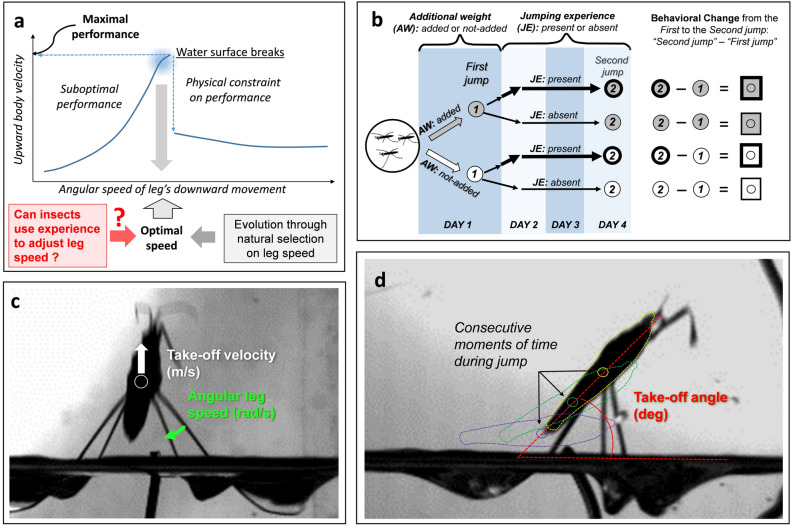

Figure 1.

Research question and methods: the theoretical significance of determining if water striders use their personal experience to adjust their leg speed during jumping on the water surface (a), and the experimental scheme used in the study (b). In (a) According to our recent theoretical model (3), as the angular leg speed increases so is the jumping speed (while the time to take-off decreases; not shown here), until the moment when water surface breaks and jumping performance abruptly decreases. The optimal leg speed is just below that critical value. Water striders are able to maintain, on average, the optimal leg speed, and determining if they are able to modify their leg movements based on personal experience is the first step to evaluate if individual adjustments may be responsible for this optimal behaviour. In (b) on DAY 1, individual water strider of Gerris latiabdominis was randomly assigned to two Additional Weight (AW) treatments: weight-added (gray box) or weight-not-added (white box) treatment. First jump was filmed about two hours after weight addition on DAY 1. Change in jumping performance was expressed as the difference between First jump and Second jump (value at Second jump minus value at First jump) filmed three days later after some individuals had an opportunity to experience frequent jumping (Jumping Experience [JE]-present condition; box plots with thick lines), while others did not (JE-absent condition; box plots with thin lines). (c) and (d) contain graphical conceptualizations of the three response variables: take off velocity (c), angular leg speed (c) and take-off angle (d).