Significance

Migration is increasingly presented as an adaptation solution to climate change. When populations move, they change their level of exposure and vulnerability to climate change impacts. We analyze how different border policies might affect people’s exposure and vulnerability. We propose a substantial methodological innovation by including explicit migration and remittance dynamics in one of the models typically used to compute climate change damages. We find that restrictive border policy can increase exposure and vulnerability, by trapping people in areas where they find themselves more exposed and vulnerable than where they would otherwise migrate.

Keywords: migration, climate change impacts, border policy, integrated assessment models, shared socioeconomic pathways

Abstract

Migration may be increasingly used as adaptation strategy to reduce populations’ exposure and vulnerability to climate change impacts. Conversely, either through lack of information about risks at destinations or as outcome of balancing those risks, people might move to locations where they are more exposed to climatic risk than at their origin locations. Climate damages, whose quantification informs understanding of societal exposure and vulnerability, are typically computed by integrated assessment models (IAMs). Yet migration is hardly included in commonly used IAMs. In this paper, we investigate how border policy, a key influence on international migration flows, affects exposure and vulnerability to climate change impacts. To this aim, we include international migration and remittance dynamics explicitly in a widely used IAM employing a gravity model and compare four scenarios of border policy. We then quantify effects of border policy on population distribution, income, exposure, and vulnerability and of CO2 emissions and temperature increase for the period 2015 to 2100 along five scenarios of future development and climate change. We find that most migrants tend to move to areas where they are less exposed and vulnerable than where they came from. Our results confirm that migration and remittances can positively contribute to climate change adaptation. Crucially, our findings imply that restrictive border policy can increase exposure and vulnerability, by trapping people in areas where they are more exposed and vulnerable than where they would otherwise migrate. These results suggest that the consequences of migration policy should play a greater part in deliberations about international climate policy.

Migration decisions are often multicausal and rarely due to environmental stress alone. Climate change may influence migration both directly and indirectly through various channels: economic, political, social, demographic, and environmental (1). Migration patterns can respond to extreme weather events (projected to increase in intensity in the future) and long-term climate variability or change [droughts, sea-level rise (2)]. Those changes might both enhance and reduce migration flows (3, 4).

Migration decisions at the individual or household level might not directly reflect such environmental changes for several reasons. First, migration may be increasingly used as an adaptation strategy to climate change (5, 6). For instance, remittances from earlier migrants may reduce incentives to move (7). In contrast, established migration networks may increase an individual’s propensity to move. Second, either through lack of information about risks at destinations or as the outcome of a balancing of risks, migrants might move to areas that are more or less exposed to climate change impacts than those where they came from (8, 9). Third, climate change is likely to lead to resource depletion in some of the most deprived areas, thereby trapping individuals who cannot afford to move (10, 11). Therefore, higher levels of climate change will likely reduce people’s ability to move on their own terms, inducing both an increasing number of people who are forced to move (displacement) and an increasing number of people who are forced to stay in their origin locations (12).

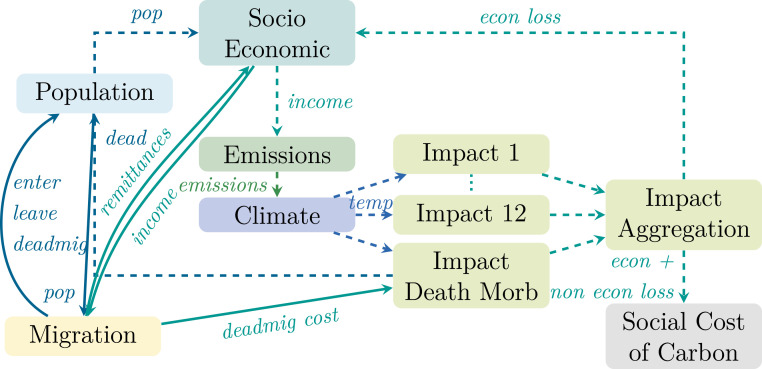

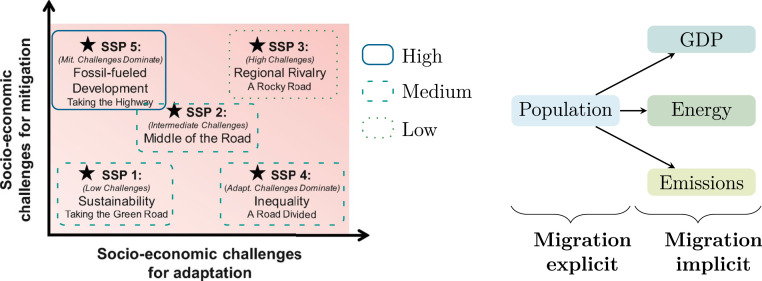

Climate change damages, whose quantification informs assessment of exposure and vulnerability, are typically endogenized in integrated assessment models (IAMs). IAMs couple a single climate model to one of the global economy, by representing greenhouse gas emissions as well as damages on the economy resulting from climate change. Some IAMs provide a representation of mitigation costs and impacts as a single economic metric through their monetary-equivalent value (e.g., Dynamic Integrated Climate-Economy [DICE]; Climate Framework for Uncertainty, Negotiation, and Distribution [FUND]; and Policy Analysis of the Greenhouse Effect [PAGE]; for an illustration of IAM structure, see Fig. 4). Such IAMs are used for cost–benefit analyses centered on maximizing welfare to identify optimal climate change policies; calculations of marginal effect of emissions on social welfare, also called the social cost of carbon (SCC); as well as sensitivity analyses aiming at weighing the relative importance of various climate change drivers, impacts, and policies. Both the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the National Academy of Sciences have called for improvements in IAMs’ damage functions (13, 14).

Fig. 4.

Including international migration dynamics in the FUND IAM. Dashed arrows refer to preexisting links between FUND components. We add the migration component (yellow) and link it to other components as described by the solid arrows. Blue arrows relate to population dynamics, while turquoise arrows illustrate income dynamics.

Migration is at this point hardly included in commonly used IAMs. For most models, migration is absent from the IAM itself and considered only implicitly, as part of required input population growth scenarios. The only IAM that includes it somewhat more explicitly in its damage function is FUND. Currently, displacement caused by sea-level rise is accounted for in FUND. However, its modeling includes arbitrary estimates of displacement costs, fixed destinations over time, and no economic adaptation such as remittances (15). Furthermore, recent efforts have been deployed to study climate–migration interactions using a variety of non-IAM models. Ref. 16 uses a dynamic spatial model to analyze effects of climate change on production, migration, and trade. They find that in a climate change context, migration restrictions have significant effects on welfare as well as on spatial inequities. Ref. 2 uses a similar model to quantify the economic costs of climate change-driven coastal flooding, inducing mainly internal moves. Ref. 17 uses an overlapping generations model in the continuous space and focuses on migration projections along climate change scenarios. Note that such models feature limited to no endogenization of the feedback of the economy on climate change in the form of greenhouse gas emissions.

Here, we focus on international, long-term migration dynamics in conjunction with exposure and vulnerability to climate change†. While the majority of migration, and in particular of climate-related migration, is expected to take place within countries (5), many severe political controversies taking place around migration both generally and in the context of climate change tend to focus on cross-border, long-distance migration. The past few years have seen several destination countries framing the future arrival of large swaths of international migrants as one of the main effects of climate change domestically (18). In this context, restrictive border policy is often framed as a measure to “mitigate” the effects of climate change. Yet a careful assessment of the consequences of such policies not only on host communities, but also on migrants and on home communities is of utmost importance to understand their appropriateness. How do border policies affect migrants and home and host communities’ exposure to climate change impacts?

In this paper, we provide a quantitative analysis of the effect of border policy—a key influence on international migration flows—on exposure and vulnerability to climate change impacts, for migrants and origin and host communities. This analysis contributes to the ongoing effort toward endogenizing population dynamics in IAMs and constitutes a directly usable approach for assessing national and global policy interactions. To this aim, we include migration explicitly and remittance dynamics in a widely used IAM; compare scenarios of border policy; and quantify effects on population distribution, income, exposure and vulnerability, emissions, and overall temperature increase. In line with the literature, we show that border policy has a clear effect on net migration in all regions and that when allowing movement it is a key source of economic welfare for less developed regions through remittances. Furthermore, we find that border policy has little effect on global emissions and virtually none on temperature increase, but does influence region-specific emissions both through changed population size and through income transfers in the form of remittances. Crucially, we show that most migrants from developing regions tend to move to areas where they are less exposed than they would have been by remaining in place. This happens not because they intentionally move into less dangerous areas—our model does not capture detailed reasons of migrants’ intentions—but because wealthier regions also happen to be less exposed. Our results produce three major takeaways. First, migration and remittances can make a positive contribution to adaptation to climate change impacts. Second, restrictive border policy can increase exposure and vulnerability to climate change impacts by trapping people in areas that are more exposed than where they would otherwise migrate. Third, reducing inequality between countries would also decrease the need and benefit to use international migration as an adaptation solution; hence considerations of unequal levels of development across regions are crucial to understanding international migration flows and to a relevant assessment of climate change damages.

Results

Effect of Border Policy on Population Distribution.

Migration flows obtained with our model reproduce the main known international patterns well, with most developed regions (e.g., United States and Western Europe) being net destination regions and developing regions (e.g., Sub-Saharan Africa and Central America) being net origin regions over this century. Overall, migration flows modify each region’s population size by up to 0.9%. This is a significant amount—for comparison, migrant flows into the United States in 2010 constituted 0.7% of the American population. For information, we also provide results without climate change effect—that is, without climate change damages affecting the economy (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). We find that climate change affects migration numbers only marginally, increasing worldwide international migration by 0.3 to 1.1% in 2100 compared to no climate change at the same period, depending on the border policy and development and climate scenario considered. For our medium scenario (Shared Socioeconomic Pathway [SSP]2-Representative Concentration Pathway [RCP]4.5) with current border policy, this corresponds to an increase in global migration flows in 2100 of about 75,000 people.

Furthermore, we find that border policy itself has a clear quantitative effect on net migration in all regions. In most regions, closing borders between Global North and Global South has similar effects to closing all borders, which signals that most migration for those regions has taken place between Global North and Global South. Yet for some (e.g., Central and Eastern Europe and the Middle East), most migration happens within either Global North or Global South. Note that for the Small Island States and South America, border policy also has a qualitative effect: Closing borders between North and South makes them become net destination regions. Conversely, Canada and Japan and South Korea become net origin regions, as their geographic remoteness makes them a rare destination choice for most northern regions (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

Effect of Border Policy on Income per Capita (after Remittances).

Our model endogenously calculates the share of income that a migrant sends back to the origin region as remittances (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). In 2015, remittance shares range from from 8 to 110%, depending on the migration corridor; note that remittance shares are higher than 100% (e.g., in corridors ending in South Asia) when immigrants have a higher income than the (low) average per capita income at destination. Yet for all regions and all development–climate scenarios, the share of income sent as remittance decreases over time as regions sustain economic convergence. Scenarios presenting a stronger convergence between regions (SSP1 and SSP5) provide the strongest decrease; conversely the scenarios presenting weaker convergence (SSP3 and SSP4) witness the weakest decrease.

Our model also allows us to obtain explicit remittance flows between regions (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Unsurprisingly, more remittances are exchanged as borders are more open‡. Most regions that are destinations for migration are net sending remittances regions, and vice versa. An interesting exception is Canada, which when borders are closed between Global North and South becomes both a net origin region for migrants and a net sending region for remittances, as its emigrants move to areas that are not much richer and/or present unattractive remittance sending possibilities, while its immigrants send back to their home regions more substantial remittances. This exception holds for all climate change and development scenarios, implying that border policy plays a more important role than either economic development or climate change in our model for Canada.

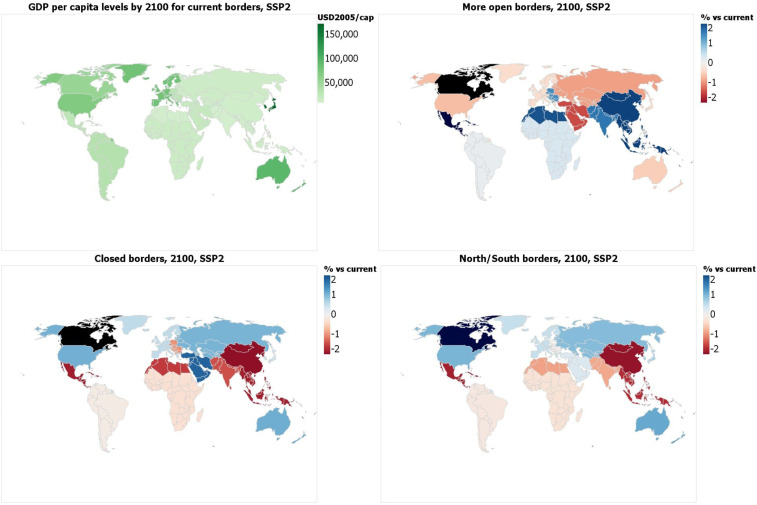

We further look at the effect of border policy on income, once remittances have been transferred between regions. Fig. 1 (Top Left) shows region-specific per capita income levels by the end of the century if borders stay as easy or difficult to cross as they are currently. We then compare results with the three other border policy scenarios to this baseline of current borders. Our results are consistent with the literature on the more general effect of border policy on income in origin and destination (19–22), regardless of the climate change context. In particular, we find that opening borders more would strongly benefit Central America, the Small Island States, and Southeast Asia—increasing their gross domestic product (GDP) per capita level by up to 2.6, 2.4, and 2.1%—as these regions would receive more remittances from wealthier regions than they send to poorer regions (Fig. 1, Top Right). Conversely, China as well as those regions would be most hit by closing all borders, with a decrease in per capita income of 2.0 and 1.8%, respectively (Fig. 1, Bottom Left). Closing borders between North and South would hurt the Small Island States and China in particular, reducing their GDP per capita by 2.0 and 1.9%; indeed those regions, among the richest in the Global South by the end of the century, become sources of more remittances sent to other southern regions (Fig. 1, Bottom Right).

Fig. 1.

Effect of border policies on per capita income after remittances. Shown are results in the 16 FUND regions over the period 2015 to 2100 for SSP2 (middle of the road) coupled to RCP4.5. (Top Left) Per capita income levels for current borders. (Top Right) Relative change for more open borders compared to current borders. (Bottom Left) Relative change for closed borders compared to current borders. (Bottom Right) Relative change for borders closed between Global North and Global South compared to current borders.

Effect of Border Policy on Exposure and Vulnerability.

FUND explicitly features different types of impacts from climate change on the economy (15). We use the damages to GDP ratio in each region as a measure of exposure and vulnerability to climate change impacts. We find that this ratio tends to be higher in developing regions, regardless of the scenarios of future development and of mitigation policy considered (SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

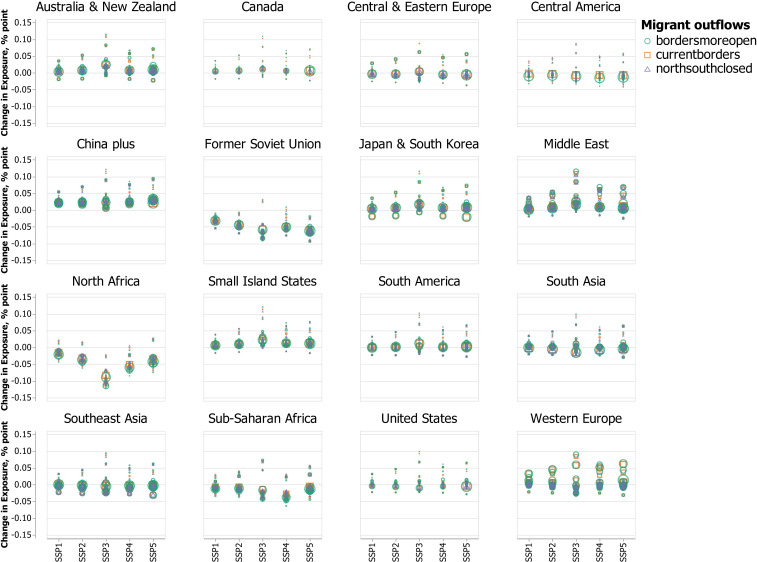

As our key contribution, we analyze in which direction and to what extent migrants change their level of exposure and vulnerability when they move from one region to another. Results are displayed in Fig. 2. For each region, we highlight whether migrants who leave that region tend to move to an area where they find themselves more exposed and vulnerable (positive change in exposure and vulnerability) or less exposed and vulnerable (negative change) than in their home region. We present results for 2100, for all five SSP-RCP combinations and for the three scenarios of border policy that do allow migrants to move.

Fig. 2.

Effect of border policies on migrants’ exposure and vulnerability: change in damages/GDP ratio—quantifying exposure and vulnerability—in percentage point, experienced by migrants leaving each of the 16 FUND regions. Shown are results for 2100, for all five SSP narratives coupled to relevant RCP. Each symbol represents a migrant flow from the region considered toward one of the other 15 regions, for a given border policy. Symbol sizes are proportional to migrant flow sizes. Symbol shapes and colors represent border policies; the closed borders scenario, incurring no migrants, is not featured.

Crucially, we find that most migrants—in particular from developing countries—tend to move to areas where they are less exposed and vulnerable than where they came from. This happens not because they intentionally move into less dangerous areas (such intentions are not captured by this model), but because destination regions—wealthier—also happen to be less exposed and vulnerable. This result complements previous descriptive findings of correlative evidence between climate vulnerability and migration based on past data (8). We show that differences in exposure and vulnerability levels across regions can be substantial, up to 10 percentage points of GDP for SSP3. Therefore, closing borders would increase the number of people more severely exposed and vulnerable to climate change impacts, by trapping them in areas where they are more exposed and vulnerable than where they would end up if they had the possibility to move more freely. On the other hand, reducing inequality between countries would also decrease the need and benefit to use international migration as an adaptation solution; hence considerations of unequal levels of development across regions are crucial to understanding international migration flows in conjunction with climate change damages.

Note that this finding omits two relevant effects of migration. First, migration changes the demographic profiles of both origin and destination populations, as international migrants tend to be young, working-age adults and healthier than the destination population (1, 5). Thus, they are potentially less at risk from certain impacts of climate change (e.g., on health), which reduces vulnerability further at destination, while increasing it at origin. Second, exposure and vulnerability are spatially differentiated within a given region. Here, our result is based on regional average exposure and vulnerability levels in origin and destination regions. Yet migrants—when allowed—might move from areas where they are less exposed and vulnerable than the origin regional average into areas (e.g., urban informal settlements, coastal megacities) where they are more exposed and vulnerable than the destination regional average (1). In such a case, migrating would potentially increase their exposure and vulnerability to climate change impacts. However, while some data are available both on migrants’ specific locations and on specific exposure and vulnerability levels within a region for some destination regions (the United States in particular), to our knowledge similar data are not available on both aspects in origin regions. We acknowledge that these are limitations to our findings and consequently are measured in our conclusions.

Effect of Border Policy on Emissions and Global Temperature Increase.

Integrating migration and remittance dynamics in an IAM enables us to look at the effect of border policy and resulting migration and remittance flows on greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed, as discussed above migration flows do modify each region’s population size by up to 0.9%. Furthermore, we assume that migrants, once in the destination region, instantaneously adopt the local consumption behavior and average carbon footprint per unit of income (we assume their income per capita to be the larger of origin and mean of origin and destination income; Materials and Methods). Although consumption behaviors of migrants might differ from host communities for activities with particular cultural components (e.g., cooking), the literature suggests that income levels are the strongest determinant of individuals’ carbon footprints (23, 24); thus we consider our assumption reasonable.

Population changes and income transfers in the form of remittances as a result of migration do generate modified regional emissions levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). In particular, we find that opening borders more would increase emissions in most destination regions through increased population size and decrease emissions in most origin regions as income level increases through remittances do not compensate population decreases. The opposite happens when closing borders.

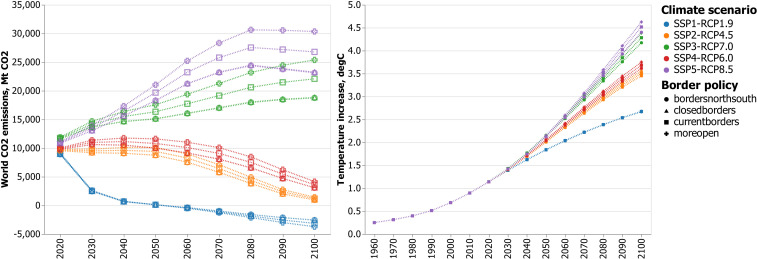

However, we find that such differences in emissions at the regional level have a moderate effect on global emissions and hence almost no effect on overall temperature change over the 21st century. Fig. 3 illustrates global emissions and overall temperature increase for our four scenarios of border policy, for each of the five SSP-RCP combinations. While the development/climate scenarios clearly lead to different emissions and temperature outcomes, border policy affects global emissions, but barely overall temperature change. Furthermore, scenarios for closing all borders or closing borders only between Global North and Global South are almost perfectly superposed and indistinguishable.

Fig. 3.

Effect of border policies on world emissions in megatons (Left) and global average temperature increase in degrees Celsius (Right). Colors illustrate all five SSP narratives coupled to relevant RCP. Symbol shapes represent border policies.

Conclusion

In this paper, we propose a substantial methodological innovation by including explicit migration and remittance dynamics in a widely used IAM. In doing so, we make the migration effect on and response to climate change impacts explicit, focusing on the income channel, key for international migration. Furthermore, we avoid double counting of migration by using versions of socioeconomic input and technological input scenarios without migration. The methodological benefit of this analysis is thus twofold. First, we contribute to the ongoing effort toward endogenizing population dynamics in IAMs. Second, we propose a directly usable approach for assessing climate and migration policy interactions.

Furthermore, this study provides a quantitative analysis of the effect of border policy on exposure and vulnerability to climate change impacts, for migrants and origin and host communities. We find that exposure and vulnerability tend to be higher in developing regions. Crucially, we show that over the 21st century, most migrants from developing regions tend to move to areas where they are less exposed and vulnerable than where they came from. This result stands for all commonly explored scenarios of future development and levels of climate change. Therefore, aligned with qualitative assessments (6), our results suggest that restrictive border policy is likely to increase exposure and vulnerability to climate change impacts, by trapping people in areas where they find themselves more exposed and vulnerable than where they would otherwise migrate.

Moreover, this analysis confirms the role of migration and remittances as a positive contribution to adaptation to climate change impacts. By explicitly representing both bilateral migration and remittance flows between regions, we show that opening borders provides an important source of income for origin, often more exposed regions, which could be used for reducing vulnerability to climate change impacts in those regions. In particular, we find that opening borders more would strongly benefit Central America, the Small Island States, and Southeast Asia which would receive more remittances. Conversely, those regions as well as China would be most hit by closing all borders. Closing borders between North and South would especially hurt the Small Island States and China, making them a source of more remittances sent to other southern regions.

Finally, this study quantifies the migration effect on emissions and climate change itself. We show that border policy influences region-specific emissions more through changed population size than through income transfers in the form of remittances, but has little effect on global emissions and virtually none on overall temperature increase. This result stands regardless of the scenario of future development or of climate change considered.

These findings suggest direct policy-relevant implications. First, deliberation over migration policy could make an important contribution to international climate policy discussions, as part of larger efforts to meet the sustainable development goals and as encouraged by the 2018 United Nations (UN) Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (6). Second, considerations of unequal levels of development across regions are crucial to understanding international migration flows in conjunction with climate change damages. Indeed, reducing inequality between countries would also decrease the need and benefit to use international migration as an adaptation solution to climate change impacts.

Materials and Methods

Migration and Remittance Flows: A Gravity Model.

In a first step, we model migration dynamics. We focus on international, long-term migration. Major influences on such type of migration tend to revolve around three categories: economic opportunities (e.g., possibility of earning higher income, of sending remittances back home); proximity, whether geographic, political (e.g., shared colonial history), or cultural (e.g., common official language); and migration costs, among which border policy is a key factor. Gravity models (4, 25, 26) bring these push-and-pull factors into one framework.

Here we employ such a model and express bilateral migrant flows as a function of population sizes and per capita incomes levels of origin and destination regions, as well as geodesic distances between regions’ centers of population . We also include a set of bilateral characteristics of the origin/destination pair indicating the share of each migrant’s income sent as remittance (as defined in Eq. 3); the cost of sending said remittances, ; whether the two regions share a common official language, ; and an implicit representation of border policy between the two regions, (see Border Policy Scenarios). Our resulting gravity model is encapsulated in Eq. 1:

| [1] |

The total number of migrants leaving a given country at time is given by , while the number of immigrants is given by .

To model how many migrants send remittances, we compute a state variable, , that keeps count of how many migrants from one region are present in another region at a given time (Eq. 2). This bilateral “stock” of migrants is initiated as described below, accumulates over time with new arrivals , and decreases over time once migrants pass away. This duration is computed as life expectancy at birth, , in the destination region minus median age of migrants at time of migration, . We derive remittance flows by assuming that only first-generation migrants send money back to their origin region in the form of remittances, for the duration of their life. This assumption coarsely illustrates the few empirical findings of the migration literature focusing on second-generation remittances, suggesting that second-generation migrants are significantly less likely to send remittances to their parents and send smaller amounts (27):

| [2] |

In terms of amount of money sent as remittances, we assume that each migrant sends a corridor-specific share of income to the origin region, for a corridor-specific cost, . While we take as exogenous (see Calibration of Other Migration Parameters), we model as a function of per capita income levels of origin and destination regions and of the corridor-specific cost. Our resulting model describing the share of a migrant’s income sent as remittance is featured in Eq. 3. Corridor-specific residuals, , are then used in our gravity model featured in Eq. 1:

| [3] |

Furthermore, we assume that a migrant’s income at destination is the larger amount of two quantities: mean of origin and destination per capita incomes and origin per capita income. This assumption illustrates the effect of cases where immigrants from lower-income countries are not able to reach average income levels at destination and cases where immigrants from higher-income countries (“expatriates”) earn significantly higher incomes than the average income at destination. Note that we assume that immigration does not modify destination income per capita levels (28). Total net flows into a given region are computed as the difference between remittances received from all emigrants’ destinations and remittances sent by all immigrants to their origin , again notwithstanding corridor-specific costs of sending remittances (Eq. 4):

| [4] |

Finally, we consider a corridor-specific risk of dying while attempting to migrate, . To compare such migrants’ deaths to other damages from climate change, we use the value of statistical life (VSL) (29).§ Here, we use time- and region-specific VSL endogenously computed by the IAM (Eq. 5). We use the migrant value for VSL, following our assumption of migrant income at destination, as a migrant heading for a higher income would have a greater willingness to pay for safety than if the migrant stayed in the country of origin¶ :

| [5] |

Note that we account for endogeneity issues in the following ways. First, there is potential reverse causality between remittances and migration: Remittances are not only the result of migrant stocks, they also drive migration decision. We account for both effects in our combined gravity and remittance model: Remittances increase with migrant numbers, but decrease when differences in income between origin and destination are reduced. Conversely, migration increases with the proportion of income sent as remittance, but decreases when differences in income between origin and destination are reduced, e.g., through remittances (see ref. 7 for an empirical example in rural Mexico). Second, endogeneity can arise between remittances and economic development: Remittance amounts are driven by the level of development both at destination and at origin, but also affect levels of development at origin (recipient) countries. We also take this effect into account by displaying GDP levels after remittances have been transferred (Fig. 1). Third, there is potential reverse causality between migration and economic development: Migration is driven by absolute and relative levels of economic development, but also affects development levels at destination. We account for that effect coarsely, by assuming that immigration does not modify destination income per capita levels and hence overall increases income levels (see above). This limitation is an inevitable consequence of the rather stylized fundamental structure of IAMs.

Modeling: Including Migration Dynamics in an IAM.

In a second step, we include our migration and remittances dynamics model in an existing IAM. We choose FUND (15), as it presents useful features for this project: some regional disaggregation (16 regions, 2 of them representing one country each: United States and Canada; SI Appendix, Table S1) and a sectoral quantification of damages (12 impact sectors). FUND takes exogenous scenarios of key economic variables as inputs (population growth, income per capita growth, growths of the energy intensity of the economy and of the carbon intensity of energy) and then perturbs these with estimates of the cost of climate policy and the impacts of climate change. The 12 climate change impacts are monetized and include those on agriculture, forestry, human health, energy consumption, water resources, and unmanaged ecosystems, as well as those arising from sea-level rise and storms. FUND has a constant income elasticity of damages, yet each impact sector has a different functional form and is calculated separately for each of the 16 regions# (33). Note that while FUND requires an exogenous input scenario of GDP growth, part of the climate change damages in one period reduces the production of the next period instead of reducing only the consumption in the present period.

We use a modular approach: This IAM being constructed as an ensemble of components∥ , we create a new migration component and plug it into FUND (Fig. 4). Importantly, migration and climate change impacts interact only indirectly through the income channel: Migration changes population distribution and generates income transfers between regions, which modifies each region’s emissions profile and damages. Conversely, climate change generates region-specific damages and hence modifies relative income levels—a driver of our migration dynamics model. Hence, in our model income is determined by region-specific endogenous growth, climate change damages, and remittances.

Note that while FUND runs for the period 1950 to 3000 in yearly time steps, we make the migration dynamics explicit starting in 2015 and present results for the period 2015 to 2100.

Gravity Estimation.

We estimate our gravity equation by ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression (Eq. 6). For the estimation, it is assumed that is constant over time and calibrated so that (we will later vary this assumption by using different scenarios of border policy; see Border Policy Scenarios):

| [6] |

We perform the estimation at the country level. Bilateral migrant flows data are derived from 1990 to 2015 stock estimates from the World Bank, available for 5-y periods, using two methods of derivation: ref. 34, as collected in ref. 35, and ref. 36.†† Data on independent variables are available from the World Bank; for a detailed description of data on remittance characteristics, see Calibration of Other Migration Parameters. Note that migration time series are nonstationary by nature. To ensure that we are capturing underlying trends in the data, we use year fixed effects in the estimation. From our gravity model specification, we also capture trends related to convergence or divergence in economic development levels, as well as rough demographic trends (changes in population sizes). Yet we do not explicitly capture trends linked to geopolitical events. This limits our ability to fully capture nonstationarity.

The resulting estimation is presented in Table 1. Results imply that migration flows between two countries increase with origin population size and with the existence of a common language and decrease with distance between countries, as suggested in other studies using similar models (e.g., ref. 25). Migration flows also tend to increase with destination population size and per capita GDP. The effects of bilateral characteristics (distance, remittances shares and costs, common official language) are as we would expect. Unsurprisingly, remittance costs reduce migration—yet the effect is not significant. Conversely, the variable measuring remittances as share of income has a positive effect on migration, hinting at the effects of migration networks on the persistence of migration flows: People tend to move to areas where strong remittance traditions with their home countries exist. Alternatively, if the migration is a collective household decision, this positive effect might reflect the desirability to the household as a whole of the extra income. We provide a first robustness check by estimating parameters using data from ref. 36 (Table 1, column 2) and find that our projections are virtually not affected by the data source.

Table 1.

Results from OLS regression on country-level bilateral migration flows

| Migration flows | ||

| Column 1, | Column 2, | |

| dataset 1 (34) | dataset 2 (36) | |

| Origin population | 0.689*** | 0.578*** |

| (0.040) | (0.031) | |

| Destination population | 0.686*** | 0.606*** |

| (0.042) | (0.042) | |

| Origin per cap GDP | 0.417*** | 0.100* |

| (0.060) | (0.045) | |

| Destination per cap GDP | 0.830*** | 0.784*** |

| (0.070) | (0.066) | |

| Distance between locations | −1.297*** | −1.045*** |

| (0.063) | (0.062) | |

| Residuals from share of | 0.011* | 0.004 |

| income sent as remittances | (0.005) | (0.007) |

| Cost of sending remittances | −9.670 | −15.363 |

| (15.655) | (15.806) | |

| Common official language | 1.743*** | 1.464*** |

| (0.133) | (0.120) | |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| Estimator | OLS | OLS |

| 73,397 | 91,163 | |

| 0.479 | 0.412 | |

*P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001. Specifications are with year fixed effects (columns 1 and 2). Estimates in column 1 are obtained based on data from refs. 34 and 35, while estimates in column 2 are obtained based on data from ref. 36. Standard errors clustered at the origin and destination levels are in parentheses.

Note that including origin and destination fixed effects in our estimation would imply that we are considering effects that are inferred from the deviations of migration flows from origin- and destination-specific long-run equilibria and as such can be thought of as summarizing short- to medium-run elasticities. The effects on changes in the long-run equilibria, on the other hand, are factored into the parameter estimates of the model without these country fixed effects. For that reason we consider the model with only year fixed effects to be the more appropriate for the projection exercise. In addition, projecting country fixed effects would lead to flow differences across countries remaining constant in the long run, hiding potential long-term effects of our socioeconomic covariates. For information, we provide estimations with country fixed effects on both datasets in SI Appendix, Table S2.

We provide further robustness checks in SI Appendix. First, we use region-level fixed effects (SI Appendix, Table S3). We find that the magnitude of coefficients somewhat changes, but neither their sign nor their significance. We do not find the use of regional fixed effects appropriate here, as such a specification would underestimate the effect of worldwide economic convergence—including between regions—featured in some of our scenarios by the end of the century, on migration flows. Second, we perform the estimation separately on low-income and non–low-income origin countries to determine whether migration trends are biased by low-income countries in a way that would not be relevant anymore once those countries reach higher levels of development over this century (SI Appendix, Table S4). We find that coefficients are relatively similar using both origin country groups. Third, we constrain the origin and destination income per capita terms to have the same coefficient with opposite signs, as in ref. 17‡‡(SI Appendix, Table S5). We find that the overall fit is not as good, which suggests that origin and destination income terms per capita affect migration to different extents, not only in different directions. Fourth, we include the effect of income in other countries than the origin and destination countries considered, also as in ref. 17 (SI Appendix, Table S6). We find that it has little effect on other coefficients. Fifth, we add a squared term on origin income per capita, to test whether its effect on migration flows changes direction above a certain income level (SI Appendix, Table S7). We find that it does not, as the squared-term coefficient is positive. Sixth, we include regional exposure and vulnerability levels in our gravity model (SI Appendix, Table S8). We find no robust effect of origin exposure level on migration flows and some positive effect of destination exposure: For the estimation period (1990 to 2015), migrants tended to move to areas that were among the more exposed to the limited impacts from climate change witnessed during this period. This suggests some spurious correlation between exposure and some omitted variable for this time period.

We then use the estimated coefficients of Table 1, column 1 in our migration model at the regional level. Remittance parameters and are transposed from country to region level as described in the Migration and Remittance Flows: A Gravity Model and the Calibration of Other Migration Parameters, respectively. Distances between regions are calculated as Haversine distances between centers of population of regions, computed as arithmetic means of coordinates of a region’s countries’ capitals weighted by 2010 country-level population. The presence of a common official language between two regions becomes a coefficient between 0 and 1, weighting all dummies for country pairs of the two regions with migration flows between the regions in the period 2010 to 2015 from ref. 34.

Finally, to realistically reflect each migration corridor’s specificity, we incorporate pair-specific residuals and time fixed effects of the last periods (one time fixed effect per period) from Eq. 6 in our migration model. More precisely, we add said residuals averaged over the last three 5-y periods (2000 to 2015) to our gravity model (Eq. 7) (such residuals are plotted in SI Appendix, Fig. S1):

| [7] |

Most corridors present residuals that are relatively constant over time, but some do vary significantly. We provide a robustness check in SI Appendix, Figs. S9 and S10 by performing a sensitivity analysis using only residuals of the last 5-y period (2010 to 2015). Results stay qualitatively similar.

Remittance Share Estimation.

We also estimate our remittance share equation by OLS regression (Eq. 8). Our parameter is defined as the share of income that a migrant sends as remittance, which in theory can vary both in absolute and in relative terms with income levels at origin and destination countries. Hence we estimate both and for robustness purposes:

| [8] |

We perform the estimation at the country level. The share of income sent as remittance is computed as follows: , with as in Eq. 4. For that purpose, we use bilateral remittance matrices available from the World Bank. Those are estimates of amounts in dollars sent between countries as remittances in a given year; they are estimated by the World Bank using migrant stocks as well as host and origin country incomes. We also use data on bilateral estimates of migrant stocks from the World Bank and on per capita income also from the World Bank. We use the last year for which all three datasets are available, which is 2017. For independent variables, we use data on income per capita from the World Bank, as well as data on the cost of sending remittances (expressed in percentage of amount sent) available from the World Bank’s database Remittance Prices Worldwide (39), all for the year 2017.

The resulting estimation is presented in Table 2. Results suggest that the proportion of a migrant’s income sent as remittance increases with the gap in per capita GDP between origin and destination as represented by the income ratios (see columns 2 and 4) and decreases with destination per capita GDP. High remittance costs tend to take place in corridors sending high shares of remittances (columns 1 and 2), likely the most profitable corridors for intermediaries harvesting these costs. Yet, unsurprisingly, higher remittance costs reduce remittance shares (columns 3 and 4) although this effect is not significant. Finally, the specification in provides a better fit, and hence we use it for our remittance model.

Table 2.

Estimation of remittances sent as share of migrant’s income

| Remittance share | ln (remittance share) | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Origin per cap GDP | −0.020** | −0.241** | ||

| (0.006) | (0.081) | |||

| Destination per | 0.001 | −0.019* | −0.362*** | −0.603*** |

| cap GDP | (0.004) | (0.009) | (0.031) | (0.090) |

| Ratio of per cap GDP | 0.020** | 0.241** | ||

| (0.006) | (0.081) | |||

| Cost of sending | 1.276* | 1.276* | −5.953 | −5.953 |

| remittances | (0.616) | (0.616) | (3.642) | (3.642) |

| Estimator | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS |

| 34,225 | 34,225 | 10,442 | 10,442 | |

| 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.133 | 0.133 | |

*P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001. Shown are results from OLS regression of remittance shares (columns 1 and 2) and log remittance shares (columns 3 and 4). Dependent variables are regressed on income per capita at destination and cost of sending remittances (columns 1 to 4), as well as income per capita at origin (columns 1 and 3) and ratios of destination to origin incomes (columns 2 and 4). Standard errors are clustered at the origin and destination levels.

We then use the estimated coefficients of Table 2, column 3 in our remittance model at the regional level. Remittance parameter is transposed from country to region level as described below. Residuals , used both in our remittance and in our gravity models (Eqs 1 and 3), are aggregated at the region level as described in SI Appendix.

Calibration of Other Migration Parameters.

Other remittance parameters are calibrated as follows. First, duration of migrants’ stay in the destination region is computed as the difference between life expectancy in the destination region and age of migrants at time of migration , both calibrated using SSP projections available at the country level. We assume constant parameters after 2100 (note that here we show only results for 2015 to 2100, so this assumption does not affect our results). For both parameters, we transpose from country to region level by weighting countries within each region by 2015 population size, using data from the Wittgenstein Center (40). As our migration dynamics model starts only in 2015, we also include an initial stock of migrants for that year. For that purpose, we use data on bilateral migrant stocks from the World Bank for 2017, the closest available year, and assign an age distribution built as the average of two distributions: the age distribution of migrants at time of migration in the period 2015 to 2020 and the age distribution of the overall destination population in the same period, both sourced from the SSP population projections.

Second, we estimate the share of a migrant’s income sent as remittances as described above. We also assume that the cost of sending remittances is constant over time and across the SSP narrative, but specific to the origin/destination pair. We calibrate this parameter using data on the cost of sending remittances (expressed in percentage of amount sent) available from the World Bank’s database Remittance Prices Worldwide (39) for the year 2017. We transpose it from country to region level by weighting migration corridors within each region by remittance flows. Remittance cost values range from 2 to 17% of the amount sent as remittance, depending on the corridor.

Finally, the risk of dying while attempting to migrate is also assumed constant over time and across the SSP narrative, but specific to the origin/destination pair. We calculate this risk as the ratio of missing migrants to the migrant flows on that journey. We calibrate this parameter using data on missing migrants for the period 2014 to 2018 from the International Organization for Migration, as well as data on migration flows between regions in the period 2010 to 2015 from ref. 34.

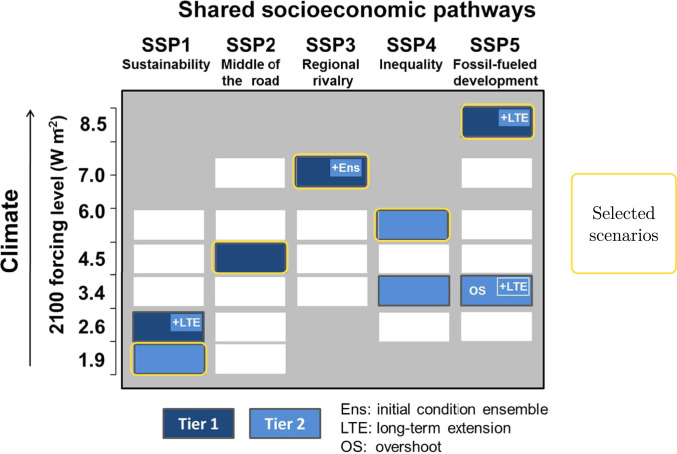

Input Scenarios: The SSPs without Migration.

FUND requires input scenarios of population, economic, energy, and carbon intensity growth. While default scenarios in FUND are based on the Special Report on Emissions Scenarios developed for the IPCC Special Report on Emissions Scenarios published in 2000, we use the more recently developed SSPs. The SSPs provide quantified projections of, among other indicators, population, GDP, final energy consumption, and greenhouse gas emissions along five narratives of future world development.

However, those SSP narratives include built-in assumptions on international migration (41), explicit only in population projections (42) (Fig. 5). Thus, using the original SSP quantifications as input to our migration dynamics model coupled to FUND would lead us to count migration twice: once in the input scenarios and once in the migration model itself.

Fig. 5.

The five narratives of the SSPs and their embedded assumptions on international migration. (Left) Reprinted from ref. 41, with permission from Elsevier. (Right) Data from ref. 42.

To avoid double counting of migration, we use versions of those scenarios without migration, which we developed in a previous project.§§ We proceeded as follows: First, population projections for zero migration were developed by Samir KC¶¶ using a demographic model of population dynamics. Second, we developed GDP projections for zero migration, using a similar gravity model with remittances to trace the migration effect on GDP. Third, we derived projections of final energy consumption and emissions for zero migration by assuming, for a given SSP narrative, that migration dynamics do not affect the energy consumption, respectively emissions path along GDP per capita levels. Note that for the energy consumption and emissions projections, we select relevant combinations of SSPs with climate scenarios, the Representative Concentration Pathways, among the ones selected for the upcoming IPCC Assessment Report (Fig. 6): SSP1-RCP1.9, SSP2-RCP4.5, SSP3-RCP7.0, SSP4-RCP6.0, and SSP5-RCP8.5.

Fig. 6.

Matrix of relevant combinations of development scenarios (SSP) and climate scenarios (RCP). Combinations shaded in blue are selected for the upcoming IPCC Assessment Report. Combinations also outlined in yellow are the ones used in this study. Reprinted from ref. 45, which is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Source for Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) data: ref. 46.

Furthermore, to project consistent mitigation costs, we use carbon price projections corresponding to the respective SSP-RCP combinations selected. These projections are computed using the process-based IAMs described in ref. 45. They feature narrative-specific global carbon prices. We illustrate those carbon price projections in SI Appendix, Fig. S2.

Finally, as FUND runs for the period 1950 to 3000 in yearly time steps while our SSP projections are available for the period 2015 to 2100 in 5-y time steps, we extend the projections as described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Assumptions used to extend SSP-based input scenarios to a FUND-compatible time frame

| Population | GDP per | Energy intensity of | Carbon intensity of | Carbon | |

| Period | growth | capita growth | GDP growth | energy growth | price |

| 2015 to 2100 | Linearize from 5-year periods to yearly values | ||||

| 1950 to 2015 | UN World Population | World Bank WDI (48) when | Default FUND | 1990 to 2015: CMIP6 data (46) | 0 |

| Prospects 2019 (47) | available, otherwise default | scenario (49) | 1950 to 1990: FUND | ||

| FUND scenario (49) | scenario (49) | ||||

| 2100 to 2300 | Linear decline to | Linear decline reaching 0 | Fixed at 2090 to 2100 rate if in 2100, | 0 | |

| 0 in 2200, then constant | otherwise linear decline reaching 0 | ||||

| 2300 to 3000 | Steady state: growth rates = 0 | ||||

WDI, World Development Indicators.

Border Policy Scenarios.

In a final step, we consider various scenarios for border policy. The use of scenarios for this key parameter appears justified by the highly perilous character of border policy prediction over such a timescale. Note that border policies are generally effective at controlling border crossings at their targeted locations, yet can lead to unintended effects on population movement that can limit their effectiveness. The DEMIG## project identified four types of such effects, namely spatial substitution where migration takes place through other routes or other destinations altogether, categorical substitution through other legal or illegal channels, intertemporal substitution precipitating migration in expectation of future stricter policies, and reverse flow substitution through the interruption of return migration encouraging permanent moves (50). The scenarios we use here, highly stylized, are not meant to provide realistic descriptions of actual border enforcement on the ground, but rather to capture the plausible magnitude of border policy effects on various outcomes.

We define four different scenarios for border policy and illustrate then by varying values for in our gravity equation (Eq. 1). First, we use as baseline a scenario keeping current borders as easy or difficult to migrate through as they are today. Second, we consider a scenario where borders are closed between all regions and hence where no migration is possible. Third, we look at a scenario where borders are more open than today, allowing doubling of migration flows. Fourth, we analyze a scenario for which borders are as open as today within the Global North and the Global South, but closed between. The corresponding values for in Eq. 1 are as follows:

-

•

Current borders:

-

•

Closed borders between all regions:

-

•

More open borders:

-

•

Borders open within Global North and Global South, closed between (see SI Appendix, Table S1 for a description of Global North and South):

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David Anthoff, Joel Cohen, Johannes Emmerling, Brian Jones, Robert McLeman, Aurélie Méjean, Stéphane Zuber, and participants of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists and European Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 2020 conferences for helpful feedback on earlier stages of this analysis. We also thank Guy Abel, Matthew Gidden, and Samir KC for data, as well as David Anthoff, Frank Errickson, Cora Kingdon, and Lisa Rennels for support with the FUND model.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

†A recent review of the literature on climate-related migration emphasizes that the development of projections of climate-related international migration is an important area for future research (3).

‡Changes in remittance flows can also occur without border policy playing a role. To disentangle the effects of such changes from those of border policy, we perform runs of our model without remittances (SI Appendix, Figs. S14–S18). In our model, this means that GDP per capita levels are not affected by migration, only GDP levels are. Thus, migration flows are little affected by a shutdown of remittances. Our central result on the change in exposure and vulnerability undergone by migrants when they move is accentuated, which highlights the crucial role of remittances in decreasing local exposure and vulnerability of populations of developing regions.

¶The purpose of the VSL is to monetize death costs by taking people’s willingness to pay to reduce the risk of death. This follows the valuation method used by ref. 32.

#For a detailed description of each impact module, see https://www.fund-model.org.

∥We use the version of FUND implemented with Mimi. Mimi is a Julia package that provides a component model for integrated assessment models. It is being developed by a team led by University of California, Berkeley’s David Anthoff, in connection with Resources for the Future’s Social Cost of Carbon Initiative.

††We thus use secondary data on bilateral migration flows. These datasets have the benefit of exhaustivity, crucial for our purpose. Existing primary datasets on international bilateral flows, often based on data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (37), omit many migration corridors, in particular for South–South migration.

‡‡In this part of the literature, migration models feature such a constraint: Income per capita at origin and that at destination have effects of the same magnitude and opposite signs on migration flows. For instance, ref. 17 calibrates this elasticity following ref. 38, which uses data on migration to Spain for this purpose. In our estimation, we allow for coefficients on income at origin and destination to be different and find in our global dataset that origin income actually has a positive, albeit smaller effect on migration than destination income. Thus, our estimation suggests that resources at origin are important for international migration to take place. On the contrary, refs. 17 and 38 model migration costs, but no resource constraint to migration.

§§This project has been conducted by one of the present authors (H.B.), as well as Jesús Crespo Cuaresma, Matthew Gidden, and Raya Muttarak. Scenarios data is accessible as indicated in Data Availability.

##The DEMIG project stands for Determinants of International Migration: A Theoretical and Empirical Assessment of Policy, Origin and Destination Effects. It was conducted at the University of Oxford between 2010 and 2015 and investigated “how policies of destination and origin states shape the volume, geographical orientation, composition, and timing of international migration” (p. 887 in ref. 50).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2007597117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

Code and data have been deposited in Figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13009988.v1 (51).

References

- 1.The Government Office , Foresight: Migration and Global Environmental Change: Final Project Report (The Government Office for Science, London, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desmet K., et al. , Evaluating the economic cost of coastal flooding. Am. Econ. J. Macroeconomics, in press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cattaneo C., et al. , Human migration in the era of climate change. Rev. Environ. Econ. Pol. 13, 189–206 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mastrorillo M., et al. , The influence of climate variability on internal migration flows in South Africa. Glob. Environ. Change 39, 155–169 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rigaud K. K., et al. , “Groundswell: Preparing for internal climate migration” (Report, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2018), pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLeman R., International migration and climate adaptation in an era of hardening borders. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 911–918 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nawrotzki R. J., Riosmena F., Hunter L. M., Runfola D. M., Amplification or suppression: Social networks and the climate change—Migration association in rural Mexico. Glob. Environ. Change 35, 463–474 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grecequet M., DeWaard J., Hellmann J. J., Abel G. J., Climate vulnerability and human migration in global perspective. Sustainability 9, 720 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrasco-Escobar G., Schwarz L., Miranda J. J., Benmarhnia T., Revealing the air pollution burden associated with internal migration in Peru. Sci. Rep. 10, 7147 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cattaneo C., Peri G., The migration response to increasing temperatures. J. Dev. Econ. 122, 127–146 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peri G., Sasahara A., “The impact of global warming on rural-Urban migrations: Evidence from global big data” (Rep. 25728, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2019).

- 12.Gemenne F., Climate-induced population displacements in a 4c+ world. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 369, 182–195 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolstad C., et al. , “Social, economic and ethical concepts and methods” in Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Edenhofer O., et al., Eds. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, 2014), pp. 207–282. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine , Valuing Climate Damages: Updating Estimation of the Social Cost of Carbon Dioxide (The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2017), pp. 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anthoff D., Tol R. S. J., The uncertainty about the social cost of carbon: A decomposition analysis using FUND. Clim. Change 117, 515–530 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desmet K., Rossi-Hansberg E., On the spatial economic impact of global warming. J. Urban Econ. 88, 16–37 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burzynski M., Deuster C., Docquier F., de Melo J., Climate change, inequality and human migration. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02394518 (4 December 2019).

- 18.Abel G. J., Brottrager M., Cuaresma J. C., Muttarak R., Climate, conflict and forced migration. Glob Environ. Change 54, 239–249 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borjas G. J., The economic benefits from immigration. J. Econ. Perspect. 9, 3–22 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ortega F., Peri G., Openness and income: The roles of trade and migration. J. Int. Econ. 92, 231–251 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams R. H., Evaluating the economic impact of international remittances on developing countries using household surveys: A literature review. J. Dev. Stud. 47, 809–828 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang D., International migration, remittances and household investment: Evidence from Philippine migrants’ exchange rate shocks. Econ. J. 118, 591–630 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duro J. A., Padilla E., International inequalities in per capita CO2 emissions: A decomposition methodology. Energy Econ. 28, 170–187 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Büchs M., Schnepf S. V., Who emits most? Associations between socio-economic factors and Uk households’ home energy, transport, indirect and total CO2 emissions. Ecol. Econ. 90, 114–123 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen J. E., Roig M., Reuman D. C., GoGwilt C., International migration beyond gravity: A statistical model for use in population projections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 15269–15274 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim K., Cohen J. E., Determinants of international migration flows to and from industrialized countries: A panel data approach beyond gravity. Int. Migrat. Rev. 44, 899–932 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fokkema T., Cela E., Ambrosetti E., Giving from the heart or from the ego? Motives behind remittances of the second generation in Europe. Int. Migrat. Rev. 47, 539–572 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ortega F., Peri G., “The causes and effects of international migrations: Evidence from OECD countries 1980-2005” (Rep. 14833, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones-Lee M. W., Paternalistic altruism and the value of statistical life. Econ. J. 102, 80–90 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sunstein C. R., Lives, life-years, and willingness to pay. Columbia Law Rev. 104, 205 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johansson-Stenman O., Martinsson P., Are some lives more valuable? An ethical preferences approach. J. Health Econ. 27, 739–752 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nordhaus W. D., Boyer J., Warming the World: Economic Models of Global Warming (MIT Press, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anthoff D., Emmerling J., Inequality and the social cost of carbon. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 6, 243–273 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azose J. J., Raftery A. E., Estimation of emigration, return migration, and transit migration between all pairs of countries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 116–122 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abel G. J., Cohen J. E., Bilateral international migration flow estimates for 200 countries. Sci. Data 6, 82 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abel G. J., Estimates of global bilateral migration flows by gender between 1960 and 2015. Int. Migrat. Rev. 52, 809–852 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cai R., Feng S., Oppenheimer M., Climate variability and international migration: The importance of the agricultural linkage. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 79, 135–151 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertoli S., Fernander-Huertas-Moraga J., Multilateral resistance to migration. J. Dev. Econ. 102, 79–100 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 39.The World Bank, Remittance Prices Worldwide . http://remittanceprices.worldbank.org. Accessed 1 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lutz W., et al. , Demographic Scenarios for the EU: Migration, Population and Education (Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Neill B. C., et al. , The roads ahead: Narratives for shared socioeconomic pathways describing world futures in the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 169–180 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 42.KC S., Lutz W., The human core of the shared socioeconomic pathways: Population scenarios by age, sex and level of education for all countries to 2100. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 181–192 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lutz W., et al. , Demographic and Human Capital Scenarios for the 21st Century: 2018 Assessment for 201 Countries (Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 44.KC S., “Updated demographic SSP4 and SSP5 scenarios complementing the SSP1-3 scenarios published in 2018” (WP-20-016, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, Austria, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Neill B. C., et al. , The scenario model intercomparison project (scenariomip) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gidden M. J., et al. , Global emissions pathways under different socioeconomic scenarios for use in CMIP6: A dataset of harmonized emissions trajectories through the end of the century. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 1443–1475 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 47.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Dynamics, World Population Prospects 2019, Online Edition. Rev. 1 . https://population.un.org/wpp/. Accessed July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 48.The World Bank, World Development Indicators . https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators. Accessed 1 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anthoff D., Tol R., Data from “FUND - Climate framework for uncertainty, negotiation and distribution, Version v3.12.0.” GitHub. https://github.com/fund-model/MimiFUND.jl. Accessed 1 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haas H. D., et al. , International migration: Trends, determinants, and policy effects. Popul. Dev. Rev. 45, 885–922 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benveniste H., Oppenheimer M., Fleurbaey M., Effect of Border Policy on Exposure and Vulnerability to Climate Change. Figshare. Software. 10.6084/m9.figshare.13009988.v1. Deposited 25 September 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Code and data have been deposited in Figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13009988.v1 (51).