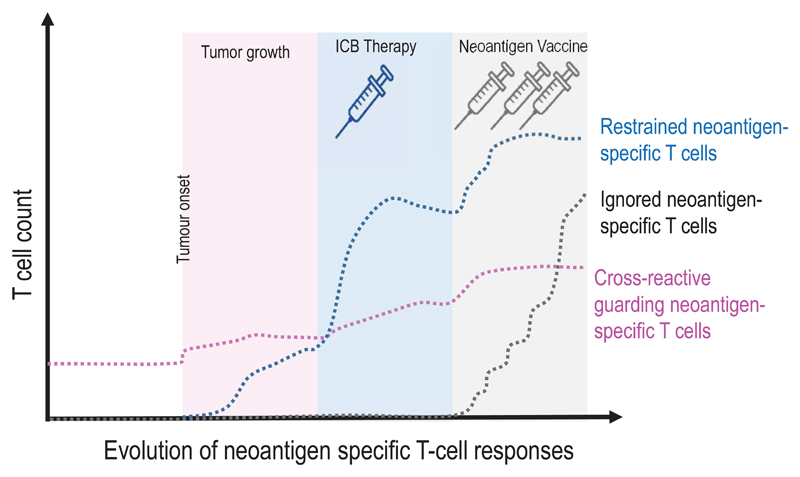

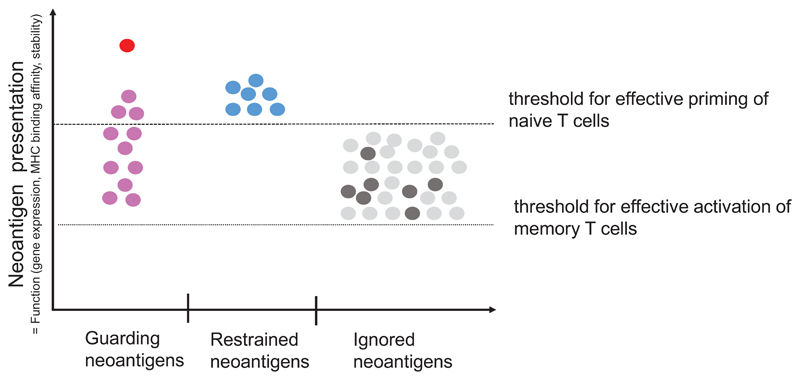

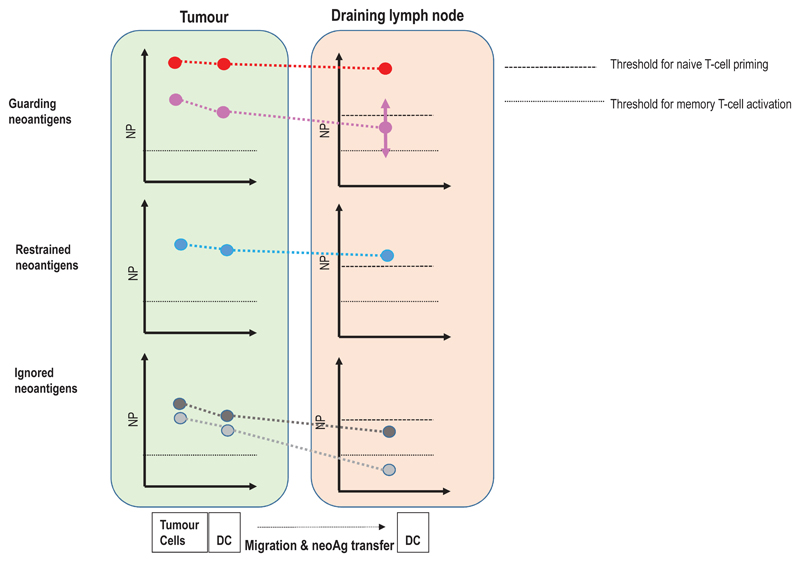

Figure 5. A context based classification of neoantigens.

(a) The formation and evolution of neoantigen-specific T-cell responses depends on the clinical context. While ICB therapy boosts pre-existing T-cell responses, neoantigen cancer vaccines induce de novo responses or amplify preformed ones. (b) The robustness and level of a neoantigen presentation on LN-resident DCs defines the efficiency of cognate priming of T cells, while presentation on tumour-resident APCs and tumour cells activates primed cells at the tumour site. Neoantigen presentation is a function of expression level of the mutated protein, the binding ability of the mutated peptide to MHC and stability of the respective peptide/MHC complex. Memory T cell activation can be achieved with neoantigen presentation levels 50 fold lower than those required for priming of naive T cells. Dark red: supreme neoantigen; pink cross-reactive guarding neoantigen (c) Neoantigen-specific T cell responses are driven by the presentation of neoepitopes on tumour cells, on tumour-infiltrating APCs, and on DCs in the draining lymph node. Priming of naïve T cells in the lymph node requires substantially higher neoantigen presentation than is required for stimulation of memory T cells. Guarding neoantigens are either highly expressed with superior binding and stability of the respective neoepitope/MHC complex (red) or exploit cross-reactivity to heterologously primed memory T cells (purple). Restrained neoantigens exhibit robust expression and strong MHC binding affinity/stability and are able to prime and expand naive neoantigen-specific T cells in the lymph node. Ignored neoantigens require a vaccine to generate neoantigen presentation levels in the LN that allow priming. As long as neoantigen presentation is moderate (e.g., low expression/high affinity MHC binding (dark gray) or high expression/low MHC binding (light gray), T cells can be activated for effector functions in the tumour. NP: level of neoepitope presentation, LN: lymph node, APC: antigen-presenting cell, ICB: immune checkpoint blockade