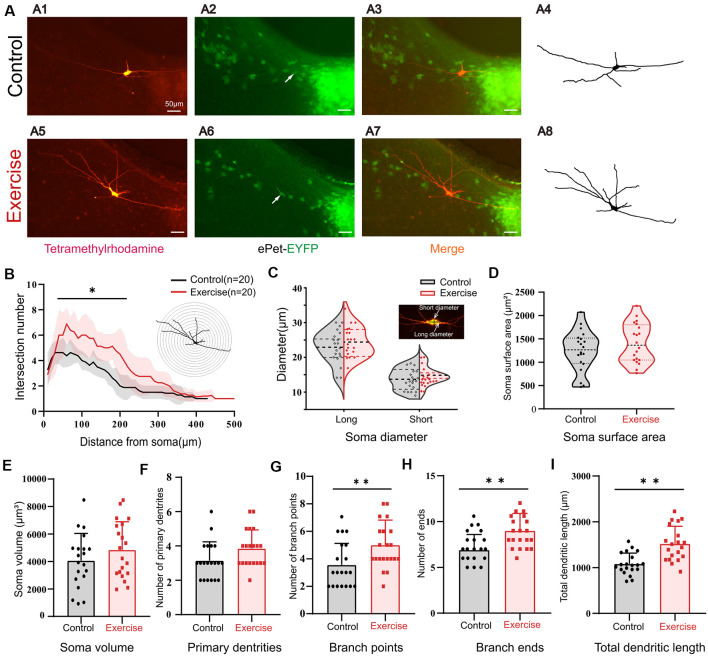

Figure 7.

Treadmill exercise facilitated dendritic plasticity. (A) Example of exercise training increased the number of dendrites; (A1) fluorescence image of staining of tetramethylrhodamine in control group; (A2) fluorescence image of EYFP-positive neurons; (A3) merged image of (A1) and (A2); (A4) neuronal morphology diagram reconstructed with Sholl analysis in (A1); (A5) fluorescence image of staining of tetramethylrhodamine in exercise group; (A6) fluorescence image of EYFP-positive neurons in the exercise group; (A7) merged image of (A5,A6); (A8) neuronal morphology reconstructed with Sholl analysis in (A5). (B) The illustration at the top right is an example of Sholl analysis, in which a series of concentric circles around the soma were created and then counted times the dendrite intersecting the circle (intersections) as well as the length of each dendritic arbor segment within each radius. The number of intersections in the range of 50–200 μm from the soma increased significantly in the exercise group; (p < 0.05). (C) Most 5-HT cell bodies were fusiform, so we measured the long and short diameters of the cell bodies as shown in the illustration at the top right. Exercise training had little effect on neuron diameters (short diameter: p = 0.214, long diameter: p = 0.311). There were no significant changes in soma surface area (D, p = 0.232), soma volume (E, p = 0.229), and number of primary dendrites (F, p = 0.054) between two groups. Exercise training significantly increased the number of branch points (G, p = 0.009), number of ends (H, p = 0.001), and total dendritic length (I, p < 0.001). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.