles prepared using magnesium nitrate and A. blitum leaf extract; and sample C—MgO nanoparticles prepared using magnesium nitrate and A. paniculata leaf extract.

Chemicals and reagents for cell line studies

Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Other reagents such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 10 × at pH 7.4, penicillin and streptomycin antibiotics, and trypsin–ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA) were purchased from Thermo Fisher scientific company (USA).

Culturing procedures for diabetic and non-diabetic cells

3T3-L1 adipose and VERO kidney epithelial cell lines were purchased from National Cell Culture Society (NCCS) repository, Pune, India. The 3T3-L1 cells were cultured to modify them into mature, insulin-resistant adipose cells (McGillicuddy et al. 2011), and the modified adipose cells are used as the diabetic cell model in the present study. The 3T3-L1 cells were initially cultured in DMEM growth medium with 3.65 mg/ml of glucose and 10% FBS. Later, the cells were differentiated into adipocytes using DMEM differentiation medium with 5 µg/ml of insulin. The cells were grown in the differentiation medium for 72 h and then in the growth medium with 1 ng/ml of insulin for 48 h. Finally, the media was changed to serum-free DMEM containing 2% heat-inactivated FBS and 1 g/L of glucose for 24 h to transform them into insulin-resistant cells before each experiment (Adochio et al. 2009; Elmendorf et al. 1998). The VERO cells were cultured in a liquid medium mixture of DMEM, 10% FBS, streptomycin (100 μg/ml) and penicillin (100 U/ml) in favorable humidified atmospheric condition at 37 °C in a T75 flask. 1 × PBS was used to wash the cells, and the cells attached to the sides of the T75 flask were detached by trypsin–EDTA solution. The cells reached 60% confluency in 3 days and were passaged into a T25 flask after the washing process with PBS and trypsin–EDTA solutions on the fourth day for secondary culture. These VERO cells were used as the normal, non-diabetic cell model in this present work. All analyses were performed between 3rd and 10th passage. The cell morphology and counts were determined using a Compound microscope (OMAX 40–2000 × digital lab LED binocular compound microscope).

MTT assay

The cytotoxicity of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles was determined via a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. The conversion of MTT into formazan crystals with the help of mitochondrial dehydrogenase is the principle behind the MTT assay. MTT assay is used to estimate the cytotoxicity of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles in both diabetic and non-diabetic cells (Carmichael et al. 1987; Mosmann 1983). The MTT dye was purchased from Sisco Research Laboratories Pvt. Ltd. (SRL—India). The cells were maintained at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 1 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates. 200–1000 µl of MgO nanoparticle samples were added to the cell culture and incubated for 24 h. After 24 h, the cells were cleaned with PBS at pH 7.4. The cells were then added to 100 μl of 0.5% MTT dye (5 mg/ml) per well and incubated for 4 h. 1 ml of DMSO was added to each well after incubation. A microplate reader was used to measure the absorbance of DMSO at 570 nm as the blank, and cell viability was determined using Eq. 1. The experiments were performed in triplicate and the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The dosage required for 50% inhibition of cells (IC50) was calculated by linearly fitting the concentration–response curve, as shown in supplementary material sections S.1 and S.2.

| 1 |

The phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles were subjected to react with matured 3T3-L1 adipose (diabetic) cell lines and analyzed for cytotoxicity using MTT assay. The cells were treated with different dosages of 200, 400, 600, 800 and 1000 μl/ml of colloidal MgO nanoparticles for 24 h to identify the maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50). To establish uniformity in the cell viability studies, the dosage in µl/ml is used instead of the final concentration as it will be difficult to compare the cytotoxicity and viability data. The use of µl/ml has previously been used for cytotoxicity studies (Karaman et al. 2017; Meselhy et al. 2018; Shehzad et al. 2018). The concentrations of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles in the sample dosages are presented in the supplementary material section (Table S.8).

Colorimetric glucose assay

All chemicals and reagents used in the glucose assay, including dinitro salicylic acid (DNS), were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich® (USA). A standard calibration curve with pre-quantified glucose was obtained as shown in supplementary section S.3. following the experimental procedure reported by (Mohamed et al. 2009). DNS-based colorimetric glucose assay was performed to determine the cellular glucose levels before and after 600 μl/ml of sample A treatment for 25 h to investigate insulin resistant reversal in diabetic cells. 0.025 M (450 mg) of glucose was mixed with 100 ml of distilled water to prepare a standard glucose stock solution. A 0.2–1 ml aliquot of the stock solution was added in a test tube and was made to the final volume of 2 ml with distilled water. The diluted glucose solution was mixed with 1 ml of DNS reagent and the mixture was incubated in a boiling water bath for 5 min. Finally, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and the optical density was measured at 540 nm using a portable UV–visible spectrometer (Hitachi U-3900H UV–Visible spectrophotometer). A similar procedure was followed to estimate the quantity of intracellular and extracellular glucose. Matured insulin-resistant 3T3-L1 cells were plated with DMEM medium and 10% FBS in a 6-well plate under a humidified atmosphere of CO2 (50 μg/ml), and was placed in an incubator at 37 °C for 24 h. Insulin-resistant cells were challenged with 20 µM/ml of insulin for 15 min. After every 5 h of incubation, the control DMEM medium (without loading nanoparticle) and the nanoparticle-loaded cells (selected dosage, n = 3) were subjected to colorimetric analysis. After 24 h, the medium was washed, a mixture of 1 × PBS and 10% SDS was used to lyse the cells, and the lysed cells were removed. The quantity of extracellular and intracellular glucose present in the insulin-resistant cells after 24 h was used to determine the total glucose. The total glucose in the control sample was compared with the nanoparticle-loaded samples to evaluate the insulin resistance reversal ability of the phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles.

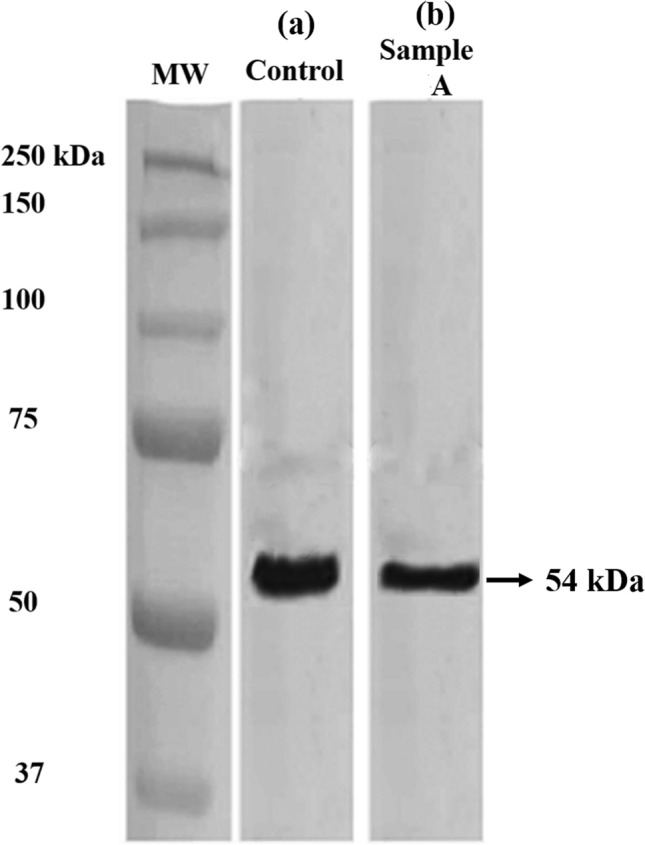

Estimation of GLUT4 protein

Western blot analysis was used to estimate GLUT4 protein expression in the diabetic cells. All the chemicals and reagents used for the western blot analysis were procured from Sigma-Aldrich® (USA). Diabetic cells were collected and rinsed twice with 10 × PBS, after 1 × 105 cells/ml were incubated with the nanoparticles for 24 h. A lysis buffer of 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 250 mM NaCl and 100 mM Tris–HCl was used to lyse the cells under sonication at 4 °C and pH 8 for 30 min. Centrifugation of the lysed cells was performed for 25 min at 4 °C of 13,000 × RPM and the supernatant were stored for further use as the expressed GLUT4 protein sample. An aliquot of the lysed cells was analysed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; 40 µl per well) with loading control (actin) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. A 5% of non-fat dried milk was used to block the proteins. A primary anti-GLUT4 antibody was incubated with the membrane for 2 h and an anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody was incubated with the membrane for 30 min. Finally, the western blot detection system (ChemiDoc™ MP) was used to detect the protein bands. Section S.4. of supplementary materials contain additional information on the western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed with the control and nanoparticle treated cells to identify the expression of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) proteins. GLUT4 is a protein present in the cytoplasm of adipose cells. In healthy normal cells, GLUT4 is expressed on the plasma membrane of the cells after insulin binding to its substrate, eventually facilitating glucose uptake into the cells from the extracellular matrix (Cushman and Wardzala 1980). Thus, the plasma membrane and cytoplasmic vesicular are the two main regions, where GLUT4 protein is present in the cells. In this study, the cytoplasmic vesicular GLUT4 was obtained via centrifugation of the diabetic adipose cells, and western blot analysis of the supernatant was performed. The anti-GLUT4 antibody used for the western blot does not detect plasma membrane GLUT4 at 54 kDa, as it binds with the lipid bilayer of adipose cells and increases their molecular weight (Martin et al. 2006; Stöckli et al. 2011).

Analysis of cell–nanoparticle interaction

Similar to the western blot analysis, the cells (1 × 105 cells/ml) were incubated with the nanoparticle samples for 24 h in a 6-well plates, and 1xPBS buffer was used to rinse the cells. A fluorescence microscope was used to image the stained cells and cell organelles, such as liposome, to investigate cell-nanoparticle interactions. The cells were treated with 0.2 ml of propidium iodide (10 μg/ml) for 30 min and fixed in a cover slip using 70% ethanol (ACROS Organics). Stained cells in the cover slip were removed from the 6-well plate and placed in a grease free glass slide. Fluorescence microscope (40–1000 × infinity plan EPI Fluorescence microscope FM800TC) was used to image the stained cells. Following the same protocol, 0.2 ml of acridine orange (10 μg/ml) dye was also used to stain the cells. Propidium iodide and acridine orange dyes were used in fluorescence microscopic analysis to investigate the interaction between adipose cells and phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles. Propidium iodide dye helps to analyze nanoparticle-mediated disruption of cell membrane and DNA (Riccardi and Nicoletti 2006). The acridine orange dye emits green color after binding onto viable cells, and this is used to analyze the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by MgO nanoparticles. The release of ROS into cells increases intracellular acidity, which is visualized as an orange color.

Results and discussion

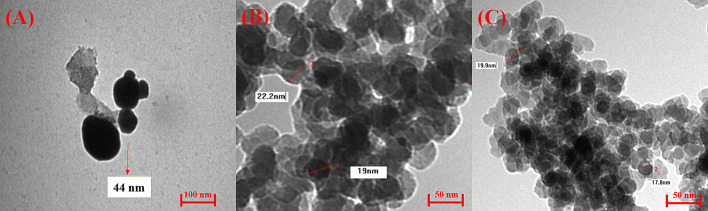

The phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles selected for cytotoxicity analysis in the present study were based on our previous work that focused on in-depth characterization of MgO nanoparticles (Jeevanandam et al. 2017a). Table 2 presents a summary of the relevant physicochemical properties of MgO nanoparticles. Sample A contained both hexagonal and spherical shaped nanoparticles at pH 7 of aqueous solution. However, the morphology was transformed to mostly hexagonal by altering its pH to 3 (Jeevanandam et al. 2019a). The other two samples were spherical at pH 7 (Jeevanandam et al. 2017c). The morphologies of all three samples are shown in Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Physico-chemical characteristics of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles

| Sample | Precursor | Leaf extract | pH | Surface charge (mV) | Morphology | Size (nm) ± PDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample A | Magnesium nitrate | Amaranthus tricolor | pH 3 | − 3.39 | Hexagon | 44 ± 0.454 |

| Sample B | Magnesium nitrate | Amaranthus blitum | No pH modification (pH 7) | − 15.4 | Spherical | 25 ± 0.351 |

| Sample C | Magnesium nitrate | Andrographis paniculata | No pH modification (pH 7) | − 11.4 | Spherical | ~ 20 ± 0.558 |

Fig. 2.

TEM micrograph of MgO nanoparticles phytosynthesized using a A. tricolor (sample A) (Jeevanandam et al. 2019a); b A. blitum (sample B) and c A. paniculata (sample C). Reproduced with the permission from (Jeevanandam et al. 2017c),

© The Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) on behalf of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS)

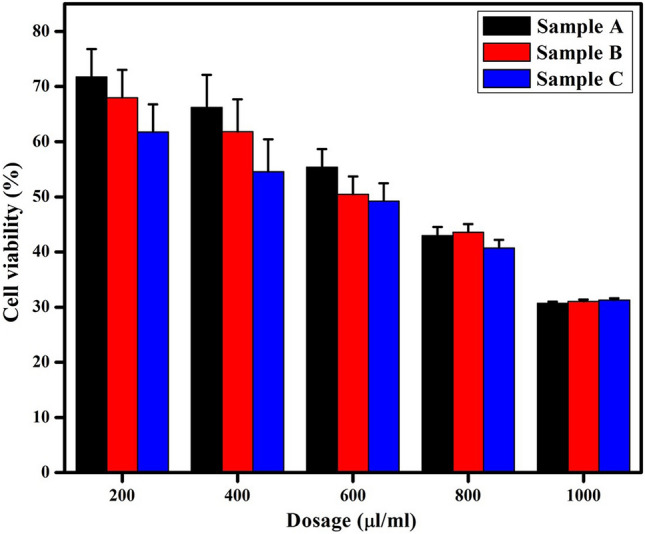

Cytotoxicity analysis of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles in diabetic cell lines

Figure 3 compares the percentage of viable cells after MgO treatment over a 24 h incubation period and shows a decrement in the viability of cells with an increment in the concentration of MgO nanoparticles. This reduction in cell viability can be attributed to increasing interstitial fluid pressure due to the presence of higher nanoparticle concentration per unit cell interaction, potentially damaging the cytoplasm and leading to cell death (Blanco et al. 2015; Pakrashi et al. 2014). In addition, the presence of high MgO nanoparticle concentrations can interrupt and/or block transmembrane molecular transport mechanisms, that are necessary to support cellular activities, and this may result in decreasing the cell viability. IC50 concentration was achieved at 600 μl/ml of dose for all the three samples. However, a slightly higher cell viability (55%) is observed in the sample A at the IC50 concentration, compared to samples B and C. The slightly higher cell viability can be attributed to the presence of edge surface atoms in the hexagonal-shaped nanoparticles of sample A, which possess ability to reduce potential biophysical effects and uniformity of reactive cell membrane exposure.

Fig. 3.

The viability of adipose cells after treatment with samples A, B and C of MgO nanoparticles at varying dosages showing dose dependent toxicity of nanoparticles with IC50 at 600 μl/ml

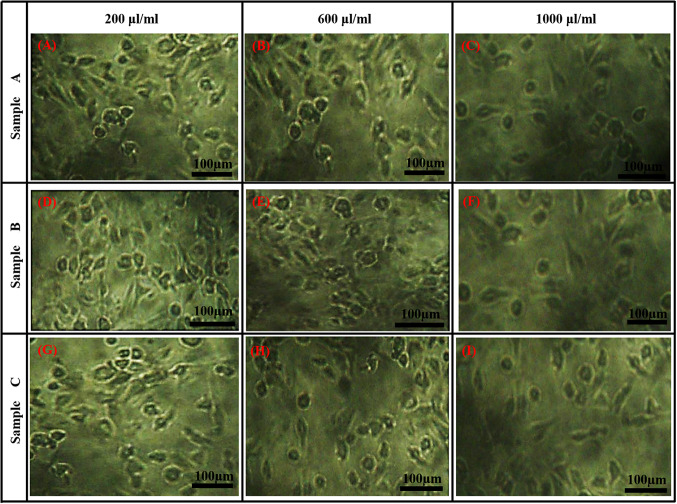

The morphological images of the diabetic cells after treatments with the phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles samples at low (200 μl/ml), mid (600 μl/ml) and high (1000 μl/ml) dosages are shown in Fig. 4. The micrographs revealed that all the MgO nanoparticle treated cells has led to dosage-mediated morphological changes in the adipose cells. The fibroblast morphology of the cells undergoes transformation into spherical forms, when the dosage of MgO nanoparticle is increased. Generally, mature 3T3-L1 cells are fibroblast in morphology, which undergoes stress, especially in cell membranes, due to the addition of nanoparticles and transforms into irregular shapes, depending on the dosages (Borenfreund and Puerner 1985). Kim et al. (2015) also showed that the cellular morphology of NIH/3T3 fibroblast transforms due to the addition of higher silica nanoparticle concentration, indicating an increase in cytotoxicity (Kim et al. 2015). Thus, this may partly explain the increase in cell death at higher dosages of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles. In addition, the surface charge of MgO nanoparticles may also be a reason for the reduced cytotoxicity of hexagonal MgO nanoparticles (sample A). The surface charge of sample A was − 3.39 mV, closer to neutral stability compared to sample B (− 15.4 mV) and sample C (− 11.4 mV). Slightly negative or neutral surface charged particles have an extensive circulation period and inferior cellular accumulation due to their low adsorption capacity towards proteins, and this reduces nanoparticle-mediated cytotoxicity (Alexis et al. 2008; Xiao et al. 2011; Yamamoto et al. 2001). Thus, hexagonal-shaped sample A was selected for further analysis, as lowest cytotoxic effect was observed in this sample.

Fig. 4.

Micrograph of 3T3-L1 cells after treatment with phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles samples A, B and C, which reveals the alterations in the morphology of 3T3-L1 fibroblast cells due to the presence of nanoparticles

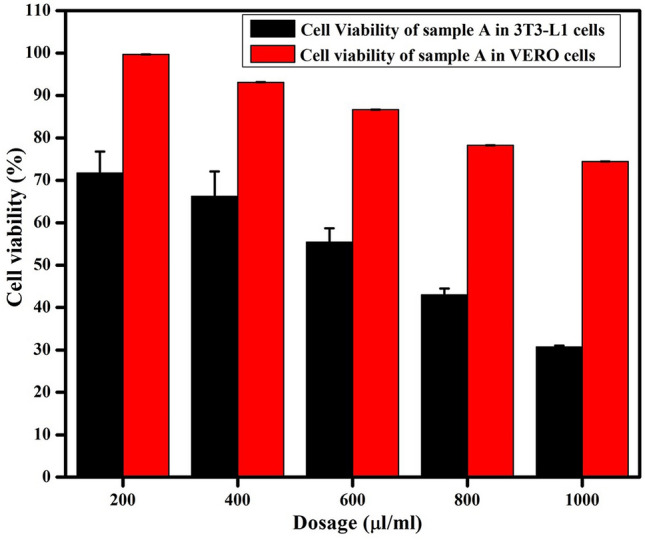

Cytotoxicity analysis of phytosynthesized hexagonal shaped MgO nanoparticles in non-diabetic cell lines

Comparative cytotoxicity analysis was performed using VERO and 3T3-L1 cells treated with varying dosages of sample A. Figure 5 shows that, overall, the viability of VERO cells is higher than 3T3-L1 cells after 24 h treatment with sample A. The viability of VERO cells is ~ 75%, even at a higher sample A dosage of 1000 μl/ml. The lower cytotoxicity of the nanoparticles towards normal, non-diabetic cells can be attributed to the selective bioavailability of hexagonal-shaped MgO nanoparticles with phytochemicals as functional groups and capping agents (Swarnakar et al. 2014). The comparative cytotoxicity analysis reveals that the phytosynthesized hexagonal MgO nanoparticles are less toxic towards non-diabetic cells than the diabetic cells. Chan et al. (2015) investigated the cytotoxicity of A. tricolor phytochemicals extracted using six different chemicals (hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, ethanol, methanol, and water). They reported that, apart from the ethyl acetate extract of A. tricolor, the phytochemicals from all the other extracts showed VERO cell viability via MTT assay (Chan et al. 2015), which is in keeping with the findings of the present work. Similarly, the cytotoxicity of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles is effectively reduced towards both normal and diabetic cells, compared to nanosized MgO particles fabricated via sol–gel-based chemical approach (Jeevanandam et al. 2019b). Thus, it can be inferred that the phytochemicals present in A. tricolor such as flavonoids (Bai et al. 2017), terpenoids (Boo et al. 2018), amaranthine (Chyau et al. 2018) and phenols (Aranaz et al. 2019), are not only responsible for nanoparticle synthesis, but also for cytotoxicity reduction in normal, non-diabetic cells. The synergistic effect of phytochemicals that are capped over MgO nanoparticles are responsible for the reduction of cytotoxicity (Andra et al. 2019). In addition, the phytochemicals may function as nutritional or selective functional ingredients that support cell growth. The findings also support that the selected phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles possess the potential to be beneficial as a nanomedicine candidate for diabetic treatment with reduced side-effects towards normal cells. Thus, 600 μl/ml dosage level (0.58 mg/ml of nanoparticles; more information in supplementary material table S.8) is selected for further diabetic studies and the selection is based on the IC50 concentration of the sample A in diabetic cells, as ~ 87% of non-diabetic cells are viable at the same dosage.

Fig. 5.

Comparative cell viability analysis after treating diabetic (3T3-L1) and non-diabetic (VERO) cell lines with varying dosages of sample A, showing that the hexagonal MgO nanoparticles are less toxic towards non-diabetic cells

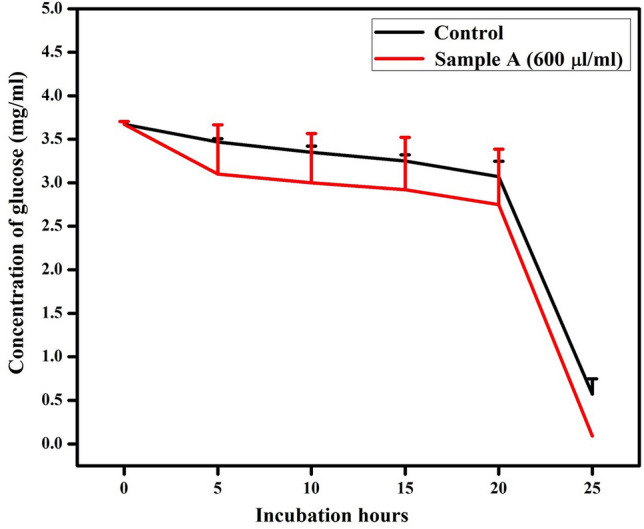

Insulin resistance reversal analysis via colorimetric glucose assay

The concentrations of intra and extra-cellular glucose are shown in Fig. 6. The data indicate the presence of ~ 3.7 mg/ml of glucose in the insulin-resistant control cells, which slowly decreases as the cells utilize glucose to support their growth. The reduction in glucose concentration depends on the insulin resistance level of the diabetic cells (Houstis et al. 2006). Thus, it can be noted that 0.57 mg/ml of glucose is present, as the extracellular glucose, in the diabetic cells after 24 h. On the other hand, the nanoparticle treated sample showed an increased glucose uptake and reduced extracellular glucose more than the control cells. It is noteworthy that only 0.09 mg/ml of residual extracellular glucose remained in the nanoparticle treated cells after a day. The sudden drop in the extracellular glucose concentration after 20 h in both the control and nanoparticles treated cells was attributed to the activity of poly (ADP-Ribose) synthetase (PARS) (Luo et al. 2017). PARS is a nuclear enzyme that is predominantly present in eukaryotic cells, covalently bound to several proteins in cellular nucleus and participates in DNA synthesis, repair and cell differentiation (Kameshita et al. 1984; Liaudet et al. 2001). The secretion and activation of PARS depend on the ATP production and glucose uptake in the cells (Du et al. 2003; Szabó and Dawson 1998). Hence, the constant glucose uptake until 20 h would have activated PARS, which leads to higher glucose uptake after 20 h and utilize them for cell differentiation and DNA synthesis.

Fig. 6.

Time-dependent glucose reduction profiles for control cells and phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles treated cells at a dosage of 600 μl/ml

The intracellular glucose concentration was determined using the control and nanoparticle-loaded sample after 24 h. The control cells had 0.71 mg/ml of glucose, whereas 0.017 mg/ml of glucose was present in the nanoparticles treated cells as shown in Table 3. Glucose uptake analysis revealed that the control cells utilized about ~ 67% of glucose, while the presence of MgO nanoparticles increased glucose uptake, resulting in ~ 93% glucose utilization in the diabetic cells. It can be inferred that the phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles possess ability to increase glucose uptake by ~ 28% in diabetic cells by reversing insulin resistance via activation of certain enzymes (Jeevanandam et al. 2015, 2019b). It has been reported that the fat-derived adiponectin hormone possess ability to reverse insulin resistance (Yamauchi et al. 2001). This hormone is secreted by the activation of enzymes, especially 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (Lihn et al. 2005). Likewise, glucose transporter-4 (GLUT-4), which is an insulin-sensitive transporter, can also facilitate glucose uptake in adipose tissues. When the insulin concentration is low in cells, due to insulin resistance, phosphatidylinositol phosphates are formed by phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), that are activated by tyrosine kinase to elevate glucose uptake (Smith and Morton 2010). Previous literatures revealed that the magnesium ions have the ability to activate both these enzymes in preadipocytes (Ha et al. 2016; Lee et al. 2015; Yang et al. 2000). Hence, it has been proposed in the current study that the magnesium ions from the nanoparticles may activate these enzymes, which may have subsequently activated GLUT-4 to increase glucose uptake. In addition, Rahmatullah et al. (2013) also showed that the methanolic whole plant extract of A. tricolor possessed antihyperglycemic properties, enabled enhanced glucose uptake and reduced serum glucose level in diabetic rats (Rahmatullah et al. 2013). Their finding further strengthens the enhanced glucose uptake property of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles as demonstrated in the present work.

Table 3.

Total glucose and glucose uptake levels in control and nanoparticles treated sample after 24 h

| Sample | 0 h mg/ml |

After 24 h mg/ml |

Total glucose (extra + intra cellular glucose) mg/ml |

Glucose utilization by cells after 24 h (%) | Difference in glucose uptake compared to control cells (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In medium (extracellular glucose) | Inside cells (intracellular glucose) | |||||

| Control | 3.67 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 1.22 | 66.75 | – |

| Sample A | 3.67 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 92.9 | 28.1 |

GLUT4 protein estimation

The image in Fig. 7 shows a wider and more intense protein band of the control cells, whereas the nanoparticle-treated cells has a less intense protein band. The GLUT4 protein is located in the cytoplasmic vesicles of adipose cells, due to the insulin resistance mediated inhibition of the binding mechanism between insulin and their respective receptor. Figure 7a shows that the control cells are insulin resistant with a wide and more intense protein band at 54 kDa, indicating the presence of cytoplasmic GLUT4 (Sylow et al. 2013, 2014). However, Fig. 7b shows a smaller width and less intense protein band for the nanoparticle treated sample due to the reversal of insulin resistance. This finding supports the result from DNS glucose assay and demonstrates insulin resistance reversal by the MgO nanoparticles, further increasing the efficacy of insulin-receptor binding. This binding between insulin and its receptor leads to a cascade event of cytoplasmic protein to be expressed on the plasma membrane, increasing glucose uptake and reducing the quantity of cytoplasmic GLUT4 protein as well as the glucose level (Martin et al. 2006). Naveen and Baskaran (2018) reported numerous phytochemicals including amaranth, with the potential to increase the expression and translocation of GLUT4 in adipose cells and reduce blood glucose level (Naveen and Baskaran 2018). Hence, the western blot analysis supports the insulin resistance reversal ability of the phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles.

Fig. 7.

Estimation of GLUT4 protein expression in a control and b Sample A, showing the reduced expression of GLUT4 protein in sample A incubated cells, compared to control indicating the insulin resistance reversal ability of MgO nanoparticles

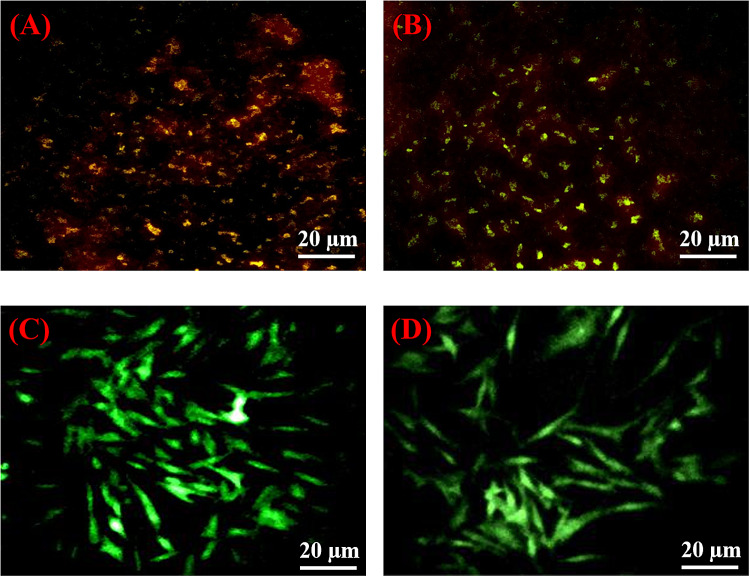

Investigation of cell-nanoparticle interaction

Figure 8a, b are the fluorescence microscopic images of the control and nanoparticle treated cells. The images were modified with ImageJ software to enhance the intensity of the contrast. The yellow stains in the image represent membrane disrupted, non-viable cells. It is evident from Fig. 8b that the nanoparticle-treated cells possess comparatively more yellow stains than the control cells in Fig. 8a, and this supports the cytotoxicity level of MgO nanoparticles as revealed by the MTT assay. Figure 8c, d showed the presence of viable cells in both the control and nanoparticle treated cells. Both the images exhibited a green fluorescence, indicating that there is no significant effect of nanoparticle-mediated ROS release, suggesting that the MgO nanoparticles are bound to the cell membrane of the adipose cells.

Fig. 8.

Fluorescence microscopic images of propidium iodide stained 3T3-L1 cells after 24 h a control cells, b cell treated with 600 μl/ml of MgO nanoparticles and acridine orange stained 3T3-L1 cells after 24 h c control cells and d cells treated with 600 μl/ml of MgO nanoparticles

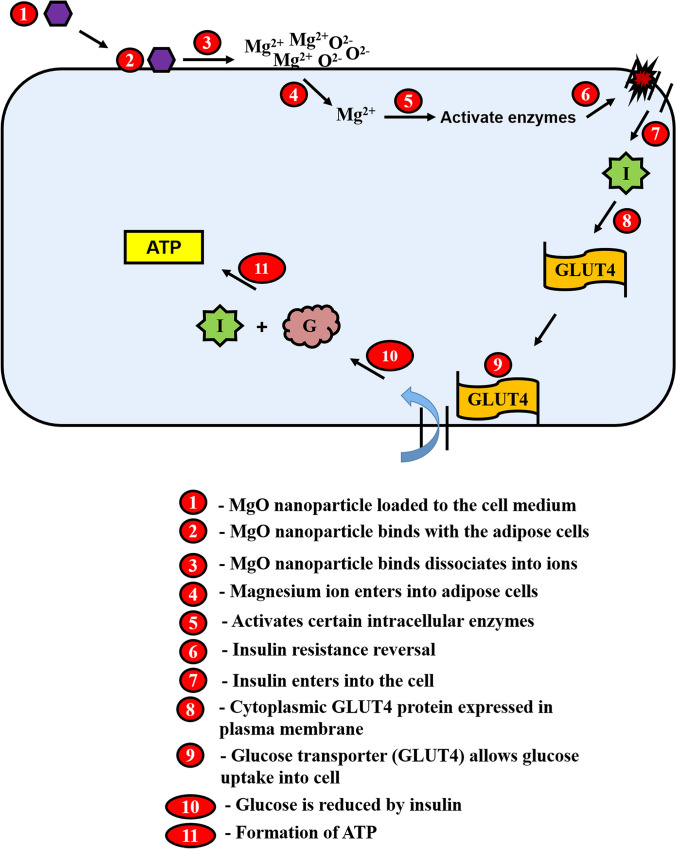

Proposed mechanism of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles in reversing insulin resistance

Figure 9 is a schematic representation of the proposed mechanism for insulin resistance reversal in adipose cells by the phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles. The MgO nanoparticles are loaded onto the adipose cells and are attracted towards the cell membrane by electrostatic force of attraction. Adipose cells possess lipid molecules on the cell surface that contain positively charged polar molecules (Edidin 2003) and these attract negatively charged MgO nanoparticles. The attachment of the nanoparticles to the cell surface induces polarization into ionic states (Yameen et al. 2014), such as magnesium and oxygen ions. Further, the magnesium ions permeate the cellular ionic channels, enters into the cell and activates intracellular enzymes, such as PARS, AMPK and PI3K, to reverse insulin resistance (Monteilh-Zoller et al. 2003). Meanwhile, the oxygen ions act as ROS and induce hydrogen peroxide formation that elevates extracellular oxidative stress and disrupts the cell membrane (Premanathan et al. 2011; Simon et al. 2000). The activation of specific enzymes supports the biofunctional capabilities of selective bioavailability and toxicity of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles towards adipose cells.

Fig. 9.

Schematics of the proposed mechanism of reversing insulin resistance in adipose cells. The stages of insulin resistance reversal by MgO nanoparticles may include: 1. diabetic adipose cells incubated with MgO nanoparticles, 2. nanoparticle binds to the cells, 3. dissociation of ions from nanoparticles, 4. internalization of magnesium ions into cells, 5. activation of intracellular enzymes, 6. reverses insulin resistance, 7. entry of insulin into the cells, 8. cytoplasmic expression of GLUT4 protein in plasma membrane, 9. GLUT4 allows glucose uptake into cells, 10. glucose reduction by insulin and 11. ATP formation in cells

The reversal of insulin resistance by magnesium ions allow insulin to enter the cell, eventually leading to the expression of cytoplasmic GLUT4 and its translocation towards the cell membrane (Favaretto et al. 2014). This explains the reduction in the concentration of cytoplasmic GLUT4 protein, that are observed in the nanoparticle treated cells via the western blot assay. The translocated GLUT4 signals glucose to enter into the cell and this increases glucose uptake from the nutrient growth medium, where the intracellular glucose is reduced to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) with the help of insulin. This explains the increased extracellular and intracellular glucose uptake in the nanoparticle treated adipose cells after 24 h based on the glucose assay. Thus, it is worthy to note that the phytochemicals play a crucial role in GLUT4 targeting and determining biophysical characteristics of nanoparticles, including morphology, surface charge, and electrostatic attraction towards adipose cells.

In summary, the present work demonstrated that the phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles possess the ability to reverse insulin resistance in diabetic cells. It represents a premier study focused on evaluating the characteristics of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles as a less toxic, stable drug entity for reversing insulin resistance in diabetic cells. This study shows that the generation of nanoparticles with phytochemicals as functional groups and capping agents exhibit a synergistic effect in reversing insulin resistance in diabetic cells with low toxicity. We have utilized simple biological assays, such as MTT assay, DNS glucose assay, western blot and fluorescence microscope to provide initial evidence of the insulin resistance reversal ability of phytochemical capped MgO nanoparticles. Whilst more analytical work can be done to further demonstrate the insulin resistance reversal characteristics of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles, the present work has sufficient preliminary data as an initial step to support the insulin resistance reversal properties of MgO nanoparticles, which would spark research interest towards the development of MgO-based nanomedicines for diabetes treatment.

Conclusion

The present work examines the cytotoxicity of MgO nanoparticles phytosynthesized by using three different plant leaf extracts, namely A. tricolor, A. blitum and A. paniculata, towards 3T3-L1 adipose cell lines. The morphology of MgO nanoparticles synthesized from A. tricolor leaf extract was modified to hexagonal forms via pH-induced transformations. The hexagonal-shaped MgO nanoparticles demonstrated less toxicity towards 3T3-L1 cell lines with an IC50 of 600 μl/ml dosage, whereas the spherical shaped nanoparticles exhibited size dependent cytotoxicity. The MgO nanoparticles were further subjected to a second stage cytotoxicity analysis using VERO cell lines as normal non-diabetic cells. The results showed that the phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles were less toxic to the non-diabetic cells even at a higher concentration of 1000 μl/ml. Bioanalysis using DNS-based colorimetric glucose assay, western blot, and fluorescence microscopy showed that the MgO nanoparticle possessed insulin resistance reversal abilities. The DNS glucose assay showed that the MgO nanoparticles reversed ~ 28% of insulin resistance, a result which was validated by the western blot analysis. Fluorescence microscopic studies also revealed that the nanoparticles possess binding ability towards the cell surface through electrostatic attraction and dissociate into ions. The dissociated oxygen species cause oxidative stress and disrupts the adipose cell membrane. The magnesium ions enter the cells through ion channels, activate relevant enzymes and reverse insulin resistance in the adipose cells. This study only represents a preliminary body of work in the evaluation of the prospects of phytosynthesized MgO nanoparticles for insulin resistance reversal in diabetes treatment. The cytotoxicity and insulin resistance reversal data show promising findings, hence more research effort is required for further validation. Mass spectroscopy and MALDI-TOF to analyze the disintegration of nanoparticles; flow cytometry to evaluate ROS production; and biochemical studies to examine the effect of nanoparticles in glycolysis pathway, mitochondrial function, and ATP production are highly recommended for comprehensive investigation of the insulin resistance reversal mechanism and antidiabetic effect of MgO nanoparticles.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- AMPK

5′ Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- DNS

Dinitro salicylic acid

- EDTA

Ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- GLUT4

Glucose transporter4

- MgO

Magnesium oxide

- MTT

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NCCS

National Cell Culture Society

- PARS

Poly (ADP-Ribose) synthetase

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- PVDF

Polyvinylidene difluoride

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- USA

United States of America

- w/v

Weight per volume

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Adochio R, Leitner JW, Hedlund R, Draznin B. Rescuing 3T3-L1 adipocytes from insulin resistance induced by stimulation of akt-mammalian target of rapamycin/p70 S6 Kinase (S6K1) pathway and serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1: effect of reduced expression of p85α subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and S6K1 kinase. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1165–1173. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Brashdi AS, Al-Ariymi H, Al Hashmi M, Khan SA. Evaluation of antioxidant potential, total phenolic content and phytochemical screening of aerial parts of a folkloric medicine, Haplophyllum tuberculatum (Forssk) A. Juss J Coastal Life Med. 2016;4:315–319. [Google Scholar]

- Alexis F, Pridgen E, Molnar LK, Farokhzad OC. Factors affecting the clearance and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2008;5:505–515. doi: 10.1021/mp800051m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amerasan D, Nataraj T, Murugan K, Panneerselvam C, Madhiyazhagan P, Nicoletti M, Benelli G. Myco-synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Metarhizium anisopliae against the rural malaria vector Anopheles culicifacies Giles (Diptera: Culicidae) J Pest Sci. 2016;89:249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Andra S, Balu SK, Jeevanandham J, Muthalagu M, Vidyavathy M, San Chan Y, Danquah MK. Phytosynthesized metal oxide nanoparticles for pharmaceutical applications. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2019;392:755–771. doi: 10.1007/s00210-019-01666-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranaz P, et al. Phenolic compounds inhibit 3T3-L1 adipogenesis depending on the stage of differentiation and their binding affinity to PPARγ. Molecules. 2019;24:1045. doi: 10.3390/molecules24061045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asemi Z, et al. Magnesium supplementation affects metabolic status and pregnancy outcomes in gestational diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:222–229. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.098616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai W-X, Wang C, Wang Y-J, Zheng W-J, Wang W, Wan X-C, Bao G-H. Novel acylated flavonol tetraglycoside with inhibitory effect on lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells from Lu’an GuaPian tea and quantification of flavonoid glycosides in six major processing types of tea. J Agricult Food Chem. 2017;65:2999–3005. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b00239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertinato J, Xiao CW, Ratnayake WN, Fernandez L, Lavergne C, Wood C, Swist E. Lower serum magnesium concentration is associated with diabetes, insulin resistance, and obesity in South Asian and white Canadian women but not men. Food Nutr Res. 2015;59:25974. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v59.25974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:941. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boo H-O, Park J-H, Lee M-S, Kwon S-J, Kim H-H. In Vitro Cytotoxicity against Human Cancer Cell and 3T3-L1 Cell Total Polyphenol Content and DPPH radical scavenging of codonopsis lanceolata according to the concentration of ethanol solvent. 한국자원식물학회지. 2018;31:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Borenfreund E, Puerner JA. Toxicity determined in vitro by morphological alterations and neutral red absorption. Toxicol Lett. 1985;24:119–124. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(85)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buse JB, et al. How do we define cure of diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2133. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona T, Shao S, Nixon PJ. Enhancing photosynthesis in plants: the light reactions. Essays Biochem. 2018;62:85–94. doi: 10.1042/EBC20170015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carluccio MA, et al. Olive oil and red wine antioxidant polyphenols inhibit endothelial activation: antiatherogenic properties of Mediterranean diet phytochemicals Arterioscler. Thromb, Vasc Biol. 2003;23:622–629. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000062884.69432.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael J, DeGraff WG, Gazdar AF, Minna JD, Mitchell JB. Evaluation of a tetrazolium-based semiautomated colorimetric assay: assessment of chemosensitivity testing. Cancer Res. 1987;47:936–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SM, Khoo KS, Sit NW. Interactions between plant extracts and cell viability indicators during cytotoxicity testing: implications for ethnopharmacological studies Trop J. Pharm Res. 2015;14:1991–1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chyau C-C, Chu C-C, Chen S-Y, Duh P-D. The inhibitory effects of djulis (chenopodium formosanum) and its bioactive compounds on adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Molecules. 2018;23:1780. doi: 10.3390/molecules23071780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman S, Wardzala L. Potential mechanism of insulin action on glucose transport in the isolated rat adipose cell. Apparent translocation of intracellular transport systems to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:4758–4762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di D-R, He Z-Z, Sun Z-Q, Liu J. A new nano-cryosurgical modality for tumor treatment using biodegradable MgO nanoparticles Nanomedicine. NBM. 2012;8:1233–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett D, Wirtz T. Co-registered in situ secondary electron and mass spectral imaging on the helium ion microscope demonstrated using lithium titanate and magnesium oxide nanoparticles. Anal Chem. 2017;89:8957–8965. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, Matsumura T, Edelstein D, Rossetti L, Zsengellér Z, Szabó C, Brownlee M. Inhibition of GAPDH activity by poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase activates three major pathways of hyperglycemic damage in endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1049–1057. doi: 10.1172/JCI18127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzoyem JP, Eloff JN. Anti-inflammatory, anticholinesterase and antioxidant activity of leaf extracts of twelve plants used traditionally to alleviate pain and inflammation in South Africa. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;160:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edidin M. Lipids on the frontier: a century of cell-membrane bilayers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:414. doi: 10.1038/nrm1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmendorf JS, Chen D, Pessin JE. Guanosine 5′-O-(3-Thiotriphosphate) (GTPγS) Stimulation of GLUT4 Translocation is Tyrosine Kinase-dependent. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13289–13296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eruygur N, Koçyiğit UM, Taslimi P, Ataş MEHMET, Tekin M, Gülçin İ. Screening the in vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial, anticholinesterase, antidiabetic activities of endemic Achillea cucullata (Asteraceae) ethanol extract. S Afr J Bot. 2019;120:141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Favaretto F, et al. GLUT4 defects in adipose tissue are early signs of metabolic alterations in Alms1GT/GT, a mouse model for obesity and insulin resistance. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e109540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiesleben S, Jäger A. Correlation between plant secondary metabolites and their antifungal mechanisms–a review. Med Aromat Plants. 2014;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M, Levin CE, Henika PR (2017) Addition of phytochemical-rich plant extracts mitigate the antimicrobial activity of essential oil/wine mixtures against Escherichia coli O157: H7 but not against Salmonella enterica. Food Control 73:562–565

- Ha BG, Moon D-S, Kim HJ, Shon YH. Magnesium and calcium-enriched deep-sea water promotes mitochondrial biogenesis by AMPK-activated signals pathway in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;83:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanan NA, Chiu HI, Ramachandran MR, Tung WH, Mohamad Zain NN, Yahaya N, Lim V. Cytotoxicity of plant-mediated synthesis of metallic nanoparticles: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1725. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houstis NE, Rosen ED, Lander ES. Reactive oxygen species have a causal role in multiple forms of insulin resistance. Nature. 2006;440:944–948. doi: 10.1038/nature04634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeevanandam J, Danquah MK, Debnath S, Debnath VS, Chan YS. Opportunities for nano-formulations in type 2 diabetes mellitus treatments. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2015;16:853–870. doi: 10.2174/1389201016666150727120618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeevanandam J, Chan YS, Danquah MK. Biosynthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles. ChemBioEng Rev. 2016;3:55–67. doi: 10.1002/cben.201500018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeevanandam J, Chan YS, Danquah MK. Biosynthesis and characterization of MgO nanoparticles from plant extracts via induced molecular nucleation. New J Chem. 2017;41:2800–2814. doi: 10.1039/C6NJ03176E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeevanandam J, Chan YS, Danquah MK. Calcination-dependent morphology transformation of Sol-Gel-Synthesized MgO Nanoparticles. Chem Select. 2017;2:10393–10404. [Google Scholar]

- Jeevanandam J, San Chan Y, Danquah MK. Biosynthesis and characterization of MgO nanoparticles from plant extracts via induced molecular nucleation. New J Chem. 2017;41:2800–2814. [Google Scholar]

- Jeevanandam J, Chan YS, Danquah MK. Effect of pH variations on morphological transformation of biosynthesized MgO nanoparticles. Part Sci Technol. 2019;38:573–586. [Google Scholar]

- Jeevanandam J, San Chan Y, Danquah MK, Law MC (2019b) Cytotoxicity analysis of morphologically different Sol-Gel-synthesized MgO nanoparticles and their in vitro insulin resistance reversal ability in adipose cells. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 1–26 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kabera JN, Semana E, Mussa AR, He X. Plant secondary metabolites: biosynthesis, classification, function and pharmacological properties. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2014;2:377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Kameshita I, Matsuda Z, Taniguchi T, Shizuta Y. Poly (ADP-Ribose) synthetase Separation and identification of three proteolytic fragments as the substrate-binding domain, the DNA-binding domain, and the automodification domain. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:4770–4776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaman DŞ, Manner S, Fallarero A, Rosenholm JM (2017) Current approaches for exploration of nanoparticles as antibacterial agents. In: Kumavath R (ed) Antibacterial agents 2017. IntechOpen Rijeka Croatia, pp 61–86

- Kim I-Y, Joachim E, Choi H, Kim K. Toxicity of silica nanoparticles depends on size, dose, and cell type nanomedicine. NBM. 2015;11:1407–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy K, Moon JY, Hyun HB, Cho SK, Kim S-J. Mechanistic investigation on the toxicity of MgO nanoparticles toward cancer cells. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:24610–24617. [Google Scholar]

- Kurstjens S, et al. Hypomagnesemia in type 2 diabetes is correlated with insulin resistance and changes in lipid metabolism in patients and mice. FASEB J. 2017;31(715):711–715. [Google Scholar]

- Lee PY, Yang CH, Kao MC, Su NY, Tsai PS, Huang CJ. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase beta, phosphoinositide 3-kinase delta, and phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma mediate the anti-inflammatory effects of magnesium sulfate. J Surg Res. 2015;197:390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung YH, et al. Mechanisms of antibacterial activity of MgO: non-ROS mediated toxicity of MgO nanoparticles towards Escherichia coli. Small. 2014;10:1171–1183. doi: 10.1002/smll.201302434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaudet L, Soriano FG, Szabó C Poly (ADP-Ribose) Synthetase as a Novel Therapeutic Target for Circulatory Shock. In: Vincent J-L (ed) Yearbook of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine 2001, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2001//2001. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 78–89

- Lihn AS, Pedersen SB, Richelsen B. Adiponectin: action, regulation and association to insulin sensitivity. Obes Rev. 2005;6:13–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Webster T (2016) Toxicity and biocompatibility properties of nanocomposites for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration. In: nanocomposites for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration. Elsevier, 95–122

- Luo X et al. (2017) PARP-1 controls the adipogenic transcriptional program by PARylating C/EBPβ and modulating its transcriptional activity Mol Cell 65:260–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Malik SK, Ahmed M, Khan F. Identification of novel anticancer terpenoids from prosopis juliflora (Sw) DC (Leguminosae) pods. Trop J Pharm Res. 2018;17:661–668. [Google Scholar]

- Martin OJ, Lee A, McGraw TE. GLUT4 distribution between the plasma membrane and the intracellular compartments is maintained by an insulin-modulated bipartite dynamic mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:484–490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505944200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy FC, Harford KA, Reynolds CM, Oliver E, Claessens M, Mills KH, Roche HM. Lack of interleukin-1 receptor I (IL-1RI) protects mice from high-fat diet–induced adipose tissue inflammation coincident with improved glucose homeostasis. Diabetes. 2011;60(6):1688–1698. doi: 10.2337/db10-1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meselhy KM, Shams MM, Sherif NH, El-sonbaty SM. Phytochemical study, potential cytotoxic and antioxidant activities of selected food byproducts (Pomegranate peel, Rice bran, Rice straw and Mulberry bark) Nat Prod Res. 2018;10(1080/14786419):1488708. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2018.1488708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirhosseini M, Afzali M. Investigation into the antibacterial behavior of suspensions of magnesium oxide nanoparticles in combination with nisin and heat against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus in milk. Food Control. 2016;68:208–215. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed SA, Al-Malki AL, Kumosani TA. Partial purification and characterization of five α-amylases from a wheat local variety (Balady) during germination. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2009;3:1740–1748. [Google Scholar]

- Monteilh-Zoller MK, Hermosura MC, Nadler MJ, Scharenberg AM, Penner R, Fleig A. TRPM7 provides an ion channel mechanism for cellular entry of trace metal ions. J Gen Physiol. 2003;121:49–60. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveen J, Baskaran V. Antidiabetic plant-derived nutraceuticals: a critical review. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57:1275–1299. doi: 10.1007/s00394-017-1552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh YS. Plant-derived compounds targeting pancreatic beta cells for the treatment of diabetes. J Evidence-Based Complementary Altern Med. 2015;2015:12. doi: 10.1155/2015/629863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakrashi S, et al. Vivo genotoxicity assessment of titanium dioxide nanoparticles by Allium cepa root tip assay at high exposure concentrations. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira L, Mehboob F, Stams AJ, Mota MM, Rijnaarts HH, Alves MM. Metallic nanoparticles: microbial synthesis and unique properties for biotechnological applications, bioavailability and biotransformation. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2015;35:114–128. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2013.819484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrak F, Baumeister H, Skinner TC, Brown A, Holt RIG. Depression and diabetes: treatment and health-care delivery. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:472–485. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polat R, Cakilcioglu U, Ulusan MD, Paksoy MY. Survey of wild food plants for human consumption in Elazığ (Turkey) Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2015;1:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Premanathan M, Karthikeyan K, Jeyasubramanian K, Manivannan G. Selective toxicity of ZnO nanoparticles toward Gram-positive bacteria and cancer cells by apoptosis through lipid peroxidation Nanomedicine. NBM. 2011;7:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmatullah M, et al. Antihyperglycemic and antinociceptive activity evaluation of methanolic extract of whole plant of Amaranthus Tricolor L. (Amaranthaceae) Afr J Tradit Complementary Altern Med. 2013;10:408–411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi C, Nicoletti I. Analysis of apoptosis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1458. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini RK, Moon SH, Gansukh E, Keum Y-S. An efficient one-step scheme for the purification of major xanthophyll carotenoids from lettuce, and assessment of their comparative anticancer potential. Food Chem. 2018;266:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.05.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangeetha RK, Baskaran V. Carotenoid composition and retinol equivalent in plants of nutritional and medicinal importance: Efficacy of β-carotene from Chenopodium album in retinol-deficient rats. Food Chem. 2010;119:1584–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Schröfel A, Kratošová G, Šafařík I, Šafaříková M, Raška I, Shor LM. Applications of biosynthesized metallic nanoparticles–A review. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:4023–4042. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehzad A, Qureshi M, Jabeen S, Ahmad R, Alabdalall AH, Aljafary MA, Al-Suhaimi E. Synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles using Rhazya stricta. PeerJ. 2018;6:e6086. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q, Li L, Jiang Y, Wang Q. Functional characterization of ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase from Andrographis paniculata with putative involvement in andrographolides biosynthesis. Biotechnol Lett. 2016;38:131–137. doi: 10.1007/s10529-015-1961-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng-Ji P. Ethnobotanical approaches of traditional medicine studies: some experiences from Asia. Pharm Biol. 2001;39:74–79. doi: 10.1076/phbi.39.s1.74.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simental-Mendía LE, Sahebkar A, Rodríguez-Morán M, Guerrero-Romero F. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the effects of magnesium supplementation on insulin sensitivity and glucose control. Pharmacol Res. 2016;111:272–282. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon H-U, Haj-Yehia A, Levi-Schaffer F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis. 2000;5:415–418. doi: 10.1023/a:1009616228304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R. Medicinal plants: a review. J Plant Sci. 2015;3:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. Glucose decorated gold nanoclusters: a membrane potential independent fluorescence probe for rapid identification of cancer cells expressing Glut receptors. Colloids Surf B. 2017;155:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Shedbalkar UU, Wadhwani SA, Chopade BA. Bacteriagenic silver nanoparticles: synthesis, mechanism, and applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:4579–4593. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6622-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Kim Y-J, Zhang D, Yang D-C. Biological synthesis of nanoparticles from plants and microorganisms. Trends Biotechnol. 2016;34:588–599. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivagnaname N, Kalyanasundaram M. Laboratory evaluation of methanolic extract of Atlantia monophylla (Family: Rutaceae) against immature stages of mosquitoes and non-target organisms. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99:115–118. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762004000100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ME, Morton DG (2010) 9 - THE ABSORPTIVE AND POST-ABSORPTIVE STATES. In: Smith ME, Morton DG (eds) The Digestive System (Second Edition). Churchill Livingstone 153–169. 10.1016/B978-0-7020-3367-4.00009-8

- Solowey E, Lichtenstein M, Sallon S, Paavilainen H, Solowey E, Lorberboum-Galski H. Evaluating medicinal plants for anticancer activity. Sci World J. 2014;2014:721402. doi: 10.1155/2014/721402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöckli J, Fazakerley DJ, James DE. GLUT4 exocytosis. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:4147–4159. doi: 10.1242/jcs.097063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarnakar NK, Thanki K, Jain S. Bicontinuous cubic liquid crystalline nanoparticles for oral delivery of Doxorubicin: implications on bioavailability, therapeutic efficacy, and cardiotoxicity. Pharm Res. 2014;31:1219–1238. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylow L, et al. Rac1 signaling is required for insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and is dysregulated in insulin-resistant murine and human skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2013;62:1865–1875. doi: 10.2337/db12-1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylow L, et al. Akt and Rac1 signaling are jointly required for insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and downregulated in insulin resistance. Cell Signalling. 2014;26:323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó C, Dawson VL. Role of poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase in inflammation and ischaemia–reperfusion. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:287–298. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01193-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan JBL, Lim YY. Critical analysis of current methods for assessing the in vitro antioxidant and antibacterial activity of plant extracts. Food Chem. 2015;172:814–822. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.09.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield P, Parry-Strong A, Walsh E, Weatherall M, Krebs JD. The effect of a cinnamon-, chromium- and magnesium-formulated honey on glycaemic control, weight loss and lipid parameters in type 2 diabetes: an open-label cross-over randomised controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55:1123–1131. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-0926-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widjajakusuma EC, et al. Phytochemical screening and preliminary clinical trials of the aqueous extract mixture of Andrographis paniculata (Burm. F.) Wall. ex Nees and Syzygium polyanthum (Wight.) Walp leaves in metformin treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Phytomedicine. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood M (2017) The book of herbal wisdom: using plants as medicines. North Atlantic Books Berkeley California United States, pp 1-535. ISBN-13: 978-1-55643-232-3

- Xiao K, et al. The effect of surface charge on in vivo biodistribution of PEG-oligocholic acid based micellar nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3435–3446. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Nagasaki Y, Kato Y, Sugiyama Y, Kataoka K. Long-circulating poly (ethylene glycol)–poly (d, l-lactide) block copolymer micelles with modulated surface charge. J Controlled Release. 2001;77:27–38. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00451-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi T et al. (2001) The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med 7:941 10.1038/90984https://www.nature.com/articles/nm0801_941#supplementary-information [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yameen B, Choi WI, Vilos C, Swami A, Shi J, Farokhzad OC. Insight into nanoparticle cellular uptake and intracellular targeting. J Controlled Release. 2014;190:485–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Wang J, Altura BT, Altura BM. Extracellular magnesium deficiency induces contraction of arterial muscle: role of PI3-kinases and MAPK signaling pathways. Pflugers Arch. 2000;439:240–247. doi: 10.1007/s004249900179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaccardi F, Webb DR, Yates T, Davies MJ. Pathophysiology of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 90-year perspective. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92:63–69. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahid K, Ahmed M, Khan F. Phytochemical screening, antioxidant activity, total phenolic and total flavonoid contents of seven local varieties of Rosa indica L. Nat Prod Res. 2018;32:1239–1243. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2017.1331228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.