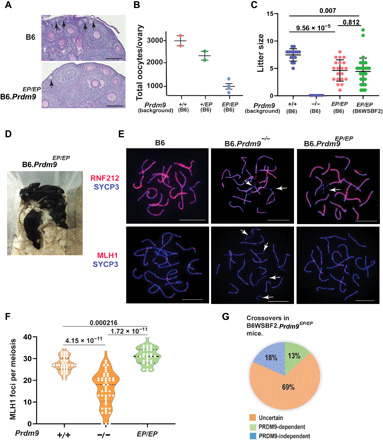

Fig. 2. Females homozygous for Prdm9EP are fertile.

(A) Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)–stained sections from 3-week postpartum ovaries in wild-type and Prdm9EP/EP mice in the B6 genetic background. Arrows show primary follicles. Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Oocytes per ovary in wild-type, heterozygous, and Prdm9EP/EP females (error bars, SEM). P values were not calculated as N = 2 is not sufficient for reaching statistical significance. (C) Litter sizes in wild-type, Prdm9−/−, and Prdm9EP/EP female mice (error bars, SEM). P values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. (D) Pups produced by Prdm9EP/EP female mice. (E) Coimmunolabeling detection of RNF212 foci (red, top row), MLH1 (red, bottom row), and SYCP3 (blue) in pachytene oocyte chromatin spreads in wild-type and mutant females. White arrows highlight unsynapsed regions of chromosomes. Scale bars, 10 μm. (F) Violin plot with dots showing numbers of MLH1 foci per meiotic oocyte (error bars, SEM), in wild-type, Prdm9−/−, and Prdm9EP/EP mice. P values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. (G) Diagram showing proportions of PRDM9-dependent and PRDM9-independent crossovers in progeny of B6WSBF2.Prdm9EP/EP females (n = 94). Photo credit: Natalie R. Powers and Tanmoy Bhattacharyya, The Jackson Laboratory.