Abstract

Introduction

There are no publicly available national data on healthcare worker infections in Australia. It has been documented in many countries that healthcare workers (HCW) are at increased occupational risk of COVID-19. We aimed to estimate the burden of COVID-19 on Australia HCW and the health system by obtaining and organizing data on HCW infections, analyzing national HCW cases in regards to occupational risk and analyzing healthcare outbreak.

Methods

We searched government reports and websites and media reports to create a comprehensive line listing of Australian HCW infections and nosocomial outbreaks between January 25th and July 8th, 2020. A line list of HCW related COVID-19 reported cases was created and enhanced by matching data extracted from media reports of healthcare related COVID-19 relevant outbreaks and reports, using matching criteria. Rates of infections and odds ratios (ORs) for HCW were calculated per state, by comparing overall cases to HCW cases. To investigate the sources of infection amongst HCW, transmission data were collated and graphed to show distribution of sources.

Results

We identified 36 hospital outbreaks or HCW infection reports between January 25th and July 8th, 2020. According to our estimates, at least 536 HCW in Australia had been infected with COVID-19, comprising 6.03% of all reported infections. The rate of HCW infection was 90/100000 and of community infection 34/100,000. HCW were 2.69 times more likely to contract COVID-19 (95% CI 2.48 to 2.93; P < 0.001). The timing of hospital outbreaks did not always correspond to community peaks. Where data were available, a total of 131 HCW across 21 outbreaks led to 1656 HCW being furloughed for quarantine. In one outbreak, one hospital was closed and 1200 HCW quarantined.

Conclusion

The study shows that HCW were at nearly 3 times the risk of infection. Of concern, this nearly tripling of risk occurred during a period of low community prevalence suggesting failures at multiple hazard levels including PPE policies within the work environment. Even in a country with relatively good control of COVID-19, HCW are at greater risk of infection than the general community and nosocomial outbreaks can have substantial effects on workforce capacity by the quarantine of numerous HCW during an outbreak. The occurrence of hospital outbreaks even when community incidence was low highlights the high risk setting that hospitals present. Australia faced a resurgence of COVID-19 after the study period, with multiple hospital outbreaks. We recommend formal reporting of HCW infections, testing protocols for nosocomial outbreaks, cohorting of workforce to minimize the impact, and improved PPE guidelines to provide precautionary and optimal protection for HCW.

Keywords: COVID-19, Healthcare worker, Healthcare worker infections, Occupational risk

What is already known about the topic?

-

•

The absence of formal national reporting of HCW infections makes it difficult to inform work health and safety of HCW.

-

•

COVID-19 infections have been estimated at greater than 150 000 in HCW Europe alone by June, 2020 (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2020), with over 620 HCW deaths (European Public Service Union 2020). United States of America has seen over 19 000 HCW infections with close to 400 HCW deaths in the same time period.

What this paper adds

-

•

We estimated the burden of COVID-19 in Australian HCW and health systems from publicly available media reports and state press releases data, identifying at least 36 outbreaks in health care facilities and at least 536 HCW infections up to July 8th, 2020. The burden of COVID-19 extended beyond the individual HCW, and resulted in the closure of two hospitals, and in most cases, quarantine of many HCW contacts.

1. Introduction

As of 11th July, over 12 million cases of COVID-19 had been confirmed worldwide, causing more than 548,000 deaths (World Health Organization 2019), with global COVID-19 healthcare worker (HCW) infections on the rise. By early March 2020, more than 3300 HCW had been infected in China alone, with reports of at least 22 HCW deaths (Zhan et al., 2020). In Italy, a country with a high burden of COVID-19, over 20% of responding HCW were infected, with almost 200 HCW deaths (Lapolla et al., 2020; Lancet, 2020). The International Council of Nurses (ICN) has reported that more than 600 nurses have died in the COVID-19 pandemic and estimate that over 450,000 HCW had been infected by June 3rd, 2020 (International Council Nurses 2020). The number of global HCW infections may be underreported due to many countries' state health departments not tracking deaths and infections by occupation (Martin, 2020).

The precise dynamics of transmission of COVID-19 is unknown, but likely through a combination of droplets, aerosols and contact (Chan et al., 2020; Morawska and Milton, 2020). Frontline HCWs, such as those working in emergency wards, are at increased risk as HCW are often exposed to patients with high viral loads whilst providing care (Santarpia et al., 2020) and accumulated respiratory aerosols in the work-place may pose a risk to occupational safety. Hospitals are highly contaminated environments (Santarpia et al., 2020) and hazard controls including PPE are often compromised. In the UK, where testing was done in two National Health System (NHS) trusts, almost one in five HCW were infected (Hunter et al., 2020; Keeley et al., 2020). Therefore, given the hospital as a site of potential outbreaks, infected HCW may be asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic, and unknowingly infect others at work. A study of HCW infections in Wuhan, China, found that the case infection rate of HCW was 2.0%, significantly higher than non-HCW at 0.43% (Zheng et al., 2020).

An analysis of the COVID-19 HCW infections in China during the initial phase of the pandemic, found that a high number of HCW cases occurred through contact with asymptomatic patients or mildly symptomatic patients of COVID-19 and through direct contact between HCW (Tang et al., 2020). A surgical patient in a Wuhan hospital infected 14 HCW before fever onset (World Health Organization 2020). HCW may therefore unknowingly acquire and transmit infections to patients and other HCW around them. Many studies have also shown that hospitals not only present a high exposure setting for respiratory infections in HCW (MacIntyre et al., 2017; Macintyre et al., 2014) but that presenteeism is a key risk factor in disease transmission and extension of an outbreak (Widera et al., 2010). An employee who attends work regardless of having a medical illness which prevents them from functioning optimally demonstrates presenteesim (Widera et al., 2010). Despite the serious public health risks of presenteeism (Forsythe et al., 1999), HCW have been identified as a group that are very likely to continue to work when infected with diseases such as influenza and norovirus (LaVela et al., 2007). In addition, asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic infection can result in nosocomial outbreaks as HCW may work without realizing they are infected.

Shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) have been described as a contributing risk factor for COVID-19 in HCW worldwide (Lapolla et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Australian Government Department of Health, 2020). Initial recommendations from the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were to use respirators, but following a shortage in supply of these, guidelines changed to the use of medical masks, or even cloth masks (Chughtai et al., 2020; Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2020). In China, HCW infections decreased with the increase in acquired PPE along with proper training and make-shift hospitals where patients were categorized and separated according to symptoms (Tang et al., 2020). Following a resurgence in the State of Victoria in July, staff in all clinical areas at the Royal Melbourne Hospital in Parkville, the Northern Hospital in Epping, the Austin Hospital in Heidelberg and The Alfred hospital in Melbourne were advised to wear masks (Cunningham, 2020). However, HCW working in major Sydney and Melbourne hospitals have accused hospital administrators of intimidation of those who demand protective masks whilst on duty (McCauley, 2020). Further to this, there is always the concern of the risk that health system surge could outweigh supply of HCW in hotspots that emerge during the pandemic (Wynne and Ferguson, 2020).

Whilst COVID-19 HCW infections were estimated at greater than over 19 000 cases in the United States of America and over 150 000 cases in Europe (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2020; European Public Service Union 2020; Hunter et al., 2020; Keeley et al., 2020) by July, in the absence of national reporting of HCW infections, the impact of COVID-19 on HCW in Australia needs to be investigated (Hunter et al., 2020; Keeley et al., 2020). The aim of the study was to estimate the burden of COVID-19 on Australian HCW and the national health system using publicly available data.

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection and data linkage

Although there is no national reporting of HCW infections, daily press releases from government sources and media reports have reported on hospital outbreaks and HCW infections. We collected publicly available data on Australian COVID-19 patients reported by National and state/territory Governments and the media between January 25th, 2020 and July 8th, 2020. HCW cases were those with a diagnosis based on positive viral nucleic acid test results on throat swab samples. A line list of HCW related COVID-19 reported cases was created by compiling data obtained from searching the Australian Government Department of Health (DOH) (Coronavirus 2020) and individual state/territory Health Departments daily COVID-19 press releases (NSW Department of Health 2020; Queensland Government 2020; Tasmanian Government Department of Health 2020; Victoria State Government; Health and Human Services 2020; Government of South Australia 2020; Government of Western Australia Department of Health 2020; Northern Territory Government 2020; ACT Government 2020; Victoria State Government 2020; Government of Tasmania 2020) for officially reported individual cases in clinical settings or those where a HCW was infected, and related outbreaks.

For the purposes of this study, Australian HCW were defined as clinical HCW as defined by registration for practice by The Australian Health Practitioners Registration Authority (AHPRA) (AHPRA and National Boards 2020, Medical board: Statistics 2020) and who worked in any clinical setting during the COVID-19 pandemic. This included doctors, nurses, allied health and paramedics (refer to Addendum 1). Data were updated daily between January 25th, 2020 and July 8th, 2020, and no identifying information was available or recorded. Date of COVID-19 confirmation was recorded as a proxy for onset date. A line list of hospital outbreaks was also created.

To enhance the data set, data were extracted from media reports of HCW related COVID-19 cases (Appendix). A Google search was conducted throughout May 20th, 2020 and July 8th, 2020 using the following keywords: “clinical covid [state name]”, “nurse covid [state name]”, “doctor covid [state name]”, “health worker [state name]”, “healthcare worker [state name]”, “paramedic [state name]” where [state name] is repeated for Australia and all states and territories (New South Wales - NSW, South Australia - SA, Western Australia - WA, Tasmania - TAS, Victoria – VIC, Queensland - QLD, Northern Territory – NT and Australian Capital Territory - ACT). The first 3 pages of each Google search were reviewed.

For the line list of outbreaks where an outbreak is defined as 2 or more cases of COVID-19 in a one week period, outbreak information was matched using date, location (state/territory and city), the name of the clinical facility, number of cases, patient age, number of deaths and occupation as an HCW. Matching criteria were used to match information from the media to relevant outbreaks and reports. Matched outbreaks included in this report were detailed in state media releases and thus were recorded in the line list.

HCW cases from media reports were matched with HCW cases recorded in the line list based on the matching criteria matrix in Table 1 . A case was considered a high probability match if fulfilling at least one criterion from all groups (1, 2 and 3); a medium probability match if fulfilling at least one criterion from groups 2 and 3; and otherwise a low probability match. Only cases with high probability matching were included for the line list and analysis. For the purposes of this study, clinical facilities were deidentified in reporting the results.

Table 1.

High, medium, and low probability matching criteria for matching HCW related COVID-19 cases. Criteria for High (At least 1 criterion from Groups 1, 2 and 3); Medium (Any criteria from Groups 2 and 3); Low (Any criteria from Groups 1 and 3) are detailed.

| Group 1: Demographics | Group 2: Location | Group 3: Clinical details |

|---|---|---|

| Age | State | Name of clinical facility |

| Gender | City/Address | Name of clinical facility + suburb |

| Occupation (HCW) |

To investigate the sources of infection amongst HCW, transmission data obtained from further media reports (Appendix) were collated and categorized based on whether the person who was the initial source of infection (index case) was identified or not, and if so, had travelled overseas, contracted COVID-19 in a clinical setting, or was a local case without any confirmed epidemiological linkage. These data were graphed to show distribution of sources. For each clinical outbreak identified, the number of staff in self quarantine, number of secondary related COVID-19 infections and facility shutdown was recorded to determine the impact of COVID-19 on the healthcare system and workforce capacity (Appendix). The ratio of staff in quarantine to the number of positive cases nationwide was calculated.

2.2. Data analysis

Rates of infection for HCW were calculated using reported cases and the remaining total cases as the numerator, and denominator data was obtained from the Australian Government (Coronavirus 2020) and AHPRA (AHPRA and National Boards 2020; Medical board: Statistics 2020). There were 594,283 registered HCW in Australia in 2019 (AHPRA and National Boards 2020; Medical board: Statistics 2020). We calculated rate of infection in HCW compared to the community for the study time period using the reported cases in HCW compared to the community, with denominator data being the number of registered practitioners on AHPRA and the population of Australia (24.99 million). The Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated by comparing total cases in the general population per state to HCW cases to analyze if the risk of infection associated with HCW is higher than the general population.

We identified 536 HCW infections reported nationally by July 8th, 2020, data for only 241 of these cases outbreaks were matched to outbreaks, and these were obtained used for the line list. An epidemic curve was plotted to describe the distribution of HCW cases for both isolated cases and outbreaks against Australia's nationwide epidemic curve.

To check if diagnosis is proportionate to testing, daily testing data for each state for all COVID-19 tests performed were collected from individual state/territory Health Departments (Victoria State Government; Health and Human Services 2020; Northern Territory Government 2020; Government of Tasmania 2020; Coronavirus 2020; NSW Government 2020; Government of South Australia 2020; Queensland Government 2020; Government of Western Australia Department of Health 2020) and plotted alongside HCW related COVID-19 cases. Key dates relating to government control measures were overlaid to aid interpretation.

Occupational risk level was assigned for each outbreak based on the context during which the first HCW case acquired the infection. The exposure was considered high if the HCW acquired COVID-19 while working in clinical duties that involved direct exposure to COVID-19 patients, or working in settings that featured a high daily influx of patients such as Emergency Departments or Paramedic Ambulances (i.e. pre-hospital), intensive care units (ICU), acute medical wards and any clinical environment with a positive COVID-19 patient; medium if the HCW acquired COVID-19 whilst working clinical duties in other settings beside those in the High level; and low if the HCW acquired COVID-19 out of work, or whist working non-clinical duties, or duties that did not involve direct contact with patients and patients' biological samples.

Analysis and reporting were based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for epidemiological studies (von Elm et al., 2007). The data generated from this study were cleaned prior to analysis and presented using descriptive statistics after analysis with Stata IC version 16.1 (College Station, 2019). A Chi-square test was used to calculate the OR.

3. Results

3.1. Australian HCW COVID-19 analysis

On July 8th, 2020, a total of 8,886 confirmed COVID-19 cases including 106 deaths, were recorded nationwide as reported by the Australian Department of Health (DOH) (Laschon, 2020). We estimated 536 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in HCW identified between January 20th and July 8th, 2020, comprising 6.03% of all COVID-19 cases reported nationwide. The rate of HCW infection was 90/100,000 and of community infection 34/100,000. COVID-19 HCW infections made up over 38% (n=86) of the total number of cases in Tasmania, whilst 7% (n=218) of the COVID-19 cases in Victoria were HCW. High rates of HCW infections were seen in Tasmania (903.84/100,000) and Victoria (148.64/100,000). Analysis of nationwide reported HCW COVID-19 cases revealed that HCW were 2.69 times more likely to contract COVID-19 (95% CI 2.48 to 2.93; P<0.001) than the general community whose rate of infection was 30/100,000 (Table 2 ). Tasmanian HCW, where a single outbreak resulted in 82 HCW infections, were 24.70 times more likely to contract COVID-19 (95% CI 20.61 to 29.61; P<0.001). Similarly, in New South Wales, with over 200 reported HCW infections, HCW were 3.48 times more likely to contract COVID-19 as compared to the general population (95% CI 3.06 to 9.68, P<0.001). A statistically significant association was also seen in Victoria (95% CI 2.94 to 3.82; P<0.001) where HCW were 3.35 times more likely to contract COVID-19. Lastly, HCW did not have a significant risk of infection in South Australia and Queensland, and the risk was significantly lower in Queensland. One HCW death was reported in Melbourne, Victoria, a disability nurse (Aubusson, 2020).

Table 2.

Analysis of reported confirmed COVID-19 infections in HCW per state territory, in Australia as of July 8th, 2020, 2020 (n=536).

| State/Territory | Prevalence (per 100,000) | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WA (n=14) | 25.79 | 1.09 | 0.64 to 1.85 | P=0.752 |

| SA (n=2) | 4.48 | 0.18 | 0.05 to 0.60 | P=0.005* |

| NSW (n=208) | 133.71 | 3.49 | 3.06 to 9.68 | P<0.001* |

| TAS (n=86) | 903.84 | 24.70 | 20.61 to 29.61 | P<0.001* |

| QLD (n=8) | 6.96 | 0.33 | 0.17 to 0.64 | P<0.001* |

| VIC (n=218) | 148.64 | 3.35 | 2.94 to 3.82 | P<0.001* |

| National HCW (n=536) | 90.19 | 2.76 | 2.53 to 3.01 | P<0.001* |

Statistically significant.

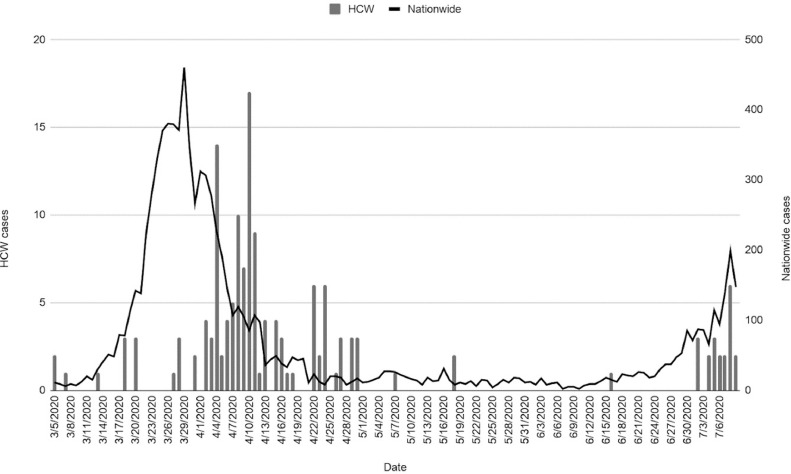

Fig. 1 summarizes the epidemic curve of HCW cases reported by the states’ departments of health and the media from January 25th, 2020 to July 8th, 2020. Although the overall COVID-19 epidemic curve peaks on March 23rd and 27th, 2020, the epidemic curve for HCW cases only peaks within the subsequent two-week period, on April 3rd and April 9th, 2020. Notably, the North-West Regional Hospital/North-West Private Hospital outbreak consistently reported HCW cases from April 3rd to April 29th, 2020. Although the overall epidemic curve for Australia started to flatten in early April, HCW cases persisted until May 19th, 2020. The second wave of COVID-19 in Melbourne also saw a rise in HCW infections after late June 2020.

Fig. 1.

The left y-axis shows the daily number of HCW COVID-19 cases nationwide. The right y-axis shows the total number of confirmed daily COVID-19 cases nationwide. Date of COVID-19 confirmation is used as a proxy for onset.

3.2. COVID-19 tests and HCW infections

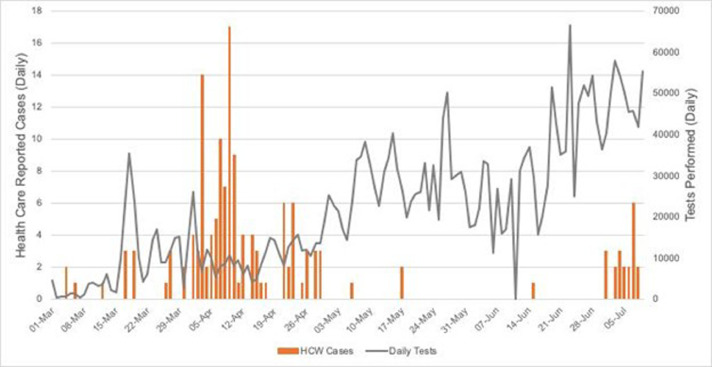

Fig. 2 shows the number of HCW cases in relation to the number of daily COVID-19 tests performed nationwide. Peaks in reported HCW cases also coincide with changes to the testing criteria implemented both nationwide and per state/territory, which occurred on March 25th, 2020 to eliminate the requirement of recent travel in the criteria to test. The criteria at that time restricted testing to those symptomatic with a fever. Since this national guideline in April, some individual states revised their policies based on the local epidemiology to include the testing of asymptomatic HCW. Additionally, to increase awareness of the prevalence of COVID-19 in the general population, NSW implemented a two-week testing campaign from April 27th, 2020 (NSW Department of Health 2020). Similarly, Victoria implemented a testing campaign from the May 1st, 2020 (Victoria State Government; Health and Human Services 2020), and again during the resurgence in early July, 2020, whilst SA implemented a testing campaign from May 16th, 2020 to May 30th, 2020 (Government of South Australia 2020). The ramp up in the numbers of testing occurred after the highest numbers of HCW cases were reported. March 25th’s nationwide expansion of testing criteria allowed all individuals exhibiting common symptoms of COVID-19 to be tested, not just those exhibiting symptoms that had traveled overseas or close contacts of a case. Prior to the adoption of the new criteria, 10 HCW cases were confirmed. However, expansion of the testing criteria identified significantly more HCW cases, contributing to the idea that testing amongst HCW nationally needs increasing.

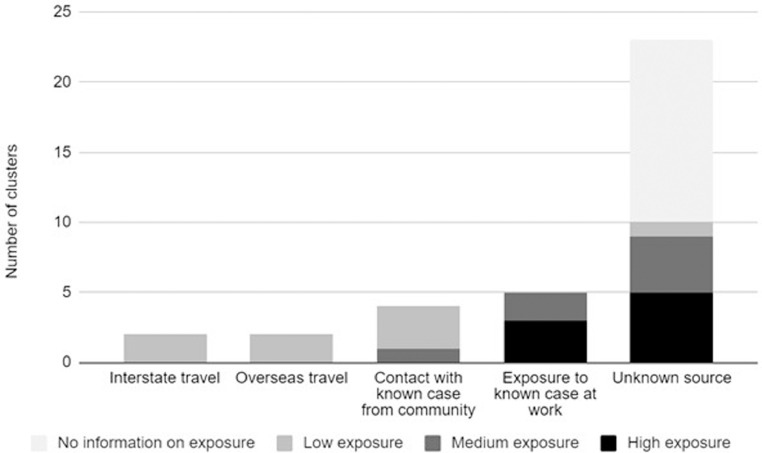

Fig. 3.

Frequency distribution of sources of COVID-19 infection among reported HCW outbreaks/cases. Risk is stratified based on occupational risk level as defined above.

Fig. 2.

The left y-axis shows the total number of confirmed HCW COVID-19 cases nationwide. The right y-axis shows the number of daily COVID-19 tests nationwide. Date of COVID-19 confirmation is used as a proxy for onset. a – Only overseas return travelers were tested. March 17th, QLD and ACT started regularly reporting testing data; b - March 25th, indicates a nationwide change in testing criteria to include people who did not recently travel from overseas; c - May 1st, indicates a change in reporting from people tested to number of tests performed in WA; d - May 26/27th: indicates a change in reporting from people tested to number of tests performed in NSW and VIC.

3.3. Sources of infection among HCW

Out of 36 hospital outbreaks identified from the media, 2 (5.56%) started with a HCW that travelled interstate; 2 (5.56%) started with a HCW that returned from overseas; 4 (11.11%) started with a HCW that was a contact of a known case from a community outbreak; 5 (13.89%) were traced to contact with a patient that had tested positive for COVID-19, and 22 (61.11%) did not have information on the source of infection.

Based on the setting in which the first HCW case was working on when they acquired COVID-19, 8 outbreaks (22.2%) were considered high occupational exposure risk, 7 (19.4%) medium exposure risk, 8 (22.2%) low exposure risk and 13 (36.1%) did not have information to assess risk level. Among the 8 high-risk outbreaks, 3 involved emergency departments or infectious disease units, 2 involved paramedics and ambulances, 1 involved a quarantine zone for returning travelers and 1 involved direct exposure to COVID-19 patients from a cruise ship. Descriptive information for HCW outbreaks is outlined in Table 3 in the Appendix.

Table 3.

Covid-19 HCW outbreaks between January 20th, 2020 and July 8th, 2020.

| De-Identified Outbreak | State | Number of infected HCWs |

Setting | Occupational risk level⁎⁎⁎ |

Description of index case | Number of staff in self-isolation |

Number of secondary non-HCW cases |

Number of deaths associated with outbreak* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (Ferguson, 2020, Government of Tasmania 2020, Guardian Staff 2020) | TAS | 82 | Hospital – various wards | High | Exposed to 2 patients from Ruby Princess cruise ship, admitted on 20/3 and 26/3. First case notified on 3/4 but several staff had already experienced symptoms by then. |

1200 | 41 | 5⁎⁎ |

| B (Guardian Staff 2020, Chapman, 2020) | VIC | 10 | Hospital – haematology & oncology ward |

Medium | Detected through contact tracing after 4 inpatients tested positive |

100 | 5 | 3 |

| C (NSW Department of Health 2020, Guardian Staff 2020) |

NSW | 6 | Hospital – unspecified | N/A | No further information | Unspecified | 7 | 1 |

| D (Lynch, 2020) | QLD | 5 | Hospital – pathology lab technicians | Low | Tested positive after returning from Brisbane |

80 | 0 | 0 |

| E (Cunningham, 2020, Victoria State Government; Health and Human Services 2020) | VIC | 5 | Hospital - psychiatrists | Medium | No further information | Unspecified | 9 | 0 |

| F (Victoria State Government 2020) | VIC | 2 | Hospital – emergency ward | High | Exposed to patient who was from an identified community outbreak and later tested positive |

24 | Unspecified | 0 |

| G (Aubusson, 2020, NSW Department of Health 2020) | NSW | 2 | Hospital – radiation therapists | Medium | No further information | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| H (May, 2020) | WA | 2 | Hospital – maternity ward | Medium | No further information | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| I (Laschon, 2020) | WA | 2 | Hospital – psychiatric unit | Low | Developed symptoms after returning from overseas |

13 | 0 | 0 |

| J (NSW Department of Health 2020) | NSW | 1 | Hospital – unspecified | N/A | No further information | Unspecified | 0 | 0 |

| K (Government of Western Australia Department of Health 2020) | WA | 1 | Hospital – unspecified | Low | History of intrastate travel | Unspecified | 0 | 0 |

| L (NSW Department of Health 2020) | NSW | 1 | Hospital – unspecified | N/A | No further information | 23 | 6 | 0 |

| M (Kagi, 2020) | WA | 2 | Hospital – unspecified | N/A | No further information | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| N (Tasmanian Government Department of Health 2020) | TAS | 1 | Hospital – unspecified | N/A | No further information | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| O (NSW Department of Health 2020) | NSW | 1 | Hospital – unspecified | Low | Attended a medical conference with another case |

28 | 0 | 0 |

| P (Tasmanian Government Department of Health 2020, Guardian Staff 2020) |

TAS | 1 | Hospital – unspecified | N/A | No further information | Unspecified | Unspecified | 4 |

| Q (Chain and Ferry, 2020) | NSW | 1 | Hospital – unspecified | Low | Worked non-clinical duties at two hospitals |

10 | Unspecified | 0 |

| R (Central Western Daily, 2020) | NSW | 1 | Hospital – unspecified | N/A | No further information | 0 | Unspecified | 0 |

| S (Guardian Staff 2020, Writer, 2020) | WA | 1 | Hospital - emergency department | High | No further information | 0 | Unspecified | 3 |

| T (Queensland Government 2020) | QLD | 1 | Hospital – infectious disease unit | High | No further information | 6 | Unspecified | 0 |

| U (Olle, 2020) | SA | 1 | Hospital – ICU | Medium | Tested positive after developing symptoms |

22 | Unspecified | 0 |

| V (Mail Times, 2020) | WA | 1 | Hospital - unspecified | N/A | No further information | 22 | Unspecified | 0 |

| W (NSW Department of Health 2020) | NSW | 1 | Hospital – unspecified | Low | Attended a medical conference with another case |

61 | 1 | 0 |

| X (Woolley, 2020) | NSW | 1 | Hospital – maternity ward | Medium | No further information | Unspecified | Unspecified | 0 |

| Y (NSW Department of Health 2020) | NSW | 1 | Community – Paramedic | High | No further information | Unspecified | Unspecified | 0 |

| Z (Law, 2020) | WA | 1 | Hospital - unspecified | Low | Tested positive after returning from US |

Unspecified | Unspecified | 0 |

| AA (Godfrey, 2020) | VIC | 1 | Community – quarantine hotel | High | Undertaking duties at quarantine location |

0 | 0 | 0 |

| AB (Woolley, 2020) | VIC | 1 | Hospital - unspecified | N/A | No further information | Unspecified | Unspecified | 0 |

| AC (Victoria State Government; Health and Human Services 2020) | VIC | 10 | Hospital – acute medical ward | N/A | No further information | 15 | Unspecified | 0 |

| AD (Victoria State Government; Health and Human Services 2020) | VIC | 1 | Hospital - unspecified | N/A | No further information | Unspecified | Unspecified | 0 |

| AE26 | VIC | 2 | Hospital – unspecified | Low | Close contact of a confirmed case; attended a group training session in hospital |

Unspecified | Unspecified | 0 |

| AF (Beers, 2020) | VIC | 8 | Hospital – emergency department | N/A | No further information | All other staff in department | 1 | 0 |

| AG (Woolley, 2020) | VIC | 1 | Hospital – unspecified | N/A | No further information | Unspecified | Unspecified | 0 |

| AH (Victoria State Government; Health and Human Services 2020) | VIC | 1 | Hospital – unspecified | Medium | Exposed to a patient who later tested positive |

Unspecified | 2 | 0 |

| AI (Beers, 2020) | VIC | 1 | Hospital – unspecified | N/A | No further information | Unspecified | 4 | 0 |

| AK (Olle, 2020) | VIC | 4 | Community – paramedics | High | No further information | Unspecified | Unspecified | 0 |

Includes both HCW and non-HCW deaths that were epidemiologically linked to the outbreak.

Only deaths that occurred within the premises of North West Regional Hospital and North West Private Hospital are counted. As patients from these hospitals were transferred to other hospitals on April 12th, 2020, death count for this outbreak may be underestimated (ABC News, 2020).

Occupational risk is not assigned if no information is available about the ward and the specialty of the HCW, and the context during which the HCW acquired Covid-19.

High level if the HCW acquires Covid-19 while working clinical duties that involve direct exposure to Covid-19 patients or working in settings that feature a high daily influx of patients such as Emergency Departments or Paramedic Ambulances.

Medium level if the HCW acquires Covid-19 while working clinical duties in other settings beside those in High level.

Low level if the HCW acquires Covid-19 out of work, or while working in non-clinical duties, or duties that do not involve direct contact with patients and patients' biological samples.

3.4. Quarantine of HCW during COVID-19 outbreaks in clinical settings

One way to measure the burden of COVID-19 infections on the health system is to measure the ratio of the number of HCW being quarantined because of contact with a known case, to the number of positive cases. Table 4 shows outbreaks with the highest ratio of quarantine to positive cases, all but one of whom only had 1-2 positive cases. In a hospital in NSW, one confirmed case of COVID-19 in a doctor led to 61 staff members being isolated, effectively removing them from the health care system for 14 days. The outbreak in = two hospitals in Tasmania was the largest known HCW outbreak in the nation in the study period, resulting in 1,200 staff members being forced to isolate and a complete shut-down of both hospitals. Most patients from both hospitals - a combined capacity of 261 beds - were transferred to a community hospital, which placed a significant burden on the capacity of this smaller, 95-bed hospital. In outbreaks identified with a ratio of quarantine to positive cases, >61 facilities or wards were not shut down. The factors that might explain the disparity in the ratios include the type of acute care facilities that may not be able to be shut down (such as emergency departments) and availability of HCW to replace those in quarantine.

Table 4.

The burden of COVID-19 infections amongst HCW on the healthcare system. Medical Facilities associated with a COVID-19 positive HCW are listed. The ratio of staff in quarantine to the number of positive cases nationwide is included.

| Deidentified Medical Facility | Number of confirmed HCW cases | Number of staff in quarantine | Ratio of HCW in quarantine/ case | Facility/ward shut down (temporary shutdown included) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X l (NSW Department of Health 2020, Seo, 2020) | 1 | 61 | 61 | No |

| P (NSW Department of Health 2020, Seo, 2020) | 1 | 28 | 28 | No |

| L (NSW Department of Health 2020, Seo, 2020) | 1 | 23 | 23 | No |

| V (World Health Organization 2019, Seo, 2020) | 1 | 22 | 22 | No |

| D (Lynch, 2020) | 1 | 80 | 80 | Yes |

| A (Government of Tasmania 2020, Ferguson, 2020) | 84 | 1200 | 14.3 | Yes |

| I (Laschon, 2020) | 1 | 13 | 13 | No |

| F (Boseley, 2020) | 2 | 24 | 12 | No |

| AD (Victoria State Government; Health and Human Services 2020) | 1 | 15 | 15 | No |

4. Discussion

In the absence of formally reported statistics on HCW infections, we estimated a minimum of 536 HCW infections up to July 2020, and that HCW accounted for 6.03% of COVID-19 infections in Australia and have almost three times the risk of contracting COVID-19 than the general community. The numbers we estimate are consistent with Federal government press releases that there were 481 HCW infections by April 2020, released well after nthe epidemic peak of the first wave in March 2020 (Cohen and Day, 2020). The higher risk of infection is consistent with studies overseas which show a higher risk for HCW (Hunter et al., 2020; Keeley et al., 2020).

A potential limitation of the analyses conducted for this study were based on open-sourced data for HCW cases, which may vary depending on each state's individual data publishing policies. Therefore the study probably presents minimal estimates of HCW infections. We also used media reports, which have not been verified. In most cases, however, there were multiple media reports about each outbreak, often with quotes from health officials. There is also a potential effect of testing rates on the identification of COVID-19 cases. We accounted for this by representing the daily testing rates in conjunction with the daily HCW infections reported. The source of infection for 22 of the 36 outbreaks analyzed could not be identified from the available information. The occupational risk level for the 36 outbreaks is therefore uncertain. The study did not include the second much larger wave of COVID-19 which occurred in the State of Victoria in July 2020, where over 3500 HCW were infected (Victoria State Government Health and Human Services 2020; Buising et al., 2020). Therefore, this study may not be generalizable to the period July-August 2020. It may not be generalizable to other countries or settings, with different COVID-19 epidemiology and health systems.

Nosocomial outbreaks of SARS and SARS-COV-2 have been described (Campbell, 2006), showing hospitals to be a high risk setting for outbreaks. HCW may become infected from COVID-19 patients, co-workers or from outside the hospital, and may act as vectors for onward transmission to co-workers, patients and community members including household contacts. There are some HCWs who have continued to work while symptomatic and some may be asymptomatically infected and working. Our analysis shows that the source of hospital outbreaks can be from both COVID-19 patients and from infections imported into the hospital by HCW or others. Undiagnosed COVID-19 patients (Baker et al., 2020) and undiagnosed HCW may both cause transmission in the hospital setting.

The largest COVID-19 HCW outbreak in the study period occurred during the first few weeks of the Australian pandemic when community transmission was low and testing of HCW was based on symptoms. This indicates the importance of tightening hazard control measures in hospitals (e.g. telehealth, foot traffic controls, ventilation, PPE) and considering a lower threshold for testing of HCW. With respect to PPE, at the time hospitals guidelines recommended surgical masks for HCW seeing confirmed or suspected COVID-19 patients based on national guidelines (ICEG) (MacIntyre et al., 2020). Universal mask use inside hospitals was also not widespread until the second wave in Victoria. The first peak in HCW infections nationwide occurred before the expansion of testing by national state territories during April 2020 (Australian Government Department of Health 2020) that included those with all cold-like symptoms. Expansion of the testing criteria identified 183 more HCW cases, supporting a low threshold for testing HCW. The consequences to the health system of HCW infections can be significant. We showed the potential depletion of the workforce due to required quarantine and even closures of hospitals (such as in Tasmania) in Table 4. The impact of these closures strains the health system and has implications for secondary transmission. This may also have implications for the welfare of remaining HCW. The outbreak in the Tasmanian Hospitals of 82 HCW infections resulted in 1,200 staff members who were required to isolate, leading to a complete shut-down of both hospitals. Globally, it has been estimated that 125,000 HCW have been forced to self-isolate due to a lack of effective testing (Woodcock, 2020) by July. Mass testing of HCW should be considered as part of a suite of measures to relieve the healthcare system and protect the healthcare workforce (Black et al., 2020).

We showed that HCW infections do not always correspond with high community transmission, which is another line of evidence supporting the unique risk in hospitals. This study suggests suggeststhat many Australian HCW infections are contracted in a clinical setting. Similarly, a study of American health providers infections found that over 50% of COVID-19 infections were contracted through clinical settings (CDC COVID-19 Response Team 2020). Unprotected and repeated exposures in high risk environments which are known to be heavily contaminated, such as clinical settings, results in a high incidence of HCW infections (Woodcock, 2020). Contributing to this risk, is the fact that asymptomatic persons are potential sources of COVID-19 infection (Rothe et al., 2020). Around 40 to 45% of COVID-19 cases are asymptomatic (Oran and Topol, 2020; Byambasuren et al., 2020). Whilst we did not have data on whether HCW were furloughed with or without pay, this could also affect presenteeism and outbreak spread.

Shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) have been described as a significant contributing risk factor for COVID-19 in HCW worldwide (Lapolla et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020). Infection control training and use of PPE have been associated with decreased risk of COVID-19 infection (Chou et al., 2020). The PPE guidelines for Australia specify that a surgical mask must be used for routine care of COVID-19 patients (Australian Government Department of Health 2020). With increasing evidence of airborne or aerosol potential for SARS-COV-2 (Morawska and Milton, 2020, Santarpia et al., 2020; Chia et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020), it is important to review these guidelines and invoke the precautionary principle for protection of HCW from occupational risk (MacIntyre et al., 2020). PPE guidelines did not change during the study time period and continued to recommend a surgical mask for care of COVID-19 patients, with a N95 only for aerosol generating procedures. Subsequently in July 2020, during the second wave in Victoria when over 3000 health workers became infected (Victoria State Government Health and Human Services 2020; Buising et al., 2020), the state guidelines were changed to recommend N95 respirators for care of COVID-19 patients. The inquiry into HCW infections and deaths following the SARS epidemic in Toronto concluded that failure to use the precautionary principle while experts were arguing about droplet or airborne transmission, resulted in preventable HCW infections and deaths (Campbell, 2006). In Victoria in October 2020, following the end of the large second wave, a community outbreak was linked to a hospital as the source.

5. Conclusion

HCW and the health system experience significant burden from COVID-19. Near tripling of the risk of infection in HCW during a period of low community transmission suggests failures at multiple hazard control levels including PPE in the workplace. Consideration should be given to strengthening PPE recommendations and other hazard control measures including ventilation, universal mask use and mass testing of staff. In the State of Victoria, a second wave caused over 3500 HCW infections (Victoria State Government Health and Human Services 2020; Buising et al., 2020), and resulted in a change in state guidelines to recommend N95 respirators for care of COVID-19 patients. With control of the second wave and the easing of restrictions, health facilities may continue to pose a risk of outbreaks. In light of a resurgence of COVID-19 in Victoria in late June 2020 and multiple hospital outbreaks affecting HCW, it is critical to have formal reporting of HCW infections, testing protocols, cohorting of workforce to minimize the impact, and improved PPE guidelines.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ashley L. Quigley: Writing - original draft, Project administration, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis. Haley Stone: Methodology, Formal analysis. Phi Yen Nguyen: Methodology, Formal analysis. Abrar Ahmad Chughtai: Supervision, Writing - review & editing. C. Raina MacIntyre: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgments

None

Appendix

Addendum 1:

Definitions:

HCW were defined as those who have active registration the Medical Board of Australia (Medical board: Statistics 2020). Table x and Table y were used for obtained on March 2020 reports for the given specification of profession. Table x was separated due to the specializations of Medical Doctors stated in within the 2020 report. A final section was added with doctors that have no public private partnerships (PPP) or affiliations. Lastly, Table z takes the total of all categories and subtracts non-practicing medical professionals. Additionally, the numbers reported for the national pandemic response, (a short-term pandemic response sub-register to enable rapid return to the workforce of experienced and qualified health practitioners), were added to the National numbers.

Table x.

Number of medical doctors within Australia used for the analysis of HCW.

| State | Emergency medicine | Intensive care medicine | Obstetrics and gynaecology | Paediatrics and child health | Pathology | Physician | Radiology | Surgery | Acupuncture | Medical practitioners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT | 47 | 25 | 38 | 49 | 51 | 208 | 59 | 102 | 5 | 2282 |

| NSW | 694 | 287 | 611 | 1014 | 749 | 3457 | 772 | 1925 | 162 | 36381 |

| NT | 56 | 11 | 19 | 42 | 11 | 113 | 6 | 40 | 3 | 1426 |

| QLD | 618 | 220 | 430 | 595 | 422 | 2059 | 529 | 1207 | 102 | 24387 |

| SA | 146 | 74 | 155 | 217 | 155 | 935 | 189 | 478 | 32 | 8526 |

| TAS | 65 | 18 | 44 | 51 | 47 | 215 | 50 | 113 | 13 | 2531 |

| VIC | 622 | 241 | 570 | 809 | 491 | 3367 | 692 | 1616 | 240 | 29943 |

| WA | 285 | 91 | 193 | 334 | 243 | 958 | 277 | 515 | 34 | 11992 |

| No PPP | 83 | 42 | 53 | 86 | 47 | 265 | 138 | 126 | N/A | 2183 |

Table y.

Number of remaining HCW within Australia used for in analysis.

| State | Pharmacy | Paramedics | Nursing |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACT | 632 | 289 | 6312 |

| NSW | 9445 | 4875 | 104858 |

| NT | 274 | 186 | 4297 |

| QLD | 6338 | 5089 | 79202 |

| SA | 2240 | 1309 | 32600 |

| TAS | 802 | 479 | 9260 |

| VIC | 8120 | 5532 | 103064 |

| WA | 3391 | 1184 | 37715 |

| No PPP | 261 | 228 | 11374 |

Table z.

National numbers with pandemic response numbers added. This takes the total of all categories and subtracts non practicing medical professionals.

| Medical Practitioners | Pharmacy | Paramedics | Nursing | Pandemic Response | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | 119651 | 31503 | 19171 | 388682 | 35276 |

References

- ABC News. Tasmania Closes Two Hospitals to “Stamp Out” Coronavirus Outbreak in the North-West Key Points. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-12/tasmania-to-close-two-hospitals-due-to-coronavirus-outbreak/12143552. Published 2020. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- ACT Government. ACT government: COVID-19. https://www.covid19.act.gov.au/. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- AHPRA & National Boards. Pandemic response sub-register. https://www.ahpra.gov.au/News/COVID-19/Pandemic-response-sub-register.aspx. Published 2020. Accessed May 25, 2020.

- Aubusson B.K. The Sydney Morning Herald; 2020. Coronavirus Clusters Pervade Australian Hospital Wards.https://www.smh.com.au/national/coronavirus-clusters-pervade-australian-hospital-wards-20200409-p54ip4.html Published Accessed June 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Health . Infection Control Expert Group (ICEG); 2020. Guidance on the Use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in Hospitals During the COVID-19 Outbreak.https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/07/guidance-on-the-use-of-personal-protective-equipment-ppe-in-hospitals-during-the-covid-19-outbreak.pdf Published Accessed July 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Health . 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) - CDNA National Guidelines for Public Health Units.https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/7A8654A8CB144F5FCA2584F8001F91E2/$File/COVID-19-SoNG-v3.4.pdf Published Accessed July 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Health . Coronavirus (COVID-19) Health Alert; 2020. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for the Health Workforce During COVID-19.https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19-advice-for-the-health-and-disability-sector/personal-protective-equipment-ppe-for-the-health-workforce-during-covid-19 Accessed October 10. [Google Scholar]

- Baker M.A., Rhee C., Fiumara K. COVID-19 and the risk to health care workers: a case report. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020;(March):19–20. doi: 10.7326/L20-0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay, S., Ronnie, E.B., Murtaza, K., et al., 2020. Infection and mortality of healthcare workers worldwide from COVID-19: a scoping review. Medrxiv 1–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beers L.M. 7 News. 2020. Brunswick Private Hospital in Melbourne Records Five Coronavirus Cases.https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/brunswick-private-hospital-in-melbourne-records-five-coronavirus-cases–c-1153321 Published Accessed July 9, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Beers LM. Eight coronavirus cases at northern hospital emergency department in epping. https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/eight-coronavirus-cases-at-northern-hospital-emergency-department-in-epping-c-1150443. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- Black J.R.M., Bailey C., Przewrocka J., Dijkstra K.K., Swanton C. COVID-19: the case for health-care worker screening to prevent hospital transmission. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1418–1420. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30917-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boseley M. Australian Asscoiated Press; 2020. Number of Positive Covid-19 Tests from Melbourne Cedar Meats Outbreak Rises to 45. The Guardian; Australia Edition.https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/05/number-of-positive-covid-19-tests-from-melbourne-cedar-meats-outbreak-rises-to-45 Published Accessed June 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Buising K., Williamson D., Cowie B. A hospital-wide response to multiple outbreaks of COVID-19 in health care workers lessons learned from the field. Medrxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.09.02.20186452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byambasuren O., Cardona M., Bell K., Clark J., McLaws M.-L., Glasziou P. Estimating the extent of true asymptomatic COVID-19 and its potential for community transmission: systematic review and meta-analysis. SSRN Electron. J. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3586675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A. Vol 3. 2006. https://collections.ola.org/mon/16000/268478.pdf (A SARS Commission Final Report: Spring of Fear). [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Strategies for optimizing the supply of facemasks: COVID-19 | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/index.html%0Ahttps://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/face-masks.html. Published 2020. Accessed July 12, 2020.

- Central Western Daily. Orange Health Worker Confirmed With Coronavirus, No New Cases with 18 People Recovered in the Western Region. https://www.centralwesterndaily.com.au/story/6714652/orange-health-worker-tests-positive-to-coronavirus-but-no-new-cases-in-region/. Published 2020. Accessed May 24, 2020.

- CDC COVID-19 Response Team Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020;69(15):477–481. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chain B., Ferry L. The Daily Mail Australia; 2020. Ten Workers at Nepean and Sydney Adventist Hospitals Quarantined after Doctor Caught Coronavirus.https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8258071/Ten-workers-Nepean-Sydney-Adventist-Hospitals-quarantined-doctor-caught-coronavirus.html Published Accessed June 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.F.W., Yuan S., Kok K.H. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman A. 7 News; 2020. Coronavirus Cluster at Melbourne Hospital Sends 100 Staff into Self-isolation Key Points.https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-03/victorian-coronavirus-death-in-melbourne-raises-australian-toll/12116298 Published Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chia P.Y., Coleman K.K., Tan Y.K. Detection of air and surface contamination by SARS-CoV-2 in hospital rooms of infected patients. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16670-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou R., Dana T., Buckley D.I., Selph S., Fu R., Totten A.M. Epidemiology of and risk factors for coronavirus infection in health care workers. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/m20-1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chughtai A.A., Seale H., Macintyre C.R. Effectiveness of cloth masks for protection against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.200948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J., Day L. ABC News; 2020. Australian Healthcare Workers Riding the Coronavirus Curve are Relieved as Infections Dwindle.https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-04/coronavirus-frontline-health-workers/12198348 Published Accessed May 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- College Station TSL. StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 16. 2019.

- Coronavirus . Australian Government Department of Health; 2020. (COVID-19) Current Situation and Case Numbers.https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19-current-situation-and-case-numbers%0Ahttp://files/358/coronavirus-covid-19-current-situation-and-case-numbers.html Published Accessed July 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) current situation and case numbers. Australian ministry department of health (DOH). https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19-current-situation-and-case-numbers. Published 2020. Accessed September 1, 2020.

- Cunningham M. “Deeply concerned”: doctor at Melbourne hospital tests positive to coronavirus. The Age. https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/deeply-concerned-doctor-at-melbourne-hospital-tests-positive-to-coronavirus-20200708-p55a2p.html. Published 2020. Accessed July 8, 2020.

- European Public Service Union. Health workers bear brunt of COVID-19 infections. https://www.epsu.org/article/health-workers-bear-brunt-covid-19-infections. Published 2020. Accessed October 8, 2020.

- Ferguson A. The Sydney Morning Herald; 2020. Tasmanian “Ruby Princess” Hospital Hit by COVID-19 Outbreak Warned of Staff, PPE Shortages.https://www.smh.com.au/national/tasmanian-ruby-princess-hospital-hit-by-covid-19-outbreak-warned-of-staff-ppe-shortages-20200507-p54qrj.html%0A Published Accessed June 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe M., Calnan M., Wall B. Doctors as patients: postal survey examining consultants and general practitioners adherence to guidelines. Br. Med. J. 1999;319(7210):605–608. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7210.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey A. 7 News; 2020. Park Royal Hotel Melbourne Health Worker Positive for COVID.https://7news.com.au/travel/coronavirus/park-royal-hotel-melbourne-health-worker-positive-for-covid-c-1145582 Published Accessed July 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of South Australia . SA Health; 2020. Testing for COVID-19: Who can Get Tested.https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/conditions/infectious+diseases/covid+2019/community/testing+for+covid-19 Published Accessed May 31, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of South Australia. Dashboard and daily update. SA.GOV.AU: COVID-19. https://www.covid-19.sa.gov.au/home/dashboard. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- Government of South Australia. SA Media Releases. https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/about+us/news+and+media/all+media+releases?mr-sort=date-desc&mr-pg=1. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- Government of Tasmania . 2020. COVID-19 North West Regional Hospital Outbreak Interim Report.http://health.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/401010/North_West_Regional_Hospital_Outbreak_-_Interim_Report.pdf Published Accessed May 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Tasmania . Media Releases; 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) - Cases and Testing Updates.https://www.coronavirus.tas.gov.au/media-releases Published Accessed May 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Western Australia Department of Health. COVID-19 update – 29 March 2020. Media releases. https://ww2.health.wa.gov.au/Media-releases/2020/COVID19-update-29-March-2020. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Coronavirus COVID-19 in Western Australia. https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/359bca83a1264e3fb8d3b6f0a028d768. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Latest news: media releases. https://ww2.health.wa.gov.au/News/Media-releases-listing-page. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- Guardian Staff . The Guardian; Australia: 2020. Australia's Coronavirus Victims: Covid-19 Related Deaths Across the Country.https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/apr/21/australia-coronavirus-victims-age-names-deaths-covid-19-australian-death-toll Edition. Published Accessed June 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z.D., Wang Z.Y., Zhang S.F. Aerosol and surface distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in hospital wards, Wuhan, China, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26(7):1583–1591. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter E., Price D.A., Murphy E. First experience of COVID-19 screening of health-care workers in England. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):e77–e78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30970-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Council Nurses . ICN News; 2020. More than 600 Nurses Die from COVID-19 Worldwide.https://www.icn.ch/news/more-600-nurses-die-covid-19-worldwide Published Accessed July 8, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kagi J. ABC News; 2020. Coronavirus Fears for Kimberley as Two More Healthcare Workers Test Positive for COVID-19.https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-09/kimberley-coronavirus-fears-as-more-health-workers-positive/12137044 Published Accessed May 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley A.J., Evans C., Colton H. Roll-out of SARS-CoV-2 testing for healthcare workers at a large NHS foundation trust in the United Kingdom, March 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(14):1–4. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.14.2000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai X., Wang M., Qin C. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019) infection among health care workers and implications for prevention measures in a tertiary hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3(5) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancet The. COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395(10228):922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapolla P., Mingoli A., Lee R. Deaths from COVID-19 in healthcare workers in Italy – what can we learn? Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laschon E. ABC News; 2020. WA Coronavirus Community Transmission Begins as 17 New COVID-19 Cases Reported.https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-19/coronavirus-community-transmission-wa-as-17-new-cases/12072092 Published Accessed May 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- LaVela S., Goldstein B., Smith B., Weaver F.M. Working with symptoms of a respiratory infection: Staff who care for high-risk individuals. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2007;35(7):448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law P. South Western Times; 2020. Coronavirus Crisis: St John of God Subiaco Surgeon Tests Positive to COVID-19.https://www.swtimes.com.au/news/coronavirus/coronavirus-crisis-st-john-of-god-subiaco-surgeon-tests-positive-to-covid-19-ng-b881493324z Published Accessed May 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch L. Brisbane Times; 2020. Fears of Cairns Cluster After 5 Hospital Lab Workers Test Positive.https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/queensland/fears-for-cairns-cluster-after-5-hospital-lab-workers-test-positive-20200421-p54lpc.html Published Accessed May 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, C.R., Ananda-Rajah, M., Nicholls, M., Quigley, A.L., 2020. Current guidelines for respiratory protection of Australian health care workers against COVID-19 are not adequate and national reporting of health worker infections is required. Med. J. Aust. July. doi:Preprint. [DOI] [PubMed]

- MacIntyre C.R., Chughtai A.A., Zhang Y. Viral and bacterial upper respiratory tract infection in hospital health care workers over time and association with symptoms. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017;17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2649-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre C.R., Seale H., Yang P. Quantifying the risk of respiratory infection in healthcare workers performing high-risk procedures. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014;142(9):1802–1808. doi: 10.1017/S095026881300304X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mail Times. WA hospital worker contracts coronavirus. https://www.mailtimes.com.au/story/6729349/wa-hospital-worker-contracts-coronavirus/. Published 2020. Accessed May 25, 2020.

- Martin P. World Socialist; 2020. Nearly Half a Million Health Care Workers Worldwide Infected with Coronavirus.https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2020/06/04/coro-j04.html Web Site. Published Accessed June 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- May R.Le. 7 News; 2020. Infected Worker Sparks Aged Care Lockdown.https://7news.com.au/news/health/wa-premier-rejects-state-border-close-call-c-749114 Published Accessed May 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McCauley D. The Sydney Morning Herald; 2020. Doctors “Bullied” by Hospital Administration for Asking to Wear Masks Coronavirus.https://www.smh.com.au/national/doctors-bullied-by-hospital-administration-for-asking-to-wear-masks-20200703-p558v2.html Published Accessed July 8, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Medical board: Statistics. AHPRA & medical boards. https://www.medicalboard.gov.au/News/Statistics.aspx. Published 2020. Accessed May 25, 2020.

- Morawska L., Milton D.K. It is time to address airborne transmission of COVID-19. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020:1–23. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northern Territory Government. Coronavirus (COVID-19). https://coronavirus.nt.gov.au/updates. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- NSW Department of Health. COVID-19 (Coronavirus) statistics. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/news/Pages/20200411_00.aspx. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- NSW Department of Health. COVID-19: Updated advice on testing, 28 April 2020. Situation report. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Infectious/covid-19/Pages/case-definition.aspx. Published 2020. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- NSW Department of Health. Media releases from NSW health. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/news/pages/2020-nsw-health.aspx. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- NSW Government . NSW; 2020. NSW COVID-19 Cases Data. Data.https://data.nsw.gov.au/nsw-covid-19-data/cases Published Accessed June 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Olle E. 7 News; 2020. Ambulance Victoria Confirms Two Paramedics have Tested Positive to Coronavirus.https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/ambulance-victoria-confirms-two-paramedics-have-tested-positive-to-corona-virus-c-1151335 Published Accessed July 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Olle E. 7 News; 2020. Royal Adelaide Hospital Nurse Tests Positive to Coronavirus.https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/royal-adelaide-hospital-nurse-tests-positive-to-coronavirus-c-974689 Published Accessed June 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oran D.P., Topol E.J. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;(6) doi: 10.7326/m20-3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queensland Government. Queensland COVID-19 statistics. https://www.qld.gov.au/health/conditions/health-alerts/coronavirus-covid-19/current-status/statistics. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- Queensland Government. QLD department of health media releases. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/news-events/doh-media-releases. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P. Transmission of 2019-NCOV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(10):970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarpia J.L., Rivera D.N., Herrera V.L. Aerosol and surface transmission potential of SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.23.20039446. March:1-19https://doi.org/ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seo B. More than 120 doctors and staff quarantined, but worst to come. Australian financial review. https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/more-than-120-doctors-staff-quarantined-but-worst-yet-to-come-20200306-p547nu. Published 2020. Accessed June 12, 2020.

- Tang L.-H., Tang S., Chen X.-L. Avoiding health worker infection and containing the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: perspectives from the frontline in Wuhan. Int J Surg. 2020;79(April):120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasmanian Government Department of Health. TAS news releases. https://www.dhhs.tas.gov.au/news. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- Victoria State Government Health and Human Services. Victorian healthcare worker coronavirus (COVID -19) data. Latest News and Data. https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/victorian-healthcare-worker-covid-19-data. Published 2020. Accessed October 10, 2020.

- Victoria State Government. Media releases. https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/media-centre/mediareleases. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- Victoria State Government; Health and Human Services. Getting tested for coronavirus (COVID-19). https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/getting-tested-coronavirus-covid-19. Published 2020. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- Victoria State Government; Health and Human Services. Media hub - coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/media-hub-coronavirus-disease-covid-19. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widera E., Chang A., Chen H.L. Presenteeism: a public health hazard. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010;25(11):1244–1247. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1422-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock A. The Independent; 2020. Coronavirus: Fewer than One in 50 NHS Frontline Staff Forced to Stay at Home have been Tested.https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/coronavirus-nhs-staff-tests-stay-at-home-how-many-a9441251.html Published Accessed June 17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley S. 7 News; 2020. Healthcare Worker Among Victoria's New COVID Cases as More Schools Shut.https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/healthcare-worker-among-victorias-new-covid-cases-as-more-schools-shut-c-1138023 Published Accessed July 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley S. Sydney midwife at St George hospital tests positive for COVID-19. https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/sydney-midwife-at-st-george-hospital-tests-positive-for-covid-19-c-763398. Published 2020. Accessed May 25, 2020.

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2019. Coronavirus Disease. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO; 2020. Novel Coronavirus (2019-NCoV) 22 January 2020.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200122-sitrep-2-2019-ncov.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Writer S. Western Suburb Weekly; Perth Now: 2020. Healthcare Worker Returns Positive COVID-19 Test.https://www.perthnow.com.au/community-news/western-suburbs-weekly/healthcare-worker-returns-positive-covid-19-test-c-899969 Published Accessed May 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wynne R., Ferguson C. Rising coronavirus cases among Victorian health workers could threaten our pandemic response. Conversation. 2020 https://theconversation.com/rising-coronavirus-cases-among-victorian-health-workers-could-threaten-our-pandemic-response-142375 Published Accessed July 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan M., Qin Y., Xue X., Zhu S. Death from Covid-19 of 23 health care workers in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1056/nejmc2005696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Wang X., Zhou C. Analysis of the infection status of the health care workers in Wuhan during the COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa588. May:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]