Abstract

Background:

Measuring T1ρ in the knee menisci can potentially be used as noninvasive biomarkers in detecting early-stage osteoarthritis (OA).

Purpose:

To demonstrate the feasibility of biexponential T1ρ relaxation mapping of human knee menisci.

Study Type:

Prospective.

Population:

Eight healthy volunteers with no known inflammation, trauma, or pain in the knee and three symptomatic subjects with early knee OA.

Field Strength/Sequence:

Customized Turbo-FLASH sequence to acquire 3D-T1ρ-weighted images on a 3 T MRI scanner.

Assessment:

T1ρ relaxation values were assessed in 11 meniscal regions of interest (ROIs) using monoexponential and biexponential models.

Statistical Tests:

Nonparametric rank-sum tests, Kruskal–Wallis test, and coefficient of variation.

Results:

The mean monoexponential T1ρ relaxation in the lateral menisci were 28.05 ± 4.2 msec and 37.06 ± 10.64 msec for healthy subjects and early knee OA patients, respectively, while the short and long components were 8.07 ± 0.5 msec and 72.35 ± 3.2 msec for healthy subjects and 2.63 ± 2.99 msec and 55.27 ± 24.76 msec for early knee OA patients, respectively. The mean monoexponential T1ρ relaxation in the medial menisci were 34.30 ± 3.8 msec and 37.26 ± 11.38 msec for healthy and OA patients, respectively, while the short and long components were 7.76 ± 0.7 msec and 72.19± 4.2 msec for healthy subjects and 3.06 ± 3.24 msec and 55.27 ± 24.59 msec for OA patients, respectively. Statistically significant (P≤ 0.05) differences were observed in the monoexponential relaxation between some of the ROIs. The T1ρ,short was significantly lower (P = 0.02) in the patients than controls. The rmsCV% ranges were 1.51–16.6%, 3.59–14.3%, and 4.91–15.6% for T1ρ-mono, T1ρ-short, and T1ρ-long, respectively.

Data Conclusion:

Our results showed that in all ROIs, T1ρ relaxation times of outer zones (red zones) were less than inner zones (white zones). Monoexponential T1ρ was increased in medial, lateral, and body menisci of early OA while the biexponential numbers were decreased in early OA patients.

Level of Evidence:

2

Technical Efficacy Stage:

1

OSTEOARTHRITIS (OA) of the knee is a degenerative joint disease that affects about 10% of adults aged over 60 years.1,2 Knee menisci are vital for the normal function and long-term health of the knee joint. The menisci help to increase joint stability, shock absorption, load distribution on knee joint, and decreasing friction between articular surfaces; although the relationship between meniscal degeneration and OA is not clear it may be effective in the initiation of knee OA.3–7 The normal knee meniscus extracellular matrix is composed of 72% water, 22% collagen, and 0.8% proteoglycans and this composition may be altered due to OA.8,9 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has many advantages, including its ability to achieve high soft-tissue contrast among different tissues in the knee joint; however, clinical MRI protocols for knee imaging such as T1-weighted spoiled gradient echo (SPGR) sequences and fat-saturated T2 or proton density-weighted fast spin echo (FSE) are unable to quantitatively assess changes in tissue composition in the early stages of OA. Therefore, T1ρ relaxation measurement, which is sensitive to changes in the composition of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the meniscus, might be valuable for identifying individuals in need of early OA treatment and for detecting response to various therapies.10,11 Estimating T1ρ and T2 relaxation times (which are spin-lattice relaxation times in the rotating frame and spin-spin relaxation times) have been studied extensively as potential noninvasive biomarkers in detecting early-stage OA.12–16 T1ρ is sensitive to the slow-motional interactions between local macromolecular environments and bulk water17 and as a result to proteoglycan content in the tissue,18 while T2 is found to be sensitive to the collagen fibril orientation and anisotropy.19,20 Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis21 study validated the reliability (compiling 58 studies) and discriminative ability (compiling 26 studies) of T1ρ and T2 compositional mapping of knee cartilage, especially in mild knee OA as a motivation. T1ρ showed better discrimination for mild OA and OA compared to T2. The increase in water content and the loss of proteoglycans (PGs) in early-stage OA results in an elevation of the T1ρ relaxation times.14,22,23 A multicomponent model better represents the relaxation decay behavior than a monoexponential model because the monoexponential relaxation shows the weighted mean of relaxation in different water compartments in cartilage, while a multicomponent model distinguishes the relaxation time of different water compartments (eg, free water, water tightly bound to PG and collagen macromolecules, etc.).24

In this study we sought to demonstrate a method for measuring biexponential T1ρ relaxation times of knee menisci using MRI of healthy control subjects and early knee OA patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Group

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and complied with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guidelines. All the participants provided written informed consent prior to participating in this study. Eight healthy volunteers (women: n = 4, men: n = 4) who had no known inflammation, trauma, or prior knee surgeries with the mean age (±SD) of 30 ± 4 years (women: 26 ± 3 years, men: 30 ± 3 years), mean height of 169 ± 12 cm (women: 159 ± 6 cm, men: 177 ± 3 cm), mean weight of 52 ± 6 kg (women: 52 ± 6 kg, men: 74 ± 12 kg), and mean BMI (SD) of 20.9 ± 3.5 for women and 22.9 ± 2.8 for men and three symptomatic subjects (two females and a male) with early knee OA (KL-1, 2) with a mean age (±SD) of 51 ± 8 years, mean height and mean weight of 170 ± 9 and 79 ± 24, respectively, were enrolled in this study.

Ex Vivo Bovine Menisci Study

Fresh bovine meniscus specimens (n = 2, age = ~3 months old) were obtained from a slaughterhouse (Max Insel Cohen, Livingston, NJ) within 36 hours postmortem. The bovine meniscus specimens were equilibrated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 hour before the MRI study. 3D T1ρ-weighted images were obtained using a Cartesian Turbo-FLASH sequence that was customized to enable T1ρ imaging with varying spin-lock durations.24 The T1ρ preparation module consists of a 90° RF excitation pulse along the x-direction, followed by a spin-lock pulse along the y-direction and a −90° along the x-axis. To compensate for B0 inhomogeneity, an 180° refocusing pulse was applied in the middle of the module. Moreover, the phase of the spin-lock module was altered to compensate the B1 inhomogeneity effect.24 Series of T1ρ-weighted images were acquired at 15 different spin-lock lengths (TSLs), including 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 25, 35, 40, 45, 55, and 65 msec. MRI acquisition parameters were as follows: repetition time (TR) = 1500 msec, echo time (TE) = 4 msec, bandwidth = 515 Hz/pixel, matrix size = 256 × 128 × 64; slice thickness = 2 mm, flip angle (FA) = 8°, field of view (FOV) = 120 × 120 mm, frequency of spin-lock = 500 Hz. The frequency of spin-lock was set to 500 Hz as a good trade-off between observing the biexponential behavior and reducing the magic angle effect.24 The experiment was repeated with different acceleration factors (AFs) = 1–4 to examine the effect of reduced signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) due to parallel imaging on the estimated relaxation times. The maps were also estimated for 6 (5, 15, 25, 35, 45, 55) and 10 TSLs (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, 25, 35, 45, 55) to compare the effect of number of time points on estimation error.

In Vivo Knee Menisci Study

All subjects arrived at the MRI center 30 minutes prior to data acquisition and the knee joint of the leg was scanned with a 3 T clinical MRI scanner (Magnetom Prisma, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) in the feet-first supine position with a 15-channel TX/RX knee coil (Quality Electrodynamics, Cleveland, OH). Sagittal 3D T1ρ-weighted scans of the knee were obtained at 10 different spin-lock durations (TSLs) including TSL: 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, 25, 35, 45, and 55 msec. Sagittal 3D T1ρ-weighted scans of the knee were obtained at 10 different spin-lock durations (TSLs) including TSL: 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, 25, 35, 45, and 55 msec, with the same imaging parameters as the ex vivo study. A generalized auto-calibrating partially parallel acquisition (GRAPPA) acceleration factor of 3 was used to achieve a total scan time of 15 minutes for in vivo study.

Multicomponent T1ρ Relaxation Analysis

The mono- and biexponential T1ρ relaxations were reconstructed pixel-by-pixel across the regions of interest (ROIs) in MatLab (v. R2016a; MathWorks, Natick, MA). The monoexponential relaxation time, T1ρmono, was calculated by fitting the monoexponential model to the data:

| (1) |

Where y(tsl) is the pixel signal intensity in the scan acquired at the spin-lock duration, TSL. y0 is the constant term that was set to the noise standard deviation.

Similarly, the biexponential relaxation components were estimated by fitting the biexponential model to the same data set using a nonlinear approach:

| (2) |

Where T1ρlong and T1ρshort are the long and short relaxation time components, respectively. The relative fractions of the long (yl) and the short (ys) components are reported as and , respectively.

Afterward, the pixels satisfying the below condition were included in the mean estimation25:

| (3) |

Meniscus Segmentation

T1ρ of the menisci of all 11 subjects (eight healthy and three knee OA patients) in the study group were estimated in nine different ROIs including meniscus body (MB), posterior-medial menisci (PM), anterior-medial menisci (AM), posterior-lateral menisci (PL), anterior-lateral menisci (AL), and the segmented menisci regions were then divided into two subcompartments that are red zone (RZ) and white zone (WZ) (Fig. 1). Meniscus segmentation was performed using the shortest TSL = 2 (therefore, with highest SNR) of T1ρ-weighted images. First, the ROI masks were drawn manually using ITK-SNAP (v. 3.6.0)26 then the segmentation masks transferred to MatLab for T1ρ measurements.

FIGURE 1:

Representative sagittal T1ρ-weighted (TSL = 2 msec) illustrating the ROIs of meniscus subregions in lateral, medial, and body menisci.

Mont Carlo Simulation

Monte Carlo simulations27 were performed to determine the effects of different parameters such as number of TSLs and SNR on estimating four parameters in a biexponential model (two relaxation times and the corresponding fractions). A biexponential decay curve with known T1ρ component fractions and time constants were generated using the array of TSL times. A random Rician noise was then added to the signal and the relaxation components were estimated by fitting the biexponential model Eq. [2] to the noisy signals. The process was repeated for N = 1000 independent noise trails, and the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) was calculated as:

| (4) |

Where Ta and Te are the actual and estimated relaxation values, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

We performed a Kruskal–Wallis test to compare the relaxation components between different ROIs and zones and differences were deemed to be significant at P < 0.05. The histogram of calculated pixel T1ρ mono, T1ρ long, and T1ρ short was characterized by calculating the mean, standard deviation, median, mode, skewness, and kurtosis of the distribution. The mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) used to find differences between the estimation using 15 TSLs (as reference) with the estimation using 10 and 6 TSLs. All statistical testing was performed with Minitab (Minitab 18 Statistical Software, Minitab) and MatLab.

As the measure of repeatability of T1ρ relaxation components (mono-short-long) in different ROIs, the experiment was repeated on two volunteers on two different days with a 2-week gap. For each subject, the mean and SD were calculated across the two sessions, and the coefficient of variation (CV), representing the relative magnitude (%) was calculated as CV = SD/mean. To depict the repeatability, root-mean-square coefficients of variation (rmsCV) for each ROI was calculated as28:

| (5) |

where i is the subject number and N is the total number of subjects (N = 2) in the repeatability study.

Results

T1ρ-relaxation maps (mono-short-long) of a bovine meniscus from representative slices are shown in Fig. 2a–c, respectively. Considering the estimated T1ρ values from fully sampled data as a reference, Fig. 2d shows the estimation error for different GRAPPA acceleration factors (AF = 2–4). Using an AF of 3 will decrease the total acquisition time from 31 to 16 minutes, while the estimated relaxations have less than 6% difference from the estimated values derived from fully sampled data. Therefore, AF = 3 was selected for performing the in vivo experiments. The differences between the T1ρ values using 15 TSLs as a reference with the estimation using 10 and 6 TSLs are shown in Fig. 2e. The results show less than a 5% bias between the relaxation values estimated using 10 TSL points, which is in agreement with our Monte Carlo simulation (Fig. 3b). Therefore, 10 TSLs points were used in the in vivo studies.

FIGURE 2:

Ex vivo study on the bovine menisci. (a) Mono, (b) short, and (c) long component spatial T1ρ maps. (d) The estimated parameters from scans acquired with an AF = 3 show less than a 6% difference from the fully sampled scans. (e) The estimated relaxations using 10 TSLs showed less than 6% difference from the estimated relaxations using 15 TSLs points.

FIGURE 3:

Monte Carlo simulations. Effect of different parameters on biexponential model. (a) The estimation mean-absolute percentage error (MAPE) decreases by increasing the number of TSLs. (b) Higher SNR leads to less estimation error. (c) The estimation is more accurate for shorter short component (T1ρs). (d) The estimation is more accurate for larger long component (T1ρl). (e,f) The component with larger fraction (short component, As, in (e) and long component, Al in (f)) has better estimation than the component with a shorter fraction.

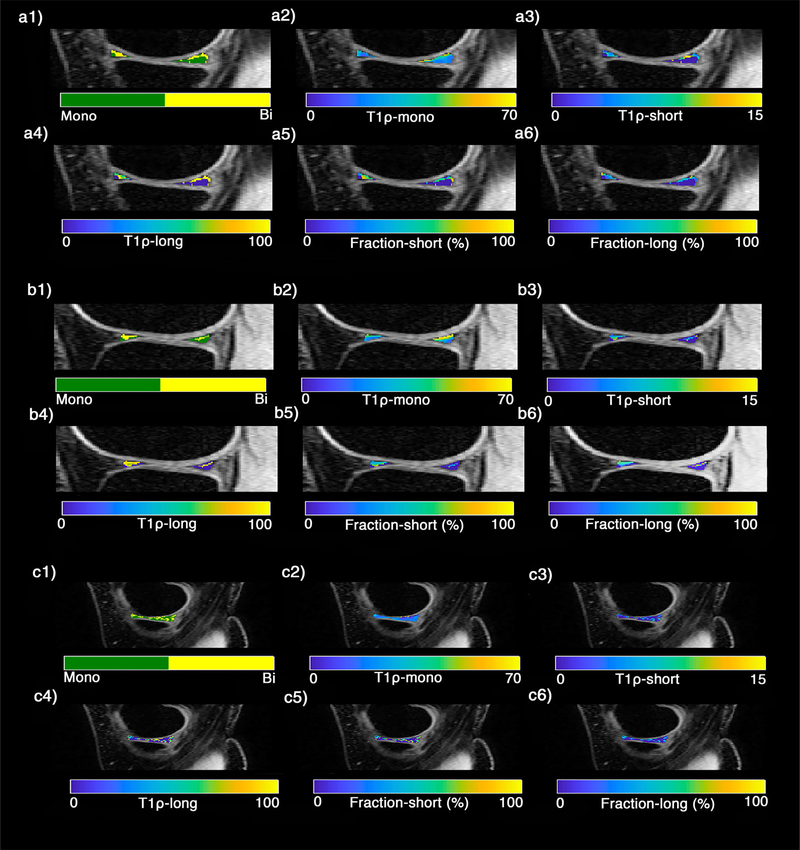

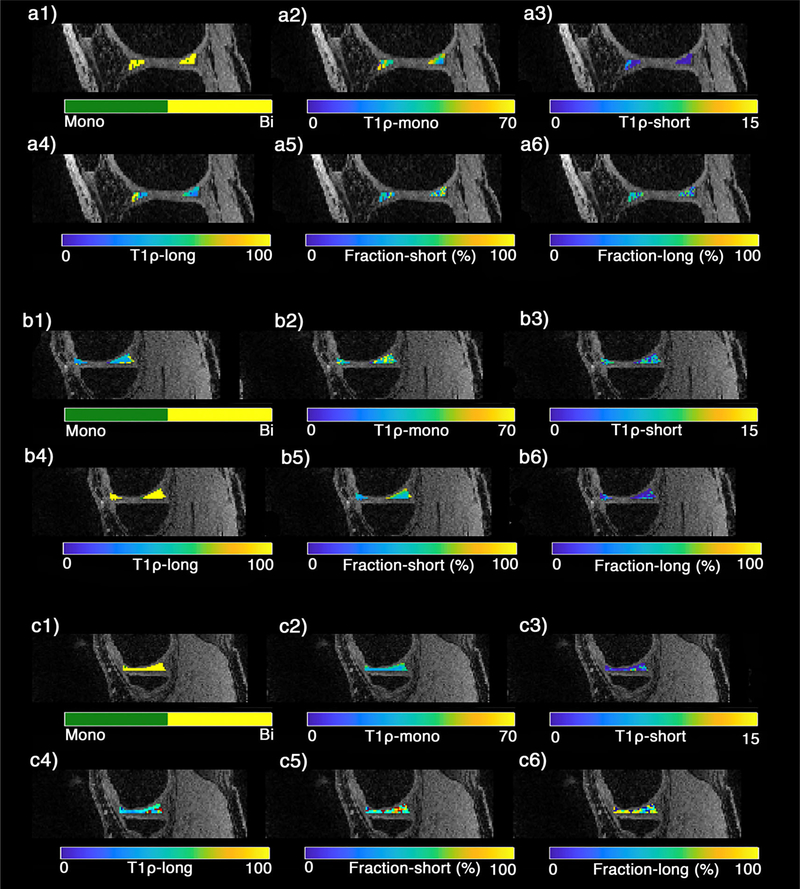

The representative examples of the T1ρ relaxation maps in the sagittal plane for a healthy subject and an early knee OA patient are shown in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. The binary maps (Figs. 3–4, a1–c1) show the pixels that were included in the biexponential map by satisfying Eq. 3. The summary of descriptive statistics in different ROIs for healthy subjects and early OA patients are shown in Table 1. The T1ρ short and T1ρ long ranges were 5.49–10.60 msec and 58.85–78.44 msec in healthy subjects and 2.00–8.08 msec and 46.29–73.04 msec in OA patients, respectively. The long component fractions were 44.66% and 40.10% for healthy subjects and early knee OA patients, respectively, while the short component fractions were 53.06% and 59.90% for healthy subjects and early knee OA patients, respectively. The average SNR of the experiments was 32.1 ± 9.32. Based on Monte Carlo simulation results (Fig. 3a), there is less than 15% error in estimating the biexponential components for SNR between 25 and 35.

FIGURE 4:

A representative example of T1ρ relaxation maps of knee menisci in healthy subject in (a1–a6) lateral, (b1–b6) medial, (c1–c6) body menisci. (a1–c1) The binary maps show the pixels that were included in the biexponential map (yellow) by satisfying the Eq. 3 condition.

FIGURE 5:

A representative example of T1ρ relaxation maps of knee menisci in early OA patient in (a1–a6) lateral, (b1–b6) medial, (c1–c6) body menisci. (a1–c1) The binary maps show the pixels that were included in the biexponential map (yellow) by satisfying the Eq. 3 condition

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Mono- and Biexponential Relaxation Times (Mean ± SD and 95% Confidence Intervals) in Nine Regions of Interest for Eight Healthy Controls and Three Early OA Patients

| ROI | T1ρmono (msec) |

T1ρshort (msec) |

T1ρlong (msec) |

Yshort (%) |

Ylong (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Control | |||||

| PLWZ | 39.29 ± 5.1 | 10.60 ± 0.7 | 78.44 ± 3.8 | 44.47 ± 8.3 | 51.37 ± 8.3 |

| PLRZ | 28.42 ± 6.19 | 9.52 ± 1.1 | 77.86 ± 8.7 | 57.76 ± 5.4 | 42.24 ± 15.3 |

| ALWZ | 22.20 ± 4.3 | 6.69 ± 0.6 | 75.16 ± 4.2 | 66.97 ± 7.0 | 33.03 ± 7.0 |

| ALRZ | 20.80 ± 5.8 | 5.49 ± 0.4 | 63.02 ± 1.8 | 62.24 ± 6.0 | 29.43 ± 6.0 |

| PMWZ | 42.19 ± 6.8 | 9.65 ± 1.4 | 73.64 ± 8.5 | 39.05 ± 6.2 | 56.78 ± 6.2 |

| PMRZ | 33.96 ± 5.3 | 8.08 ± 0.7 | 68.90 ± 4.2 | 46.92 ± 11.7 | 44.75 ± 11.7 |

| AMWZ | 31.00 ± 6.0 | 6.99 ± 0.7 | 75.87 ± 3.5 | 56.78 ± 7.6 | 43.22 ± 7.6 |

| AMRZ | 30.19 ± 6.1 | 7.10 ± 0.8 | 77.80 ± 4.9 | 60.84 ± 11.1 | 39.16 ± 11.0 |

| MB | 21.34 ± 2.52 | 6.39 ± 0.6 | 58.85 ± 1.82 | 36.0 ± 7.6 | 64.0 ± 7.6 |

| Patients | |||||

| PLWZ | 37.25 ± 9.50 | 2.00 ± 2.72 | 47.29. ± 19.57 | 55.13 ± 23.53 | 44.87 ± 23.53 |

| PLRZ | 33.25 ± 9.20 | 2.26 ± 2.73 | 46.29 ± 21.48 | 58.88 ± 23.05 | 41.11 ± 23.05 |

| ALWZ | 37.21 ± 8.42 | 2.54 ± 3.14 | 52.69 ± 24.84 | 57.01 ± 21.95 | 42.99 ± 21.95 |

| ALRZ | 42.57 ± 11.61 | 3.33 ± 3.13 | 73.04 ± 22.93 | 58.89 ± 20.50 | 41.11 ± 20.50 |

| PMWZ | 37.91 ± 11.34 | 3.06 ± 3.11 | 61.82 ± 23.84 | 61.86 ± 23.80 | 38.14 ± 23.80 |

| PMRZ | 35.63 ± 9.72 | 8.08 ± 3.23 | 68.90 ± 26.56 | 46.92 ± 24.39 | 44.75 ± 24.39 |

| AMWZ | 38.58 ± 11.01 | 3.77 ± 3.79 | 64.83 ± 23.29 | 61.87 ± 21.76 | 38.13 ± 21.76 |

| AMRZ | 37.02 ± 8.46 | 2.62 ± 3.29 | 50.23 ± 20.98 | 57.10 ± 25.30 | 42.90 ± 25.30 |

| MB | 34.70 ± 7.19 | 3.23 ± 3.38 | 59.05 ± 24.92 | 62.14 ± 23.06 | 37.86 ± 23.06 |

SD: Standard Deviation; PLWZ: Posterior-Lateral White Zone; PLRZ: Posterior-Lateral Red Zone; ALWZ: Anterior- Lateral White Zone; ALRZ: Anterior-Lateral Red Zone;; PMWZ: Posterior-Medial White Zone; PMRZ: Posterior-Medial Red Zone; AMWZ: Anterior-Medial White Zone; AMRZ: Anterior-Medial Red Zone;; MB: Meniscus Body.

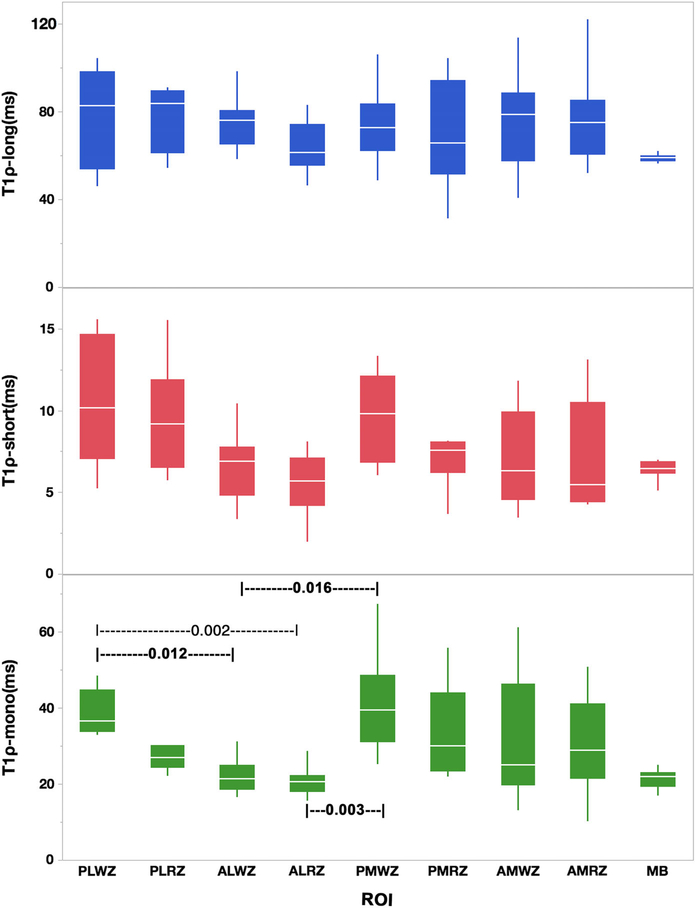

Figure 6 shows the comparison of the T1ρ relaxation components in different ROIs. The pairwise statistically significant ROIs are shown with the black dashed line and the rank sum test P-values.

FIGURE 6:

The boxplot shows the T1ρ relaxation times component between nine different ROIs. The line in the middle of each box is the median and the bars extending from the boxes are the minimum and maximum values. The dashed line with numbers show the pairwise rank sum test between two ROIs (PLWZ: Posterior-Lateral White Zone; PLRZ: Posterior-Lateral Red Zone; ALWZ: Anterior-Lateral White Zone; ALRZ: Anterior-Lateral Red Zone; TLM: Total Lateral Menisci; PMWZ: Posterior-Medial White Zone; PMRZ: Posterior-Medial Red Zone; AMWZ: Anterior-Medial White Zone; AMRZ: Anterior-Medial Red Zone; TMM: Total Medial Menisci; MB: Meniscus Body).

The monoexponential T1ρ relaxation in PLWZ was significantly different from that of ALWZ and ALRZ (P = 0.012 and P = 0.002, respectively). Moreover, PMWZ demonstrated significantly higher monoexponential T1ρ relaxation values than that of ALWZ (P = 0.016) and ALRZ (P = 0.003).

Figure 7 shows the comparison of the T1ρ relaxation components in different ROIs between females and males. The Mann–Whitney U-test showed no significant difference (P > 0.05) between females and males for each component per ROI.

FIGURE 7:

The boxplot shows the T1ρ relaxation times component (mono, short and long) between different genders.

The comparison between control and patient groups showed a significantly higher mono T1ρ relaxation in anterior lateral red (P = 0.04) and white (P = 0.02) zones as well as the meniscal body (P = 0.02) in the patients. However, the global difference was not significant (P = 0.3). No difference was observed in the long relaxation time components (P = 0.7). The short component was significantly lower for patients in posterior lateral red (P = 0.02) and white (P = 0.02), posterior medial red (P = 0.04) and white (P = 0.02), anterior medial white (P = 0.02) and body (P = 0.02) zones. The global short relaxation component was also significantly lower in patients (P = 0.02) than in the control group.

Fig. 8a–c shows the mono- and biexponential fit and their corresponding residuals in representative slices of the lateral, medial, and body of the meniscus, respectively.

FIGURE 8:

Monoexponential vs. biexponential fitting models. T1ρ decay on a logarithmic scale and the fitted residuals of representative pixels in lateral (a), medial (b), and body (c) of knee meniscus. The deviation of the data from a straight line shows the existence of more than one exponential term.

Table 2 shows all repeatability results (CV%, rmsCV%), together with mean T1ρ values, for each component and for each of the analyzed ROIs. The rmsCV% range was 1.51–16.6% for T1ρ-mono and 3.59–14.3% and 4.91–15.6% for T1ρ-short and T1ρ long, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Intersubject Repeatability of T1ρ Mono, Long, and Short Components

| ROI | T1ρ,mono |

T1ρ,long |

T1ρ,short |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (msec) | CV | rmsCV% | Mean (msec) | CV% | rmsCV% | Mean (msec) | CV% | rmsCV% | |

| PLWZ | 36.42 | 0.035 | 4.85 | 60.67 | 0.073 | 9.63 | 8.58 | 0.048 | 4.91 |

| PLRZ | 24.22 | 0.068 | 4.39 | 69.62 | 0.105 | 11.0 | 8.08 | 0.066 | 6.65 |

| ALWZ | 25.09 | 0.001 | 13.8 | 62.47 | 0.026 | 3.59 | 8.18 | 0.149 | 14.9 |

| ALRZ | 31.75 | 0.089 | 8.81 | 67.17 | 0.059 | 5.98 | 9.00 | 0.050 | 5.01 |

| PMWZ | 36.06 | 0.014 | 1.51 | 68.63 | 0.112 | 11.4 | 11.245 | 0.109 | 10.9 |

| PMRZ | 22.22 | 0.042 | 4.25 | 60.69 | 0.060 | 6.08 | 8.77 | 0.111 | 11.1 |

| AMWZ | 20.64 | 0.154 | 16.6 | 70.66 | 0.136 | 14.3 | 8.05 | 0.061 | 6.12 |

| AMRZ | 22.54 | 0.079 | 8.09 | 74.13 | 0.090 | 11.1 | 6.72 | 0.156 | 15.6 |

| MB | 23.45 | 0.091 | 12.1 | 52.92 | 0.068 | 7.10 | 6.1 | 0.123 | 12.3 |

SD: Standard Deviation; PLWZ: Posterior-Lateral White Zone; PLRZ: Posterior-Lateral Red Zone; ALWZ: Anterior- Lateral White Zone; ALRZ: Anterior-Lateral Red Zone; PMWZ: Posterior-Medial White Zone; PMRZ: Posterior-Medial Red Zone; AMWZ: Anterior-Medial White Zone; AMRZ: Anterior-Medial Red Zone; MB: Meniscus Body; CV = Coefficient of Variation; rmsCV = Root-Mean-Square Coefficient of Variation.

Discussion

In this article we present a 3D-MRI technique for bicomponent T1ρ analysis of subregional, compartmental, and whole knee menisci in nine different ROIs in vivo. The most significant finding of the present study is that biexponential fitting better represents T1ρ relaxation time values measured in each ROI. Although prior studies have shown that monoexponential fitting can obtain T1ρ and T2 values that correlate strongly with water content in OA menisci, these values do not strongly correlate with proteoglycan content and may have limited ability to detect compositional variation in degenerated menisci.29,30

We reported the biexponential T1ρ analysis of knee menisci in vivo in different vertical zones. The model provides both short (which is sensitive to early biochemical changes) and long relaxation times with their corresponding fractions. The short component is related to water tightly bound to macromolecules, while the long component is related to water molecules loosely bound to macromolecules.31 Hence, we expect that the biexponential T1ρ provides higher specificity to macromolecular loss in cartilage compared with a monoexponential model. Most of the published literature on T1ρ relaxation times have been performed utilizing monoexponential fitting; however, the T1ρ relaxation range in our study was comparable to that of other studies,12–14,16,22,32,33 but there were some differences. These differences may be due to two main reasons. First, the slice thickness in this study (2 mm) was smaller compared to other studies, which were 3 mm or 4 mm; this leads to a decrease in partial volume effects (PVEs). Second, we acquired 10 spin-lock times (TSLs) compared with other studies that used 4 to 6 TSLs.

There have been few studies16,34,35 describing T1ρ relaxation times in different vertical zones of knee menisci. Takao et al35 reported that results of T1ρ relaxation times of the white zone were significantly higher than those of the red zone in all segments, which is in agreement with our results. T1ρ relaxation times reported by Subburaj et al34 were lower than those in our current work; this difference is probably caused by the difference in the number of TSLs and slice thickness, as mentioned above. Other studies have shown similar zonal variation. For instance, Calixto et al16 investigated T1ρ relaxation times for both healthy subjects and patients with knee OA in unloaded and loading conditions. In healthy subjects at the unloaded situation, inner lateral and medial posterior horn values were higher than in the outer zone, suggesting underlying differences in macromolecular organization in these subregions of the meniscus. Similarly, Nebelung et al36 investigated an ex vivo quantitative multiparametric MRI mapping study of degenerated human menisci that showed T1, T1ρ, T2, and UTE-T2* relaxation times are functionally related to histological meniscus degeneration.

The mean of T1ρ relaxation times in nine different ROIs for early knee OA patients in our study (35.20 msec) was higher than the mean of T1ρ relaxation times in healthy subjects (29.72 msec). Also, the estimated range of T1ρ relaxation times for patients in our study are in agreement with previous studies.37,38

The mean of T1ρ-short in healthy subjects (7.83 msec) was higher than T1ρ-short in early knee OA patients (3.00 msec) and the mean of T1ρ-long in healthy subjects (72.19 msec) was higher than the mean of T1ρ-long in healthy subjects (57.01). In addition, the short component fractions in early knee OA patients (59.90) was higher than short component fractions in healthy subjects (53.06), while the long component fractions in early knee OA patients (40.10) was less than long component fractions in healthy subjects (44.66).

The investigated reproducibility of T1ρ relaxation times (rmsCV) numbers in prior studies35,39 are in good agreement with our experiments, where the rmsCV of 4.91–15.6% was measured for monoexponential T1ρ.

This study had several limitations. First and foremost, there was a relatively small number of asymptomatic healthy and OA patients recruited. Second, there could be measurement bias resulting from the manually drawn ROIs in different subjects. Third, although we confirmed our experimental condition (4TS < Tl) for biexponential mapping, there might be some bias. We chose this condition based on the suggestion in the Juras et al study.25 Finally, there was a difference between healthy and early OA patients’ mean ages (healthy: 30, patient: 51).

In conclusion, a 3D Turbo-FLASH-based sequence was implemented for simultaneous mono- and biocomponent T1ρ relaxation mapping analysis of the human knee meniscus. Our preliminary results show that in all ROIs, T1ρ relaxation times of outer zones (red zones) less than inner zones (white zones) and T1ρ mapping can potentially be used to increase the specificity of early OA diagnosis by estimating the relaxation time of different water compartments and their fractions.

Although there is no ground truth for validation of a biexponential model in vivo, we recently used synthetic phantoms with known relaxation times and fractions and validated the biexponential model with different noise levels.40

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health (NIH); Contract grant numbers: R01-AR060238, R01-AR067156, and R01-AR068966; performed under the rubric of the Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research (CAI2R), an NIBIB Biomedical Technology Resource Center (NIH P41-EB017183).

References

- 1.Krasnokutsky S, Belitskaya-Lévy I, Bencardino J, et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging evidence of synovial proliferation is associated with radiographic severity of knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63:2983–2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott D, Kowalczyk A. Osteoarthritis of the knee. BMJ Clin Evid 2007;2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Englund M, Niu J, Guermazi A, et al. Effect of meniscal damage on the development of frequent knee pain, aching, or stiffness. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:4048–4054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosher TJ, Liu Y, Yang QX, et al. Age dependency of cartilage magnetic resonance imaging T2 relaxation times in asymptomatic women. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:2820–2828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox AJS, Bedi A, Rodeo SA. The basic science of human knee menisci: Structure, composition, and function. Sports Health 2012;4:340–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lange AK, Fiatarone Singh MA, Smith RM, et al. Degenerative meniscustears and mobility impairment in women with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2007;15:701–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, Roos EM. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: Osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med 2007;35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J-S, Hosseini A, Cancre L, Ryan N, Rubash HE, Li G. Kinematic characteristics of the tibiofemoral joint during a step-up activity. Gait Posture 2013;38:712–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herwig J, Egner E, Buddecke E. Chemical changes of human knee joint menisci in various stages of degeneration. Ann Rheum Dis 1984;43: 635–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stahl R, Luke A, Li X, et al. T1rho, T2 and focal knee cartilage abnormalities in physically active and sedentary healthy subjects versus early OA patients—A 3.0-Tesla MRI study. Eur Radiol 2009;19:132–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baum T, Joseph GB, Karampinos DC, Jungmann PM, Link TM, Bauer JS. Cartilage and meniscal T2 relaxation time as non-invasive biomarker for knee osteoarthritis and cartilage repair procedures. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:1474–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rauscher I, Stahl R, Cheng J, et al. Meniscal measurements of T1ρ and T2 at MR imaging in healthy subjects and patients with osteoarthritis. Radiology 2008;249:591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zarins ZA, Bolbos RI, Pialat JB, et al. Cartilage and meniscus assessment using T1rho and T2 measurements in healthy subjects and patients with osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:1408–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Chang G, Xu J, et al. T1rho MRI of menisci and cartilage inpatients with osteoarthritis at 3T. Eur J Radiol 2012;81:2329–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Son M, Goodman SB, Chen W, Hargreaves BA, Gold GE, Levenston ME. Regional variation in T1rho; and T2 times in osteoarthritic human menisci: Correlation with mechanical properties and matrix composition. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:796–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calixto NE, Kumar D, Subburaj K, et al. Zonal differences in meniscus MR relaxation times in response to in vivo static loading in knee osteoarthritis. J Orthopaed Res 2016;34:249–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regatte RR, Akella SV, Borthakur A, Kneeland JB, Reddy R. Proteoglycan depletion-induced changes in transverse relaxation maps of cartilage: Comparison of T2 and T1ρ. Acad Radiol 2002;9:1388–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akella SV, Regatte RR, Borthakur A, Kneeland JB, Leigh JS, Reddy R. T1ρ MR imaging of the human wrist in vivo. Acad Radiol 2003;10:614–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray ML, Burstein D, Xia Y. Biochemical (and functional) imaging of articular cartilage Seminars in musculoskeletal radiology. Volume 5 New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2001. p 329–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng S, Xia Y. Multi-components of T 2 relaxation in ex vivo cartilage and tendon. J Magn Reson 2009;198:188–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKay JW, Low SBL, Smith TO, Toms AP, McCaskie AW, Gilbert FJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the reliability and discriminative validity of cartilage compositional MRI in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2018;26:1140–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Benjamin Ma C, Link TM, et al. In vivo T1ρ and T2 mapping of articular cartilage in osteoarthritis of the knee using 3 T MRI. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2007;15:789–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L, Regatte RR. T1ρ MRI of human musculoskeletal system. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015;41:586–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharafi A, Xia D, Chang G, Regatte RR. Biexponential T1ρ relaxation mapping of human knee cartilage in vivo at 3 T. NMR Biomed 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juras V, Apprich S, Zbýò Š, et al. Quantitative MRI analysis of menisci using biexponential T2* fitting with a variable echo time sequence. Magn Reson Med 2014;71:1015–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, et al. User-guided 3D active contoursegmentation of anatomical structures: Significantly improved efficiency and reliability. NeuroImage 2006;31:1116–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubinstein RY, Kroese DP. Simulation and the Monte Carlo method. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glüer C-C, Blake G, Lu Y, Blunt BA, Jergas M, Genant HK. Accurate assessment of precision errors: How to measure the reproducibility of bone densitometry techniques. Osteoporosis International 1995;5: 262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kajabi AW, Casula V, Nissi MJ, et al. Assessment of meniscus with adiabatic T1ρ and T2ρ relaxation time in asymptomatic subjects and patients with mild osteoarthritis: A feasibility study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2018; 26:580–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirsch S, Kreinest M, Reisig G, Schwarz MLR, Ströbel P, Schad LR. In vitro mapping of 1H ultrashort T2* and T2 of porcine menisci. NMR Biomed 2013;26:1167–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reiter DA, Lin P-C, Fishbein KW, Spencer RG. Multicomponent T2 relaxation analysis in cartilage. Magn Reson Med 2009;61:803–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stehling C, Luke A, Stahl R, et al. Meniscal T1rho and T2 measured with3.0T MRI increases directly after running a marathon. Skeletal Radiol 2011;40:725–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma YJ, Carl M, Searleman A, Lu X, Chang EY, Du J. 3D adiabatic T1ρ prepared ultrashort echo time cones sequence for whole knee imaging. Magn Reson Med 2018;80:1429–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Subburaj K, Souza RB, Wyman BT, et al. Changes in MR relaxation timesof the meniscus with acute loading: An in vivo pilot study in knee osteoarthritis. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015;41:536–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takao S, Nguyen TB, Yu HJ, et al. T1rho and T2 relaxation times of thenormal adult knee meniscus at 3T: Analysis of zonal differences. BMC Musculoskel Disord 2017;18:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nebelung S, Tingart M, Pufe T, Kuhl C, Jahr H, Truhn D. Ex vivo quantitative multiparametric MRI mapping of human meniscus degeneration. Skeletal Radiol 2016;45:1649–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ligong W, Gregory C, Jenny B, et al. T1rho MRI of menisci in patients with osteoarthritis at 3 Tesla: A preliminary study. J Magn Reson Imaging 2014;40:588–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Souza RB, Feeley BT, Zarins ZA, Link TM, Li X, Majumdar S. T1rho MRI relaxation in knee OA subjects with varying sizes of cartilage lesions. Knee 2013;20:113–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X, Wyatt C, Rivoire J, et al. Simultaneous acquisition of T1ρ and T2 quantification in knee cartilage: Repeatability and diurnal variation. J Magn Reson Imaging 2014;39:1287–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zibetti MVW, Sharafi A, Otazo R, Regatte RR. Compressed sensing acceleration of biexponential 3D-T1ρ relaxation mapping of knee cartilage. Magn Reson Med 2019;81:863–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]