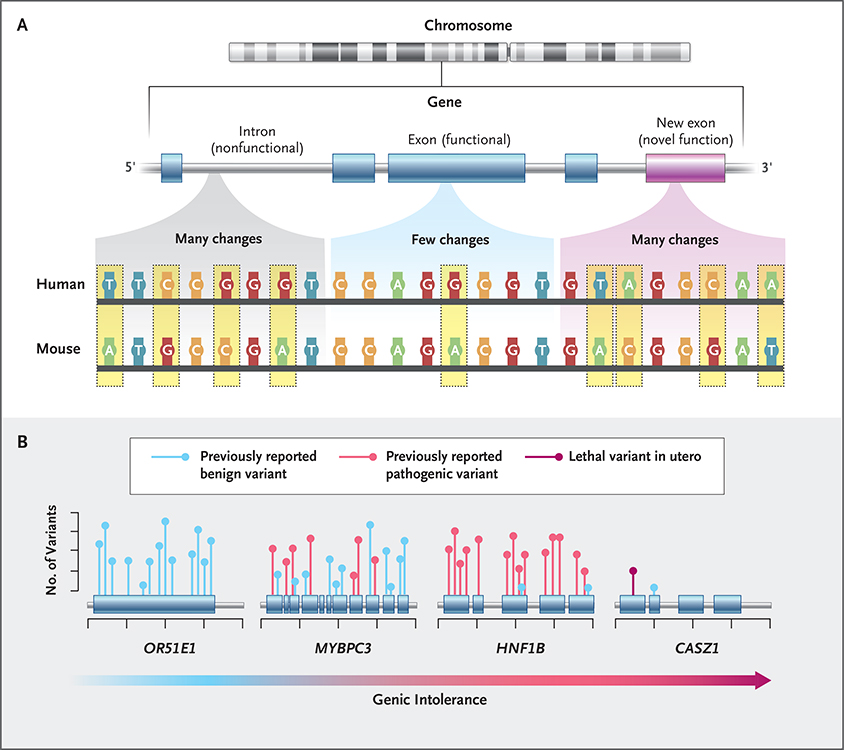

Figure 1. Intolerance to Genetic Variation.

Regions of the human genome that are under the strongest natural selection are the most likely to cause disease when they are variant. Until 2013, the primary approach that was used to identify such regions relied on the genetic similarities of different species.25 Genomic regions under selection show fewer DNA changes (e.g., nucleotide substitutions, deletions, or insertions) across species and are likely to be functionally important (Panel A). Pathogenic variants that cause human diseases have long been shown to fall preferentially within these “constrained” regions. Although this approach is useful, it cannot identify genomic regions of particular importance in humans, as might happen because of the evolution of a novel function. In 2013, a new framework was developed to address this limitation: variation, solely within the human population, was used to identify genes with less functional variation than expected according to genomewide averages. Genes with a depletion of human variation are termed “intolerant”26 and reflect parts of the genome under strong selection specifically in humans. Since the introduction of intolerance scoring, there have been a number of important elaborations focused on regions of genes, specific types of variants, and regulatory regions.27‑30 Intolerance scores have now been shown to provide independent information about where in the human genome pathogenic variants are found (Panel B).24,29,31‑34 For example, the gene encoding olfactory receptor 51E1 (OR51E1) is tolerant to variation and does not cause disease, whereas MYBPC3 and HNF1B are intolerant and are known to cause cardiac and kidney disease, respectively. CASZ1 is highly intolerant to variation in the healthy population, but no pathogenic variants have been reported in the literature regarding postnatal disease, which indicates that it may result in lethality when variant in utero.